View the list of school psychology research paper topics. Read about the history of school psychology. Check other research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

School Psychology Research Paper Topics

Assessment

- Academic Achievement

- Adaptive Behavior Assessment

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Authentic Assessment

- Behavioral Assessment

- Bias (Testing)

- Buros Mental Measurements Yearbook

- Career Assessment

- Classroom Observation

- Criterion-Referenced Assessment

- Curriculum-Based Assessment

- Fluid Intelligence

- Functional Behavioral Assessment

- Infant Assessment

- Intelligence

- Interviewing

- Mental Age

- Motor Assessment

- Neuropsychological Assessment

- Outcomes-Based Assessment

- Performance-Based Assessment

- Personality Assessment

- Portfolio Assessment

- Preschool Assessment

- Projective Testing

- Psychometric g

- Reports (Psychological)

- Responsiveness to Intervention Model

- Social–Emotional Assessment

- Sociometric Assessment

- Written Language Assessment

Behavior

- Behavior

- Behavioral Concepts and Applications

- Behavioral Momentum

- Conditioning: Classical and Operant

- Generalization

- Keystone Behaviors

- Schedule of Reinforcement

Consultation

- Consultation: Behavioral

- Consultation: Conjoint Behavioral

- Consultation: Ecobehavioral

- Consultation: Mental Health

- Cross-Cultural Consultation

Development

- Developmental Milestones

- Egocentrism

- Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

- Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

- Perseveration

- Preschoolers

- Puberty

- Sensorimotor Stage of Development

- Theories of Human Development

Disorders

- Adjustment Disorder

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Bipolar Disorder (Childhood Onset)

- Communication Disorders

- Conduct Disorder

- Depression

- DSM-IV

- Dyslexia

- Echolalia

- Fears

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Learning Disabilities

- Mental Retardation

- Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Pedophilia

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- Psychopathology in Children

- Reactive Attachment Disorder of Infancy and Early Childhood

- Selective Mutism

- Separation Anxiety Disorder

- Somatoform Disorders

- Stuttering

Ethical/Legal Issues in School Psychology

- Confidentiality

- Ethical Issues in School Psychology

- Informed Consent

- Supervision in School Psychology

Family and Parenting

- Divorce Adjustment

- Parent Education and Parent Training

- Parenting

- Parents as Teachers

- Single-Parent Families

Interventions

Academic Interventions:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

- Classwide Peer Tutoring

- Cooperative Learning

- Mathematics Interventions and

- Strategies

- Peer Tutoring

- Reading Interventions and Strategies

- School–Home Notes

- Spelling Interventions and Strategies

- Study Skills

- Time on Task

- Tutoring

- Writing Interventions and Strategies

Behavioral Interventions:

- Behavior Contracting

- Behavior Intervention

- Biofeedback

- Corporal Punishment

- Positive Behavior Support

- Premack Principle

- Self-Management

- Task Analysis

- Time-Out

- Token Economy

- Verbal Praise

General Terms:

- Early Intervention

- Intervention

- Mathematics Curriculum and Instruction

Other Interventions:

- Cognitive–Behavioral Modification

- Crisis Intervention

- Evidence-Based Interventions

- Facilitated Communication

- Family Counseling

- Hypnosis

- Mentoring

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotropic Medications

- Student Improvement Teams

Social Interventions:

- Peer Mediation

- Social Skills

Issues Students Face

- Abuse and Neglect

- Death and Bereavement

- Homelessness

- Latchkey Children

Learning and Motivation

- Attention

- Cognitive Dissonance

- Generalization

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning

- Learning Styles

- Mastery Learning

- Memory

- Motivation

- Problem Solving

- Self-Concept and Efficacy

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Legislation

- Americans with Disabilities Act

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Act

- Individuals With Disabilities Education Act Disability Categories–Part B

- Section 504

Medical conditions

- Asthma

- Cancer

- Cerebral Palsy

- Eating Disorders

- Encopresis

- Enuresis

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- Fragile X Syndrome

- HIV/AIDS

- Lead Exposure

- Obesity in Children

- Otitis Media

- Phenylketonuria

- Pica

- Prader-Willi Syndrome

- Seizure Disorders

- Tourette’s Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury

Multicultural Issues

- Cross-Cultural Assessment

- Cross-Cultural Consultation

- Multicultural Education

Peers

- Friendships

- Peer Mediation

- Peer Pressure

Prevention

- DARE Program

- Positive Behavior Support

- Prevention

- Resilience and Protective Factors

Research

- Evidence-Based Interventions

- Qualitative Research

- Research

- Single-Case Experimental Design

School Actions

- Discipline

- Expulsion

- Retention and Promotion

- Suspension

School Psychologist Roles

- Careers in School Psychology

- Consultation: Behavioral

- Consultation: Conjoint Behavioral

- Consultation: Ecobehavioral

- Consultation: Mental Health

- Counseling

- Diagnosis and Labeling

- Home–School Collaboration

- Multidisciplinary Teams

- Parent Education and Parent Training

- Program Evaluation

- Reports (Psychological)

- Research

- Responsiveness to Intervention Model

- School Reform

School Psychology Organizations

- American Board of Professional Psychology

- American Psychological Association

- Council of Directors of School Psychology Programs

- Division of School Psychology (Division 16)

- International School Psychology Association

- Licensing and Certification in School Psychology

- National Association of School Psychologists

School-Related Terms

- Ability Grouping

- Class Size

- Classroom Climate

- Grades

- Homework

- No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, The

- Parent-Teacher Conferences

- School Climate

- Statewide Tests

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- S. Department of Education

- Zero Tolerance

School Types

- Charter Schools

- Full-Service Schools

- Head Start

- High School

- Homeschooling

- Middle School

- Montessori Schools

Special Education

- Accommodation

- Due Process

- Gifted Students

- Individualized Education Plan

- Individualized Education Plan Meeting

- Least Restrictive Environment

- Mainstreaming

- Manifestation Determination

- Multidisciplinary Teams

- Resource Rooms

- Special Education

Statistical and Measurement Terms

- Confidence Interval

- Effect Size

- Formative Evaluation

- Goal Attainment Scaling

- Grade Equivalent Scores

- Halo Effect

- Norm-Referenced Tests

- Normal Distribution

- Percentile Ranks

- Reliability

- Standard Deviation

- Standard Error of Measurement

- Standard Score

- Stanines

- Summative Evaluation

- Validity

Student Problematic Behavior

- Aggression in Schools

- Bullying and Victimization

- Cheating

- Dropouts

- Gangs

- Harassment

- School Refusal

- Self-Injurious Behavior

- Shyness

- Smoking (Teenage)

- Substance Abuse

- Suicide

- Teen Pregnancy

- Violence in Schools

History of School Psychology

The school psychology profession that exists today was shaped over the last century by multiple factors that continue to influence current thought and practice. These foundational influences are discussed in the initial section of this research paper and are followedbyareviewofthecurrentstatusofschoolpsychology in terms of roles and services, legal requirements, employment conditions, credentialing, infrastructure (professional associations, standards, journals), demographics, and supply-demand issues. The concluding section addresses probable future developments in light of current trends.

Although much has changed over the last century in psychology and education, the core features of school psychology practice have remained remarkably stable. School psychology’s earliest practitioners were concerned with identification and interventions for students with atypical patterns of learning and development, a core mission that dominates practice today. The principal basis for initiating services was then—and continues to be—referral of children due to learning problems, behavior problems, or both, most often by classroom teachers who are frustrated because the usual classroom strategies are not working. Moreover, then as now the vast majority of school psychologists’ professional practice involved a close association with educational services to students with disabilities such as mental retardation (MR), emotional disturbance (ED) and, recently, specific learning disability (SLD).

Throughout school psychology’s history there has been a parallel concern with enhancing the educational and developmental opportunities of all children through the implementation of sound mental health practices in schools, homes, neighborhoods, and communities. Current programs to establish schools as full-service educational and health agencies are one of the contemporary reflections of the latter trend. The broader positive mental health mission has always been, however, secondary to the core role of identification and interventions with students with learning and behavior problems.

Historical Trends

The early roots, the disciplinary foundations, and the societal trends that produced modern school psychology are discussed in this section. The early roots of school psychology emerged in the late 1890s in urban settings where school attendance was increasingly expected of all children and youth. Concerns for children with low achievement soon emerged, and efforts to identify the causes and solutions to low achievement were undertaken in several urban centers at about the same time (Fagan, 1992). It is interesting to note that the same concerns dominate most of school psychology practice today.

Disciplinary Foundations of School Psychology

Multiple disciplinary foundations exist for graduate education and school psychology practice. School psychology originated in the very early practice of what became clinical psychology involving the application of psychological methods to the understanding of learning and behavior problems of school-age children and youth (Fagan, 2000). Understanding and intervening with these problems always has involved multiple disciplines, including educational psychology (especially, the learning, measurement, and child development components), psychopathology and psychology of exceptional individuals, developmental psychology, counseling, clinical psychology, applied behavior analysis, and special education. These disciplinary foundations are clearly present in the authoritative statements of the crucial features of school psychology graduate education and practice (National Association of School Psychologists, 2000; Ysseldyke et al., 1997).

Societal Trends and School Psychology

School psychology always has been responsive to societal trends. In fact, whatever the current major issue is, it will be represented prominently in contemporary exhortations regarding what school psychologists should be doing. Two examples of this pattern should suffice. During the 1980s enormous emphasis was placed on drug abuse among youth and the school’s role in preventing drug abuse. The outcome was that awareness was increased and a few really good preventive programs were developed; however, although drug abuse continues to be a huge problem, relatively little attention is paid to this problem in the current school psychology literature.

A contemporary trend involves prevention of violence in schools, undoubtedly prompted by a few highly publicized horrific incidents in American schools resulting in the loss of approximately 60 students’ lives. The emphasis on violence prevention is important but perhaps a bit disproportionate in comparison to other more common problems. For example, overall, schools are overall, safer in the early 2000s than in the 1980s in terms of the number of lives lost in schools due to violence; however, youth violence remains a serious and often-discussed issue (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001).

The persistence and impact of school psychology’s attention to immediate societal problems depends on how well interventions become embedded in typical practice and implemented successfully in schools. For example, the use of group counseling and other peer group support procedures was expanded in the 1980s and then embedded in the practice of many school psychologists working in secondary schools. These methods are now applied to many different problems, including decision making about sexual behavior, social skills training, and, of course, drug abuse.

Similarly, the current emphasis on violence prevention will have a lasting influence in school psychology to the degree that the intervention methods developed are generally useful in preventing or ameliorating a range of problems. For example, the schoolwide interventions currently being implemented in schools as part of violence prevention efforts have positive influences on overall school and classroom climate, on preventing violent incidents, and on the reduction of other problems such as disciplinary referrals and dropout rates (Horner & Sugai, 2000; Sugai et al., 2000; Walker et al., 1996). If these interventions are incorporated into standard practice, then the current attention to school violence will have a lasting and positive effect.

Compulsory Education and Educational Outcomes

Fagan (1992) documented the impact of compulsory schooling on the development of school psychology in the twentieth century. Compulsory schooling and (increasingly) the expectation of high educational achievement for all children and youth continue to influence school psychology. Exceptional patterns of development and differences in achievement became much more problematic with compulsory school attendance beginning in the early 1900s and expanding through the rest of the century. A contemporary expression of the expansion of compulsory schooling is the strong emphasis on improving school attendance and preventing school withdrawal prior to the completion of high school. School dropout after a certain age (age 14, 15, or 16) was tolerated more readily in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Today, dropout prevention is a major goal of school reform along with expectations for high achievement for all children and youth (McDonnell, McLaughlin, & Morison, 1997).

Compulsory school attendance and expectations for high achievement for all students influenced early and contemporary school psychology in many ways. More children were in public schools. Moreover, through the century it was progressively less likely that students with serious achievement and behavior problems were excluded from schools, increasing the need for school psychological services and educational accommodations for students who varied on important dimensions related to education (learning rate, cognitive functioning, behavior, etc.). Today the demand for high achievement for all students, including those with disabilities, places more emphasis on effective general and special education interventions and school psychology services that are directly related to producing better outcomes.

Exceptional Individuals and Special Education

School psychology always emphasized recognition of individual differences in learning and development. The association with special education also occurred early in the history of school psychology, and (as discussed later) the existence of school psychology has closely paralleled the development of special education funding in the states. In most states, school psychologists have had mandated roles with the development of special education eligibility and placement. Part of that role always has been measurement of individual differences, often through comparing individual performance to national normative standards, and the development of educational programs to accommodate those differences.

Child Study and Mental Health

The early child study movement in the 1890 to 1910 period was another foundation for school psychology (Fagan, 1992). Child study methods later merged with school and clinical psychology and formed the basis for the increasingly close ties of school psychology to special education. The mental health movement that emerged in the 1920s is the basis for contemporary efforts to prevent academic, social-behavioral, and emotional problems through positive parenting and responsive school programs. The mental health movement has fostered many different approaches to prevention and intervention, varying from the psychoanalytic and psychodynamic roots in the early period to contemporary, behaviorally based schoolwide positive discipline programs. The effectiveness of mental health programs always has been controversial (e.g., Bickman, 1997).

Individual Rights and Legal Guarantees

The expansion of individual rights and legal guarantees to educational services for all children and youth exerted vast influences on school psychology. The U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that outlawed segregation of students by race in public schools initiated a movement that continues to grow and develop. Brown and subsequent litigation and legislation established strong sanctions against differential treatment of individuals on the basis of race, sex, age, and disability status (Reschly & Bersoff, 1999). Perhaps the most pervasive effect of this movement was to change the relationship of parents and students to schools. The discretion of schools to limit access or to segregate students was changed forever. Moreover, parents and students increasingly acquired the rights to challenge the decisions of educators and to seek redress in the courts.

The greatest current influences on school psychology are the court cases and legislation guaranteeing educational rights to students with disabilities (SWD). As noted later, the expanded rights changed the practice of school psychology in significant ways and markedly expanded special education and school psychology.

Demographics and Current Practice Conditions

The current status of school psychology is discussed in this section, including roles and practices, employment conditions, personnel needs, and demographics. The characteristics of school psychology practice and practitioners have changed rapidly in a few areas while many other factors have remained stable over the last quarter century.

Employment

Numbers and Salaries

The number of school psychologists working in public school positions in the United States is impossible to know with certainty. Two methods have been used to estimate the total employed in schools—surveys of state department of education personnel and state school psychology leadership officials and the annual state reports to the Federal Office for Special Education Programs (OSEP) of personnel employed working with SWD. The results of the two methods are generally very similar in overall numbers and correlated at r .9 or above (Lund, Reschly, & Martin, 1998). The OSEP results may be a very slight undercount because they do not include practitioners in schools not counted as working with special education programs.

According to the most recent OSEP count, over 25,000 school psychologists are employed in school settings. There are perhaps another 3,000 school psychology practitioners working in other roles in schools, such as director of special education, or in other settings, such as medical clinics, community mental health, and private practice. Other career settings for school psychologists include college and university teaching and research as well as state department of education staff. Of course, some persons with graduate education and experience in school psychology are in a very wide variety of roles such as university president, college provost and dean, school superintendent or principal, test publishing, and private consultation. The exact number of persons with school psychology graduate education and experience in the schools working in related careers or settings is impossible to determine; however, it is likely that the there are at least 30,000 such persons.

School psychology employment has grown rapidly since the enactment of the Education of the Handicapped Act (EHA; 1975, 1977), now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; 1991, 1997, 1999). Prior to about 1975, the number of school psychologists and the ratio of students to psychologists in a state depended very heavily on whether the state had strong special education legislation and—as a part of that legislation—funding for school psychological services. Kicklighter (1976) reported an average ratio of about 22,000 students to one psychologist and a median of about 9,000 students per psychologist. The large differences between the median and mean indicate that there were enormous differences between states and regions and generally high (by present standards; see later discussion) ratios in nearly all localities (Fagan, 1988).

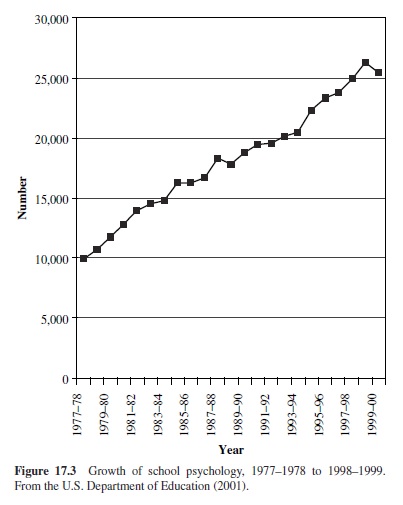

School psychology’s growth over the last 25 years is documented through OSEP annual reports on the implementation of EHA and IDEA since 1976 (see Figure 17.3 later in this research paper; U.S. Department of Education, 1978–2001). The number of school psychologists over that time period increased from about 10,000 in 1977–1978 to more than 26,000 in 1998–1999—an increase of more than 150%. Approximately 750 school psychologists have been added annually to the profession, severely challenging the ability of graduate programs to provide an adequate supply of fully credentialed persons (see later discussion). For example, in the most recent year for which data are available, 1998–1999 (U.S. Department of Education, 2001), 1,025 of the 26,266 psychologists reported by the states to OSEP were not fully certified as school psychologists. Moreover, the growth of school psychology is tied to school budgets. Increased growth has occurred in good economic times (Lund et al., 1998), and it is likely that less growth or perhaps even a slight contraction is currently underway. Figure 17.3 (later in this research paper) summarizes the growth of school psychology by year since 1977–1978.

Employers and Salary

The vast majority of school psychologists (85% or more) work for publicly supported educational agencies such as school districts or regional education units. Most practitioners work very closely with special education programs in which they have particularly demanding responsibilities with disability diagnosis and special education program placement (see later discussion of roles and legal influences). Most are employed on 190- to 200-day contracts. The salaries for school psychologists nearly always are determined by years of professional experience, degree level, length of contract, and—occasionally—increased by supervisory responsibilities, specialized roles, or unique strengths such as bilingual capabilities. The average beginning salary is in the low $30,000s, but the variations among districts, states, and regions are substantial. The average salary for a school psychologist with a 190-day contract, 15 years of experience, and the equivalent of specialist-level graduate education (see later section) is in the mid-$50,000s, although again, there are large regional variations (Hosp & Reschly, 2002).

Job Satisfaction

Overall, the job satisfaction of school psychologists has been positive and stable over the last two decades. Reschly and colleagues began studies of job satisfaction in the mid-1980s in response to anecdotal reports that many school psychologists were unhappy with their work and planned to leave the profession in the near future (Vensel, 1981). Contrary to the anecdotal observations that received a good deal of attention in the early 1980s, job satisfaction is generally positive. The vast majority of practitioners plan to continue in school psychology for many years or until retirement and are satisfied with their career choice (Hosp & Reschly, 2002; Reschly, Genshaft, & Binder, 1987; Reschly & Wilson, 1995).

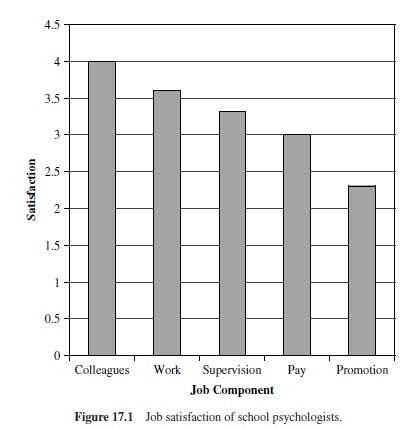

The picture becomes more nuanced when different aspects of job satisfaction are considered. Using a five-area job satisfaction scale in a Likert scale format patterned after the fivefactor content of the Job Descriptive Index (JDI; Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969), Reschly and Wilson’s (1995) national survey results indicated high and positive satisfaction with colleagues and work, moderate satisfaction with supervision, and neutral perceptions of pay, but they also reported low satisfaction with promotion opportunities—a pattern also reported by Hosp and Reschly (2002) in a more recent survey (see Figure 17.1). For many practitioners—especially those at the specialist level of graduate preparation— advancement opportunities are seen as rather limited. One of the advantages associated with doctoral-level graduate education for practitioners is greater opportunity to pursue alternative career settings or to augment the usual role with other professional activities such as teaching in a local college, private practice, or consulting. Persons engaged in these activities generally see the job advancement and promotion opportunities more positively.

Demographics

Gender

School psychology demographics have changed significantly over the last 40 years (Reschly, 2000). The greatest changes occurred in gender; the practitioner work force has changed from 40% to 70% female. This gender trend is likely to continue because today slightly more than 80% of all school psychology graduate students are women. The composition of school psychology faculty, which started at a lower proportion of women (20%) also reflects the same trend; about 50% of all faculty are female currently. The gender trends in school psychology are consistent with the increasing feminization of psychology generally—a strong trend that is apparent among undergraduate majors and graduate students in all areas of psychology (Pion et al., 1996). The proportion of women in graduate programs in many areas of psychology— including clinical and counseling—are close to the 80% figure cited previously for school psychology.

Age

The average age of school psychology practitioners has increased from about 38–47 since 1985 (Curtis, Hunley, Walker, & Baker, 1999; Hosp & Reschly, 2002; Reschly et al., 1987). Similar age trends likely exist with school psychology faculty who were about 6 years older than practitioners in a 1992 survey (Reschly & Wilson, 1995). The advancing age of practitioners and faculty creates opportunities for greater gender representation among faculty, a trend that appears to be well underway and (perhaps) increasing diversity among all types of school psychologists. Moreover, the likely high rate of retirements over the next decade will contribute to the already healthy demand for school psychologists in both practitioner and faculty positions.

Diversity

Greater diversity in school psychology is an intense need and challenge. Curtis et al. (1999) reported that approximately 5.5% of practitioners identified themselves as being in a nonCaucasian group; however, only 1% reported being African American and 1.7% were self-identified as Hispanic. Graduate program enrollments and faculty have become slightly more diverse over the last decade; minority faculty membership has increased from 11% to 15%, and minority graduate students have increased from 13% to 17% (McMaster, Reschly, & Peters, 1989; Thomas, 1998). The latter statistics on minority representation were not reported by group; hence, there is no way to determine whether the most underrepresented groups (African American and Hispanic) are increasing.Regardlessofthislastpoint,thecompositionoftheschool psychology profession is markedly different from the current U.S. public school population, which is approximately 1% AmericanIndian,4%AsianorPacificIslander,15%Hispanic, 17% African American, and 63% White. It is likely that the racial-ethnic compositions of school psychologists and students will continue to be very different far into the future.

Degree Level

One of the most controversial issues is the appropriate level of graduate education for the independent, nonsupervised practice of school psychology in schools and other settings. Degree level is the principal issue that divides the American Psychological Association (APA) and its Division 16 (School Psychology) from the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP; see this research paper’s later section on infrastructure). The degree composition of the current practitioner force is heavily at the specialist level—that is, 60 hours of graduate work in an organized program of study in school psychology with a 1-year internship. Although surveys differ slightly, about 75% of the current practitioners are at the specialist level and about 25% are at the doctoral level. Over the past 25 years there has been an enormous shift from the masters to the specialist level, and over the same period, the proportion of doctoral-level practitioners has only slightly increased. The current pattern is highly likely to continue because the vast majority of current school psychology graduate students are in specialist-level programs (75–80%), and the majority of school psychology graduate programs are located in institutions that are not authorized by their governing authorities to offer doctoral degrees in any area (Reschly & Wilson, 1997; Thomas, 1998).

The data on degree level of current practitioners and graduate students destroy the credibility of assertions in the mid1980s that school psychology was rapidly changing to the doctoral level (Brown, 1987, 1989a, 1989b; Brown & Minke, 1986). Brown predicted that “. . . by 1990 over half of the students in training will be at the doctoral level” and that “. . . a majority of graduates in the near future will be doctoral” (1987, p. 755). Others suggested a slightly less rapid progression toward the doctoral level—for example, Fagan predicted that half of all practitioners in 2010 would be doctoral (Fagan, 1986). Past and current trends make those predictions impossible to achieve. In fact, school psychology is a largely nondoctoral profession and is likely to remain so for several decades into the new century.

Roles and Services

Based on the traditional literature (Cutts, 1955; Fagan & Wise, 2000; Magary, 1967; Phye & Reschly, 1979; White & Harris, 1961), the following summary reflects the research of Reschly and colleagues on the roles of school psychologists (Reschly & Wilson, 1995, p. 69).

- Psychoeducational assessment is “evaluations for diagnosis of handicapping conditions, testing, scoring and interpretation, report writing, eligibility or placement conferences with teachers and parents, re-evaluations.”

- Interventions refer to “direct work with students, teachers, and parents to improve competencies or to solve problems, counseling, social skills groups, parent or teacher training, crisis intervention.”

- Problem-solving consultation refers to “working with consultees (teachers or parents) with students as clients, problem identification, problem analysis, treatment design and implementation, and treatment evaluation.”

- Systems-organizational consultation refers to “working toward system level changes, improved organizational functioning, school policy, prevention of problems, general curriculum issues.”

- Research-evaluation refers to “program evaluation, grant writing, needs assessment, determining correlates of performance, evaluating effects of programs.”

Using this scheme, several surveys (Hosp & Reschly, 2002; Reschly et al., 1987; Reschly & Wilson, 1995) have yielded generally consistent results regarding practitioners’ perceptions of their current and preferred roles (see Figure 17.2). The current services of school psychologists involve a heavy emphasis on psychoeducational assessment, which accounts for over half of the role (Hosp & Reschly, 2002). Approximately 35% of the time is devoted to direct interventions and problemsolving consultation, with less than 10% devoted to systemsorganizational consultation and research-evaluation. Preferred roles involve significantly less time in assessment (32%) and slightly more time in each of the other four roles.

Further information on the character of school psychology services is revealed by responses to the following item: How much of your time is spent in determining special education eligibility, staffings, follow-up on placements, and reevaluations? The average amount of time in services strongly connected to special education eligibility, and placement in 1997 was 60%. Moreover, the results of a survey on the use of different assessment instruments or approaches further supported the strong tie to eligibility determination in special education. School psychology assessment is dominated by assessment of intellectual ability and the use of other measures related to determining eligibility for special education such as behavior rating scales and projective assessment devices. The behavior rating scales are nearly always completed by teachers or parents and the projective devices used typically were the less complex variety, such as figure drawings and sentence completion tasks. A good case can be made that IQ testing for the purpose of determining special education eligibility still dominates much of school psychology practice.

Ratios and Regional Differences

The content thus far on demographics, roles, and services has been based on averages derived from national surveys of school psychologists that mask large variations between regions, states, and districts within states. Regional differences are a significant influence on the interpretation of some of these results. A good example of the large variations among regions is the ratio of students to psychologists. The national ratio is about 1900:1. That overall average masks significant regional variations that differ from 3800:1 in the EastSouth-Central states to 1000:1 in the New England states (Hosp & Reschly, 2002). Even greater variations exist among states and in some cases between districts within the same state. It is therefore difficult to generalize about school psychology practice across all districts, states, and regions. The variables discussed thus far that are most affected by regional factors are—in addition to ratio—salary (higher in the eastern and western coasts and lower in the southern and WestSouth-Central states), assessment practices (more IQ testing in the southern states and less in the Northeast; less use of projective measures in the central and mountain states), and nonassessment roles (more time devoted to them in the East and less in the Pacific states). Job satisfaction, age, gender composition, and time devoted to special education services did not vary substantially across the regions.

Legal Requirements

Legal requirements influence every facet of school psychology practice in schools and in many other settings. Public schools are creations of federal, state, and local governments. School psychology employment depends heavily on public funding—a generally secure foundation that expands or contracts at a moderate rates with economic circumstances. Varied sources of legal requirements and legal mechanisms influence the practice of school psychology (Prasse, 2002; Reschly & Bersoff, 1999).

The sources of legal requirements influencing school psychology vary from the U.S. Constitution’s 5th and 14th Amendments used in the Diana (1970), Guadalupe (1972)— both cases regarding minority overrepresentation in special education—and Pennsylvania Association of Retarded Children v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (1972)—a landmark right of students with mental retardation to appropriate educational services, due process protections, and participation in normal educational environments to the greatest extent feasible—to regulations developed by state education agencies. Litigation beginning in the late 1960s continues to markedly influence school psychology practice (Reschly & Bersoff, 1999). Although litigation and constitutional protections continue to be important, the greatest contemporary legal influences come from federal statutes and regulations and state statutes and rules governing the provision of educational services to students with disabilities (Reschly, 2000).

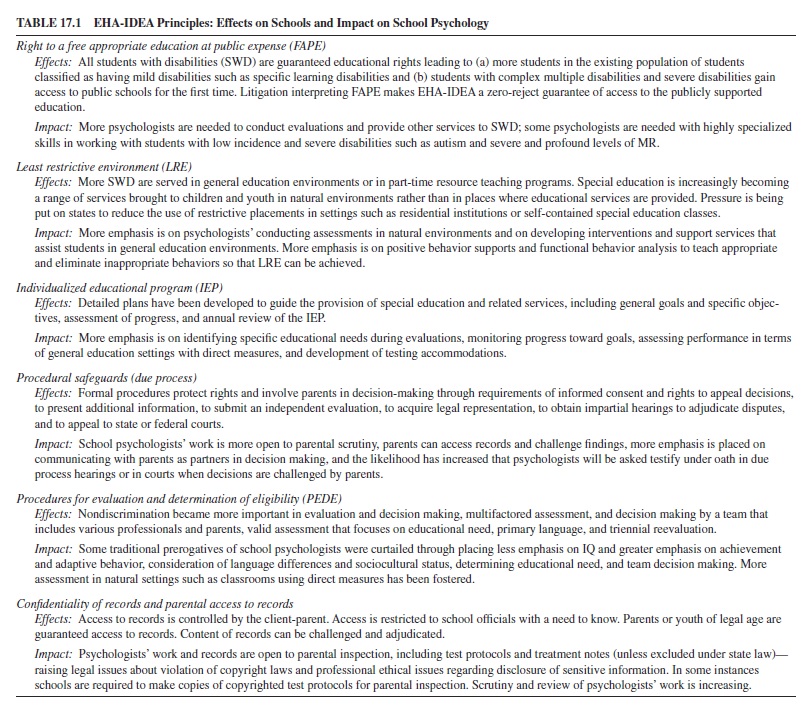

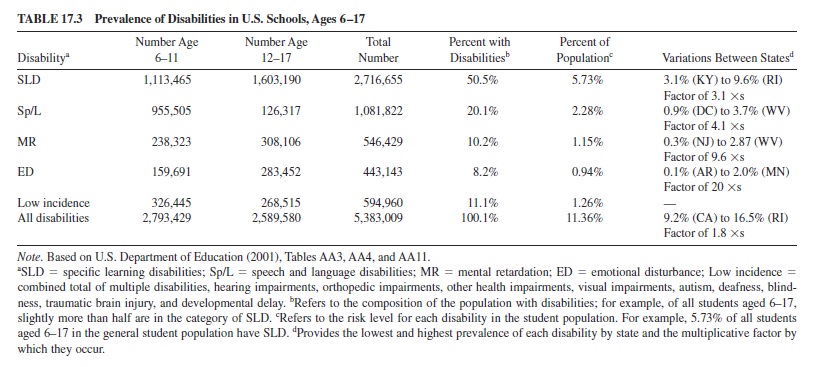

Legislation

The previously cited litigation was instrumental in the development of state and federal legislation regarding the educational rights of children and youth with disabilities. The EHA (1975, 1977) was the touchstone federal legislation that appears in an updated form today as IDEA (1991, 1997, 1999). All of the major principles of IDEA—that is, free appropriate education at public expense, least restrictive environment, individualized educational programs, procedural safeguards, and nondiscrimination and appropriate assessment—appeared earlier in the EHA. These principles and their implications for school psychology practice are summarized in Table 17.1. For example, the state and federal guarantees of a free and appropriate education for all SWD greatly increased the number of such students in the public school setting (from about 2.2 million students age 6–17 to over 5 million today), markedly increasing the number of eligibility evaluations and reevaluations.

Psychological services are defined in the IDEA regulations, but the terms school psychology or school psychologist do not appear in the IDEA statute or regulations. A broad conception of psychological services appears in the following IDEA (1999) regulations:

(9) Psychological services includes—

-

Administering psychological and educational tests, and other assessment procedures;

-

Interpreting assessment results;

-

Obtaining, integrating, and interpreting informationabout child behavior and conditions relating to learning;

-

Consulting with other staff members in planning schoolprograms to meet the special needs of children as indicated by psychological tests, interviews, and behavioral evaluations;

-

Planning and managing a program of psychological services, including psychological counseling for children and parents; and

-

Assisting in developing positive behavioral interventionstrategies.

Although the conception of psychological services in the IDEA regulations is broad and progressive, the actual effects of the close association with special education constitute a two-edged sword for school psychology. One side is that the legislation has prompted the enormous growth in school psychology over the last 25 years and provides a secure funding base in nearly all states. Strong special education funding nearly always has meant strong funding for school psychology, and vice versa. The other side is that the top service priority for the vast majority of school psychologists is to conduct eligibility evaluations and to participate in other special education placement activities, thus limiting the amount of time available for preventive mental health, direct interventions, and problem-solving consultation.

Assessment and Eligibility Determination Regulations

In addition to greater demand, the nature of school psychological services changed dramatically after 1975 and continues to change with statutes and regulations that require eligibility evaluations to meet certain standards. The regulations that have the most influence on school psychology practice appear as the Procedures for Evaluation and Determination of Eligibility section of the federal IDEAregulations (34 C. F. R. 300530 through 543). Comparable state education agency rules exist at the state level. The key regulations that have the most impact on school psychology practice are:

- A full and individual evaluation that meets certain standards must be conducted prior to determining eligibility for disability status and placement in special education.

- The evaluation must not be racially or culturally discriminatory, and it must be administered in the child’s native language unless to do so is clearly not feasible.

- Disability classification shall not occur if the tests or other evaluation procedures are unduly affected by language differences.

- The evaluation results must be relevant to determining disability eligibility and to the development of the child’s individualized educational program.

- Standardized tests must be validated for the purpose for which they are used and must be administered by knowledgeable and trained personnel in accordance with test publishers’ requirements.

- Tests and other evaluation procedures must focus on specific educational needs, not merely on a single construct such as general intellectual functioning.

- The evaluation accounts for the effects of other limitations such as sensory loss or psychomotor disabilities and does not merely reflect those limitations.

- No single procedure is used; a multifactored assessment must be provided that includes areas related to the suspected disability, including (if appropriate) health, vision, hearing, social and emotional status, general intelligence, academic performance, communicative status, and motor abilities. All of the child’s special education and related services needs must be identified regardless of whether those needs are commonly associated with a specific disability.

- A review of existing information pertaining to the child’s disability eligibility and special education program placement must be conducted every 3 years or more often if requested by a parent or teacher. A comprehensive reevaluation may be conducted as part of the review.

- An evaluation report shared with parents must be developed.

- Eligibility and placement decisions must be based on a wide variety of information and be made by a team that includes evaluation personnel, teachers, special educators, and parents.

- In the area of SLD, a severe discrepancy must be established between achievement and intellectual ability; furthermore, cause of the SLD cannot be sensory impairment; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; or environmental, economic, or cultural disadvantage.

The discerning reader will notice almost immediately the inherent ambiguity in many regulations. For example, what does nondiscrimination or validated for a specific purpose mean? Does nondiscrimination mean equal average scores for all groups on relevant measures? Equal predictive accuracy? Equal classification and placement outcomes? Similarly, how valid is sufficiently valid to meet the legal requirement? Is a validity coefficient of r .5 sufficient, or does it have to be higher? No answers are given in the regulations, and for the most part, these questions have not been answered in litigation. Some of the regulations regarding eligibility evaluation might be regarded best as aspirational because—given the current state of knowledge—achieving nondiscrimination in an absolute sense or attaining perfect or near-perfect validity are nearly impossible. Clearly, the regulations give notice that high-quality evaluations are required and that special sensitivity to sociocultural differences is expected.

In addition to the regulations governing the processes and procedures for eligibility evaluations, the actual disability classification criteria also exert a strong influence on the kinds of evaluations conducted by school psychologists. The IDEA regulations provide conceptual definitions for 13 disabilities. The federal conceptual definitions generally indicate the fundamental bases for each of the disability categories—for example, MR is defined in terms of intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior, but classification criteria are not provided in the federal regulations (e.g., the IQ and adaptive behavior cutoff scores to define eligibility in MR). The state education agency rules generally are the most important influences on classification criteria.

States have wide discretion in the use of disability categories and disability names and—most especially—in the classification criteria used to define disabilities. The frequent use of standardized tests of intellectual functioning and achievement by school psychologists is closely tied to the nature of these state eligibility criteria. The disability with the highest prevalence, SLD (accounting for over half of all SWD), is operationalized by classification criteria that require a severe discrepancy between intellectual ability and achievement. The exact criterion or criteria for the discrepancy varies by state with some establishing relatively less (e.g., 1 SD) and some relatively more (1.5 or 2.0 SD) stringent standards. The use of an IQ test, however, is nearly always required to implement the SLD classification criteria—a practice that may be changing. Likewise, in MR an IQ test nearly always is required by states to determine the child’s status on the intellectual functioning dimension of the MR disability category.

IQ testing often is done routinely as part of a comprehensive evaluation for other suspected disabilities such as emotional disturbance or autism, although the classification criteria for these disabilities rarely mention intellectual functioning specifically. For many school and child psychologists, an IQ test is an essential part of an overall evaluation (Sattler, 2001). This view appears to be changing as more emphasis is placed on accountability for child outcomes in special education legislation and practice (see this research paper’s section on future trends).

Trends in Legal Requirements

The EHA-IDEA legal requirements and their state counterparts have evolved gradually over the last 25 years, with changes primarily in the realm of further specification of requirements or inclusion of broader age ranges in the mandate to serve SWD. IDEA (1991, 1997, 1999) represented a modest break with the prior trends; the greater emphasis was on accountability for academic and social outcomes for SWD and the use of regulatory powers to focus greater attention on positive outcomes. Prior to 1997, IDEA-EHA legal requirements focused on process, inclusion, and extending services to all eligible children and youth. Compliance monitoring prior to 1997 involved checking on whether the mandated services were provided without cost to parents in the least restrictive environment feasible and were guided by an individualized educational program and an evaluation that included essential features; procedural safeguards followed rigorously. The missing element in this array of legal requirements was outcomes—that is, what tangible benefits were derived by children and youth from participating in special education and related services programs?

The greater emphasis on outcomes in special education legal requirements follows the national trends in the late 1980s and 1990s toward greater accountability through systematic assessment of student achievement (McDonnell et al., 1997). Several additions were made by Congress to the IDEA regulations (1991, 1997, 1999) to ensure greater accountability in special education. Among these requirements are the strong preference for SWD to remain in the general education curriculum, to participate in local and state assessment programs (including the standardized achievement testing that is done at least annually in nearly all states), and to have individualized educational programs that are developed around general education curriculum standards.

The effects of this legislation on SWD are not clear yet, but the accountability demands influence school psychology in a number of ways. First, evaluations must include content from the general education classroom and curriculum in order to provide the information needed for planning the special education program. More emphasis on curriculum-based measurement is highly likely (Shapiro, 1996; Shinn, 1998) along with other direct measures of classroom performance. Second, the portions of reevaluations involving progress in achieving goals must in most cases include a general education context as well as the results of the child’s performance in the school’s accountability program. These areas are becoming essential components of annual reviews of progress and triennial reevaluations of disability eligibility and special education program placement. Third, school psychologists are involved frequently in judgments about the alterations in standardized testing procedures that are needed in order for SWD to participate, without undermining the essential purpose of the assessment. Finally—and most important—the work of school psychologists is increasingly examined in relation to outcomes for children, leading to scrutiny of the value of standardized tests and other assessment procedures in facilitating positive outcomes for SWD (discussed later in this research paper; Reschly & Tilly, 1999).

IDEA (1991, 1997, 1999) also placed more emphasis on the delivery of effective interventions for social and emotional behaviors that might interfere with academic performance or that lead to placement in more restrictive education settings for SWD. A positive behavior support plan is required in every IEP if social or emotional behavior interferes with learning—a frequent occurrence for SWD. Moreover, before disciplinary action can be taken against SWD, a functional behavior analysis must be conducted with interventions implemented (Tilly, Knoster, & Ikeda, 2000), a requirement that focuses more attention on outcomes and draws heavily on the expertise that some school psychologists have with applied behavior analysis.

Summary of Legal Requirements

It is this author’s thesis that legal requirements are the greatest influence on the existence and work of school psychologists. The close association of school psychology with special education emerged in the early twentieth century, developed rapidly over the last 25 years, and continues to evolve. The legal requirements themselves are, of course, the outgrowth of societal trends that placed great value on the rights of each individual—including persons with disabilities—to educational services. Further changes in legal requirements should be expected with concomitant further influences on school psychology.

School Psychology Infrastructure

The infrastructure for school psychology includes the body of knowledge claimed by the profession, graduate programs, standards, professional associations, and credentialing mechanisms (including licensing and state education agency certification). The school psychology infrastructure grew rapidly over the last 25 years in parallel with the legal requirements necessitating the employment of school psychologists and the rapid increase in the numbers of school psychologists.

Professional Associations

School psychology professional associations exist in the United States, Canada, most nations of the European Community, and selected other nations throughout the world. There is an International Association of School Psychologists that holds an annual summer seminar, usually in Europe or North America. In addition, all states have school psychology associations, as do most Canadian provinces. The two major national school psychology organizations in the United States are discussed in this research paper. Readers interested in the international association are encouraged to consult their Web site (http://www.ispaweb.org/en/index.html).

Division 16 of the APA

The oldest national school psychology organization in the United States is Division 16 (School Psychology) of the APA (http://education.indiana.edu/~div16/). Division 16 was founded in the late 1940s when the APA was reorganized and the divisional structure was established. Many of the other divisions such as Educational Psychology (Division 15) and Clinical Psychology (Division 12) were established at the same time. Full membership in the APA requires a doctoral degree, rendering ineligible for full membership the vast majority of practicing school psychologists who have specialist-levelgraduate education. For that and perhaps other reasons the membership of Division 16 is a relatively small percentage of the overall school psychology community, dominated principally by university faculty. The membership of Division 16 is composed of 174 fellows, 1,392 members, and 226 associates (associates generally are graduate students or nondoctoral affiliates of theAPA).

Division 16 plays a vital role in representing school psychology in the broader realm of American psychology and professional psychology. Division 16 is very powerful when it can align its interests with those of the much larger APA (over 84,000 members). Major activities of this Division are publishing a journal (School Psychology Quarterly) and a newsletter (The School Psychologist), the developing of standards documents, advocating for school psychology services, and maintaining school psychology as one of the four officially recognized areas of professional psychology in APA (along with clinical, counseling, and industrial-organizational). Division 16 organizes a program at the annual APA conventions that includes awards to outstanding members, symposia, invited addresses, and poster sessions.

National Association of School Psychologists

The NASP (http://www.nasponline.org/index2.html) was established in 1969 to represent the interests of all school psychologists, with special attention to the interests and needs of most practitioners who were at that time primarily at the master’s level of graduate preparation. The NASP admitted all persons certified or licensed to practice in a state as a school psychologist as well as graduate students in school psychology to full membership. Today NASP is the largest school psychology organization in the world with approximately 22,000 members, of whom about 5,000 have doctoral-level graduate preparation. Although it might have been accurate to characterize Division 16 and NASPin the 1970s and 1980s as representing the interests of doctoral- and nondoctorallevel school psychologists, respectively, it now is clear that about four times as many school psychologists with doctoral degrees are in NASP as in APA. NASP maintains a headquarters in the Washington, DC area and has an executive director and a growing staff that conducts the organization’s business, provides membership services, and advocates for school psychological services.

NASP publishes a journal (The School Psychology Review), a newsletter (NASP Communique), and a variety of monographs such as Best Practices (now in a fourth edition), a graduate training directory, and reports of innovative practices in such areas as intervention techniques and models (Shinn, Walker, & Stoner, 2002). NASP also publishes graduate program standards and provides a program approval service through an affiliation with the National Council on Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE). NASP program approval is especially influential at the specialist level, whereas APA accreditation dominates at the doctoral level. A national credential with increasing recognition by the states was established by NASP in the early 1990s, the National Certificate in School Psychology (NCSP). Close relationships are maintained with nearly all of the state associations of school psychologists through a variety of cooperative and serviceoriented programs. Over the past decade, NASP has become increasingly active and influential in shaping federal policies that affect school psychologists—especially the IDEA(1991, 1997, 1999) legislation.

The principal disagreement between APA Division 16 and NASP is the appropriate entry level for the independent, unsupervised practice of school psychology in public and private settings. NASP advocates the specialist level, and Division 16—in line with APA policy—promotes the doctoral level. The dispute over entry level has been intense and divisive at different times in the history of school psychology (Bardon, 1979; Brown, 1979; Coulter, 1989; Hyman, 1979; Trachtman, 1981), although (with a few exceptions) it has not been a prominent issue at the national level for the two organizations in recent years. Intense struggles over this issue sometimes still occur at the state level drawing in the national leadership, but these events have been rare in the 1990s.

The outcome of the debate over entry level is relatively clear in most states. The entry level for practice in the schools is the specialist level, whereas the entry level for the private, independent practice of school psychology generally is the doctoral level. When school psychologists at the specialist level do attain the authority to practice privately without supervision by a doctoral-level professional, that practice typically is limited to a narrow range of services.

Increased cooperation on the many common interests that exist between NASP and APAhas been the prevailing pattern during the 1990s, although the official policies of the organizations continue to differ sharply on the graduate preparation required to use the title school psychologist. For reasons discussed in the next section, it is highly unlikely that school psychology practitioners will reach the doctoral level for several decades into the future. The APA and NASP cooperation is in the best interests of both organizations and consistent with both organizations’ commitment to expanding and improving psychological services for children and youth (Fagan, 1986a).

Graduate Programs

Graduate programs in school psychology have been studied with increasing intensity over the last 35 years (Bardon, Costanza, & Walker, 1971; Bardon & Walker, 1972; Bardon & Wenger, 1974, 1976; Bluestein, 1967; Brown & Lindstrom, 1977; Brown & Minke, 1984, 1986; Cardon & French, 1968–1969; Fagan, 1985, 1986b; French & McCloskey, 1979, 1980; Goh, 1977; McMaster et al., 1989; Pfeiffer & Marmo, 1981; Reschly & McMaster-Beyer, 1991; Reschly & Wilson, 1997; Smith & Fagan, 1995; Thomas, 1998; White, 1963–1964). The early studies were restricted to a listing of the available programs with meager analyses of the characteristics or the nature of the programs. Beginning with the NASP-sponsored graduate programs directories led by Brown and colleagues (Brown & Lindstrom, 1977; Brown & Minke, 1984) and then continued by others (McMaster et al., 1989; Thomas, 1998), a more complete picture of school psychology graduate education has emerged.

Two levels of graduate education are prominent in school psychology. The specialist level typically involves 2 years of full-time study in an organized school psychology program, the accumulation of 60 semester hours at the graduate level in approved courses, and a full-time internship during a third year, usually with remuneration at about a half-time rate for a beginning school psychologist. Specialist-level programs typically are designed around NASP standards for graduate programs in school psychology (NASP, 2000). Most specialist-program students complete their programs in 3 years. The overwhelming majority of specialist-program graduates are employed in public school settings as school psychologists.

Doctoral programs involve at least 3 years of full-time study on campus, followed by a full-time internship that usually is paid but at a level well below beginning salaries for psychologists, and a year for dissertation completion. Students occasionally complete doctoral degrees in 4 years, but 5–6 years is much more common in school psychology programs. Doctoral requirements typically follow APA accreditation standards (APA, 1996). Career paths of doctoral program graduates are highly variable. Many work in nonschool settings such as medical clinics or community mental health, whereas others go into teaching and research roles in universities. Perhaps 40% of doctoral graduates work in public school settings as school psychologists or as program administrators.

The specialist level dominates school psychology graduate education and practice, and it is likely to continue to do so. Specialist-level graduate students constitute about 70% of all graduate students and 80% of all graduates of programs. The latter is, of course, the most accurate predictor of the future composition of the school psychology workforce. For many reasons that are well known to students and faculty, doctoral programs require a longer period of study (5–6 years) compared to specialist programs (3 years), not to mention the all-too-common occurrence of doctoral degree candidates’ delaying or failing to complete the degree because of the dissertation. For these and other reasons, there always will be a higher proportion of doctoral students than program graduates.

The number of institutions actively engaged in school psychology graduate education has remained stable for a decade, at about 195. Surveys sometimes list as many as 210–220 institutions, but closer examination indicates that about 195 institutions have active programs that admit and graduate students each year. Approximately 90% of the institutions offer specialist-level degrees; however, only 40% offer doctoral degrees (Thomas, 1998; Reschly & Wilson, 1997). A limitation in the movement to the doctoral level is that about 60% of the institutions that offer school psychology graduate programs are not authorized by their governing boards or state legislatures to offer doctoral degrees (Reschly & Wilson, 1997). The Carnegie Foundation classifies most of these institutions as comprehensive institutions, meaning that they offer undergraduate degree programs in a wide variety of areas and master’s or specialist degrees in selected areas. They are not authorized to offer doctoral degrees, and—in the current higher education climate—it is highly unlikely that very many of them will acquire the authority to offer doctoral degrees in the future.

In a development that most professional psychologists did not anticipate, master’s-level practice of counseling and clinical psychology has strengthened over the last decade due at least in part to the influences of managed care and other factors. The strong pressure that existed from APA Division 16 in the 1970s and 1980s appears to have diminished as a result of the dominance of managed care in the private-practice market and other developments (Benedict & Phelps, 1998; Phelps, Eisman, & Kohout, 1998).

The actual graduate education of specialist- and doctorallevel school psychologists overlaps significantly—especially in terms of preparation for practice in the school setting (Reschly & Wilson, 1997). Doctoral training is different primarily in (a) domains of supervised practice in nonschool settings; (b) specialization with a particular population, kind of problem, or treatment approach; and (c) advanced preparation in measurement, statistics, research design, and evaluation. These findings suggest that doctoral-level graduates are better prepared for broader practice roles, including evaluation of treatment and program effects and provision of services in nonschool settings. It is crucial to presenting an accurate picture to emphasize a high degree of overlap between specialist and doctoral graduate education as well as the large amount of variation across specialist programs and doctoral programs.

The only development on the horizon that might lead to a change in the largely specialist-level character of school psychology practice is the recent emergence of school psychology PsyD programs at the freestanding schools of professional psychology (SPP). There are approximately 25 SPPs in the United States today that have been devoted almost exclusively to training clinical psychologists. The SPPs are noted for being expensive, for offering little student financial aid other than loans, and for graduating large numbers of students compared to more traditional university-based programs. Today these 25 schools of professional psychology graduate twice as many clinical psychologists as do the approximately 185 university-based clinical programs (How Do Professional Schools’ Graduates Compare with Traditional Graduates?, 1997; Maher, 1999; Yu et al., 1997). Clearly the SPPs have shown the capacity to train and graduate large numbers of persons. Due to changes in managed care as well as the rapid increase in the numbers of clinical psychologists—especially those from the SPPs—the market demand for doctoral-level clinical and counseling psychologists has diminished, as have the number of applications for admission to clinical and counseling graduate programs.

The SPPs are tuition driven—that is, they depend directly and primarily on student-paid tuition and fees to support the institution. They also are entrepreneurial. The weakening demand for clinical psychologists has led some of the SPPs to enter new areas of training. One of the California SPPs has initiated a teacher education program, and the SPPs in Fresno, CA and Chicago have announced plans to initiate PsyD programs in school psychology. Clearly, these announcements represent entrepreneurial efforts to maintain financial viability rather than a long-standing commitment to these new areas. If the other SPPs enter school psychology training and graduate large numbers of persons, the current supply-demand picture and the dominance of the specialist level could change over the next decade.

I am very skeptical about the SPPs’ role in school psychology training as well as their attractiveness to prospective school psychologists. An SPP graduate education is enormously expensive in view of realistic expectations for postgraduate salary levels; moreover, the typical SPP graduate acquires enormous debt. Recent conversations with training directors at several of the SPPs suggest that the average graduate school debt of 1999 graduates was in the $80,000–$100,000 range. I doubt that very many students will choose SPPs in view of the current average beginning school psychology salaries of $30,000 to $40,000.

Graduate Program Standards and Accreditation-Approval

APA and NASP provide graduate program standards and program accreditation or approval services (Fagan & Wells, 2000). The NASP standards are preeminent for specialistlevel programs, whereas the APA standards clearly dominate at the doctoral level. The NASP Standards for Training and Field Placement Programs in School Psychology (hereafter NASP Standards) first appeared in 1972, and the most recent revision was published in 2000. Copies are available at http://www.nasponline.org/index2.html. The NASP Standards are applicable to both doctoral and specialist programs; however, the main influence is at the specialist level. The specialist-level standards require a minimum of 60 semester hours, 2 years of full-time study in an organized program, coverage of essential content, a supervised practicum, and a full-year supervised internship in the 3rd year. The domains of graduate training in the NASP Standards, based on the Blueprint (Ysseldyke et al., 1997), are data-based decision making and accountability, consultation and collaboration, effective instruction and development of cognitive-academic skills, socialization and development of life skills, student diversity in development and learning, school and system organization, policy development, and climate, prevention, crisis intervention, and mental health, home-school-community collaboration, research and program evaluation, school psychology practice and development, and information technology.

Standards also are published for practicum experiences during the on-campus part of the program and forthe full-time internship (NASP, 2000). NASP Standards are implemented through a folio review process involving submission of an extensive array of documents (course syllabi, practicum and internship contracts, etc.). There is no on-site component of the program approval process, weakening the evaluation of a program’s implementation of the standards. NASP publishes a list of approved programs biannually in the NASP Communique. According to the NASP Web site cited previously, 125 institutions are approved at the specialist level of graduate education in school psychology. Overall, the NASP Standards and the program approval process have stimulated improved graduate education at the specialist level—leading to more faculty in programs, more coherent training, and improved supervised experiences. The NASP approval process could be strengthened with an on-campus site visit component.

The APA Guidelines and Principles for Accreditation of Programs in Professional Psychology (hereafter APA Standards; APA, 1996; http://www.apa.org/) are the most recent iteration of APA program accreditation services that can be traced to 1945. APA accredits doctoral-level programs only, in three of the four areas of professional psychology— clinical, counseling, and school. The fourth area of professional psychology, industrial-organizational, has never sought program accreditation. Recent APA policies permit the expansion of accreditation to new areas of professional psychology (e.g., developmental psychology), but so far no institutions with programs in the nontraditional areas have been accredited. Unlike the NASP Standards, the APA Standards are generic in the sense that they are designed to apply to all areas of professional psychology—not a single area such as school psychology.

The APA Standards require the institution to specify a training model and then organize experiences that produce the outcomes consistent with that model. Despite the appearance of a system that allows maximum freedom in the design of graduate education, the APA Standards specify essential domains in which “all students can acquire and demonstrate understanding of and competence . . .” The domains listed are biological bases of behavior, cognitive and affective aspects of behavior, social aspects of behavior, history and systems of psychology, psychological measurement, research methodology, techniques of data analysis, individual differences in behavior, human development, dysfunctional behavior or psychopathology, professional standards and ethics, theories and methods of assessment and diagnosis, effective interventions, consultation and supervision, evaluation of the efficacy of interventions, cultural and individual diversity, and attitudes essential to lifelong learning and problem solving as psychologists. Obvious overlap exists in the NASPand APA Standards; however, the NASP Standards are more specific to the training of school psychologists, whereas the APA Standards are more generic and pertain to the graduate education across areas of professional psychology.

APA has accredited graduate programs in school psychology since 1971 (Fagan & Wells, 2000). Currently there are 66 institutions with accredited programs in school psychology or school psychology and another area (combined accreditation in either school and clinical or school and counseling). The institutional location of about 80% of the APA-accredited school psychology programs is a college of education, often a department of educational psychology or a department of counseling and school psychology. The college and department profile of counseling and school psychology is almost identical. In contrast, APA-accredited clinical programs are usually located in departments of psychology in arts and sciences colleges (about 80%; Reschly & Wilson, 1997) or in freestanding SPPs. A significant proportion of the graduate education in professional psychology occurs in colleges of education, usually within a broader context of educational psychology or a context that is significantly influenced by educational psychology.

APA accreditation processes involve a self-study, submission of documents to APA, and a site visit by a three-person team over a 2- to 3-day period. The site visit is rigorous, and most programs seeking initial accreditation receive either conditional accreditation or are rejected. Most apply again and eventually gain full accreditation. It is extremely rare for a program that is fully accredited to lose its accreditation, although a few programs have managed to do so.

Summary

Clearly, APA accreditation is the oldest and most prestigious of the mechanisms whereby a school psychology graduate program is endorsed by an authoritative body. APAaccreditation is, however, available only to doctoral programs that account for less than half of all school psychology graduate programs. The recent development of the NASP approval process is a significant milestone in improving specialistlevel graduate education. It is highly likely that dual accreditation-approval mechanisms in school psychology will be needed far into the future unless an unlikely breakthrough occurs in the current APA and NASP disagreement on the appropriate level of graduate education required for independent school psychology practice.

School Psychology Scholarship

Improvements in school psychology scholarship are apparent in a number of developments over the last three decades. Over that period a significant number of books and monographs have been devoted to school psychology thought and practice. The Bibliography: for some of the most prominent contemporary resources are Fagan and Wise (2000); Reschly, Tilly, and Grimes (1999); Reynolds and Gutkin (1999); Shinn et al. (2002); and Thomas and Grimes (2002). NASP publishes monographs relevant to school psychology and cooperates with other publishers in marketing books and other materials that are relevant to school psychology. Some of the books developed by APA publications also are relevant to school psychology (e.g., Phelps, 1998).

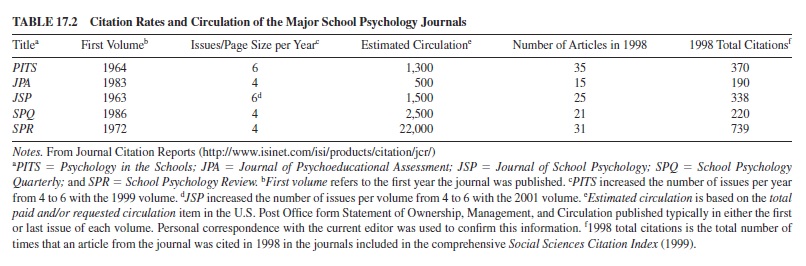

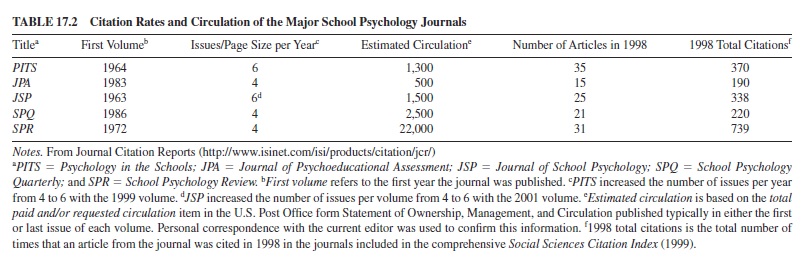

The major U.S. refereed journals in school psychology that publish content directly or closely related to school practice are School Psychology Review (SPR), Journal of School Psychology, Psychology in the Schools, Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, and School Psychology Quarterly. Information on these journals appears in Table 17.2. SPR, published by NASP, is the leading journal in the discipline based on its circulation (approximately 22,000) and on the number of citations to articles published in the journal—that is, the number of times a particular article is cited by other scholars. The other school psychology journals have much lower circulation ( 2,500) and lower citation rates. It is important to note, however, that valuable content is published by each of the school psychology journals, and conscientious scholars need to examine the contents of each.

The Federal Department of Education, especially the Office of Special Education Programs, is the major source of funding for school psychology research and personnel preparation. Other important sources of support are the Federal Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Innovation, the National Institute of Health (particularly the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development), and private foundations. Research awards are provided by the Society for the Study of School Psychology (SSSPS), Division 16 of APA, and NASP. SSSPS provides approximately $65,000–$90,000 in small grants to school psychology investigators annually.

School psychology has grown at a rapid pace over the last three decades (see Figure 17.3). The rapid growth was tied directly to the expansion of special education legal mandates. These mandates have the most influence on the existence of school psychologists and the services they provide, and it is highly likely that the legal influences will be crucial to school psychology in the future. There are, however, a number of problems in this relationship and with contemporary practice that likely will prompt significant changes in school psychology practice in the future.

Disability Determination and Special Education Placement

As noted previously, the practice of school psychology today is closely tied to special education eligibility determination and placement. The tie to special education is supported by special education legal requirements, the federal and state requirements for the legally mandated full and individual evaluation, and current conceptual definitions and classification criteria for educationally related disabilities. The disabilities that consume the most time for school psychologists are SLD, MR, and ED. Changes in the conceptual definitions or classification criteria for any of these disabilities—especially for SLD due to the large numbers in that category—could have a significant impact on school psychology. It is likely that such changes will occur.

What happens to school psychology if the intellectual functioning requirement is removed from the SLD classification criteria? What if states and the federal government adopt noncategorical conceptions of high-incidence disabilities (SLD, MR, ED) with disability classification based on low achievement and insufficient response to high-quality interventions, as recommended by a recent National Academy of Sciences Report (Donovan & Cross, 2002)?