View sample situational approaches to terrorism research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The situational approach to terrorism evolved from situational crime prevention, a well-established evidence-based approach to preventing and reducing crime. It argues that terrorists make choices that are limited by their perception of the opportunities afforded to them to carry out their mission. The situational approach explains how terrorists carry out their missions in contrast to why they do so. There are four pillars of terrorist opportunity: targets, weapons, availability of tools for doing attacks, and local conditions that facilitate terrorist operations. By manipulating these opportunities, interventions are directed at increasing the effort of mounting an attack, increasing the risk of carrying out an attack, reducing the rewards of attacks, reducing provocations to terrorists, and removing excuses terrorists use to justify their attacks. Because the situational approach focuses primarily on prevention, it places great emphasis on planning, which makes it a natural supplement to disaster response planning and to problem-oriented policing that seeks to solve crime and disorder problems. It is thus particularly useful to local police as a guide for developing local counterterrorism strategies.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Introduction

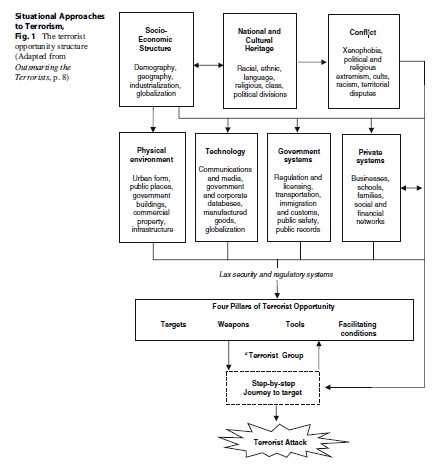

Situational approaches to terrorism derive from several decades of research, theory, and practice in the field of situational crime prevention. Pioneered by Ronald V. Clarke in 1988 in his seminal paper on coal gas suicides, situational crime prevention has evolved in many respects outside of mainstream criminology, which, since its inception in the nineteenth century, has been preoccupied with the root causes of crime, the search for the “born” or “made” criminal. Dominated by political science, the approach to terrorism has paralleled that of criminology: the search for the root causes of terrorism, with an overwhelming focus on its ideological, psychocultural, economic, and political causes. In contrast, the situational approach takes up where mainstream explanatory models leave off: it begins with a pinpoint focus on the specific situations in which terrorism occurs and, depending on the type of terrorism, works backwards to the causes. It does not completely eschew root causes; it views them as distant, background factors which for the most part are impermeable to counterterrorism interventions (see Fig. 1).

This conceptual distinction between situational crime prevention and other approaches in social science drives it to ask questions that others do not: how did the offender get to the point of being able to carry out his crime? What immediate factors in the social and physical environment produced a situation in which the crime was possible? Situational crime prevention asks not why but how an offender carries out his tasks. It is concerned with motives rather than motivation. It is concerned with intervention rather than causation. It takes seriously the old adage “prevention is better than cure.”

Situational crime prevention is often attacked by those who hold to a contrasting view: “You can’t cure an illness (disease, crime, terrorism) by treating its symptoms.” The symptoms may disappear, but then reappear in some other form because the root causes have not been diagnosed. Counterterrorist experts complain, “If we protect this government building, they’ll attack a shopping mall.” This seems like a devastating blow to the situational crime prevention approach, but it is not as will be seen later in this research paper. First, it is necessary to address the basic, intractable problem in the study of the causes and response to terrorism: its definition.

The Situational Definition Of Terrorism

The definition of terrorism is famously elusive. The United Nations has tried for many years to agree on a definition and failed. The problem is political, legal, and conceptual. The political difficulty is reflected in the popular saying, “one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” The conceptual problem is tied up with the legal (which essentially binds the conceptual to the political). For example, serious political disagreements arose in the United States when the Obama administration chose to define the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center as criminal acts and therefore subject to the regular due process of US criminal law. Opponents of that view argued that they were not criminal acts but acts of war against the USA, so that other legal procedures should follow. Others claimed that the attacks were not acts of war or criminal acts but something else – the position eventually favored by the Bush administration and resulted in setting up the prison in Guantanamo Bay, a kind of legal “nowhere land.”

The situational approach finds these debates as mostly irrelevant to its enterprise. In fact, as noted earlier, situational crime prevention began with a study of suicide, an act arguably not always a crime, depending on the jurisdiction and circumstances of its commission. As it evolved, situational crime prevention developed more and more a focus on the specificity of the crime which often cuts across the traditional definitions of crime. This had important ramifications in respect to how crime was measured and recorded. Simply recording and reporting the number of burglaries, for example, in a police jurisdiction, were found to be useless for research or for prevention. It was necessary to collect very specific information about very specific types of burglaries: single-family residences or apartment blocks? Suburban or urban neighborhoods? Commercial or business districts? Adjacent to parks or woods? and so on. Generally speaking, it is the definition of the situation that is important for both research and prevention purposes, rather than the definition of the crime. So for the purposes of situational crime prevention, it does not really matter what one calls it, a crime, terrorist attack, or even an accident; it is the analysis of the situation in which these events occur that is of prime importance. As a result, Clarke and Newman in their book Outsmarting the Terrorists sidestep the issue by defining terrorism simply as “crime with a political motive.”

The Situational Approach To Terrorism

Apart from the importance of specificity already discussed, there are three basic operating principles that play an important part in any analysis of terrorism from the situational perspective. These are opportunity, rational choice, and intervention.

- Opportunity. This principle simply states that in order for a terrorist attack to be accomplished, the environmental and social conditions must be such that they offer advantage to the terrorist for carrying out the attack. For example, before there were cars, car theft was not possible. Before there were computers, software piracy was not possible. It is true that “theft” and “piracy” in the generic sense have always been possible, but it is clear that to speak of preventing or even analyzing such crimes, it makes little sense without examining their specific attributes. Furthermore, the social and physical environment may be structured in such a way that easy access to the targets of crime or terrorism is available. For example, early computers or cars were never designed in anticipation of software piracy or car theft. The mosaic of factors that make various crimes or terrorist attacks possible is called the opportunity structure as shown in Fig. 1.

- Rational choice. Depending on what the terrorist wants to achieve by his attack (i.e., his motives), the terrorist will carry out his enterprise according to a rational choice from available options (i.e., part of the opportunity structure). The observer may consider what the terrorist is doing to be “irrational” such as the terrorist who kills himself in order to successfully complete an attack. This is called “limited” rationality as expounded by Cornish and Clarke in their groundbreaking work The Reasoning Criminal. Failure to understand the way terrorists think contributed to the shortsighted US counterterrorist policy which assumed that terrorists would not hijack an airplane and willingly kill themselves in the process – the unanticipated methodology of the 9/11 attacks.

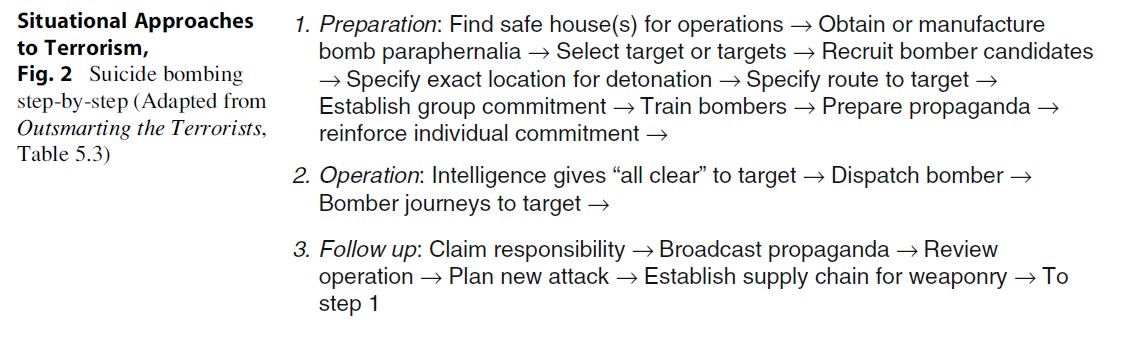

- Intervention. Situational crime prevention always begins from the point of how to disrupt the sequence of events that result from the offender’s decision making. This involves generally two procedures for revealing points of weakness in the offender’s or terrorist’s action sequence. First, a step-by-step analysis is conducted to find out exactly the sequence of choices made by the terrorist in his journey to the target. For example, in the case of a suicide bomber, we must follow his journey from induction into the pool of potential bombers, his training, the selection of the target, and finally his journey to the target (see Fig. 2).

The journey to crime has been studied for a wide range of crimes including burglary, car theft, sex offenses, and robbery. Recent work emphasizing the step-by-step approach has adopted the concept of “scripting” from cognitive psychology which examines in detail the decision-making process and techniques used by offenders to exploit opportunities and accomplish their task. This approach has been used in analyzing credit card and check fraud, suicide bombing, Internet child pornography, identity theft, and trafficking in endangered species. The second important aspect of intervention is to conduct a careful assessment of the opportunity structure to identify weak points of security that may be exploited by criminals or terrorists. For example, particular targets may be more vulnerable, exposed, or accessible than others. Once these have been identified, the appropriate security systems may be installed. This is an important feature of situational crime prevention because it implies that there is much that can be done to protect targets even without knowing who the terrorists are or what their motivation may be.

Guided by the three principles of opportunity, rational choice, and intervention, Professors Clarke and Newman have developed a comprehensive approach to explaining terrorism which also provides a structure for organizing responses to terrorism. This helps to connect the often disjointed study of terrorism that focuses either entirely on the terrorist’s characteristics or entirely on law enforcement responses to those characteristics. Instead, Clarke and Newman advocate that we “think terrorist” in order to identify a modus operandi according the opportunities available. The terrorist is placed within the opportunity structure of terrorism which is primarily composed of what they call the four pillars of terrorist opportunity: targets, weapons, tools, and facilitating conditions.

The Four Pillars Of Terrorist Opportunity

- Targets

In theory, terrorists could attack any target, as many politicians and law enforcement individuals have worried ever since 9/11. In practice, they must choose their targets carefully. And this choice will be strongly conditioned by the inherent attractiveness of those targets to terrorists, summarized as EVIL DONE:

Exposed: The Twin Towers were sitting ducks. Vital: Electricity grids, transportation systems, and communications are vital to all communities. Iconic: Of symbolic value to the enemy, for example, Statue of Liberty, the Pentagon, and the Twin Towers.

Legitimate: Terrorists’ sympathizers cheered when the Twin Towers collapsed.

Destructible: The Murrah building in Oklahoma City and Twin Towers on 9/11.

Occupied: Kill as many people as possible.

Near: Within reach of terrorist group and close to home base.

Easy: The Murrah building was an easy target to a car bomb placed within 8 feet of its perimeter. Of the above characteristics, the proximity of the target to the base of operations (near) is probably the most important. Research has noted that terrorists will base their operations in regions and countries where the local population is sympathetic to their cause. As noted earlier, the importance of proximity to target and base of operations has been known for some time in situational crime prevention research on the offender’s journey to the crime. The reason is that the closer to base of operations, the more detailed information can be collected concerning the accessibility of the target and the route to the intended attack. Street and traffic conditions, for example, may be significant in carrying out a suicide bombing. If a target is distant, it will be much more difficult to obtain the necessary operational information. This is why all Al-Qaeda attacks against the USA, except the attacks on the World Trade Center, have been conducted against US targets overseas (embassies and military bases). These targets were generally much closer to the bases of operations of Al-Qaeda. In the case of the Al-Qaeda attacks on the US World Trade Center in 1993 and 2001, it was necessary to set up satellite bases close to the targets. Subsequent successful and failed attempts in the UK and USA have revealed that attacks inspired by Al-Qaeda have been carried out by individuals who were born of immigrant parents within the home country, though in some cases received training from terrorist camps overseas. Thus, the traditional distinction between domestic and foreign terrorism no longer holds, but the necessity of proximity of the terrorist base of operations to the target remains supreme.

- Weapons

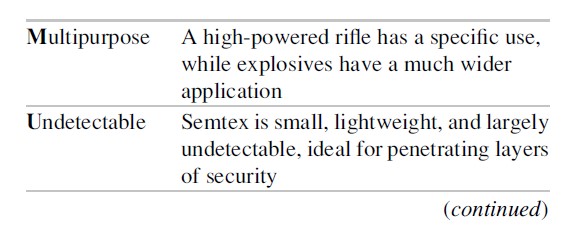

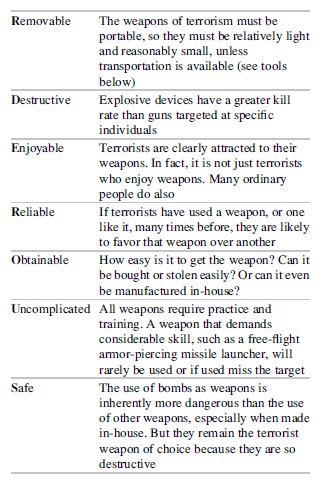

As with targets, terrorists favor certain weapons over others. The majority of terrorist attacks are conducted using small arms and munitions. Attacks with weapons of so-called mass destruction (biological or nuclear) have been few, and where conducted, of limited effect. The characteristics of weapons that make them appealing to terrorists are MURDEROUS:

There will almost always be a trade-off between the target of choice and the weapon. If a target is particularly desirable, or difficult to reach, there may be a search for an appropriate weapon. For example, the first attack on the US World Trade Center in 1993 used a truck bomb parked under one of the towers. Though it did much damage, it failed to destroy the target which at the time was considered indestructible. The second attack used a new weapon, a passenger jet as missile, which was successful. The planning required to use this new weapon was very extensive and took years to accomplish. It also required Al-Qaeda to locate a satellite base of operations in the USA close to the targets (the relevant airports and target itself). Finally, it ignored the one attractive characteristic of weapons listed above: it was not “safe.” The users, as with suicide bombers, were willing to die in order to reach the target. However, we should note that in the case of “regular suicide bombers,” the explosives used are well developed and “safe” for those managing the training of the suicide bombers. The explosive vest must be well constructed so that it is detonated only when the bomber reaches the target.

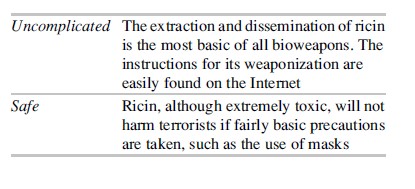

Weapons of mass destruction, including biological weapons, have been rarely used by terrorists. The reason is that such weapons generally do not fit the MURDEROUS requirements of weaponry to terrorists. However, using this approach, Hassan Naqvi reviewed the main biological and chemical weapons theoretically available to terrorists and concluded that ricin toxin would be the most attractive weapon because of its exceptionally MURDEROUS qualities:

- Tools

Terrorist attacks cannot be accomplished without the tools of everyday life. Without such tools, it is much harder for terrorists to reach a target or use their weapons. For many of the commonest attacks, such as car or truck bombings, drive-by shootings, and targeted assassinations, terrorists are likely to need most of the following:

- Cell phones or other means of communication

- Cars or trucks to transport themselves and weapons

- Cash or (false) credit cards, bank accounts, or other means of transferring money

- Documents (false or stolen) – for example, drivers’ licenses, passports or visas, and vehicle registration documents

- Maps (and increasingly GPS), building plans, and addresses so that the target location can be pinpointed

- Television sets and monitors

- Video and still cameras for surveillance

- Internet access to collect information on street closures, traffic patterns, weather conditions, local news, and disseminate propaganda worldwide

Depending on the availability of such tools, the weaponry employed and targets reached may vary.

It may seem obvious that terrorists would need these everyday tools, but it is not obvious how they can use them without divulging at some point who they are and what they are up to. These tools are certainly widely available, but their visibility is also considerable. Using cash instead of a credit card to rent a car, for example, draws unwanted attention to the terrorist. Using a credit card exposes one’s identity – unless it is stolen. For these reasons, terrorists steal many of the everyday tools that are widely available, which of course opens them up to risk of getting caught. This is why there is a considerable, and increasing, overlap between terrorism and “traditional crime” such as money laundering, drug trafficking, and even bank robbery – a favorite way of the IRA (Irish Republican Army) to raise money. Some terrorist groups have even created entire departments that specialized in forging documents. Others have made their own money.

Despite the generality of tools needed by terrorists, some attacks do, of course, require specific tools – for example, a belt or vest to carry the suicide bomber’s explosives – and it will always be important to understand what these tools might be and the supply chain that produces them.

- Facilitating Conditions

Targets, weapons, and tools exist within physical, economic, and social environments. These environments serve to enhance their use; otherwise, they would be useless. At particular points in time or in particular regions or places, conditions may arise that facilitate terrorist ability to exploit these opportunities. These conditions make it ESEER for terrorists:

Easy: When local officials are susceptible to corruption

Safe: When ID requirements for monetary or retail transactions are inadequate

Excusable: When family members have been killed by local antiterrorist action

Enticing: When local culture/religion endorses heroic acts of violence

Rewarding: When financial support for new immigrants is available from local or foreign charities

One can readily see that the characteristics of ESEER are more or less those of failed or failing states, which is why they are the preferred abode of terrorist bases. ESEER is also exacerbated by the conditions of globalization that include the worldwide marketing of small arms whether legal or illegal, porous borders between countries making movement of terrorist operatives easier, the proliferation of nuclear technology and other toxic materials creating opportunities for terrorists to obtain or manufacture WMDs, and lax international banking practices that facilitate money laundering. The global reporting of savage or violent terrorist attacks on mass media and the Internet has also probably facilitated terrorist recruitment into various terrorist organizations. It is to the organizational aspect of terrorism that we now turn.

The Situational Approach To Terrorist Groups

With some exceptions, terrorism is a group exercise, which brings with it both advantages and disadvantages to doing terrorism. The advantages include being able to (a) mount a more complex one-off mission (the Northern bank robbery by the IRA or the 9/11 attack) and (b) sustain a continued series of attacks over a long period of time (e.g., Hezbollah in the Palestinian territories). However, the majority of terrorist groups dissolve within 1 year or less. Whether they completely desist or morph into different terrorist groups is still an open question. But this important fact suggests that there are serious problems that affect the structure and dynamics of terrorist groups.

Terrorist Group Structure

There are a number of different types of organizational structure identified among terrorist groups. Much is made of their formal or informal structures, how they arose, and their similarity to other types of organizations such as business models, specialist groups for hostage taking, or cell formation to insulate members from the overall structure of the organization. The latter protects against penetration by external agents and minimizes internal group dissention and distrust.

It is also likely that developments in communication technology may mitigate the difficulties faced in organizational structure of criminal and terrorist groups. Mobile phones in particular, especially smart phones that provide cheap access to the Internet in third world countries, have made it much easier for groups to coalesce and to overcome some of the external and internal constraints of terrorist group operations. Indeed, as has occurred in the Arab spring uprisings of 2011, many of these have been fuelled by social networking technologies. Demonstrations, sometimes turning into violent uprisings, have occurred without any formal organization at all. Social networking technologies may overcome the need to maintain a lasting formal group structure. Groups can come together – almost spontaneously for a specific event – then melt away until the next occasion. However, if routine, that is, repeated, attacks are to be sustained, obviously an enduring organization is essential, made clear as the uprisings in Libya, Egypt, and Syria unfold.

Terrorist And Criminal Groups

The situational approach views terrorist attacks that are carried out by groups or at least more than one person in much the same way as any other crime. That is, it follows the commission of the crime step-by-step; it does not presume in advance that there is a particular organized hierarchical structure. For example, the 2010 book Situational Prevention of Organized Crime shows that drug trafficking, contraband cigarettes, sex trafficking, mortgage fraud, and timber theft are commonly carried out by small networks of friends or family groups who live on different sides of a national border and take advantage of marketing and trafficking opportunities that are thus available.

Groups are viewed as part of the situational environment in which decisions must be made. The extent to which decision making is facilitated or constrained when it is done by groups or in group situations rather than by individuals is a difficult question to answer, though classic research on group decision making has suggested that in groups that are not well established, there is a tendency for polarization in decision making and a shifting of decision making to converge with the views of an authoritarian leader. So the group setting is yet another factor that limits or conditions terrorists’ rational choice.

It is also important to recognize that in many, if not all instances, groups organized to commit traditional crimes (“organized crime”) such as drug trafficking and extortion, corruption of government officials already existed before terrorist groups came along. Therefore, the existence of such groups is simply another opportunity for terrorist groups to exploit, and it is logical that they would do so. There is mounting research that demonstrates the ways in which terrorist groups develop their organizational capacities as a result of the existence of organized crime and eventually collaborate, overlap with organized crime groups, or even morph in some instances into criminal groups that do organized crime. From the situational crime prevention point of view, however, it does not matter much whether what these groups accomplish is organized crime or terrorism. All we need to know is how they make their choices, what interventions will constrain them, and how working within a group organized in a particular way facilitates or constrains the choices made along the way to accomplishing the mission.

The Situational Dynamics Of Terrorist Groups

There are many sources of conflict within terrorist groups. Newman and Clarke in Outsmarting the Terrorists have identified the internal dynamics of terrorist groups that may constrain them as:

(a) The conflict between charismatic leadership and strict discipline. Charismatic leadership is probably the most significant attribute of terrorist groups and is necessary in order to transform terrorist groups into terrorist movements. It is needed to maintain faith in violence as a means to an end. But at the same time, strict discipline is needed to maintain operational security and efficiency. If charisma wanes (which we know always does), faith and thus discipline are undermined.

(b) The conflict between morality and hypocrisy. The moral contradiction between killing people (by terrorists) as a protest against killing people (by whatever enemy) is inherently a shaky morality, needing to be constantly fed by self-serving propaganda.

(c) Rules of entrance and exit. Some groups have no other rules than being a friend or family member. Others have strict rules for entry (applicants must prove themselves) and of exit – those who leave are obviously a security risk.

(d) Operational security. Complex operations require well-trained individuals who know each other well. But the more they know of each other, the more security will be jeopardized if one of them is captured.

The Situational Approach To Counterterrorism

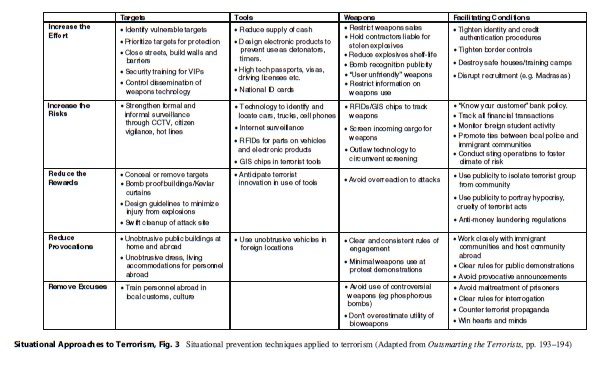

The situational approach to counterterrorism is of course focused on prevention of terrorist attacks. As in crime prevention, this is its prime objective. Over the years, situational crime prevention has accumulated a range of techniques for preventing many different types of crime. These techniques, known simply as the “Twenty Five Techniques” of crime prevention, are grounded on five psychological principles that are directed at further limiting the rational choice of the offender. Applied to preventing terrorism these are:

- Increasing the effort of mounting an attack or mission, such as protecting targets

- Increasing the risk of carrying out an attack, such as surveillance and checkpoints

- Reducing the rewards of attacks such as swift mitigation by first responders to reduce the injury and damage of attacks

- Reducing provocations of terrorists such as avoiding controversial weapons

- Removing excuses such as adopting clear rules of interrogation

If we superimpose these principles on the four pillars of terrorist opportunity, a broad array of techniques that suggest points of intervention is revealed (Fig. 3). Each of these five principles must be tailored to a specific type of terrorist attack after a step-by-step analysis has identified points of weakness.

Policy Implications

The four pillars of terrorist opportunity and the five modes of intervention that form the bases of the 25 techniques provide a framework for a systematic policy that would assess the risks of attack against various targets in various locations. After 9/11, “risk assessment” was promoted by the US Department of Homeland Security as a way of protecting against terrorist attacks. Unfortunately, because it lacked a systematic structure of how to assess comparative risks, or even what might be at risk, the major portion of resources allocated to US states by the federal government was distributed according to political largesse rather than according to a systematic comparative assessment of what was at risk. This error was in part also produced by the widespread panic by both politicians and security professionals such as Richard Clarke the then White House counterterrorism czar and reflected in the cry, “we can’t protect everything.” But the situational approach demonstrates that not all targets are equally attractive to terrorists. We do not have to protect everything, at least not to the same degree. By developing a systematic procedure for identifying risk, adequate planning and countermeasures can be set up both to prevent attacks and to mitigate the fallout of attacks should they occur. The manual, Policing Terrorism: An Executive’s Guide, by professors Newman and Clarke and published by the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, shows how this can be done by local police departments.

However, the complaint that “we can’t protect everything” reflects not only panic but also a basic misunderstanding of the situational approach to terrorism, which is that if we protect one target, the terrorist will simply shift to another target that is more easily accessible. This is called in the research literature “displacement” or the “substitution effect”. And it is the major criticism of the situational approach to crime and to terrorism.

Displacement

Echoed in The Economist on March 8, 2008, and in other trade media, the displacement criticism argues that terrorists are so committed to their violence; if they can’t attack one target, they will keep on trying until they reach another. However, we have already seen that terrorist groups, although they may be composed of committed individuals, are very likely to dissolve within a year, so the idea of commitment at least by a group to carry out an attack against anything anywhere remains highly doubtful. Furthermore, recent research in situational crime prevention by Professors Guerette and Bowers has shown clearly that displacement does not occur in some 70 % of cases studied where interventions were introduced for a wide range of crimes, and the same has been found for terrorism in respect to the effectiveness of airport security. Finally, should displacement be shown to occur, this is actually a demonstration that the intervention had an effect on the terrorists’ behavior. It means that the terrorist in displacing to a less preferred target is taking additional risks, thereby increasing the chances of being caught or thwarted in the attempt. And having to attack a target of second choice, a successful attack will produce fewer rewards to the terrorist: it may be less vital and produce less injury and damage. This leads to the final important policy implication of the situational approach to terrorism.

Attack Mitigation

If it is acknowledged that displacement may occur (not will occur), then it is possible to develop a plan of security for protection of targets that rates them according to how attractive they are to terrorists (EVIL DONE) but also the expected loss should they be attacked. This may easily be incorporated into the standard disaster response planning that occurs in most communities. Then, if a target is attacked, the fallout of that attack can be mitigated by an effective disaster response, and thus the rewards of the attack to the terrorists reduced. The importance of this mitigation should not be underrated. Certainly Al-Qaeda terrorists have understood this from the beginning. It is why they commonly include in their attacks bombs designed to disrupt the mitigating actions of first responders. It is also why they try to commit a number of attacks simultaneously. This methodology has been copied by many other terrorist groups, especially the Taliban.

The situational approach to terrorism fits nicely into the established disaster response infrastructure already established. This not only involves training of first responders, but an extensive organizational infrastructure that ensures that confusion does not occur in dealing with an attack (which occurred in the 9/11 attack) but also ensures that local communities plan systematically to protect themselves according to a rational assessment of risks. Much of this planning for protection involves regular situational crime prevention activities, well known in the field of problem-oriented policing especially partnering with businesses and local community organizations to solve crime and disorder problems.

Conclusion

In sum, the situational approach to terrorism bridges the well-known gap between the academic study of the causes of terrorism and the practical challenges of preventing and responding to terrorist attacks that are faced by policymakers, police, and security professionals. While waiting for the rest of social and political science to eradicate the root causes of terrorism, the situational approach provides a conceptual, practical, and evidence-based guide for eliminating the immediate causes of terrorist attacks.

Bibliography:

- Bullock K, Clarke RV, Tilley N (eds) (2010) Situational prevention of organized crimes. Willan/Taylor and Francis, Abingdon

- Clarke RV, Mayhew PM (1988) Crime as opportunity: a note on domestic gas suicide in Britain and the Netherlands. Br J Criminol 29:35–46, 1989

- Clarke RV, Newman GR (2006) Outsmarting the terrorists. Praeger Security International, Westport/London

- Cornish DV, Clarke RV (eds) (1986) The reasoning criminal. Springer, New York

- Freilich JD, Newman GR (eds) (2009) Reducing terrorism through situational crime prevention, vol 25, Crime prevention studies. Criminal Justice Press, New York

- Guerette RT, Bowers KJ (2010) Assessing the extent of crime displacement and diffusion of benefits: a review of situational crime prevention evaluations. Criminology 48(1):1331–1368

- Hsu H (2011) Unstoppable? A closer look at terrorism dis- placement. Doctoral dissertation, University at Albany

- Jones SG, Libicki MC (2008) How terrorist groups end: lessons for countering Al Qa’ida. RAND, Santa Monica

- Makarenko T (2004) The crime-terror continuum: tracing the interplay between transnational organised crime and terrorism. Global Crime 6(1):129–145

- Naqvi H (2012) Situational crime prevention applied to ricin and bioterrorism. In: Freilich JD, Shoham SG (eds) Special issue on policing terrorism around the globe. Israel studies in criminology, vol 11 (in press)

- Newman GR, Clarke RV (2008) Policing terrorism: an executive’s guide. USDOJ, Washington, DC

- Rapoport D (1988) Inside terrorist organizations. Columbia University Press, New York

- Rollins J, Wyler L (2010) International terrorism and transnational crime. Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC, pp 1–56

- Stohl M (2008) Networks, terrorists and criminals: the implications for community policing. Crime Law Soc Change 50(1–2):59