View sample Schemas, Frames, And Scripts In Cognitive Psychology Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

The terms ‘schema,’ ‘frame,’ and ‘script’ are all used to refer to a generic mental representation of a concept, event, or activity. For example, people have a generic representation of a visit to the dentist office that includes a waiting room, an examining room, dental equipment, and a standard sequence of events in one’s experience at the dentist. Differences in how each of the three terms, schema, frame, and script, are used reflect the various disciplines that have contributed to an understanding of how such generic representations are used to facilitate ongoing information processing. This research paper will provide a brief family history of the intellectual ancestry of modern views of generic knowledge structures as well as an explanation of how such knowledge influences mental processes.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Early Development Of The ‘Schema’ Concept

The term ‘schema’ was already in prominent use in the writings of psychologists and neurologists by the early part of the twentieth century (e.g., Bartlett 1932, Head 1920, see also Piaget’s Theory of Child Development). Though the idea that our behavior is guided by schemata (the traditional plural form of schema) was fairly widespread, the use of the term ‘schema’ was seldom well defined. Nevertheless, the various uses of the term were reminiscent of its use by the eighteenth century philosopher Immanuel Kant. In his influential treatise Critique of Pure Reason, first published in 1781, Kant wrestled with the question of whether all knowledge is dependent on sensory experience or whether there exists a priori knowledge, which presumably would consist of elementary concepts, such as space and time, necessary for making sense of the world. Kant believed that we depend both on our knowledge gained from sensory experience and a priori knowledge, and that we use a generic form of knowledge, schemata, to mediate between sensory-based and a priori knowledge.

Unlike today, when the idea of a schema is most often invoked for large-scale structured knowledge, Kant used the term in reference to more basic concepts. In Critique of Pure Reason he wrote: ‘In truth, it is not images of objects, but schemata, which lie at the foundation of our pure sensuous conceptions. No image could ever be adequate to our conception of triangles in general … The schema of a triangle can exist nowhere else than in thought and it indicates a rule of the synthesis of the imagination in regard to pure figures in space.’ The key idea captured by Kant was that people need mental representations that are typical of a class of objects or events so that we can respond to the core similarities across different stimuli of the same class.

The basic notion that our experience of the world is filtered through generic representations was also at the heart of Sir Frederic Bartlett’s use of the term ‘schema.’ Bartlett’s studies of memory, described in his classic book published in 1932, presaged the rise of schematheoretic views of memory and text comprehension in the 1970s and 1980s. In his most influential series of studies, Bartlett asked people to read and retell folktales from unfamiliar cultures. Because they lacked the background knowledge that rendered the folktales coherent from the perspective of the culture of origin, the participants in Bartlett’s studies tended to conventionalize the stories by adding connectives and explanatory concepts that fit the reader’s own world view. The changes were often quite radical, particularly when the story was recalled after a substantial delay. For example, in some cases the reader gave the story a rather conventional moral consistent with more familiar folktales.

Bartlett interpreted these data as indicating that: ‘Remembering is not the re-excitation of innumerable fixed, lifeless, and fragmentary traces’ (p. 213). Instead, he argued, memory for a particular stimulus is reconstructed based on both the stimulus itself and on a relevant schema. By schema, Bartlett meant a ‘whole active mass of organised past reactions or experience.’ Thus, if a person’s general knowledge of folktales includes the idea that such tales end with an explicit moral, then in reconstructing an unfamiliar folktale the person is likely to elaborate the original stimulus by adding a moral that appears relevant.

Although Bartlett made a promising start on under- standing memory for complex naturalistic stimuli, his work was largely ignored for the next 40 years, particularly in the United States where researchers focused on much more simplified learning paradigms from a behavioral perspective. Then, interest in schemata returned as researchers in the newly developed fields of cognitive psychology and artificial intelligence attempted to study and to simulate dis- course comprehension and memory.

2. The Rediscovery Of Schemata

Interest in schemata as explanatory constructs returned to psychology as a number of memory re- searchers demonstrated that background knowledge can strongly influence the recall and recognition of text. For example, consider the following passage: ‘The procedure is actually quite simple. First, you arrange items into different groups. Of course, one pile may be sufficient, depending on how much there is to do. If you have to go somewhere else due to lack of facilities that is the next step; otherwise, you are pretty well set.’ This excerpt, from a passage used by Bransford and Johnson (1972), is very difficult to understand and recall unless the reader has an organizing schema for the information. So, readers who are supplied with the appropriate title, Washing Clothes, are able to recall the passage much more effectively than readers who are not given the title.

Although the early 1970s witnessed a great number of clear demonstrations that previous knowledge shapes comprehension and memory, progress on specifying exactly how background knowledge becomes integrated with new information continued to be hampered by the vagueness of the schema concept. Fortunately, at this same time, researchers in artificial intelligence (AI) identified the issue of background knowledge as central to simulations of text processing. Owing to the notorious inability of computers to deal with vague notions, the AI researchers had to be explicit in their accounts of how background knowledge is employed in comprehension. A remarkable cross-fertilization occurred between psychology and AI that encouraged the development and testing of hypotheses about the representation and use of schematic knowledge.

2.1 Schema Theory In AI Research: Frames And Scripts

Although many researchers in the nascent state of AI research in 1970s were unconcerned with potential connections to psychology, several pioneers in AI research noted the mutual relevance of the two fields early on. In particular, Marvin Minsky and Roger Schank developed formalizations of schema-theoretic approaches that were both affected by, and greatly affected, research in cognitive psychology.

One of the core concepts from AI that was quickly adopted by cognitive psychologists was the notion of a frame. Minsky (1975) proposed that our experiences of familiar events and situations are represented in a generic way as frames that contain slots. Each slot corresponds to some expected element of the situation. One of the ways that Minsky illustrated what he meant by a frame was in reference to a job application form. A frame, like an application, has certain general domains of information being sought and leaves blanks for specific information to be filled in. As another example, someone who walks into the office of a university professor could activate a frame for a generic professor’s office that would help orient the person to the situation and allow for easy identification of its elements. So, a person would expect to see a desk and chair, a bookshelf with lots of books, and, these days at least, a computer. An important part of Minsky’s frame idea is that the slots of a frame are filled with default values if no specific information from the context is provided (or noticed). Thus, even if the person didn’t actually see a computer in the professor’s office, he or she might later believe one was there because computer would be a default value that filled an equipment slot in the office frame (see Brewer and Treyens 1981 for relevant empirical evidence).

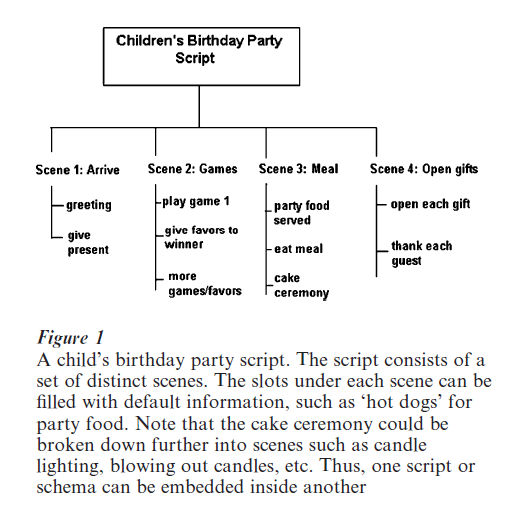

The idea that generic knowledge structures contain slots with default values was also a central part of Roger Schank’s work on scripts. Scripts are generic representations of common social situations such as going to the doctor, having dinner at a restaurant, or attending a party (Fig. 1). Teamed with a social psychologist, Robert Abelson, Schank developed computer simulations of understanding stories involving such social situations.

The motivation for the development of the script concept was Schank’s observation that people must be able to make a large number of inferences quite automatically in order to comprehend discourse. This can be true even when the discourse consists of a relatively simple pair of sentences:

Q: So, would you like to get some dinner?

A: Oh, I just had some pizza a bit ago.

Even though the question is not explicitly answered, a reader of these two sentences readily understands that the dinner invitation was declined. Note that the interpretation of this exchange is more elaborate if the reader knows that it occurred between a young man and a young woman who met at some social event and had a lengthy conversation. In this context, a script for asking someone on a date may be invoked and the answer is interpreted as a clear ‘brush off.’

Thus, a common feature of the AI work on frames and scripts in simulations of natural language understanding was that inferences play a key role. Furthermore, these researchers provided formal descriptions of generic knowledge structures that could be used to generate the inferences necessary to comprehension. Both AI researchers and cognitive psychologists of the time recognized that such knowledge structures captured the ideas implicit in Bartlett’s more vague notion of a schema. The stage was set to determine whether frames and scripts were useful descriptors for the knowledge that people actually use when processing information.

2.2 Empirical Support For Schema Theory

If people’s comprehension and memory processes are based on retrieving generic knowledge structures and, as necessary, filling slots of those knowledge structures with default values, then several predictions follow. First, people with similar experiences of common situations and events will have similar schemata represented in memory. Second, as people retrieve such schemata during processing, they will make inferences that go beyond directly stated information. Third, in many cases, particularly when processing is guided by a script-like structure, people will have expectations about not only the content of a situation but also the sequence of events.

Cognitive psychologists obtained empirical support for each of these predictions. For example, Bower et al. (1979) conducted a series of experiments on people’s generation of, and use of, scripts for common events like going to a nice restaurant, attending a lecture, or visiting the doctor. They found high agreement on the actions that take place in each situation and on the ordering. Moreover, there was good agreement on the major clusters of actions, or scenes, within each script. Consistent with the predictions of schema theory, when people read stories based on a script, their recall of the story tended to include actions from the script that were not actually mentioned in the story. Bower et al. (1979) also used some passages in which an action from a script was explicitly mentioned but out of its usual order in the script. In their recall of such a passage, people tended to recall the action of interest in its canonical position rather than in its actual position in the passage.

Cognitive psychologists interested in discourse processing further extended the idea of a schema capturing a sequence of events by proposing that during story comprehension people make use of a story grammar. A story grammar is a schema that specifies the abstract organization of the parts of a story. So, at the highest level a story consists of a setting and one or more episodes. An episode consists of an event that presents a protagonist with an obstacle to be overcome. The protagonist then acts on a goal formulated to overcome the obstacle. That action then elicits reactions that may or may not accomplish the goal. Using such a scheme, each idea in a story can be mapped onto a hierarchical structure that represents the relationship among the ideas (e.g., Mandler 1984). We can use story grammars to predict people’s sentence reading times and recall because the higher an idea is in the hierarchy, the longer the reading time and the better the memory for that idea.

Thus, the body of research that cognitive psychologists generated in the 1970s and early 1980s supported the notion that data structures like frames and scripts held promise for capturing interesting aspects of human information processing. Nevertheless, it soon became clear that modifications of the whole notion of a schema were necessary in order to account for people’s flexibility in comprehension and memory processing.

3. Schema Theory Revised: The New Synthesis

Certainly, information in a text or the context of an actual event could serve as a cue to trigger a relevant script. But what about situations that are more novel and no existing script is triggered? At best, human information processing can only sometimes be guided by large-scale schematic structures. Traditionally, schema theorists have tended to view schema application as distinct from the processes involved in building up schemata in the first place. So, people might use a relevant schema whenever possible, but when no relevant schema is triggered another set of processes are initiated that are responsible for constructing new schemata.

More recently, however, an alternative view of schemata has been developed, again with contributions both from AI and cognitive psychology. This newer approach places schematic processing at one end of a continuum in which processing varies from data driven to conceptually driven. Data-driven (also known as bottom-up) processing means that the analysis of a stimulus is not appreciably influenced by prior knowledge. In the case of text comprehension, this would mean that the mental representation of a text would stick closely to information that was directly stated. Conceptually driven (also known as top-down) processing means that the analysis of a stimulus is guided by pre-existing knowledge, as, for example, described by traditional schema theory. In the case of text comprehension, this would mean that the reader makes many elaborative inferences that go beyond the information explicitly stated in the text. In many cases, processing will be an intermediate point on the continuum so that there is a modest conceptually driven influence by pre-existing knowledge structures.

This more recent view of schemata has been called schema assembly theory. The central idea of this view is that a schema, in the sense of a framework guiding our interpretation of a situation or event, is always constructed on the spot based on the current context. Situations vary in how much background knowledge is readily available, so sometimes a great deal of related information is accessed that can guide processing and at other times very little of such background knowledge is available. In these cases we process new information in a data-driven fashion.

This new view of schemata was synthesized from work in AI and cognitive psychology as researchers realized the need to incorporate a more dynamic view of the memory system into models of knowledgebased processing. For example, AI programs based on scripts performed poorly when confronted with the kinds of script variations and exceptions seen in the ‘real world.’ Accordingly, Schank (1982) began to develop systems in which appropriate script-like structures were built to fit the specific context rather than just retrieved as a precomplied structure. Therefore, different possible restaurant subscenes could be pulled together in an ad hoc fashion based on both background knowledge and current input. In short, Schank’s simulations became less conceptually driven in their operation. Likewise, cognitive psychologists, confronted with empirical data that was problematic for traditional schema theories, have moved to a more dynamic view. There were two main sets of empirical findings that motivated cognitive psychologists to make these changes.

First, it became clear that people’s processing of discourse was not as conceptually driven as classic schema theories proposed. In particular, making elaborative inferences that go beyond information directly stated in the text is more restricted than originally believed. People may be quite elaborative when reconstructing a memory that is filled with gaps, but when tested for inference making concurrent with sentence processing, people’s inference generation is modest. For example, according to the classic view of schemata, a passage about someone digging a hole to bury a box of jewels should elicit an inference about the instrument used in the digging. The default value for such an instrument would probably be a shovel. Yet, when people are tested for whether the concept of shovel is primed in memory by such a passage (for example, by examining whether the passage speeds up naming time for the word ‘shovel’), the data suggest that people do not spontaneously infer instruments for actions. Some kinds of inferences are made, such as connections between goals and actions or filling in some general terms with more concrete instances, but inference making is clearly more restricted than researchers believed in the early days after the re- discovery of schemata (e.g., Graesser and Bower 1990, Graesser et al. 1997).

Second, it is not always the case that what we remember from some episode or from a text is based largely on pre-existing knowledge. As Walter Kintsch has shown, people appear to form not one, but three memories as they read a text: a short-lived representation of the exact wording, a more durable representation that captures a paraphrase of the text, and a situation model that represents what was described by the text, rather than the text itself (e.g., Kintsch 1988). It is this third type of representation that is strongly influenced by available schemata. However, whether or not a situation model is formed during comprehension depends on not only the availability of relevant chunks of knowledge, but also the goals of the reader (Memory for Meaning and Surface Memory; Situation Model: Psychological ).

Thus, background knowledge can affect processing of new information in the way described by schema theories, but our processing represents a more careful balance of conceptually-driven and data-driven processes than claimed by traditional schema theories. Moreover, the relative contribution of background knowledge to understanding varies with the context, especially the type of text and the goal of the reader.

To accommodate more flexibility in the use of the knowledge base, one important trend in research on schemata has been to incorporate schemata into connectionist models. In connectionist models the representation of a concept is distributed over a network of units. The core idea is that concepts, which are really repeatable patterns of activity among a set of units, are associated with varying strengths. Some concepts are so often associated with other particular concepts that activating one automatically entails activating another. However, in most cases the associations are somewhat weaker, so that activating one concept may make another more accessible if needed. Such a system can function in a more top-down manner or a more bottom-up manner depending on the circumstances. To rephrase this idea in terms of traditional schema theoretic concepts, some slots are available but they need not be filled with particular default values if the context does not require it. Thus, the particular configuration of the schema that is used depends to a large extent on the processing situation.

In closing, it is important to note that the success that researchers in cognitive psychology and AI have had in delineating the content of schemata and in determining when such background knowledge influences ongoing processing has had an important influence on many other ideas in psychology. The schema concept has become a critical one in clinical psychology, for example in cognitive theories of depression, and in social psychology, for example in understanding the influence of stereotypes on person perception (e.g., Hilton and von Hipple 1996). It remains to be seen whether the concept of a schema becomes as dynamic in these areas of study as it has in cognitive psychology.

Bibliography:

- Bartlett F C 1932 Remembering. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Bower G H, Black J B, Turner T J 1979 Scripts in memory for text. Cognitive Psychology 11: 177–220

- Bransford J D, Johnson M K 1972 Contextual prerequisites for understanding: A constructive versus interpretive approach. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior 11: 717–26

- Brewer W F, Treyens J C 1981 Role of schemata in memory for places. Cognitive Psychology 13: 207–30

- Graesser A C, Bower G H (eds.) 1990 Inferences and Text Comprehension: The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, Vol. 25

- Graesser A C, Millis K K, Zwaan R A 1997 Discourse comprehension. Annual Review of Psychology 48: 163–89

- Head H 1920 Studies in Neurology. Oxford University Press, London

- Hilton J L, von Hipple W 1996 Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology 47: 237–71

- Kant I 1958 Critique of Pure Reason, trans. by N. K. Smith. Modern Library, New York. Originally published in 1781

- Kintsch W 1988 The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension: A construction-integration model. Psychological Review 95: 163–82

- Mandler J M 1984 Stories, Scripts, and Scenes: Aspects of Schema Theory. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

- Minsky M 1975 A framework for representing knowledge. In: Winston P H (ed.) The Psychology of Computer Vision. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Schank R C 1982 Dynamic Memory: A Theory of Reminding and Learning in Computers and People. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Schank R C, Abelson R P 1977 Scripts, Plans, Goals, and Understanding. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

- Whitney P, Budd D, Bramucci R S, Crane R S 1995 On babies, bath water, and schemata: A reconsideration of top-down processes in comprehension. Discourse Process 20: 135–66