View sample close relationship research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In this research paper we draw links between well-being in close relationships and the application of fairness rules in those relationships. In doing so we discuss and link two literatures: a large (and growing) literature on close relationships and a far smaller (and increasingly less active) literature dealing with distributive justice rules and perceptions of fairness in intimate relationships. In sketching out links we set forth some theoretical ideas both about what constitutes a high-quality relationship and about how use of fairness norms relates to the quality of what are often called close relationships— friendships, romantic relationships, marriages, and family relationships.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Defining Quality Relationships

What constitutes a good, high-quality friendship, dating relationship, marriage, or family relationship? What differentiates a high-quality close relationship from one of lower quality? Surprisingly, until quite recently most social and even clinical psychologists had not tackled this question. We attempt to do so in this research paper. First, though, because relationship quality often has been equated with relationship stability, with relationship satisfaction, or with the lack of conflict in a relationship, we begin with arguments against using those relationship characteristics as indexes of the overall quality of a relationship.

Stability Is Not Enough

Although at first blush equating relationship stability and relationship quality seems reasonable, making this general assumption is unwise. After all, many stable relationships are characterized by unhappiness. Interdependence theorists provide straightforward explanations as to why this is sometimes the case (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult, Arriaga, & Agnew, 2001; Rusbult & Van Lange, 1996). Satisfaction, they point out, is just one determinant of commitment to stay in relationships. Other powerful determinants of relationship stability can keep people in relationships despite unhappiness with that relationship.

First, the more one has invested in a relationship, the less likely one is to leave that relationship (Rusbult, 1983). Investments include such things as joint memories, financial investments, friends, possessions, and children. Second, the poorer one’s alternatives to a relationship, including the alternative of being on one’s own, the less likely one is to leave the relationship (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult & Martz, 1995). A woman might stay in an abusive relationship if she perceives her alternatives to be worse, including the option of being alone with no job skills and no financial resources. Finally, personal and social prescriptives against leaving relationships can keep a person within a relationship in which satisfaction is low (Cox, Wesler, Rusbult, & Gaines, 1997). Aperson may have a quite miserable relationship with his or her child yet stay due to very strong personal and societal beliefs that one should never abandon one’s child.

Satisfaction Is Not Enough

What about satisfaction? Are relationship members’ ratings of their own satisfaction with their relationship valid indexes of the existence of a good relationship? Such ratings often have been used in this way, and we do believe that these are better indexes of the existence of a good relationship than is relationship stability. Problems remain, however, and interdependence theorists again provide us with good reasons not to accept satisfaction as the sine qua non of a good relationship.

They point out that satisfaction is only partially determined by the rewards and costs associated with our relationships. A person’s comparison level for a relationship is another important determinant of satisfaction (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978). A person’s comparison level for a particular relationship is what that person expects (or feels he or she deserves) from that relationship. It is the person’s set of standards for the relationship. If a person has had poor-quality relationships in the past, a current relationship that objective observers judge to be a bad relationship might, to that person, seem quite good compared to his or her expectations. In contrast, if a person has had terrific-quality relationships in the past, a current relationship that objective observers judge to be quite good might seem, to that person, to be quite unsatisfactory by comparison.

Another reason satisfaction ratings are not terrific measuresofrelationshipqualityisthattheyaregenerallycollected from a single individual or, at best, from each member of a relationship independently. However, relationship quality is the characteristic of a dyad. It is certainly possible for one person to report being very satisfied with a relationship and his or her partner to report being very unsatisfied with the relationship. What would we then say the quality of the relationship was? For these reasons we do not believe that member satisfaction is the ideal way to judge the quality of a relationship.

Lack of Conflict Is Not Enough

Although many researchers have used the absence of conflict as an index of high-quality relationships and the presence of conflict as an index of low-quality relationships, we believe that such measures are flawed for two reasons. First, it is certainly possible for a relationship to be characterized by low conflict and, simultaneously, by low mutual sharing of concerns and low mutual support. We would not consider this to be a high-quality relationship. For instance, two spouses may lead largely independent lives while sharing the same home. Each may go about his or her business with little or no reliance on the other. Conflict in such a relationship would be quite low, but so too would mutual sharing of concerns, comfort, and support. Indeed, many researchers define interdependence as the very essence of a relationship. They would not view such a relationship as being much of a relationship at all, much less a high-quality one.

Second, we would not consider all conflict to be bad for relationships. Conflict often arises when one person in a relationship feels that his or her needs have been neglected. Raising this as a concern and working it out with a partner may give rise to conflict. However, at the same time, if the conflict is resolved to both persons’ satisfaction, the relationship is likely to have been improved relative to what it had been prior to the conflict. This logic suggests that the presence of some conflict in a close relationship (as long as it is dealt with in a constructive fashion) may actually be a positive indicator of relationship quality.

Good Relationships Foster Members’Well-Being

Having rejected stability and satisfaction as valid indexes of good relationships, we suggest that high-quality relationships are ones in which members behave in such a manner as to foster the well-being of their partners. We define well-being, in turn, as each member’s good physical and mental health and each member’s being able to strive toward and reach desired individual and joint goals.

We further suggest that the best way to define such relationships is in terms of the interpersonal processes (and their impact on individual well-being) that characterize relationships. By identifying interpersonal processes likely to foster well-being in relationships, not only can we define highquality relationships, but, simultaneously, we can also come to understand just why such relationships are of high quality.

This said, recent research suggests that good relationships are those in which each member (a) feels an ongoing responsibility for the other member’s welfare and acts on that feeling by noncontingently meeting the needs of the partner and (b) feels comfortable and happy about that responsibility; in addition, in most mutual, adult, equal-status relationships each member (c) firmly believes that his or her partner feels a similar sense of responsibility for his or her own welfare and relies on that feeling by turning to the other for support without feeling obligated to repay and (d) believes that the other feels comfortable and happy about that responsibility.

Members of high-quality mutual friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships trust each other, feel secure with each other, and derive satisfaction from nurturing each other. They understand, validate, and care for each other. They keep track of each other’s needs (Clark, Mills, & Powell, 1986), help each other (Clark, Ouellette, Powell, & Milberg, 1987), and feel good about doing so (Williamson & Clark, 1989, 1992). They feel bad when they fail to help (Williamson, Pegalis, Behan, & Clark, 1996). They respond to oneanother’sdistressandevenangerwithaccommodationand support (Finkel & Campbell, 2001; Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991) rather than with reciprocal expressions of distress and anger or with defensiveness (Gottman, 1979). They express their emotions to their partners (Clark, Fitness, & Brissette, 2001; Feeney, 1995, 1999). They turn to one another for help (Simpson, Rholes, & Nelligan, 1992). They are willing to forgive one another’s transgressions (McCullough, 2000). Further, members of such relationships are likely to hold positive illusions about partners that, in turn, bring out the best in those partners (Murray & Holmes, 1997; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996a, 1996b; Murray, Holmes, Dolderman, & Griffin, 2000) and to possess cognitive structures in which even their partner’s apparent faults are linked to virtues (Murray & Holmes, 1993). Finally, members of such relationships appear ready to engage in some active relationship-protecting processes such as viewing their own relationship as being better than those of others (Johnson & Rusbult, 1989; Simpson, Gangestad, & Lerma, 1990; Van Lange & Rusbult, 1995). All these things contribute to a sense of intimacy between partners (Reis & Patrick, 1996; Reis & Shaver, 1988) and relationship members’having the sense that their relationship is a safe haven (Collins & Feeney, 2000).

Relationship researchers do not have a single name for what we are describing as a high-quality relationship. Rather, several terms currently in use describe different aspects of such a relationship. We have called relationships in which people assume responsibility for another’s well-being and that benefit that person without expecting repayments communal relationships (Clark & Mills, 1979, 1993). However, assuming responsibility for another person’s needs and striving to meet those needs on a noncontingent basis does not necessarily imply that one is competent or successful at so doing. Other terms in the literature for relationships imply success at following such norms. For example, relationships in which members successfully attend to, understand, validate, and effectively care for one another have been called intimate relationships by Reis and Shaver (1988; Reis & Patrick, 1996). Relationships in which members view the other as one who does care for their welfare and themselves as worthy of such are have been called secure relationships by attachment researchers (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Collins & Allard, 2001; Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Simpson et al., 1992). From our perspective, the exact terminology is not that important—an understanding of the interpersonal processes characterizing these relationships is important.

Agreement on Levels of Responsibility Matters

It is not sufficient just to characterize high-quality friendships, romantic relationships, marriages, and family relationships as those in which members assume responsibility for a partner’s welfare. It is also important, in our opinion, for members to assume the “right” levels of such responsibility. Of course, it is possible and easy to understand that a relationship might be of low quality because members of a relationship do too little to foster the other’s welfare. That seems obvious. A parent who fails to feed his or her child adequately clearly does not have a high-quality relationship with that child. Spouses who ignore one another’s needs clearly do not have a high-quality relationship. Less obviously, it is also possible for members to do too much to foster the other’s welfare. A person who receives an extravagant, expensive present from a casual friend is likely to feel quite uncomfortable and indebted and is unlikely to describe the relationship as high quality. A very young child might feel as if he must comfort his constantly distressed mother and do so. Objective observers would not consider this to be a sign of a high-quality relationship. Indeed, they are likely to consider this to be a sign of poor parenting. So, how are we to understand what degree of responsiveness to another’s needs is right for a relationship?

We suspect that almost everyone has a hierarchy of what we call communal relationships. By this we mean that people have a set of relationships with others about whose needs they believe they ought to care and to whose needs they believe they ought to strive to be responsive in a noncontingent fashion (Clark & Mills, 1993; Mills & Clark, 1982). These relationships vary from weak to strong, with strength referring to the degree of responsibility the person believes he or she ought to assume for the other’s welfare. One end of the hierarchy is anchored by relationships in which the person feels a very low degree of responsibility for the partner’s needs (e.g., a relationship with an acquaintance for whom the person might provide directions or the time of day with no expectation of compensation). The other end of the hierarchy is anchored by relationships in which the person assumes tremendous responsibility for the other’s needs (e.g., a parent-child relationship in which the parent would do just about anything at any cost to ensure the child’s welfare.)

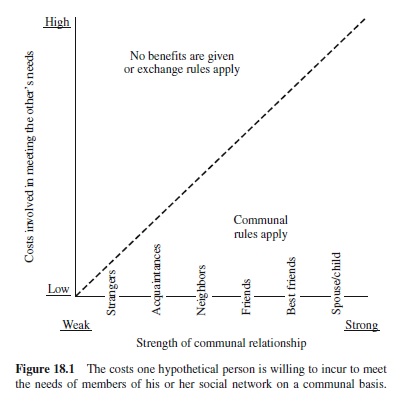

Figure 18.1 depicts one hypothetical person’s hierarchy of communal relationships. Communal relationships, from weak to strong, are depicted on the x-axis. The costs one is willing to incur to meet the other’s needs (noncontingently) are depicted on the y-axis. The dashed line in the figure depicts the costs the person is willing to incur in order to benefit the other on a communal basis.

Beneath the implicit cost line benefits will be given and accepted on a communal, need, basis. Thus, for instance, strangers give one another the time of day, neighbors take in oneanother’smailonatemporarybasis,friendsthrowbirthday parties for one another and travel to one another’s weddings, and parents spend years raising children and tremendous amounts of money to support those children.

Above the cost line benefits are generally not given or even considered. When they are given, they are given on an exchange basis. Consider, for instance, a relationship partner who needs a car. This is a costly benefit and one that falls above the cost line for most relationships, such as those with acquaintances, neighbors, or friends. Under most circumstances this means that this benefit will not be given (or asked for) in such relationships. The topic simply will not come up. However, a person might sell his car to a friend (an economic exchange in which the parties agree that the money and the care are of equal value). Neighbors might agree to provide each other’s child with rides to and from soccer practice following a rule of equality (half the days one person drives, half the days the other drives), and so forth.

Recognizing the existence of hierarchies of communal relationships should help to understand the nature of highquality personal (communal) relationships.As we said earlier, these relationships are characterized by assumed, noncontingent responsibility for a partner’s needs. Here we add that the level of responsibility actually assumed on the part of a caregiver or expected on the part of a person in need (in the absence of true emergencies) ought also to be appropriate to the location of that relationship in its members’ hierarchy of relationships. If the costs involved in meeting the need fall beneath the implicit cost boundary shown in Figure 18.1, the responsiveness ought to be present. If costs exceed the boundary, benefits should not be given, except for emergencies or in instances in which both members wish to strengthen the communal nature of the relationship. Indeed, giving a benefit that falls above the implicit cost boundary might harm the quality of the relationship. So too may asking for too costly a benefit or implying the existence of too strong a communal relationship by self-disclosing too much (Chaiken & Derlega, 1974; Kaplan, Firestone, Degnore, & Morre, 1974) be likely to hurt the relationship.

This should help to explain why responsiveness must be within appropriate bounds even though responsiveness to needs is a hallmark of good relationships. A casual friend should not give one an extravagant present. It exceeds the appropriate level of responsiveness to needs. Ayoung child is not supposed to assume a great deal of communal responsibility for his or her parent. Thus, a child consistently comforting a troubled parent is not a sign of a high-quality relationship. In contrast, a parent is supposed to assume great communal responsibility for his or her child. Thus, a parent consistently comforting his or her troubled child is a sign of a high-quality relationship.

Necessary Abilities and Fortitudes

Having a hierarchy of communal relationships in which one believes one should behave communally (up to an implicit cost level) is one thing. Actually pulling off the task of appropriately and skillfully attending to one another’s needs in such relationships is quite another thing. For mutually supportive, trusting, secure, and intimate communal relationships to exist and to thrive, members must have three distinct sets of skills. One set allows for responding to one’s partner’s needs effectively.Asecond set allows for eliciting a partner’s attention to one’s own needs.The third set involves being able to distinguish successfully when one ought to behave in accord with communal rules and when the application of such rules is socially inappropriate.

Responding Effectively to a Partner’s Needs

Skills and fortitudes necessary to respond effectively to a partner’s needs include empathic accuracy (Ickes, 1993) and the ability to draw out one’s partner’s worries and emotional states (Miller, Berg, & Archer, 1983; Purvis, Dabbs, & Hopper, 1984). Many studies support the idea that understanding a spouse’s thoughts, beliefs, and feelings is linked with good marital adjustment (e.g., Christensen & Wallace, 1976; Noller, 1980, 1981; Gottman & Porterfield, 1981; Guthrie & Noller, 1988). Another skill important to meeting a partner’s needs is knowing when and how to offer help in such a way that it will not threaten the potential recipient’s self-esteem or make the potential recipient feel indebted, but will be accepted. Still another skill important to meeting a partner’s needs is the ability to give help that the partner (not the self) desires and from which the partner (not the self) will benefit. To do so requires accurate perception of differences in needs between the self and the partner. Many parents go wrong in this regard. They may impose their needs on the child and may be seen by outsiders as living “through their child,” often to the detriment of the child.

Some of these abilities require learning, practice, and intelligence (e.g., the ability to draw a partner out, empathic accuracy, and provision of emotional support). The keys to others may lie more in emotional fortitudes. A person may wish to express empathy or offer help but fail to do so out of fear of appearing awkward or being rejected. One’s history of personal relationships in general and one’s history within the particular relationship in question provide explanations for a lack of emotional fortitude in providing help. If one’s past partners (or current partner) have not been open to accepting help in the past, then the person is likely to be reluctant to offer care. A lack of fortitude may also stem from temporary factors. When temporarily stressed or in a bad mood, people may not feel that they have the energy to help because they may be especially likely to anticipate that negative outcomes will be associated with helping (Clark & Waddell, 1983).

Alerting Partners to Your Needs

Next consider skills and fortitudes necessary for eliciting needed support for the self from one’s partner. In this regard, freely expressing one’s own need states to the partner through self-disclosure and emotional expression should be important. After all, a partner cannot respond to needs without knowing what they are. Given this, it is not surprising to us that self-disclosure has been found to increase positive affect (Vittengl & Holt, 2000), liking (Collins & Miller, 1994), and satisfaction in dating relationships (Fitzpatrick & Sollie, 1999), marriages (Meeks, Hendrick, & Hendrick, 1998), and sibling relationships (Howe, Aquan-Assee, Bukowski, Rinaldi, & Lenoux, 2000). Of course, one ought also to be able to ask outright for help and accept it when it is offered. Perhaps less obviously, possessing the ability to say “no” to requests from the partner that interfere with one’s needs ought to be crucial to the partner’s being attentive and responsive to one’s needs. It should also be important that, over time, one demonstrates that one does not exaggerate needs or constantly seek help when it is not needed (Mills & Clark, 1986). This ought to increase a partner’s sense that one is appropriately, and not overly, dependent.

Although help-seeking skills might seem easy, enacting them requires certain emotional fortitudes. In particular, exercising all these skills probably requires having the firm sense that one’s partner truly cares for one and will, indeed, meet one’s needs to the best of his or her ability. Otherwise, self-disclosure, emotional expression, and asking for help seem inadvisable. Under such circumstances, one risks being rebuffed, rejected, or evaluated negatively. The partner may even use information to mock or exploit the other. Negative assertion on one’s own behalf may also be frightening, as it too many provide a basis for rejection. Thus it may seem best not to seek help and not to assert oneself. However, if one does not do so, keeping the relationship on a communal basis becomes difficult. It is for just these reasons that we believe that a sense of trust and security in relationships is key to following communal norms.

Knowing When to Be Communal

Applying communal rules effectively within appropriate bounds requires the skills and fortitudes just mentioned. Avoiding their use in nonemergency situations outside those bounds may require additional fortitudes. One must be able to detect whether the other desires a communal relationship and, if so, at what strength. Being too anxious for intimate communal relationships may lead one to behave communally in inappropriate situations.Work by attachment researchers suggests that this is something that anxious, ambivalent, or preoccupied people often do (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Simpson & Rholes, 1998).

Linking Relationship and Justice Research

Having reviewed some relationship work suggesting what interpersonal processes and interpersonal skills make a personal relationship such as a friendship, romantic relationship, marriage, or family relationship a high-quality relationship, we turn to linking this work to work on the use of distributive justice rules. In this regard we have already made clear that we believe that benefits are ideally distributed according to needs (and not inputs) in relationships such as friendships, romantic relationships, marriages, and family relationships. We have also made clear that we believe such responsiveness should be noncontingent.

Our views fit well with some past work on distributive justice. Specifically, our views fit well with work supporting the idea that use of a needs-based norm governing the giving and receiving of benefits is preferred to using other distributive justice norms in personal relationships (Clark et al., 1986; Clark et al., 1987; Deutsch, 1975, 1985, for family relationships; Lamm & Schwinger, 1980, 1983). At the same time, our views conflict with the arguments of many other distributive justice researchers who have claimed that following other rules—rules such as equity (Walster, Walster, & Berscheid, 1978; Sabatelli & Cecil-Pigo, 1985; Sprecher, 1986; Utne, Hatfield, Traupman, & Greenberger, 1984) or equality (Austin, 1980; Deutsch, 1975, 1985, for friendships)—are best for friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships. It also conflicts with the view that an individual solely watching out for his or her own welfare is best in such relationships (Cate, Lloyd, & Henton, 1985; Huston & Burgess, 1979).

Are we right? Is following a noncontingent, responsivenessto-needs rule best for personal relationships? Is it better than rules of equality or equity? If so, why? We think it is best, and we make the following theoretical and empirical case for this viewpoint.

Following Communal NormsAffords Security; Following Contingent Norms Undermines Security

The reason we believe that following a communal rule is ideal for ongoing intimate relationships is that it is the only rule that can afford members of the relationship the sense that the other truly cares for their welfare. If another responds to one’s needs on a noncontingent basis, the logical inference is that the other truly cares for oneself. This, in turn should heighten trust in the other and promote a sense of security. Instances in which the other benefits a person at some cost to him- or herself should be especially likely to heighten trust (Holmes & Rempel, 1989).

Note that, by definition, contingent distributive justice norms (equity, equality, exchange) involve receiving benefits as conditions of benefiting a person. In contrast, a need-based or communal norm dictates noncontingent giving and acceptance of benefits. Thus, communal responsiveness should be uniquely valuable in terms of providing recipients of care with a sense of being valued and cared for—two of the components Reis and Shaver (1988) pointed out as essential for attaining a sense of intimacy in relationships.

Looking at this from the perspective of the person who gives help also provides insight into the importance of following a communal norm in friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships. At the same time that noncontingent provision of benefits should cause a recipient to feel valued and cared for, so too should it cause the donor of the benefit to see him- or herself as a nurturant, caring individual. This is simply a matter of self-perception. Both feeling cared for and judging oneself to be a nurturant individual are, we suspect, deeply satisfying. It is just these feelings, we believe, that form the essence of what people desire from their friendships, family relationships, and romantic relationships.

People Advocate and Follow Communal Norms

Not only do we believe that—ideally and often in practice— people follow a communal rule in their intimate relationships and do not keep track of individual inputs and outcomes from a relationship, participants in our studies share our belief (Grote & Clark, 1998; Clark & Grote, 2001). What we did to examine this is straightforward: We asked people. First, we came up with prototype descriptions of a number of ways in which people might choose to distribute benefits within their intimate relationships. That is, we made up descriptions of communal rule, an exchange rule, an equity rule, and an equality rule. Then we had people in a number of different types of close, personal relationships (i.e., friendships, dating relationships, marriages) rate the extent to which they viewed these rules to be ideal for their relationship (from 3 indicating “not at all ideal” to 3 indicating “extremely ideal”). They also rated each rule according to the extent to which they thought it was realistic on a similar scale.

In each case the communal rule was rated as ideal for these relationships and as substantially more ideal than were any of the remaining rules (the ratings generally fell on the “not ideal” ends of the scales). In each case the communal rule also was rated as being on the realistic side of the scales and as being more realistic than any of the remaining rules.

Use of Communal Norms and Relationship Satisfaction

Some evidence that a tendency to follow contingent, recordkeeping norms is associated with lower marital satisfaction comes from studies by Murstein, Cerreto, and MacDonald (1977) and by Buunk and VanYperen (1991). Murstein et al. (1977) measured the “exchange orientation” of one member of a group of married couples with a scale including items such as, “If I do dishes three times a week, I expect my spouse to do them three times a week.” They also administered a marital adjustment scale to research participants. Among both men and women, an exchange orientation toward marriage was negatively correlated with marital adjustment. (We would note, however, that they did not find an analogous negative correlation between exchange orientation and satisfaction in friendships, perhaps because the friendships were weak ones.)

Buunk and VanYperen (1991) had individuals fill out an eight-item measure of exchange orientation and a Global Measure of Equity (see Walster et al., 1978). The latter measure asks, “Considering what you put into your relationship relative to what you get out of it and what your partner puts in compared to what he gets out of it, how does your relationship ‘stack up’?” Respondents could indicate that they were getting a much better or better deal, an equitable deal, or a much worse or worse deal than their partner. Buunk and VanYperen also measured satisfaction with the relationship with an eight-item Likert-type scale that measures the frequency with which the interaction with the partner in an intimate relationship is experienced as rewarding and not as aversive.

As these researchers expected, perceiving oneself to be over- or underbenefited relative to one’s spouse was linked with lower relationship satisfaction among those high in exchange orientation but not among those low in exchange orientation. More important for the present point, however, there was a main effect of being high in exchange orientation on marital satisfaction. Those high in exchange orientation reported substantially lower marital satisfaction than did those low in exchange orientation. They did so regardless of whether they reported being underbenefited, equitably benefited, or overbenefited (Buunk & VanYperen, 1991).

Can We Follow Contingent Rules Anyway?

Still another reason we believe that people do not keep track of inputs and calculate fairness on some sort of contingent basis in well-functioning close relationships is simply that following any contingent rule in relationships in which levels of interdependence are high is virtually impossible. Even to make a substantial effort to do so day to day and week to week would be so effortful as to be tremendously irritating and painful to the relationship members involved. Consider the impossibility of accurately keeping track of benefits first.

Think of the sheer number and variety of benefits that are likely to be given and received in an intimate relationship for example, between a husband and wife living together in the same home. Each day a very large number of household tasks (e.g., making beds, doing laundry, picking up clutter, preparing food, shopping for food, putting groceries away, vacuuming, dusting, taking the mail in, feeding pets, changing light bulbs and toilet paper, etc.) are done. So too are a variety of nonhousehold services (e.g., dropping a spouse off at work, picking up take-out food, dropping off dry cleaning, having something framed, visiting relatives, etc.). Then there are benefits that fall within the categories of verbal affection, physical affection, information, instructions, and goods that are given and received. Furthermore, things such as restrained behavioral impulses might be considered benefits. How in the world can two people in a relationship accurately track these things and still accomplish anything else in their lives? The answer is, we think, that they cannot.

To make matters worse, one must keep in mind that tracking the equality or equity of benefits given and benefits received involves far more than simply keeping track of what has been given by each member of a relationship. To compute equality or equality one must place values or weights on the diverse benefits given and received and compute the equality, equity, or evenness of repeated specific exchanges. What is taking the garbage out worth? Does it matter if it is cold and rainy outside? How does it compare with another simple service such as putting the laundry in the machine or unloading the dishwasher? Tougher yet, how does it compare with giving a hug (and does the hug get discounted because both people benefit)?

To push this even further, consider these questions. How does the ability and enjoyment of giving a benefit figure into the calculations? If one partner enjoys doing laundry and the other does not, is laundry done by the latter weighted higher than laundry done by the former? If one partner does not care if the living room is cluttered but the other one does, does it count at all if the latter person cleans up the clutter? These questions are difficult, and they probably seem silly. We suggest that the reason they may seem silly is precisely that people simply do not try to calculate these things in their day-to-day lives, primarily because in good times issues of fairness do not occur to them. Moreover, in times of more stress, when people may have some desire to compute such things, they realize the futility of trying to compute objective equality or equity across diverse domains of inputs and outcomes. (Later we address what we suspect they actually do in times of stress.)

Even If We Could Follow Contingent Norms, Do We Have Access to the Necessary Information?

Imagine that one did have the cognitive capacity to keep track of all benefits given and received in a relationship. Does one have access to all the relevant input? We do not think so. Again, consider a husband and wife who live together—a husband and wife who can surmount the obstacles to record keeping just discussed. We still think it would be an impossible task to track everything that ought to be tracked simply because each person has better access to contributions that he or she has made to the relationship than to contributions that the other has made for a number of reasons. The most straightforward reason is that many contributions one partner makes to the relationship are made in the absence of the other partner.

Picture the husband arriving home prior to the wife. He stops at the mailbox and brings the mail into the house. He throws out the junk and leaves the rest on the table. He notices that the cat has tipped over a plant and cleans up the mess. He listens to three solicitation messages left on the answering machine and deletes them. Although tired, he chats pleasantly when his mother-in-law calls in order to make her feel good and keep her company. He starts dinner. His wife arrives. She notices the mail on the table and the dinner cooking, but does she know anything about the other contributions to the relationship that her spouse has made? No, and he may well not mention them. The general point is that because of the lopsided accessibility of information about contributions to a relationship, there will always be a bias to perceive that the self has made more contributions than the partner has made.

Are Contingent Rules Ever Used in Close Relationships?

To recap, we argued that the ideal norm for giving and receiving benefits in close relationships (within an implicit cost boundary) is a need-based, or communal, norm. We further noted that when such relationships are functioning well, issues of fairness tend not to arise. This is not, however, to say that complaints and distress never arise. A need may be neglected, and the neglected person may become distressed and complain. Ideally, the partner responds to that distress and complaint in such a manner as to address the need at hand, soothe the partner, and maintain the relationship on an even, communal keel. However, perhaps the need will not be addressed. It is then, we contend, that processes leading to concerns about fairness may begin to unfold.

Imagine that a person neglects his or her partner’s needs; the latter complains, but the former does not respond by adequately addressing the need. Even then, we suspect, the situation may unfold in such a manner that issues of fairness do not arise. Specifically, sometimes the partner will respond with a benign interpretation of the behavior. For instance, that partner may respond by blaming unstable, situational causes rather than the partner (cf. Bradbury & Fincham, 1990), and the behavior may simply be tolerated. Rusbult et al. (1991) described this action as accommodation, generally, and as an instance of reacting with loyalty, more specifically.

For instance, consider a woman who lives far from her family of origin and misses them terribly. She tells her husband of her desire to visit them during their next vacation. He refuses, countering that he would rather take a relaxing trip, perhaps one to the beach. She then suggests that they could go for just a weekend, and he refuses again, saying that he really wants her to stay home and get some work done and that he really needs her company. In other words, he does not respond to her needs. In the face of this his wife may interpret his behavior benignly by attributing it to the situation (“He’s very stressed. It’s not that he doesn’t love me; he just needs to relax”). She may then behave constructively by continuing on with her own communal behavior (acting loyally). She may even go beyond benignly attributing her partner’s behavior to the nonstable, situational factors and actually connect her partner’s faults (as evidenced by the poor behavior) to virtues, as Murray and Holmes (1993) observed. For instance, his reluctance to visit relatives and his desire to be with her alone on vacation or at home might be taken as evidence of his love for her and of his sensible nature—he does not want to take too much on. In any case, she continues on, maintaining her faith in the overall communal nature of their relationship.

But sometimes spouses do not respond in such an accommodating manner or by connecting their partner’s faults to virtues. Instead, they may conclude that their partner really is not a good partner or that they themselves are not worthy of care. In such instances, people may well experience an inclination to switch to contingent rules of distributive justice, and they may actually do so. Doing so, we believe, is triggered by the judgment that one’s partner has not met one’s need combined with a judgment that this is due to a lack of true caring for the self. One might say that trust in the partner has evaporated. At such times, the adoption of a contingent distributive justice rule in place of a communal rule is likely to seem adaptive. It seems adaptive, we contend, because it is judged to be a more effective means of getting what one needs from one’s partner than is trusting that partner to be noncontingently responsive to one’s needs.

Consider once again the woman who lives far from her family of origin and misses them terribly. This time, after she suggests that they could go just for a weekend and he refuses again, saying that he really wants her to stay home and that he needs her company, she becomes increasingly distressed at her husband’s refusal to respond in any way to her needs. She may attribute his behavior to himself rather than to the situation (“He’s selfish”). Alternatively, or perhaps additionally, she may attribute his behavior to herself (“I’m not loveable”). His faults may also bring other faults to mind (“He’s selfish; he’s often inconsiderate”). He is really not very insightful or intelligent. In general, he is an embarrassment to be around.

In any case, the wife may conclude that the only way her husband is going to respond to her needs is if he must do so in order to receive benefits himself (a contingent, exchange perspective). Thus, she may counter his responses by thinking, “Well, OK, if that’s the way he’s going to be,” and saying, “Look, if you’re not willing to visit my family, then you certainly can’t expect me to go visit yours next May when we were planning on going. I’m only going to go if you do the same for me.”

This threat may well work in that the spouse agrees to go visit her family. Unfortunately, we propose, it works with some costs. Switching from a communal to an exchange norm sacrifices important things. First, the donor of a benefit will no longer be able to derive the same sense of nurturing the other. He or she must attribute at least part (or maybe all) of their motivation to their own selfish interests. Second, the recipient of the benefit no longer derives the same sense of being cared for and security from acquiring the benefit. He or she must attribute at least part (or maybe all) of the donor’s motivation to the donor’s own self-interest rather than to the donor’s sense of caring for them. Trust is also likely to deteriorate.

When Will People Switch?

We already suggested that switches from communal to exchange norms are likely to be triggered when a person feels that his or her needs have not been met. We have also suggested, however, that this will not always occur. Thus, an important question becomes when it will and will not occur. We have two answers to this question, one having to do with the situation in which a person finds him- or herself and one having to do with the personality of the person whose needs have been neglected and who is, therefore, vulnerable to switching.

The Situation Matters

Our first answer is straightforward. We predict that people will be more likely to switch from communal to exchange equality or equity norms when they perceive that their needs are being neglected. This may occur because a partner who has normally been quite responsive to the person’s needs ceases to be so responsive to that person’s needs. This could occur because the partner has become interested in someone or something else or because the partner is under considerable stress or is distracted from the partner’s needs. It also may occur because the person who needs help has experienced a large increase in needs that the partner cannot meet. If this is the case, and if the partner continues to neglect needs despite any attempts on the person’s part to rectify the situation, the person might switch to an exchange norm.

Of course, there are other options available to the person who has lost faith in the communal norm. The person could leave the relationship altogether or switch immediately to simply watching out for his or her own needs without adopting a norm such as equity or equality.

How are decisions between these options made? We can only speculate at this point, but it seems to us that certain variables that have long been discussed by interdependence theorists are relevant to making these decisions. If there are few barriers to leaving (i.e., in interdependence terms, if the person has good alternative options, such as being alone or forming alternative relationships), if investments in the relationship are low, and if there are few social or personal prescriptives to leaving, the person whose needs are being neglected might simply leave. Aswitch to contingent, recordkeeping norms might never take place. We suspect this often happens in friendships. If a friend neglects one’s needs, people usually have other friends (or potential friends) to whom they can turn. There are typically not great social or personal prescriptives against letting a friendship lapse, and investments in friendships tend to be lower than those in other close relationships (e.g., romantic relationships, marriages, or parent-child relationships).

On the other hand, sometimes there are considerable barriers to leaving a close relationship. Investments may be high, alternatives may not seem attractive, and there may be strong social and personal pressures working against a person’s leaving the relationship. We suspect that when such barriers are high, people whose needs have been seriously neglected will stay in the relationship but switch from adherence to a communal norm to adherence to a contingent record-keeping norm such as equity, equality, or exchange. This may happen in many marriages in which investments that cannot be recouped have been made (e.g., children, a joint house, financial success, joint friends), alternatives seem poor (being poorer, living alone, leaving the house), and strong prescriptions against leaving exist (one’s church or parents would disapprove). In such circumstances, the best option may seem to be to continue relationship but to switch the basis on which benefits are given in such a way that one feels more certain that one’s needs will be met. This may seem most workable even if one has to sacrifice a sense of being nurtured and of nurturing.

Individual Differences Matter

We believe that it is the situation that triggers people to switch from communal to contingent, record-keeping distributive justice norms, but we also believe that personality matters. People differ from one another in terms of their chronic tendencies to believe that others will be responsive to their needs and that they are worthy of such responsiveness. This has been a major theme in recent relationship literature. It is especially evident in the attachment theory and the empirical work that has been based on that theory. Secure individuals are assumed to view close others as likely to respond to their needs on a consistent basis, and they feel comfortable depending on others for support. Insecure people do not. However, attachment theorists are not the only ones who have emphasized differences in how people tend to view their partners. Others have talked about people differing in their chronic tendencies to trust other people in close relationships without necessarily referring to attachment theory (Holmes & Rempel, 1989), or about how chronic levels of self-esteem may relate to views of, and reactions to, close partners (Murray, Holmes, MacDonald, & Ellsworth, 1998). For our own part, we have discussed chronic individual differences in communal orientation, which refers to the tendency to respond to the needs of others and to expect others to respond to one’s own needs on a noncontingent basis (Clark et al., 1987).

We suspect that these chronic individual differences that people bring to their close relationships will be important determinants of switching from communal to exchange norms in the face of evidence that one’s partner is neglecting one’s needs. We suspect that almost everyone (regardless of attachment style, trust, self-esteem, or communal orientation) understands communal norms as we have discussed them. Moreover, we would assert that almost everyone believes that communal norms are ideal for friendships, romantic relationships, and marriages and that people start off such relationships following such norms. Indeed, it is by following such norms in the first place that people signal to potential partners that they want a friendship or romantic relationship with another person.

However, we also suspect that people who are insecure, have low trust in others, are low in self-esteem, or are low in chronic communal orientation (variables that we suspect cooccur) will be especially vulnerable to switching from a communal to an exchange norm in the face of real or imagined evidence that the other is neglecting their needs. They are the people, we assert, who react to the slightest evidence of such neglect with conclusions that the evidence indicates that the other is selfish and does not care for them or that they are unworthy of care. Further, we suggest that such conclusions, in turn, lead them to back away from the relationship. Alternatively (perhaps because they also are likely to perceive that they have fewer good alternatives than others do), these insecure individuals might be led to switch to a contingent, record-keeping norm such as equality, equity, or exchange as a basis for giving and receiving benefits in their relationship.

Evidence

The arguments we have just made suggest something that, to date, has not received attention in the distributive justice literature. Researchers in that tradition have typically advocated that there is one real rule that governs the giving and receiving of benefits within close relationships. Some suggest it is equality (Austin, 1980; Deutsch, 1975, 1985, for friendships); some suggest it is equity (Sabatelli & Cecil-Pigo, 1985; Utne et al., 1984; Walster et al., 1978); and some say it is a need-based rule (Deutsch, 1975, 1985, for family relationships; Lamm & Schwinger, 1980, 1983; Mills & Clark, 1982). Whatever rule they advocate, though, it has tended to be a single rule, and they have suggested that people in close relationships generally follow that rule. If a person does a good job following the particular rule, all is well. If the rule is violated, unhappiness results, and either the distress must be resolved or the relationship may end. We are suggesting something quite different.

We are suggesting that people in general start off their close relationships believing in a communal norm and doing their best to follow it. Such a norm requires mutual responsiveness to needs. However, it is inevitable that needs will be neglected. When this happens or when it is perceived to have happened, distress will occur, as we have argued. The distress, in turn, sets the stage for a possible switch to a contingent, record-keeping norm such as equity or exchange. Thus, it is likely that it is distress that—in most relationships some of the time and in some relationships very often—leads to record keeping. Such record keeping will, however, necessarily be retrospective at first.As such, it is very likely that it will be biased in such a manner as to result in evidence of inequity. Perceptions of inequity will, in turn, lead to judgments of unfairness. Then, in an iterative fashion, these perceptions will lead to further distress. Note that this is the reverse of what has typically been argued in the past, which is that record keeping and calculations of equity come first and that distress results when inequities are detected (Walster et al., 1978).

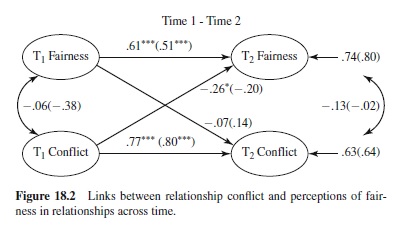

Is there any evidence for our proposal that distress precedes perception of unfairness in close relationships (rather than vice versa)? The answer is yes (Grote & Clark, 2001). In a recent study we tracked both conflict and perceptions of unfairness in a sample of about 200 married couples. These couples were enrolled in the study at a time when the wife was in the third trimester of her first pregnancy. Marital conflict (distress) was tapped at that time, again a few months after the baby was born, and a third time when the baby was about 1 year old. We also asked many questions about the division of household labor at all three points in time and about how fair the husband and wife felt that division of labor to be. (Notably, the division of labor was almost always judged to be unfair, with the wife performing more whether she stayed at home, worked part time or worked full time, and with both spouses agreeing that this was unfair.)

The longitudinal panel design of this study allowed us to conduct path analyses on the data in order to ascertain whether conflict at Time 1 predicted perceptions of unfairness at Time 2 (controlling for perceptions of unfairness at Time 1). Our theoretical position led us to the prediction that it would. We were also able to test whether perceptions of unfairness at Time 1 would predict conflict at Time 2 (controlling for conflict at Time 1). Traditional perspectives would lead to the prediction that it would. However, our theoretical perspective led us to predict that that would not necessarily be the case. That is, we believed that the division of labor could be inequitable and could be judged to be unfair when a social scientist came along and asked about it but still might not disrupt the relationship if both partners felt that their needs were being met and did not feel stressed.

The results, which are shown in Figure 18.2, were as we expected. Conflict at Time 1 (which we felt was indicative of situations in which at least one person was feeling that his or her needs were not being met) prospectively and significantly predicted perceptions of unfairness at Time 2 controlling for perceptions of unfairness at Time 1. Perceptions of unfairness at Time 1, however, were not significant prospective predictors of conflict at Time 2 controlling for perceptions of conflict at Time 1. This occurs, we assert, because in low-stress times when partners’ needs are being met (as we suspected was the case for most couples prior to the birth of an eagerly anticipated first child), people are not keeping track of inputs and outcomes day to day and are not calculating fairness. Whereas they can report on inequities in housework when a social scientist asks them to do so, we believe that most of our couples were not doing this on their own. That is why our measures of perceived unfairness did not predict conflict. In contrast, the early measures of conflict, we suspect, did pick up on those couples including at least one member who felt that his or her needs were being neglected. It is among these couples, we suspect, that record keeping (much of it retrospective and biased) emerged, resulting in perceptions of unfairness.

Once record keeping does emerge and unfairness is perceived, we have predicted that those perceptions of unfairness will increase unhappiness further. Evidence for this subsequent process emerged in the Grote and Clark data as well. Specifically, when changes in the patterns of data from Time 2 until Time 3 were examined, it was found that perceptions of unfairness at Time 2 (shortly after the baby had been born) until Time 3 (when the baby was about 1 year old) did significantly predict increases in conflict, controlling for conflict at Time 2. This occurred, we believe, because once couples were stressed and record keeping commenced, finding evidence of inequities increased distress still further. One interesting result was that conflict measured at Time 2 did not predict further increases in perceptions of unfairness as Time 3 (controlling for perceptions of unfairness at Time 2).

Thus, we have acquired and reported evidence consistent with the notion that the existence of inequities in a marriage will not necessarily lead to distress. We have also acquired and reported evidence consistent with the notions that distress might be what triggers contingent record keeping and perceptions of unfairness. We do not yet have hard empirical evidence that there are individual differences in people’s tendencies to feel that their needs have been neglected and, in turn, to switch from adherence to a communal norm to adherence to some sort of record keeping, contingent, distributive justice norm. However, we are currently collecting and beginning to analyze data relevant to just that question.

Permanent or Temporary Switches?

Afinal issue we wish to address in this research paper is whether the change will be permanent or temporary once people switch from a communal to a contingent, record-keeping norm for distributing benefits within their relationship. We propose that most such switches will be temporary. These changes will occur when a person is dissatisfied with how a relationship is going, wishes to ensure that his or her needs are met by the partner, and (not incidentally) wishes to signal his or her distress to the partner. Indeed, communicating displeasure may be just as important a motivator of the switch as is ensuring that one gets what one wants. Once the switch has been made and communicated, the protest function of having done so is largely accomplished. So, too, may the person have accomplished the short-term goal of having one immediate need addressed.

However, once a contingent, record-keeping distributive justice norm begins to be used, all the disadvantages of following such a norm will emerge. That is, record keeping will have to be done. It is tedious; it is virtually impossible to do competently; and given all the sorts of biases already discussed in this research paper, there will inevitably be disagreements over whether equity, equality, or fair exchange have been achieved. Moreover, the advantages of following a communal norm will evaporate. The recipient of benefits will not feel that the other cares for him orher, and the donor of benefits will not derive satisfaction for having nurtured a partner. These things combined with the strong societal norm that communal rules ought to characterize marriages and other close relationships will combine to push couples back to following a communal norm. Moreover, stresses in relationships themselves will often dissipate, and reminders of a partner’s true caring attitudes will reemerge. Thus, we would predict that couples will often bounce back to using communal norms.

On the other hand, there should also be cases when couples do not bounce back. Chronic neglect of at least one partner’s needs by the other may predict this. So too may either partner’s long-term, pessimistic views of the likelihood of the other being caring (and of the self being worthy of care) predict such a lack of resilience. These two things, in combination, may be especially likely to predict that a switch to contingent norms will be longer term. Such a switch, as we have already noted, is unlikely to constitute a satisfying solution. Therefore, we believe that it will likely be followed by a further switch to purely self-interested behavior or to the dissolution of the relationship. Whether the relationship persists long term (and perhaps happily), given the use of contingent record-keeping norms, or whether it ends will depend on the presence or absence of the sorts of barriers to leaving that interdependence theorists have discussed. That is, having poor alternatives, high investments, and feeling prescriptions against leaving are factors likely to keep couples together despite giving and receiving benefits on what we consider to be nonoptimal bases. Good alternatives, low investments, and low prescriptions to leaving are likely to predict relationship dissolution.

Conclusions

In this research paper we described what we believe to be the characteristics of a high-quality friendship, dating relationship, marriage, or family relationship. We suggested that quality ought not be defined in terms of stability, satisfaction, or conflict but rather in terms of the presence of interpersonal processes that facilitate the well-being of its members. We also suggested that members ought to agree implicitly on the degree of responsiveness to needs that is expected in the relationship and that relationships can go bad not only if responsiveness to needs is not present when expected but also if it is present when it is not called for.

Next we pointed out that viewing close relationships in this way suggests taking a new approach to understanding the use (and nonuse) of contingent, record-keeping distributive justice norms in intimate relationships. In well-functioning intimate relationships people should respond to one another’s needs in a noncontingent fashion as those needs arise. Record keeping should not be an issue, and fairness should not be discussed. Fairness simply should not be a salient issue for people in such relationships. (Of course, if some social scientist comes along and asks participants to judge the fairness of the giving and receiving of benefits in that relationship, we have no doubt that members will come up with such ratings.We just do not think they do this spontaneously on their own.) Members of such relationships appear to be following a communal rule, and we believe that following such a rule promotes a sense of intimacy, security, and well-being in the relationship.

However, we argued further, record keeping may become an issue in relationships that members would like to see operate on a communal basis. It becomes an issue if and when needs are perceived to have been neglected and attributions of a lack of caring are made. In such cases, partners in a relationship may switch to record-keeping norms such as exchange, equity, or equality in an effort to ensure that their needs are met. Once this is done, it is very likely that unfairness will be perceived (whether it objectively exists or not), and distress is likely to increase. However, we do believe that many couples are resilient and will “bounce back” to following communal norms with time. Others will not be resilient, and members of such relationships will continue, often times unhappily, to use record-keeping rules to give and receive benefits or even to rely on pure self-interest. Depending on barriers to exiting the relationship, it may or may not dissolve.

Bibliography:

- Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, C., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Austin, W. (1980). Friendship and fairness: Effects of type of relationship and task performance on choice of distribution rules. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 6, 402–408.

- Bradbury, T. N., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Attributions in marriage: Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 3–33.

- Buunk, B. P., & Van Yperen, N. W. (1991). Referential comparisons, relational comparisons, and exchange orientation: Their relation to marital satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 709–717.

- Cate, R. M., Lloyd, S. A., & Henton, J. M. (1985). The effect of equity, equality and reward level on the stability of students’ premarital relationships. Journal of Social Psychology, 125, 175–725.

- Chaiken, A. L., & Derlega, V. J. (1974). Liking for the norm-breaker in self-disclosure. Journal of Personality, 42, 117–129.

- Christensen, L., & Wallace, L. (1976). Perceptual accuracy as a variable in marital adjustment. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 2, 130–136.

- Clark, M. S., Fitness, J., & Brissette, I. (2001). Understanding people’s perceptions of relationships is crucial to understanding their emotional lives. In G. Fletcher & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (pp. 253–278). London: Blackwell.

- Clark, M. S. & Grote, N. K. (2001). Manuscript in preparation.

- Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (1979). Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 12–24.

- Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (1993). The difference between communal and exchange relationships: What it is and is not. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 684–691.

- Clark, M. S., Mills, J., & Powell, M. C. (1986). Keeping track of needs in communal and exchange relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 333–338.

- Clark, M. S., Ouellette, R., Powell, M. C., & Milberg, S. (1987). Recipient’s mood, relationship type and helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 94–103.

- Clark, M. S., & Waddell, B. (1983). Effects of moods on thoughts about helping, attraction, and information acquisition. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46, 31–35.

- Collins, N. L., & Allard, L. M. (2001). Cognitive representations of attachment: The content and function of working models. In G. J. O. Fletcher & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (pp. 60–85). London: Blackwell.

- Collins, N. L., & Feeney, B. C. (2000). Asafe haven: An attachment theory perspective on support seeking and caregiving in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 1053–1073.

- Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic view. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 457–475.

- Cox, C. L., Wesler, M. O., Rusbult, C. E., & Gaines, S. O. (1997). Prescriptive support and commitment processes in close relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60, 79–90.

- Deutsch, M. (1975). Equity, equality and need: What determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues, 31, 137–148.

- Deutsch, M. (1985). Distributive justice: A socio-psychological perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Feeney, J. A. (1995). Adult attachment and emotional control. Personal Relationships, 2, 143–159.

- Feeney, J. A. (1999). Adult attachment, emotional control, and marital satisfaction. Personal Relationships, 6, 169–185.

- Finkel, E. J., & Campbell, W. K. (2001). Self-control and accomodation in close relationships: An interdependence analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 263–277.

- Fitzpatrick, J., & Sollie, D. L. (1999). Influence of individual and interpersonal factors on satisfaction and stability in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 6, 337–350.

- Gottman, J. M. (1979). Marital interaction: Experimental investigations. New York: Academic Press.

- Gottman, J. M., & Porterfield, A. L. (1981). Communicative competence in the nonverbal behavior of married couples. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 43, 817–824.

- Grote, N. K., & Clark, M. S. (1998). Distributive justice norms and family work: What is perceived as ideal, what is applied, and what predicts perceived fairness? Social Justice Research, 11, 243–269.

- Grote, N. K., & Clark, M. S. (2001). Does conflict drive perceptions of unfairness or do perceptions of unfairness drive conflict? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 2, 281–293.

- Guthrie, D. M., & Noller, P. (1988). Married couples’ perceptions of one another in emotional situations. In P. Noller & M. A. Fitzpatrick (Eds.), Perspectives on marital interaction (pp. 153– 181). Cleveland, OH: Multilingual Matters.

- Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

- Holmes, J. G., & Rempel, K. (1989). Trust in close relationships. In C. Hendrick (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology: Vol. 10. Close relationships (pp. 187–219). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Howe, N., Aquan-Assee, J., Bukowski, W. M., Rinaldi, C. M., & Lenoux, P. M. (2000). Sibling self-disclosure in early adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 653–671.

- Huston, T. L., & Burgess, T. L. (1979). Social exchange in developing relations: An overview. In R. Burgess & T. Huston (Eds.), Social exchange in developing relations. New York: Academic Press.

- Ickes, W. (1993). Empathic accuracy. Journal of Personality, 61, 587–610.

- Johnson, D. J., & Rusbult, C. E. (1989). Resisting temptation: Devaluation of alternative partners as a means of maintaining commitment in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 967–980.

- Kaplan, K. J., Firestone, I. J., Degnore, R., & Morre, M. (1974). Gradients of attraction as a function of disclosure probe intimacy and setting formality: On distinguishing attitude oscillation from attitude change—Study one. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30, 638–646.

- Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley.

- Lamm, H., & Schwinger, T. (1980). Norms concerning distributive justice: Are needs taken into consideration in allocation decisions? Social Psychology Quarterly, 43, 425–429.

- Lamm, H., & Schwinger, T. (1983). Need consideration in allocation decisions: Is it just? Journal of Social Psychology, 119, 205–209.

- McCullough, M. E. (2000). Forgiveness as human strength: Theory, measurement, and links to well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 43–55.

- Meeks, B. S., Hendrick, S. S., & Hendrick, C. (1998). Communication, love and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15, 755–773.

- Miller, L. C., Berg, J., & Archer, R. L. (1983). Openers: Individuals who elicit intimate self-disclosure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 1234–1244.

- Mills, J., & Clark, M. S. (1982). Exchange and communal relationships. In L. Wheeler (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology (pp. 121–144). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Mills, J., & Clark, M. S. (1986). Communications that should lead to perceived exploitation in communal and exchange relationships. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4, 225–234.

- Murray, S. L., & Holmes, J. G. (1993). Seeing virtues in faults: Negativity of the transformation of interpersonal narratives in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 707–722.

- Murray, S. L., & Holmes, J. G. (1997). Aleap of faith? Positive illusions in romantic relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 586–604.

- Murray, S. L., Holmes, J .G., Dolderman, D., Griffin, D. W. (2000). What the motivated mind sees: Comparing friends’ perspectives to married partners’ views of each other. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

- Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. (1996a). The benefits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 79–98.

- Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. (1996b). The selffulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationships: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1155–1180.

- Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., MacDonald, G., & Ellsworth, P. (1998). Through the looking glass darkly? When self-doubts turn into relationship insecurities. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1459–1480.

- Murstein, B. I., Cerreto, M., & MacDonald, M. G. (1977). A theory and investigation of the effect of exchange-orientation on marriage and friendships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 39, 543–548.

- Noller, P. (1980). Misunderstandings in marital communication: A study of couples’ nonverbal communication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1135–1148.

- Noller, P. (1981). Gender and marital adjustment level differences in decoding messages from spouses and strangers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 272–278.

- Purvis, J. A., Dabbs, J. M., & Hopper, C. H. (1984). The “Opener”: Skilled user of facial expression and speech pattern. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 61–66.

- Reis, H. T., & Patrick, B. C. (1996). Attachment and intimacy: Component processes. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press.

- Reis, H. T., & Shaver, P. (1988). Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In S. W. Duck (Ed.), Handbook of personal relationships (pp. 367–391). New York: Wiley.

- Rusbult, C. E. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 101–117.

- Rusbult, C. E., Arriaga, X. B., & Agnew, C. R. (2001). Interdependence in close relationships. In G. Fletcher & M. S. Clark (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: Interpersonal processes (pp. 359–387). London: Blackwell.

- Rusbult, C. E., & Martz, J. M. (1995). Remaining in an abusive relationship: An investment model analysis of nonvoluntary commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 558–571.

- Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (1996). Interdependence processes. In E. T. Higgins & A. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press.

- Rusbult, C. E., Verette, J., Whitney, G., Slovik, L., & Lipkus, I. (1991). Accomodation processes in close relationships: Theory and preliminary empirical evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 53–78.

- Sabatelli, R. M., & Cecil-Pigo, E. F. (1985). Relational interdependence and commitment in marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 47, 931–937.

- Simpson, J. A., Gangestad, S. W., & Lerma, M. (1990). Perception of physical attractiveness: Mechanisms involved in the maintenance of romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1192–1201.

- Simpson, J. A., & Rholes, W. S. (1998). Attachment theory and close relationships. New York: Guilford Press.

- Simpson, J. A., Rholes, W. S., & Nelligan, J. S. (1992). Support seeking and support giving within couples in an anxietyprovoking situation: The role of attachment styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 434–446.

- Sprecher, S. (1986). The relation between inequity and emotions in close relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51, 318–328.

- Utne, M. K., Hatfield, E., Traupmann, J., & Greenberger, D. (1984). Equity, marital satisfaction, and stability. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 1, 323–332.

- Van Lange, P. A. M., & Rusbult, C. E. (1995). My relationship is better than—and not as bad as—yours is: The perception of superiority in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 32–44.

- Vittengl, J. R., & Holt, C. S. (2000). Getting acquainted: The relationship of self-disclosure and social attraction to positive affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 17, 53–66.

- Walster, E., Walster, G. W., & Berscheid, E. (1978). Equity: Theory and research. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Williamson, G. M., & Clark, M. S. (1989). Providing help and desired relationship type as determinants of changes in moods and self-evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 722–734.

- Williamson, G. M., & Clark, M. S. (1992). Impact of desired relationship type on affective reactions to choosing and being required to help. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 10–18.

- Williamson, G. M., Pegalis, L., Behan, A., & Clark, M. S. (1996). Affective consequences of refusing to help in communal and exchange relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 34–47.