View sample criminal law research paper on criminal law and enforcement in England. Browse criminal justice research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In the United Kingdom there are three separate criminal justice systems, one each for Scotland, Northern Ireland, and England and Wales. This research paper will focus on the system in England and Wales, a jurisdiction with a population of fifty-two million people.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In many jurisdictions the criminal laws or penal code can be traced to a key constitutional date when a new system of government was introduced bringing changes to the role of government in general and to criminal procedures in particular. Reforms in the field of criminal law tend to establish new obligations on citizens in the form of the criminalization of an activity, and new constraints on officials in the form of procedures that should be followed when dealing with those accused of crime. In the United Kingdom there have been key constitutional events but no one defining moment has set the foundations of the modern system of criminal justice. In contrast to many modern republics the system has evolved over a very long period of time. One key modern participant in the criminal justice system, the Justices of the Peace, can be traced back to the Justices of the Peace Act 1361. Working alongside the Justices of the Peace, usually referred to in the modern era as magistrates, is the Crown Prosecution Service, an agency established as recently as 1985. Despite the gradual evolution of the key constitutional foundations to the criminal justice system—the rule of law, parliamentary democracy, and freedoms of the individual—since the 1980s there has been a new pace of change as matters of crime, justice, law and order have dominated the political headlines and the actions of both government and citizens.

The history of legislative reform in the field helps to illustrate the growing interest in criminal justice in England and Wales. In the first eighty years of the twentieth century there were only four statutes entitled Criminal Justice Acts, enacted in 1925, 1948, 1967, and 1972. The rate of change increased with Criminal Justice Acts in 1982, 1988, 1991, 1993, and 1994 and a major piece of criminal legislation in each year since 1994: Criminal Appeal Act 1995, Criminal Procedure Act and Investigations Act 1996, Crime (Sentences) Act 1997, Crime and Disorder Act 1998, and the Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999.

In the busy parliamentary session 1999/2000 the following laws were enacted: Powers of the Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act, Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate Act, Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, and the Criminal Justice and Court Services Act.

Such reforms are in part a response to internal pressures for more effective crime control, a desire to protect citizens from bias and unfair procedures, the pursuit of greater administrative efficiency, and technological change. Pressure for reform also results from Britain’s membership in the European Union, which has brought greater cross-jurisdictional cooperation and coordination in an attempt to control cross-European organized crime and to incorporate reforms such as the European Convention on Human Rights (adopted by the United Kingdom in the Human Rights Act 1998). In October 2000 the Convention comes into effect in the United Kingdom and some of the legislation in the 1999/ 2000 parliamentary session was to ensure compliance with the European Convention especially with regard to the surveillance powers of the police (Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000). Heralded as the most significant constitutional changes in recent British history, it is likely to have a widespread impact, especially on aspects of policing, bail, and prison procedures.

The criminal justice system in England and Wales has evolved over a considerable period of time and is a unique mix of traditional and modern institutions, agencies, and procedures. The main features of this system will be outlined briefly, followed by more detailed descriptions of policing and prosecution, criminal courts, sentencing and the penal system, and the governmental and administrative context of criminal justice.

The system of government in the United Kingdom, despite some devolution in recent years, is based primarily in London. The importance of central government funding for the criminal justice agencies and courts means that there is considerable cooperation and uniformity of approach found in the three criminal justice systems in the United Kingdom. The process of harmonization is further enhanced by the increasingly important effect the European Union is having on matters such as cooperation between police forces across Europe to combat transnational crimes (particularly organized crime, money laundering, and drugs).

In the United Kingdom there is no penal code. The sources and interpretation of the criminal laws are to be found in individual Acts of Parliament (statutory sources) and decisions by judicial bodies, in particular the Court of Appeal (case law). Increasingly, decisions of the European Court of Justice have an influence on the operation of the criminal law in all member states of the European Union, including the United Kingdom.

The definition of many criminal offenses can be found in statutes. New laws introduced as bills need to pass through both the House of Commons and the House of Lords before they become Acts of Parliament. Thus the definition of burglary and the maximum punishment for it is defined in the Theft Act 1968. The other principal source of criminal law is common law, which derives not from legislation but from what originally were the customs of the people; these were subsequently used as the basis of decisions made by judges in individual cases. There are some criminal offenses that exist only in the rulings of judges. Murder and manslaughter, for instance, are common law offenses. However, the punishments and partial defenses for these two offenses are set out in statutes—Homicide Act 1957, Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act 1965, and the Criminal Justice Act 1991.

In any criminal justice system it is important to understand the origins of the definitions of criminal conduct, be it through statutory or common law sources. However, it is equally important to appreciate that laws do not enforce themselves; it is therefore necessary to understand the influences on those agencies and participants in the system who interpret and implement the law.

The ‘‘law in practice’’ depends on the activities and decisions of the police, prosecutors, probation and prison officers, professionals (lawyers), and lay participants (magistrates). They do not work from a single document but an array of regulations, requirements, and guidelines as to how they should undertake the task of implementing the criminal law. Thus they will have to refer to specific statutes that relate to their activity and a number of policy documents from central and local government. Furthermore, an agency’s approach to making the law work in practice will be determined by the available resources, as well as the organizational culture that has developed over time regarding the appropriate way of doing business.

Although there are many factors that affect the way the criminal law is enforced in England and Wales it is particularly important to understand the influence of ‘‘adversarial justice’’ and the ‘‘rule of law’’ and how these principles shape the way that criminal justice is defined and implemented.

The defining logic determining the nature of the criminal law and its operation in England and Wales is provided by the adversarial principle. This means that a person is not considered to be guilty of a crime simply on the word of a government official. Conviction in a court requires presentation of admissible evidence that convinces the fact finder—a jury, in the case of serious crimes; for less serious crime, a stipendiary (professional and salaried) magistrate (renamed District Judges in 2000), or a panel of lay magistrates—that the evidence demonstrates the guilt of the defendant ‘‘beyond reasonable doubt.’’ This test of the evidence is in contrast to the much lower standard of proof used in the civil courts, where facts are determined by a judge on the balance of probability (‘‘more likely than not’’).

The nonconviction of a defendant following a trial or an appeal does not mean that the defendant is innocent in the common-sense meaning of the word, that is, he or she had nothing to do with the crime. The adversarial system in England and Wales does not ask whether a defendant is innocent or guilty but only whether they are ‘‘guilty’’ or ‘‘not guilty.’’

The adversarial nature of criminal justice in England and Wales means that in many respects the process of conviction for crime is the same as in the United States. The burden is on the prosecutor to establish that a crime has been committed and that they have sufficient evidence to be able to persuade a jury, beyond reasonable doubt, that the person accused both carried out the act alleged in the crime and was responsible in the sense of being considered blameworthy for the crime. This distinction between committing an illegal act and being blameworthy or culpable, reflects the distinction in English law, as in the United States, between the principles of actus reus and mens rea. Actus reus refers to the events that took place; for example, a named person, on a specified time, date, and place inflicted a knife wound on a named victim. The mens rea refers to the culpability, responsibility, or blameworthiness of the act. If the wound was inflicted by accident and without fault the defendant is not regarded as criminally responsible for the injury.

The principle of adversarial justice has been developed over many centuries, and is designed to protect the liberty and freedom of citizens. Although in any system there is a difference between the principles of a system and the way it operates in practice, government officials are answerable to the law; under this system, known as the ‘‘rule of law,’’ police, prosecutors, courts, and prisons may only make decisions and exercise powers that are permitted through the law.

Although most criminals are convicted through their own admission of guilt and therefore a contested trial about the guilt of a defendant is not necessary, the possibility of a trial is the main safeguard of a citizen who has been wrongly accused of a crime. A citizen who becomes a suspect will normally cooperate to help establish his innocence but should he choose not to the onus is on the police to collect sufficient evidence about the crime and to pass this on to the prosecuting body to make a decision on whether or not to prosecute. The citizen accused of a crime has a number of safeguards that start at the point of questioning and arrest for a crime.

Finally as part of this introduction to the criminal justice system in England and Wales it is important to understand the different classifications of crime. The significance of the classification system is, firstly, symbolic—to indicate society’s distinction between minor and more serious crimes; secondly, to determine the powers of arrest and detention of suspects; and thirdly, for procedural purposes such as deciding whether the offender is dealt with in the magistrates’ court or the Crown Court. The latter deals with more serious crimes.

The Criminal Law Act 1967 abolished the distinction between felony crimes and misdemeanors and introduced the concept of arrestable and non-arrestable offenses. An arrestable offense is defined as any offense for which the sentence is fixed by law (for example, murder, which carries a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment); or for which an offender may be sentenced to imprisonment for a term of five years or more, as well as certain other specified offenses, such as going equipped for stealing. Anyone who is suspected of committing an arrestable offense may be arrested by the police or a member of the public without a warrant. Otherwise, an arrest warrant, signed by a magistrate, is required. Most serious offenses have statutory maxima that exceed five years; for instance, burglary of a dwelling house has a maximum sentence of fourteen years, and the maximum sentence for rape is life imprisonment.

For procedural purposes all criminal offenses are classified into one of three categories: indictable only, triable-either-way, or summary. An indictable-only offense may only be tried in a Crown Court before a jury, and requires an indictment which is a formal document setting out the charges against the person. Offenses in this category include murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, robbery, and rape.

Summary offenses may only be dealt with by summary justice, that is, proceedings in the magistrates’ courts that deal with less serious crimes. Summary offenses are generally those that are punishable by no more than six months imprisonment or a fine of £5,000. These are the maximum sentencing powers in the magistrates’ courts. Examples of summary offenses include motoring offenses such as driving after consuming alcohol or taking drugs, careless driving, and driving without a license. Non-motoring offenses that are summary include less serious forms of assault, drunkenness, and prostitution offenses.

Triable-either-way refers to the third category of offenses, examples of which include burglary, theft, and handling stolen goods, many offenses involving the possession, use, and supply of illegal drugs, and many types of assault. With this category of offense an individual case may be dealt with either in the magistrates’ court or the Crown Court, and hence a pretrial decision becomes necessary, known as the mode of trial decision, which is discussed below in the section on the criminal courts.

But before a case reaches the trial stage there must first be a crime and a suspect. As the case proceeds the suspect becomes the accused and in court the defendant. These pretrial processes are outlined in the following section.

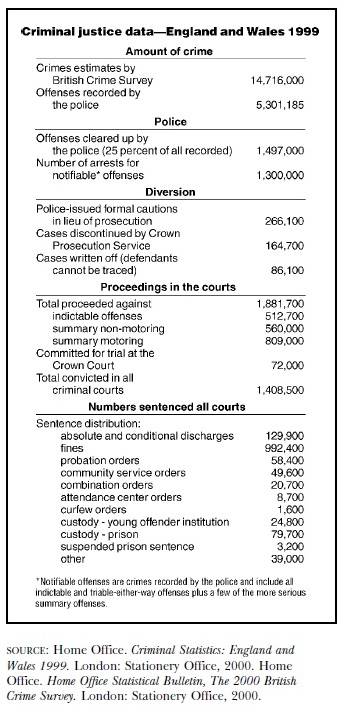

Table 1 gives statistical data for the year 1999, showing case volume at each stage of the criminal process, beginning with estimates of victimization.

Law Enforcement: The Police and Prosecution

The first English police were medieval constables and the unpaid parish constables who were responsible for maintaining the King’s Peace. The urban Watchman had a similar duty. It was not until 1829 that a paid, full-time organized and disciplined police force became established in London: the Metropolitan Police.

Today, the investigation of crime and the arrest, questioning, and charging of those suspected of committing criminal offenses in England and Wales is primarily in the hands of forty-three regional police forces. As of 2000 there were 124,418 police officers and 53,227 civilian staff; the Metropolitan Police is the largest force with 25,485 officers covering the whole of the London area. They are not armed with guns unless working in a special unit such as those assigned to protect diplomats and public officials, or are in armed response units ready to respond to incidents where weapons are used.

The organization of the police in England and Wales is very different from that found either in the United States or in the rest of Europe.

Unlike the United States, there are far fewer police forces and there is no equivalent to the distinctions made between federal, state, county, and city police forces. Unlike many European police forces, there is no national police force answerable to a central government department. However, regional and national police work has been developing in recent decades and there is now a National Crime Squad, set up in 1998, with a cross-jurisdictional role. Furthermore, the Home Secretary, the political head of the Home Office, has considerable influence (although not direct operational control), through the system of central government grants that, along with local council taxes, funds police work. The control of the police is shared between central government, local government, and the police as semi-autonomous professionals.

Special laws and codes govern the operation of police work. Decisions to stop, search, arrest, or question suspects are governed by rules set out in administrative codes pursuant to the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984. The act requires the publication of a series of Codes of Practice to regulate police work when dealing with criminal suspects. Code A deals with the powers to stop and search a suspect in the street; Code B is concerned with the search of premises and seizure of property; Code C relates to the detention, treatment, and questioning of suspects; Code D regulates identification procedures; and, Code E specifies the procedures to be followed for tape recorded interviews with suspects.

The function of the police is to be the main agency responsible for responding to crime, but they also have several other important responsibilities: crime prevention; the maintenance of public order at large events such as royal ceremonies, sporting occasions and public meetings; traffic control, and road safety; custody of lost property; and the provision of emergency service to a variety of persons in need (e.g., those who have lost their door keys, or who have been involved in motoring accidents).

There are other agencies responsible for responding to lawbreaking such as Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise, in the case of smuggling, and the British Transport Police, who deal with crime on the railways and at ports and docks. In contrast to other European countries, the responsibility for most crime is given to the local police force, who have the duty of responding to both major and minor crimes. In England and Wales the prosecutor plays no part at the crime investigation stage, and there is no investigating magistrate as there is in France. Within the police there is a functional division between the detective branch and the regular uniformed police officer. The detective branch is called the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). They respond to major crimes such as murders and have units responsible for investigating more routine crimes such as burglary.

Since 1950 the crime trend has been steadily upward, but it leveled off in the 1990s. Recorded crime figures collected by the police and published annually by the Home Office show that in the year between April 1999 and March 2000 there were 5.3 million crimes recorded by the police. However, a more reliable guide to the extent of crime is provided by the British Crime Survey. Organized by the Research, Development and Statistics Directorate of the Home Office, the survey is now regularly conducted every two years and gives an estimate of the total amount of crime based on a sample of 19,500 respondents. In 2000 it was estimated that there were over 16.5 million crimes reported by victims in this survey. The survey only relates to crimes against the individual and therefore does not include public order offenses (e.g., involving drugs), property crimes committed at the workplace, or crimes involving public bodies such as the railways or tax fraud.

The crime pattern is very different from the United States, with the latest British Crime Survey showing that 22 percent of crimes are violent (homicide, robbery, rape, wounding, sexual offenses) and 80 percent are property crimes. In the twelve months from April 1999 to March 2000 across the whole of England and Wales, there were 765 offenses recorded as homicide (murder, manslaughter and infanticide) and 749 attempted murder offenses recorded (Povey et al.).

The police have a duty to respond to criminal incidents but they are not required to prosecute in every case. Investigations often result in no prosecution because there is not sufficient evidence to charge the suspect, or there may not even be a suspect. Where there is sufficient evidence and a person is charged, the police have the option of not sending the case papers on to the Crown Prosecuting Service, but rather diverting the case from the normal system by issuing an official caution in lieu of prosecution. For this to happen the police should have sufficient evidence against a suspect to be able to have the CPS prosecute the case, and the suspect must admit his or her guilt for the offense. He may then be given a formal caution that is placed on the offender’s record. This system of diversion is used primarily with young offenders; indeed the majority of youngsters aged ten to seventeen are given a caution. For young offenders the use of cautioning was reformed in the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to a system of reprimands and final warnings.

In most cases where the police have sufficient evidence against a suspect, the case papers are forwarded to the prosecuting agency. There are a number of prosecuting bodies for criminal offenses in England and Wales such as the Post Office and the Inland Revenue (responsible for collecting taxation). Since the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985 there has been one agency responsible for the great bulk of routine criminal cases dealt with: the Crown Prosecution Service, known as the CPS.

Prosecutors: Crown Prosecution Service

The CPS was established by the Prosecution of Offences Act 1985, and for the first time provided for a systematic and standardized approach toward prosecution decisions across England and Wales. Before its introduction the police were responsible for most criminal prosecutions, and so procedures and practices varied across the forty-three regional policing areas.

The reform of prosecution was designed to encourage a more cost-effective approach and to promote fairness. The latter was to be achieved by providing for the review of each case by independent and legally qualified prosecutors. Greater consistency and accountability was to be sought through the use of a nationwide code, the details of which are published by the CPS. Each decision to prosecute should only be taken if it satisfies the ‘‘evidential’’ and the ‘‘public interest’’ tests described below. The annual report of the Crown Prosecution Service sets out the Code for Crown Prosecutors and the details of these tests.

The evidential sufficiency test is that the prosecutors must be convinced that the evidence in a case will provide ‘‘a realistic prospect of conviction.’’ To make this judgement they must review the evidence to ensure that it is usable in court and not excluded because of the rules of evidence or because of the way it has been collected. After this they must decide whether the evidence is reliable in the sense of coming from an honest and competent witness who is available to attend court.

The public interest test asks whether it would be in the public’s interest to continue with the prosecution. For example, a case of a very minor offense committed by a defendant close to death due to a terminal illness is unlikely to be prosecuted. The Code for Prosecutors sets out factors that are in favor of prosecution and those that are against prosecuting a case.

A prosecution might be dropped— discontinued in the language of the CPS—for the following public interest reasons: the likely penalty would be very small or nominal (e.g., an absolute or conditional discharge); the crime was committed as a result of a mistake; the loss or harm involved could be described as minor; there has been a long delay between the trial and the date of the offense (except when a case is serious or the delay has been caused by the defendant, or the complexity of the offense has required a lengthy investigation); the victim’s health is likely to be adversely affected by the trial; the defendant is elderly, or mentally or physically ill; the defendant has made reparation to the victim; or there are security reasons for not revealing information that might be revealed during a trial.

The CPS has no investigative function. However, in addition to their main task of reviewing all cases sent to them by the police, they discuss and negotiate with the police on matters of charging standards, for example the offense characteristics that should be taken into consideration when deciding whether a sexual offense should be charged as a rape or as an indecent assault. Finally, a high-profile aspect of their role is they act as advocates to present cases in the magistrates’ courts as prosecutors. In 2000 there were 2,100 lawyers and 3,700 other staff working for the CPS.

Some cases do not go through the standard procedure because of the status of the offender. Special rules of procedure apply to those offenders who are young or are diagnosed as mentally ill. Criminal liability starts at the age of ten in England and Wales. There are different stages relating to the age of the offender that determine both the criminal procedure and the range of dispositions for younger offenders. Under ten years of age the person has no criminal liability; from ten to fourteen they are regarded as children; from fifteen to seventeen as young offenders.

Criminal Courts: Pre-Trial and Trial

Criminal courts include the magistrates’ court, the youth court, the Crown Court, and the Court of Appeal. All routine cases will start in the magistrates’ court with a pretrial decision about granting or refusing bail. Another important pretrial decision concerns the mode of trial for cases where a person has pleaded not guilty and the offense is triable-either-way. As noted previously, some indictable offenses, such as murder and rape, are ‘‘indictable only’’; these must be sent on to the Crown Court. Other indictable offenses are triable-either-way, and these can either be heard by the magistrates’ court or in the Crown Court. The mode of trial decision determines in which court the case will be heard.

In the magistrates’ court, decisions are made about guilt and sentence by lay magistrates or District Judges. Lay magistrates are members of the local community appointed by the Lord Chancellor’s Department. They are part-time and usually sit one day every two weeks. They do not need legal qualifications and typically sit in panels of three, known as the ‘‘bench.’’ Stipendiary magistrates are paid, full-time lawyers with experience of criminal practice. In 2000 there were 30,308 lay magistrates (48 percent of them women), 93 District Judges, and 45 Deputy District Judges. District Judges and lay magistrates have the same powers and jurisdiction. They make pretrial decisions about bail conditions or pre-trial detention (remands in custody), legal representation, and committal for trial or sentence to the Crown Court.

Magistrates in summary trials determine issues of guilt and sentence convicted offenders. They are responsible for the overwhelming majority of criminal convictions and sentencing decisions. They are assisted on matters of law by a legally trained Clerk to the Justices.

The more serious criminal cases are heard in the Crown Court where a judge presides over the trial and a lay jury determines guilt. However, most cases are resolved without a trial because in the overwhelming majority of cases the defendant pleads guilty, induced by the advantage of a reduction in sentence length if a plea of guilt is entered early in the proceedings. When guilt is contested the trial proceeds with the presentation of prosecution and defense evidence and witnesses are subject to cross-examination by opposing counsel.

Criminal liability is often contested not by denial that the events took place but by a claim that the defendant was not responsible for the actions that occurred, or that the actions of the defendant were justified. Such defenses include selfdefense, mistake, duress, provocation, automatism (involuntary act), or diminished responsibility. These defenses can sometimes persuade the jury or District Judges that the person is not guilty; even if the defendant is convicted, such defenses may suggest mitigating circumstances resulting in a less severe sentence. Where a suspect is below the age of criminal responsibility or is certified as mentally ill, he or she will not be regarded as responsible under the criminal law for their actions. The decision on guilt is made by a twelve-person jury, who are able to make a majority verdict (10–2 or 11–1) if, after a length of time, a unanimous verdict is unlikely.

The judge’s role is threefold: to ensure a fair trial, for example, by excluding unreliable evidence; to sum up the evidence at the end of the trial and summarize the legal issues for the jury before they make a decision; and, if the defendant is convicted, to decide on the sentence. The judge should act as the umpire and ensure a fair trial. If the evidence is insufficient, unreliable, or unfair the judge can order a directed acquittal.

In criminal cases, appeals can be made against conviction, against the sentence, or both. Appeals against decisions made in the magistrates’ court are heard by the Crown Court; routine appeals against conviction or sentence in the Crown Court are heard in the Court of Appeal.

Where a serious miscarriage of justice is alleged, a review body has the role of deciding whether to refer the case back to the Court of Appeal. The Criminal Cases Review Commission was established by the Criminal Appeal Act 1995, and its function is to review suspected miscarriages of justice. It can refer a conviction, verdict, or sentence to the Court of Appeal if it feels there are grounds for re-examining the case. It came into operation in 1997 and by March 2000 had made eighty referrals to the Court of Appeal. The leading reasons for referrals are breach of identification or interview procedures; use of questionable witnesses; problems of scientific evidence such as DNA or fingerprints; nondisclosure by the prosecution of evidence that could have helped the defense case; and problems with other types of evidence such as alibis, eyewitnesses, and confessions.

Cases involving defendants above the age of legal responsibility—ten years of age—who have not yet reached the age of eighteen will normally be heard by the youth court, which is attached to the magistrates’ court; the public is not allowed to observe events in the youth court. For certain grave crimes such as murder, a child or youth will have their case heard in a Crown Court adapted in some measure to the needs of children.

Sentencing and The Penal System

The aims of sentencing were set out in a 1990 Home Office report that preceded the Criminal Justice Act 1991. The law sought to provide a sentencing framework for those making sentencing decisions in the courts and those responsible for operating the penal system (the Probation Service, Prison Service, and Parole Board). The report stated:

The first objective for all sentences is the denunciation of and retribution for the crime. Depending on the offence and the offender, the sentence may also aim to achieve public protection, reparation and reform of the offender, preferably in the community. This approach points to sentencing policies which are more firmly based on the seriousness of the offence, and just deserts for the offender. (Home Office, 1990, p. 6)

Sentencing decisions for those convicted of a crime are made by the magistrates in magistrates’ courts and the judge in the Crown Court. Decisions about individual cases are made with the help of voluntary guidelines in the case of magistrates and presentence reports provided by the Probation Service. The general sentencing framework is determined by the maximum sentences set out in statutes, a few mandatory sentences (such as life imprisonment for murder), and statutory criteria such as those related to the use of custody. A major influence on judges in the Crown Court are the decisions made by the Court of Appeal and particularly the Court of Appeal Sentencing Guideline Cases.

In England and Wales in recent decades the sentencing process has been reformed with the aim of reducing disparities, promoting consistency, and reassuring the public about the purpose of sentencing. But the reforms have not introduced the degree of constraint found in those parts of the United States where the courts are subject to sentencing guidelines (as in Minnesota) or determinate sentencing laws (as in California). The constraints on judges and magistrates in England and Wales are provided by statutory factors, the appeal process, judicial training, and the use of voluntary guidelines by magistrates.

Appeals against sentences are allowed, with appeals from the magistrates’ court being heard in the Crown Court and the appeals against sentence in the Crown Court being heard by the Court of Appeal. Only the defendant has the general right of appeal, although in 1988 the Attorney General was given the right to appeal unduly lenient sentences for grave offenses that are triable only in the Crown Court.

The twentieth century has witnessed an increase in the range of available penalties; the abolition of corporal and capital punishment; and the introduction of a variety of community sentences. The death penalty was abolished for homicide in 1965. For adults convicted of murder the mandatory sentence is life, although this rarely means a person spends the rest of their life in prison. The average length served in prison on a life sentence before first release under license (parole) is fourteen years, but release is not automatic. A life sentence is indeterminate, not fixed; release from a mandatory life sentence is authorized by the Home Secretary following recommendations of the Parole Board and consultation with the Lord Chief Justice and the trial judge. A life sentence is also possible (but not mandatory) in a number of other grave offenses such as rape and robbery.

All prisoners given a fixed prison sentence are eligible for remission. Remission is automatic for those sentenced to less than four years at the halfway point of the sentence so that a person sentenced to six months will be released after three months and a person sentenced to three years will be released after eighteen months. If the defendant had time spent on remand in custody this time will be taken into account as time served.

Some inmates will be supervised in the community following their release. A distinction is made between those who are sentenced to over twelve months but less than four years. These will be supervised in the community after release from custody for a period equal to a quarter of their sentence length. Those sentenced to less than twelve months will not be subject to supervision in the community after release. Where supervision in the community is required it is undertaken by the Probation Service; there is not a separate parole service as there is in the United States.

Those sentenced to periods of four years and greater have their sentence remission counted differently. They are allowed one-third off their sentence length but may apply for parole after serving 50 percent of their time. Thus a person sentenced to twelve years becomes eligible to apply for parole after serving six years, and must be released after eight years. The decision on whether to release the inmate between the six- to eight-year period is made by the Parole Board. Compulsory community supervision applies to these released inmates.

Home Detention Curfew was introduced in 1999 to allow inmates early release up to sixty days before their automatic release date. During the period they are subject to a curfew and electronic monitoring.

The prison system held on average 64,631 prisoners a day in the year 1999/2000. This is five hundred more than the prison system was designed for, and thus overcrowding occurred in some, mainly male, local prisons (Prison Service).

The same range of community penalties are available for adults in the magistrates’ courts and the Crown Court. In 1907 probation was introduced; in 1972 community service orders became available; and in 1991 the combination order and curfew order were established as sentencing options. However, the typical sentence is a fine, accounting for 992,400 out of 1.47 million sentenced offenders in 1999 (see Table 1). To promote the use of community sentences the Criminal Justice and Court Services Act 2000 introduced Drug Abstinence Orders and Exclusion Orders and renamed Probation Orders as Community Rehabilitation Orders; Community Service Orders became Community Punishment Orders; and Combination Orders were redesignated as Community Punishment and Rehabilitation Orders.

Governmental and Administrative Context of Criminal Justice

The Parliament at Westminster is the source of all legislation that covers criminal procedure and criminal law. The system of case law means that the courts are the source of common law. Increasingly European Community regulations and decisions by the European Court of Human Rights are coming to affect criminal procedure in England and Wales.

Although there are similarities between the principles of the criminal justice system in England and Wales and the United States, especially with respect to the adversarial system of justice, there are important differences in the system of government. There is far less separation of power in the British constitution than in the United States. The executive and legislative branches of government are brought closely together through the parliamentary system of government whereby the executive branch of government is formed by the political party with a majority of seats in the House of Commons. The General Election simultaneously determines the political party that will form the government and gives the governing party control of the legislature. Thus the constitution allows for a considerable degree of overlap between the executive and legislative branches. Secondly, the administration of government in England and Wales is more centralized than in the United States. There are no separate states with their own laws, jurisdictional authority, and criminal procedures.

The major government offices are based in London. The key government departments are the Home Office and the Lord Chancellor’s Department. The Home Office has overall responsibility for policing, prisons, and the probation service. The head of the Home Office is called the Home Secretary who has political responsibility for crime policy in England and Wales. For example, the Home Secretary sets the key objectives and priorities for the police. The Lord Chancellor’s Department has responsibilities relating to the judiciary, and the head of this department, the Lord Chancellor, is both a political appointee and the head of the judiciary in England and Wales.

Most of the public sector employees of the criminal justice system work for the central government; this includes 177,645 employees (officers and civilians) of the police forces, 43,088 employees of the Prison Service, and 7,200 probation officers.

The pressure to adopt a more centralized and systematic approach to crime has been apparent since the 1980s. Government policies have encouraged a greater degree of interagency cooperation within regions. The Criminal Justice Consultative Council was established in 1991 to promote greater awareness of the problems facing the different agencies in the system. Increased cross-regional coordination of law enforcement was the purpose behind the establishment of the National Crime Squad, set up by the Police Act 1997. The National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) was established in 1992 to coordinate law enforcement efforts with regard to organized crime, illegal immigration, drugs, and counterfeiting.

A comparison of the criminal justice systems in the United Kingdom and the United States would lead to the correct conclusion that the system in England and Wales is more centralized and dependent on central government. However, there are some important counterinfluences that make the role of central government less powerful than first appears to be the case.

First, there are strong regional divisions and responsibilities based primarily on the big metropolitan cities and the old shire counties. For instance, the organization of the police is based on forty-three police forces with jurisdictions that are geographically determined primarily by the old county boundaries of England and Wales such as Hampshire and Essex. An important role is played by local government (cities, boroughs, and counties), especially with regard to crime prevention work in the community, and these governments play a vital role coordinating interagency strategies in response to youth crime.

Second, the independence of the judiciary is a real and effective constraint on the activities of the executive branch of government. The legal professions, represented by the Law Society (representing solicitors) and the Bar Council (representing barristers, or trial lawyers) are powerful protectors of the liberties of the citizen.

Third, the involvement of nonprofessional lay participants such as magistrates, lay visitors to police stations, the Board of Visitors responsible for the oversight of prisons, and Victim Support volunteers ensures that the system is not solely accountable to central government. These nonprofessional groups include well over fifty thousand citizens who each week play a vital role within the system, and bring with them a degree of independence in their approach to issues of crime and justice.

Fourth, there is vociferous and well-organized system of pressure and lobby groups based on the voluntary sector, such as the Magistrates’ Association, who help to shape policy developments. These voluntary associations also play a role in cooperative projects and schemes to help offenders and victims (Victim Support). Two key volunteer organizations in the penal system are the Howard League for Penal Reform and NACRO (National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders).

Fifth, interest groups play a part in the process of shaping criminal justice policies. The existence of powerful trade unions such as the Prison Officers Association and the Police Federation ensure that the views of these officers are heard in public debate. In recent years the advance of the private sector has become apparent with privately run prisons operated by commercial companies such as Group 4. An extensive private security industry includes companies such as Securicor and Wells Fargo. It is estimated that 400,000 people are employed in the private sector associated with the criminal justice system in England and Wales.

Finally, the European Court of Human Rights has become increasingly important as the final court of appeal for those citizens who feel that the system has infringed their rights. The international dimension of criminal justice is bound to increase under the influence of greater European harmonization of laws and cooperation between law enforcement agencies; organizations such as Europol (policing agencies) and Eurojust (prosecutors) have already linked officials in different European countries.

Is a European criminal justice system likely to come into being in the near future? Given the great diversity of legal systems, the range of criminal justice agencies in the countries that form the European Union, and the variations in crime problems and public attitudes to law and order, it will be some time before it would be realistic to talk of a single European criminal justice system with harmonized laws and procedures that are the same regardless of where a suspect is arrested in Europe. On matters of crime and justice, parochial attitudes are very difficult to overcome, although the experience of the United States has shown that greater harmonization is not an impossibility. Whether it is desirable or not is a very different question.

Bibliography:

- ASHWORTH, ANDREW. ‘‘The Decline of English Sentencing and Other Stories.’’ In Sentencing and Sanctions in Western Countries. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- BARCLAY, G., ed. Criminal Justice Digest 4: Information on the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales. London: Home Office, 1999.

- DAVIES, MALCOLM; CROALL, HAZEL; and TYRER, JANE. Criminal Justice: An Introduction to the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales, 2d ed., London and New York: Longman, 1998.

- Home Office. Crime, Justice and Protecting the Public. London: Home Office, 1990.

- Home Office. Criminal Statistics: England and Wales 1999. London: Stationery Office, 2000.

- Home Office. Criminal Statistics: England and Wales. London: Stationery Office. Published annually.

- Home Office. A Guide to the Criminal Justice System in England and Wales. London: Home Office, 2000.

- KERSHAW, C.; BUDD, T.; KINSHOTT, G.; MATTINSON, J.; MAYHEW, P; and MYHILL, A. The 2000 British Crime Survey England and Wales. Home Office Statistical Bulletin, issue 21/98. London: Home Office, 1998.

- POVEY, D.; COTTON, J.; and SISSON, S. Recorded Crime Statistics. Home Office Statistical Bulletin 12/00. London: Home Office, 2000.

- Prison Service. H M Prison Service Annual Report and Accounts April 1999 to March 2000. London: Stationery Office, 2000.

- SISSON, S.; SMITHERS, M.; and NGUYEN, K. T. Policing Service Personnel. Home Office Statistical Bulletin Issue 15/00. London: Home Office, 2000.