View sample criminal law research paper on sentencing guidelines. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

‘‘Sentencing guidelines’’ are rules or recommendations created by judges or an expert administrative agency, usually called a ‘‘sentencing commission,’’ which are intended to influence, channel, or even dictate the punishment decisions made by trial courts in individual cases. Since the early 1970s, commission-based guideline structures have emerged as the principal alternative to traditional practices of ‘‘indeterminate sentencing,’’ under which judges and parole boards hold unguided and unreviewable discretion within broad ranges of statutorily authorized penalties. Sentencing guidelines in operation have varied widely in their form, content, legal authority, and even in their nomenclature. (Not all guidelines are called guidelines.) It is thus treacherous to assume that ‘‘all guidelines are created equal.’’

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Origins of Sentencing Commissions and Guidelines

The idea of a ‘‘commission on sentencing’’ can be traced to Marvin Frankel’s influential writings of the early 1970s, most notably his 1973 book Criminal Sentences: Law Without Order. Frankel wanted to replace what he saw as the ‘‘lawless’’ processes of indeterminate sentencing with an alternative model that would promote legal regularity. His chosen vehicles were chiefly procedural innovations, and it is possible to identify three fundamental procedural goals in Frankel’s plan: (1) The creation of a permanent, expert commission on sentencing in every jurisdiction, with both research and rulemaking capacities; (2) the articulation of broad policies and more specific regulations (later called guidelines) by legislatures and sentencing commissions, to have binding legal authority on case-by-case sentencing decisions made by trial judges; and (3) institution of meaningful appellate review of the appropriateness of individual sentences, so that a jurisprudence of sentencing could develop through the accumulation of case decisions.

Along with these procedural elements, Frankel advocated for two major substantive goals: (1) Greater uniformity in punishments imposed upon similarly situated offenders, with a concomitant reduction in inexplicable disparities, including racial disparities in punishment and widely varying sentences based simply on the predilections of individual judges; and (2) a substantial reduction in the overall severity of punishments as imposed by courts throughout the United States, including a general shortening of terms of incarceration, and the expanded use of intermediate punishments.

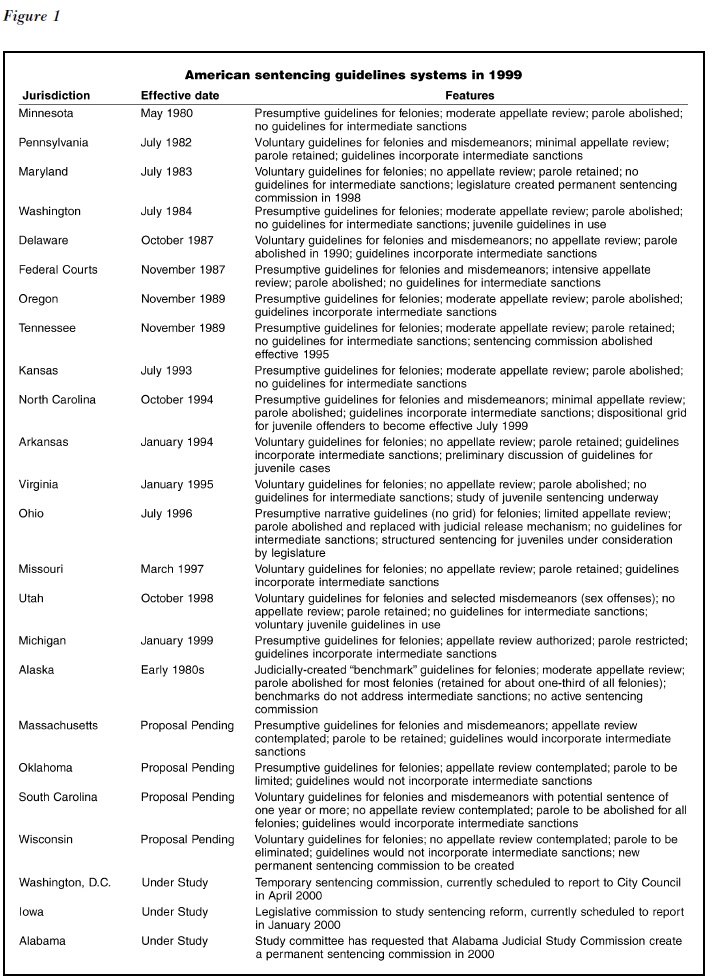

Frankel’s suggestions that U.S. jurisdictions should create permanent sentencing commissions, which in turn should author sentencing guidelines, have been enormously productive of institutional changes. In the early 1970s, commissions and guidelines were wholly new ideas, and existed nowhere. By midyear 1999, as summarized in Figure 1, sixteen American jurisdictions were operating with some form of sentencing guidelines (including fifteen states and the federal system). In four additional states, fully developed guideline proposals are under consideration by the state legislatures, and at least three more jurisdictions were in the early stages of deliberations that may eventually lead to commission-based sentencing reform. In nearly thirty years since Frankel’s seminal writings, this is a remarkable record indeed, unrivaled by nearly any other work of criminal-law-related scholarship over the same period.

Design Features of Guideline Structures

Up-and-running guideline systems have differed substantially from one another, and not all guidelines systems have conformed closely to Marvin Frankel’s ambitions. As of 1999, we can identify a menu of choices faced by policymakers who undertake to create a new sentencing guideline structure, or who are interested in amending an existing structure. We will begin here by identifying a number of the most important ‘‘design features’’ of existing guideline systems. These are also salient attributes for assessing operational distinctions among guideline jurisdictions.

Guideline Grids

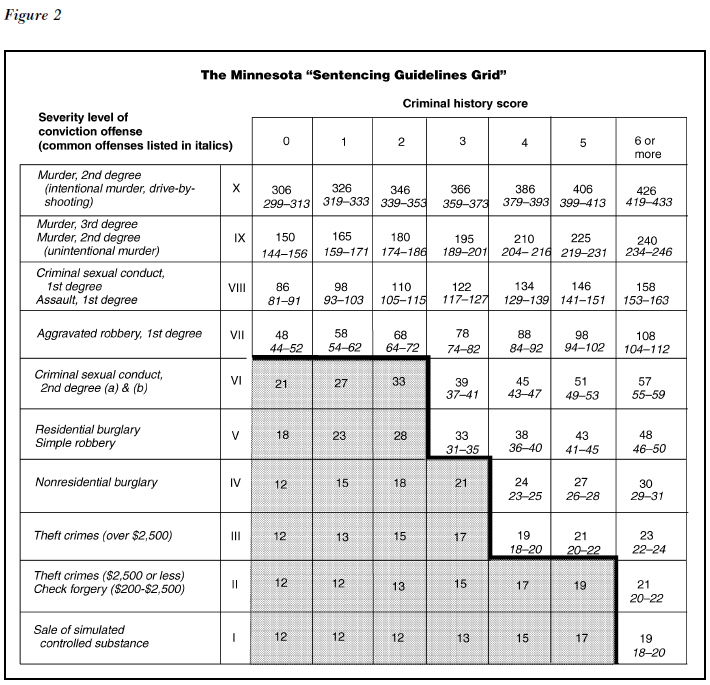

Most sentencing guideline systems in America in the late twentieth century used the format of a two-dimensional ‘‘grid’’ or ‘‘matrix.’’ Figure 2 provides an illustration of the popular grid approach, taken from the Minnesota Guidelines (see Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, 1997, p. 43). Along one axis of the grid, such guidelines rank offense severity on a hierarchical scale. On the other axis, a similar scale reflects the seriousness of the offender’s prior criminal history. The guideline sentence in a particular case is derived by moving across the row designated for the offense to be punished, and down the column that corresponds to the offender’s past record. Thus, for example, the guideline sentence under Minnesota’s current grid for a conviction of residential burglary (‘‘severity level V’’) by someone with a ‘‘criminal history score’’ of 4 (calculated by the number of prior felony sentences and their severity levels) is thirtysix to forty months of incarceration in a state prison.

The tightness or looseness of such ‘‘sentencing ranges’’ has differed greatly among American guideline jurisdictions, from a bandwidth of several months to as much as several years. For instance, the Pennsylvania guidelines in the early 1990s recommended penalty ranges as expansive as three to ten years for third degree murder and twenty-seven months to five years for rape and robbery with serious injury. (See Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing, Sentencing Guideline Implementation Manual, 3d ed., 9 August 1991, p. 12(a).) Thus, when comparing different systems, we may speak in terms of fine-toothed or broad-gauged sentencing guidelines, depending on the specificity with which the sentencing commission has articulated its punishment ranges.

Most guideline grids differentiate explicitly between sentences to incarceration and to nonprison sanctions. In Figure 2, the heavy black line that runs diagonally though the Minnesota grid is called the ‘‘in-out’’ line. For cases above the in-out line, the ‘‘presumptive’’ sentences in Minnesota are all prison terms. Offenders who fall within the guideline cells below the in-out line are subject to a ‘‘presumptive stayed sentence,’’ which can include probation or any available intermediate sanction (although, in the Minnesota system, a ‘‘stayed’’ sentence may also include up to a year in jail at the discretion of the sentencing judge). For such cases, the number appearing in the grid cell is the presumptive duration of a stayed sentence. The Minnesota guidelines, it should be noted, do nothing to communicate to the judge which among the array of nonprison sanctions are appropriate in individual cases. Thus, no guidance is given to courts concerning the selection among such options as regular probation, intensive probation, in-patient or out-patient treatment programs, halfway houses, home confinement, community service, fines, victim restitution, and so forth. Such choices below the in-out line remain discretionary with the sentencing judge in Minnesota’s structure.

Guidelines for Intermediate Punishments

Some sentencing guidelines do provide at least limited direction to courts concerning the selection among intermediate punishment options. This is still an experimental undertaking, however, and one that has been attempted with ambition in only two or three states. The current North Carolina ‘‘Felony Punishment Chart,’’ reproduced as Figure 3, illustrates one promising innovation in operation since 1994. For the most serious cases (such as all of those in offense classes A through D on the chart), North Carolina’s guidelines prescribe an ‘‘active punishment,’’ designated by the letter ‘‘A’’ in each guideline cell. This is defined as a state prison sentence. For less serious cases, other cells within the guidelines authorize ‘‘intermediate punishments,’’ denoted by the letter ‘‘I,’’ and defined to include split sentences (prison then probation), boot camp, residential programs, electronic monitoring, intensive probation, and day reporting centers. Finally, and for those offenses and offenders lowest on North Carolina’s severity scale, ‘‘community punishments’’ become available, indicated by the letter ‘‘C,’’ which include supervised or unsupervised probation, outpatient drug or alcohol treatment, community service, referral to the federal TASC (drug treatment) program, restitution, and fines (North Carolina Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission, Structured Sentencing for Felonies: Training and Reference Manual, 1995, pp. 21–22). Many of the cells on the North Carolina chart allow the judge to select from more than one category of sentence disposition—such as the first four cells at Offense Class G—which indicate the propriety of either an ‘‘active’’ or ‘‘intermediate’’ punishment, in the court’s discretion. (Examples of offenses classified at level G are domestic abuse, burglary in the second degree, causing death by impaired driving, and various drug trafficking crimes; p. 51).

The North Carolina grid is an advance over the Minnesota system in that the guidelines direct judges to relevant clusters of punishment options, rather than committing the choice among sanctions to free-form judicial discretion. Further, instead of utilizing a firm and unambiguous in-out line, North Carolina has substituted a diagonal swath of cells in which judges are free to select interchangeably among ‘‘active’’ and ‘‘intermediate’’ punishments (see the cells marked ‘‘I/A’’ in Figure 3). This follows a suggestion made by Norval Morris and Michael Tonry in their 1990 work Between Prison and Probation, that the in-out line should be a ‘‘blurred’’ line instead of a hard-and-fast demarcation—in recognition of a policy judgment that intermediate punishments should sometimes be viewed as the functional equivalents of incarceration, and should be available for offenders who otherwise would be prison-bound (pp. 29–30).

At least two other states employ scaled clusters of punishment options within their guidelines. The Pennsylvania sentencing matrix, as revised in 1997, specifically directs courts toward ‘‘state or county incarceration,’’ ‘‘boot camp,’’ ‘‘restrictive intermediate punishments,’’ and ‘‘restorative sanctions,’’ depending upon the position of individual cases within five zones of the guideline matrix (Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing, Sentencing Guidelines Implementation Manual, 5th ed. 13 June 1997, p. 33). Delaware’s sentencing guidelines, although not expressed in a grid format (see below), designate five graduated levels of recommended sanctions to sentencing judges: ‘‘full incarceration,’’ ‘‘quasi-incarceration,’’ ‘‘intensive supervision,’’ ‘‘field supervision,’’ and ‘‘administrative supervision’’ (Delaware Sentencing Accountability Commission, 1997, pp. 2–3).

The ‘‘Grading’’ Distinctions in Guidelines

Another central design feature of a sentencing guideline system is the number of severity (or grading) distinctions that the system attempts to capture within the guidelines themselves—as opposed to allowing trial judges discretion to sort among shadings of offense gravity. As Albert Alschuler noted in a classic 1978 article, there is something ridiculous about having 132 grades of robbery—but how far should guidelines go in such a direction? The number of formal classifications written into guideline grids has differed greatly across jurisdictions, but most guidelines have been modest in their attempts at grading precision. The grids in state jurisdictions have generally incorporated nine to fifteen levels of offense severity, and four to nine categories for offenders’ prior records. The Minnesota grid in Figure 2 is representative: Its ten-by-seven format contains a total of seventy guideline ‘‘cells’’ or ‘‘boxes.’’ The North Carolina chart in Figure 3, also representative, features a total of fifty-four cells.

The current federal sentencing guidelines system, inaugurated in 1987, opted for a much more intricate matrix than those used by the states, reflecting a philosophy that the U.S. Sentencing Commission can and should make precise distinctions among cases in advance of adjudication in the courts. The federal grid incorporates forty-three levels of crime seriousness and six categories for prior criminal history, yielding a total of 258 guideline cells. If anything, however, the visual complexity of the federal grid understates the degree to which the federal system attempts to draw fine distinctions among specific cases. Unlike all state guideline systems, offense severity under federal law is not fixed by the crime(s) of conviction. The conviction offense is merely one factor among many fed into a multistep calculation, including ‘‘relevant conduct’’ (other related crimes the defendant probably committed, but for which convictions were not obtained), a point-scale scoring of the ‘‘base offense level’’ (which can go up or down depending on such things as the weight of the drugs involved in a narcotics offense or the amount of money lost in a fraud case), and further point ‘‘adjustments’’ for surrounding circumstances (for example, two points off for ‘‘acceptance of responsibility,’’ or two points added for ‘‘more than minimal planning’’). In these and other respects (mentioned below), the federal guidelines are the most ‘‘fine-toothed’’ and rigid of any guideline system now in operation across the country. For all of its size and complexity, however, the federal grid does nothing to assist sentencing judges in the selection among intermediate punishments.

Narrative Guidelines

In two U.S. jurisdictions (Delaware and Ohio), the sentencing commissions have eschewed the grid apparatus and have elected to communicate their guidelines in narrative form—expressing punishments though verbal exposition rather than a numerical table. For example, in Delaware, the ‘‘presumptive’’ sentence for first-degree burglary by a first-time offender is written out in a ‘‘Truth in Sentencing Benchbook’’ as twenty-four to forty-eight months at ‘‘Level V.’’ (In the Delaware guidelines, Level V is a prison sentence.) Longer presumptive prison terms are indicated for defendants with prior records. For instance, a first-degree burglar with ‘‘two or more prior violent felonies’’ receives a presumptive sentence of 60 to 120 months (or five to ten years) in the Delaware Benchbook (Delaware Sentencing Accountability Commission, Truth in Sentencing Benchbook, March 1997, p. 23). Delaware’s guidelines look more like a series of statutes or textual regulations than most other guidelines, and rely less on visual aids. To date, however, the distinction between narrative guidelines and those distilled into grid form has been largely stylistic. With small ingenuity, the current narrative guidelines in use in Delaware or Ohio could be summarized pictorially in a grid or matrix. Conversely, all ‘‘grid jurisdictions’’ supplement their guideline matrices with narrative provisions, which can be quite voluminous, addressing such topics as the purposes of punishment, the permissible grounds for departure for the guidelines, the treatment of multiple convictions, and the computation of criminal history scores. Overall, the design choice between grid and non-grid formats has mattered much less than substantive choices about sentence severity, guideline specificity, intermediate punishments, and other central policy issues.

The Legal Force of Guidelines

Perhaps the most important design feature of existing guideline systems has been the degree of binding legal authority assigned to the sentencing ranges laid out in the guidelines. On one extreme, seven states presently operate with guidelines that are ‘‘voluntary,’’ or merely ‘‘advisory,’’ to the sentencing judge. In such systems, the court is free to consult or disregard the relevant guideline, and is permitted to impose any penalty authorized by the statute(s) of conviction. For example, a given case may be subject to a guideline range of forty-two to fifty months, yet otherwise be subject to a statutory maximum sentence of fifteen years (180 months). The full incarceration range available in the criminal code could be as wide as zero to 180 months—with the terms and conditions of any nonincarcerative penalty often left to the discretion of the judge, as well. In voluntary guideline systems, the specific guideline range of forty-two to fifty months is merely a recommendation within the much broader range of statutory options freely available to the judge.

There is one variation on this voluntaryguideline approach that exerts light pressure upon trial courts to stay within the guideline ranges: A number of states with voluntary guidelines require sentencing courts to produce a written explanation whenever they opt not to employ the suggested guideline penalty. This supplies at least a mild incentive for courts to abide by guideline provisions, since no similar burden of explanation attends a guideline-compliant decision. The required explanations also provide data to the sentencing commission, allowing the commission to identify frequently cited reasons for judicial noncompliance.

In a bare majority of current guideline structures (nine of sixteen jurisdictions in 1999, including the federal system), the stated guideline range carries a degree of enforceable legal authority. Under the Minnesota scheme, which has been emulated in a number of other states (including Washington, Oregon, Kansas, and the pending proposal in Massachusetts), trial courts are instructed that they must use the presumptive sentences in the guideline grid in ‘‘ordinary’’ cases—which in theory include the majority of all sentencing decisions. However, the trial judge retains discretion to ‘‘depart’’ from the guidelines in a case the judge finds to be atypical in some important respect. In the Minnesota model, the formal legal standard for a guideline departure is that the sentencing judge must find, and set forth on the record, ‘‘substantial and compelling reasons’’ why the presumptive guideline sentence would be too high or too low in a given case. Provided an adequate justification exists, the trial court is potentially freed from the guidelines and may choose a penalty from the broader range of options authorized by the statute(s) of conviction. A judge’s departure sentence, however, may be appealed by the defendant (where there has been an ‘‘aggravated’’ departure) or by the government (following a ‘‘mitigated’’ departure). Ultimately, the appellate courts review whether the trial court has given sufficient reasons for a departure, and whether the degree of departure is consistent with those reasons. In almost all jurisdictions with legally enforceable guidelines, however, a sentence that conforms to the guidelines requires no explanation by the sentencing court and may not be appealed. Thus, in such systems, trial judges have a dual procedural incentive to honor the guidelines: when they do so, they need not justify their action with a statement of reasons, and there is no prospect of reversal by a higher court.

Two jurisdictions have built sentencing structures in which the guidelines are more tightly legally confining upon trial judges than in the Minnesota model. The federal guideline system bears surface similarity to the Minnesota approach, except that the ‘‘departure power’’ retained by trial courts is more strictly limited under federal law than in Minnesota and most other states. By federal statute, district court judges may impose a departure sentence only when ‘‘there exists an aggravating or mitigating circumstance of a kind, or to a degree, not adequately taken into consideration by the Sentencing Commission in formulating the guidelines that should result in a sentence different from that described’’ (emphasis added). The same statute further provides that, ‘‘In determining whether a circumstance was adequately taken into consideration, the court shall consider only the sentencing guidelines, policy statements, and official commentary of the Sentencing Commission’’ (18 U.S.C. § 3553(b)). As interpreted by the federal courts of appeals, this departure standard has been used regularly and often to reverse district court sentences outside the guidelines. A 1997 study found that the chances of a trial court’s sentence being reversed on appeal were ten times greater in the federal system than in Minnesota, and fifty times greater than in Pennsylvania (Reitz, 1997). Thus, the federal guidelines are probably the most restrictive of judicial discretion of any yet created in the United States— because of their narrow ranges, the number of fine grading distinctions they draw among cases, and their unusually high degree of legal enforceability.

The only state guidelines to rival the federal system in legal authority are the North Carolina guidelines. Alone among guideline systems so far invented, there is no departure power in North Carolina. By statute, the trial court must impose a guideline sentence in every case. In effect, the guidelines have replaced the former maximum and minimum penalties that used to exist as a matter of statutory law.

Offsetting the forceful legal punch of the North Carolina guidelines, the sentencing ranges available to judges are generally broad in comparison with the federal system and the guidelines in many other states. A judge in North Carolina may select a sentence in the ‘‘presumptive range’’ as depicted in the ‘‘Felony Punishment Chart’’ (Figure 3), but the judge has unreviewable discretion to elect a sentence from the ‘‘aggravated’’ or ‘‘mitigated’’ ranges that are also set out on the chart. Thus, for example, in box E(I) on the North Carolina chart, the judge could impose an ‘‘active’’ (prison) sentence of any length between fifteen and thirty-one months, or the judge could substitute one or more ‘‘intermediate punishments.’’ No appellate court may second-guess the trial judge across this continuum of possibilities. Appellate review exists only for ‘‘unlawful’’ sentences that reach beyond the aggravated or mitigated ranges.

The North Carolina model is unique among existing guideline structures. In the run-of-themill cases, North Carolina trial judges have more discretion (because of the breadth of available sentencing ranges) than judges in other jurisdictions where guidelines are legally binding. However, the North Carolina law cuts off sentencing options at the extreme high and low ends that remain available to judges in other jurisdictions, at least in sufficiently unusual cases, through the vehicle of the departure power.

In summary, the degree of real authority exerted by a set of guidelines upon trial judges depends upon a combination of factors: whether the guidelines are characterized by the legislature as legally binding or as advisory to the courts; whether the stated sentencing ranges are fine-toothed or broad-gauged; how many grading distinctions are built into the guidelines; whether the ‘‘departure power’’ retained by judges is defined in a broad or stingy fashion—if it exists at all; and whether the appellate courts are vigilant or lax in their guideline-enforcement function. Even a quick review of established sentencing guideline structures reveals a full spectrum of possibilities on all of these dimensions: Some guidelines are wholly advisory, some exert an exceedingly light touch on judicial authority, some are legally enforceable yet flexible when a sentencing judge feels strongly about a case (and can provide a reasoned basis for the feeling), and some guidelines are tightly restrictive—even mandatory—in their effects on sentencing outcomes. As noted earlier, all guidelines are not created equal.

Guidelines and Parole Release

The workings of any set of sentencing guidelines are interrelated with the sentencing authority held by other institutional actors in the punishment system. The impact of sentencing guidelines on prison terms can be greatly affected by the presence or absence of a parole board with authority to set release dates for incarcerated offenders. Marvin Frankel argued in the early 1970s that parole release should be cut back once sentencing commissions had brought rational uniformity to the penalties imposed by judges, and Frankel joined other voices decrying the standardless, arbitrary, and unreviewable nature of parole board decision-making. Among guideline systems as of 2001, nine of sixteen legislatures have chosen to abolish parole release in conjunction with guideline reform—usually under the banner of ‘‘truth in sentencing.’’ (See Figure 1.) In such systems, the guideline sentence pronounced by the trial judge, allowing for good-time reductions by prison authorities, will bear close resemblance to the sentence actually served by the convicted offender.

The remaining seven guideline jurisdictions, however, have retained parole release discretion in some form. Thus, for example, in Pennsylvania, the guidelines for prison cases set forth minimum terms of incarceration. Under state law, the maximum must then be set equal to at least double the minimum. The Pennsylvania parole board enjoys authority to release prisoners who have served the minimum sentence, but the board may also in its discretion require the prisoner to serve out the full sentence (with adjustment for good time credits). On the other side of the scale, Congress’s Sentencing Reform Act (authorizing the federal guidelines) abolished parole release and limited the availability of good time to 15 percent of an offender’s pronounced sentence. Thus, in the federal system, incarcerated offenders serve a minimum of 85 percent of imposed penalties.

Facts Relevant to Sentencing

All guideline jurisdictions have found it necessary to create rules that identify the factual issues at sentencing that must be resolved under the guidelines, those that are potentially relevant to a sentencing decision, and those viewed as forbidden considerations that may not be taken into account by sentencing courts. One heated controversy, addressed differently across jurisdictions, is whether the guideline sentence should be based exclusively on crimes for which offenders have been convicted (‘‘conviction offenses’’), or whether a guideline sentence should also reflect additional alleged criminal conduct for which formal convictions have not been obtained (‘‘nonconviction offenses’’). Nonconviction offenses, as cataloged by Reitz in 1993, may include crimes for which charges were never brought, charges dismissed as part of a plea bargain, and even charges resulting in acquittals at trial. Sentencing based freely upon both conviction and nonconviction crimes is often called real-offense sentencing.

As noted earlier, the federal sentencing guidelines require trial judges to base guideline calculations upon conviction offenses and nonconviction offenses in some circumstances. Under the federal guidelines’ ‘‘relevant conduct’’ provision, if a nonconviction crime is related to the offense of conviction (that is, if it is similar in kind or arose from the same episode), and if the defendant’s guilt has been established by a preponderance of the evidence during sentencing proceedings, then the trial judge must compute the guideline punishment as though the defendant had been convicted of the nonconviction charge. Real-offense sentencing in such cases is mandatory in the federal system. To give one striking example, in United States v. Juarez-Ortega, 866 F.2d 747 (5th Cir. 1989), a defendant convicted at a jury trial of a drug charge but acquitted of a related gun charge was sentenced as though convictions had been returned on both counts. The trial judge found by a preponderance of the evidence that—despite the jury’s acquittal—the defendant was guilty of the nonconviction gun offense.

State guideline systems have all gone in a different direction than the federal system on this issue. Instead of mandating real-offense sentencing, the consideration of nonconviction crimes is usually restricted to departure cases in the states or, in a few jurisdictions, is prohibited outright. All guideline grids set out presumptive sentences based on conviction offenses and prior convictions; no state follows the federal example of adding or substituting nonconviction offenses for purposes of the initial guideline calculation. Thus, presumptive sentences, intended to govern all typical cases, are oriented solely toward conviction crimes. In some guideline states, including all voluntary-guideline jurisdictions, a trial court may deviate from the guidelines in the belief that the defendant’s ‘‘real’’ offenses were more numerous or more serious than those reflected in the verdict or guilty plea. Unlike the federal system, however, such consideration of nonconviction crimes is discretionary with the court rather than mandatory, and is limited to departure cases. In at least three states, even departure sentences based on nonconviction conduct are legally forbidden. Thus, for example, a sentence such as the one imposed in the JuarezOrtega case above would be struck down on appeal in Minnesota, Washington, and North Carolina.

Another difficult issue of fact-finding at sentencing for guideline designers has been the degree to which trial judges should be permitted to consider the personal characteristics of offenders as mitigating factors when imposing sentence. For example: Is the defendant a single parent with young children at home? Is the defendant addicted to drugs but a good candidate for drug treatment? Has the defendant struggled to overcome conditions of economic, social, or educational deprivation prior to the offense? Was the defendant’s criminal behavior explicable in part by youth, inexperience, or an unformed ability to resist peer pressure? Most guideline states, once again including all jurisdictions with voluntary guidelines, allow trial courts latitude to sentence outside of the guideline ranges based on the judge’s assessment of such offender characteristics. Some states, fearing that race or class disparities might be exacerbated by unguided consideration of such factors, have placed limits on the list of eligible concerns. For example, in Minnesota, judges are not permitted to depart from the guidelines because of a defendant’s employment history, family ties, or stature in the community. (However, such factors may indirectly affect the sentence, since judges are permitted to base departures on the offender’s particular ‘‘amenability’’ to probation (Frase, 1997).)

Once again, the federal system is an outlier among guideline jurisdictions in its sweeping proscriptions of the consideration of offender characteristics. All of the personal attributes mentioned in the preceding paragraph are treated as forbidden or discouraged grounds for departure in federal law. If a federal judge wishes to tailor a sentence to a defendant’s old age and infirmity, youth and inexperience, family obligations, or amenability to rehabilitation, the case law has required that the trial judge may do so only in truly ‘‘extraordinary’’ cases—and the federal courts of appeals have been vigilant in reversing lower court sentences deemed too easily responsive to sympathetic offender attributes (on the ground that, however sympathetic, the attributes are not sufficiently extraordinary). In contrast to the experience of state judges under state guidelines, U.S. District Court judges complain loudly that the federal guidelines have excised the human component of sentencing decisions.

Evaluations of Guidelines in Operation

So far we have been concerned with the structural and procedural architecture of sentencing guideline systems. A different set of issues arises when we ask how well or poorly the new guidelines have performed in operation. While the guideline evaluation literature is shockingly thin, especially that focused on the states as opposed to the federal system, twenty years of experience under guidelines permits a number of observations about their successes and failures.

Uniformity in Sentencing

First, it is probably fair to say that ‘‘uniformity in sentencing’’ has proven to be a more elusive commodity than sentencing reformers foresaw in the 1970s. For one thing, the past few decades have not yielded a consensus on what counts as uniformity. Nearly all guideline systems report that, in the great majority of cases, trial judges follow the applicable guidelines when imposing sentences. Surprisingly, high rates of guideline compliance are reported by a number of commissions with voluntary guidelines (including Delaware, Pennsylvania, and Virginia), as well as in jurisdictions with legally enforceable guidelines. Many people accept such reports as evidence of marginal improvements in sentencing uniformity when comparing guidelines with traditional indeterminate sentencing systems.

Critics, of the federal guidelines in particular, argue that high rates of guideline compliance show nothing more than false uniformity in sentencing. Such claims, in part, go to the very definition of uniformity: If one believes that federal guidelines mandate lock-step punishments that exclude consideration of important offender characteristics, then the federal guidelines will appear to demand rigidly disparate sentences (e.g., the person who committed crime x for reasons of economic deprivation gets the same sentence as the person who committed crime x out of pure avarice). On the other hand, if one believes that most personal characteristics of defendants should be removed from the sentencing calculus, and that punishment should be matched closely to criminal conduct, then current federal sentences tend to look both more appropriate and more uniform in application. Uniformity (as against what baseline) tends to be in the eye of the beholder.

Aside from such fundamental disagreements, which do not promise to dissipate any time soon, evaluators of existing guideline systems have discovered, or strongly suspected, that the plea bargaining process can work to undermine the goal of sentencing uniformity. A sophisticated study by Nagel and Schulhofer in 1992 of the federal guidelines in three cities found that the parties were ‘‘circumventing’’ the guidelines as often as 35 percent of the time through plea negotiations. Richard Frase’s 1993 assessment concluded that plea bargaining remained a major force in sentencing outcomes after Minnesota’s guidelines were implemented, as well— although perhaps no more so than before the guidelines. Again, there are different ways to assess the meager evidence in hand: It seems likely that plea negotiations are channeled by the parties’ expectations of what the ultimate sentences in their cases would be under guidelines, and that negotiated resolutions thus treat the guidelines as a meaningful point of departure. However, the empirical evidence is far too slight to permit anyone to prove it, so the controversy will remain pending additional research.

Racial Disparities in Punishment

On the issue of racial disproportionalities in sentencing, observers of guideline reforms have so far rendered a mixed verdict. For the nation as a whole, racial disparities in incarceration have become more pronounced since the early 1980s, when guidelines were first introduced. Forceful charges have been leveled that the federal guidelines, particularly for drug offenses, and in conjunction with mandatory penalties for drug crimes enacted by Congress, have exacerbated preexisting racial disparities in sentencing. The story appears to be a bit different at the state level. Among state guideline systems, the evaluation literature is scanty on this issue, but most state commissions have reported a modest reduction in racially disparate sentencing following the enactment of guidelines. No guideline jurisdiction claims to have made major headway on the problem of racial disproportionalities in punishment. So far, even under the best case scenario, it appears that sentencing commissions and guidelines can achieve small advances in problems of racial disparity, but commissions and guidelines (as in the federal example) can also act to make such problems worse. No one, in other words, should support guideline reform in the belief that racial equity in sentencing will automatically follow.

Guidelines and Prison Populations

Marvin Frankel hoped that the rationalizing process of commission-based sentencing reform would ultimately lead to what he viewed as more humane sentencing outcomes overall: a reduced reliance on incarceration and increased creativity in the use of intermediate punishments. Writing in the early 1970s, Frankel could hardly have predicted that prison and jail confinement rates in America would in fact increase by more than a factor of four in the next twenty-five years, with most of the confinement explosion occurring after 1980. We must ask how much of the incarceration boom has been attributable to the advent of sentencing guidelines.

Some of it clearly has been. In the federal system, where our knowledge base is deepest, U.S. District Court judges complain regularly that the guidelines (or Congress’s mandatory minimums, or both) force them to impose heavier sentences than they would otherwise have chosen. These claims are consistent with the original legislative and commission intents in promulgating the federal guidelines, as outlined in a 1998 book by Stith and Cabranes: there was widespread political sentiment during the Reagan administration that federal judges had been meting out sentences of undue leniency for many crimes, and the federal guideline reform was directed in large part to preventing that from happening by curtailing the judges’ discretion.

Raw statistics suggest that the designers of the federal system got what they wanted. In the first ten years under the new federal guidelines, from 1987 to 1997, the federal imprisonment rate increased by 119 percent. This growth surge was 25 percent greater than the average increase in imprisonment rates for the nation as a whole during the same period (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998, p. 491, table 6.36). In contrast, in the decade prior to the advent of the guidelines, the federal prison system had been expanding at a much slower pace (23 percent growth in imprisonment rates from 1977 to 1987), far below the national average (77 percent). There is good reason to conclude that the federal sentencing guidelines, in combination with congressional mandatory penalties, ushered in an era of deliberately engineered increases in punitive severity, and shifted gears in federal imprisonment from a slow-growth pace to a fast-growth pace virtually overnight.

At the state level, the relationship between guideline reform and sentencing severity has been mixed, but more consistent with Frankel’s original vision than the federal experience. A number of state legislatures and commissions have created guideline structures with the express purpose of containing prison growth. Minnesota was the first jurisdiction to attempt this, beginning in 1980, by crafting its guidelines with the aid of a computer simulation model to forecast future sentencing patterns. Over the first ten years under the state’s guidelines, imprisonment rates in Minnesota did incline upward, but only by 47 percent—in a period when the nationwide imprisonment rate more than doubled (plus 110 percent). This pattern of some incarceration growth, but slower than the national average, was also seen during the first ten years of the Washington and Oregon guidelines, respectively. Washington’s imprisonment rates increased by 29 percent from 1984 to 1994, while national rates increased by 107 percent. Oregon’s imprisonment rates rose by only 11 percent from 1989 to 1998, while national rates went up 70 percent over the same period. In a 1995 study of sentencing commissions operative in the 1980s, Thomas Marvell identified six state commissions that were instructed to consider prison capacity when promulgating guidelines. In all six jurisdictions, Marvell found ‘‘comparatively slow prison population growth,’’ prompting him to write that ‘‘These findings are a refreshing departure from the usual negative results when evaluating criminal justice reforms’’ (p. 707).

In the 1990s, newer commissions in Virginia and North Carolina have also had notable success in restraining the incarceration explosion. Virginia’s guidelines, for example, were created early in the administration of a new governor who had promised to crack down on violent crime and abolish parole. While allowing the governor to keep his campaign commitments, the new Virginia guidelines have coincided with a 3 percent decrease in the state’s imprisonment rate from 1995 to 1998 (a period in which national rates climbed by 12 percent).

In North Carolina, the state’s imprisonment rate (inmates with sentences over one year, per 100,000 state residents) grew at a fast (19 percent) pace during the first year of the new guidelines, from year-end 1994 to year-end 1995. This can largely be attributed to sentences still being handed down under pre-guidelines law, however, and the temporary growth surge was predicted by the state’s sentencing commission. In the three successive calendar years of 1996 through 1998, as guideline cases have entered the system in greater numbers, North Carolina’s imprisonment rates have fallen every year. Perhaps just as significantly, the state’s guidelines have ushered in deliberate changes in the proportionate share of convicted felons sent to prison and those routed to intermediate punishments. In the first three years under guidelines, the total confinement rate for felony offenders fell from 48 to 34 percent, reflecting the state’s policy judgment that an increased share of nonviolent felons should be sentenced to intermediate punishments. In order to accommodate this change, the commission successfully lobbied the state legislature to provide increased funding for intermediate-punishment programming. At the same time, however, North Carolina’s guidelines have substantially increased the use of prison bed space for violent offenders. In the state’s political arena, the North Carolina commission has won widespread support for its tripartite agenda of severe punishment for violent criminals, the expanded use of intermediate punishments for less serious offenses, and the introduction of planned ‘‘resource management’’ of prison growth.

Slow-growth policy has not been the whole story under state guidelines, however. Like the federal commission, the Pennsylvania sentencing commission was instructed by its legislature to write guidelines that would toughen prison sentences as compared with prior judicial practice— and Pennsylvania’s prisons have grown steadily under the guidelines regime. In sixteen years under guidelines, between 1982 and 1998, Pennsylvania’s imprisonment rate has increased by 244 percent, while the national rate increased by ‘‘only’’ 171 percent. Even in the pioneering states of Minnesota, Washington, and Oregon, the state legislatures (and sometimes the voters, through the initiative process), have acted to toughen sentencing guidelines and other sentencing provisions. In the late 1980s, the Minnesota legislature ordered the state sentencing commission to retool its guidelines to provide harsher sentences for violent crimes, beginning a period of planned prison growth. Accordingly, during the 1990s, Minnesota’s prisons have grown slightly faster than the national average. Washington and Oregon steered similar courses in the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

Two conclusions on guidelines and prison growth emerge from two decades of experience. First, guidelines and computer projections have proven to be surprisingly effective technologies for the deliberate resource management of incarcerated populations—but they are tools that may be used with equal facility to push aggregate sentencing severity up or down. As Michael Tonry noted in 1993, virtually all sentencing guideline systems have been ‘‘successful’’ on this score, if we measure success against what the commission and legislature were trying to achieve. Second, the overall experience of guidelines to date has been that they have sometimes been used to retard prison growth (measured against national trends) and they have sometimes been used to parallel or even exceed the course of prison expansion observable in non-guideline jurisdictions. It is thus difficult to attribute independent causal significance to guidelines as a driving force of the prison boom in the past quarter century. In a number of instances, and whenever called upon to do so, guidelines have been an effective force in the opposite direction.

Purposes at Sentencing

There is little question that sentencing guidelines have succeeded in injecting systemwide policy judgments about the goals of punishment into case-by-case decision-making. How one assesses this achievement turns in part upon whether one agrees with the goals that have been effectuated. For example, the earliest guideline innovations of the 1980s (such as those in Minnesota, Washington, and Oregon) all built their systems on a ‘‘just deserts’’ rationale, scaling punishment severity to the blameworthiness of offenders as measured by current crimes and past convictions. Some observers, like Andrew von Hirsch (an influential proponent of the just deserts theory), would rate such guidelines as enlightened reforms. Others, like Albert Alschuler and Michael Tonry, have charged that the just deserts model is an intolerably one-dimensional approach to punishment decisions.

Moving forward into the 1990s, several states have broadened the menu of underlying purposes that can be written into guidelines. For example, the current Virginia guidelines incorporate the criminological research of criminal careers in pursuit of a policy of selective incapacitation of the most dangerous offenders. Pennsylvania’s guidelines, as revised in the mid1990s, are driven by changing policies through five ‘‘levels’’ of the sentencing matrix. At Level 5 (the most serious cases), retribution and public safety are dominant concerns. Moving downward through the other levels, priorities of victim restitution, community service, and offender treatment become increasingly prominent. And in a recent study, Richard Frase has argued that the Minnesota guidelines, as modified by appellate court decisions and system actors, have come to exemplify the theory of ‘‘limiting retributivism’’ propounded by Norval Morris in which an offender’s blameworthiness sets loose boundaries on available penalties, but consequential concerns such as the prospects for rehabilitation may be used to select a punishment within those boundaries (Frase, 1997). Even the federal guidelines, which claim to be agnostic as to sentencing purposes, can be said to embody a ‘‘philosophical’’ position that most criminal sentences under guidelines should be harsher than those imposed before the guidelines were created.

Data concerning big-picture sentencing patterns reinforce the gathering impression that sentencing commissions have had impact upon jurisdiction-wide punishment policy. Many state guideline systems since the 1980s have reported that, since guidelines were implemented, penalties for violent crimes have been deliberately increased, often at the same time that penalties for nonviolent offenses have been deliberately reduced. Because nonviolent offenses are so much more numerous than nonviolent crimes, even small cutbacks in punishment at the low end of the seriousness scale can free up many prison beds for the more serious criminals. Such results might be applauded on grounds of just deserts, deterrence, or incapacitation. Moreover, the fact that a number of states have had success in manipulating sentencing patterns in this way is one indicator that the policies subsumed in guidelines can have appreciable effects upon sentencing outcomes across the system.

Future Horizons

Sentencing commissions and guidelines are still at an early stage in their institutional history. (Indeterminate sentencing, in contrast, has roots that reach back more than a full century.) Twenty years of experience with sentencing guidelines have not yielded a single model of reform, nor have guidelines yet replaced the indeterminate sentencing structures that remain at work in a bare majority of the American states. In the coming decades, there will almost certainly be continued experimentation and diversification in approach among existing guideline jurisdictions, as among the additional states that will come ‘‘on line’’ with new guidelines in the early twenty-first century.

It is likely that the proven ability of sentencing guidelines (plus computer projections) to manage the growth of correctional populations will induce a steadily increasing number of jurisdictions to invest in some version of guideline reform. But the future of guidelines will also depend heavily upon demonstrable improvements in existing guideline technology along a number of dimensions: system designers will have to solve the problem of finding the right balance between the legal enforceability of guidelines and the role for judicial discretion in sentencing determinations. Guideline drafters must also continue their experiments with incorporating consequential purposes of punishment into sentencing systems, if the policy community is to become convinced that guidelines can do more than instantiate a ‘‘one-note’’ just deserts program. Guideline designers will also continue to be faced with the unsolved riddle of addressing the array of intermediate punishments with guideline prescriptions—building upon a small store of promising initiatives from the late 1990s. Sentencing commissions will also be crucial forums for the ongoing struggle to combat racial disproportionalities in criminal punishment— although these efforts are likely to reinforce our understanding that the sentencing process is only one part of a much larger problem. Finally, the next generation of guideline evolution will depend on far better assessment research than has yet been performed, so that we may better approach such conundrums as the dynamics of charging and plea bargaining within guideline systems, the degree to which guidelines provide room for values of both uniformity and discretion, and the successes or failures of guidelines in furthering their underlying policy objectives. All of these issues, and others, will play out in numerous jurisdictions and in varying permutations in the coming years. Those interested in sentencing guidelines, their established viability, and their potential, must of necessity become ‘‘comparativists’’—with curiosity and knowledge extending outward across multiple systems.

Bibliography:

- ALSCHULER, ALBERT ‘‘Sentencing Reform and Prosecutorial Power: A Critique of Recent Proposals for ‘Fixed’ or ‘Presumptive’ Sentencing.’’ University of Pennsylvania Law Review 126 (1978): 550–577.

- ALSCHULER, ALBERT ‘‘The Failure of Sentencing Guidelines: A Plea for Less Aggregation.’’ University of Chicago Law Review 58 (1993): 901–951.

- American Bar Association. Standards for Criminal Justice: Sentencing, 3d ed. Chicago: ABA Press, 1994.

- Bureau of Justice Assistance. National Assessment of Structured Sentencing. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1996.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics, 1997. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1998.

- Delaware Sentencing Accountability Commission. Truth in Sentencing Benchbook. Wilmington, Del.: Delaware Sentencing Accountability Commission, 1997.

- FRANKEL, MARVIN Criminal Sentences: Law without Order. New York: Hill and Wang, 1973.

- FRASE, RICHARD ‘‘Implementing CommissionBased Sentencing Guidelines: The Lessons of the First Ten Years in Minnesota.’’ Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 2 (1993): 279– 337.

- FRASE, RICHARD ‘‘Sentencing Principles in Theory and Practice.’’ In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, vol. 22. Edited by Michael Tonry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- FREED, DANIEL ‘‘Federal Sentencing in the Wake of Guidelines: Unacceptable Limits on the Discretion of Sentencers.’’ Yale Law Journal 101 (1992): 1681–1754.

- MARVELL, THOMAS ‘‘Sentencing Guidelines and Prison Population Growth.’’ Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 85 (1995): 696– 707.

- Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission. Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines and Commentary. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Sentencing Guidelines Commission, 1997.

- MORRIS, NORVAL, and TONRY, MICHAEL. Between Prison and Probation: Intermediate Punishments in a Rational Sentencing System. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- NAGEL, ILENE, and SCHULHOFER, STEPHEN J. ‘‘A Tale of Three Cities: An Empirical Study of Charging and Bargaining Practices Under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines.’’ Southern California Law Review 66 (1992): 501–566.

- National Center for State Courts. Sentencing Commission Profiles. Williamsburg, Va.: National Center for State Courts, 1997.

- REITZ, KEVIN ‘‘Sentencing Facts: Travesties of Real-Offense Sentencing.’’ Stanford Law Review 45 (1993): 523–573.

- REITZ, KEVIN ‘‘Sentencing Guideline Systems and Sentence Appeals: A Comparison of Federal and State Experiences.’’ Northwestern Law Review 91 (1997): 1441–1506.

- SCHULHOFER, STEPHEN ‘‘Assessing the Federal Sentencing Process: The Problem is Uniformity, Not Disparity.’’ American Criminal Law Review 29 (1992): 833–873.

- STITH, KATE, and CABRANES, JOSÉ Fear of Judging: Sentencing Guidelines in the Federal Courts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- TONRY, MICHAEL. ‘‘The Success of Judge Frankel’s Sentencing Commission.’’ University of Colorado Law Review 64 (1993): 713–722.

- TONRY, MICHAEL. Sentencing Matters. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- TONRY, MICHAEL. ‘‘Intermediate Sanctions in Sentencing Guidelines.’’ In Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 23. Edited by Michael Tonry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- University of Colorado Law Review. ‘‘A Symposium on Sentencing Reform in the States.’’ University of Colorado Law Review 64 (1993): 645–847.

- VON HIRSCH, ANDREW. Censure and Sanctions. Oxford, U.K.: Clarendon Press, 1993.

- VON HIRSCH, ANDREW; KNAPP, KAY; and TONRY, MICHAEL. The Sentencing Commission and Its Guidelines. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987.