View sample Nontraditional Psychological Treatments Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The term ‘psychotherapy’ generally connotes an interactive, face-to-face process in which a trained mental health professional attempts to help a client or group of clients effect personal change. Authority and responsibility for facilitating such change reside with the professional, whose presence and expertise are deemed necessary to guide and control the meetings in accordance with sound clinical and ethical practices.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Since the 1970s an array of interventions for delivering psychological assistance have come into being that deviate significantly from the traditional psychotherapy format. In general these newer formats enjoy widespread popularity among the general public and their use is less directly controlled by a mental health professional. Such alternative psychological interventions include self-help and mutual support groups, radio and TV shows dispensing psychological advice, interactive computer software packages for addressing a wide variety of personal problems, self-help books, self-help audio and video tapes, and most recently a spate of cyberspace offerings. The latter category includes self-help guides, single session e-mail and bulletin board advice, ongoing e-mail counseling, real-time chat groups, and most recently, web telephony and videoconferencing.

A small body of research evaluating effectiveness focuses primarily on paraprofessionals and self-help books, and shows these alternatives to be sometimes as effective as more classic psychotherapy. However, much more research is needed. Added benefits of alternative formats are lower cost, convenience of access and use, and the availability of psychological aid for people who otherwise either would not, or could not, utilize traditional psychotherapy. Examples include the homebound, those in remote areas, people who consider psychotherapy stigmatizing, and individuals with a strong need for privacy and independence when dealing with their psychological problems.

This research paper first examines some of the social and cultural factors contributing to the development and use of these newer forms of psychological treatment. The treatments themselves are then reviewed along two dimensions. The first dimension is the source of the help: is it professional, paraprofessional, nonprofessional, or some mix? The second dimension is the nature and degree of contact between help giver and help seeker. Finally, the status of research, along with issues about quality, safety, and protection of the public are briefly discussed.

1. Social Climate And The Rise Of New Forms Of Psychological Treatment

Viewed as a group, the newer models of psychological assistance, as compared with traditional forms of psychotherapy, tend to involve less direct professional contact and control, even when the treatment is designed or delivered by a mental health professional. This shift away from strictly professional delivery of mental health services reflects an intersection of several social developments. Observations about social trends are based on developments in the USA and may differ in applicability to other parts of the world.

At a broad societal level, considerable value has come to be placed on empowering the individual, as opposed to almost total reliance on institutions and professionals for information, support, and assistance. This stems in part from a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam weakening of US public confidence in its major institutions, including the corporate world, government, and the medical establishment. Various activist movements (e.g., those concerning civil rights, women, consumer rights, gays and lesbians), beginning in the 1960s and continuing to the present, also reinforce values about personal entitlement and empowerment. A result of this trend is that people now demand a greater measure of involvement and control over their physical and mental health care.

Technological advances in communications are a further factor in stimulating individual desire for greater control of over personal well-being. Before the 1980s many personal issues such as alcohol and drug abuse, child molestation, family violence, sexual orientation, bulimia and anorexia nervosa, cancer, sexually transmitted diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, fetal alcohol syndrome, mental illness, to name but a few, were topics rarely spoken of in public. Early television talk shows played an important role in shining a spotlight on such previously closeted issues. As people became increasingly sophisticated about the relationship between stress and health, and the potential damage that various stressful life events can cause, the public also demonstrated its eagerness for help.

However, scientific surveys of the prevalence and incidence of mental health problems, at least insofar as the US public is concerned, make it clear that we do not now have, and probably never will have, a sufficient number of trained mental health professionals to meet the needs of all those reporting diagnosable psychological problems. Meanwhile, the need for psychological services continues to grow, fed in part by dramatic advances in medical science. More people with serious chronic medical conditions are surviving, many into old age, putting numerous stresses on both patients and their families.

At the same time, the growth of managed health care, with its focus on cost containment, has resulted in limiting access to care, especially for mental health concerns. This is so despite a growing body of research from the field of psychoneuroimmunology (Hafen et al. 1996), demonstrating that psychological stressors have a negative impact on the immune system, general health, and overall functioning. The same body of research also shows the social support and the opportunity to discuss problems constructively can positively affect health, enhance the quality of life, and even promote longevity. Western medicine, though desirous of promoting health and preventing the occurrence or the worsening of disease, fails fully to capitalize on what is known about the mind–body connection and its impact on health and well-being.

Further, under managed care, doctors and nurses, traditionally an important source of informal psychological assistance, now have less time to spend with their patients than in the past. The ironic result is a public increasingly aware of the connection between stress and physical and psychological illness, but finding affordable psychological services growing more scarce.

To summarize, four factors stand out as particularly influential in promoting nontraditional psychological treatments: (a) the growing public awareness and desire for help at the very time that for many the availability of affordable professional psychotherapy is decreasing; (b) the value placed on personal entitlement and empowerment in today’s society; (c) an ongoing revolution in electronic forms of communication, including the very rapid growth and easy accessibility of information and services via the Internet; (d) the rapid dissemination of information by today’s highly competitive mass media businesses. Given these forces, it is not surprising that enterprising people have, and no doubt will continue to find, alternative, accessible, less costly (although sometimes financially quite profitable) ways of delivering psychological treatments.

One such example of a break from traditional psychotherapy began in the late 1970s, as the number and type of self-help mutual support groups multiplied rapidly (Goodman and Jacobs 1994). Such groups had existed for decades, the best known being Alcoholics Anonymous and Recovery, Inc. But suddenly groups sprang up for almost every conceivable personal problem from substance abuse, to parenting concerns, to being a victim of violence, to life transitions such as divorce, retirement, or bereavement, to lifestyle issues such as sexual orientation, transvestitism, open marriages, as well as groups for almost every disease listed by the World Health Organization. Millions of people joined them and, although some groups utilize professional leaders or professionally developed ideas, many have little or no professional input. Sociologist Frank Reissman (Gartner and Reissman 1984) terms the heart of the self-help group movement the ‘helper therapy’ principle—the idea that when people suffering from a common problem come together for mutual support, they not only receive help from others, particularly from those more experienced in coping with the problem, but also give help, and in so doing are themselves strengthened and empowered. In the 1980s many health professionals held negative views about self-help groups, asserting that lay people left on their own were likely to harm each other by dispensing bad advice. Less openly discussed were their concerns over loss of professional control and income. Over time professionals have become more supportive of self-help groups as both an adjunct to traditional treatment and as a useful, membergoverned intervention in its own right. Today many professionals are directly involved with groups in a variety of roles such as consultants, researchers, leaders, co-leaders with group members, and even as participants who share the group’s common concern.

More recent alternatives to traditional psychotherapy have been generated as a result of the ongoing technological revolution in electronic communication, which continues to offer new means of interacting to large numbers of people. On the Internet, some formats take advantage of real-time communication to deliver psychological aid, while others necessitate time delays between the posting of messages requesting psychological help and the responses to those messages. One recent review of psychological assistance on the Internet (Barak 1999), listed 10 types of interventions: (a) information resources on psychological concepts and issues; (b) self-help guides; (c) psychological testing and assessment; (d) help in deciding to undergo therapy; (e) information about specific psychological services; (f ) single-session psychological advice through e-mail or e-bulletin boards; (g) ongoing personal counseling and therapy through e-mail; (h) real-time counseling through chat, web telephony, and videoconferencing; (i) real-time and delayed-time support groups, discussion groups, and group counseling; ( j) psychological and social research. The next section offers a framework for organizing the many and varied nontraditional intervention formats offered to the public.

2. A Framework For Viewing Nontraditional Forms Of Psychological Assistance

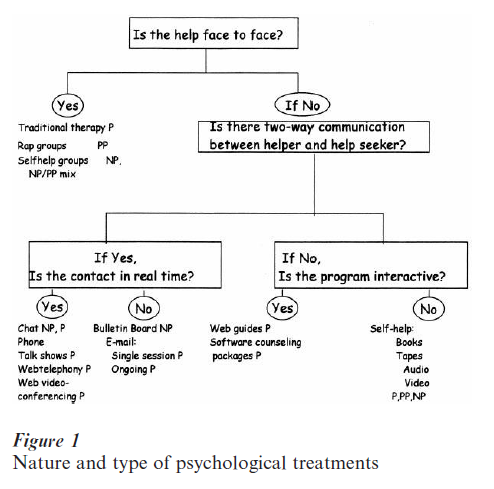

Two basic elements in most traditional psychotherapy are (a) live, real-time, face-to-face contact between a help seeker and a help giver and (b) the help giver being a trained mental health professional. This section outlines alternative psychological treatments in terms of their departure from these two elements, that is, alternative formats for delivering psychological aid are shown according to two major categorizations.

The first categorization is the nature of the contact between help seeker and the source of the help: is it live and face-to-face? If not, is there some type of two-way communication between the helper and help seeker? If so, is it in real time or delayed time? (Note that in either case, the true identity of either party may not be known.) If not, does the help seeker interact and receive feedback from a packaged program such as those that can be bought and used on personal computers or accessed via the Internet? If not, what is the format for the delivery of the noninteractive aid?

The second categorization refers to the training of the person offering the mental health aid: is the person a trained mental health professional, a paraprofessional, or a nonprofessional? The intention is to provide a framework for categorizing any type of psychological treatment. For the examples listed in Fig. 1, P = professional, PP = paraprofessional, and NP = nonprofessional. The listing is not intended to be exhaustive.

The relatively unregulated nature of the various forms of nontraditional psychological treatment being offered to the lay public has raised concerns about their safety, quality, and effectiveness. Research into the use of paraprofessionals vs. professionals, self-help books vs. therapist-delivered services, and computer-assisted vs. therapist-delivered treatment generally shows these alternatives to be similar in effective-ness to professionally delivered psychotherapy (Christensen and Jacobson 1994). But not only is that body of scientific studies relatively small, some newer computer-based formats have never been studied. Thus, many important questions remain unanswered. For example, are some nontraditional formats more appropriate for certain types of people, or certain types or levels of severity of problem?

Further, the relatively unregulated nature of the Internet leaves open the possibility of poor quality offerings, untested claims, and even outright charlatanism among those designing and offering psychological assistance. In the interest of assuring quality psychological services for the public, priority needs to be given to research, as well as education for both Internet users and service providers, about appropriate standards.

Bibliography:

- Barak A 1999 Psychological applications on the Internet: A discipline on the threshold of a new millennium. Applied and Preventative Psychology 8: 231–45

- Christensen A, Jacobson N S 1994 Who (or what) can do psychotherapy: The status and challenge of nonprofessional therapies. Psychological Science 5: 8–14

- Gartner A, Reissman F 1984 Self-help Revolution. Human Services Press, New York

- Goodman G Jacobs M K 1994 The self-help, mutual support group. In: Fuhriman A, Burlingame G M (eds.) Handbook of Group Psychotherapy. Wiley, New York, pp. 489–526

- Hafen B Q, Karren K J, Frandsen K J, Smith N L 1996 Mind Body Health The Effects of Attitudes, Emotions and Relationships. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA