View sample Empirically Supported Psychological Treatments Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Changes in the US healthcare system, set in full motion during the past decade and continuing to evolve, are likely to have a profound impact on the way psychotherapy is practiced. Two primary forces are driving the changes: (a) the increasing penetration of managed care and other types of cost-conscious medical plans, and (b) the development and proliferation of clinical practice guidelines. The most notable impact of these trends has been the requirement for greater accountability on behalf of service providers. Essentially, managed care and practice guidelines ask the question: does a treatment work and, if so, is it cost effective? Although these forces are influencing every area of healthcare, the current paper will discuss their specific impact on the practice of psychotherapy, and explore why the identification, promotion, and dissemination of empirically supported treatments (ESTs; i.e., those with controlled research data supporting their efficacy, see below for the specific criteria used to make this determination) is essential to the survival of psychological interventions as a firstline treatment for emotional disorders.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Managed Care

More than any previous event, managed care organizations (or any other system monitoring the utilization and cost of service such as health maintenance organizations, capitated contracts with providers, etc.) are reshaping the practice of psychotherapy. In the traditional fee-for-service model, decisions about the cost and length of treatment were primarily a function of choices made by the doctor and patient. The allocation of resources (i.e., cost of psychotherapy) was of little concern to the clinician. In fact, the fee-for-service model encourages the provision of service, as more service creates more income. However, in response to the increased costs of psychotherapy, and in particular to the perceived ‘endless’ nature of psychotherapy, managed care organizations are pressuring clinicians to allocate decreasing (less than usual) amounts of service.

While to date, the focus of managed care organizations cost cutting has been almost entirely on limiting the number of sessions a patient receives, ultimately, in order to compete, managed care organizations will have to focus on the quality and efficacy of the psychotherapeutic interventions as well. Managed care organizations are clearly motivated to cut costs. However, they must also satisfy the consumer (i.e., patient), and payor (e.g., employer providing health benefits) and therefore have to balance cost cutting with patient outcome. Simply reducing the length of care will not accomplish this goal, because many, and perhaps the majority, of psychotherapists are trained in ‘long-term’ therapeutic interventions which by nature require more sessions than managed care organizations are willing to allocate. Simply reducing the length of therapies devised to take place over a longer period of time is likely to result in ineffective outcomes, leading both to consumer dissatisfaction and increased costs down the road as the severity of the disorder may increase, becoming less responsive to treatment. Thus, concern for the effectiveness of an intervention will eventually temper the managed care organizations focus on economics. Ultimately, managed care organizations will be interested in clinicians providing the ‘optimal intervention … the least extensive, intensive, intrusive and costly intervention capable of successfully addressing the presenting problem’ (Bennett 1992, p. 203).

2. Practice Guidelines

A second force that will have a significant impact on the practice of psychotherapy is the establishment of clinical practice guidelines and treatment consensus statements. As noted by Smith and Hamilton (1994), ‘Guidelines are now being developed because there is a perception that inappropriate medical care is sometimes provided and that such inappropriate care has both health and economic consequences’ (p. 42). It is well known that in all medical fields there is significant variability in treatments delivered to patients with various illnesses. Patients are not necessarily receiving the most effective treatment. Consequently, in order to ensure that patients uniformly receive the optimal intervention—whether it be a type of medication, surgical procedure, or psychotherapeutic intervention—clinical practice guidelines are being developed. For the most part, the development of practice guidelines relies on systematically evaluating scientific and clinical input.

One organization developing practice guidelines is the federal Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHCPR). In order to create impeccable guidelines, only treatments with documented efficacy from randomized controlled trials are considered. Therefore, for an intervention to be included as a first-line treatment, research evidence attesting to its efficacy must be available. Without this evidence, one cannot conclude if a treatment is effective or ineffective, or make judgments about its relative efficacy compared with other available treatments.

The recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines are quite clear. Consider the wording from the AHCPR guideline for Depression (Depression Guideline Panel 1993). When psychotherapy is going to be selected as the sole treatment, the guideline states ‘Psychotherapy should generally be time-limited, focused on current problems, and aimed at symptom resolution rather than personality change as the initial target. Since it has not been established that all forms of psychotherapy are equally effective in major depressive disorder, if one is chosen as the sole treatment, it should have been studied in randomized controlled trials’ (Depression Guideline Panel 1993, p. 84). In addition to endorsing specific treatments for depression that had sufficient empirical evidence (e.g., cognitive, behavioral, interpersonal), the report goes on to state ‘Long-term therapies are not currently indicated as first-line acute phase treatments’ (p. 84).

Along the same line as treatment guidelines, consensus statements are likely to carry a significant amount of weight in determining what treatments have been shown to be effective as well. For example, in 1991 a Consensus Development Conference on the Treatment of Panic Disorder was held, sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. As was true in the process of developing the AHCPR treatment guidelines, the merit of various treatments was determined by the available scientific evidence. The format of the conference was to let ‘each camp put its best data forward’ and the panelists would evaluate and weigh the evidence to formulate a consensus statement (Wolfe and Maser 1994). As in the case of treatment guidelines, specific treatments were judged to be effective for panic disorder: Several pharmacological compounds and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (cf. Panic Consensus Statement published in Wolfe and Maser 1994). Once again, as is true of treatment guidelines, the wording of the Panic Consensus Statement as to the use of treatments not supported by empirical evidence, whether they be psychological or pharmacological, is quite clear, ‘One risk of maintaining individuals in nonvalidated treatments of panic disorder is that misplaced confidence in the therapy’s potential effectiveness may preclude application of more effective treatment.’ The statement spells out a specific concern about the use of psychotherapies without demonstrated effectiveness for panic disorder, ‘The nature of the therapeutic relationship makes it difficult for the patient to seek additional or alternate treatment.’

As one can imagine, as clinical guidelines and treatment consensus statements continue to emerge for a wide array of emotional disorders, they will have a significant impact on the way clinicians practice psychotherapy. In effect, these documents set standards of care, which if ignored, leave the clinician both ethically and legally vulnerable. Health insurance companies and managed care plans are now providing their practitioners with copies of guidelines and asking that they be followed. The implications are clear: failure to provide an empirically supported treatment from these guidelines, when one exists, may constitute malpractice in the eyes of the payor. For example, a number of states have passed, or are in the process of passing, legislation that give guidelines the ‘force of law’ by protecting clinicians who follow the guidelines from malpractice litigation (Barlow and Barlow 1995).

3. Identifying, Promoting, And Disseminating Empirically Supported Treatments

Recognizing the lack of utilization of ESTs and considering the trends noted above, the Society of Clinical Psychology (Division 12 of the American Psychological Association) established a task force to identify, promote, and assist in the dissemination of ESTs. The original Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures (now named the Committee on Science and Practice; CSP) was created by David H. Barlow, then president of the Society. The CSP is now a standing committee in the Society of Clinical Psychology, and the work will continue into the future (the most up-to-date reports and a list of committee members are available on the Internet at www.apa.org/divisions/div12).

As noted in a recent paper summarizing the accomplishments and future directions of the CSP (Weisz et al. 2000), there are two broad goals guiding the CSP: to influence both practice and science. Ideally, the influence on practice would be to improve mental health care for the public by encouraging and supporting empirically supported practice and by fostering clinical training that emphasizes reliance on ESTs. As for science, the CSP hopes to stimulate improvement of the quality and clinical utility of treatment research so that it is most relevant to the concerns of clinicians (see Weisz et al. 2000 for specific details).

3.1 Identifying Empirically Supported Treatments

The first mission of the original Task Force was to define criteria to determine whether treatments qualified as ESTs. The following criteria were established (Chambless et al. 1998). For treatments to be considered by the Task Force, research must have been conducted with treatment manuals. This requirement was set because treatment manuals make for better research design, and the use of a treatment manual allows readers to know what specific procedures have been supported. For example, although many interventions fall under the rubric of behavior therapy (e.g., exposure, relaxation training, cognitive restructuring), only exposure and response prevention has been demonstrated as efficacious for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Stating that behavior therapy is effective for obsessive-compulsive disorder does not allow the reader to know what specific strategies were tested and how they were applied. Use of a treatment manual solves this dilemma.

As for whether or not the treatment qualifies as an EST, the Task Force distinguishes between two levels of EST ‘well-established’ and ‘probably-efficacious.’ EST status is determined by the results from group design and single-case design studies. With regard to group design studies, to qualify as a well-established treatment, at least two studies conducted by different investigators must qualify as supporting studies. The following criteria must be satisfied in order to qualify as a supporting study: (a1) treatment is superior to pill placebo or psychological placebo, or (a2) treatment is equivalent to an already established treatment; (b) a treatment manual was used in the study; (c) characteristics of the client sample must be clearly specified. A treatment may not meet criteria for well-established but still satisfy the less conservative criteria for a probably efficacious treatment: two studies show that the treatment is more effective than a waiting list control group, or only one supporting study exists, or if more than one exists, all were conducted by the same investigator. (For details concerning the definition of EST, including use of single subject designs, and resolution of conflicting data, the reader is directed to the Task Force report itself.)

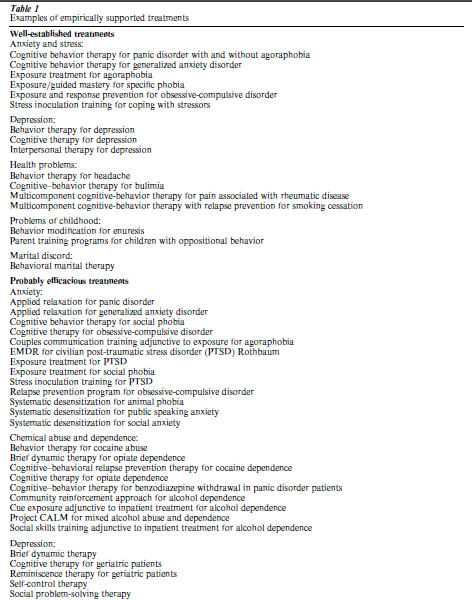

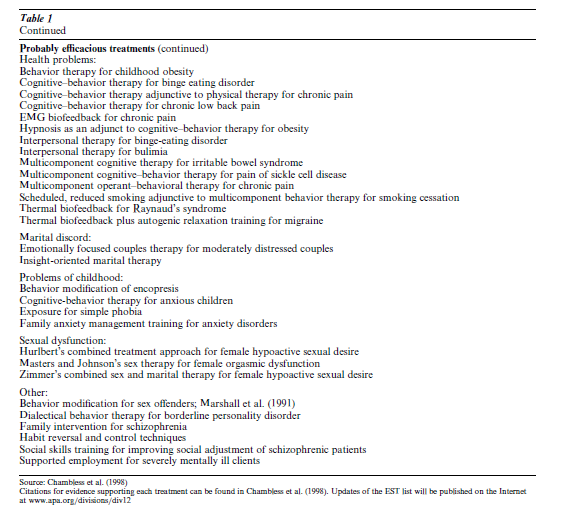

Based upon these criteria, a list of ESTs was published in 1995 (Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures 1995) and two subsequent updates have appeared (Chambless et al. 1996, 1998). As can be seen in Table 1, the Task Force has identified more than 70 ESTs (Chambless et al. 1998). It is important to note that it is not assumed that treatments without empirical evidence supporting them are ineffective, but instead, in the absence of scientific data, no conclusion can be drawn about its efficacy or lack thereof.

4. Promotion And Dissemination

Deciding upon criteria and identifying ESTs is only the first step in the process towards increasing their utilization so that the general public benefits. The second step is to call attention to ESTs so that practitioners, health insurers, and the general public is aware of their efficacy (promotion), and to be sure that practitioners are able to use these treatments (dissemination).

4.1 Promotion

As noted by Barlow (1994), despite the considerable data that exist demonstrating the efficacy of psychological interventions, they seem to be taking a backseat to pharmacological approaches in clinical practice guidelines. Why? Perhaps one reason is that, unlike pharmaceutical companies that spend a significant amount of money promoting the use of their treatments to consumers and providers, no such profit motivated organization exists for psychotherapeutic interventions. As a result, many patients are not aware that effective psychological treatments exist, and thus, do not seek them out. Clearly, more effort needs to be focused educating the public about ESTs. As a first step towards this goal, the CSP is about to launch a website listing a description of ESTs for a range of disorders so that ‘consumers’ of mental health services can find out what types of treatments have been shown to be effective for the problem disorder for which they are seeking treatment.

4.2 Dissemination

Identifying and promoting ESTs will not solve all the problems noted above. The next step is to ensure that the treatments are available. Unfortunately, as suspected by the CSP, a recent survey of clinical psychology doctoral programs and internship programs revealed that there is insufficient training in ESTs (Crits-Christoph et al. 1995). For example, as noted above, the two of the first-line treatments for depression listed by the AHCPR Depression Treatment Guideline were cognitive therapy and interpersonal therapy. The survey by Crits-Christoph et al. (1995) revealed that among clinical psychology internship programs—the place where clinical psychologists receive the bulk of supervised clinical experience—only 59 percent of programs provided supervision in cognitive therapy for depression, and a mere 8 percent of programs provided supervision in interpersonal psychotherapy. These are two psychotherapeutic treatments listed as first-line interventions for depression in the AHCPR Depression Treatment Guideline, thus, the lack of training in these areas is of significant concern. University doctoral programs were slightly better; 80 percent providing supervision in cognitive therapy and 16 percent in interpersonal psychotherapy. It is important to note, however, that having supervision available does not require students to receive it. As a result, these numbers do not indicate that 80 percent of students are in fact receiving training in cognitive therapy, and thus, the percentages are an overestimation of the number of students receiving supervision in that approach. For example, only 14 percent of internship programs required training in cognitive therapy for depression and only 3 percent in interpersonal therapy. Unfortunately, training in ESTs for depression is the highest. As noted in the Crits-Christoph et al. (1995) survey, only a handful of programs require training in a range of ESTs. For example, the survey revealed that only 7 percent of internship sites provide supervision in interpersonal therapy (IPT) for bulimia, 5 percent in CBT for social phobia. The numbers for doctoral programs, though higher, are still not all that promising: 21 percent offer supervision in IPT for bulimia, 24 percent in CBT for social phobia. Each of these treatments represents a first-line intervention for the respective disorder (with some of the treatments being the only empirically supported psychotherapeutic intervention), so it is not as though training in other EST approaches is occurring. Unfortunately, training in other ESTs is similar to the low numbers for depression, bulimia, and social phobia.

If training at the graduate and internship level is lacking, one can imagine how difficult it will be to disseminate these treatments to practitioners already practicing in the field. To date, no formal process exists to disseminate and train ESTs to practitioners. A perfect example of the consequence of this is that despite the strong data supporting cognitive behavioral treatment for panic disorder, a recent survey found that the majority of patients with panic disorder receiving psychological treatment receive dynamic psychotherapy (which has not been empirically supported as a first-line treatment) (Goisman et al. 1999). Indeed, as noted by Calhoun et al. (1998) in a recent paper discussing training in ESTs, reaching professionals out in the field is the most problematic area. With a rapidly changing data base, clinicians trained 10 years ago are unlikely to be up-to-date with the newer, empirically supported psychotherapies. Indeed, the majority of references supporting ESTs have appeared in the past 10 years (Calhoun et al. 1998). How can clinicians become motivated to learn ESTs? Even if they are motivated, how can treatments be disseminated in a way to provide high integrity supervision to insure they are properly trained? The CSP plans to devote a considerable amount of effort to develop a model that would facilitate training professionals in ESTs, because as discussed above, this is an essential activity for the survival of psychotherapy as a viable first-line treatment for emotional disorders. For those interested, a list of manuals outlining ESTs is available (cf. Sanderson and Woody 1995; available at www.apa.org/divisions/div12).

5. Criticism Of The EST Movement

The movement towards ESTs are not welcomed by everyone within our profession, and indeed, several authors have raised important concerns and criticisms (e.g., Garfield 1998, Kovacs 1995, Nathan 1998) regarding the identification of ‘validated’ therapies. Although space does not permit a discussion of the specific issues here, in fact, the CSP agrees that there are difficulties and risks in establishing so-called psychotherapy guidelines—or any treatment guidelines for that matter (cf. Pincus 1994 concerning the development of psychiatry guidelines)—yet the CSP and other professional organizations believe the benefits clearly outweigh the risks (Pincus 1994, Sanderson 1995), and thus, will continue the work outline above (cf. Weisz et al. 2000 for a discussion of the future directions of the CSP).

Bibliography:

- American Psychiatric Association 1993 Practice guidelines for major depressive disorder in adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 150(4): 1–26 (Suppl. 5.)

- Barlow D H 1994 Psychological interventions in the era of managed care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 1: 109–22

- Barlow D H, Barlow D G 1995 Guidelines and empirically validated treatments: Ships passing in the night? Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 4: 25–9

- Bennett M J 1992 The managed care setting as a framework for clinical practice. In: Feldman J L, Fitzpatrick R J (eds.) Managed Mental Healthcare: Administrative and Clinical Issues. American Psychiatric Press, Washington, DC, pp. 203–18

- Calhoun K S, Moras K, Pilkonis P A, Rehm L P 1998 Empirically supported treatments: Implications for training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66: 151–62

- Chambless D L, Sanderson W C, Shoham V, Johnson S B, Pope K, Crits-Christoph P, Baker M, Johnson B, Woody S R, Sue S, Beutler L, Williams D, McCurry S 1996 Empirically validated therapies: A project of the division of clinical psychology, American psychological association, task force on psychological interventions. The Clinical Psychologist 49: 5–15

- Chambless D L, Baker M J, Baucom D, Beutler L E, Calhoun K S, Crits-Christoph P, Daiuto A, DeRubeis R, Detweiler J, Haaga D A F, Johnson S B, McCurry S, Mueser K T, Pope K S, Sanderson W C, Shoham V, Stickle T, Williams D A,

- Woody S R 1998 Update on empirically validated therapies: II. The Clinical Psychologist 51: 3–16

- Crits-Christoph P, Frank E, Chambless D L, Brody C, Karp J F 1995 Training in empirically validated therapies: What are clinical psychology students learning? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26: 514–22

- Depression Guideline Panel 1993 Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Clinical Practice Guideline, Number 5. Rockville, MD (Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research. AHCPR Publication No. 93- 0551). US Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

- Garfield S 1998 Some comments on empirically supported treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66: 121–5

- Goisman R, Warshaw M, Keller M B 1999 Psychosocial treatment prescriptions for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry 156: 1819–21

- Kovacs A 1995 We have met the enemy and he is us! The Independent Practitioner 15(3): 135–7

- Nathan P E 1998 Practice guidelines: not yet ideal. American Psychologist 53: 290–9

- Pincus H A 1994 Treatment guidelines: Risks are outweighed by the benefits. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 4: 40–45

- Sanderson W C 1995 Can psychological interventions meet the new demands of health care? American Journal of Managed Care 1: 93–8

- Sanderson W C, Woody S 1995 Manuals for empirically validated treatments. A project of the division of clinical psychology, American psychological association, task force on psychological interventions. The Clinical Psychologist 48: 7–11

- Smith G R, Hamilton G E 1994 Treatment guidelines: Provider involvement is critical. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 4: 40–45

- Task force on promotion and dissemination of psychological procedures 1995 Training in and dissemination of empiricallyvalidated psychological treatments. The Clinical Psychologist 48: 3–23

- Weisz J R, Hawley K M, Pilkonis P A, Woody S R, Follette W C 2000 Stressing the other three Rs in search of empiricallysupported treatments: Review procedures, research quality, relevance to practice and public interest. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7: 243–58

- Wolfe B E, Maser J D (eds.) 1994 Treatment of Panic Disorder: A Consensus Statement. American Psychiatric Association Press, Washington, DC