In all complex societies, the total stock of valued resources is distributed unequally, with the most privileged individuals and families receiving a disproportionate share of power, prestige, and other valued resources. The term ”stratification system” refers to the constellation of social institutions that generate observed inequalities of this sort. The key components of such systems are (1) the institutional processes that define certain types of goods as valuable and desirable, (2) the rules of allocation that distribute those goods across various positions or occupations (e.g., doctor, farmer, ”housewife”), and (3) the mobility mechanisms that link individuals to positions and generate unequal control over valued resources. The inequality of modern systems is thus produced by two conceptually distinct types of ”matching” processes: The jobs, occupations, and social roles in society are first matched to ”reward packages” of unequal value, and the individual members of society then are allocated to the positions defined and rewarded in that manner.

70 Social Stratification Research Paper Topics

- Age Prejudice and Discrimination

- Caste and Inherited Status

- Class and Race

- Class Conflict

- Class Consciousness

- Class, Status, and Power

- Culture of Poverty

- Discrimination

- Distinction and Stratification

- Distributive Justice

- Economic, Cultural, and Social Capital

- Educational Inequality

- Elite Culture

- Elites

- Employment Status Changes

- Equality of Opportunity

- Family Poverty

- Family Structure and Poverty

- Feminization of Poverty

- Gender and Stratification

- Gender Inequality/Stratification

- Gini Coefficient

- Global Income Inequality

- Health and Social Class

- Homelessness

- Horizontal and Vertical Mobility

- Inequality and the City

- Intergenerational and Intragenerational Mobility

- Intergenerational Mobility: Core Model of Social Fluidity

- Intergenerational Mobility: Methods of Analysis

- Leisure Class

- Life Chances and Resources

- Measuring the Effects of Mobility

- Meritocracy

- Middleman Minorities

- Modern Social Stratification

- New Middle Classes in Asia

- Occupational and Career Mobility

- Occupational Prestige

- Occupational Segregation

- Openness of Stratification Systems

- Partner Effects of Stratification

- Perceptions of Class

- Personality and Social Structure

- Politics and Stratification

- Poverty

- Privilege

- Professions

- Race/Ethnicity and Stratification

- Racial Hierarchy

- Residential Segregation

- Retrenchment of Welfare State

- Scaling of Occupations

- School Segregation and Desegregation

- Sex Based Wage Gap and Comparable Worth

- Slavery and Involuntary Servitude

- Social and Political Elites

- Social Inequality

- Social Security Systems

- Social Structure

- Societal Stratification

- Socioeconomic Status, Health, and Mortality

- Status Attainment

- Status Incongruence

- Stratification in Transition Economies

- Stratification, Technology, and Ideology

- Truth and Reconciliation Commissions

- Urban Poverty

- Wealth

- Wealth Inequality

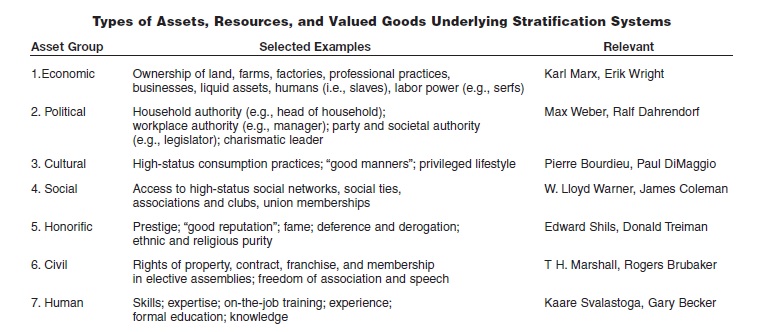

There are, of course, many types of rewards that come to be attached to social roles (see Table 1). The very complexity of modern reward systems arguably suggests a multidimensional approach to understanding stratification in which analysts specify the distribution of each of the valued goods listed in Table 1. Although some scholars have advocated a multidimensional approach of this sort, most have opted to characterize stratification systems in terms of discrete classes or strata whose members are similarly advantaged or disadvantaged with respect to various assets (e.g., property and prestige) that are deemed fundamental. In the most extreme versions of this approach, the resulting classes are assumed to be real entities that predate the distribution of rewards, and many scholars therefore refer to the ”effects” of class on the rewards that class members control (see the following section for details).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The goal of stratification research has thus devolved to describing the structure of these social classes and specifying the processes by which they are generated and maintained. The following types of questions are central to the field:

- What are the major forms of class inequality in human history? Is such inequality an inevitable feature of human life?

- How many social classes are there? What are the principal ”fault lines” or social cleavages that define the class structure? Are those cleavages strengthening or weakening with the transition to advanced industrialism?

- How frequently do individuals cross occupational or class boundaries? Are educational degrees, social contacts, and ”individual luck” important forces in matching individuals to jobs and class positions? What other types of social or institutional forces underlie occupational attainment and allocation?

- What types of social processes and state policies maintain or alter racial, ethnic, and sex discrimination in labor markets? Have these forms of discrimination been weakened or strengthened in the transition to advanced industrialism?

- Will stratification systems take on new and distinctive forms in the future? Are the stratification systems of modern societies gradually shedding their distinctive features and converging toward a common (i.e., postindustrial) regime?

These questions all adopt a critical orientation to human stratification systems that is distinctively modern in its underpinnings. For the greater part of history, the existing stratification order was regarded as an immutable feature of society, and the implicit objective of commentators was to explain or justify that order in terms of religious or quasi-religious doctrines. During with the Enlightenment, critical ”rhetoric of equality” gradually emerged and took hold, and the civil and legal advantages of the aristocracy and other privileged status groupings were accordingly challenged. After these advantages were largely eliminated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that egalitarian ideal was extended and recast to encompass not only such civil assets voting rights but also economic assets in the form of land, property, and the means of production. In its most radical form, this economic egalitarianism led to Marxist interpretations of human history, and it ultimately provided the intellectual underpinnings for socialism. While much of stratification theory has been formulated in reaction against these early forms of Marxist scholarship, the field shares with Marxism a distinctively modern (i.e., Enlightenment) orientation that is based on the premise that individuals are ”ultimately morally equal” (see Meyer 1994, p. 733; see also Tawney 1931). This premise implies that issues of inequality are critical in evaluating the legitimacy of modern social systems.

Table 1: Types of Assets, Resources, and Valued Goods Underlying Stratification Systems

Basic Concepts

The five questions outlined above cannot be addressed adequately without first defining some of the core concepts in the field. The following definitions are especially relevant:

- The degree of inequality in a given reward or asset (e.g., civil rights) depends on its dispersion or concentration across the individuals in the population. Although many scholars attempt to capture the overall level of societal inequality in a single parameter, such attempts obviously are compromised insofar as some types of rewards are distributed more equally than others are.

- The rigidity of a stratification system is characterized by the continuity over time in the social standing of its members. If the current wealth, power, or prestige of individuals can be predicted accurately on the basis of their prior statuses or those of their parents, then there is much class reproduction and the stratification system is accordingly said to be rigid.

- The process of stratification is ascriptive to the extent that traits present at birth (e.g., sex, race, ethnicity, parental wealth, nationality) influence the subsequent social standing of individuals. In modern societies, ascription of all kinds usually is seen as undesirable or ”discriminatory,” and much state policy is therefore directed toward fashioning a stratification system in which individuals acquire resources solely by means of their own achievements.

- The degree of status crystallization is characterized by the correlations among the assets listed in Table 1. If these correlations are strong, the same individuals (i.e., the ”upper class”) will consistently appear at the top of all status hierarchies, while other individuals (i.e., the ”lower class”) will consistently appear at the bottom of the stratification system.

These four variables can be used to characterize differences across societies in the underlying structure of stratification. As the discussion below reveals, there is great cross-societal variability not only in the types of inequality that serve as the dominant stratifying forces but also in the extent of such inequality and the processes by which it is generated, maintained, and reduced.

Forms of Social Stratification

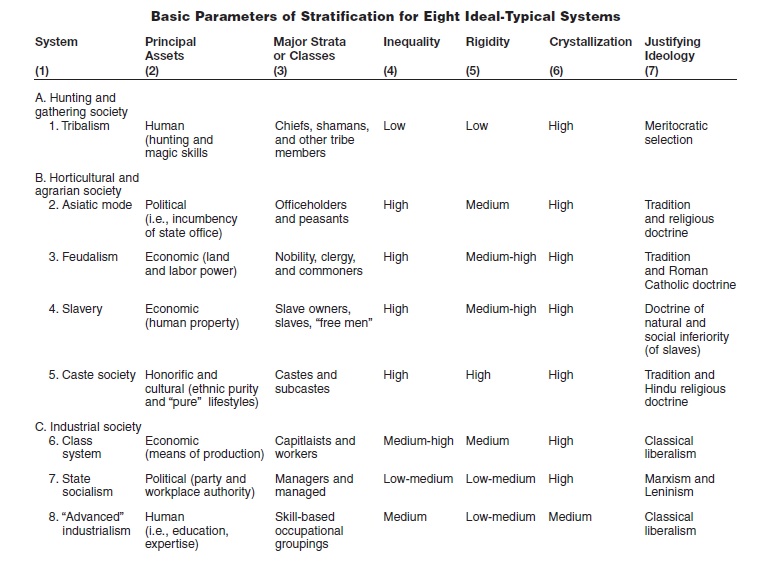

It is useful to begin with the purely descriptive task of classifying the various types of stratification systems that have appeared in past and present societies. Although the staple of modern classification efforts has been the tripartite distinction between class, caste, and estate (e.g., Svalastoga 1965), there is also a long tradition of Marxian typological work that introduces the additional categories of primitive communism, slave society, and socialism (Marx [1939] 1971; Wright 1985). As is shown in Table 2, these conventional approaches are largely but not entirely complementary, and it is therefore possible to fashion a hybrid classification that incorporates most of the standard distinctions (see Kerbo 1991 for related work).

For each of the stratification forms listed in Table 2, it is conventionally assumed that certain types of assets emerge as the dominant stratifying forces (see column 2) constitute the major axis around which social classes, strata, or status groupings are organized (see column 3). If this assumption holds, the rigidity of stratification systems can be indexed by the amount of class persistence (see column 5) and the degree of crystallization can be indexed by the correlation between class membership and each of the assets listed in Table 1 (see column 6). The final column in Table 2 rests on the further assumption that stratification systems have reasonably coherent ideologies that legitimate the rules and criteria by which individuals are allocated to positions in the class structure (see column 7).

The first panel in Table 2 pertains to the ”primitive” tribal systems that dominated human society from the beginning of human evolution until the Neolithic revolution of 10,000 years ago. Although tribal societies assumed various forms, the total size of the distributable surplus was in all cases limited, and this cap on the surplus placed corresponding limits on the overall level of economic inequality. Also, customs such as gift exchange, food sharing, and exogamy were practiced commonly in tribal societies and had some redistributive effects. In fact, many observers (e.g., Marx [1939] 1971) treated these societies as examples of ”primitive communism,” since the means of production (e.g., tools and land) were owned collectively and other types of property were distributed evenly among tribal members. This does not mean that a perfect equality prevailed; after all, the more powerful medicine men (i.e., shamans) often secured a disproportionate share of resources, and the tribal chief could exert considerable influence on political decisions. However, these residual forms of power and privilege were never inherited directly and typically were not allocated in accordance with such simple ascriptive traits as ethnicity, race, or clan. The main pathway to political office or high status and prestige was through superior skills in hunting, magic, or leadership (see Lenski 1966 for further details). While meritocratic forms of allocation often are seen as prototypically modern, they were present in an incipient form at very early stages of societal development.

Table 2: Basic Parameters of Stratification for Eight Ideal-Typical Systems

With the emergence of agrarian forms of production, the economic surplus became large enough to support more complex systems of stratification. The ”Asiatic mode,” which some commentators regard as a precursor of advanced agrarianism, is characterized by (1) the absence of strong legal institutions recognizing private property rights (with village life taking on a correspondingly communal character), (2) a state elite that extracts the surplus agricultural production through rents or taxes and expends it on ”defense, opulent living, and the construction of public works” (Shaw 1978, p. 127), and (3) a constant flux in elite personnel resulting from ”wars of dynastic succession and wars of conquest by nomadic warrior tribes” (O’Leary 1989, p. 18). This mode thus provides the conventional example of how a ”dictatorship of officialdom” can flourish in the absence of private property and a well-developed proprietary class. The parallel with modern socialism looms so large that various scholars have suggested that Marx downplayed the Asian case for fear of exposing it as a ”parable for socialism” (Gouldner 1980, pp. 324-352).

Whereas the institution of private property was underdeveloped in the East, the ruling class under Western feudalism was very much a propertied one. The distinctive feature of feudalism was the institution of personal bondage; that is, the nobility not only owned large estates, farms, or manors but also held legal title to the labor power of its serfs (Table 2, line B3). If a serf fled to the city, this was considered a form of theft: the serf was stealing the portion of his or her labor power owned by the lord (Wright 1985, p. 78). As such, the statuses of serf and slave differ only in degree, with slavery constituting the ”limiting case” in which workers lose all control over their own labor power (line B4). At the same time, it would be a mistake to reify this distinction, since the history of agrarian Europe reveals ”almost infinite gradations of subordination” (Bloch 1961, p. 256) that blur the conventional dividing lines between slavery, serfdom, and freedom. While the slavery of Roman society provides the best example of complete subordination, some slaves in the early feudal period were bestowed with ”rights” of real consequence (e.g., the right to sell surplus product), and some nominally free men were obliged to provide rents or services to a manorial lord. The social classes that emerged under European agrarianism thus were structured in quite diverse ways, but in all cases rights of property ownership were firmly established and the life chances of individuals were defined largely by their control over property in its differing forms. Unlike the ideal-typical Asiatic case, the nation-state was peripheral to the feudal stratification system, since the means of production (i.e., land and humans) were controlled by a proprietary class that emerged independently of the state.

The historical record shows that agrarian stratification systems were not always based on strictly hereditary forms of inequality (Table 2, panel B, column 5). The case of European feudalism is especially instructive in this regard, since it suggests that stratification systems often become more rigid as the underlying institutional forms mature and take shape (Mosca 1939; Kelley 1981). Although it is well known that feudalism after the twelfth century (i.e., ”classical feudalism”) was characterized by a ”rigid stratification of social classes” (Bloch 1961, p. 325), the feudal structure appears to have been more permeable in the period before the institutionalization of the manorial system and the associated transformation of the nobility into a legal class. In this transitionary period, access to the nobility was not legally restricted to the offspring of nobility and marriage across classes or estates was not prohibited, at least not formally. The case of ancient Greece provides a complementary example of a relatively open agrarian society. As Finley (1960) and others have noted, the condition of slavery was heritable under Greek law, yet manumission (the freeing of slaves) was so common that the slave class had to be replenished constantly with new captives secured through war or piracy.

The most extreme examples of hereditary closure are found in caste societies (Table 2, line B5). While some scholars have argued that American slavery had ”caste-like features” (Berreman 1981), it is Hindu India which clearly provides the defining case of caste organization. The Indian caste system is based on (1) a hierarchy of status groupings (i.e., castes) that are ranked by ethnic purity, wealth, and access to goods or services, (2) a corresponding set of ”closure rules” that forbid all forms of intercaste marriage or mobility and thus make caste membership both hereditary and permanent, (3) a high degree of physical and occupational segregation enforced by elaborate rules and rituals governing intercaste contact, and (4) ajusti-fying ideology (Hinduism) that successfully induces the population to regard such extreme forms of inequality as legitimate and appropriate. What makes this system distinctive is not only its well-developed closure rules but also the fundamentally honorific (and noneconomic) character of the underlying social hierarchy. As is indicated in Table 2, the castes of India are ranked on a continuum of ethnic and ritual purity, with the highest positions in the system reserved for castes that prohibit behaviors that are seen as dishonorable or ”polluting.” In some circumstances, castes that acquired political and economic power eventually advanced in the status hierarchy, yet they usually did so after mimicking the behaviors and lifestyles of higher castes.

The defining feature of the industrial era (Table 2, panel C) has been the emergence of egalitarian ideologies and the consequent ”delegitimation” of the extreme forms of stratification found in caste, feudal, and slave systems. This can be seen in the European revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that pitted the egalitarian ideals of the Enlightenment against the privileges of rank and the political power of the nobility. In the end, these struggles eliminated the last residue of feudal privilege, but they also made new types of inequality and stratification possible. Under the class system that ultimately emerged (line C6), the estates of the feudal era were replaced by purely economic groups (i.e., ”classes”) and the old closure rules based on hereditary principles were supplanted by formally meritocratic processes. The resulting classes were neither legal entities nor closed status groupings; consequently, the emergent class-based inequalities could be represented and justified as the natural outcome of economic competition among individuals with differing abilities, motivation, or moral character (i.e., ”classical liberalism”). This class structure had such a clear ”economic base” (Kerbo 1991, p. 23) that Marx ([1894] 1972) of course defined classes in terms of their relationship to the means of economic production. The precise contours of the industrial class structure are nonetheless a matter of continuing debate; for example, a simple (”vulgar”) Marxian model focuses on the cleavage between capitalists and workers, whereas more refined Marxian and neo-Marxian models identify additional intervening or ”contradictory” classes (Wright 1985) and other (non-Marxian) approaches represent the class structure as a continuous gradation of socioeconomic status or ”monetary wealth and income” (Mayer and Buckley 1970, p. 15).

Regardless of the relative merits of these models, the ideology underlying the socialist revolutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was explicitly Marxist. The intellectual heritage of these revolutions and their legitimating ideologies ultimately can be traced to the Enlightenment; that is, the egalitarianism of the Enlightenment was still very much in force, but now it was deployed against the economic power of the capitalist class rather than against the status and honorific privileges of the nobility. The evidence from eastern Europe and elsewhere suggests that these egalitarian ideals were only partially realized. In the immediate postrevolutionary period, factories and farms were collectivized or socialized and fiscal and economic reforms were instituted expressly to reduce income inequality and wage differentials among manual and nonmanual workers. Although these egalitarian policies subsequently were weakened or reversed through the reform efforts of Stalin and others, this does not mean that inequality on the scale of prerevolutionary society was ever reestablished among rank-and-file workers. At the same time, it has long been argued that the socialization of productive forces did not have the intended effect of empowering workers, since the capitalist class was replaced by a ”new class” of party officials and managers who continued to control the means of production and allocate the resulting social surplus. This class has been variously identified with intellectuals or the intelligentsia (e.g., Gouldner 1979), bureaucrats or managers (e.g., Rizzi 1985), and party officials or appointees (e.g., Djilas 1965). Whatever the formulation adopted, the assumption is that the working class ultimately lost out in contemporary socialist revolutions, just as it did in the so-called bourgeois revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Whereas the means of production were socialized in the revolutions in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the capitalist class remained largely intact throughout the process of industrialization in the West. The old propertied class may, however, be weakening in the West and the East alike as a postindustrial service economy diffuses and technical expertise emerges as a ”new form of property” (Berg 1973, p. 183). It follows that human and cultural capital may be replacing economic capital as the principal stratifying force in advanced industrial society (Table 2, line C8). According to Gouldner (1979) and others (e.g., Galbraith 1967), a dominant class of cultural elites is emerging in the West, much as the transition to state socialism allegedly generated a new class of intellectuals in the East. This does not mean that all theorists of advanced industrialism posit a grand divide between the cultural elite and a working mass. In fact, some commentators (e.g., Dahrendorf 1959, pp. 48-57) have argued that skill-based cleavages are crystallizing throughout the occupational structure, resulting in a continuous gradation or hierarchy of socioeconomic classes. In nearly all models of advanced industrial society, it is further assumed that education is the principal mechanism by which individuals are sorted into such classes, and educational institutions thus serve in this context to ”license” human capital and convert it to cultural currency.

Sources of Social Stratification

Although the preceding sketch indicates that a wide range of stratification systems emerged over the course of human history, it remains unclear whether some form of stratification or inequality is an inevitable feature of human society. In addressing this question, it is useful to consider the functionalist theory of Davis and Moore (1945), which is the best-known attempt to understand ”the universal necessity which calls forth stratification in any system” (p. 242). The starting point for any functionalist approach is the premise that all societies must devise some means to motivate the best workers to fill the most important and difficult occupations. This ”motivational problem” can be addressed in a variety of ways, but the simplest solution may be to construct a hierarchy of rewards (e.g., prestige, property, power) that privileges the incumbents of functionally significant positions. As noted by Davis and Moore (1945, p. 243), this amounts to setting up a system of institutionalized inequality (i.e., a ”stratification system”), with the occupational structure serving as a conduit through which unequal rewards and perquisites are disbursed. The stratification system therefore may be seen as an ”unconsciously evolved device by which societies insure that the important positions are conscientiously filled by the most qualified persons” (Davis and Moore 1945, p. 243). Under the Davis-Moore formulation, it is claimed that some form of inequality is needed to allocate labor efficiently, but no effort is made to specify how much inequality is sufficient for this purpose. The extreme forms of stratification found in existing societies may well exceed the ”minimum . . . necessary to maintain a complex division of labor” (Wrong 1959, p. 774).

The Davis-Moore hypothesis has come under criticism from several quarters. The prevailing view among postwar commentators is that the original hypothesis cannot adequately account for inequalities in ”stabilized societies where statuses are ascribed” (Wesolowski 1962, p. 31). Whenever vacancies in the occupational structure are allocated on purely hereditary grounds, there is no need to attend to the ”motivational problems” that Davis and Moore (1945) emphasized, and one cannot reasonably argue that the reward system is serving its putative function of matching qualified workers to important positions. It must be recognized, however, that a purely hereditary system is rarely achieved in practice; in fact, even in the most rigid caste societies, talented and qualified individuals typically have some opportunities for upward mobility. Under the Davis-Moore formulation (1945), this slow trickle of mobility is regarded as so essential to the functioning of the social system that elaborate systems of inequality have evidently been devised to ensure that the trickle continues. Although the Davis-Moore hypothesis therefore can be used to explain stratification in societies with some mobility, the original hypothesis becomes wholly untenable in societies with complete closure (if such societies could be found).

The functionalist approach also has been criticized for neglecting the ”power element” in stratification systems. It has long been argued that Davis and Moore (1945) failed ”to observe that incumbents [of functionally important positions] have the power not only to insist on payment of expected rewards but to demand even larger ones” (Wrong 1959, p. 774). In this regard, the stratification system may be seen as self-reproducing: The holders of important positions can use their power to influence the distribution of resources and preserve or extend their own privileges. It would be difficult, for instance, to account fully for the advantages of feudal lords without referring to their ability to enforce their claims through moral, legal, and economic sanctions. The distribution of rewards thus reflects not only the ”latent needs” of the larger society but also the balance of power among competing groups and their members.

Whereas the early debates addressed conceptual issues of this kind, subsequent researchers shifted their emphasis to constructing ”critical tests” of the Davis-Moore hypothesis. This research effort continued throughout the 1970s, with some commentators reporting evidence consistent with functionalist theorizing (e.g., Cullen and Novick 1979) and others providing less sympathetic assessments (e.g., Broom and Cushing 1977). The 1980s was a period of relative quiescence, but Lenski (1994) recently reopened the debate by suggesting that ”many of the internal, systemic problems of Marxist societies were the result of inadequate motivational arrangements” (p. 57). That is, Lenski argues that the socialist commitment to wage leveling made it difficult to recruit and motivate highly skilled workers, while the ”visible hand” of the socialist economy could never be calibrated to mimic adequately the natural incentive of capitalist profit taking. These results lead Lenski to conclude that ”successful incentive systems involve . . . motivating the best qualified people to seek the most important positions” (p. 59). It remains to be seen whether this reading of the socialist ”experiments in destratification” (Lenski 1978) will generate a new round of functionalist theorizing and debate.

The Structure of Modern Stratification

The recent history of stratification theory is in large part a history of debates about the contours of class, status, and prestige hierarchies in advanced industrial societies. These debates may appear to be nothing more than academic infighting, but among the participants they are treated as a ”necessary prelude to the conduct of political strategy” (Parkin 1979, p. 16). For instance, considerable energy has been devoted to drawing the correct dividing line between the working class and the bourgeoisie, since the task of identifying the oppressed class is seen as a prerequisite to devising a political strategy that might appeal to it. In such mapmaking efforts, political and intellectual goals are often conflated and debates in the field are accordingly infused with more than the usual amount of scholarly contention. While these debates are complex and wide-ranging, it will suffice here to distinguish between four major schools of thought.

Marxists and Post-Marxists

The debates within the Marxist and neo-Marxist camps have been especially contentious not only as a result of such political motivations but also because the discussion of class in Capital (Marx [1894] 1972) is too fragmentary and unsystematic to adjudicate between competing interpretations. At the end of the third volume of Capital, one finds the famous fragment on ”the classes” (Marx [1894] 1972, pp. 862-863), but this discussion breaks off at the point where Marx appeared to be ready to advance a formal definition of the term. It is clear, nonetheless, that his abstract model of capitalism was resolutely dichotomous, with the conflict between capitalists and workers constituting the driving force behind further social development. This simple two-class model should be viewed as an ideal type designed to capture the developmental tendencies of capitalism; after all, whenever Marx carried out concrete analyses of existing capitalist systems, he acknowledged that the class structure was complicated by the persistence of transitional classes (i.e., landowners), quasi-class groupings (e.g., peasants), and class fragments (e.g., the lumpen proletariat). It was only with the progressive maturation of capitalism that Marx expected these complications to disappear as the ”centrifugal forces of class struggle and crisis flung all dritte Personen [third persons] to one camp or the other” (Parkin 1979, p. 16).

The recent history of modern capitalism suggests that the class structure has not evolved in such a precise and tidy fashion. As Dahrendorf (1959) points out, the old middle class of artisans and shopkeepers has declined in relative size, yet a new middle class of managers, professionals, and nonmanual workers has expanded to occupy the vacated space. The last fifty years of neo-Marxist theorizing can be seen as the intellectual fallout from this development, with some commentators attempting to minimize its implications and others putting forward a revised mapping of the class structure that explicitly accommodates the new middle class. In the former camp, the principal tendency is to claim that the lower sectors of the new middle class are in the process of being proletarianized, since ”capital subjects [nonmanual labor] … to the forms of rationalization characteristic of the capitalist mode of production” (Braverman 1974, p. 408). This line of reasoning suggests that the working class may gradually expand in relative size and therefore regain its earlier power.

At the other end of the continuum, Poulantzas (1974) has argued that most members of the new intermediate stratum fall outside the working class proper, since they are not exploited in the classical Marxian sense (i.e., surplus value is not extracted). This approach may have the merit of keeping the working class conceptually pure, but it reduces its size to ”pygmy proportions” (see Parkin 1979, p. 19), and hence dashes the hopes of those who see workers as a viable political force in advanced industrial society. There is, then, much interest in developing class models that fall between the extremes advocated by Braverman (1974) and Poulantzas (1974). For example, the neo-Marxist model proposed by Wright (1978) describes an American working class that is acceptably large (approximately 46 percent of the labor force), yet the class mappings in this model still pay tribute to the various cleavages and divisions among workers who sell their labor power. That is, professionals are placed in a distinct ”semi-autonomous class” by virtue of their control over the work process, while upper-level supervisors are located in a ”managerial class” by virtue of their authority over workers (Wright 1978). The dividing lines proposed in this model thus rest on concepts (e.g., autonomy and authority relations) that once were purely the province of Weberian or neo-Weberian sociology. As Parkin (1979) puts it, ”inside every neo-Marxist there seems to be a Weberian struggling to get out” (p. 25).

These early class models, which once were quite popular, have been superseded by various second-generation models that rely more explicitly on the concept of exploitation. In effect, Roemer (1988) and others (Wright 1997; S0rensen 1996) have redefined exploitation as the extraction of ”rent,” which refers to the excess earnings that are secured by limiting access to positions and thus artificially restricting the supply of qualified labor. If an approach of this sort is adopted, one can test for skill-based exploitation by calculating whether the cumulated lifetime earnings of skilled laborers exceed those of unskilled laborers by an amount larger than the implied training costs (e.g., school tuition and forgone earnings). In a perfectly competitive market, labor will flow to the most rewarding occupations, equalizing the lifetime earnings of workers and eliminating exploitative returns. However, when opportunities are limited by the imposition of restrictions on entry (e.g., qualifying examinations), the equilibrating flow of labor is disrupted and the potential for exploitation emerges. By implication, the working class can no longer be viewed as a wholly cohesive and unitary force, as some workers presumably have an interest in preserving and extending the institutional mechanisms (e.g., schools) that allow them to reap exploitative returns.

Weberians and Post-Weberians

The rise of the ”new middle class” has proved less problematic for scholars working within a Weberian framework. Indeed, the class model advanced by Weber suggests a multiplicity of class cleavages, since it equates the economic class of workers with their ”market situation” in the competition forjobs and valued goods (Weber [1922] 1968, pp. 926-40). In this formulation, the class of skilled workers is privileged because its incumbents are in high demand on the labor market and because its economic power can be parlayed into high wages, job security, and an advantaged position in commodity markets (Weber [1922] 1968, pp. 927-928). At the same time, the stratification system is complicated by the existence of ”status groupings,” which Weber saw as forms of social affiliation that can compete, coexist, or overlap with class-based groupings. Although an economic class is merely an aggregate of individuals in a similar market situation, a status grouping is defined as a community of individuals who share a style of life and interact as status equals (e.g., the nobility, an ethnic caste). In some circumstances, the boundaries of a status grouping are determined by purely economic criteria, yet Weber notes that ”status honor normally stands in sharp opposition to the pretensions of sheer property” (Weber [1922] 1968, p. 932).

The Weberian approach has been elaborated and extended by sociologists attempting to understand the ”American form” of stratification. In the postwar decades, American sociologists typically dismissed the Marxist model of class as overly simplistic and one-dimensional, whereas they celebrated the Weberian model as properly distinguishing between the numerous variables Marx had conflated in his approach. These scholars often disaggregated the stratification dimensions identified by Weber into a multiplicity of variables (e.g., income, education, ethnicity) and then showed that the correlations between those variables were weak enough to generate various forms of ”status inconsistency” (e.g., a poorly educated millionaire). The resulting picture suggested a ”pluralistic model” of stratification; that is, the class system was represented as intrinsically multidimensional, with a host of cross-cutting affiliations producing a complex patchwork of internal class cleavages. While one critic has remarked that the multidimensionalists provided a ”sociological portrait of America as drawn by Norman Rockwell” (Parkin 1979, p. 604), some post-Weberians also emphasized the ”seamy side” of pluralism. In fact, Lenski (1954) and others (e.g., Lipset 1959) have argued that modern stratification systems can be seen as breeding grounds for personal stress and political radicalism, since individuals with contradictory statuses may feel relatively deprived and thus support ”movements designed to alter the political status quo” (Lenski 1966, p. 88). This line of research died out in the early-1970s under the force of negative and inconclusive findings (Jackson and Curtis 1972). Althoughthere has been a resurgence of theorizing about issues of status disparity and relative deprivation (e.g., Baron 1994), much of this work focuses on the generic properties of all ”post modern” stratification systems rather than the allegedly exceptional features of the American case.

In recent years, the standard multidimensionalist interpretation of ”Class, Status, and Party” (Weber 1946, pp. 180-95) has fallen into disfavor, and an alternative version of neo-Weberian stratification theory has gradually taken shape. This revised reading of Weber draws on the concept of social closure as defined and discussed in the essay ”Open and Closed Relationships” (Weber [1922] 1968, pp. 43-46; 341-348). By social closure, Weber is referring to the processes by which groups devise and enforce rules of membership, typically with the objective of improving the position [of the group] by monopolistic tactics” (Weber [1922] 1968, p. 43). While Weber does not directly link this discussion with his other contributions to stratification theory, later commentators pointed out that social classes and status groupings are generated by simple exclusionary processes operating at the macro-structural level (e.g., Giddens 1973). Under modern industrialism, there are obviously no formal sanctions that prevent labor from crossing class boundaries, yet various institutional forces (e.g., private property, union shops) are quite effective in limiting the amount of class mobility over the life course and between generations. These exclusionary mechanisms not only ”maximize claims to rewards and opportunities” among the members of closed classes (Parkin 1979, p. 44), but also provide the demographic continuity needed to generate distinctive class cultures and ”reproduce common life experience over the generations” (Giddens 1973, p. 107). As is noted by Giddens (1973, pp. 107-12), barriers of this sort are not the only source of ”class structuration,” yet they clearly play a contributing role in the formation of identifiable classes under modern industrialism. This revisionist interpretation of Weber has reoriented the discipline toward examining the causes and sources of class formation rather than the potentially fragmenting effects of cross-cutting affiliations and cleavages.

Gradational Status Groupings

The theorists discussed above have all proceeded by mapping individuals or families into mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories (”classes”). As this review indicates, there continues to be much debate about the location of the boundaries separating these categories, yet the shared assumption is that fundamental class boundaries of some kind are present, if only in a latent or incipient form. By contrast, the implicit claim underlying gradational approaches is that such ”dividing lines” are largely the construction of overzealous sociologists and that the underlying structure of modern stratification can be more closely approximated with gradational measures of income, status, or prestige. The standard concepts of class action and consciousness are similarly discarded; that is, whereas most categorical models are based on the (realist) assumption that the constituent categories are ”structures of interest that provide the basis for collective action” (Wright 1979, p. 7), gradational models usually are represented as taxonomic or statistical classifications of purely heuristic interest.

This approach has been pursued in various ways, but typically not by operationalizing social standing in terms of income alone. It does not follow that distinctions of income are sociologically uninteresting; in fact, if one is intent on assessing the ”market situation” of workers (Weber [1922] 1968), there is much to recommend a direct measurement of their income and wealth. The preferred approach has nonetheless been to define classes as ”groups of persons who are members of effective kinship units which, as units, are approximately equally valued” (Parsons 1954, p. 77). This formulation was first operationalized in postwar community studies (e.g., Warner 1949) by constructing broadly defined categories of reputational equals (”upper upper class,” ”upper middle class,” etc.). However, when the disciplinary focus shifted to the national stratification system, the measure of choice soon became occupational scales of prestige (e.g., Treiman 1977), socioeconomic status (e.g., Blau and Duncan 1967), or global ”success in the labor market” (Jencks et al. 1988). Although there is much debate about the usefulness of such scales, they continue to serve as standard measures of class background in sociological research of all kinds.

Generating Social Stratification

The language of stratification theory makes a sharp distinction between the distribution of social rewards (e.g., the income distribution) and the distribution of opportunities for securing those rewards. As sociologists have noted, it is the latter distribution that governs popular judgments about the legitimacy of stratification: the typical American, for example, is willing to tolerate substantial inequalities in power, wealth, or prestige if the opportunities for securing those social goods are distributed equally across all individuals. Whatever the wisdom of this popular logic, stratification researchers have long explored its factual underpinnings by describing and explaining the structure of mobility chances.

The study of social mobility is, then, a major sociological industry. The relevant literature is vast, yet much of this work can be classified into one of three traditions of scholarship.

- The conventional starting point has been to analyze bivariate ”mobility tables” formed by cross-classifying the occupational origins and destinations of individuals. These tables can be used to estimate the densities of occupational inheritance, describe patterns of mobility and exchange between occupations, and map the social distances between classes and their constituent occupations. Moreover, when comparable mobility tables are assembled for several countries, it becomes possible to address long-standing debates about the underlying contours of cross-national variation in stratification systems (e.g., Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992).

- It is a sociological truism that Blau and Duncan (1967) and their colleagues (e.g., Sewell et al. 1969) revolutionized the field with their formal ”path models” of stratification. These models were intended to represent, if only partially, the process by which background advantages can be converted into socioeconomic status through the mediating variables of schooling, aspirations, and parental encouragement. Under formulations of this kind, the main sociological objective was to show that socioeconomic outcomes are structured not only by ”native ability” and family origins but also by various intervening variables (e.g., schooling) that are themselves only partly determined by origins, race and gender, and other ascriptive forces (Blau and Duncan 1967, pp. 199-205). This line of research, which had fallen out of favor by the mid-1980s, has been rediscovered and revived as stratification scholars react to the now-fashionable argument (i.e., Herrnstein and Murray 1994) that inherited intelligence is increasingly determinative of stratification outcomes.

- These ”status attainment” models have been criticized for failing to attend to the social structural constraints that operate on the stratification process independently of individual-level traits. The structuralist accounts that ultimately emerged from these critiques amounted in most cases to refurbished versions of the dual economy and market segmentation models that were introduced and popularized several decades ago by institutional economists. When these models were redeployed by sociologists in the early 1980s, the usual objective was to demonstrate that women and minorities were disadvantaged not only because of deficient investments in human capital (e.g., inadequate schooling and experience) but also by their consignment to ”secondary” labor markets that on average paid lower wages and offered fewer opportunities for promotion or advancement.

These three approaches to stratification analysis typically are implemented with quantitative models of the most sophisticated sort. In a classic critique, Coser (1975) suggested that stratification researchers were so entranced by quantitative models of mobility, attainment, and dissimination that ”the methodological tail was wagging the substantive dog” (p. 652). This latter argument can no longer be taken exclusively in the intended pejorative sense because new models and methods have raised important substantive questions that previously had been overlooked. In this sense, The development of structural equation, log-linear, and event history models are properly viewed as watershed events in the history of mobility research.

Ascriptive Processes

The forces of race and gender have long been relegated to the sociological sidelines by class theorists of both Marxist and non-Marxist persuasions. In most versions of class-analytic theory, status groups are treated as secondary forms of affiliation, whereas class-based ties are seen as more fundamental and decisive determinants of social and political action. Although Race and gender have not been ignored altogether in such treatments, they typically are represented as vestiges of traditional loyalties that will wither away under the rationalizing influence of socialism, industrialism, or modernization.

The first step in the intellectual breakdown of this model was the fashioning of a multidimensional approach to stratification. Whereas many class theorists gave theoretical or conceptual priority to the economic dimension of stratification, the early multidimensionalists emphasized that social behavior could be understood only by taking into account all status group memberships (e.g., race, gender) and the complex ways in which they interact with one another and with class outcomes. The class-analytic approach was further undermined by the apparent reemergence of racial, ethnic, and nationalist conflicts in the late postwar period. Far from withering away under the force of industrialism, the bonds of race and ethnicity seemed to be alive and well: The modern world was witnessing a ”sudden increase in tendencies by people in many countries and many circumstances to insist on the significance of their group distinctiveness” (Glazer and Moynihan 1975, p. 3). This resurgence of status politics continues today. In one last several decades, ethnic and regional solidarities have intensified with the decline of conventional class politics in central Europe and elsewhere, and gender-based affiliations and loyalties have strengthened as feminist movements diffuse throughout much of the modern world.

This turn of events has led some commentators to proclaim that the factors of race, ethnicity, and gender are now the driving force behind the evolution of stratification systems. In one such formulation, Glazer and Moynihan (1975) conclude that ”property relations [formerly] obscured ethnic ones” (p. 16), but now it is ”property that begins to seem derivative, and ethnicity that becomes a more fundamental source of stratification” (p. 17). The analogous position favored by some feminists is that ”men’s dominance over women is the cornerstone on which all other oppression (class, age, race) rests” (Hartmann 1981, p. 12; see also Firestone 1972). This formulation begs the question of timing; that is, if the forces of gender or ethnicity are truly primordial, it is natural to ask why they began expressing themselves with real vigor in more recent history. In addressing this issue, Bell (1975) suggests that a trade-off exists between class-based and ethnic forms of solidarity, with the latter strengthening whenever the former weaken. As the conflict between labor and capital is institutionalized (via ”trade unionism”), Bell argues, class-based affiliations typically lose their affective content and workers must turn to racial or ethnic ties to provide them with a renewed sense of identification and commitment. It could be argued that gender politics often fill the same ”moral vacuum” that this decline in class politics has allegedly generated.

It may be misleading to treat the competition between ascriptive and class-based forces as a sociological horse race that only one of the two principles can ultimately win. In a pluralist society of the American kind, workers can choose an identity appropriate to the situational context; a modern-day worker may behave as ”an industrial laborer in the morning, a black in the afternoon, and an American in the evening” (Parkin 1979, p. 34). Although this situational model of status has not been adopted widely in contemporary research, there is some evidence of renewed interest in conceptualizing the diverse affiliations of individuals and the ”multiple oppressions” (see Wright 1989, pp. 5-6) that those affiliations engender. It is now fashionable, for example, to assume that the major status groupings in contemporary stratification systems are defined by the intersection of ethnic, gender, and class affiliations (e.g., black working-class women, white middle-class men). The theoretical framework for this approach is not always well articulated, but the implicit claim seems to be that these subgroupings shape the ”life chances and experiences” of individuals (Ransford and Miller 1983, p. 46) and thus define the social settings in which subcultures typically emerge. The obvious effect is to invert the traditional post-Weberian perspective on status groupings; that is, whereas orthodox multidimensionalists described the stress experienced by individuals with inconsistent statuses (e.g., poorly educated doctors), the new multidimensionalists emphasize the shared interests and cultures generated within commonly encountered status sets (e.g., black working-class women).

The sociological study of gender, race, and ethnicity has thus burgeoned. As is noted by Lieberson (1994, p. 649), there has been a certain faddishness in the types of research topics that scholars of gender and race have chosen for study, with the resulting body of literature having a correspondingly haphazard and scattered feel. The following research questions have nonetheless emerged as relatively central ones in the field:

- How are class relations affected by ascriptive forms of stratification? Can capitalists exploit ethnic antagonisms and patriarchy to their advantage? Do male and majority group workers also benefit from stratification by gender and race?

- What accounts for variability across time and space in ethnic conflict and solidarity? Will ethnic loyalties weaken as modernization diffuses across ethnically diverse populations? Does modernization instead produce a ”cultural division of labor” that strengthens communal ties by making ethnicity the principal arbiter of life chances? Is ethnic conflict further intensified when ethnic groups compete for the same niche in the occupational structure?

- What are the generative forces underlying ethnic, racial, and gender differentials in income and other socioeconomic outcomes? Do those differentials proceed from supply-side variability in the occupational aspirations or the human capital workers bring to the market? Alternatively, are they produced by demand-side forces such as market segmentation, statistical or institutional discrimination, and the seemingly irrational tastes and preferences of employers?

- Is theunderlying structure of ascriptive stratification changing with the transition to advanced industrialism? Does the ”logic” of industrialism require universalistic personnel practices and consequent declines in overt discrimination? Can this logic be reconciled with the rise of a modern ghetto underclass, the persistence of massive segregation by sex and race, and the emergence of new forms of poverty and hardship among women and recent immigrants?

These questions make it clear that ethnic, racial, and gender inequalities often are classed together and treated as analytically equivalent forms of ascription. Although Parsons (1951) and others (e.g., Tilly 1998) have emphasized the shared features of ”communal ties,” such ties can be maintained (or subverted) in very different ways. It has long been argued, for example, that some forms of inequality can be rendered more palatable by the practice of pooling resources (e.g., income) across family members. As Lieberson (1994) points out, the family operates to bind males and females together in a single unit of consumption, whereas extrafamilial institutions (schools, labor markets, etc.) must be relied on to provide the same integrative functions for ethnic groups. If these functions are left wholly unfilled, one might expect ethnic separatist and nationalist movements to emerge. The same ”nationalist” option is obviously less viable for single-sex groups; indeed, barring any revolutionary changes in family structure or kinship relations, it seems unlikely that separatist solutions will ever garner much support among men or women. These considerations may account for the absence of a well-developed literature on overt conflict between single-sex groups.

Conclusions

In recent years, criticisms of the class-analytic framework have escalated, with many scholars arguing that the concept of class is ”ceasing to do any useful work for sociology” (Pahl 1989, p. 710). Although such postmodern accounts have taken many forms, most proceed from the assumption that social classes no longer definitively structure lifestyles and life chances and that ”new theories, perhaps more cultural than structural, [are] in order” (Davis 1982, p. 585). In accounts of this sort, the labor movement is represented as a fading enterprise rooted in the old conflicts of the workplace and industrial capitalism, whereas new social movements (e.g., environmentalism) are assumed to provide a more appealing call for collective action by virtue of their emphasis on issues of lifestyle, personal identity, and normative change.

This argument has not been subjected to convincing empirical tests and may prove to be premature. However, even if lifestyles and life chances are truly ”decoupling” from economic class, this should not be misunderstood as a more general decline in stratification per se. The massive facts of economic, political, and honorific inequality will still be operative even if conventional models of class ultimately are found deficient in characterizing the postmodern condition. As is well known, some forms of inequality have increased in recent years (e.g., income inequality), while others show no signs of disappearing or withering away (e.g., political inequality).

This persistence and in some cases deepening of inequality is coupled with the continuing diffusion of antistratification values and a correspondingly heightened sensitivity to all things unequal. As egalitarianism spreads, the postmodern public becomes heavily involved in monitoring and exposing illegitimate (i.e., nonmeritocratic) forms of stratification, and even small departures from equality are increasingly viewed as problematic and intolerable (Meyer 1994). Moreover, because stratification systems are deeply institutionalized, there is good reason to anticipate that demands for egalitarian change will outpace actual changes in stratification practices. These dynamics imply that issues of stratification will continue to generate discord and conflict even in the unlikely event of a long-term trend toward diminishing inequality.

References:

- Baron, James N. 1994 ‘‘Reflections on Recent Generations of Mobility Research.’’ In David B. Grusk, ed., Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

- Bell, Daniel 1975 ‘‘Ethnicity and Social Change.’’ In Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan, eds., Ethnicity: Theory and Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Berg, Ivar 1973 Education and Jobs: The Great Training Robbery. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

- Berreman, Gerald 1981 Caste and Other Inequities. Delhi: Manohar.

- Blau, Peter M., and Otis Dudley Duncan 1967 The American Occupational Structure. New York: Wiley.

- Bloch, Marc 1961 Feudal Society. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Braverman, Harry 1974 Labor and Monopoly Capital. New York and London: Monthly Review Press.

- Broom, Leonard, and Robert G. Cushing 1977 ‘‘A Modest Test of an Immodest Theory: The Functional Theory of Stratification.’’ American Sociological Review 42:157–169.

- Coser, Lewis A. 1975 ‘‘Presidential Address: Two Methods in Search of a Substance.’’ American Sociological Review 40:691–700.

- Cullen, John B., and Shelley M. Novick 1979 ‘‘The Davis- Moore Theory of Stratification: A Further Examination and Extension.’’ American Journal of Sociology 84:1424–1437.

- Dahrendorf, Ralf 1959 Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

- Davis, James 1982 ‘‘Achievement Variables and Class Cultures: Family, Schooling, Job, and Forty-Nine Dependent Variables in the Cumulative GSS.’’ American Sociological Review 47:69–86.

- Davis, Kingsley, and Wilbert E. Moore 1945 ‘‘Some Principles of Stratification.’’ American Sociological Review 10:242–249.

- Djilas, Milovan 1965 The New Class. New York: Praeger.

- Erikson, Robert, and John H. Goldthorpe 1992 The Constant Flux: A Study of Class Mobility in Industrial Societies. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Finley, Moses J. 1960 Slavery in Classical Antiquity. Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer and Sons.

- Firestone, Shulamith 1972 The Dialectic of Sex. New York: Bantam.

- Galbraith, John K. 1967 The New Industrial State. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Giddens, Anthony 1973 The Class Structure of the Advanced Societies. London: Hutchinson.

- Glazer, Nathan, and Daniel P. Moynihan 1975 ‘‘Introduction.’’ In Nathan Glazer and Daniel P. Moynihan, eds., Ethnicity: Theory and Experience. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Gouldner, Alvin 1979 The Future of Intellectuals and the Rise of the New Class. New York: Seabury.

- Gouldner, Alvin 1980 The Two Marxisms: Contradictions and Anomalies in the Development of Theory. New York: Seabury Press.

- Hartmann, Heidi 1981 ‘‘The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism: Towards a More Progressive Union.’’ In Lydia Sargent, ed., Women and Revolution. Boston: South End Press.

- Herrnstein, Richard J., and Charles Murray 1994 The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press.

- Jackson, Elton F., and Richard. F. Curtis 1972 ‘‘Effects of Vertical Mobility and Status Inconsistency: A Body of Negative Evidence.’’ American Sociological Review 37:701–13.

- Jencks, Christopher, Lauri Perman, and Lee Rainwater 1988 ‘‘What Is a Good Job? A New Measure of Labor-Market Success.’’ American Journal of Sociology 93:1322–1357.

- Kelley, Jonathan 1981 Revolution and the Rebirth of Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kerbo, Harold R. 1991 Social Stratification and Inequality: Class Conflict in Historical and Comparative Perspective. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lenski, Gerhard E. 1954 ‘‘Status Crystallization: A Non- Vertical Dimension of Social Status.’’ American Sociological Review 19:405–413.

- Lenski, Gerhard E. 1966 Power and Privilege. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lenski, Gerhard E. 1978 ‘‘Marxist Experiments in Destratification: An Appraisal.’’ Social Forces 57:364–383.

- Lenski, Gerhard E. 1994 ‘‘New Light on Old Issues: The Relevance of ‘Really Existing Socialist Societies’ for Stratification Theory.’’ In David B. Grusky, ed., Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Boulder, Colo.: Westview.

- Lieberson, Stanley 1994 ‘‘Understanding Ascriptive Stratification: Some Issues and Principles.’’ In David B. Grusky, ed., Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

- Lipset, Seymour M. 1959 Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Marx, Karl (1939) 1971 The Grundrisse. New York: Harper & Row.

- Marx, Karl (1894) 1972 Capital, 3 vols. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Mayer, Kurt B., and Walter Buckley 1970 Class and Society. New York: Random House.

- Meyer, John W. 1994 ‘‘The Evolution of Modern Stratification Systems.’’ In David B. Grusky, ed., Social Stratification: Class, Race, and Gender in Sociological Perspective. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

- Mosca, Gaetano 1939 The Ruling Class. New York: Mc-Graw-Hill.

- O’Leary, Brendan 1989 The Asiatic Mode of Production. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

- Pahl, R. E. 1989 ‘‘Is the Emperor Naked? Some Questions on the Adequacy of Sociological Theory in Urban and Regional Research.’’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 13:709–720.

- Parkin, Frank 1979 Marxism and Class Theory: A Bourgeois Critique. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Parsons, Talcott 1951 The Social System. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

- Parsons, Talcott 1954 Essays in Sociological Theory. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

- Poulantzas, Nicos 1974 Classes in Contemporary Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Ransford, H. Edward, and Jon Miller 1983 ‘‘Race, Sex, and Feminist Outlooks.’’ American Sociological Review 48:46–59.

- Rizzi, Bruno 1985 The Bureaucratization of the World. London: Tavistock.

- Roemer, John 1988 Free to Lose. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Sewell, William H., Archibald O. Haller, and Alejandro Portes 1969 ‘‘The Educational and Early Occupational Attainment Process.’’ American Sociological Review 34:82–92.

- Shaw, William H. 1978 Marx’s Theory of History. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

- Sørensen, Aage B. 1996 ‘‘The Structural Basis of Social Inequality.’’ American Journal of Sociology 101:1333–1365.

- Svalastoga, Kaare 1965 Social Differentiation. New York: D. McKay.

- Tawney, R. H. 1931 Equality. London: George Allen and Unwin.

- Tilly, Charles 1998 Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Treiman, Donald J. 1977 Occupational Prestige in Comparative Perspective. New York: Academic Press.

- Warner, W. Lloyd. 1949 Social Class in America. Chicago: Science Research Associates.

- Weber, Max (1922) 1968 Economy and Society. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Weber, Max 1946 From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, ed. and transl. by Hans Gerth and C. Wright Mills. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wesolowski, Wlodzimierz 1962 ‘‘Some Notes on the Functional Theory of Stratification.’’ Polish Sociological Bulletin 3–4:28–38.

- Wright, Erik O. 1978 Class, Crisis, and the State. London: New Left Books.

- Wright, Erik O. 1979 Class Structure and Income Determination. New York: Academic Press.

- Wright, Erik O. 1985 Classes. London: Verso.

- Wright, Erik O. 1989 The Debate on Classes. London: Verso.

- Wright, Erik O. 1997 Class Counts: Comparative Studies in Class Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wrong, Dennis H. 1959 ‘‘The Functional Theory of Stratification: Some Neglected Considerations.’’ American Sociological Review 24:772–782.

Browse other Sociology Research Paper Topics.