View sample Youth Movements Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Youth movements are the organized, conscious attempts by young people to bring about or resist societal change. The formal organization and coordinated activities of youth movements distinguish them from brief episodes of youthful unrest and collective behavior. Rooted in generational tensions and specific sociohistoric conditions, the defining characteristic of youth movements is that they are staffed and carried out largely by young people—typically between the ages of 17–30—who join together to protest adult authority and take it upon themselves to transform society. Ranging from a small number of members to hundreds of thousands of active supporters, youth movements have included student movements, cultural (literary, artistic, musical, ethnic, religious, countercultural) movements, peace and antiwar movements, nationalist and political movements, and environmental–ecology movements. Young people spontaneously may initiate their own movements for change, or youth movements may be sponsored by adults to supplement the activities of larger social and political movements.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. The Problem Of Youth And Youth Movements

Throughout history, adults have defined young people as ‘a problem.’ Wedged between childhood and adulthood, it has long been recognized that young people’s idealism, energy, impetuousness, and desire for independence draw them to action and put them at odds with adults. Although incidents of youthful unrest and collective behavior have been recorded since antiquity, full-fledged, organized youth movements did not emerge until the early nineteenth century in Europe. The impetus for youth movement activity stemmed from the forces of modernization and from the Enlightenment, which ushered in the new values of freedom, equality, and self-determination. Increasing in number and geographic location from the early nineteenth through the twentieth centuries, youth movements occurred on a global scale during the 1960s and 1980s. Youth movements have toppled governments and have been a force for democracy and societal reform as well as violence, terrorism, and bloody revolution.

The study of youth movements ranges from personal and journalistic accounts to detailed descriptions, analyses, and research investigations by historians, sociologists, political scientists, anthropologists, psychologists and psychiatrists throughout the world. As a result, information about youth movements, while plentiful, is fragmented and scattered among many disciplines and countries.

Several theoretical perspectives have influenced the way youth movements are perceived and studied. Advocates of a life-course approach—based largely on Freudian psychodynamic theory—attribute youth movements to generational rebellion, young people’s life-cycle characteristics and needs, and deep-seated emotional conflicts between youth and adults (Erikson 1968; Feuer 1969). From a cohort-generational perspective, youth movements are viewed as products of a rapidly changing social order and unique growing-up experiences that exacerbate age-group tensions and relations, and, at times, may heighten young people’s generational consciousness and organized behavior. In addition, because of their varying social locations in society, young people may disagree over the direction that change should take and form generation units or competing groups within the larger generational movement (Mannheim 1952; Ortega 1962).

According to socialization theory, young people involved in youth movements are not rebelling against their parents but are carrying out values learned in the home. Schools, universities, peer groups, and the media also act as influential sources of socialization that promote or reinforce youthful activity (Flacks 1971; Keniston 1971). Historical conditions are the focus in another perspective on youth movements. According to this view, the formation, structure, and demise of youth movements are affected strongly by specific local, national, and international trends and events. In general, societal dislocations, inequities, and widespread discontent in conjunction with new opportunity structures and resources explain why youth movements occur during certain periods and not others (Esler 1971; Tilly 1975).

2. Historical Generational Patterns Of Youth Movement Activity

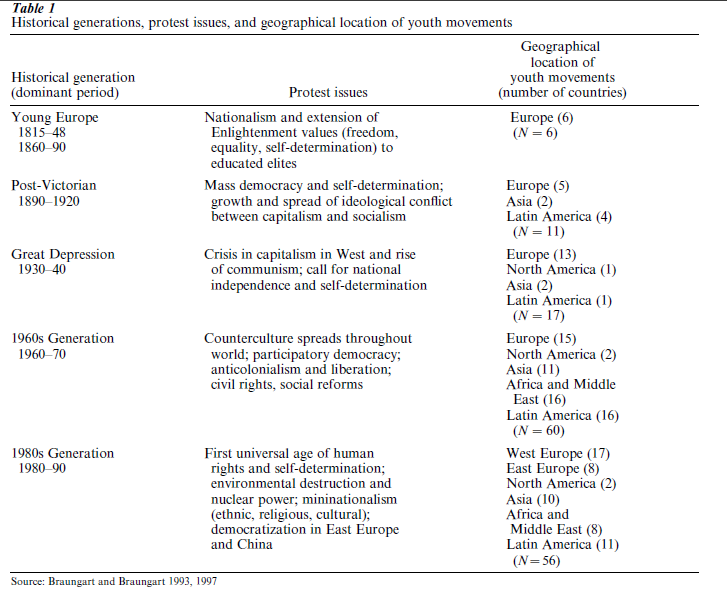

A survey of modern history indicates that youth movements erupt periodically and became global in scope by the 1960s. Moreover, youth movements tend to cluster during particular eras, followed by periods of relatively little youth unrest. A cluster of youth movements represents a historical generation. Over the last nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there have been five identifiable historical generations or waves of youth movement activity: Young Europe, PostVictorian, Great Depression, 1960s Generation, and 1980s Generation. Historically, most youth movements have formed over issues of citizenship, including freedom, equality, self-determination, nationalism, and cultural expressiveness (Braungart and Braungart 1989b, 1993). To provide an overview of the growth of youth movements during this period, the five historical generations are described briefly in Table 1.

Young Europe was the first wave of youth movement activity where young people fought for Enlightenment values. Napoleon’s defeat in 1815 ushered in an age of nationalism, romanticism, and liberalism that inspired university students to organize movements for national independence. First, in Germany and then elsewhere in Europe, students called for an end to absolutism and the ancien regime in favor of the modern nation-state. The Post-Victorian Generation reflected another period of upheaval in modern history. A new era of mass democracy and self-determination encouraged young people to organize against colonialism and imperialism. Fin de siele youth mobilized to challenge the last of the great empires (Victorian, Austro– Hungarian, Ottoman, Ch’ing, Meiji, Romanov), and young socialists fought nineteenth-century liberals. The Great Depression Generation reacted against the economic failures of capitalism and waged intense ideological struggles involving totalitarian regimes (communist, fascist), authoritarian states, and liberal democracies. The call for national independence reached developing countries by the 1930s.

The 1960s Generation, rooted in the post-World War II baby boom, faced several international challenges, including the East–West Cold War and the growing economic gap between rich and poor countries. In unprecedented numbers, young people demanded freedom, equality, and peace, while countercultural lifestyles and behavior spread rapidly around the world. The ‘revolution of rising expectations’ generated youth movement activity in developing countries. The 1980s Generation mobilized over issues relating to human rights, freedom, and democracy. The Cold War was under attack by young people in Western and Eastern Europe; youth in Asian countries demanded greater democracy; the North–South economic gap worsened and spawned youthful protests in developing countries; and ethnic and religious confrontations involving young people erupted in all global regions. What started in Berkeley in 1964 had reached Beijing by 1989.

3. Intergenerational And Intragenerational Dynamics Of Youth Movements

An examination of several hundred youth movements in history indicates a number of common patterns in generational activity. Specifically, much of the momentum for youth movements is derived from the intergenerational conflict between young people and adult authorities and the intragenerational conflict among competing generation units or youth groups. When the research is pulled together to provide an understanding of youth movement activity, the principal dynamics of generational conflict are identified and suggest a synthesis of the various theoretical perspectives.

Intergenerational conflict is the central dynamic of youth movement activity and plays a significant role in mobilizing young people to transform society. The generational tensions, misunderstanding, and conflict between youth and adults stem from two sources: (a) the life-course differences, needs, and orientations of young people that set them apart from adult needs and interests; and (b) the distinct growing-up experiences of each cohort in a rapidly changing society. During routine times, youth and adults manage to cooperate or at least coexist. However, during certain extraordinary periods, specific historical conditions—especially a large educated youth cohort, institutional discontinuities, and opening-up eras—heighten young people’s dissatisfaction with society and desire for gradual reform or total change. These sociohistorical conditions, in conjunction with effective leadership and opportunities for youthful mobilization, facilitate the formation and spread of youth movements.

The dynamics of age-group mobilization involve the intensification of young people’s peer and generational identification. Adults and adult-run institutions are ‘deauthorized’ or chastised for the mistakes and disappointments they created in society, and young people ‘authorize’ or empower themselves to bring about or resist the desired change. As a youth movement becomes more active and visible, adult authorities typically react by attempting to curtail youthful protests, using either relatively peaceable methods or violence and repression. The wider adult population may support or oppose the youth movement activity and strongly influences its success or failure.

Once a youth movement challenges adult authority, intragenerational conflict erupts within the youth generation. That is, although young people may concur that society needs reform, youth groups are likely to disagree and compete over the direction, means, and extent of the proposed changes. During each historical generation, youth movements fighting for radical change are countered by youth groups defending the status quo or championing the status quo ante. Whether initiated by young people or sponsored by adults, extreme utopian as well as ideologically moderate generation units may organize that reflect an array and intensity of social and political views (revolutionary, progressive, moderate, conservative, and reactionary). The various opposing generation units compete over the control of the larger generational movement (Braungart and Braungart 1989a, 1989b, 1997).

4. The Impact Of Youth Movements

As youth movements unfold, the dynamics of interand intragenerational conflict sustain the momentum and largely determine how the movement is played out—as a positive source of societal renovation and renewal or fraught with injury, destruction, and death. Historically, youth movements have ranged from being mildly disruptive to thoroughly destabilizing; they have been short or long-lived; and they have been a significant force for extending democracy and citizenship as well as for totalitarian repression and genocide. Over the nineteenth and tweentieth centuries, youth movements have become a powerful means for young people to bring about or resist change in every part of the world.

With their personal identity and future tied to the vitality of the nation or state, young people readily are recruited into movements to reform or revolutionize society by charismatic leaders who are successful in connecting youthful life-course needs to movement objectives. Specific conditions and opportunities account for why youth movements erupt during particular periods in history. In all likelihood, future generations of young people will mobilize over issues that challenge their contemporaries. The question is not whether a new wave of youth movement activity will arise, but when and over what issues?

References:

- Braungart R G, Braungart M M 1989a Generational conflict and intergroup relations as the foundation for political generations. In: Lawler E J, Markovsky B (eds.) Advances in Group Processes. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, Vol. 6

- Braungart R G, Braungart M M 1989b Political generations. In: Braungart R G, Braungart M M M (eds.) Research in Political Sociology. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, Vol. 4

- Braungart R G, Braungart M M 1993 Historical generations and citizenship: 200 years of youth movements. In: Wasburn P C (ed.) Research in Political Sociology. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, Vol. 6

- Braungart R G, Braungart M M 1997 Why youth in youth movements? Mind & Human Interaction 8: 148–71

- Erikson E H 1968 Identity: Youth and Crisis, 1st edn. Norton, New York

- Esler A 1971 Bombs, Beards, and Barricades: 150 Years of Youth in Revolt. Stein and Day, New York

- Feuer L S 1969 The Conflict of Generations. Basic Books, New York

- Flacks R 1971 Youth and Social Change. Markham, Chicago

- Keniston K 1971 Youth and Dissent, 1st edn. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

- Mannheim K 1952 The problem of generations. In: Kecskemeti P (ed.) Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London

- Ortega Y, Gasset J 1962 Man and Crisis, 1st edn. Norton, New York

- Tilly C 1975 Revolutions and collective violence. In: Greenstein F I, Polsby N W (eds.) Handbook of Political Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, Vol. 3.