Sample Cognitive Psychology Of Group Decision Making Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

A group is a set of three or more persons who engage in joint activity directed at a common goal. For many groups, the goal is to make a decision. For other groups, the goal is achievement of a political, social, educational, or recreational objective. Regardless of their overall purpose, every group must make decisions so that member’s actions are coordinated, and directed toward the common objective. This research paper presents major developments in the understanding of the cognitive processes involved in group decision making. It begins with a description of the forces leading to the current importance of group decision making, and proceeds to explain how the cognitive processes in decision making groups can be understood with a social information processing model. Next, some of the conceptual and methodological problems surrounding group decision making theory and research are covered. The theme throughout this discussion concerns differences among group members in terms of their information, beliefs, and decision preferences. The significance of two recent advances in addressing differences among group members, the Judge Advisor System and Information Sharing paradigms, is explained.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Groups As Information Processors

Group decision making has become increasingly important in the world of work for many reasons. One is that a greater proportion of jobs now involve cognitive work, so just as individual workers shifted from physical to cognitive work, so did groups. Another force promoting the use of groups is the effort to increase representation and participation in organizational and societal decision making. Decisions that might have once been dictated by an authority are now made by a group representing various levels and segments of the population. Much of the current group research occurs in the context of organizational theory and practice (Sanna and Parks 1997)

The growth in the practice of using groups for decision making has been accompanied by a similar growth in the study of cognition in groups. The benefits of this research extend to all groups because all groups, regardless of their purpose, are dependent on cognitive processes for functioning. Simply put, people must coordinate their individual processes of attention, reasoning, judgment, memory, etc. during interaction in order to achieve their common goal. Group decisions are essential to coordination, and occur at many points during interaction. A group must choose its goal and the nature of the process that will be used to achieve it, select information deemed relevant, and integrate information, beliefs, etc. to determine the group’s course of action.

The influence of ‘real-world’ practice is evident by the efforts at realism in modern group decision making research. Whereas early group research used games, trivial and ‘eureka’ decision problems, research tasks now capture such essential features of real decisions as the inability to know, with certainty, the quality of the decision at the time it is made. Motivational issues are taken more seriously by, for example, using incentives for making good decisions to reflect better the consequences facing persons in decision making groups. Other advances in group decision making research are the use of ongoing groups, and the study of interactions using technology (email, videoconferencing, etc.).

Part of the current scientific activity pertaining to cognitive processes in groups can be traced to the recent growth of cognitive psychology and the birth of social cognition (Fiske 1992), a subdiscipline of psychology devoted to the study of cognition about social objects. Advances in these areas, combined with the increased prevalence of groups engaged in decision-making tasks, led to the modern view of conceptualizing groups as information processors. As described by Hinsz et al. (1997), key leaders in this development, the information processing approach to groups emphasizes the social processing of information, thereby integrating the group decision making and social cognition research approaches. In the social information processing view, groups exchange ideas, information, resources, strategies, etc. in the service of a processing objective. Research is directed at understanding attention, encoding, processing, storage, retrieval, feedback, and response processes in groups. Although recent group research tends to be guided by an individual-level information processing model, group and individual level processing are not assumed to be identical, and a pervasive research agenda is to understand the qualitative and quantitative differences between individual and group processing.

A primary difference between individual and group decision making arises from the greater complexity of group level processing of information, that is, group decision making requires coordination of individual members’ cognitive processes and communication of the outputs of these processes. For example, consider how the memory problem in groups requires development of common strategies for transactive memory (Wegner 1987), a shared representation of the organization of information over members. It is through transactive memory that groups are able to identify and use the unique information that members previously knew or are able to recall from group interactions. Further, groups have more complex processes because they have a number of unique problems from which individual performers are free. At the start, group members face social uncertainty about the other group members. This refers to an inability to predict the behavior of other persons, making it difficult to know the extent to which they are willing or able to work toward the group goal. Group members may have different ideas about what the group goal is or should be. If so, it is necessary to negotiate them before purposeful interaction can occur. At any point in time, groups can have social goals that detract attention, time, and efforts from the task of making a decision. Even if all members are clearly focused on a single objective directly related to their decision problem, they are likely to have differences in information, beliefs, and preferences that need to be integrated in order to reach that objective.

2. Levels Of Behavior In Groups

Despite the differences between individual and social information processing, it is sometimes possible to apply ‘individual’ cognitive constructs at the group level. Consider the case of human judgment. Judgment is the location of an object in an abstract representation such as a scale from one to nine, or a set of categories. An example of judgment in group decision making is a committee’s recommendation for a salary offer. On occasion, group members’ independent judgments may agree closely enough for the purpose at hand. But often, group members have cognitive conflict, that is, differences in beliefs. In some cases, groups may begin with varying judgments but end the task with a consensus group judgment of the amount. Yet, in other circumstances, members will adhere to discrepant judgments, and the judgment for the group must be a compromise such as the central tendency of the members’ judgments. Then an accurate picture of the group’s judgment needs to include some indicators of the variation in the members’ judgments. The problem is similar for cognitive tasks with discrete outcomes, such as deciding to uphold or overturn a law. When all are in agreement, there can be a group determination; if not, there can be only majority and minority member opinions. In general, we can describe members’ cognitions at the group level if observations of the members of a group are indistinguishable, that is, every group member provides a response identical to that of every other group member. Under such conditions, we can speak about group goals, group confidence, group memory, and so forth. Otherwise, it is necessary to represent the diversity of group members’ cognitions, with or without information on the cognitive value for the average or majority.

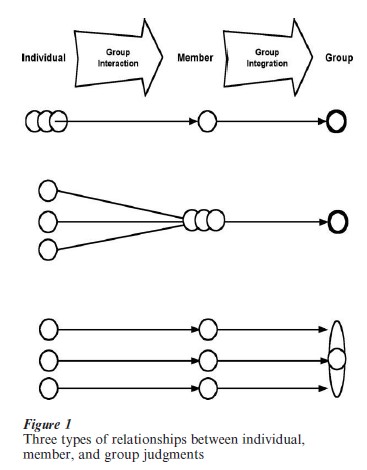

Figure 1 illustrates the distinction between the application of the cognitive construct of judgment to individuals, group members, and the group. Prior to interaction, there are three independent individual judgments representing individual information processing. These are similar in the first case, but different in the bottom two cases. These individual judgments or the beliefs surrounding them may be discussed during group interaction. Group interaction allows for social influence processes to transform the initial individual judgments into revised member judgments. Thus, the term ‘member’ is used to refer to individual members’ judgments during or following group interaction to distinguish these judgments from the initial individual judgment, whether or not they have changed. In the first case, members learn that they are in agreement on a single judgment that becomes the consensus group judgment. Member judgments have become similar in the second case, but not the third. As in the first case, the integration of member judgments into a single group judgment is straightforward in the second case. But in the third case shown at the bottom of the figure, there is no consensus group judgment, only an average judgment for the group. There may be no alternative but to use this average judgment to represent the group judgment. But an accurate picture of the group’s judgment must include the persistent differences among member judgments.

3. Problems In Conceptualizing Groups

The study of cognition in decision making groups extends to many aspects of the groups behavior. In practice, groups are comprised of individuals who can have considerable cognitive conflict in their processing of information relevant to their interactions and objectives, that is, the various persons in a group may have different schemas or frames for the problem at hand, attend to different problem features, or know or recall different information. Due to such discrepant views within the group, one of the first problems encountered by group researchers is appropriately representing a group, that is, research needs to begin with a model of the group that describes features of its structure and function that are important to the research question. This is often difficult because the members themselves can differ with respect to their own mental representations of the group. They can lack agreement in their beliefs about who is in the group, what its goals are, and how the group should proceed to achieve them.

There are four ways in which group researchers can deal with the problem of group representation. The first is to use the researcher’s model, with the implicit assumption that it represents not only the reality of the group, but also the members’ mental models of the group. For example, a group may be characterized as egalitarian without any assessment of members’ beliefs about status and authority within the group. Second, the researcher can elicit the perspectives of a representative of the group. Although it is often convenient to collect information from only one group member, that person may not accurately represent the entire group. A third approach to the problem of group representation is to identify and use members’ cognitive representations of the group. Typically these are represented mentally by a few discrete structures or categories. A final solution is to impart a model to group members prior to group formation and interaction. This latter option is especially popular in the laboratory study of ad hoc groups. With this approach, group members may be informed that they were selected for the group because of their knowledge in a given domain, and instructed to discuss a problem until they reach a consensus on its solution. The advantage of this last approach is that data collection begins with a common understanding within the group—and between the group and the researcher— about the group’s composition, task, and procedures.

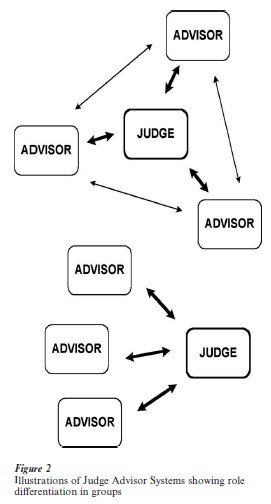

One aspect of groups in natural settings that is not captured by most laboratory research is role differentiation. What may appear to an outsider or the researcher as five persons sharing information and power to achieve their goal may be better represented as something else. Many groups are structured with a leader who is authorized to act on behalf of the group, or with a single member who emerges to take on the role of leading the group to its goal. In many circumstances, information processing becomes social when an individual seeks advice from others. The traditional group model does not adequately describe either the group with a leader or the individual seeking advice from others. A recent paradigm that accounts for role differentiation reconceptualizes the group as a Judge Advisor System. The Judge Advisor System, illustrated in Fig. 2, is a model of social decision making that was designed to distinguish between the member responsible and accountable for making a decision, known as the Judge, and the other members, called Advisors, who provide input to the Judge (Sniezek and Buckley 1995, Sniezek and van Swol 2001). The top diagram shows a group where each member can interact with any other, but the Judge is the leader who is responsible for the goal. In the bottom diagram, the Judge is also responsible for the goal, but seeks and interacts with a number of independent Advisors to elicit resources needed for goal attainment. Whenever a decision maker interacts with another person in the course of making a decision, the process becomes social, and cannot be portrayed accurately by individual decision making theory and research.

A central cognitive activity according to this view is information search. The Judge must decide to solicit advice, whom to consult, and when to stop. Research on advising in decision making has become an international scientific activity (e.g., Harvey et al. 2000). Although similar to information search from nonsocial sources, this social information search differs in that the social sources are capable of strategic and reactive behavior in the process.

4. Cognitive Conflict In Groups

At this point the reader can reasonably wonder why cognitive tasks should be done by groups and not a single individual. With so many coordination costs groups must be much more inefficient than individuals. Nevertheless, there are many reasons for using groups for cognitive tasks even when the costs of coordinating members’ difference are high. Some of these reasons are unrelated to the task itself; for example, democracy requires broad representation of views regardless of costs. In some situations, the task is simply not divisible; multiple persons are required. Yet, the primary motivation for using groups to make decisions is that the problem is important, and there is uncertainty about the quality of the various decision alternatives.

Ironically, the very same cognitive conflict in group inputs that creates challenges often provides the rationale for the use of groups. With a diversity of inputs, there is the potential for the group to follow the one that best serves members’ collective interest. Put simply, there are more ideas and strategies from which to choose. The best input in a group will, by definition, be superior to that of the average member, and superior to those of most members. For the most part, groups performing cognitive tasks have been found to produce outcomes that are better than those of the average member, though not as good as those of the best member. The extent to which the group outcome is better than that of the average individual input increases with the variation in group members’ inputs. An important point is that this result has been obtained even when analyses control for the initial bias in group members’ inputs. This assures us that the benefit of input variation cannot be attributed to groups simply discounting their poorest member.

In some cases, group outcomes can be even better than those of any group member (Sniezek and Henry 1989). Clearly the potential for such dramatic improvements in results can greatly outweigh the inefficiencies and other costs of group information processing. However, this potential benefit comes with the risk that groups can sometimes perform below the level of the poorest individual member. Therefore, a more realistic picture is that groups have the potential to be superior information processors compared to individuals working independently, but they simultaneously pose the risk of costly, inefficient, and seriously inferior performance.

Heterogeneity of inputs in a group is necessary but not sufficient for process gain. A second requirement is that those inputs be shared with other group members. One stream of research on information sharing in groups, originated by Stasser and co-workers, identifies some barriers to the sharing of information that is unique to individual group members (Stasser and Titus 1985). For starters, there is a sampling advantage for common information that means it will be more likely to be discussed in the group than unique information. Even if both common and unique information is discussed, groups tend to weight common information more than unique information. Unique information that is contributed to discussion is influential only on the judgment of the group member who contributed it. While the reduction of belief heterogeneity is necessary for group consensus, it is not always easy. This is especially true when disagreements go beyond differences in preferences to differences in preference structures. In the latter case, members have cognitive conflict, that is, differences concerning the interpretation or importance of information.

The picture that emerges from research on cognitive processes in groups shows a series of challenges unique to social information processing. Most of these problems arise from the fact that group members are not replications of an individual but varying individuals. We have seen that the persons comprising a group can vary in their beliefs about the nature of the group and its goals as well as their processing objective, focus of attention, encoding format, and memory processes. The essence of the group challenge is to reconcile member differences so that coordinated action is possible.

Bibliography:

- Fiske A P 1992 The four elementary forms of sociality: Framework for a unified theory of social relations. Psychological Review 99: 689–723

- Harvey N, Harries C, Fischer I 2000 Using advice and assessing its quality. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 81(2): 252–73

- Hinsz V B, Tindale R S, Vollrath D A 1997 The emerging conceptualization of groups as information processors. Psychological Bulletin 121(1): 43–64

- Sanna L J, Parks D C 1997 Group research trends in social and/organizational psychology: Whatever happened to intragroup research? Psychological Science 8(4): 261–67

- Sniezek J A, Buckley T 1995 Cueing and cognitive conflict in judge-advisor decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 62(2): 159–74

- Sniezek J A, Henry R 1989 Accuracy and confidence in group judgment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 43(1): 1–28

- Sniezek J A, van Swol L 2001 Trust, confidence, and expertise in Judge Advisor Systems. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes

- Stasser G, Titus W 1985 Pooling of unshared information in group decision making: Biased information sampling during discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48: 1467–78

- Wegner D 1987 Transactive memory: A contemporary analysis of the group mind. In: Mullen B, Goethals G R (eds.) Theories of Group Behavior. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 185–208