Sample Skill Training Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. Introduction

More than 200 years ago, Adam Smith argued that the incentives to invest in workers’ skills are similar to the incentives to invest in physical capital. Workers or their employers invest in skills if the benefits or ‘returns’ from this investment exceed its cost. These investments manifest themselves in increased worker productivity. When workers receive the returns from investments in skills their wages, salaries and fringe benefits rise. When employers receive the returns from these investments their profits rise.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

This research paper describes how the concept of ‘human capital’ anticipated by Adam Smith applies to decisions to acquire more schooling or to invest in vocational skills on the job. The idea is that workers and their employers act as if they evaluate investments in skills using the same cost-benefit calculus that they would use when assessing the net benefits from any other investment. The familiar forces of supply and demand influence these decisions. As more individuals acquire schooling, the supply of better-educated persons increases. All other things being equal (i.e., holding demand constant), the number of better educated persons employed increases, as does national output, but wages or salaries for this class of workers decline. Similarly, as more persons become educated, the supply of less educated persons declines and this group of workers’ wages tends to increase.

An important difference between investing in workers and investing in new plants and equipment is that individuals can move. An employer that provides generous training opportunities to its employees may find that it has provided generous training opportunities to other employers’ workers. This problem creates an important disincentive for employers to train their employees. Accordingly, this research paper focuses on the incentives for workers to acquire vocational skills either while in school or on-the-job and then discusses the evidence on the incidence, duration, and costs of training. The last section of this research paper comments on circumstances where these incentives may be insufficient and where the public sector might productively influence private training decisions.

2. Incentives To Invest In Education And Training

Economic theory predicts that competitive markets provide workers and employers with incentives to invest in training (Becker 1980). Individuals acquire more schooling because the value of future benefits associated with that schooling exceeds its costs. For the individual who decides to go to school, the benefit from schooling is the difference between her earnings with the schooling minus what her earnings would have been without the additional schooling. Individuals realize these earnings gains from schooling during each year of their working lives. Because individuals reap these gains in the future, they should be appropriately discounted to account for the ‘time value of money.’

Most analyses of the cost of schooling focus on the direct costs and the opportunity costs of schooling. The former costs consist of the value of resources used to teach students new skills. The value of these resources to society is the value of what they would produce if they were used in some other activity. Analysts often estimate this amount by the (unsubsidized) cost of tuition, supplies, and transportation associated with attending school.

Opportunity costs are another important cost of schooling, especially for adults. This cost arises because when a person is in school they may not be working, or if they are working, they are likely to be working in a job in which their productivity is relatively low or they are working fewer hours. Consequently, schooling is associated with lost earnings for the individual and lost output for the economy. Analysts usually measure this cost by a person’s wage times the number of additional hours that she would work had she not gone to school. Because older workers are more productive, the opportunity cost of schooling is higher for them than it is for teenagers and young adults.

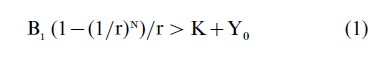

The decisions of individuals about whether to attend school depend on the relative magnitudes of these varying components of the benefits and costs of schooling. A simple model of this decision process is instructive for its empirical implications. Suppose the earnings gain due to schooling is constant throughout a worker’s working life and is denoted by Bi. The subscript associated with the term Bi indicates that the benefits from schooling vary among individuals in the population. If an individual is contemplating attending and completing college, then we can think of the term Bi as being the college wage premium. Suppose further that the worker’s career has N years remaining, future gains are discounted at a rate of r, the direct costs of schooling are K, and earnings during the schooling period would have been Y . Under these conditions the decision to attend school depends on whether the benefits exceed its costs as is summarized by the following expression:

This expression implies that people who attend school (a) anticipate higher gains than those who do not attend; (b) anticipate working longer after completing school; and (c) face relatively low direct and opportunity costs of schooling (Heckman et al. 1999).

The foregoing expression explains why more academically able persons attend school and acquire more years of schooling than do their less able counterparts. These persons acquire new skills more efficiently and as a result experience a larger increase in their productivity as a result of their education. Young people also should be more likely to attend school than older persons for two reasons. First, they have more years left in their working lives during which they can realize a return on their investment. Second, they have less labor market experience and can not earn as much if they were to go to work. The expression given in (1) also implies that public subsidies of education should increase enrollments in schooling because they lower an individual’s cost of schooling. Such subsidies should encourage persons to enroll in school who would not have otherwise attended school, because their anticipated gains from schooling, Bi, are relatively low, or they are older, or they face a relatively high opportunity cost of schooling.

The familiar forces of supply and demand for workers with differing levels of schooling influence the decisions of individuals to attend school. If schooling is a good investment (i.e., the inequality given by (a) holds), more persons attend school. Because of the increase in the supply of better-educated workers, the prevailing wages for these workers decline and there- fore so does the gain from schooling, Bi. As the gain from schooling declines, enrollment rates also decline. In this way, market forces determine school enrollment.

We observe an example of this adjustment process in the United States during the 1970s, when young college educated workers experienced a marked decline in their relative earnings. These individuals were from a large, well-educated birth cohort that entered the workforce at the same time that labor force participation rates for women were increasing rapidly. The increase in supply pushed down their earnings. A similar pattern was observed in Korea and Japan during the 1980s, when the ratio of college-educated to high school educated workers’ earnings declined (Kim and Topel 1995).

The decision to invest in skills on-the-job involves the same cost-benefit analysis as that given by expression (1) above. The difference between the decisions to invest in schooling and in on-the-job training is that employee and employer interests are not necessarily the same. When the skills that workers acquire on the job are easily transferred to other employers, the incentives of firms to invest in their employees’ skills are greatly diminished. The employer can profit from its training investments only if the employee stays with the firm. In order for an employer to have sufficient incentive to invest in employee skills, it needs some device that ties the worker to the firm. One way that companies can foster long-term relationships with their employees is to offer them some form of deferred compensation.

Another solution to the problem of providing on-the-job training to employees is for the worker to pay for the training. In principle, an employee could sign a contract in which she agrees to compensate the employer for training costs if she were to leave prior to some specific date. But another way to achieve this outcome is for the employee to pay for the training by accepting a lower salary during her early years on the job. This outcome would occur if essentially two market transactions take place when a firm hires a worker. The first transaction is the familiar one in which an individual sells her time for a wage. The second transaction results because workers seek training opportunities from employers (Rosen 1972). They buy this training from employers by accepting lower pay. Accordingly, the wages and salaries that we observe workers receiving are the difference between the value of their time and initial skills that they bring to the workplace minus the cost of the training provided by the employer.

3. Sources Of Training In The Private Sector

There is a great deal of information about the amount of schooling obtained by people in countries throughout the world. In the United States, the web pages for the US Departments of Education and of Labor include a wealth of information on school enrollment, educational attainment, and academic performance by different groups in the population. By contrast, much less is known about sources of training outside of school. Estimates of the amount of training acquired on-the-job usually are imprecise.

There are several reasons why we do not know enough from existing data sources about the incidence and intensity of vocational training received by the workforce. First, most data sources contain only unrefined measures of the incidence, the source, and duration of training as reported by the employee. These data sources do not include measures of the costs of training other than the employee’s wage. Even less common are employer reports of training activity that are representative of the experiences of the workforce. Further, if more effort were made to survey employers about their training expenditures, there remains the problem that many firms do not keep separate accounts on the resources spent on employee training.

A second reason that we do not know as much about on-the-job training as we do about schooling is that such training is conceptually difficult to measure. If firms provide training in the context of a formal program, it is relatively easy to characterize the content of the program and to measure the number of hours spent in training and the dollars spent on the program. However, much private sector training is provided informally, especially in the United States (Lynch 1994). Employees acquire new skills by trial and error, by watching their peers and supervisors perform their jobs, or while they are mentored by other employees. Such training represents an investment, because the employer incurs the costs associated with a new employee’s lower productivity. These costs include the wages employers pay employees to shadow other workers, the lost output associated with the time that other workers spend away from their jobs, and the lost output associated with employee errors.

In one of the few large surveys of employers, US employers reported that only 12 percent of the training that they provided their most recent hires during their first three months on the job occurred in a formal setting. The majority of time in training occurred while the employee was on the job (Barron et al. 1989). Surveys of representative samples of the US labor force also underscore the importance of informal training in the workplace. Among individuals who responded to special supplements of the US Bureau of the Census’ Current Population Surveys (CPS) and who said that they needed specific skills in order to qualify for their current (or last) job, 47 percent reported that they acquired this training informally either on another job with the same employer or from a previous employer. Further, among those reporting that they had acquired training while in their current jobs, 37 percent said that those skills had been acquired informally while on the job (Ashenfelter and LaLonde 1997).

4. The Incidence Of Skill Training In The Workplace

In spite of existing data sources, do we know roughly how often and how much training workers acquire after they leave school? Vocational training is relatively common. In the US for example, the CPS indicates that a majority of workers are employed in jobs that require specialized training. Among these workers, 41 percent reported that they had received additional training while in their current job.

An important and consistent finding in the literature on the incidence of training is that there is a strong positive correlation between an individual’s formal schooling and whether she reports having received on-the-job training (Lillard and Tan 1992; Lynch 1992; Altonji and Spletzer 1991). This relationship between worker skills and the propensity to receive training is not unique to the United States. Studies of worker training in Great Britain and Germany also reveal a positive correlation between employees’ formal schooling and whether they have received formal on-the-job training (See Nickell 1982; Greenlaugh and Stewart 1987; Booth 1991; and Pischke 1996). These findings hold especially for formal company programs, and training received off the job but paid for by the employer. The relationship between schooling and the incidence of skill training appears to be less strong when the training is provided informally. But, this result may simply underscore the difficulty we have in identifying and measuring informal training.

The positive relationship between schooling and the receipt of training suggests that training is more productively provided to more skilled or academically able people. In the context of expression (1), research indicates on-the-job training is more productive when firms provide it to individuals with larger gains (Bi) from schooling. Studies show that even among persons who have attained similar levels of schooling, the better educated among them receive more training (Altonji and Spletzer 1991). One nationally representative US survey found that less than 12 percent of young economically disadvantaged persons reported receiving vocational training during the previous 18 months. By comparison, the percentage of young adults in the population at large that reported receiving training during the same period was approximately 25 percent (Lillard and Tan 1992).

The strong complementarity between workers’ prior skills and on-the-job training also has implications for workforce policy. People with limited or poor quality schooling are likely to receive limited additional training once they enter the labor force. Governments can not expect that private firms will compensate for deficiencies in the public education system by providing training in basic skills to their employees. Instead, research suggests that employers would increase the incidence of skill training if the educational attainment and general skills of the workforce rose.

5. Estimates Of The Amount Invested In Training

Although the available measures of training investments are not very precise, it is still possible to estimate the amount invested in training each year. The most direct approach is to add together the value of the time that workers spent being trained or training others plus the resource costs associated with providing the training (Mincer 1994). This approach requires detailed information on the employees’ use of time. On occasion such information is collected from workers in the form of a diary, in much the same way that government statistical agencies collect information for consumer expenditure surveys. Given the costs of gathering this type of data it is not often used to estimate the cost of training on an economy wide basis.

A less expensive approach for estimating the annual cost of on-the-job training is to infer the amount of training received by employees from the rate of their earnings growth during their careers (Mincer 1962). This inference relies on an important empirical regularity. The wages and earnings of individuals rise with the amount of labor force experience that they have acquired, but rise at a decreasing rate. When individuals are young, their wages and salaries rise relatively rapidly as they acquire more work force experience. But as they move into middle age the rate of growth in their earnings slows and for some groups stops all together. This rise in earnings indicates that young workers become more productive as they get older.

If we assume that all of the increase in workers’ earnings results from training received on-the-job during their careers, and if we assume that investments in training earn a ‘normal’ rate of return, then we can infer the total investment in private training each year from the growth in workers’ earnings. In keeping with these assumptions, several studies report that employees’ wage growth is largest when they report that they are receiving training in their current positions. As they begin to report that they are receiving less training in their current jobs, their wage growth also slows (Brown 1989). Mincer’s and Higuchi’s (1993) study of US and Japanese manufacturing industries finds that workers in industries in which firms provide more training also have earnings that rise more rapidly with years of service. In another study of professional employees in a large US manufacturing firm, about 18 percent of the growth of employees’ earnings is explained by participation in the company’s formal on-the-job training programs (Bartel 1992).

If workers receive training that raises their general skills, the foregoing approach probably overstates private investments in skill training. There are other reasons that workers’ earnings grow during their careers besides training. For example, workers change jobs frequently, especially early in their careers, in order to obtain better pay. This ‘job matching’ process leads to higher worker productivity as workers’ skills become better matched with the tasks demanded by employers. But the resulting rise in worker productivity does not come about from investments in training, but rather from investments in ‘job search.’

By contrast, the indirect approach to estimating annual training investments could understate the total investment in training if some of the skills that workers acquire are ‘firm-specific.’ These are skills that raise workers’ productivity with their current employer, but not elsewhere. Because workers can not transfer these skills to another firm, it is more likely that the employer is willing to invest in training. Under these circumstances, the wage gains from training should be smaller than the productivity gains. This gap between workers’ wage gains and their productivity gains indicates that the employer receives a return on its investment in training. Among the few studies that examine the relationship between training and productivity, at least two of them suggest that the effect on worker productivity of training received during the first few months on the job is twice as large as its effect on wages (Barron et al. 1989; Bishop 1994). This finding suggests that a significant component of vocational training may involve ‘firm-specific’ skills provided by the employer.

Studies of on-the-job and vocational training in the United States suggest that both the direct and indirect approaches yield similar estimates of annual investments in training. According to these studies, the annual cost of vocational training amounts to between $150 and $200 billion per year. By comparison, the annual costs of formal schooling in the US, including the forgone earnings while individuals are in school, have been estimated at around $500 billion dollars.

6. The Impact Of Training On Workers’ Earnings

Many studies find a significant positive correlation between the incidence and the amount of training received by employees and their wages. This correlation might indicate that on-the job training yields positive returns. But it also could simply indicate, as discussed above, that individuals who are more productive and highly paid also are more likely to receive training from their employers. Distinguishing between these two hypotheses is difficult. Employers do not provide training randomly to their employees nor do workers randomly acquire training on their own. However, studies that attempt to address this difficulty continue to find a positive relationship between measures of the incidence and duration of training and workers’ wages. Research suggests that the gross returns to wages from a year’s worth of vocational training is approximately 10 percent per year or more (Mincer 1994).

This evidence on the impact of skill training suggests that the returns from on-the-job training are comparable if not larger than the returns from formal schooling. One explanation for this finding is that despite analysts’ best efforts, they still have not satisfactorily accounted for unobserved attributes that simultaneously influence wages (or productivity) and the propensity to receive training. There are several reasons, however, to expect that the returns from skill training to be larger than the returns from formal schooling. First, the returns from formal schooling may be lower than the returns from training because some schooling costs probably are better characterized as consumption instead of as an investment. Second, because workers acquire some specific skills and at the same time may leave the firm, the returns from training need to be larger than the returns from schooling in order to compensate both the worker and the employer for the risk associated with turnover.

Finally, as new technologies are introduced some skills may become obsolete. One study suggests that the value of workers’ vocational skills may depreciate by as much as 10 percent per year (Lillard and Tan 1992). As a result, if workers’ skills are likely to depreciate, the returns from vocational skills must be larger in order for there to be sufficient incentive to invest in training.

7. Concluding Remarks

Increased interest in the incentives to invest in vocational skills has coincided with several economic developments during the last two decades of the twentieth century. First, the rise in earnings inequality in the United States and Great Britain appears prompted in part by a decline in employers’ demand for the services of relatively unskilled workers (Katz and Murphy 1992). The long-term prospects of many of these individuals is poor because students in these countries appear to end their formal schooling less skilled and ready to learn than their counterparts in other industrialized nations (Berg 1994). Second, a large number of workers displaced from traditional sectors of industrialized economies have suffered long-term earnings losses (Jacobson et al. 1993). As these displacements spread to the services sectors, interest in the feasibility of retooling such workers has increased. Finally, the low unemployment rates during the late 1990s in North America have pressured employers to put greater emphasis on training their existing workers rather than to expect to be able to hire employees with the required skills.

Some commentators and researchers argue that these developments require attention from the public sector because employers and their employees lack adequate incentives to invest in skill training (Lynch 1994). To be sure, as this research paper has described, a well-functioning competitive labor market provides incentives for workers to acquire and their employers to provide skill training by compensating workers with higher wages and firms with increased profits. Individuals face similar incentives when deciding whether to acquire more schooling. But there may be instances when these incentives are insufficient. Imperfect capital markets may restrict access to funds, which prevent individuals and firms from making otherwise productive investments in skills. These instances also arise when vocational skills can be easily transferred from one employer to another. The possibility that employers can poach other firms’ employees diminishes incentives to invest in employee training. Likewise, imperfect or asymmetric information about workers’ skills also may reduce incentives to invest in vocational training. Few studies address this possibility, but one that does suggests that skills are not fully ‘portable’ at least during the first year on the job (Bishop 1994). If it is difficult for workers to reveal their skills to a potential employer, employees may invest less in new skills than they would otherwise.

The merits of policies that require the public sector to play a role in private training decisions depend on whether companies and their employees underinvest in training. Such a view remains open for debate. As discussed above, there are several reasons why such a debate will be difficult to resolve. First, measures of vocational training tend to be unrefined and often not comparable among studies of firms in the same country, much less studies of different countries. Second, some components of training, especially informal on-the-job training, are conceptually difficult to measure. Evidence discussed here indicates that such informal training is an important source of training, especially in the United States. Finally, even if researchers concluded there has been too little investment in vocational training in industrialized economies, the conceptual difficulties associated with measuring different types of training indicate that it will be hard to enforce employer mandates to provide more training (Brown 1990).

Bibliography:

- Altonji J G, Spletzer J R 1991 Worker characteristics, job characteristics, and receipt of on-the-job training. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 45: 58–79

- Ashenfelter O, LaLonde R 1997 The Economics of Training. In: Lewin D, Mitchell D, Zaidi M (eds.) Handbook of Human Resources. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT

- Barron J M, Black D A, Lowenstein M A 1989 Job matching and on-the-job training. Journal of Labor Economics 7: 1–19

- Bartel A P 1992 Training, wage growth and job performance: Evidence from a company database. Working Paper No. 4027, National Bureau of Economic Research, March

- Becker G S 1980 Investment in human capital: Effects on earnings. In: Human Capital, 2nd edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 15–44

- Berg P 1994 Strategic adjustments in training: A comparison with Germany. In: L Lynch (ed.) Training and the Private Sector. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 77–107

- Bishop J 1994 The impact of previous training on productivity and wages. In: L Lynch (ed.) Training and the Private Sector. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 161–99

- Booth A 1991 Job-related formal training: Who receives it and what is it worth? Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 53(3): 281–94

- Brown C 1990 Empirical evidence on private training. In: Ehrenberg R (ed.) Research in Labor Economics, Vol. 11. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 97–113

- Brown J N 1989 Why do wages increase with tenure? On-the-job training and life cycle wage growth observed within firms. American Economic Review 79: 971–91

- Greenlaugh C, Stewart M 1987 The effects and determinants of training. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 49: 171–90

- Heckman J, LaLonde R, Smith J 1999 The Economics and Econometrics of Active Labor Market Programs. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 3, Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam

- Jacobson L, LaLonde R, Sullivan D 1993 The Costs of Worker Dislocation. W E Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, Kalamazoo, MI

- Katz L, Murphy K M 1992 Changes in relative wages, 1963–1987: Supply and demand factor. Quarterly Journal of Economics 107(1): 35–78

- Kim D, Topel R 1995 Labor Markets and Economic Growth: Lessons from Korea’s Industrialization, 1970–1990. In: Freeman R, Katz L (eds.) Differences and Changes in Wage Structures. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Lillard L A, Tan H W 1992 Private sector training: Who gets it and what are its effects? In: Ehrenberg R (ed.) Research in Labor Economics, Vol. 13, JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 1–62

- Lynch L M 1992 Private sector training and the earnings of young workers. American Economic Review 82: 299–312

- Lynch L M 1994 Payoff to alternative training strategies at work. In: R Freeman (ed.) Working under Different Rules. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

- Mincer J 1962 On-the-job training: Costs, returns, and some implications. Journal of Political Economy 70(Supplement): 50–79

- Mincer J 1994 Investment in US education and training. Working Paper No. 4844, National Bureau of Economic Research, August. Cambridge, MA

- Mincer J, Higuchi Y 1993 Wage structures and labor turnover in the United States and Japan. Journal of Japanese and International Economics 2: 97–133

- Nickel S 1982 The determinants of occupational success in Britian. Review of Economic Studies 59: 43–53

- Pishchke J 1996 Continuous training in Germany. Working Paper National Bureau of Economic Research Inc., Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Rosen S 1972 Learning and Experience In the Labor Market. Journal of Human Resources 7(3): 326–42