Sample Cognitive Therapy Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

1. Definition

Cognitive therapy is one of a large number of psychotherapy approaches that was developed in the latter part of the twentieth century. It is associated principally with its originator, Dr. Aaron Beck. The treatment model falls within a broader class of treatments, which are referred to as the cognitive- behavioral therapies (Dobson, 2001). The cognitive-behavioral therapies share certain theoretical underpinnings, notably: (a) that cognitive events affect behavior (the mediational hypothesis); (b) that cognitive events can be assessed and systematically modified (the accessibility hypothesis); and (c) that cognitive change can be employed to cause therapeutic changes in behavior or adaptive functioning. In this regard, cognitive therapy is similar to other schools of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, such as rational-emotive psychotherapy.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Cognitive therapy distinguishes itself from other cognitive-behavioral therapies by the particular organization of its theoretical constructs. The model proposes that the manner in which an individual views, appraises, or perceives events around himself herself is what dictates their subsequent emotional responses and behavioral choices. Although the con-tent of situation-specific appraisals will vary as a function of the person’s activities, the model also posits that these appraisals may be accurate or distorted, positive or negative. For example, an individual reacts to what another individual said in an interpersonal interaction, as well as to what he or she thinks about those statements.

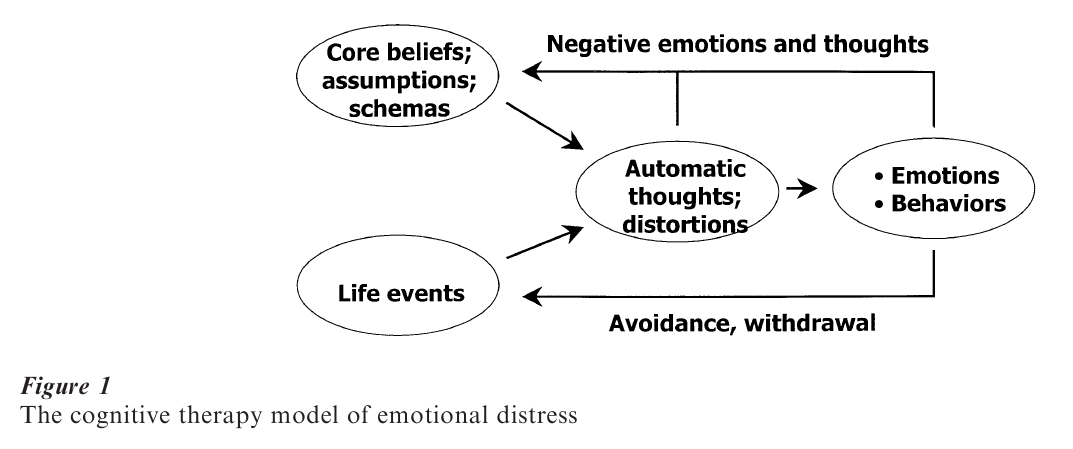

The extent to which the individual sees situations accurately, or conversely may be distorting, is in part a function of the individual’s core beliefs (also referred to as underlying assumptions, or schemas). These core beliefs are hypothesized to be intrapsychic phenomena that emerge over the person’s lifetime, based on their experiences. Once established, these beliefs not only increase the likelihood of certain cognitive reactions to life events, but also then influence proactively the way in which an individual chooses to spend their time, career, partner choices, etc., which also tend to reinforce these beliefs. Thus, over time cognitive beliefs become the basic factor in what may become an increasingly negative and closed feedback loop (see Fig. 1).

Cognitive therapy is a systematic treatment, which is founded on the cognitive model of distress. The principal emphases in therapy are assisting the patient to identify, evaluate, and modify the potentially faulty information processing they engage in, as well as the underlying beliefs or schemas that drive that information processing. This process typically begins with an assessment of adaptive functioning and behavioral patterns that might either enhance or interfere with the process of treatment. In the case of depression, the patient may be encouraged to increase their activities to alleviate negative mood, and to ensure that the patient is at least engaged in their life sufficiently to generate negative information processing that can then be the focus of treatment. In the case of marital distress, negative interactional patterns (e.g., fighting, spousal abuse) will be assessed and modified before interventions aimed at relationship beliefs will be attempted.

Once the patient is able to engage in a review of their negative thinking, a number of methods can be employed to assess this thinking. Strategies include counts of particular thoughts, questioning in the therapy session, thoughts about imagined situations, or the use of a written thought record (J. Beck 1995). Dependent on the pattern of dysfunctional thinking that is identified, various therapeutic techniques can be employed to change these patterns. For example, if a patient recurrently believes they ‘cannot’ be assertive with certain people, the therapist and patient can collaborate to set up circumstances in which they can test this idea empirically. In doing so, adaptive thinking and various behavioral competencies can be enhanced.

At a certain stage of treatment, it is typically the case that a patient’s situation-specific automatic thoughts are accurate and adaptive, and that they are functioning more adaptively than when they first arrived for treatment. At this stage of treatment, the focus will move to the more general beliefs that prompted the patient’s problems in the first instance. This work includes a search for the common themes underlying specific thoughts. These themes can take the form of beliefs about how ‘the world’ operates, or schemas that have developed about the self. Techniques that can be used include inductive questioning, a review of the negative thinking patterns seen by the therapist and patient, examination of historical pat-terns of thought and behavior, and a review of life events related to the problem. Once identified, dysfunctional beliefs can be challenged systematically through behavioral experiments, bibliotherapy, open discussion with key people in the patient’s life, and other ‘assumptive techniques’ (J. Beck 1995).

In summary, cognitive therapy is a systematic and progressive form of treatment that typically includes assessment and modification of adaptive functioning, situation-specific automatic thinking, and more en-grained, long-term beliefs and self-schemas. The cognitive content of various forms of disorders is increasingly understood, and it includes themes of danger in anxiety (Beck and Emery 1985), loss in depression (Beck et al. 1979, Clark et al. 1999), and transgression in anger (Beck 1999). Further, the cognitive processes associated with various disorders (e.g., magnification of perceived danger in anxiety) are also increasingly understood.

2. Intellectual Context

Beck’s original interest was in understanding and treating depression. He began his departure from his original psychoanalytic training through a series of studies of the dreams and daytime thoughts of de-pressed patients, in which he discovered that the content of these thoughts had stereotypical content. Further, he hypothesized that these depressed patients engaged in negative distortions of their world in order to obtain these thoughts. Based on these observations, he developed a treatment in which the negative cognitions were systematically tested, in order to undermine cognitive distortions and the negative thinking seen in depression (Beck et al. 1979).

The early formulation of cognitive therapy was put to its first empirical test in an outcome study in the late 1970s. Based on a developed treatment manual, cognitive therapy was contrasted with antidepressant medication. This study revealed that cognitive therapy had equal outcome to medication in the short term and superior outcome at follow-up. As a consequence of the original success of cognitive therapy, a number of outcome studies were conducted in the area of depression in subsequent years.

The first meta-analysis of these studies (Dobson 1989) used a standard outcome measure, the Beck Depression Inventory, and compared cognitive therapy to other forms of treatment. This analysis revealed that cognitive therapy patients ended treatment 0.5 standard deviations less depressed than patients receiving other treatments. Further, compared to wait list or placebo conditions, the effect size for cognitive therapy indicated that it was over 2 standard deviations superior to no treatment. Although the results of the above meta-analysis were criticized due to questions about the selection process for including studies, the conclusion that cognitive therapy is at least equal to pharmacotherapy has not been challenged seriously. Further, a more recent meta-analysis (Gloaguen et al. 1998) has confirmed the results found earlier by Dobson (1989).

More specifically, Gloaguen et al. (1998) found similar effect sizes to the earlier analysis, although the overall magnitude of these effects was somewhat attenuated. Notably, in an examination of long-term effects, it was also reported that relapse rates from cognitive therapy were approximately one-half of those observed for drug therapy for depression. Most recently, DeRubeis et al. (1999) conducted a ‘mega-analysis’ of treatment for depression, in which they collapsed the data from four outcome studies and analyzed the effects of cognitive therapy for depression, relative to drug therapy. They concluded that these two forms of therapy were equally effective, even for severely depressed patients. As such, it is an established fact that cognitive therapy is an effective treatment for clinical depression.

Notwithstanding the demonstrated efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression, a number of questions continue to require theoretical and empirical attention. The model underlying cognitive therapy states that cognitive distortions and situation-specific negative thoughts emerge from an interaction between core beliefs (also referred to as cognitive schemas, or underlying assumptions) and the life events that impinge on these beliefs. Once the core beliefs are activated and negative cognitions are produced, the emotional and behavioral consequences of these thoughts naturally flow (see Fig. 1). This mediational model, while intuitive and having lead to a successful treatment technology, has yet to be validated through research. In fact, based on a comprehensive examination of the research that has tested the various assumptions of cognitive therapy (Clark et al. 1999), the conclusion is that cognitive mediation remains to be proven.

Another challenge for the cognitive therapy of depression model comes from a component analysis of this treatment. Jacobson et al. (1996) conducted a randomized clinical trial in which depressed patients received either only the behavioral interventions associated with cognitive therapy, behavioral interventions and those aimed at situation-specific distortions, or the complete cognitive therapy program. Contrary to predictions, all three treatment conditions had equal outcomes, both in the short term and at up to two years follow-up. This study suggests that the cognitive interventions that are the hallmark features of the treatment may not, in fact, contribute to outcome more than the behavioral components of the treatment. If replicated, these results suggest that the active ingredients of cognitive therapy should be reconceptualized.

Further issues exist with regard to cognitive therapy of depression. These include the role of patient characteristics that potentially effect treatment out-come, the role of life stress in depression, the recent focus on schema-focused cognitive therapy (Clark et al. 1999), the risk of relapse relative to other treat-ments, and assessment issues relative to the adherence and competence of therapists in providing cognitive therapy.

3. Changes In Focus Or Emphasis Over Time

Branching out from the early work on depression (Beck et al. 1979), Beck and his colleagues extended the cognitive model to other clinical conditions. Beck and Emery published a treatment manual for anxiety disorders in 1985, which was followed by works dedicated to marital disorder (Beck 1988), personality disorders (Beck et al. 1990), substance use and abuse (Beck et al. 1993), and—most recently—anger and aggression (Beck 1999). Other works on cognitive therapy have appeared for bipolar disorder, as well as numerous chapters in various sources (see J. Beck 1995 for a review).

Throughout the development of cognitive therapy, some features have remained constant. First, while the content of cognition related to various forms of disorders necessarily varies, there has been a consistent emphasis on the process of thinking in cognitive therapy that permits many of the treatment techniques to be applied across disorders. For example, a common intervention in cognitive therapy is assessing the reality basis, or veridicality, of certain perceptions. This intervention can be used successfully in many forms of anxiety disorders, depression, marital distress, and anger-related problems.

A second consistent emphasis in cognitive therapy has been a focus on treatment efficacy. From the outset of the development of cognitive therapy, Beck and colleagues have maintained that efficacy studies are required to establish the clinical utility of cognitive therapy. No doubt it is in part due to this emphasis that many of the psychological treatments now being recognized as empirically supported are variants of cognitive therapy.

4. Methodological Issues Or Problems

Two primary sets of methodological issues have constrained the development of cognitive therapy. The first of these is related to the methodological issues inherent in clinical research. The randomized clinical trial methodology, which has become the standard in the development of psychotherapy, makes a number of requirements on investigators. These include the need for a well-defined independent variable, which in the context of psychotherapy means a treatment manual. Unfortunately, a consequence of this requirement is that fully developed treatment manuals are often developed before the research that is needed to substantiate them has been conducted. A second requirement of clinical trials is that the subject group be clearly specified. In psychotherapy research, this requirement has often been translated into using diagnostically related groups, ideally with few or no complicating co-morbid conditions. The relative homogeneity of research participants, while providing a good test of the intervention, unfortunately leads to what may be relatively poor generalizability of re-search findings. The requisite training for research trials has also been controversial. A fourth area of controversy surrounds the measurement and evaluation of outcome. Typically, the outcomes of a given treatment can be assessed in a number of ways (diagnostically, at the symptom level, or using specialized assessment tools), and the analysis of the out-comes can also be handled in several ways. As a consequence of these various strategies to conduct clinical trials, the scientific status of various treatments can be challenged. Given that most psychological treatments are developed in universities with publicly funded grants, and further given the necessarily limited set of questions that any one treatment study can address, it is not surprising that considerable efficacy and effectiveness research in the area of cognitive therapy is needed.

The second major methodological issue for cognitive therapy is the measurement of mechanisms of change. The cognitive model of distress makes a series of assumptions about the nature of cognitive processes involved in the development and treatment of various disorders (see Fig. 1). The measurement of cognition has been a difficult task, however—particularly as some of the constructs in the model are hypothetically latent until activated (Ingram et al. 1998). Even in the area of depression, where the greatest concentration of work has taken place to assess these constructs, some of the hypothesized mechanisms of change have yet to be established (Clark et al. 1999, Ingram et al. 1998). Research from the level of both theory and therapy are required to further evaluate the relationship between cognitive change and other parameters of clinical change in cognitive therapy.

5. Probable Future Directions Of Theory And Research

Despite the success of cognitive therapy, and its phenomenal growth over the past two decades, there is no doubt that considerable development remains (Dobson and Khatri 2000). Some of the directions for this work that have been identified in the literature include:

(a) A need for continued emphasis on efficacy research, particularly as cognitive therapy is applied to new and innovative areas.

(b) A need for effectiveness research that assesses such issues as the utility of cognitive therapy relative to other treatments, the clinical acceptability of treatment to patients, and other issues that affect how practical the treatment is to apply in varied clinical contexts.

(c) Continued work on the measurement of cognition (Ingram et al. 1998) and the mechanisms of change in cognitive therapy is clearly warranted. Cognitive therapy is a complex, multi-component treatment, the mechanisms of which are only be-ginning to be studied. The results of this research will contribute both to the theory and application of the treatment.

(d) Theoretical therapy development and efficacy work are needed to address the issue of whether cognitive therapy is an exhaustive theory that can integrate other models (Dobson and Khatri, 2000), or whether it might be integrated optimally into other treatment models.

(e) There is a need for research that assesses the success and failure of cognitive therapy for patients of diverse backgrounds. This ‘aptitude by treatment’ research will help the theory of cognitive therapy to develop, as well as to ensure the most appropriate treatment is provided to different patient populations. (f) Predicated on the assumption that cognitive therapy continues to enjoy strong clinical outcomes and popularity in the treatment community, further research is needed to understand the optimal method to disseminate this treatment approach. Tied to this development are issues related to how to best measure therapist adherence and competence in cognitive therapy.

Bibliography:

- Beck A T 1988 Love is Never Enough. Harper and Row, New York

- Beck A T 1999 Prisoners of Hate: The Cognitive Bases of Anger, Hostility and Violence. Harper Collins, New York

- Beck A T, Emery G 1985 Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. Basic Books, New York

- Beck A T, Freeman A et al. 1990 Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. Guilford Press, New York

- Beck A T, Rush A J, Shaw B F, Emery G 1979 Cognitive Therapy of Depression. Guilford Press, New York

- Beck A T, Wright F D, Newman C, Liese B S 1993 Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse. Guilford Press, New York

- Beck J 1995 Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. Guilford Press, New York

- Clark D A, Beck A, Alford B A 1999 Cognitive Theory and Therapy of Depression. Wiley, New York

- DeRubeis R J, Gelfand L A, Tang T Z, Simons A D 1999 Medications vs. cognitive behavioral therapy for severely depressed outpatients: A mega-analysis of four randomized comparisons. The American Journal of Psychiatry 156: 1007–13

- Dobson K S 1989 A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 57: 414–9

- Dobson K S (ed.) 2001 Handbook of Cognitive-behavioral Therapies, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

- Dobson K S, Khatri N 2000 Cognitive therapy: Looking backward, looking forward. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56: 907–23

- Gloaguen V, Cottraux J, Cucherat M, Blackburn I 1998 A meta-analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy in depressed patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 49: 59–72

- Ingram R, Miranda J, Segal Z V 1998 Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression. Guilford Press, New York

- Jacobson N S, Dobson K S, Truax P, Addis M, Koerner K, Gollan J, Gortner E, Prince S 1996 A component analysis of cognitive behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64: 295–304