View sample social influence and group dynamics research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The belief that we are the masters of our own destiny surely ranks among the most fundamental of human conceits. This overarching self-perception is viewed by many scholars as a prerequisite to personal adjustment, enabling us to face uncertainty with conviction and challenges with perseverance (cf. Alloy & Abramson, 1979; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Kofta, Weary, & Sedek, 1998; Seligman, 1975; Taylor & Brown, 1988), and as equally central to the maintenance of social order because of its direct link to the attribution of personal responsibility (cf. Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton, 1994; Shaver, 1985). Its adaptive significance notwithstanding, the sense that one’s actions are autonomous, self-generated, and largely impervious to external forces is routinely exaggerated in daily life (e.g., Langer, 1978; Taylor & Brown, 1988), and ultimately can be dismissed as philosophically untenable to the extent that it reflects naive assumptions about personal freedom (cf. Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Skinner, 1971). Social psychologists know better, and in their pursuit of the true causal underpinnings of behavior, they have routinely placed the individual at the intersection of various and sundry social forces. In this view, people represent interdependent elements that together comprise larger social entities, be they familial, romantic, or societal in nature. Against this backdrop, people continually influence and in turn are influenced by one another in myriad ways. Social influence is the currency of human interaction, and although its operation may be subtle and sometimes transparent to the individuals involved, its effects are pervasive.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In recognition of the primacy of influence in the social landscape, G. W. Allport (1968) defined the field of social psychology as “an attempt to understand . . . how the thought, feeling, and behavior of the individual are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others.” No other topic in social psychology can lay claim to such centrality. After all, no one has defined social psychology as the study of impression formation or self-concept, nor have researchers investigating such topics done so without assigning a prominent role to social influence processes. The belief in selfdetermination may well be important for personal and societal function, but the reality of social influence is equally significant—and for many of the same reasons. Our aim in this research paper is to outline the fundamental features of social influence and to illustrate the manifestations of influence in different contexts. In so doing, we emphasize the various functions served by social influence, both for the individual and for society.

Introduction

Because social influence is deeply embedded in every aspect of interpersonal functioning, any attempt to discuss it apart from all the topics and research traditions defining social psychology is necessarily incomplete and potentially misleading. How can one divorce a depiction of basic influence processes from such phenomena as attitude change, selfconcept malleability, or the development of close relationships? As it happens, of course, any field of scientific inquiry is differentiated into relatively self-contained regions, and social psychology is no exception. Although it can be argued that one person’s practical differentiation is another person’s unnecessary fragmentation (see, e.g., Gergen, 1985; Vallacher & Nowak, 1994), it is nonetheless the case that distinct theoretical and research traditions have emerged over the years to create a workable taxonomy of social psychological phenomena. Despite the pervasive nature of social influence, then, it is commonly treated as a separate topic in textbooks and secondary source summaries of relevant theory and research. To an extent, our treatment of social influence works within the accepted boundary conditions. Thus, we discuss such agreed-upon subtopics as compliance, conformity, and obedience to authority. At the same time, however, we attempt to impose a semblance of theoretical order on the broad assortment of relevant processes. So although each manifestation of influence—whether in advertising, the military, or intimate relationships—taps correspondingly distinct psychological mechanisms, there are certain invariant features that transcend the surface structure of social influence phenomena.

We begin by discussing the exercise of external control to influence people’s thoughts and behaviors. Rewards and punishments have self-evident efficacy in controlling behavior across the animal kingdom, so their incorporation into influence techniques in human affairs is hardly surprising. We then turn our attention to less blatant strategies of influence that typically fare better in inducing sustained changes in people’s thought and behavior. It is noteworthy in this regard that the lion’s share of the literature subsumed under the social influence label emphasizes subtle manipulation rather than direct attempts at control. We provide an overview of the principal manipulation techniques and abstract from them common features that are responsible for their relative success. This theme provides the foundation for an even less blatant approach to influence, one centering on the coordination of people’s internal states and overt behaviors. People have a natural tendency to bring their beliefs, preferences, and actions in line with those of the people around them, and this tendency becomes manifest in the absence of overt or subtle manipulation strategies. This penchant for interpersonal synchronization is what enables a mere collection of individuals to become a functional unit defining a higher level of social reality.

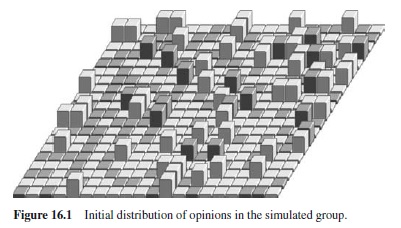

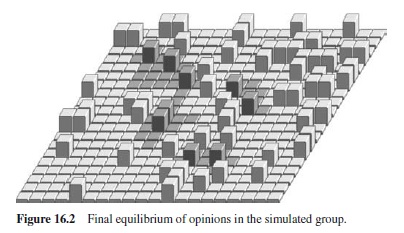

We then turn our attention to the manifestation of social influence at the level of society. A central theme here is that the emergence and maintenance of macrolevel properties in a social system can be understood in terms of the microlevel influence processes described in the preceding sections. We describe the results of computer simulations demonstrating this linkage between different levels of social reality. In a concluding section, we abstract what appear to be the common features of influence across different topics and relate them to fundamental psychological processes, chief among them the coordination of individual elements to create a coherent higher-order unit. Our suggestions in this regard are as much heuristic as integrative, and we offer suggestions for future lines of theoretical work to forward this agenda.

External Control

The most elemental way to influence someone’s behavior is make rewards and punishments contingent on the enactment of the behavior. For the better part of the twentieth century, experimental psychology was essentially defined in terms of this perspective, and during this era a wide variety of reinforcement principles were generated and validated. Attempts to extend these principles to social psychology were always complicated by the undeniable cognitive capacities of humans and the role of such capacities in regulating behavior (cf. Bandura, 1986; Zajonc, 1980). Nonetheless, several lines of research based on behaviorist assumptions are represented in social psychology (e.g., Byrne, 1971; Staats, 1975). With respect to social influence, this perspective suggests simply that people are motivated to do things that are associated with the attainment of pleasant consequences or the avoidance of unpleasant consequences. Thus, people adopt new attitudes, develop pBibliography: for one another, change the frequency of certain behaviors, or take on new activities because they in effect have been trained to do so. It’s fair to say this perspective never achieved mainstream status in social psychology, but one might think that social influence would be an exception. Reinforcement, after all, is defined in terms of the control of behavior, and to the extent that a self-interest premise underlies virtually all social psychological theories (cf. Miller, 1999), it is hard to imagine how the promise of reward or threat of punishment could fail to influence people’s thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Bases of Social Power

The ability to control someone’s behavior, whether by carrot or stick, is synonymous with having power over that person. Presumably, then, successful influence agents are those who are seen—by the target at least—as possessing social power. In contemporary society, power reflects more than physical strength, immense wealth, or the capacity and readiness to harm others—although having such attributes certainly wouldn’t hurt under some circumstances. Social power instead derives from a variety of different sources, each providing a correspondingly distinct form of behavior control. The work of French and Raven (1959; Raven, 1992, 1993) is commonly considered the definitive statement on the various bases of social power and their respective manifestations in everyday life. They identify six such bases: reward, coercion, expertise, information, referent power, and legitimate authority.

Reward power derives, as the term implies, from the ability to provide desired outcomes to someone. The rewards may be tangible and material (e.g., money, a nice gift), but often they are more subtle and nonmaterial in nature (e.g., approval, affection). The compliance-for-reward exchange may be direct and explicit, of course, as when a parent offers an economic incentive to a child for doing his or her homework. But the transaction is often tacit or implicit in the relationship rather than directly stated. The salesperson who pushes used cars with special zeal, for example, may do so because he or she knows the company gives raises to those who meet a certain sales quota. Coercive power derives from the ability to provide aversive or otherwise undesired outcomes to someone. As with rewards, coercion can revolve around tangible and concrete outcomes, such as the use or threat of physical force, or instead involve outcomes that are nonmaterial and acquire their valence by virtue of less tangible features. The parent concerned with a child’s study habits might express disapproval for the child’s shortcomings in this regard, for example, and the salesperson might redouble his or her efforts at moving stock for fear of losing his or her job.

Expert power is accorded those who are perceived to have superior knowledge or skills relevant to the target’s goals. Deference to such individuals is common when the target lacks direct personal knowledge regarding a topic or course of action. In the physician-patient relationship, for example, the patient typically complies with the physician’s instructions to take a certain medicine, even when the patient has no idea how the purported remedy will cure him or her. Knowledge, in other words, is power. Information power is related to expert power, except that it relates to the specific information conveyed by the source, not to the source’s expertise per se. Aperson could stumble on a piece of useful gossip, for example, and despite his or her general ignorance in virtually every aspect of his or her life, this person might wield considerable power for a time over those who would benefit from this information. Knowledge is power, it seems, even in the hands of someone who doesn’t know what he or she is talking about.

Referent power derives from people’s tendency to identify with someone they respect or otherwise admire. “Be like Mike” and “I am Tiger Woods,” for example, are successful advertising slogans that play on consumers’desire to be similar to a cultural icon. The hoped-for similarity in such cases, of course, is stunningly superficial—all the overpriced shoes in the world won’t enable a teenager to defy gravity while putting a basketball through a net or drive a small white ball 300 yards to the green in one stroke. Referent power is rarely asserted in the form of a direct request, operating instead through the pull of a desirable person, and can be manifest without the physical presence or surveillance of the influence agent. A young boy might shadow his older brother’s every move, for example, even if the brother hardly notices, and an aspiring writer might emulate Hemingway’s sparse writing style even though it is fair to say this earnest adulation is totally lost on Hemingway.

Legitimate power derives from societal norms that accord behavior control to individuals occupying certain roles. The flight attendant who instructs 300 passengers to put their tables in an upright position does not have a great deal of reward or coercive power, nor is he or she seen as necessarily possessing deep expertise pertaining to the request, and it is even more unlikely that he or she is the subject of identification fantasies for most of the passengers. Yet this person wields enormous influence over the passengers because of the legitimate authority he or she is accorded during the flight. Legitimate power is often quite limited in scope. A professor, for example, has the legitimate authority to schedule exams but not to tell students how to conduct their personal lives—unless, of course, he or she also has referent power for them. Legitimate power is clearly essential to societal coordination—imagine how traffic at a four-way intersection would fare if the signal lights failed and the police on the scene had to rely on gifts or their personal charisma to gain the cooperation of each driver. But blind obedience to those in positions of legitimate authority also has enormous potential for unleashing the worst in people, sometimes to the detriment of themselves or others. In recognition of this potential, social psychologists have devoted considerable attention to the nature of legitimate power, with special emphasis on obedience to authority. Not wanting to question this scholarly norm, we highlight this topic in the following section.

Obedience to Authority

Guards herding millions of innocent people into gas chambers, soldiers mowing down dozens of farmers and villagers with machine guns, and hundreds of cult members waiting in line for lethal Kool-Aid that is certain to kill themselves and their children: These images may be unthinkable, but they are part of the legacy of the twentieth century. Nestled in the security of our homes, we are nonetheless affected by such undeniable examples of mass abdications of personal responsibility and decision making; they can keep us up nights, not to mention undermine our sense of control. Although recent times have no monopoly on genocide, the abominations of World War II intensified the drive to plumb the depths of social influence, especially influence over the many by the few in the name of legitimate authority.

The best-known and most provocative line of research on this topic is that of Stanley Milgram (1965, 1974), who conducted a set of controversial laboratory experiments in the early 1960s. Milgram wanted to document the extent to which ordinary people will take orders from a legitimate authority figure when compliance with the orders entails another person’s suffering. The idea was to replicate in a relatively benign setting the dynamics at work during wartime, when soldiers are given orders to kill enemy soldiers and citizens. In his experimental situation, ostensibly concerned with the psychology of learning, participant “teachers” were asked to deliver electric shocks to “learners” (who were actually accomplices of Milgram) if the learners produced an incorrect response to an item on a simple learning task. In the initial study, Milgram (1965) found that 65% of the subjects cast in the teacher role obeyed the experimenter’s demand to proceed, ultimately administering 450 volts of electricity to a learner (a mild-mannered, middle-aged man with a selfdescribed heart condition) in an adjoining room, despite hearing the learner’s protests, screams, and pleas to stop emanating from the other room. Milgram subsequently performed several variations on this procedure, each designed to identify the factors responsible for the striking level of obedience initially observed. In one of the most intriguing variations, subjects were cast in the learner role as well as the teacher role, and the experimenter eventually told the teacher to cease administering shocks. Remarkably, some learners in this situation insisted that the teacher continue “teaching” them for the good of the experiment. Because the learner did not have the same degree of legitimacy as the experimenter did, however, none of the teachers acceded to the learner’s demand to continue shocking them.

Milgram’s findings proved unsettling to scholars and laypeople alike. With the horrors of World War II still fairly fresh in people’s memories, Milgram’s research suggested that Hitler’s final solution was not only fathomable, but perhaps also likely to occur again under the right circumstances. After all, these findings were produced by people from a nation of self-professed mavericks whose ancestors had risen up against the motherland’s authority less than two centuries earlier. Subsequent research employing Milgram’s basic paradigm has demonstrated comparable levels of obedience in many other countries, including Australia, Germany, Spain, and Jordan (Kilham & Mann, 1974; Meeus & Raaijmakers, 1986). The tendency to defer to legitimate authority, even when the demands of authority run counter to one’s personal beliefs and inhibitions, appears to be robust, representing perhaps an integral part of human nature.

The power of authority can derive from purely symbolic manifestations, such as titles or clothing, even when the ostensible authority has no credible claim to his or her role as a legitimate authority figure. A man wearing a security guard’s uniform, for example, can secure compliance with a request to pick up litter, even when the requests are made in a context outside the guard’s purview (Bickman, 1974). Even fictional symbols of authority can produce compliance. Television advertising trades on this tendency with astonishing commercial success. For example, the actor Robert Young, who played the part of Dr. Marcus Welby in a popular TV doctor series in the 1960s, wore a white lab coat in a commercial for Sanka (a brand of decaffeinated coffee). He was not an expert on coffee and certainly not a real doctor, yet the symbols of his authority (the white lab coat, the association with Dr. Welby) were sufficient to increase dramatically the sales of Sanka. Even when an actor states at the outset of a commercial pitch that I am not a doctor, but I play one on TV, his recommendations regarding cold remedies are followed by a significant portion of the viewing audience. This deference to titles and uniforms can have devastating effects. A study performed in a medical context, for example, found that 95% of nurses who received a phone call from a “doctor” agreed to administer a dangerous level of a drug to a patient (Hofling, Brotzman, Dalrymple, Graves, & Pierce, 1966).

Although pressures to obey authority are compelling, obedience is not inevitable. Research has shown, for example, that obedience to authority is tempered when the victim’s suffering is highly salient and when the authority figure is made to feel personally responsible for his or her actions (Taylor, Peplau, & Sears, 1997). Resistance to authority is enhanced, moreover, when the resister receives social support and in situations in which he or she is encouraged to question the motives, expertise, or judgments of the authority figure (Taylor et al., 1997). It should be reiterated, however, that legitimate authority serves important social functions and should not be viewed with a jaundiced eye only as a necessary evil in the human condition. Policeman, judges, elected representatives, and school crossing guards could not perform their duties if their power were not based on an aura of legitimacy. And as much as teachers like to be liked and to be seen as experts, their power over students in the classroom hinges to a large extent on students’perceiving them as legitimate authority figures. Even parents, who wield virtually every other kind of power (reward, coercion, expertise, information) over their children, must occasionally remind their offspring who is ultimately in charge in order to exact compliance from them. Obedience to authority, in sum, is pervasive in informal and formal social relations, and is neither intrinsically good nor intrinsically bad. Like many features of the human condition, its potential for good or evil is dependent on the restraint and judgment of those who exercise it.

Limitations of External Control

If the exercise of power always had its intended effect, both scholarly and lay interest in social influence would be minimal. Why bother obsessing over something as obvious as the tendency of people to defer to people in a position to offer rewards or threaten punishment? Is detailed experimentation really necessary to figure out why we listen to experts or model the behavior and attitudes of people we admire? And what could be more obvious than the observation that we typically comply with the demands and requests of those who are perceived as entitled to influence us in this way? Fortunately for social psychologists—and perhaps for intellectually curious laypeople as well—the story of social influence does not end with such self-evident conclusions, but rather unfolds with a far more interesting plotline. There is reason to think, in fact, that the general approach to influence outlined previously is among the least effective ways of implementing true change in people’s thoughts and feelings relevant to the behavior in question. Indeed, a fair portion of theoretical and research attention over the last 40 years has focused on the tendency for heavy-handed efforts at influence to boomerang, promoting effects opposite to those intended. This is especially the case for attempted influence that trades on reward and coercive power, although the assumptions underlying this line of theory and research would seem to hold true for legitimate power as well.

Psychological Reactance

To a certain extent, the failure of power-based approaches to induce change in people’s action pBibliography: can be traced to the fundamental human conceit noted at the outset. People want to feel like they are the directors of their own fate (cf. Deci & Ryan, 1985), and accordingly are sensitive to attempts by others to diminish this self-perceived role. No one really likes to be told what to do, and influence attempts that are seen in this light run the risk of producing resistance rather than compliance. Reactance theory (J. W. Brehm, 1966; S. S. Brehm & Brehm, 1981) trades on the assumption that people like to feel free, specifying how people react when this feeling is undermined. The basic idea is that when personal freedoms are threatened, people act to reassert their autonomy and control. Commanding a child not to do something runs the risk of eliciting an I won’t! rebuttal, for example, or reluctant compliance that disappears as soon as the surveillance is lifted (e.g., Aronson & Carlsmith, 1963). In effect, all the bases of power at the parent’s disposal—reward, coercion, referent, expert, legitimate—pale in comparison to the child’s distaste for having his or her tacit agreement removed from the parent-child exchange.

Considerable evidence has been accumulated over the years in support of the basic tenets of reactance theory (cf. Burger, 1992). Research by Burger and Cooper (1979), for example, found that even something as basic and spontaneous as humor appreciation is subject to reactance effects. Male and female college students were asked to rate ten cartoons in terms of funniness. Some participants rated the cartoons when alone, but others provided the ratings after receiving instructions from confederates to give the cartoons high ratings. Results revealed that pressure by the confederates tended to backfire, producing funniness ratings lower than those produced by participants not subject to the pressure. This effect was pronounced among individuals who had scored high on a preexperimental personality assessment of need for personal control.

Some studies have produced rather counterintuitive findings that call into question the basis for certain public policy initiatives. In a study investigating attempts to reduce alcohol consumption, for example, participants who received a strongly worded antidrinking message subsequently drank more than did those who received a moderately worded message (Bensley & Wu, 1991). The strongly worded message presumably was perceived by participants as a threat to their personal freedom, to which they reacted by drinking more rather than less in an effort to assert their sense of control. Findings such as these cast into doubt the wisdom of the Just say no mantra of many contemporary drug education programs aimed at young people. The slogan itself may promote the very behavior it is intended to discourage, because it represents a rather direct short-circuiting of targets’ personal decision-making machinery. There is evidence, in fact, that the Just say no approach has backfired in some instances, producing increased rather than decreased consumption of illegal substances—although it is not entirely clear that this effect is due primarily to reactance (Donaldson, Graham, Piccinin, & Hansen, 1995).

The experience of psychological reactance is not limited to influence techniques that trade on power per se. Indeed, the concernwithprotectingone’sself-perceivedfreedomcancurtail the effectiveness of any influence attempt that is seen as such.The use of flattery to seduce a target into a new course of action, for example, can backfire if the target is aware—or simply suspicious—that the flattery is being strategically employed for manipulative purposes (e.g., Jones & Wortman, 1973). Indeed, any attempt to gain influence over another person by becoming attractive to him or her runs a serious risk of failure if the attempted ingratiation is transparent to the person. Jones (1964) has referred to this stumbling block to interpersonal influence as the “ingratiator’s dilemma.” Normally, we like to hear compliments, to have others agree with our opinions, and to interact with people who are desirable by some criterion. As intrinsically rewarding as these experiences are, they also make us correspondingly vulnerable to requests and other forms of influence from the people in question. When their compliments become obsequious or if their desirability is buttressed by a little too much namedropping, we become suspicious that they are playing on this vulnerability with a particular agenda in mind. The result is resistance rather than assent to their subsequent requests, even requests that might otherwise seem quite reasonable.

Reactance, in short, is a pervasive human tendency that sets clear limits on the effectiveness of all manner of social influence. Power-based forms of influence are particularly vulnerable to reactance effects, not only because they are linked to a restriction of freedom for targets, but also because they tend to be explicit and thus transparent to targets. Letting someone know that you are trying to influence him or her is a decidedly poor strategy—unless, of course, your real goal is to get him or her to do the opposite.

Reverse Incentive Effects

Twentieth-century social psychology is a story of two seemingly incompatible perspectives on human nature. For the first half of the century, social psychology accepted as received wisdom the notion that the behavior of organisms, humans included, is ultimately under the control of external reinforcement. The mindless S-R models invoked by radical behaviorists may not have been most theorists’cup of tea, but no one seriously challenged the assumption that contingencies of positive and negative reinforcement play a pervasive role in shaping people’s psychological development as well as their specific behavior in different contexts. People’s concern over personal freedom was certainly recognized by social psychologists, but more often than not this penchant was considered an independent force that competed with reinforcement for the hearts and minds of people in their daily lives. Thus, people struggled to control their impulses, resist temptation, delay gratification, and maintain their dignity in the face of incentives to do otherwise.

After mid-century, something akin to a phase transition began to take place in social psychology. Fueled in large part by an emerging emphasis on the importance of cognitive mediation, theory and research began to question the imperial role of rewards and punishments in shaping personal and interpersonal behavior. People’s latent preoccupation with selfdetermination, for example, came to be seen not simply as a force that competed with reinforcement, but rather as a concern that was activated by explicit reinforcement contingencies (cf. de Charms, 1968; Deci & Ryan, 1985). Thus, the awareness of a contingency was said to sensitize people to the potential loss of self-determination if they were to adjust their behavior in accordance with the contingency. In effect, awareness of a contingent relation between behavior and reward weakened the power of the contingency, leaving the desire for self-determination the dominant casual force. This reasoning, of course, is consistent with the assumptions of reactance theory, described above. The dethroning of reinforcement theory, however, went far beyond a recognition of people’s need for autonomy, freedom, and the like. Two major perspectives in particular captured the academic spotlight for extended periods of time, and today they still stand as basic insights into human motivation—including motivation relevant to social influence.

The first of these, cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957), sparked psychologists’ imagination in large part because of its seemingly counterintuitive take on the role of rewards in shaping thought and behavior. The essence of the theory is a purported drive for consistency in people’s thoughts and feelings regarding a course of action. When inconsistency arises, it is experienced as aversive arousal, which motivates efforts to eliminate or at least reduce the inconsistency so as to reestablish affective equilibrium. This sounds straightforward enough, but under the right conditions a concern for restoring consistency can produce what can be described as reverse incentive effects (cf. Aronson, 1992; Wicklund & Brehm, 1976). In a prototypical experimental arrangement, subjects are induced to perform an action that they are unlikely to enjoy (e.g., a repetitive or boring task) or one that conflicts with an attitude they are likely to hold (e.g., writing an essay in support of raising tuition at their university). At this point, varying amounts of monetary incentive are offered for the action’s performance; some subjects are offered a quite reasonable sum (e.g., $20), others are offered a mere pittance (e.g., $1). Virtually all subjects agree to participate regardless of the incentive value, so technically they all perform a counterattitudinal task (i.e., a task that conflicts with their attitude concerning the task).

According to Festinger, the dissonance experienced as a result of such counterattitudinal behavior can be reduced by changing one of the cognitive elements to make it consistent with the other element. In this situation, the relevant cognitive elements for subjects presumably are their feelings about the action and their awareness they have performed the action. Because the latter thought cannot be changed (i.e., the damage is done), the only cognitive element open to revision is their attitude toward the action (which conveniently had not been assessed yet). So, the theory holds, subjects faced with this cognitive dilemma will adjust their attitude toward the action to make it consistent with the fact that they have engaged in the action. Subjects who performed a boring task now consider it interesting or important. Subjects who wrote an essay espousing an unpopular position now indicate they hold that position themselves. In effect, subjects rationalize their behavior by indicating that it really reflected their true feelings all along.

At this point, one might assume that all subjects would follow this scenario. But revising one’s attitude is not the only potential means of reducing the dissonance brought on by counterattitudinal behavior. Festinger suggested that a person can maintain his original attitude if he or she can justify the counterattitudinal behavior with other salient and reasonable cognitive elements. This is where the large versus small reward manipulation enters the picture. A subject offered a large incentive (e.g., $20) for performing the act can use that fact to justify what he or she has done. Who wouldn’t do something boring or even write an essay one doesn’t believe if the price were right? The reward, in other words, obviates the psychological need to change one’s feelings about what one has done. A subject offered a token incentive (e.g., $1), on the other hand, cannot plausibly argue that the reward justified engaging in the boring activity or writing the disingenuous essay. The only recourse in this situation is to revise one’s own attitude and indicate liking for the activity or belief in the essay’s position.

Note the upshot here: The smaller the contingent reward, the more positive one’s resultant attitude toward the behavior; or conversely, the larger the contingent reward, the more negative one’s attitude toward the rewarded behavior. This represents a rather stunning reversal of the conventional wisdom regarding the use of rewards to influence people’s behavior. To be sure, large rewards are useful—often necessary—to get a person to perform an otherwise undesirable activity or to express an unpopular attitude. But the effect is likely to be transitory, lasting only as long as the reward contingency is in place. To influence the person’s underlying thoughts and feelings regarding the action, and thereby bring about a lasting change in his or her behavioral orientation, it is best to employ the minimal amount of reward. In effect, lasting social influence requires reconstruction within the person rather than inducements from the outside.

Mental processes are notoriously hard to pin down objectively, of course, and this fact of experimental psychology has always been a problem for dissonance theory. Festinger and his colleagues did not attempt to measure what they assumed to be the salient cognitions at work in the reward paradigm, nor have subsequent researchers fared much better in providing definitive evidence regarding the stream of thought presumably underlying the experience and reduction of psychological tension. With this gaping empirical hole in the center of the theory, it is not surprising that other theorists soon rushed in to fill the gap with their own inferences about the true mental processes at work. In effect, the results observed in cognitive dissonance research served as something of a Rorschach for subsequent theorists, each of whom saw the same picture but imparted somewhat idiosyncratic interpretations of its meaning. Not all interpretations have fared well, however, and among those that have, there is sufficient common ground to characterize (in general terms at least) a viable alternative to the dissonance formulation.

Central to the alternative depiction of reverse incentive effects is the assumption that people’s minds are first and foremost interpretive devices, designed to impose coherence on the sometimes diverse and often ambiguous elements of personal experience. In analogy to Gestalt principles of perception, cognitive processes “go beyond the information given” (Bruner & Tagiuri, 1954) to impart higher-order meaning that links the information in a stable and viable structure. With respect to the dissonance paradigm, subjects’cognitive playing field is presumably populated with an abundance of salient or otherwise relevant information. These cognitive elements include the nature of the task (the activity or essay) and the money received, of course, but they no doubt encompass an assortment of other thoughts and feelings as well. Thus, subjects may be sensitized to their sense of personal freedom and control in that context, for example, or perhaps to their sense of personal competence in performing the task. For that matter, subjects might also be considering their feelings about the experimenter, pondering the value of the experiment, or rethinking the value of psychological research in general. In view of the plethora of likely cognitive elements and the potential for these elements to come in and out of focus in the stream of thought, the achievement of coherence is anything but a trivial task. What processes are at work to impart coherence to this complex and dynamic array of information? And what psychological dimensions capture the resultant coherence?

There is hardly a shortage of relevant theories. Several early models, for example, emphasized processes of causal attribution (cf. Bem, 1972; Jones & Davis, 1965; Kelley, 1967) that were said to promote personal interpretations favoring either internal causation (e.g., personal beliefs and desires) or external causation (most notably, the monetary incentive). In this view, a large incentive provides a reasonable and sufficient cause for engaging in the activity, shortcircuiting the need to make inferences about the causal role of one’s beliefs or desires. A small incentive, on the other hand, is not perceived as a credible cause for taking the time and expending the effort to engage in the activity, so one instead invokes relevant beliefs and desires as causal forces for the behavior. In effect, the counterintuitive influence of rewards is a testament to their perceived efficacy in causing people to do things they might not otherwise do. Causal attribution, of course, is not the only plausible endpoint of coherence concerns. Other well-documented dimensions relevant to higher-order integrative understanding include evaluative consistency (cf. Abelson et al., 1968), explanatory coherence (cf. Thagard & Kunda, 1998), narrative structure (cf. Hastie, Penrod, & Pennington, 1983), and level of action identification (cf. Vallacher & Wegner, 1987). It is hardly surprising, then, that a number of other models have been fashioned and tested in an attempt to explain why rewards sometimes fail to influence people’s beliefs and desires in the intended direction (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Kruglanski, 1975; Harackiewicz, Abrahams, & Wageman, 1987; Trope, 1986; Vallacher, 1993).

Taken together, the various models emphasizing inference and interpretation have a noteworthy advantage over the standard dissonance reduction model in that they predict reverse incentive effects for any action, not just those that are likely to be viewed in a context-free manner as aversive by some criterion (e.g., repetitive, boring, pointless, timeconsuming, etc.). Indeed, some of the most interesting research has established conditions under which otherwise enjoyable or interesting activities can seemingly lose their intrinsic interest by virtue of their association with material rewards (cf. Lepper & Greene, 1978). Rewards do not always have this effect, however, a point that has been incorporated with varying degrees of success into many of these models. Still, the theoretical preoccupation with the effects of rewards has generated an unequivocal lesson: The success or failure of attempted influence depends on how the attempt engages the mental machinery of the target. Rewards can be perceived as bribery and aversive consequences can mobilize resistance, for example, and both can activate concerns about one’s freedom of action and self-determination. Social influence does not operate on blank minds, but rather encounters an active set of interpretative processes that operate according to their own dynamics to make sense of incoming information (Vallacher, Nowak, Markus, & Strauss, 1998).

Manipulation

Change in people’s behavior can be imposed from the outside by the exercise of power, but this approach to influence may prove effective only as long as the relevant contingencies (reward, punishment, expertise, information) are in place. To influence people in a more fundamental sense, it is necessary to include them as accomplices in the process. Aself-sustaining change in behavior requires a resetting of the person’s internal state—her or her beliefs, preferences, goals, and so on—in a way that preserves the person’s sense of freedom and control. Assuming the influence agent has an agenda that does not coincide with the target’s initial pBibliography: and concerns, the agent may then find it necessary to employ subtle strategies designed to manipulate the relevant internal states of the target. Couched in these terms, social influence boils down to various means by which an agent can obtain voluntary compliance from targets in response to his or her requests, offers, or other forms of overture. Research has identified several compliance-inducing strategies, some of which rely on basic interpersonal dynamics, others of which reflect the operation of basic social norms. We discuss specific manifestations of these general approaches in the following sections.

Manipulation Through Affinity

Could you pass the broccoli? Will you marry me? Whether the agenda at issue is mundane or life-altering, requests provide the primary medium by which people seek compliance from one another. Requests are a fairly routine feature of everyday social interaction and have been examined for their effectiveness under experimental arrangements designed to identify basic principles. However, requests are also central to businesses, charitable organizations, political parties, and other societal entities that depend on contributions of money, effort, or time from the citizenry. Accordingly, much of the knowledge concerning compliance has been gleaned from observation—sometimes participant observation—of professional influence agents operating in charitable, commercial, or political contexts (cf. Cialdini, 2001). Experimentation and real-world observation provide cross-validation for one another, and together have generated a useful taxonomy of effective strategies for obtaining compliance. Many of these strategies are based on what can be called the affinity principle—the tendency to be more compliant in the hands of an influence agent we like as opposed to dislike.

The Affinity Principle

Whoever suggested caution in the face of friends bearing gifts may not have been advocating cynicism, but rather selfpreservation. Extensive research supports the commonsense notion that personal affinity motivates compliance. From sales professionals, the consummate chameleons of the commercial world, to con artists preying on the elderly and college students calling home for cash, several effective influence strategies rest on the influence agent’s being liked, known by, or similar to the target. When such affinity exists between agent and target, ruse is not necessarily a prerequisite for compliance. Quite the opposite, in fact, can be true.

Consider, for example, the Tupperware Corporation, which has exploited the power of friendship in an unprecedented fashion. It has been reported that a Tupperware party occurs somewhere every 2.7 seconds (Cialdini, 1995)— although they typically last much longer than that, which suggests the sobering possibility that there is never a moment without one. The format is as follows: A host invites friends and relatives over to his or her home to participate in a gathering at which Tupperware products are demonstrated by a company representative. Armed with the knowledge that their friend and host will receive a percentage of sales, the attendees tend to buy willingly, because they are purchasing from someone they know and like rather than from a stranger. As confirmation for the pivotal role of “liking” in this context, Frenzen and Davis (1990) found that 67% of the variance in purchase likelihood was accounted for by socials ties between the hostess and the guest and only 33% by product preference.

Personal affinity has been shown to be a potent compliance inducer even in the absence of the liked individual. Anecdotal evidence of this phenomenon abounds in our daily lives. It is the rare parent who has not sent his or her child around to friends and neighbors to collect for a school walkathon or raffle. The child, hardly the embodiment of a “compliance professional” (Cialdini, 2001), represents the parent who is (one would hope) liked by the target. In the same vein, Cialdini (1993) discovered that door-to-door salespersons commonly ask customers for names of friends upon whom they might call. Although we may wonder what kind of friends a person might surrender in this way, rejecting the salesperson under these circumstances apparently is seen as a rejection of the referring friend—the person for whom affinity is felt. The potency of the affinity principle per se may be diminished by the physical absence of the liked person, but the allusion appears nonetheless to render the target more susceptible to other compliance tactics.

The affinity principle is not limited to influence seekers and their surrogates, but applies as well to those who are known or at least recognized by the target. During elections, for example, voters have been shown to cast their ballots for candidates with familiar-sounding names (Grush, 1980; Grush, McKeough, & Ahlering, 1978). In similar fashion, survey response rates sometimes double if the sender’s name is phonetically similar to the recipient’s (Garner, 1999). Physical attractiveness represents another extension of the affinity principle. A total stranger blessed with good looks has a distinct advantage over his or her less attractive counterparts in securing behavioral compliance (Benson, Karabenick, & Lerner, 1976) and attitude change (Chaiken, 1979). Good grooming, for example, accounts for greater variance in hiring decisions than does the applicant’s job qualifications, although interviewers deny the impact of attractiveness (Mack & Rainey, 1990). In political campaigns, meanwhile, there is evidence that a candidate’s attractiveness can substantially influence voters’ perceptions of him or her and affect their voting behavior as well (Budesheim & DePaola, 1994; Efran & Patterson, 1976). Even criminal justice is not immune to the power of physical attractiveness. Better-looking defendants generally receive more favorable treatment in the criminal justice system (Castellow, Wuensch, & Moore, 1990) and often receive lighter sentences when found guilty (Stewart, 1980).

Similarity and Affinity

Similarity between influence agent and target represents a special case of the affinity principle. It is rarely a coincidence when a car salesperson claims to hail from a customer’s home state or when an apparel salesperson claims to have purchased the very same outfit the vacillating customer is sporting. People like those who are similar to them (cf. Byrne, 1971; Byrne, Clore, & Smeaton, 1980; Newcomb, 1961), and in accordance with the affinity principle, they are inclined to respond affirmatively to requests from similar others as well. The similarity effect encompasses a wide range of dimensions, including opinions, background, lifestyle, and personality traits (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Even similarity in nonverbal cues, such as posture, mood, and verbal style, has been observed to increase compliance (LaFrance, 1985; Locke & Horowitz, 1990; Woodside & Davenport, 1974). The effect of similarity is quite pervasive, having been demonstrated across a wide range of variation in age, cultural background, socioeconomic status, opinion topics, and relationship types (cf. Baron & Byrne, 1994).

The power of similarity to elicit compliance has been observed even when the dimension of similarity is decidedly superficial in nature. Sometimes outward manifestations of similarity such as clothing are all that are required. Emswiller, Deaux, and Willits (1971), for example, arranged for confederates to dress as either “straight” or “hippie” and had them ask fellow college students for a dime to make a phone call.When the confederate and target subject were similar in their respective attire, compliance was observed over two thirds of the time. When the confederate-target pair differed in clothing type, however, less than half of the students volunteered the dime. In a related vein, Suedfeld, Bochner, and Matas (1971) observed that if antiwar protestors were asked by a similarly dressed confederate to sign a petition, they tended to do so without even reading the petition. Automatic compliance to the requests of others perceived to be similar has a decidedly nonthinking quality to it. The very automaticity of the similarity principle, however, may have important adaptive significance. By using this heuristic to make quick decisions regarding compliance requests, people can allocate their valuable but limited mental resources to other types of judgment and decision-making situations defined in terms of ambiguous, conflicting, or complex information.

Esteem and Affinity

Perhaps even more basic than our propensity to do things for those we like is our need to be liked by those we know (cf. G. W. Allport, 1939; Baumeister, 1982; Tesser, 1988). To be sure, for some people the desire to be liked can be overridden by other motives, such as the need for acceptance (Rudich & Vallacher, 1999) or desires to be seen accurately (Trope, 1986) or in accordance with one’s personal self-view (Swann, 1990). For most people most of the time, however, it is hard to resist the allure of flattery. Receiving positive feedback from someone is highly rewarding and tends to promote a reciprocal exchange with the source. In other words, we like others who seem to like us. When activated in this way, the affinity principle makes the recipient of flattery a potential target for influence by the flatterer.

Flattery has a long history as an effective compliance technique, both inside and outside the laboratory (cf. Carnegie, 1936/1981; Cialdini, 2001). Drachman, DeCarufel, and Insko (1978), for example, arranged for men to receive positive or negative comments from a person in need of a favor. The person offering praise alone was liked most, even if the targets knew that the flatterer stood to gain from their liking them. Moreover, inaccurate compliments were just as effective as accurate compliments in promoting the target’s affinity for the flatterer. So influence agents need not bother gathering facts to support their complimentary onslaught; simply expressing positive comments may be sufficient to woo the target and thereby gain his or her compliance.At the same time, however, the ingratiator’s dilemma (Jones, 1964) discussed earlier sets limits on the effectiveness of the esteem principle. In particular, praise and other forms of ingratiation (e.g., opinion conformity with the target) can backfire if the ingratiator’s ulterior motives are readily transparent and the praise is seen as solely manipulative. And, of course, the influence agent can simply overdo the flattery and come across as disingenuous and obsequious.

Manipulation Through Scarcity

From childhood on, we want what we lack—be it toys, money, fancy cars, or greener grass. The cache of the unattainable, for example, is a sure bet to spark competition and fuel sales in commercial settings. Cries of today and today only and in limited quantities have been known to drive shoppers like lemmings toward the blue-light special, and convenient Christmastime shortages of Tickle Me Elmos or Furbees stoke the fires of demand for such toys. We may see ourselves as impervious to such base tactics, but the power of the human tendency to view scarcity as an indicator of worth or desirability is undeniable, well-documented— and routinely exploited as a method of securing compliance (cf. Cialdini, 2001).

It’s interesting in this regard to consider the tendency for efforts at censorship to backfire, creating a stronger demand than ever for the forbidden fruit. The prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s, for example, only whetted people’s appetite for liquor and spawned the rise of secret establishments (the speakeasy) that provided access to the scarce commodity. Antipornography crusades typically have the same effect, increasing interest in the banned books and magazines, even among people who might not otherwise consider this particular genre. Telling people they cannot read or see something can increase—or even create—a desire to take a proverbial peek at the hard-to-find commodity. By the same token, after the censorship or prohibition is lifted, interest in the object in question tends to wane.

Surprisingly, there is a paucity of research on the psychology of scarcity. The enhanced desirability of scarce items may reflect a perceived loss of freedom to attain the items, in line with reactance theory. The censorship example certainly suggests that people value an object in proportion to the injunction against having it. People don’t like having their freedom threatened, and making an item difficult to obtain or forbidding an activity clearly restricts people’s options with respect to the item and the activity. Reactance is a reasonable model, but one can envision other theoretical contenders. Simple supply-and-demand economics, for example, has a direct connection to the scarcity phenomenon. The lower the supply-demand ratio with respect to almost any item, the more those who control the resource can jack up the price and still count on willing customers. Perhaps there are viable evolutionary reasons for the heightened interest in scarce resources. The conditions under which we evolved were harsh and uncertain, after all, and there may have been selection pressures favoring our hominid ancestors who were successful at securing and hording valuable but limited food supplies and other resources.

Yet another possibility centers on people’s simultaneous desires to belong and to individuate themselves from the groups to which they belong (e.g., Brewer, 1991). Scarcity has a way of focusing collective attention on a particular object, and there may be a sense of social connectedness in sharing the fascination with others. Waiting in line with throngs of shoppers hoping to secure one of the limited copies of the latest Harry Potter volume, for example, is arguably an annoying and irrational experience, but it does make the person feel as though he or she is on the same wavelength as people who would otherwise be considered total strangers. At the same time, if the person is one of the lucky few who manages to secure a copy before the shelves are cleared, he or she has effectively individuated him- or herself from the masses. In essence, influence appeals based on scarcity may be effective because they provide a way for people to belong to and yet stand out from the crowd in a world where he or she may routinely feel both alienated and homogenized.

Manipulation Through Norms

Human behavior, compliance included, is driven to a large extent by social norms—context-dependent standards of behavior that exert psychological pressure toward conformity. At the group level, norms provide continuity, stability, and coordination of behavior among individuals. At the individual level, norms provide a moral compass for deciding how to behave in situations that might offer a number of action alternatives. The norm of social responsibility (e.g., Berkowitz & Daniels, 1964), for example, compels us to help those less fortunate than ourselves, and the norm of equity prevents us from claiming excessive compensation for minimal contribution to a group task (cf. Berkowitz & Walster, 1976). Norms pervade social life, and thus provide raw material for social influence agents. By tapping into agreed-upon and internalized rules for behavior, those who are so inclined can extract costly commitments to behavior from prospective targets without having to flatter them.

The Norm of Reciprocity

The obligation to repay what others provide us appears to be a universal and defining feature of social life. All human societies subscribe to the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), which is understandable in light of the norm’s adaptive value (Axelrod, 1984). The sense of future obligation engendered by this norm promotes and maintains both personal and formal relationships. And when widely embraced by people as a shared standard, the reciprocity norm lends predictability, interpersonal trust, and stability to the larger social system. Transactions involving tangible assets are only a subset of the social interactions regulated by reciprocity. Favors and invitations are returned, Christmas cards are sent to those who send them, and compliments are rarely accepted without finding something nice to say in return (Cialdini, 2001).

The social obligation that there be a give for every take is well-documented (DePaulo, Brittingham, & Kaiser, 1983; Eisenberger, Cotterell, & Marvel, 1987; Regan, 1971). Even when gifts and favors are unsolicited (or unwanted), the recipient feels compelled to provide something in return. The ability of uninvited gifts to produce feelings of obligation in the recipient is successfully exploited by many organizations, both charitable and commercial. People may not need personalized address labels, key rings, or hackneyed Christmas cards, but after they have been received, it is difficult not to respond to the organization’s request for a “modest contribution” (e.g., Berry & Kanouse, 1987; Smolowe, 1990). A particularly vivid example of this tendency is provided by the Hare Krishna Society (Cialdini, 2001). The members of this religious sect found that they could dramatically increase the success of their solicitations in airports simply by giving travelers a free flower before asking for donations. People find it hard to turn down a request for money after receiving an unsolicited gift, even something as irrelevant to one’s current needs as a flower. That receiving a flower is not exactly the high point of the recipients’ day is confirmed by Cialdini’s observation that the flower more often than not winds up in a nearby waste container shortly after the flower-for-money transaction has been completed.

Reciprocity can have the subsidiary effect of increasing the recipient’s liking for the gift- or favor-giver, but the norm can be exploited successfully without implicit application of the affinity principle (e.g., Regan, 1971). Affect does enter the picture, however, when people fail to uphold the norm. Nonreciprocation runs the risk of damaging an exchange relationship (Cotterell, Eisenberger, & Speicher, 1992; Meleshko & Alden, 1993) and may promote reputational damage for the offender (e.g., moocher, ingrate) that can haunt him or her in future transactions. Somewhat more surprising is evidence that negative feelings can be engendered when the reciprocity norm is violated in the reverse direction. One might think that someone who provides a gift but does not allow the recipient to repay would be viewed as generous, unselfish, or altruistic (although perhaps somewhat misguided or naive). But under some circumstances, such a person is disliked for his or her violation of exchange etiquette (Gergen, Ellsworth, Maslach, & Seipel, 1975). This tendency appears to be universal, having been demonstrated in U.S., Swedish, and Japanese samples.

Cooperation is an interesting manifestation of the reciprocity norm. Just as the act of providing a gift or a favor prompts repayment, cooperative behavior tends to elicit cooperation in return (Braver, 1975; Cialdini, Green, & Rusch, 1992; Rosenbaum, 1980) and can promote compliance with subsequent requests as well (Bettencourt, Brewer, Croak, & Miller, 1992). This notion is not lost on the car salesperson who declares that he or she and the customer are on “the same side” during price negotiations, and then appears to take up the customer’s fight against their common enemy, the sales manager. Even if this newly formed alliance comes up short and the demonized sales manager purportedly holds fast on the car’s price, the customer may feel sufficiently obligated to repay the salesperson’s cooperative overture with a purchase.

A related form of reciprocity is the tactical use of concessions to extract compliance from those who might otherwise be resistant to influence. The strategy is to make a request that is certain to meet with a resounding no, if not a rhetorical are you kidding? The request might call for a large investment of time and energy, or perhaps for a substantial amount of money. After this request is turned down, the influence agent follows up with a more reasonable request. In effect, the influence agent is making a concession and, in line with the reciprocity norm, the target now feels obligated to make a concession of his or her own. Astudy by Cialdini et al. (1975) illustrates the effectiveness of what has come to be known as the door-in-the-face technique. Posing as representatives of a youth counseling program, Cialdini et al. approached college students to see if they would agree to chaperon a group of juvenile delinquents for several hours at the local zoo. Not surprisingly, most of them (83%) refused. The results were quite different, though, if Cialdini et al. had first asked the students to do something even more unreasonable—spending 2 hours per week as counselors to juvenile delinquents for a minimum of 2 years. After students refused this request—all of them did—the smaller zoo-trip request was agreed to by 50% of the students, a tripling of the compliance rate. The empirical evidence for the door-in-the face technique is impressive (cf. Cialdini & Trost, 1998) and largely supports the reciprocity of concessions interpretation.

The power of reciprocal concessions is also apparent in the that’s not all technique, which is a familiar trick of the trade among salespeople (Cialdini, 2001). The tactic involves making an offer or providing a come-on to a customer, then following up with an even better offer before the target has had time to respond to the initial offer. This technique is used fairly routinely to push big-ticket commercial items. A salesperson, for example, quotes a price for a large-screen TV, and while the interested but skeptical couple is thinking it over, he or she adds, “but that’s not all—if you buy today, I’m authorized to throw in a free VCR.” Research confirms that the effectiveness of the that’s not all technique is indeed attributable in part to the creation of a felt need in the target to reciprocate the agent’s apparent concession (e.g., Burger, 1986), although the contrast between the initial and follow-up concession plays a role as well. In the real world, the knowledge that people tend to reciprocate concessions provides a cornerstone of negotiation and dispute resolution. The bargaining necessary to reach a compromise solution in such instances invariably hinges on one party’s making a concession with the assumption that the other party will follow suit with a concession of his or her own. This phenomenon can be seen at work in a wide variety of contexts, including business, politics, international diplomacy, and marriage.

Reciprocity in Personal Relationships

The norm of reciprocity is not limited to transactions between people who otherwise would have little to do with one another (e.g., salespeople and consumers), but rather provides a foundation for virtually every kind of social relationship. The reciprocity norm even plays a role in personal relationships, serving to calibrate the fairness in people’s ongoing interactions with friends and lovers. The trust and warmth necessary to maintain a personal relationship would be impossible to maintain if either partner felt that his or her overtures of affection, self-disclosures, offers of assistance, and birthday gifts went unreciprocated (cf. Lerner & Mikula, 1994). There are two complications here, however. First, the partners to a relationship are not always equally invested in or dependent on the relationship (e.g., Rusbult & Martz, 1995). In terms of social exchange theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959), the comparison level for alternatives (CLalt) for each partner may be substantially different, and this differential dependency can promote exploitative behavior by the less dependent person. In effect, the person who feels more confident that he or she could establish desirable alternative relationships (i.e., the person with the higher CLalt) can set the terms of exchange in the relationship. This power asymmetry need not be discussed explicitly in order for it to promote inequality in overt expressions of affection, the allocation of duties and responsibilities, and decision making.

The second complication arises in relationships that achieve a certain threshold of closeness. Intimate partners are somewhat loathe to think about their union in economic, titfor-tat terms, preferring instead to emphasize the communal aspect of their relationship (cf. M. S. Clark & Mills, 1979). They feel they operate on the basis of need rather than equity or reciprocity, and this perspective enables them to make sacrifices for one another without expecting compensation or repayment. The apparent suspension of reciprocity may be more apparent than real, however. The issue is not reciprocity per se, but rather the time scale on which reciprocity and other exchange metrics are calculated. What looks like selfless and unrequited sacrifice by one person in the short run can be viewed as inputs that are eventually compensated by the other person in one form or another (cf. Foa & Foa, 1974). Depending on the sacrifice (e.g., fixing dinner vs. taking on a second job), the time scale for repayment can vary considerably (e.g., hours or days vs. weeks or even years), but at some point the scales need to be balanced. The sense that one has been treated unfairly or exploited—or simply that one’s assistance and affection have not been duly reciprocated—can ultimately spoil a relationship and bring about its dissolution.

Commitment

Although it is not usually listed as a social norm, commitment can influence behavior as much as do reciprocity, equity, responsibility, and other basic social rules and expectations (Kiesler, 1971). After people have committed themselves to an opinion or course of action, it is difficult for them to change their minds, recant, or otherwise fail to stay the course. Commitment does not derive its power solely from the anger and disappointment that breaking of a commitment would engender in others—although this certainly counts for something—but also from a basic desire to act consistently with one’s point of view. A commitment that is expressed publicly, whether in front of a crowd or to a single individual, is especially effective in locking in a person’s opinion or promise, making it resistant to change despite the availability of good reasons for reconsideration (cf. Deutsch & Gerard, 1955; Schlenker, 1980).

Agents of influence play on this seemingly noble tendency, often for decidedly nonnoble purposes of their own. Several specific techniques have been observed in real-world settings and confirmed in research (Cialdini & Trost, 1998). Perhaps the best-known tactic is referred to as the foot-in-thedoor, which is essentially the mirror image of the door-in-theface tactic. Rather than starting out with a large request and then appearing to make a concession by making a smaller request, the foot-in-the-door specialist begins with a minor request that is unlikely to meet with resistance. After securing committing with this request, the influence agent ups the ante by making a far more costly request that is consistent with the initial request. Because of commitment concerns, it can be very difficult at this point for the target to refuse compliance. A series of clever field experiments (Freedman & Fraser, 1966) provide compelling evidence for the effectiveness of this tactic. In one study, suburban housewives were contacted and asked to do something that most of them (78%) refused to do: allow a team of six men from a consumer group to come into their respective homes for 2 hours to “enumerate and classify all the household products you have.” Another group of housewives was contacted and presented with a much less inconvenience-producing request— simply answering a few questions about their household soaps (e.g., “What brand of soap do you use in your kitchen sink?”). Nearly everyone complied with this minor request. These women were contacted again three days later, but this time with the larger home-visit request. In this case, over half the women (52%) complied with the request and allowed the men to rummage through their closets and cupboards for 2 hours.

The commitment process underlying this tactic goes beyond the target’s concern with maintaining consistency with the action per se. It also engages the target’s self-concept with respect to the values made salient by the action. Thus, the women who complied with the initial request in the Freedman and Fraser (1966) studies were presumably sensitized to their self-image as helpful, public-spirited individuals.To maintain consistency with this suddenly salient (and perhaps newly enhanced) self-image, they felt compelled to comply with the later, more invasive request.Assuming this to be the case, the foot-in-the-door tactic holds potential for influencing people’s thought and behavior long after the tactic has run its course. Freedman and Fraser (1966) themselves noted a parallel between their approach and the approach employed by the Chinese military on U.S. prisoners of war captured during the Korean War in the early 1950s. A prisoner, approached individually, might be asked to indicate his agreement with mild statements like The United States is not perfect.After the prisoner agreed with such minor anti-American statements, he might be asked by the interrogator to elaborate a little on why the United States is not perfect. This, in turn, might be followed by a request to make a list of the “problems with America” he had identified, which he was expected to sign. The Chinese might then incorporate the prisoner’s statement in an anti-American broadcast. As a consequence of this ratcheting up of an initially mild anti-American statement, a number of prisoners came to label themselves as collaborators and to act in ways that were consistent with this selfimage (cf. Schein, 1956).

Commitment underlies a related tactic known as throwing a lowball, which is routinely employed by salespeople to gain the upper hand over customers in price negotiations (Cialdini, 2001).Automobile salespeople, for example, will seduce customers into deciding on a particular car by offering it at a very attractive price. To enhance the customer’s commitment to the car, the salesperson might allow the customer to arrange for bank financing or even take the car home overnight. But just before the final papers are signed, something happens that requires changing the price or other terms of the deal. Perhaps the finance department has caught a calculation error or the sales manager has disallowed the deal because the company would lose money at that price. At this point, one might think that the customer would back out of the deal— after all, he or she has made a commitment to a particular exchange, not simply to a car. Many customers do not back out, however, but rather accept the new terms and proceed with the purchase. Apparently, in making the initial commitment, the customer takes mental possession of the object and is reluctant to let it go (Burger & Petty, 1981; Cioffi & Garner, 1996).

Changing the terms of the deal without undermining the target’s commitment is not limited to shady business practices. Indeed, lowball tactics underlie transactions having nothing to do with economics, and can be used to gain people’s cooperation to do things that center on prosocial concerns rather than personal self-interest (e.g., Pallak, Cook, & Sullivan, 1980). In an interesting application of the lowball approach, Cialdini, Cacioppo, Bassett, and Miller (1978) played on college students’potential commitment to psychological research. Students in Introductory Psychology were contacted to see if they would agree to participate in a study on “thinking processes” that began at 7:00 a.m. Because this would entail waking up before the crack of dawn, few students (24%) expressed willingness to participate in the study. For another group of students, however, the investigators threw a lowball by not mentioning the 7:00 a.m. element until after the students had indicated their willingness to take part in the study. Amajority of the students (56%) did in fact agree to participate, and none of them backed out of this commitment when informed of the starting time. After an individual has committed to a course of action, new details associated with the action—even aversive details that entail unanticipated sacrifice—can be added without undermining the psychological foundations of the commitment.

Like the lowball tactic, the bait-and-switch tactic works by first seducing people with an attractive offer. But whereas the lowball approach changes the rules by which the exchange can be completed, the bait-and-switch tactic nixes the exchange altogether, with the expectation that the target will accept an alternative that is more advantageous to the influence agent. Car salespeople once again unwittingly have furthered the cause of psychological science by their shrewd application of this technique (Cialdini, 2001). They get the customer to the showroom by advertising a car at a special low price. Taking the time to visit the showroom constitutes a tentative commitment to purchase a car. Upon arrival, the customer learns that the advertised special is sold, or that because of its low price, the car doesn’t come with all the features the customer wants. Because of his or her commitment to purchase a car, however, the customer typically expresses willingness to examine and purchase a more expensive model—even though he or she wouldn’t have made the trip to look at these models in the first place.

Social Coordination

To this point, social influence has been described as if it were a one-way street. One person (the influence agent) has an agenda that he or she wishes to impose upon another person (the influence target). Although influence strategies certainly are employed for purposes of control and manipulation, social influence broadly defined serves far loftier functions in everyday life. Indeed, as noted at the outset, it is hard to discuss any aspect of social relations without acceding a prominent role to influence processes. Social influence is what enables individuals to coordinate their opinions, moods, evaluations, and behaviors at all levels of social reality, from dyads to social groups to societies. The process of social coordination is a thus a two-way street, with all parties to the exchange influencing and receiving influence from one another. The ways and means of coordination are discussed in this section, as are the functions—both adaptive and maladaptive—of this fundamental human tendency.

Conformity

People go to a lot trouble to influence one another. Yet for all the effort expended in service of manipulation, sometimes all it takes to influence a person is to convey one’s own attitude or action preference. People take solace from the expressions of like-minded people and develop new ways of interpreting reality from those with different perspectives. In both cases, simply expressing an opinion—no tricks, strategies, or power plays—may be sufficient to bring someone into line with one’s point of view. This form of influence captures the essence of conformity, a phenomenon that is commonly counted as evidence for people’s herdlike mentality. There is a nonreflective quality to many instances of conformity, but this property enables people to coordinate their thoughts in an efficient manner and attain the social consensus necessary to engage in collective action. We consider first what constitutes conformity, and then we develop both the positive and negative consequences of this manifestation of social influence.

Group Pressure and Conformity

Conformity represents a “change in behavior or belief toward a group as a result of real or imagined group pressure” (Kiesler & Kiesler, 1976). Defined in this way, conformity would seem to be a defining feature of group dynamics. Festinger (1950), for example, suggested that pressures toward uniformity invariably exist in groups and are brought to bear on the individual so that over time, he or she will tend to conform to the opinions and behavior patterns of the other group members. If one of two diners at a table for two says that he or she finds the food distasteful and the other person expresses a more favorable opinion, the first person is unlikely to change his or her views to match those of his or her companion. However, the addition of several more dinner companions, each holding the contrary position, may well cause the person to rethink his or her position and establish common ground with the others. If he or she has yet to express an opinion, the likelihood of conforming to the others’opinions is all the greater. To investigate the variables at work in this sort of context—group size, unanimity of group opinion, and the timing of the person’s expressed judgment—Solomon Asch (1951, 1956) performed a series of experiments that became viewed unanimously by social psychologists as classics.