Sample History Of Genocide Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Genocide is any intentional act to physically eliminate a non-combatant group in whole or in part by direct assault, or by inflicting deadly life conditions including measures to prevent biological, economic and cultural reproduction.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

This research paper will outline the development of genocide research as well as the tasks of this young academic discipline (Sect. 1). It will, in Sect. 2, deal with the problem of applying the twentieth-century term genocide to a wide variety of mega-killings which have happened throughout history. The term genocide has generated a tendency not only to rewrite, but also to morally judge anew, historical events to settle recent political accounts. Groups whose ancestors have suffered massacres at a period in which neither they themselves nor their victorious opponents had drawn up or adhered to international legal standards outlawing such atrocities may yet label their past fate as genocide to attract attention to contemporary plights. The paper will try to circumvent this extra-scholarly or ideological use of the term genocide by implicitly or explicitly using a caveat of the sort that an event called genocide ‘today’ was not seen as such then. It has to be stressed that all figures used in this research paper are estimates. There is no such thing as an undisputed figure for even the best researched genocides.

1. The Term Genocide And The Development Of Genocide Research

Genocide is not only a historical concept but also an international crime defined by the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In its Article II

genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) killing members of the group; (b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

The crimes mentioned in paragraphs (a) to (e) of Article II of the Convention are generalizations of practices employed by Nazi Germany after September 1, 1939 (beginning of World War II) against Slavs and/or Jews, and gypsies. The UN Convention was mostly written by a Polish lawyer and Holocaust refugee, Raphael Lemkin (1900–59), who had first in 1933 proposed a similar measure to the ‘League of Nations.’ In 1943, he had termed the crime in Polish as ludobojstwo (lud=people; zabojstwo=murder). A year later, he translated it into English as genocide (from Greek genos=people, and Latin caedere=kill, see Lemkin 1944, p. 79).

Since the UN Convention—today signed by some 140 nations—excluded ‘politicide’—the murder of any person or people because of their politics or for political purposes—as well as ‘ideological genocide’—the murder of any person or people because of their ideology, theory or knowledge—scholars have broadened the concept. Rudy Rummel’s term ‘democide’ may be considered as the most comprehensive one. It is the murder of any person or people including genocide in the international legal sense, politicide as well as ideological mass murder (Rummel 1996, p. 39).

Besides the narrower term genocide and the more inclusive term democide the term ‘crimes against humanity’ is still in wide use. It was coined on May 24, 1915 by France, Great Britain, Russia, and the USA on behalf of the slaughtered Ottoman Armenians as ‘new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization.’ The term ‘crimes against mankind’ created, on October 12, 1942, in London (Declaration of St. James) to denounce the Nazi Holocaust of European Jewry is also still in use. Less known though quite appropriate is Gracchus Babeuf’s French term ‘populicide,’ a shorthand for his ‘systeme de depopulation’ executed—during the French Revolution—in the Vendee (1793/94) by killing its entire royalist peasantry of some 120,000 (Babeuf 1795).

The discipline of comparative genocide research draws on the entire corpus of historical research of the last three millennia. Mega-killings have always attracted the attention of laymen and scholars alike. Yet, a first world history approach to genocide was tried by Lemkin who had drafted three volumes on the History of Genocide by 1959 (Jacobs 1999). Several publishing houses had turned him down. The manuscripts are only now being prepared for publication by Steven L. Jacobs.

The 1967–1970 massacres of half a million Ibos in Biafra/Nigeria triggered a new interest in the subject. In 1970, Yvan van Garsse published A Bibliography: of Genocide Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes (Garse 1970). The genocide, in 1971, of some 1.5 million citizens of East-Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) also has drawn a steady albeit not widespread attention to the subject. Both killings had world wide television coverage. Only a year later, in 1972, The Twentieth Century Book of the Dead by Gil Elliot became the first major published monograph devoted to comparative genocide research (Eliot 1972) . In 1975, sociology entered the field with Dadrian (1975). Irving Louis Horowitz’s Genocide: State Power and Mass Murder followed in 1976 (Horowitz 1997). In 1981, Leo Kuper reached a major academic publisher, Yale University Press, with Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century (Kuper 1982). More systematically and historically minded works followed in 1990 with Fein’s (1990) Genocide: A Sociological Perspecti e as well as Chalk’s and Jonassohn (1990) The History and Sociology of Genocide.

The first—one person—institute devoted to the subject: ‘Institute on the Holocaust and Genocide,’ was founded in 1979 by Israel W. Charny in Jerusalem. Helen Fein followed in 1982 with the ‘Institute for the Study of Genocide,’ in New York. Next were Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn with the Canadian ‘Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies’ (Montreal, Concordia University). Australia with the ‘Centre for Comparative Genocide Studies’ (Macquarie University), and Europe with the ‘RaphaelLemkin-Institut fur Xenophobieund Genozidforschung’ (University of Bremen, Germany) followed in 1993. An international ‘Association of Genocide Scholars’ was established in 1995 with some 150 members by mid-2000. The first encyclopedia of genocide was published in Germany (Heinsohn 1999). A similar endeavor in English followed shortly afterwards (Charny 1999). Both works, with a combined volume of some 1,200 pages, cover most of the contents of this research paper.

Historical, sociological, and sociopsychological studies of genocide aim at the assessment of genocidal potential as well as the formulation of means to prevent the crime. Interventions against ongoing genocides are rather dealt with in studies of warfare than in comparative genocide research. The prevention of genocide requires an early warning system. Historically, roughly 25 percent of high risk nations have transformed their perpetrator potential into actual genocide (the rate is higher for democide). Since every genocide needs certain steps of preparation which are difficult to conceal, like, e.g., registering the victims and training the killers, all nations with perpetrator potential (today close to 100) may one day be scanned for these red alert signals indicating the imminence of a genocide.

2. History Of Genocide

Because of its modern provenance it is difficult to employ the term genocide to the common periodization of history. Homer’s Iliad (VI: 55–62), e.g., paints, as perfectly legitimate, an intention that today would be considered as genocidal in its full legal sense:

‘‘My good Menelaos’’ [king of Sparta], said he [Agamemnon, king of Mycene], ‘‘this is no time for giving quarter. Has, then, your house fared so well at the hands of the Trojans? Let us not spare a single one of them—not even the child unborn in its mother’s womb; let not a man of them be left alive, but let all in Ilius [Troy] perish, unheeded and forgotten.’’ Thus he did speak and his brother was persuaded by him, for his words were just.

Moreover, a practice of killing considered the expectable as well as acceptable outcome of conflict in an early period of history may continue to this very day. As an example in question one may look at the Yanomami Indians of Southern Venezuela and Northern Brazil. They must—since 1980—be considered a possible victim of genocide by modern settlers and—at the very same time—were successful in nearly wiping out a neighboring tribe (Keegan 1993, p. 97).

2.1 Tribal Societies

Genocidal acts in the modern sense were hardly distinguishable from acts of war in tribal societies— covering the longest stretch of human history— because there was no separation of noncombatant civilians and warriors. Warfare was ‘‘‘ecological’’ in motivation’ and led to the redistribution of hunting and fishing grounds or arable land ‘from the weak to the strong’ (Keegan 1993, p.101). Means of these wars were ‘battles of annihilation’ or, if space allowed, ‘displacement of the weaker’ (Keegan 1993, pp. 29, 387). Genocidal tribal raids continued well into the second half of the twentieth century in territories of the Amazon, New Guinea, the Philippines and else- where: ‘Typically the goal in such raids is to destroy an entire village or settlement, the common intention being to kill everyone, perhaps excepting a few of the younger women and children who are carried off for incorporation into the home group’ (Glick 1994, p. 45).

2.2 Early Antiquity

Early stages of civilization (Early and Middle Bronze Age with priest-kingship feudalism) saw tribal practices of annihilation on a larger scale: ‘I slew them without sparing them, they sprawled before my horses, and lay slain in heaps in their blood,’ Egypt’s Pharaoh Ramses II (conventionally dated 1279 to 1212) boasted after a campaign against the Hittites whose leader, then, begged him for mercy: ‘Look, you spent yesterday killing a hundred thousand and today you came back and left no heirs. Be not hard in your dealings victorious king’ (Lichtheim 1976, pp. 70 f.). Other powers of the Ancient Near and Far East behaved very much in the same way, as did Bronze Age, i.e., Mycenaean Greece.

2.3 Antiquity City States

The annihilation practices of time immemorial were cast into a principle by Athenians. When, in the Peloponnesian War (431 to 404 BC), Athens had decided to wipe out Sparta’s ally Melos, the admirals in charge tried to formulate an eternal law underlying their action:

Our knowledge of men leads us to conclude that it is a general and necessary law of nature to rule wherever one can. This is not a law that we made ourselves, nor were we the first to act upon it when it was made. We found it already in existence, and we shall leave it to exist for ever among those who come after us. […] We know that you or anybody else with the same power as ours would be acting in precisely the same way. […] The Melians [in 415 BC] surrendered unconditionally to the Athenians, who put to death all the men of military age whom they took, and sold the women and children as slaves (Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, (1954 trans) V: 85 ff.).

As a first step away from mutually slaughtering their males, the Greeks developed the practice of exchanging prisoners of war.

Within the Roman Empire—a private ownership based society on a much larger scale—the practice of destroying enemies who had caused problems in the past was continued. The elimination of Corinth (metropolis of mainland Greeks) and Carthage (metropolis of Phoenicians) in 146 BC, of Numantia (capital of Spanish Celtiberians) in 134 BC, and the elimination of the Etruscans (92 BC) and the Samnites (82 BC) as major opponents in Italy proper provide typical examples with 50,000 to 150,000 dead in each case. Of course, the opponents acted in the same manner as, e.g., in the slaughter of the inhabitants of the Greek cities Selinus and Himera (Sicily) in 409 BC by the Phoenicians of Carthage. In 88 BC all Romans and Italians, including women and children, living in Greek Asia Minor were put to the sword by orders of Mithradates VI. The Romans of Britannia met a similar fate in 61 BC. Within the Roman Empire a ius gentium was developed for strangers who did not hold citizenship with, sometimes, more protection for these minorities than for full citizens.

Parallel to practices of the Greek City States and the Roman Empire, movements against blood sacrifice emerged around 600 BC. Well known are Buddhism in India and the Pythagoreans of Classical Greece. It was, however, monotheistic Judaism whose moral code—albeit slowly—came to influence international ethics most deeply. To overcome expectations of salvation tied to the slaughter rituals of blood sacrifice, Hebrew prophets found a new moral vision: ‘I desired mercy, not sacrifice; and the knowledge of God more than burnt offerings’ (Hosea 6:6). The sanctity of life became the highest principle: ‘Thou shalt not kill’ (Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17)] including—in its universal character—the strict outlawing of infanticide.

The Torah—rather a moral compilation than a historical record—emphasizes the sanctity of life as the core of the law and as a value identical with goodness (‘the good law’): ‘See, I have set before thee this day life and good. […] I call heaven and earth to record this day against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live’ (Deuteronomy 30:15, 19). From the principle of life’s sacredness derived other commandments like ‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself’ (Leviticus 19:18). Anti-xenophobic teaching followed suit: ‘And if a stranger sojourn with thee in your land, you shall not vex him. But the stranger that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one born among you, and thou shalt love him as thyself’ (Le iticus 19:33–34). ‘Are ye not as children of the Ethiopians unto me, O children of Israel? Saith the Lord. Have not I brought up Israel out of the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor, and the Syrians from Kir’ (Amos 9:7).

Against Judaism, the first recorded order (of Haman) for an ideological, though abortive, genocide (also called religiocide) was issued in the Akhaemenid Empire of fourth century BC: ‘And the letters were sent by posts into all the king’s provinces, to destroy, to kill, and to cause to perish all Jews, both young and old, little children and women, in one day’ (Esther 3:8 13). Christians who had adopted the Jewish rejection of blood sacrifice to planetary deities actually suffered the first well recorded religiocides. The edict of Emperor Decius of AD 250 forced them to eat sacrificial meat or suffer death. Four more edicts by Diocletian from AD 303 304 repeated the order upon pain of death. The massacres ended in AD 312 when Constantine the Great converted to the new faith.

2.4 Middle Ages

The Middle Ages saw attempts at a Pax Romana, directed by the Papal See. Its concept of a Pax Dei (peace of God)—developed since AD 975 and extended over all Christian lands at the Synod of Clermont (AD 1095)—outlawed war from Wednesday night to Monday morning as well as on Christian holidays. Excommunications and interdicts were the only means of enforcement. It was the beginning of international law based on the Judeo-Christian code of ethics. Yet, the transgressions were severe and, in modern terminology, definitely genocidal.

The crusades—starting in AD 1096—not only brought massacres of thousands of Jews in Germany and tens of thousands of Jews and Muslims in Jerusalem (AD 1099), but also of fellow Christians. Against Pope Innocent III’s interdict, Dalmatia’s port Zadar, arch rival of Venice, was bathed in the blood of all its inhabitants in November 1202 during the fourth Crusade by French and Italian troops transported on Venetian ships. The same men butchered 2,000 inhabitants of Greek Constantinople on April 13, 1205 before they went on a three-day-rampage of indiscriminate slaughter, not sparing women and children.

Since 1167, the Cathars (from Greek katharoi pure), called Albigensians after the French city of Albi, suffered a series of religiocides by Catholic forces, because they rejected any spilling of blood and did not believe in the resurrection of Christ, and the Holy Communion as the residue of blood sacrifice within Christianity. By 1234 the Cathars were wiped out with the massacre of Beziers as the largest slaughter of this crusade in which all 15,000 inhabitants were killed.

A few years later, in AD 1211, Gengis Khan’s Mongols (Morgan 1986)—with no authority to arouse their consciousness by threats of excommunication or invoking the image of all men as protected children of the one God—began their terrifying campaigns from the Japanese to the Baltic Sea. To turn their fertile areas into horse pastures the Mongols have, up to AD 1290, eliminated some 25 million Chinese. Another 5 million perished in Persian, Arab, and Christian territories where the Steppe warriors revived the memory of Attila’s fifth century Huns. Behind their lines, the Mongols used to kill everyone perceived as a future threat, i.e., all males not suitable to join their ranks. Defeated armies were allowed a brief lease to life by serving as shields or trail blazers for advancing Mongol troops. Tamerlane, a pious Muslim, supposedly had, in a single day of 1398, some 100,000 Hindus strangled in sight of the walls of Delhi which had rejected surrender. In 1402, he dealt a mortal blow to Arab civilization by killing 90,000 inhabitants of Baghdad.

2.5 Modern Period

A sovereign’s right to war (ius ad bellum) dominated the period of sixteenth to nineteenth century in which Europe came to dominate the world. What happened within a war was more or less up to the sovereign. Laws of warfare or the definition of crimes of war (ius in bello) had to wait for the turn of the nine-tenth/twentieth century. In Europe as well as overseas, the results were genocidal. To give only two examples, Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital in the valley of Mexico with its 100,000 inhabitants, was totally annihilated by Cortes’ Spaniards in 1521. All 30,000 inhabitants of German Magdeburg, the richest city of Protestantism, were slaughtered on May 10, 1631 by Catholic troops under General Tilly in the Thirty Years’ War.

The European Population Explosion—beginning at the end of the fifteenth century, and still not fully understood—bestowed this small continent with 25 percent of world population by 1900. During the same period, some 60 million young Europeans, with the superior military technology of their ownership-based economies but no attractive positions in an overcrowded continent, conquered their settlement space in the Americas, Australia, Africa, and Northern Asia. In the wake of this ‘emigration,’ a population of 55 to 85 million native Americans estimated for 1492 (Spanish conquest) was reduced by 85 to 95 percent around 1650. Between 250,000 and 500,000 native Australians estimated for 1788 (British conquest) were reduced to 60,000 by 1921. All means of killing were employed from outright genocide to infections— including intentional ones. Africa, between 1500 and 1870, lost up to 20 million inhabitants into American slavery with 2 million dying on transport. The slave trade within Africa may have cost, for the same period, the lives of 4 million. On the slave routes to—mostly Islamic—Asia another 11 million may have perished in these gigantic democides (Rummel 1996, p. 48).

Though not an invention of modern times, politicide became one of the most heinous activities of this period. It does not necessarily include the killing of the families of the victims. However, in a so-called ‘Vespers’ in which politicide is turned against a foreign elite, it usually grows into a full blown genocide. It took its name from the Easter massacre in Palermo on March 29, 1282, at the hour of evening prayer (Vespers) when the French in control of the Kingdom of Sicily were killed with their families (‘Sicilia Vespers’). It had been preceded, in 1268, by the butchering of some 5000 members of the Hohenstaufen elite of Sicily by the hands of the French conquerers. The best remembered example of politicide was the annihilation, after eight inconclusive civil wars, of the Protestant leadership of France (ca. 100,000 victims), starting on Saint Bartholomew’s Day (August 24, 1572) when the Huguenots—easily recognizable by their black clothing—were guests at the royal marriage of Henri of Navarra and Marguerite of Valois. The politicide, in February 1579, against Novgorod, Russia’s richest city, by Ivan IV (the Terrible) was peculiar insofar as the Tsar had put together special killing units—the ‘Oprichniki’—because the army was not trusted to act ruthlessly enough. In the ‘Ulster, Massacre’ (October 23, 1641), as the last ‘Vespers’ of Western Europe, Irish rebels killed most of the Protestant British settlers and administrators on their island. The Creoles of Haiti delivered their French masters a ‘Vespers’ in 1791 1805 as did, in 1857 58, albeit with no lasting success, the sepoys to the British masters of India.

2.6 Twentieth Century

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 with The Regulations Respecting the Law and Customs of War on Land prohibited, in Articles 22–8, the murder, illtreatment, or deportation of enemy civilians and prisoners of war. The use of poison and special ammunitions was banned. However, a nation’s harm to its own civilians was not taken into consideration. This had to wait for the ‘Istanbul Trials,’ installed in January 1919 to inflict punishment on those responsible for the Armenian massacres. On April 10, 1919, Mehmet Kemal Bey, procurator of the province Bogazliyan, became the first person executed for genocide, then called crime against humanity. In the Nuremberg Trials of Nazi-Germany’s leadership (1945 46) as well as in the Tokyo Trials of Imperial Japan’s leaders (1946–48), ‘International Military Tribunals’ further developed the legal tools to punish perpetrators of crimes against humanity. Special United Nations courts explicitly devoted to the crime of genocide started, in 1993, to prosecute the perpetrators in Yugoslavia (‘ethnic cleansings,’ since 1991) and, a year later, in Rwanda (genocide of Tutsis in spring 1994). The statute for a permanent ‘International Criminal Court’ was passed in Rome on July 17, 1998.

The entire twentieth century is on record for close to 180 million victims of democide according to Rummel’s statistics. The extermination of the Ottoman Armenians (1894–96, 1909, 1915/16, 1919, 1923) combined strategic, racial, and ideological intentions (Dadrian 1995). A shrinking empire was to be consolidated by a homogenous pan-Turkic population within an undivided settlement space under Islam as the only religion. That’s why not only more than 1 million Armenians suffered genocide but also other Christian minorities like Maronites (1860), AssyroChaldaeans (1915), and Greeks (1915–23) with a combined death toll of some 440,000.

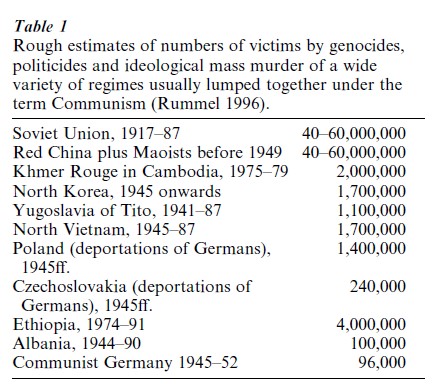

Since 1917, single party totalitarian regimes with agendas may have killed up to 110 million people (Rummel 1996, Courtois 1997). After World War II, ‘one-party communist states are 4.5 times more likely to have used genocide than are authoritarian states’ (Fein 1933b, p. 79)

The figures given in Table 1 are all estimates. Totalitarian regimes are not only known for most of the killings of the twentieth century, but also present the most difficult problems for research because archives were destroyed and many deeds never re- corded. Thus, totalitarian regimes have to live with possibly exaggerated figures of their atrocities.

Extreme anti-capitalism slowed economic development though superior prosperity was promised. The shortcomings were frequently blamed on sabotage and/or party comrades still infested with the reactionary spirit of ownership. This view was used to justify massive party purges like the ‘Great Terror’ in the Soviet Union (1934, 1936–38) with more than 7 million or the ‘Cultural Revolution’ in China (1964–75) with nearly 8 million dead.

Annihilation through forced labor in camps was initiated by Trotzki on June 26, 1918. By 1922, 23 Soviet camps were at work, forming the nucleus of Stalin’s Gulag fully emerging in 1928, and eventually running some 8000 camps. Working people to death became, in the long run, the most devastating killing tool of history. It allowed the elimination of opponents by simultaneously using them for the creation of big projects—like canals, railroads, subways, etc.—to prove by ‘miracles’ the promised productive superiority of communism that otherwise was wanting.

The traditional siege tool of man-made famines had to wait for the twentieth century to be welded into the most efficient fast-killing techniques ever. To crush national ambitions of the Ukraine, for example, a famine was turned into the mass death of some 7 million in the single winter (4 months) of 1932 33. Ethiopia’s Derg managed to kill up to 4 million peasants between 1982 and 1986 by the same means, often intentionally aggravating natural disasters.

The mega-killings by left totalitarian regimes came as a combination of politicides (elimination of like minded rivals for power), genocides (elimination of minority nations, mostly in the Soviet Union and the Peoples Republic of China), and ideological genocides (foremost the elimination of proprietors or property- infested citizens). The latter category probably became the largest victim group in history with some 50 million dead (55 percent in China, 40 percent in the Soviet Union, 5 percent in the other communist regimes).

Of all twentieth-century totalitarian regimes, Nazi Germany was the most genodical. Following September 1, 1939, deformed newborn and mentally handicapped Germans—as well as some German soldiers severely wounded in the military campaign against Poland—were killed by injections or in gas chambers. Close to 130,000 handicapped eventually ended in this so-called euthanasia operation. Later exterminations struck Gypsies, stigmatized as socially inferior, as well as non-reproductive homosexuals etc. A bigger target, however (outlined in the ‘Generalplan Ost’ (Masterplan East)) were 100 million Slavs (Czechs, Poles, White-Russians, Ukrainians, and Russians) living between Germany’s Eastern border and the Ural Mountains, a territory marked to become Germany’s ‘Lebensraum.’ Of the Polish elite, 75,000 members, most of them holders of academic degrees, were killed in autumn 1939. The second Eastern campaign, against the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941), was aimed at the immediate killing of 30 million Slavs. Another 30 million were destined to be worked to death to lay the infrastructure for German settlements. The remaining 40 million were to be driven into Siberia with a calculated death toll of another 10 million. With 13 million Slavic civilians and prisoners of war killed by 1945 (Kumanev 1990, Vitvitsky 1990), Nazi Germany had fallen short of its 70 million goal but still had committed the largest twentieth-century genocide explicitly directed against a particular ethnic group. Nazi Germany’s Eastern campaigns, thus, were not only massive wars but also militarily enforced genocides (Hillgruber 1993).

In connection with the Eastern wars, 5 to 6 million Jews were killed. Though a ‘theory of the Holocaust is lacking’ (Herbert 1998, p. 66), Hitler’s practice of ‘strengthening’ Germany by killing its handicapped and of gaining settlement space through genocide of its Slavic inhabitants put him inevitably against the Torah. To him the sanctity of life was a Jewish ‘invention,’ a weakening ideology that could be cleansed from the German sphere of influence by exterminating its ‘carriers.’ The Holocaust, in this perspective, was a ‘genocide for the purpose of reinstalling the right to genocide’ (Heinstohn 2000, p. 424).

Since 1944/45, some 100 acts, fulfilling the definition of the UN Genocide Convention have taken place. In the two decades from 1980 to 2000, some 80 distinct ethnic and religious groups—mostly in Africa, Asia, and Latin America—were victimized with 12 of them going through full blown genocide: Bosnian Muslims, Kurds, Tibetans, Dinka (Sudan), Nuba (Sudan), Shilluk (Sudan), Isaaq (Somalia), Tutsi (Rwanda), Mayans (Guatemala), Albanians (Serbian Kossovo), and Timorese of Indonesia (Harff and Gur 1996, updated by the author).

2.7 The Future

Ecologically and ideologically motivated genocides most probably will have a future in the twenty-first century. Politicides may also occur wherever solidly established democratic structures are missing. Democracies usually do not go to war against each other. The same cannot be said for democide like nuclear and carpet bombing against totalitarian powers with, e.g., a death toll of 1.5 million in Germany (600,000) and Japan (900,000) during World War II.

The prevention of genocide by spreading democracy remains the preeminent goal for the future. Meanwhile, some experience with intervention has been made, in 1999, in Kossovo and Timor. To preempt the cruelties unavoidable in an intervention by force, genocide early-warning stations are now seriously considered. They may be in place within a few years.

Bibliography:

- Babeuf F N 1795 Du systeme de la depopulation … avec la guerre de la Vendee. Franklin, Paris

- Chalk F, Jonassohn K 1990 The History and Sociology of Genocide. Analysis and Case Studies. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Charny I W (ed.) 1999 Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, CA

- Courtois S (ed.) 1997 Le Li re Noir du Communisme: Crimes, terreur, repression. Laffont, Paris

- Dadrian V N 1975 A typology of genocide. International Review of Modern Sociology 5: 201–12

- Dadrian V N 1995 The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus (1995), Berghahn. Providence, RI

- Elliot G 1972 Twentieth Century Book of the Dead. Allan Lane The Penguin Press, London

- Fein H 1993a Genocide: A Sociological Perspective. Sage Publications, London

- Fein H 1993b Accounting for genocide after 1945: Theories and some findings. International Journal on Group Rights 1: 79–106

- Garsse Y v 1970 A Bibliography: of Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes. Studiecentrum voor Kriminilogie en Gerechtelijke Geneeskunde, Sint Niklaas Waas, Belgium

- Glick L B 1994 Religion and genocide. In: Charny I W (ed.) The Widening Circle of Genocide. Genocide: A Critical Bibliographic Review. Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ, Vol. 3, pp. 43–74

- Harff B, Gurr T 1996 Victims of the state: Genocides, politicides and group repression from 1945 to 1995. In: Jongman A J (ed.) Contemporary Genocides: Causes, Cases, Consequences. PIOOM. Leiden, The Netherlands, pp. 33–58

- Heinsohn G 1999 Lexikon der Volkermorde, 1st edn. 1998, Rowohlt, Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Homburg, Germany

- Heinsohn G 2000 What makes the Holocaust a uniquely unique genocide. Journal of Genocide Research 2: 411–30

- Herbert U (ed.) 1998 Nationalsozialistische Vernichtungspolitik 1939–1945: Neue Forschungen und Kontro ersen, Fischer, Frankfurt, Germany

- Hillgruber A 1993 Hitlers Strategie: Politik und Kriegfuehrung 1940–1941 [1963]. Bernard & Graefe, Bonn, Germany

- Horowitz I L 1997 Taking Lives: Genocide and State Power. Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ

- Jacobs S L 1999 The Papers of Raphael Lemkin: A First Look. Journal of Genocide Research 1: 105–14

- Jonassohn K, Bjornson K S 1998 Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations in Comparative Perspective. Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ

- Keegan J 1993 A History of Warfare. Knopf, New York

- Kumanev G A 1990 The German occupation regime in occupied territory in the USSR (1941–1944). In: Berenbaum M (ed.) A Mosaic of Victims: Non-Jews Persecuted and Murdered by the Nazis. New York University Press, New York, pp. 128–41

- Kuper L 1982 Genocide: Its Political Use in the Twentieth Century. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Lemkin R 1944 Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, DC

- Lichtheim M 1976 Ancient Egyptian Literature. Volume II: The New Kingdom. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Morgan D 1986 The Mongols. Blackwell, Oxford

- Rummel R J 1995 Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. Center for National Security Law, Charlottesville, VA

- Rummel R J 1996 Death by Government 1994. Transaction, New Brunswick, NJ

- Thucydides 1954 The History of the Peleoponnesian War, trans. R Warner. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, UK

- Vitvitsky B 1990 Slavs and Jews: Consistent and inconsistent perspectives on the holocaust. In: Berenbaum M (ed.) A Mosaic of Victims: Non-Jews Persecuted and Murdered by the Nazis. New York University Press, New York, pp. 101–8