Sample Organizational Intelligence Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

For Weber (1978) and his heirs the intelligent organization was a bureaucratic organization. The files served as the repository of knowledge. Intelligence resided in the institutionalization of routines. Later it became seen as functionally specific to positions at the apex of the organization or in the technostructure. Today, it is necessary to rethink the concept in terms of virtuality and knowledge management.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Organizational Intelligence As A Historically Situated Term

Organizational intelligence—defined as the questions, insights, hypotheses, evidence that were relevant to policy—enters organizations through their strategic apex as clear, timely, reliable, adequate, and wideranging strategic information that informed embedded organizational routines. Wilensky (1967), from whom this definition is taken, regarded organizational intelligence as a variable that was directly dependent upon the degree to which there was, organizationally:

(a) Conflict or competition in relation to the external environment—typically related to the extent of involvement and dependence on government;

(b) Internal support and unity;

(c) A belief in the rationalization of internal operations and external environment; and

(d) A contingent development of size and structure, goal and member heterogeneity, and the centralization of authority (structural contingency).

Wilensky’s (1967) view was that the more organizations were developed in these terms the greater would be the need for and existence of organizational intelligence, embodied in specific types of functions, such as ‘contact men,’ ‘internal communications specialists,’ and ‘facts-and-figures men.’ His views were very much informed by the experiences of the military, defense, and intelligence agencies of the US in the Second World War and Cold War eras. In particular, he was concerned with the way that organization routines, embedded in discursive patterns, would often dictate policy long after it should have been evident that it was failing. He found examples in both the British and US strategic bomber commands of the Second World War as well as in the Vietnam War that raged at the time that he was writing. Were he writing more recently, he would, no doubt, have had some- thing similar to say about the NATO offensive against Serbia that occurred in 1999. Organizational routines and discursive patterns can often mean that even where strategic intelligence is available it may be unattended to or, if it is, not understood. Thus, organizational intelligence involves more than merely information: it involves also its application, even against discursively established routines. Organizational intelligence marks the ease with which such routines are abandoned.

2. Contemporary Views Of Organizational Intelligence

Wilensky’s (1967) view of organizational intelligence was informed largely by big, US military-industrial complex organizations. The picture changed dramatically during the 1980s, as learning from Japan became the watchword. Japanese organizations were still bureaucracies—but learning bureaucracies. What they were oriented to learning was continuous improvement of quality—and it was this that became seen as the nub of their specific organizational intelligence— learning not only to do existing things better but also to be better at innovation. The key involved unlocking total organizational intelligence rather than refining strategic intelligence. Thus, the metaphors of intelligence shifted from defense to commerce.

Using smart machines and robots for more routine work, Japanese manufacturers tried to create smarter workers for better products. Organizations sought to develop relational contracts based on similar philosophies of continuous improvement as were applied in manufacturing. Intensified global competition and the development of new digital technologies became the drivers that saw the lessons from Japan become widely distributed in existing industry, especially in the United States and Europe, by the end of the 1980s. The knowledge based information economy had arrived in which creativity, intelligence, and ideas were the core capability for sustainable success.

New information and communication technologies are crucial to such innovation processes, helping to globalize production and speed up the diffusion of technology. Information technology and globalization are transforming organizational concepts of time and space. The convergence of computing power and telecommunications reach is providing new technological and information resources in a global, digital world. As Hamel and Prahalad (1994) insisted, against Wilensky’s (1967) view of entrenched structures, size, and centralization as strategic assets, such assets become liabilities when organization competitiveness is based on radical, nonincremental innovation.

3. Intelligent Information

The development of information and communication technologies not only provides the means to process and transmit vast amounts of information but also determines the shape of organizational intelligence. If information and knowledge is to be used productively and intelligently by organizations then organizational intelligence rapidly translates into knowledge management rather than contacts, internal communications, and facts-and-figures (Wilensky 1967). Too much information is too easily available so that the key issue is not gaining information but being able to manage available knowledge.

Increasingly, knowledge and information is created and used as binary digits and transported electronically, rather than in physical forms. Ultimately, digitalization creates new structures of electronically networked organizations, replacing both individual market-based relations as well as bureaucratic structures whose resource base, in terms of size, comprises their chief strategic asset. Galbraith (1967), writing in the same year as Wilensky, although he did not foresee a digital economy, was one of the first to recognize how profound the organizational implications of the knowledge economy were in his prophetic statement of the arrival of the technocracy in The New Industrial State:

With the rise of the modern corporation … the guiding intelligence … (passes to) … a collective and imperfectly de-fined entity … (that) … embraces all who bring a specialized knowledge, talent, or experience to group decision-making. I propose to call this organization the Technostructure (1985).

The new digital technostructure allows knowledge to be developed more readily as well as to be stored, accessed, and distributed more easily, thereby simplifying organizational transactions and allowing them to be conducted remotely. Hierarchical and centralized organizations of functional specialists applying standard procedures give way to flatter, more decentralized firms with flexible arrangements by professionals who rely on real-time information, catering for specific markets or customers.

Information technology is central to each stage of this transformation, potentially enabling global coordination of enterprise networks, distributed processing, portable work, and constant access.

Enthusiasm for information technology led to a fragmentation of technologies and approaches in many organizations around local networks. Incompatibility of software, computers, and systems undermined networking capability, provoking a determined search for open systems interconnection. Integration became the driving force as organizations attempted to coordinate all operations. Constantly improving information technology promotes changing conceptions of the role of information systems. What was originally an impenetrable device of limited utility has become the main strategic resource upon which operations and strategy are founded. It is the core of contemporary organizational intelligence.

Organization intelligence involving distributed knowledge, technology, and networks focuses attention on management control. Contemporary organizations create a growing variety of linkages along the value chain by developing extensive electronic and contractual relationships with networks of suppliers, customers, and partners. The intelligence created in these systems ‘is not simply about the networking of technology but about the networking of humans through technology … not just … linking computers but … internetworking human ingenuity’ (Tapscott 1996).

How is ‘intelligence’ to be exercised in line with managerial objectives in networks? Increasingly, the rules of organization bureaucracy give way to the patterning and design of organization culture. Unlike routines produced according to formal rule, there is more scope to innovate and establish experimentation around norms. The interaction of members in a group makes it possible to exchange information on successful practices. Under these conditions groups formulate similar patterns of perception, similar interpretations of some subjects, and similar evaluation of alternatives. There is an adaptation function whereby groups arrive at successful results to satisfy their needs. By following the norms of the group, people gain acceptance from the group. Acceptance by a group signifies affiliation or cohesiveness. From the organizational viewpoint, culture aids adaptation to the environment. ‘Quality first’ is an example. If members accept such a slogan and internalize it, it can become a pattern for decision-making. This is not to suggest a culture dreamscape where resistance and conflict have been eliminated in favor of boundless creativity. Such a picture rarely corresponds with empirical evidence (DeCieri et al. 1991). Instead, it suggests a world in which obsessive self-surveillance becomes the norm—a neurosis at the core of organizational intelligence in a digital world.

Information technology is used extensively to make performance and quality standards visible and accountable to employees in organizations. For instance, large-scale video screens can express quality-related information in a simple code that all can understand, alerting people to their degree of success in meeting standards. Two aspects of this are important. First, everyone’s intelligence is enrolled to organizational effect through their becoming a constantly self-regarding subject. It is not only others who will hold one accountable—such as bosses and colleagues—but also one must hold one’s self-accountable. The fact that others are able to see, transparently, what one is accountable for, helps focus one’s energies on this enormously. One becomes a specialist in self-regarding behavior that helps to ensure that the need for external surveillance and exercise of power is minimized as the functions of control become internalized in oneself as a neurotically normal organism.

Second, this modeling of organizational intelligence in terms of individually reflexive self-control breaks down both collective strength and enhances individual isolation. The union function of articulating plural and countervailing power in the workplace becomes less relevant when, formally, unions either directly (as in Japan) or indirectly through their members are involved in the quality processes that define organizational intelligence. Where everyone is assumed to have an interest in quality to oppose it can be seen only as bloody-mindedly against the interests of employees whose jobs depend on continually improving quality—including oneself. Here is another significant discontinuity with Wilensky: organization intelligence becomes embodied in everyone, not just the ‘contact men,’ ‘internal communications specialists,’ and ‘factsand-figures men.’ In these new forms of organization, structure loses its historic role of managing power relations at a distance. For one thing, distance disappears electronically; for another, power relations flatten as teams proliferate, work becomes a series of projects, and the supervisory gaze is both internalized and becomes part of peer pressure.

Davidow and Malone (1992) identified The Virtual Corporation as a distinctive model premised on new technologies making old assumptions irrelevant. Organization design becomes virtual, enabling time and space to be collapsed and the informational controls inscribed in bureaucracy which sought to manage across them, superseded.

[T]he file cabinets of bureaucratic ritual disappear, replaced by devices that shatter the traditional physical instantiation of information and knowledge … When employees … use electronic mail or build reports from network databases, there is no original physical reality to which this information refers (Nohria and Berkely 1994).

Some find the virtual organization an attractive, if challenging, prospect, because it will have no ‘(P)reestablished boundaries, and it will be conspicuous by the absence of hierarchy. It will be completely horizontally structured and geographically distributed organization … (with) … small cluster groups that are distributed throughout the world in network-intensive, computer mediated, interactive environments’ (Estabrooks 1995).

Others are less sure that intelligent technologies necessarily make organizational intelligence. Groth (1999) presents a less sanguine, and probably more accurate, perception of the human emotional and organizational implications of information technology in which there is a continual acceleration in the rate of obsolescence of organizations’ and individuals’ knowledge base and skills—their intelligence. To counter this would require provision for the continual upgrading of skills and life-long learning: whether states or organizations will deliver this or whether it is left to markets, will be a core issue of future organizational intelligence.

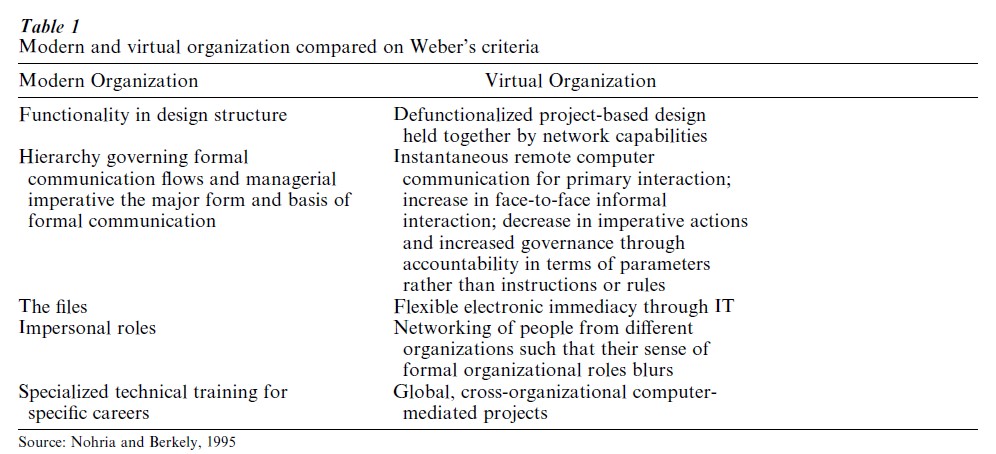

The virtual organization is almost the exact opposite of the modern organizations that Weber (1978) first identified (see Table 1 in which we contrast Weber’s modern organization with its ‘virtual’ counterpoint). Virtual organizations are invariably networked organizations. Networks may be characterized in terms of the strength or intensity of linkages, as well as the symmetricality, reciprocity, and multiplexity of their flows. The strength of a network linkage depends on the extent to which it is an ‘obligatory passage point’ in the network: can information flow elsewhere or must it route that way? The greater the amount of information, affect, or resources flowing through the passage point, then the more powerful will be those whose knowledge decodes it (Roberts and Grabowski 1996, Clegg 1989). The relations of different knowledge around these obligatory passage points embodied in different people, may be more or less symmetrical, that is, some will be more or less dependent or independent within the flow of relations. Reciprocity refers to the degree of mutual or nonreciprocal obligation that occurs in the relationship. Multiplexity refers to the degree to which those who relate to one another do so more or less exclusively. Finally, the content of the linkages is important, in terms of its degree of ‘classification’ and ’framing’: how strongly or loosely framed or bounded it is, and how tightly or loosely coded is its classification. These notions of classification and frame serve to replace the earlier emphasis that Wilensky (1967) placed on variables of organizational structure and resources as key variables in the understanding of organizational intelligence.

4. The Recursive Nature Of Organizational Intelligence

One hallmark of organizational intelligence is its fundamentally recursive character: learning transforms the existing stock of organizational know-how contained in existing normative routines and competencies. Within such a framework ‘learning is no longer … objectified in norms, procedures, routines and standards. Rather it is the cognitive activity which produces images, representations, causal links, and which is sensitive not only to human passions but to the social and organizational conditioning of thought as well’ (Gherardi 1997).

Organization learning occurs as a result of individuals learning becoming institutionally embedded in organizational ways of doing things. Where it is not, then learning will remain at the individual level. For organization learning to occur there has to be a culture that is conducive as well as management devoted to intelligence gathering, as Wilensky stressed. Many traditional tasks of management are now undertaken by computer-based technologies: managers thus must possess diagnostic, interpersonal, creative, and systems-thinking skills rather than be fact-finders. Management needs to enact interpretation, particularly where radical technological innovation creatively destroy or reduce existing competencies. Increasingly, such managers will seek to practice exploratory learning to increase organizational intelligence.

Exploratory learning is associated with complex search, basic research, innovation, variation, risk-taking, and relaxed controls. The stress is on flexibility, investments in learning, and the creation of new capabilities. Exploratory learning characterizes more intelligent organization, where radical innovation, rather than refining what already exists, produces creative discontinuities. Levinthal and March (1993) propose that the survival of any organization depends upon being sufficiently exploitative of what it already knows as to insure current viability and sufficiently exploratory as to insure its future viability. Too much exploitation risks organizational survival by creating a ‘competency trap,’ where increasingly obsolescent capabilities continue to be elaborated. Too much exploration insufficiently linked to exploitation leads to ‘too many undeveloped ideas and too little distinctive competence.’

The digital interlinking of organizations allows for learning to be distributed globally, immediately, virtually, if the intelligence acquired in one location is potentially portable to others. To do this, breakthroughs must be standardized and exploited. Standardized information is a commodity. By making tacit knowledge a commodity the dependence of exploratory insights on the individuals who produce it is eliminated. Where management can reduce individual dependency by rendering knowledge into artifacts it is possible to manipulate and combine knowledge with other factors of production in ways that are impossible if it remains a human possession. Abstract properties need to be developed for the phenomena to become a standardized commodity—so that it becomes alienable, like a property title—entailing a shift from knowledge-workers to knowledge as a pure factor of production, usually embodied in systems and software.

It is easy to transmit exploratory learning embedded in innovation throughout the world when it is embedded in a systems and software. But these may not capture the embedded tacit knowledge involved in making exploratory innovation work. A solution is at hand: work processes can be videotaped, scanned on to computer, and downloaded instantly by the globally networked organization, thus disseminating it globally, instantly, to individual desktops and workstations. Thus, we are all potential ‘contact-men’ now and anyone connected to the World Wide Web, intranet, or Internet, can be an ‘internal communications specialist’ and ‘fact-finder.’ Organizational intelligence no longer belongs to a specific organizational entity or to its apex: it can be virtually everywhere.

Bibliography:

- Clegg S R 1989 Frameworks of Power. Sage, London

- Davidow W H, Malone M A 1992 The Virtual Corporation: Structuring and Revitalising the Corporation for the 21st Century. Harper Collins, New York

- DeCieri H, Samson D, Sohal A 1991 Implementation of TQM in an Australian manufacturing company. International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management 8(5): 55–65

- Estabrooks M 1995 Electronic Technology, Corporate Strategy and World Transformation. Quorum, Westport, VI

- Gherardi S 1997 Organizational learning. In: Sorge A, Warner M (eds.) Pocket International Encyclopedia of Business and Management: The Handbook of Organizational Behaviour. International Thomson Business Press, London pp. 542–51

- Groth L 1999 Future Organizational Design. The Scope for the IT-based Enterprise, Wiley, Chichester

- Hamel G, Prahalad C K 1994 Competing for the Future. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

- Levinthal D A, March J G 1993 The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal 14: 95–112

- Nohria N, Berkely J D 1994 The virtual organization: Bureaucracy, technology, and the implosion of control. In: Heckscher C, Donnellon A (eds.) The Post-bureaucratic Organization: New Perspectives on Organizational Change. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 108–28

- Roberts K H, Grabowski M 1996 Organizations, technology and structuring. In: Clegg S R, Hardy C, Nord W (eds.) Handbook of Organization Studies. Sage, London, pp. 409–23

- Tapscott D 1996 The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence. McGraw Hill, New York

- Weber M 1978 Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Wilensky H L 1967 Organizational Intelligence: Knowledge and Policy in Government and Industry. Basic Books, New York