View sample environmental psychology research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Why Psychology Needs Environmental Psychology

Introduction

This research paper looks to the past, present, and future of environmental psychology. The paper begins with a discussion of the importance of the socioenvironmental context for human behavior. Having demonstrated that the environment, far from being a silent witness to human actions, is an integral part of the plot, the paper continues with an examination of the nature and scope of environmental psychology. Both its interdisciplinary origins and its applied emphasis have conspired to prevent a straightforward and uncontentious definition of environmental psychology. We review some of these and suggest how recent definitions are beginning to adopt a more inclusive, holistic, and transactional perspective on people-environment relations. The next section discusses the various spatial scales at which environmental psychologists operate—from the micro level such as personal space and individual rooms, public/ private spaces, and public spaces to the macro level of the global environment. This incorporates research on the home, the workplace, the visual impact of buildings, the negative effects of cities, the restorative role of nature, and environmental attitudes and sustainable behaviors. The third section takes three key theoretical perspectives that have informed environmental psychology—determinism, interactionalism, and transactionalism—and uses these as an organizing framework to examine various theories used by environmental psychologists: arousal theory, environmental load, and adaptation level theory within a behaviorist and determinist paradigm; control, stress adaptation, behavioral elasticity, cognitive mapping, and environmental evaluation within an interactionist paradigm; and behavior settings, affordance theory and theories of place, place identity, and place attachment within transactionalism.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The fourth section looks to the future of environmental psychology by challenging the assumptions and limiting perspectives of present research. The issues at the forefront of the political and environmental agenda at the beginning of the twenty-first century—human rights, well-being and quality of life, globalization, and sustainability—need to be addressed and tackled by environmental psychologists in a way that incorporates both cross-cultural and temporal dimensions. The impact of environmental psychology may be enhanced if researchers work within the larger cultural and temporal context that conditions people’s perceptions and behaviors within any given environment. This concluding section discusses some of the work being undertaken by environmental psychologists seeking to meet this challenge and address what some have considered to be an application gap within environmental psychology (i.e., the gap between the generation of general principles and on-the-ground advice of direct use to practitioners).

The Environment as Context

One of the shortcomings of so much psychological research is that it treats the environment simply as a value-free backdrop to human activity and a stage upon which we act out our lives. In essence, the environment is regarded as noise. It is seen as expedient in psychological investigations and experiments to remove or reduce as much extraneous noise as possible that will affect the purity of our results. This is understandable and desirable in many situations, but when it comes to understanding human perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors in real-world settings, the environment is a critical factor that needs to be taken into account.

A paper presented at a recent environmental psychology conference reported on an investigation of children’s classroom design pBibliography:.The study was undertaken by means of showing the children photographs of different classroom layouts. There were three principal methodological flaws that illustrate well the issue of the role and importance of environmental context in psychology. First, the photographs included neither adults nor children. In other words, the photographs did not illustrate or indicate how the environment was actually being used by either children or adults. When the researcher was asked why children and adults were excluded from the photographs, the response was that they would have been a distraction. This is another variant of the failing identified in the previous paragraph. In this case, people are treated as noise and become environmental objects. It is assumed that if we can get people to rate environments preferentially without those environments being contaminated with people, we will arrive at a purer measure of the impact of the environment on human preferences.

The second flaw with this study was that all the photographs were taken at adult height, thereby providing an adult perspective on the environment even though children’s perceptions and pBibliography: were being sought. Finally, all the photographs were taken from an adult point of view (e.g., the framing, focus, what was included and excluded) as if the environment is visually and symbolically neutral. In other words, the researcher thought that taking photographs of the classrooms could provide an objective and impartial view of the environment. If the photographs had been taken by the children from their own perspective, the photographs might have come to mean very different things to the children and brought about a very different evaluation. The environment provides us with opportunities and constraints—sets of affordances—that we can choose to draw upon (Gibson, 1979). Of course, not all children will perceive the same affordances in a single environment, nor will similar environments generate the same perceptions and evaluations in a single child (Wohlwill & Heft, 1987).

It is a characteristic feature of environmental psychology that in any environmental transaction attention should focus on the user of the environment as much as on the environment itself. For example, as it is not possible to understand the architecture and spatial layout of a church, mosque, or synagogue without reference to the liturgical precepts that influenced their design, so it is no less possible to understand any landscape without reference to the different social, economic, and political systems and ideologies that inform them.

One might well imagine, for example, a school landscape that looks extremely tidy, well kempt, with clear demarcation of spaces, producing a controlled and undifferentiated environment with easy surveillance, and with learning and other activities taking place in predetermined spaces. Such a designed environment reflects a traditional view of the passive, empty learner waiting for educational input. If one now imagines a school landscape that appears on the surface to be more haphazard and not so well ordered, unkempt with long grass, soft or even no edges between activities, less easy surveillance, and no obvious places for learning specific curriculum subjects, then this would seem to be antithetic to learning and education. However, if one switches to another model of the child—the child as a stimulus-seeking learner—then the sterile, formal, and rigid landscape just described would seem like an inappropriate place for learning. On the other hand, providing an unstructured, environmentally diverse set of landscapes would seem to be an ideal place for learning, encouraging children to seek out the stimulation that they need for learning and development. Reading the environment in terms of the assumptions it makes about the user is instructive. Understanding and designing the environment for human activity can be achieved only when both the environment and the user are considered together as one transaction.

The environmental setting is not a neutral and value-free space; it is culture bound. It is constantly conveying meanings and messages and is an essential part of human functioning and an integral part of human action. As Getzels (1975) writes, “Our vision of human nature finds expression in the buildings we construct, and these constructions in turn do their silent yet irresistible work of telling us who we are and what we must do” (p. 12). The environment embodies the social and cultural values of those who inhabit it. Some psychologists argue that we need only focus on people because even though the environment contains the manifest evidence of the values and meanings held by people, these values and meanings can be investigated at source (i.e., in the people themselves). As we know that attitudes are not always good predictors of behavior, so we might also assume that what people say about the environment and their actions within it may actually be contradicted by extant evidence from the environment itself. Furthermore, the environment is not just a figment of our imaginations or a social construct; it is real. If we take a determinist or even an interactionist position, we would acknowledge that the environment can have a direct effect on human actions. Within transactionalism the environment has a physical manifestation in order to confer meaning in the first place. The environment embodies the psychologies of those who live in it. It is used to confer meaning, to promote identity, and to locate the person socially, culturally, and economically.

The role of environmental context in influencing social behavior can be exemplified by reference to interpersonal relations as well as institution-person relations. Helping behavior is a good example of the influence of environmental context on the interpersonal behavior. The conclusions of numerous research studies undertaken since the 1970s (Korte, 1980; Korte & Kerr 1975; Krupat, 1985; Merrens, 1973) consistently demonstrate that the conditions of urban life reduce the attention given to others and diminish our willingness to help others.Aggressive reactions to a phone box that is out of order are more common in large cities than in small towns (Moser, 1984). Those findings have been explained by the levels of population densities such as we encounter in large urban areas that engender individualism and an indifference toward others, a malaise noted in 1903 by Simmel (1903/1957), who suggested that city life is characterized by social withdrawal, egoistic behaviors, detachment, and disinterest toward others. The reduction of attention to others can be observed also when the individual is exposed to more isolated supplementary stressful condition (Moser, 1992). Thus, excessive population density or the noise of a pneumatic drill significantly reduces the frequency of different helping behaviors (Moser, 1988). If, generally speaking, politeness (as measured by holding the door for someone at the entry of a large department store) is less frequent in Paris than in a small provincial town, this would suggest that population density and its immediate impact on the throughput of shoppers will affect helping and politeness behavior (Moser & Corroyer, 2001).

A good example of the effect of environmental context on human attitudes and behaviors in an institution-person setting can be found in Rosengren and DeVault’s (1970) study of the ecology of time and space in an obstetric hospital.They found that both the attitudes and behaviors of all the protagonists involved in the process of delivering a baby—the mother, nurses, doctors—were a function not only of where they were situated but also of when they were situated there. Authority (i.e., who managed the mother’s labor and delivery) was not so much a function of a formal position in the hierarchy but of where each person was at a particular time and who controlled that space. This time-space interaction had an impact not only on staff-patient relations but also on perceptions of the appropriateness of medical procedures as they related to the management of pain.

The environmental context in which perceptions occur, attitudes are formed, and behavior takes place also has a temporal dimension. We cannot understand space and place without taking into account time. We encounter events not only in the present but also in the past and in the future. We experience places now, in the present, as well as places that have had a past that impinges on and colors our interpretation of the present. Furthermore, these same places have a future that, for example, through anticipatory representations may guide our actions (Doise, 1976).

The Nature and Scope of Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology studies individuals and groups in their physical and social contexts by giving a prominent place to environmental perceptions, attitudes, evaluations and representations, and accompanying behavior. Environmental psychology focuses both on the effects of environmental conditions on behavior and on how the individual perceives and acts on the environment. The point of departure of analysis is often the physical characteristics of the environment (e.g., noise, pollution, planning and layout of physical space) acting directly on the individual or mediated by social variables in the environment (e.g., crowding, population heterogeneity). But physical and social factors are inextricably linked in their effects on individuals’ perceptions and behaviors (Altman & Rogoff, 1987). To achieve this effectively, research in environmental psychology aims to identify processes that regulate and mediate this relationship. Environmental psychologists work in collaboration with other psychologists such as social, cognitive, and occupational psychologists, as well as other disciplines and professions such as architects, educationalists, environmental scientists, engineers, and landscape architects and planners.

Environmental psychology’s unit of analysis is the individual-environment relation. One can study this relation only by examining cognitions and behaviors that occur in real-world situations. For this reason, environmental psychology operates according to an inductive logic: Theories are generated from what can be observed and from data unearthed in research in the real world. Kurt Lewin’s advocacy of theory-driven practical research ought to have a resonance with environmental psychologists.

The conceptual model by which our perceptions, representations, and behaviors are interdependent with the physical and social environment has frequently been mentioned in psychology. In their work on perception, Brunswik (1959) and Gibson (1950) referred to the role of the environment; Tolman (1948) used the concept of the mental map to describe the cognitive mechanisms that accompany maze learning; and in the domain of the psychology of form Lewin (1951) elaborated the theory of the environmental field, conceived as a series of forces that operate on the individual. Lynch’s study of The Image of the City (1960), although by an urban planner, was another major landmark in the early years of environment-behavior research. The first milestones of environmental psychology date from the late 1960s (Barker, 1968; Craik, 1970; Lee, 1968; Proshansky, Ittelson, & Rivlin, 1970). The intellectual and international origins of environmental psychology are considerably broader than many, typically North American, textbooks suggest (Bonnes & Secchiaroli, 1995).

Although environmental psychology can justly claim to be a subdiscipline in its own right, it clearly has an affinity with other branches of psychology, especially social psychology, but also cognitive, organizational, and developmental psychology. Examples of where environmental psychology has been informed by and contributed to social psychology are intergroup relations, group functioning, performance, identity, conflict, and bystander behavior. However, social psychology often minimizes the role of the environment as a physical and social setting and treats it as simply the stage on which individuals and groups act rather than as an integral part of the plot. Environmental psychology adds an important dimension to social psychology by making sense of differences in behavior and perception according to contextual variables—differences that can be explained only by reference to environmental contingencies.

Although there are strong links to other areas of psychology, environmental psychology is unique among the psychological sciences in terms of the relationship it has forged with the social (e.g., sociology, human ecology, demography), environmental (e.g., environmental sciences, geography), and design (e.g., architecture, planning, landscape architecture, interior design) disciplines.

Because of the difficulties of defining environmental psychology, many writers have sought instead to characterize or describe it, as we ourselves did in part earlier. The most recent of these can be found in the fifth edition of Bell, Greene, Fisher, and Baum’s (2001) textbook Environmental Psychology. They suggested that (a) environmental psychology studies environment-behavior relationships as a unit, rather than separating them into distinct and self-contained elements; (b) environment-behavior relationships are really interrelationships; (c) there is unlikely to be a sharp distinction between applied and basic research; (d) it is part of an international and interdisciplinary field of study; and (e) it employs an eclectic range of methodologies. But description is not a substitute for definition. Leaving aside Proshansky et al.’s (1970, p. 5) oft-quoted “environmental psychology is what environmental psychologists do,” the same authors suggested that “in the long run, the only really satisfactory way . . . is in terms of theory. And the simple fact is that as yet there is no adequate theory, or even the beginnings of a theory, of environmental psychology on which such a definition might be based” (p. 5). By 1978, Bell, Fisher, and Loomis, in the first edition of Environmental Psychology, cautiously suggested that it is “the study of the interrelationship between behavior and the built and natural environment,” although they preferred to opt for the initial Proshansky et al. conclusion. Other, not dissimilar, definitions followed: “an area of psychology whose focus of investigation is the interrelationship between the physical environment and human behavior and experience” (Holahan, 1982, p. 3); “is concerned with the interactions and relationships between people and their environment” (Proshansky, 1990); “the discipline that is concerned with the interactions and relationships between people and their environments” (McAndrew, 1993, p. 2).

The problem with some of these definitions is that although they describe what environmental psychologists do, unfortunately they also hint at what other disciplines do as well. For example, many (human) geographers could probably live quite comfortably with these definitions. By 1995, Veitch and Arkkelin were no less specific and perhaps even enigmatic with the introduction of the word “enhancing”: “a behavioural science that investigates, with an eye towards enhancing, the interrelationships between the physical environment and human behaviour.”

These are clearly not the only definitions of environmental psychology, but they are reasonably representative. The definitions have various noteworthy features. First, because the area is necessarily interdisciplinary, the core theoretical perspectives that should inform our approaches have sometimes been minimized. Thus Bonnes and Secchiaroli (1995) drew attention to the need to define the field as a function of the psychological processes studied. Most definitions of environmental psychology focus on the relationship between the environment and behavior, yet paradoxically most of the research in environmental psychology has not been about behavior but perceptions of and attitudes toward the environment and attitudes toward behavior in the environment. Second, many of the definitions refer to relationships between people and the physical or built environment. Proshansky acknowledged that this was problematic because it fails to recognize the importance of the social environment. The distinction between built and natural environments is becoming increasing untenable given the mutual dependency and reciprocity that exist between them, especially within the context of the sustainability debate. Finally, many of the definitions talk about the individual interacting with the environment. Unfortunately, this ignores or minimizes the social dimension of environmental experience and behavior. This is a strange omission given the strong influence of social psychology on the area, although it is perhaps a reflection of the individualistic nature of much social psychology.

Gifford (1997) more usefully offered the following: “Environmental psychology is the study of transactions between individuals and their physical settings. In these transactions, individuals change the environment and their behaviour and experiences are changed by the environment. Environmental psychology includes research and practice aimed at making buildings more humane and improving our relationship with the natural environment” (p. 1). This far more inclusive definition captures key concepts such as experience, change, people-environment interactions and transactions, and natural versus built environments. As long ago as 1987, Stokols (1987) suggested that “the translation of a transactional world view into operational strategies for theory development and research . . . poses an ambitious but promising agenda for future work in environmental psychology” (p. 41). The essence of a transactional approach, Stokols continued, is “its emphasis on the dynamic interplay between people and their everyday environmental settings, or ‘contexts’ ” (p. 42).

Domains of Environmental Psychology

Environmental psychology deals with the relationship between individuals and their life spaces. That includes not only the environment to provide us with all what we need to survive but also the spaces in which to appreciate, understand, and act to fulfill higher needs and aspirations.

The individual’s cognitions and behaviors gain meaning in relation to the environment in which these cognitions or behaviors are developed. Consequently, environmental psychologists are confronted with the same issues that concern all psychologists. The basic domains of environmental psychology include (a) environmental perceptions and cognitions, (b) environmental values, attitudes, and assessment, and (c) behavioral issues. It studies these processes in relation to the environmental settings and situations in which they occur. For instance, environmental perceptions are not typically studied with the aim of identifying general laws concerning different aspects of the perceived object. Environmental perception deals with built or natural landscape perception with an emphasis on sites treated as entities (Ittelson, 1973); the perceiver is considered part of the scene and projects onto it his or her aspirations and goals, which will have an aesthetic dimension as well as a utilitarian function. The question the perceiver asks in appraising a landscape is not just “Do I like the appearance of this landscape?” but also “What can this landscape do for me (i.e., what function does it serve)?” (Lee, 2001). Likewise, interpersonal behavior within an environmental psychology context is studied in order that we might better understand how environmental settings influence these relationships (e.g., urban constraints on the frequency of relational behavior with friends or relatives; Moser, 1992).

Because of its very focus, environmental psychology has been and remains above all a psychology of space to the extent that it analyzes individuals’ and communities’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors in explicit relation to the physical and social contexts within which people and communities exist. Notions of space and place occupy a central position. The discipline operates, then, at several levels of spatial reference, enabling the investigation of people-environment interactions (at the individual, group, or societal level) at each level. Reference to the spatial dimension makes it possible to take into account different levels of analysis:

- Private spaces (individual level): personal and private space, dwelling, housing, workplace, office

- Public/private environments (neighborhood-community level): semipublic spaces, blocks of flats, the neighborhood, parks, green spaces

- Public environments (individual-community level, inhabitants): involving both built spaces (villages, towns, cities) as well as the natural environment (the countryside, landscape, etc.)

- The global environment (societal level): the environment in its totality, both the built and the natural environment, natural resources

Environmental psychology analyzes and characterizes people-environment interactions and/or transactions at these different environmental levels. These relations can best be understood through perception, needs, opportunities, and means of control.

Private Spaces

Personal space and privacy are important for individual and community well-being and quality of life. Altman (1975, p. 18) defined privacy as the “selective control of access to the self or one’s group.” Thus, privacy implicates control over the immediate environment. It is important for the individual to be able to organize and personalize space. Privacy represents a dynamic process of openness and closeness to others (Altman & Chemers, 1980). Thus, privacy adjustments may be established with physical or even psychological barriers wherever individuals seek to isolate or protect themselves from the intrusion of others. This may be important in one’s home, but also in the work environment or during leisure activities (e.g., on the beach). Privacy involves not only visual but also auditory exclusivity (Sundstrom, Town, Rice, Osborn, & Brill, 1994). Steady or transitionally occupied places produce place attachment and are often accompanied with ties to personal objects such as furniture, pictures, and souvenirs that mark the appropriation (Korosec-Serfaty, 1976). Appropriation can be defined as a particular affective relation to an object. The appropriated object may become part of the identity of the individual (Barbey, 1976). The appropriation of space has essentially a social function in the sense that the individual or the group marks control over the space (Proshansky, 1976), which in turn produces a feeling of security. When appropriation is not shared with others, or only with one’s group, control is absolute.

The use of space in the home or the office environment has produced a variety of studies. The intended function of a room (e.g., kitchen, dormitory, etc.) implies a specific design and determines how the space will be used. There are considerable individual and cultural differences in the use of space in one’s home (Kent, 1991; Newell, 1998; Rapoport, 1969).

Personal space is defined as the invisible boundary surrounding each individual into which others may not intrude without causing discomfort (Hall, 1966). Personal space regulates interactions, and its extension depends on environmental variables. Its functions are twofold: protection, in which it acts as a buffer against various interpersonal threats, and communication purpose, in which it determines which sensory communication-channel (touch, visual, or verbal) can and should be used. Thus, interpersonal distances are cues for understanding the specific relationship of two individuals. Research has looked at various social determinants of personal space such as culture and ethnicity, age and gender (e.g., Aiello, 1987; Crawford & Unger, 2000), psychological factors (Srivastava & Mandal, 1990), and physical factors (Altman & Vinsel, 1977; Evans, Lepore, Shejwal, & Palsane, 1998; Jain, 1993).

In contrast to personal space, territoriality is visibly delimited by boundaries and tends to be home or workplace centered. It is a demarcated and defended space and invariably is an expression of identity and attachment to a place (Sommer, 1969). Territories are controlled spaces that serve to enable the personalization and regularization of intrusion. Therefore, territoriality has an essential function in providing and promoting security, predictability, order, and stability in one’s life. Altman and Chemers (1980) identified three types or levels of territory: primary territories (e.g., home or office space), where control is permanent and high and personalization is manifest; secondary territories (e.g., the classroom or open plan office), where control, ownership, and personalization are temporary; and public territories (e.g., the street, the mall), where there is competition for use, intrusion is difficult to control, and personalization is largely absent.

Public/Private Environments

The Home Environment

Analyses at this level deal with the immediate environment of the individual’s living space. These could be rows of houses or apartment blocks, the immediate neighborhood, the workplace, or the leisure areas in the immediate surroundings of the home (e.g., parks and green areas). These areas are referred to as semipublic or semiprivate spaces, which means that the control over them is shared within a community.

A great deal of research in environmental psychology concerns the immediate home environment. Concepts like attachment to place and sense of community contribute to our understanding of how individuals and groups create bonds to a specific place. Although the size of the habitable space is essential for residential satisfaction, other aspects of the living conditions modulate its importance as well. Residents enhance the value of their neighborhood through the transactional relationships they establish with their place of residence. For those who have already acquired basic living conditions and who have an income that allows them to achieve a good quality of life, the agreeable character of the neighborhood has a modulating effect on satisfaction concerning available space in the dwelling. The affective relationship with the dwelling and anchorage in childhood seem to play an important role. Giuliani (1991) found that affective feelings toward the home were attributable to changing conceptions of the self in relation to the home over the life span.

The feeling of being at home is closely connected to a feeling of well-being and varies with the extent of the spatial representation of the neighborhood. Aspatially narrow representation is correlated with a weak affective investment in the neighborhood (Fleury-Bahi, 1997, 1998). The degree of satisfaction felt with three of a neighborhood’s environmental attributes (green spaces, aesthetics of the built framework, and degree of noise) has an effect on the intensity of the affectivity developed toward it, as well as feelings of wellbeing. The feeling of being at home in one’s neighborhood is linked to the frequency of encounters, the extent of the sphere of close relations, the nature of local relationships, and satisfaction with them. Low and Altman (1992) argued that the origin and development of place attachment is varied and complex, being influenced by biological, environmental, psychological, and sociocultural processes. Furthermore, the social relations that a place signifies may be more important to feelings of attachment than the place itself.

Besides the home and neighborhood environments, other domains involve a problematic congruence between people and their environment (e.g., work, classroom, and institutional environments such as hospitals, prisons, and homes for children or the elderly). How can these environments be designed to meet the needs of their occupants? We illustrate this by examining one setting—the workplace.

Environmental Psychology in the Workplace

Increasing attention is being paid to the design of the workplace so that it matches more effectively the organization’s goals and cultural aspirations as well as employee needs and job demands and performance. There has been a long history of research into the workplace (Becker, 1981; Becker and Steele, 1995; Sundstrom, 1987; Wineman, 1986). Indeed, the famous Hawthorne effect first noted in the 1920s emerged from a study of the effect of illumination on productivity. Since then there have been many studies examining the ambient work environment and investigating the impact of sound, light, furniture layout, and design on performance and job satisfaction. It is now recognized that the environment, space, and design can operate at a subtler level and have an impact on issues such as status, reward, and the promotion of corporate culture.

Decisions about space use and design should be examined for their embedded assumptions regarding how they will enhance or detract from the organization’s goals and values. In other words, whose assumptions underlie the design and management of space, and what are the implications of space-planning decisions? The relationship between the organization’s culture, the physical planning of the buildings or offices, and the feel, look, and use of the facilities becomes most apparent especially when there is a mismatch. A mismatch often occurs when a new building is planned according to criteria such as these: How many people should it accommodate? How many square feet should it occupy? How much equipment should it have? How should it look to visitors? Questions typically posed and addressed by environmental psychologists have a different emphasis: Will the designs and space layout enhance or detract from the desired corporate work styles? Is the organization prepared to accept that employees have different working styles and that these should be catered to in the provision of space and facilities? How much control does the organization currently exert over its employees’ use of time and space? To what extent are employees permitted to modify their own environment so that it enables them to do their job more effectively? In what way, for whom, and how does the management and design permit, encourage, or enhance the following: personal and group recognition, environmental control (heating, lighting, ventilation, amount and type of furniture, personalized space), social integration and identity, communication within the working group, communication with other working groups, and appropriate levels of privacy? How are issues such as individual and group identity; individual capacities, needs, and preferences; and working patterns reflected in space planning and the allocation of environmental resources? Is space and resource allocation used as a means of reflecting and rewarding status and marking distinctions between job classifications? Is the organization prepared to redefine its understanding of equity and provide space and facilities on the basis of need rather than status?

There are many ways of looking at the relationship between corporate culture and physical facilities. The effective use of the organization’s resources lies not in fitting the staff to the workplace but in recognizing that there will be a transaction between staff and workplace so that if the employee cannot or will not be forced into the setting, they will either attempt to modify the setting so that it does approximate more closely their working needs and preferences or become dissatisfied, disaffected, and unproductive. For example, instead of assigning an employee just one space, consideration should be given to permitting if not encouraging. Instead of working in just one place (e.g., a desk), some companies are giving employees access to a number of spaces (e.g., hot desking) that will allow them to undertake their tasks and with more satisfaction and effectiveness. Within such an arrangement staff cannot claim territorial rights over specific spaces but are regarded as temporary lodgers for as long as they need that space: informal privacy spaces for talking to clients and colleagues; quiet, comfortable spaces for writing reports; workstations for undertaking word processing and data analysis; meeting rooms for discussing issues with colleagues; small refreshment areas for informal socializing; and quiet, private telephone suites for confidential matters. There are various possibilities—the type of spaces will depend on the type of work and how it can be undertaken effectively.

Public Environments

Cities are a human creation. They concentrate novelty, intensity, and choice more so than do smaller towns and villages. They provide a variety of cultural, recreational, and educational facilities. Equally, it is argued that cities have become more dangerous because they concentrate all sorts of crime and delinquency and are noisy, overcrowded, and polluted. Three topics addressed at this environmental level are discussed here: the negative effects of cities, the visual impact of buildings, and the restorative role of nature.

The Negative Effects of Cities

Living in metropolitan areas is considered to be stressful. The analysis of behavior in cities has concentrated on noise, density, living conditions (difficulty of access to services), high crime, and delinquency rates. A series of conceptual considerations have been proposed to understand the consequences of these stressors for typical urban behavior, such as paying less attention to others and being less affiliative and less helpful. Environmental overload, environmental stress, and behavioral constraint all point to the potentially negative effects of living in cities as compared with living in small towns. Environmental conditions like noise and crowding not only affect general urban conditions but also have a specific effect on behavior. A comparison of behavior at the same site but under different environmental conditions (noisy-quiet, highlow density) shows a more marked negative effect in the case of high noise and high density (Moser, 1992). Higher crime and delinquency rates are commonly explained by the numerous opportunities that the city offers, along with deindividuation (Zimbardo, 1969). The probability of being recognized is lower, and the criminal can escape without being identified. Fear of crime (which is not necessarily correlated with objective crime rates) restricts people’s behavior by making them feel vulnerable. It is exacerbated by an environment that appears to be uncared for (e.g., through littering and vandalism).

Whereas the effect of air pollution on health (e.g., respiratory problems for children and the elderly) is well documented (Godlee & Walker, 1992; Lewis, Baddeley, Bonham, & Lovett, 1970), it has little direct effect on the behavior of urban residents. The relationship between exposure to air pollution and health is mediated by perceptions of the exposure (Elliot, Cole, Krueger, Voorberg, & Wakefield, 1999). The extent to which people feel that they can control the source of air pollution, for instance, influences their response to this pollution. Perceptions of air pollution are also important because they influence people’s responses to certain strategies for air pollution management. Whether people perceive air pollution as a problem is of course related to the actual existence of the problem. Generally, people are more likely to perceive environmental problems when they can hear (noise), see (smoke), smell, or feel them. Another important source of information is the media because the media’s interpretation of pollution levels may have a social amplification effect and influence public perceptions and attitudes (Kasperson et al., 1988). People believe that heavy-goods vehicles, commuters, and business traffic are the principal sources of urban air pollution. On the otherhand, school traffic is often seen as one of the most important causes of transport problems. It is often argued that reducing school trips by car would make a significant difference to urban transportation problems. Paradoxically, although considered to be a major source of congestion, school traffic is not seen as a major source of pollution (Gatersleben & Uzzell, 2000).

The Visual Impact of Buildings

Most of us live in cities. The architecture that surrounds us is more than public sculpture. Research on the visual impact of buildings demonstrates perhaps more than any other area that different user groups perceive and evaluate the environment dissimilarly.The criteria used most widely by the public to assess the visual impact of a building is how contextually compatible it appears to be with the surrounding environment (Uzzell, 2000b).Architects and their clients, however, tend to value more highly the distinctiveness and contrast of buildings. Although there is a place for both, the indication is that there are diverging points of view on what constitutes a desirable building between groups of people (Hubbard, 1994, 1996). Groat (1994) found differences of opinion to be greatest between the public and architects and most similar between the public and planners. Several studies (e.g., Purcell & Nasar, 1992; Nasar, 1993) have demonstrated that architects and educated laypeople differ in their pBibliography: for building styles and in the meanings that they infer from various styles. For example, Devlin and Nasar (1989) found that architects rated more unusual and distinctive residential architecture as more meaningful, clear, coherent, pleasant, and relaxing, whereas nonarchitects judged more conventional and popular residential architecture as such. Similarly, Nasar (1993) found that not only did architects differ from the public in their pBibliography: and in the meanings that they inferred from different styles, but they also misjudged the pBibliography: of the public.

Individual design features such as color, texture, illumination, and the shape and placement of windows can have a significant impact on evaluations. Overall, such research findings regarding order (including coherence, compatibility, congruity, legibility, and clarity) have been reasonably consistent; increases in order have been found to enhance the evaluative quality of cities (Nasar, 1979), downtown street scenes (Nasar, 1984), and residential scenes (Nasar, 1981, 1983).

The Restorative Role of Nature

Despite city living, many urban residents desire a private house with garden or at least to be able to visit urban parks and recreational areas. Urban residents often seek nature, and research points consistently to its positive psychological function (Staats, Gatersleben, & Hartig, 1997; Staats, Hartig, & Kieviets, 2000). Green spaces and the natural environment can provide not only an aesthetically pleasing setting but also restorative experiences (Kaplan, 1995), including a positive effect on health (Ulrich, 1984; E. O. Moore, 1982). Gifford (1987) summarized this research and identified the following main benefits of nature: cognitive freedom, escape, the experience of nature, ecosystem connectedness, growth, challenge, guidance, sociability, health, and self-control. What seems to be important is the sense of freedom and control felt in nature, in contrast to an urban environment, which is perceived as constraining.

The Global Environment

Local agendas are increasingly informed by global perspectives and processes (Lechner & Boli, 1999). The interaction between the local and the global is crucial and is the essence of globalization (Bauman, 1998; Beck, 1999). Although environmental issues are increasingly seen as international in terms of extent, impact, and necessary response, social psychological studies have traditionally treated many environmental problems as locally centered and limited to a single country. Thus they have been decontextualised in that not only has the local-global environmental dimension been minimized, but perhaps more significantly the local-global social psychological effects have also been minimized. This is well illustrated by Bonaiuto, Breakwell, and Cano (1996), who examined the role of social identity processes as they manifest themselves in place (i.e., local) and national identity in the perception and evaluation of beach pollution. It was found that subjects who were more attracted to their town or their nation tended to perceive their local and national beaches as being less polluted.

Three phenomena—mass media coverage of environmental issues, the growth in environmental organizations, and the placing of environmental issues on international political agendas—have, intentionally or unintentionally, emphasized the seriousness of global as opposed to local or even national environmental problems. On the other hand, it has been suggested that people are only able to relate to environmental issues if they are concrete, immediate, and local. Consequently, it might be hypothesized that people will consider environmental problems to be more serious at a local rather than global level. If this is the case, then what is the effect of the public’s perceptions of the seriousness of environmental problems on their sense of responsibility for taking action? In a series of cross-cultural studies undertaken in Australia, Ireland, Slovakia, and the United Kingdom, members of the public and environmental groups, environmental science students, and children were asked about the seriousness of various environmental problems in terms of their impact on the individual, the local area, the country, the continent, and the world (Uzzell, 2000b). It was consistently found that respondents were able to conceptualize problems at a global level, and an inverse distance effect was found such that environmental problems were perceived to be more serious the farther away they are from the perceiver. This phenomenon repeatedly occurred in each country for all groups. An inverse relationship was also found between a sense of responsibility for environmental problems and spatial scale resulting in feelings of powerlessness at the global level.

We are increasingly conscious of the effect of global environmental processes on local climate. The effects of extreme weather conditions—wind, heat or extreme cold—as, for example,investigatedbySuedfeldandothersinAntarcticsurvey stations, have demonstrated various impacts on individuals (Suedfeld,1998;Weiss,Suedfeld,Steel,&Tanaka,2000).The effect of seasonal daylight availability on mood has been described as seasonal affective disorder (Rosenthal et al., 1984). Likewise, sunlight has been found to enhance positive mood (Cunningham, 1979).

The most significant topic analyzed at the level of global environment is without doubt individuals’ attitudes toward and support of sustainable development. A major challenge for environmental psychology is to enable the understanding and development of strategies to encourage environmentally friendly behavior. There is consistent field research in environmental psychology about the ways to encourage environmentally responsible behavior concerning resources conservation (e.g., energy and water), littering, and recycling. Environmental education, commitment, modeling, feedback, rewards, and disincentives are on the whole effective only if such behavior is reinforced and if opportunities are provided that encourage environmentally friendly behavior.

Growing ecological concern in our societies is attributed to a series of beliefs and attitudes favorable to the environment originally conceptualized by Dunlap (1980) and Dunlap and Van Liere (1984) as the new environmental paradigm and now superseded by the New Ecological Paradigm Scale (Dunlap, Van Liere, Mertig, & Jones, 2000). But it is clear from research that proenvironmental attitudes do not necessarily lead to proenvironmental behaviors. Environmental problems can often be conceptualized as commons dilemma problems (Van Lange,VanVugt, Meertens, & Ruiter, 1998;Vlek, Hendrickx, & Steg, 1993). In psychology this is referred to as a social dilemma. The defining characteristics of such dilemmas are that (a) each participant receives more benefits and less costs for a self-interest choice (e.g., going by car) than for a public interest choice (e.g., cycling) and (b) all participants, as a group, would benefit more if they all choose to act in the public interest (e.g., cycling) than if they all choose to act in selfinterest (e.g., going by car; Gatersleben & Uzzell, in press). The social dilemma paradigm can explain why many people prefer to travel by car even though they are aware of the environmental costs of car use and believe that more sustainable transport options are necessary. It is in the self-interest of every individual to use cars. Nevertheless, it is in the common interest to use other modes of transport. However, single individuals do not cause the problems of car use; nor can they solve them. They are typically collective problems. People therefore feel neither personally responsible for the problems nor in control of the solutions.

Theoretical Perspectives on Key Questions in Environmental Psychology

It was suggested at the beginning of this research paper that the context—the environment—in which people act out their lives is a critical factor in understanding human perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Psychologists have largely ignored this context, assuming that most explanations for behavior are largely person centered rather than person-in-environment centered. Because environmental psychologists are in a position to understand person-in-environment questions, the history of environmental psychology has been strongly influenced by the need to answer questions posed by the practical concerns of architects, planners, and other professions responsible for the planning, design, and management of the environment (Uzzell, 2000a). These questions include the following: How does the environment stimulate behavior, and what happens with excessive stimulation? How does the environment constrain and cause stress? How do we form maps of the environment in our heads and use them to navigate through the environment? What factors are important in people’s evaluations of the built and natural environment, and how satisfied are they with different environments and environmental conditions? What is the influence of the environment or behavior setting on people? What physical properties of the environment facilitate some behaviors and discourage others? Do we have a sense of place? What effect does this have on our identity? In this section we outline some of the approaches that have been taken to answer these questions.

Typically, within environmental psychology these questions have been addressed from one of three perspectives.The first is a determinist and essentially behaviorist perspective that argues that the environment has a direct impact on people’s perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. The second approach has been referred to as interactionism: The environment has an impact on individuals and groups, who in turn respond by having an impact on the environment. The third perspective is transactional in that neither the person nor the environment has priority and neither one be defined without reference to the other. Bonnes and Secchiaroli (1995) suggested that transactionalism has two primary features: the continuous exchange and reciprocity between the individual and the environment, and the primarily active and intentional role of the individual to the environment.

It is impossible in a paper of this length to discuss all the theories that have driven environmental psychology research. The varying scales at which environmental psychologists work, as we have seen, assume different models of man, make different assumptions about people-environment and environment-behavior relations, require different methodologies, and involve different interpretive frameworks. In this section we discuss the three principal approaches that have been employed in environmental psychology to account for people’s behavioral responses to their environmental settings.

Determinist and Behaviorist Approaches

Arousal theory, environmental load, and adaptation level provide good illustrations of theories that are essentially behaviorist in their assumptions and determinist in their environment-behavior orientation.

Arousal Theory

Arousal theory stipulates that the environment provides a certain amount of physiological stimulation that, depending on the individual’s interpretation and attribution of the causes, has particular behavioral effects. Each particular behavior is best performed at a definite level of arousal. The relation between levels of arousal and optimal performance or behavior is curvilinear (Yerkes-Dodson law). Whereas individuals seek stimulation when arousal is too low, too-high levels of arousal produced by either pleasant or unpleasant stimulation or experiences have negative effects on performance and behavior. Anomic behavior in urban environments is attributed to high stimulation levels due to environmental conditions such as excessive noise or crowding (Cohen & Spacapan, 1984). On the other hand, understimulation may occur in certain environments such as the Arctic that cause unease and depression (Suedfeld & Steel, 2000).

The Environmental Load or Overstimulation Approach

According to this model people have a limited capacity to process incoming stimuli, and overload occurs when the incoming stimuli exceed the individual’s capacity to process them. Individuals deal with an overloaded situation by concentrating their attention on the most important aspects of a task or by focusing on a fixed goal, ignoring peripheral stimulation in order to avoid distraction. Paying attention to a particular task in an overloaded situation is very demanding and produces fatigue (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989).Typical aftereffects of being exposed to an overload situation are, according to the overload model, less tolerance to frustration, less attention, and reduced capacity to react in an adaptive way. Milgram (1970) attributed the deterioration of social life in cities to the wide variety of demands on citizens causing a reduced capacity to pay attention to others. The overload approach explains why certain environmental conditions lead to undesirable behavioral consequences such as aggression, lack of helping behavior, and selfishness in urban environments.

Adaptation Level Theory

Adaptation level theory (Wohlwill, 1974) is in certain ways a logical extension of arousal theory and the overload approach. It assumes that there is an intermediate level of stimulation that is individually optimal. Three categories of stimulation can be distinguished: sensory stimulation, social stimulation, and movement. These categories can be described along three dimensions of stimulation: intensity, diversity, and patterning (i.e., the structure and degree of uncertainty of the stimulation). In ideal circumstances a stimulus has to be of average intensity and reasonably diverse, and it must be structured with a reasonable degree of uncertainty. The level of stimulation at which an individual feels comfortable depends on his or her past experience, or, more precisely, on the environmental conditions under which he or she has grown up. This reference level is nevertheless subject to adaptation when individuals change their life environments. If rural people can be very unsettled by urban environments, they may also adapt to this new situation after a certain period of residence. Adaptation level theory postulates an active and dynamic relation of the individual with his or her environment.

Interactionist Approaches

Analyses of the individual’s exposure to environmental stressors in terms of control and of behavioral elasticity, on one hand, and environmental cognition (cognitive mapping, environmental evaluations, etc.), on the other hand, refer typically to an interactionist rationale of individual-environment relations.

Stress and Control

Some authors (Proshansky et al., 1970; Stokols, 1978; Zlutnick & Altman, 1972) consider certain environmental conditions to be constraining to the individual. Similarly, others (Baum, Singer, & Baum, 1981; Evans & Cohen, 1987; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) describe such situations as being stressful. Both approaches lead to conditions as being potentially constraining or stressful and introduce the concept of control. Individuals exposed to such situations engage in coping processes. Coping is an attempt to reestablish or gain control over the situation identified as stressing or constraining. According to the psychological stress model, environmental conditions such as noise, crowding, or daily hassles provoke physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions identified as stress (Lazarus, 1966). Three types of stressors can be distinguished: cataclysmic events (e.g., volcanic eruptions, floods, earthquakes), personal life events (e.g., illness, death, family or work problems), and background conditions (e.g., transportation difficulties, access to services, noise, crowding). Such conditions are potentially stressful according to their nature provided that the individual identifies them as such (Cohen, Evans, Stokols, & Krantz, 1986).

An environment is constraining when something is limiting or prevents individuals from achieving their intentions. This may occur with environmental conditions or stressors like noise or crowding, but also with specific environmental features like fences, barriers, or bad weather.The constraining situation is interpreted by the individual as being out of his or her control. The feeling of not being able to master the situation produces psychological reactance (Brehm, 1966). Unpleasant feelings of being constrained lead the individual to attempt to recover his or her freedom of action in controlling the situation. Having freedom of action or controlling one’s environment seems to be an important aspect of everyday life and individuals’well-being. When people perceive control in a noisy situation, their performance is improved (Glass & Singer, 1972); they are less aggressive (Donnerstein & Wilson, 1976; Moser & Lévy-Leboyer, 1985); and they are moreoftenhelpful(Sherrod&Dowes,1974).Onthecontrary, the perception of loss of control produced by a stressful situation or constraints has several negative consequences on behavior (Barnes, 1981) as well as on well-being and health.

Confronted with a potentially stressful condition, the individual appraises the situation. Appraisals involve both assessing the situation (primary appraisal) and evaluating the possibilities of coping with it (secondary appraisal). The identification of a situation as being stressful depends on cognitive appraisal. Cognitive appraisal of a situation as being potentially disturbing or threatening or even harmful involves an interaction between the objective characteristics of the situation as well as the individual’s interpretation of the situation in light of past experience. The secondary appraisal leads to considering the situation as challenging with reference to a coping strategy. Coping strategies depend on individual and situational factors. They consist of problem-focused, direct action such as fleeing the situation, trying to stop, removing or reducing the identified stressor, or reacting with a cognitive or emotional focus such as reevaluating the threatening aspects of the situation. Reaction to a stressful situation may lead the individual to concentrate on the task, focus on the goals, or ignore or even deny the distracting stimuli. Repeated or steady exposure to stressors may result in adaptation and therefore weaker reactions to this type of situation. If the threatening character of the situation exceeds the coping capacities of the individual, this may cause fatigue and a sense of helplessness (Garber & Seligman, 1981; Seligman, 1975).

The Stress-Adaptation Model

In everyday life the individual is exposed to both background stressors and occasionally to excessive environmental stimulation. Consequently, the individual’s behavior can only be appreciated when considered in a context perceived and evaluated by the persons themselves and in reference to baseline exposure (Moser, 1992). Any exposure to a constraining or disagreeable stimulus invokes a neuro-vegetative reaction. Confronted with such stimulation, the individual mobilizes cognitive strategies and evaluates the aversive situation with reference to her or his threshold of individual and situational tolerance, as well as the context in which exposure occurs. This evaluation creates a stimulation level that is judged against a personal norm of exposure. In response the individual judges the stimulus as being weak, average and tolerable, or strong. Cognitive processes intervene to permit the individual to engage in adaptive behavior to control the situation. A situation in which the constraints are too high or in which stimulation is excessive produces increased physiological arousal, thereby preventing any cognitive intervention and therefore also control of the situation.

Behavioral Elasticity

This model introduces the temporal dimension of exposure to environmental conditions and refers to individual norms of exposure (Moser, in press). The influence of stressors is well documented, but the findings are rarely analyzed in terms of adaptation to long-term or before-after comparisons. Yet one can assume that where there are no constraining factors, individuals will revert to their own set of norms, which are elaborated through their history of exposure. The principle of elasticity provides a good illustration of individual behavior in the context of environmental conditions. Using the principle of elasticity from solids mechanics to characterize the adaptive capacities of individuals exposed to environmental constraints, three essential behavioral specificities as a consequence of changing environmental contingencies can be distinguished: (a) a return to an earlier state (a point of reference) in which constraints were not present, (b) the ability to adapt to a state of constraint as long as the constraint is permanent, and (c) the existence of limits on one’s flexibility. The latter becomes manifest through reduced flexibility in the face of increased constraints, the existence of a breaking point (when the constraints are too great), and the progressive reduction of elasticity as a function of both continuous constraints and of aging.

Returning to an Earlier Baseline. While attention is mostly given to attitude change and modifying behavior in particular situations, the stability over time of these behaviors is rarely analyzed. Yet longitudinal research often shows that proenvironmental behavior re-sorts to the initial state before the constraints were encountered. This has been shown, for instance, in the context of encouraging people to sort their domestic waste (Moser & Matheau, in press) or in levels of concern about global environmental issues (Uzzell, 2000b). Exposure to constraints creates a disequilibrium, and the individual, having a tendency to reincorporate initial behavior, reverts to the earlier state of equilibrium.

Adaptation: The Ability to Put Up With a Constraining Situation in so Far as It Is Continuous. Observing behavior in the urban environment provides evidence of the constraining conditions of the urban context. Residents of large cities walk faster in the street and demonstrate greater withdrawal than do those living in small towns: They look straight ahead, only rarely maintain eye contact with others, and respond less frequently to the various requests for help from other people. In other words, faced with an overstimulating urban environment, people use a filtering process by which they focus their attention on those requests that they evaluate as important, disregarding peripheral stimulation. The constant expression of this type of adaptive behavior suggests that it has become normative. The walking speed of inhabitants of small towns is slower that the walking speed of inhabitants in large cities (Bornstein, 1979). So we can assert that such behavior provides evidence of the individual’s capacity to respond to particular environmentally constraining conditions.

The Extent and Limits of Flexibility. The limits of flexibility and, more particularly, the breakdown following constraints that are too great are best seen in aggressive behavior. The distinction between instrumental and hostile aggression (Feshbach, 1964) recalls the distinction between adaptive behavior aimed at effectively confronting a threat and a reactive and impulsive behavior ineffectual for adaptation. Three limits of flexibility can be identified. First is reduced flexibility in the face of increased constraints. When exposure to accustomed constraints is relatively high, there is a lower probability of performing an adaptive response, and therefore an increase in reactive behaviors. There is decreased flexibility in the face of constraint, more so if the constraint is added onto already-existing constraints affecting the individual. This is most clearly evident in aggressive behaviors (Moser, 1984). People react more strongly to the same stimulation in the urban environment than in small towns. Hostile aggression thus becomes more frequent. This results in a decrease in adaptive capacities and therefore of flexibility if additional constraints are grafted onto those already present. The second limit is the existence of a breaking point when the constraints are too great: Intervention by cognitive processes is prevented if stimulation produces a neuro-vegetative reaction that is too extreme (Moser, 1992; Zillmann, 1978). This is most evident with violent or hostile aggressive behavior. This involves nonadaptive reactive behavior that is clearly of a different order. As a consequence, breakdown and a limit on flexibility result. Contrary to what occurs when there is elasticity, however, this breakdown fortunately occurs only occasionally and on an ad hoc basis. The third limit is the progressive loss of elasticity as a function of the persistence of exposure to constraints: This has been examined under laboratory conditions in the form of postexposure effects. Outside the laboratory, the constant mobilization of coping processes, for example, for those living near airports produces fatigue and lowers the capacity to face new stressful situations (Altman, 1975). One encounters, in particular, greater vulnerability and irritability as well as a significant decrease in the ability to resist stressful events. These effects demonstrate that there is a decreased tolerance threshold, and so a decreased flexibility following prolonged exposure to different environmental constraints.

The elasticity model is an appropriate framework to illustrate the mechanisms and limits of behavioral plasticity. It may perhaps stimulate the generation of a model of behavioral adjustments by placing an emphasis on the temporal dimension and the cognitive processes governing behavior. Environmental cognition, cognitive mapping, and environmental appraisals are likely to fall within an interactionist framework. While they can be individualistic, they are invariably set within a social context. Environmental cognition would be enriched by more research in terms of social representations (Moscovici, 1989) providing the opportunity to emphasize the role of cultural values, aspirations, and needs as a frame of reference for environmental behavior.

Cognitive Mapping

How do we form maps of the environment in our heads and use them to navigate through the environment? Cognition and memory of places produce mental images of our environment. The individual has an organized mental representation of his or her environment (e.g., neighborhood, district, city, specific places), which environmental psychologist call cognitive maps. Cities need to be legible so that people can “read” and navigate them. The study of cognitive maps has its origin in the work of Tolman (1948), who studied the way in which rats find their ways in mazes. Lynch (1960), an urban planner, introduced the topic and a methodology to study the ways in which people perceive the urban environment. Lynch established a simple but effective method to collect and analyze mental maps. He suggested that people categorize the city according to five key elements: paths (e.g., streets, lanes), edges (e.g., spatial limits such as rivers and rail tracks), districts (e.g., larger spatial areas or neighborhoods that have specific characteristics and are typically named, such as Soho), nodes (e.g., intersections, plazas), and landmarks (e.g., reference points for the majority of people).

Furthermore, one can distinguish sequential representations (i.e., elements that the individual encounters when traveling from one point of the city to another, rich in paths and nodes) and spatial representations emphasizing landmarks and districts (Appleyard, 1970). Cognitive maps will vary, for example, as a function of familiarity with the city and stage in the life cycle. Such maps can be used to characterize either an individual’s specific environment interests or pBibliography: (Milgram & Jodelet, 1976) or the qualities and legibility of a particular environment (Gärling & Evans, 1991; Kitchen, Blades, & Golledge, 1997). Way finding is a complex process involving a variety of cognitive operations such as localization of the target and choosing the route and the type of transportation to reach the goal (Gärling, Böök, & Lindberg, 1986). Sketch maps often carry typical errors that point to the cognitive elaboration of the individual’s environmental representation: nonexhaustive, spatial distortions (too close, too apart), simplification of paths and spaces, and overestimation of the size of familiar places.

Environmental Evaluations

What factors are important in people’s evaluation of the built and natural environment, and how satisfied are they with different environments and environmental conditions? Some environmental evaluations, called the place-centered method, focus on the objective physical properties of the environment such as pollution levels or the amount of urban development over the previous 10 years. The aim is to measure the qualities of an environment by experts or by actual or potential users. Such evaluations are done without taking into account the referential framework of the evaluator (i.e. the values, preferences, or significations attached to the place). These kinds of appraisals are important, but when it is remembered that what may be an environmental problem for one person may be of no consequence to another, it is clear that environmental assessment has an important subjective dimension as well. This person-centered method focuses on the feelings, subjective appreciation of, and satisfaction with a particular environment (Craik & Zube, 1976; Russell & Lanius, 1984).

Some environmental appraisals take the form of contrasting social categories such as architects versus the public (Groat, 1994; Hubbard, 1994) or scientists versus laypeople (Mertz, Slovic, & Purchase, 1998) or of categorizing people who hold particular attitudes (e.g., pro- vs. anticonservation; Nord, Luloff, & Bridger, 1998). The focus of attention is on the role the individual occupies or the attitudes held and the consequent effect that this has on environmental attitudes and behavior.

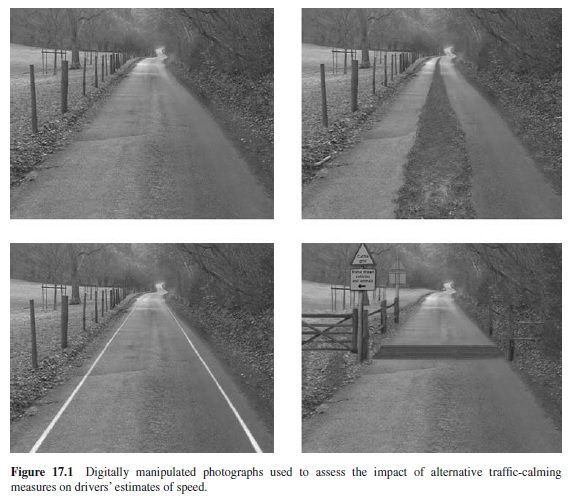

Evaluations can be carried out either in the environment that is being evaluated or through simulations. Horswill and McKenna (1999) developed a video-based technique for measuring drivers’ speed choice, and their technique has the advantage of maintaining experimental control and ensuring external and ecological validity. They found that speed choice during video simulation related highly to real driving experiences. Research consistently confirms color photographs as a valid measure of on-site response, especially for visual issues (Bateson & Hui, 1992; Brown, Daniel, Richards, & King, 1988; Nasar & Hong, 1999; Stamps, 1990). Stamps (1990) conducted a meta-analysis of research that had previously used simulated environments to measure perceptions of real versus photographed environments (e.g., presented as slides, color prints, and black-and-white prints). He demonstrated that there is highly significant correlation between evaluations of real and simulated (photographed) environments. The advent of digital imaging means that it is now possible to manipulate photographs so that environments can be changed in a systematic and highly convincing way in order to assess public pBibliography: and reactions. The photographs in Figure 17.1 were manipulated with the intention of assessing the impact of different traffic calming measures on drivers’ estimates of speed (Uzzell & Leach, 2001).

The research demonstrated that drivers clearly were able to discriminate between the different conditions presented in manipulated photographs. When estimated speeds were correlated against actual speeds along the road as it exists at present, this suggested which design solutions would lead to an increase or decrease in speeding behavior.

Transactional Approaches

Three approaches are discussed here as examples of transactional approaches in environmental psychology: Barker’s behavior setting approach; affordances; and place theory, identity, and attachment.

Barker’s Behavior Settings

Barker’s behavior settings approach has both a theoretical and methodological importance because it provides a framework for analyzing the logic of behavior in particular settings. Barker (1968, 1990) considered the environment as a place where prescribed patterns of behavior, called programs, occur. There is a correspondence between the nature of the physical milieu and a determined number and type of collective behavior taking place in it. According to ecological psychology, knowing the setting will provide information about the number of programs (i.e., behaviors) in it. Such programs are recurrent activities, regularly performed by persons holding specific roles. A church, for instance, induces behaviors like explaining, listening, praying, singing, and so on, but each type of activity is performed by persons endorsing specific roles. According to his or her role, the priest is a performer and the congregation members are nonperformers. This setting also has a layout and particular furniture that fits that purpose and fixes the program (i.e., what type of behavior should happen in it). The so-called behavior setting (i.e., the physical place and the behaviors) determines what type of behavior is appropriate and therefore can or should occur. Patterns of behavior (e.g., worshipping) as well as settings (e.g., churches) are nevertheless independent: A religious office can be held in the open air, and the church can be used for a concert. It is their role-environment structure or synomorphology that create the behavior setting. Barker’s analysis supposes an interdependency between collective patterns of behavior, the program, and the physical space or milieu in which these behaviors take place. Behaviors are supposed to be unique in the specific setting and dependent on the setting in which they occur. Settings are delimited places such as within walls, fences, or symbolic barriers. They can be identified and described. Barriers between settings also delimit programs. Knowing about the setting (e.g., its purpose or intention) infers the typical behaviors of the people in that setting. Barker’s conceptualization permits an understanding of environment-behavior relationships such that space might be organized in a certain way in order to meet its various purposes. Behavior settings are dynamic structures that evolve over time (Wicker, 1979, 1987).

Staffing (formerly manning) theory completes Barker’s approach by proposing a set of concepts related to the number of people that the behavior setting needs in order to be functional (Barker, 1960; Wicker & Kirkmeyer, 1976). Besides key concepts like performers who carry out the primary tasks and the nonperformers who observe, the minimum number of people needed to maintain the functioning of a behavior setting is called the maintenance minimum, and the maximum is called its capacity. Applicants are people seeking to become part of the behavior setting. Overstaffing or understaffing is a consequence of too few or too many applicants for a behavior setting. The consequence of understaffing is that people have to work harder and must endorse a greater range of different roles in order to maintain the functioning of the setting. They will also feel more committed to the group and endorse more important roles. On the other hand, overstaffing requires the fulfillment of adaptive measures to maintain the functioning, such as increasing the size of the setting.

Behavior settings and staffing theory are helpful tools to solve environmental design problems and to improve the functioning of environments. Barker’s approach has been applied successfully to the analyses of work environments, schools, and small towns. It helps to document community life and enables the evaluation of the structure of organizations in terms of efficiency and responsibility.

Affordance Theory

Gibson (1979) argued that, contrary to the orthodox view held in the design professions, people do not see form and shape when perceiving a place. Rather, the environment can be seen as offering a set of affordances; that is, the environment is assessed in terms of what it can do for us. The design professions are typically taught that the building blocks of perception comprise shape, color, and form. This stems from the view that architecture and landscape architecture are often taught as visual arts rather than as ways of providing functional space in which people can work, live, and engage in recreation. Gibson argues that “the affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes either for good or ill” (p. 127). Affordances are ecological resources from a functional point of view. They are an objectively specifiable and psychologically meaningful taxonomy of the environment. The environment offers opportunities for use and manipulation. How we use the environment as children, parents, or senior citizens will vary depending on our needs and interests, values, and aspirations.