View sample compstat research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Since its implementation in 1994 in the United States under former Commissioner William Bratton and Deputy Commissioner, Jack Maple, of the New York City Police Department, Compstat has become widely recognized as a major innovation in US policing and abroad. Compstat is a strategic management system whose reformelements are designed to overcome some of the traditional constraints andlimitations of bureaucratic administration and make police organizations moreresponsive to changes in their crime environment. According to its doctrine, Compstat decentralizes decision-making to middle managers operating out of districts, holds these managers strictly accountable for their performance, and increases a police organization’s capacity to identify, understand, and respond to crime problems as they emerge. The evidence that Compstat reduces crime is not clear and consistent, but its originators and proponents credit Compstatwith impressive crime drops and improvements in neighborhood quality of life in New York City. Based on the publicity it has received, including a 1996 Innovations in American Policing Award sponsored by the Ford Foundation and Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, other police leaders, delegates, and politicians have flocked to New York City to observe Compstat inaction. Impressed by what they have seen, they have implemented Compstat in their own agencies. Consequently Compstat has become a global commodity andmany countries, including England, Australia, and Canada, have since adapted methods of assessing performance from the NYPD Compstat model. Research on Compstat’s relationship to another popular reform, community policing, indicates that they may work independently when implemented in the same police organization: each having little effect on the other. This suggests opportunities for their integration, but what form such a model would take is uncertain. What is clearer is that Compstat may be evolving in a new and potentially different direction. According to its supporters, “predictive policing” is an extension of Compstat’s focus on using analyses of timely crime data to drive police strategies. In this case, crime and noncrime data are made readily available and combined with forecasting, modeling, and sophisticated statistics to help make predictions about where crime is likely to occur in the future. What specific role Compstat plays in predictive policing has not been studied systematically, but this new development suggests interesting avenues for future research.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Compstat’s Doctrinal Elements And Its Diffusion

When Commissioner Bratton assumed leadership of the NYPD, his assessment of the organization was that it suffered from bureaucratic dysfunction. Functional specialization impeded coordination, an inflexible hierarchy hindered the rapid flow of information, timely crime data were unavailable, and the department had lost sight of its overarching mission, namely, to reduce serious crime (Bratton and Knobler 1998: 209; Silverman 1999). To streamline operations, Bratton borrowed state-of-the-art management doctrines espoused by organizational development experts in the private sector. These principles included a commitment to establishing priorities, finding creative approaches to new challenges, and using information scientifically to drive decision-making (Willis et al. 2007). According to this “reengineering” approach (Hammer and Champy 1993), successful organizations respond to uncertainties in their environments by reprioritizing their goals and revamping core structures for their successful accomplishment. Compstat, whose name comes from a computer file name, was the centerpiece of Bratton’s reform efforts (Silverman 2006: 221).

At the core of NYPD’s Compstat model are four crime reduction elements that are designed to make police organizations rational and more responsive to management direction: (1) accurate, timely information made available at all levels in the organization; (2) selection of the most effective tactics for specific problems; (3) rapid focused deployment of people and resources to implement those tactics; and (4) relentless follow-up and assessment to learn what happened and make subsequent tactical assessments if necessary (Bratton and Knobler 1998). Fundamental to this Compstat approach is the delegation of decision-making authority to middle managers (or precinct/district commanders) with territorial responsibility. These commanders are then held directly accountable for reducing crime in their precincts and given the necessary resources (specialist units, detectives, etc.) for accomplishing this goal.

Alongside these elements, the NYPD also developed eight crime control and quality-oflife strategies that were disseminated throughout the department. Their primary purpose was to provide commanders with guidance on how to craft specific approaches to reduce crime and disorder problems in their precincts, including youth violence, drug and gun crimes, and public nuisances such as “squeegee window washers” (Safir, n.d.: 6). However, case studies on Compstat in other departments suggest these features of the NYPD model have not been as widely implemented as its frequent “crime control strategy meetings” that are the centerpiece of the Compstat process (Willis et al. 2007). During these meetings precinct commanders appear before the department’s top echelon to report on crime problems in their districts and what they are doing about them. This occurs in a datasaturated environment where crime analysts collect, analyze, and map crime statistics to spot crime trends and help precinct commanders identify patterns among crime incidents. Top administrators then use this information to quiz district commanders on the crime in their beats and to hold them responsible for solving them. Failure to provide satisfactory responses to their inquiries may lead to stern criticism or possibly removal from command. Based on what those who developed Compstat have written, as well as what those who have studied Compstat have observed, researchers have identified six core elements that have emerged as central to the development of Compstat (Weisburd et al. 2003):

• Missionclarification. Top management is responsible for clarifying and promoting thecore features of the department’s mission. Mission clarification includes ademonstration of management’s commitment, such as stating those goals inspecific terms for which the organization and its leaders can be held accountable – for example, reducing crime by 10 % in a year.

• Internal accountability. Operational commanders are held accountable for knowing their commands, being well acquainted with the problems in the command, and accomplishing measurable results in reducing those problems – or at least demonstrating a diligent effort to learn from that experience. Those who fail to do so can suffer adverse career consequences such as removal from command.

• Geographic organization of operational command. Operational command is focused on the policing of territories, so central decision-making authority about police operations is delegated to commanders with territorial responsibility (e.g., districts). Functionally differentiated units and specialists (e.g., patrol, community police officers, detectives, vice) are either placed under the command of the district commander or arrangements are made to facilitate their responsiveness to the commander’s needs.

• Organizational flexibility. The organization develops the capacity and the habit of changing established routines to mobilize resources when and where they are needed for strategic application.

• Data-driven problem identification and assessment. Crime data are made available to identify and analyze problems and to track and assess the effectiveness of the department’s response.

• Innovative problem-solving tactics. Police responses are selected because they offer the best prospects of success, not because they are “what we have always done.” In this context, police are expected to look beyond their own experiences by drawing upon knowledge gained in other departments and from innovations in theory and research about crime prevention.

On occasion, this listhas been expanded to include a seventh Compstat element or “externalaccountability.” This refers to Compstat’s capacity for making police decision-makingmore transparent to the public. Under Compstat, departments are externally accountable to the degree that they provide stakeholders with accurate andtimely information about how well they are accomplishing their official crime controlmission.

Evidence suggests that Compstat has diffused rapidly. In a national survey of large (>100 sworn) police departments in the USA administered by the Police Foundation in 2000, a third of agencies reported they had implemented a Compstat-like program with a quarter claiming they were intending to do so. This study confirmed that Compstat had “literally burst onto the American policing scene” and was following a diffusion process as rapid as “innovations in other social and technological areas” (Weisburd et al. 2004: 15). Nor does the spread of Compstat appear to be slowing, according to another survey conducted in 2006 by scholars at George Mason University and funded by the Department of Justice’s Office of CommunityOriented Policing Services, 60 % of large police departments in the USA had implemented Compstat or a Compstat-like program (Willis et al. 2010a).

Compstat In Practice

It is virtually a truism in organizational theory that organizational change, including police reform, rarely works in intended ways. Accounts of the New York City Police Department suggest that Compstat’s elements function like a well-oiled machine (Henry 2002; McDonald et al. 2002), but others characterize these evaluations as “advocacy” studies that lack rigorous scientific analysis by disinterested observers (Jang et al. 2010). A small but rich body of systematic research in other police departments that have sought to replicate the NYPD model has revealed some unintended effects and internal paradoxes in how it operates (Willis et al. 2007; Dabney 2010).

Using data from surveys sent to a stratified sample of 615 police agencies nationwide, Weisburd et al. (2003) concluded that Compstat reinforces the paramilitary model of police organizations. Most notably, Compstat appeared to strengthen the command hierarchy by making middle managers more responsive to top leadership direction through fear of punishment for poor performance. This finding was significant because it showed that Compstat appeared to preserve, rather than transform, the “bureaucratic” or “paramilitary” model of police organization criticized by reformers as too rigid and punitive. Follow-up fieldwork at three police agencies of different size and geographic location confirmed the survey finding that Compstat’s accountability mechanism was generally the element most strongly implemented, along with a clear crime control mission and the display of crime statistics and maps at regular Compstat meetings (Willis et al. 2007). To some this could be interpreted as clear evidence of significant police reform. Compared to past police practices, Compstat reinforced the police crime-fighting mission, held middle managers more accountable for performance, and advanced the timely use of crime data in decision-making. These changes notwithstanding, the fact that departments had placed less emphasis on other key Compstat elements (geographic organization of operational command, organizational flexibility, and innovative problem-solving strategies) tempered any claims of radical change under Compstat.

One possible explanation for Compstat’s uneven implementation in these three agencies was that those elements of Compstat that were most likely to be adopted were also those that were most likely to help the agency to appear progressive in the eyes of powerful stakeholders in the agency’s environment (e.g., local politicians, community leaders, citizens’ groups). Like many public organizations, police agencies that appeal to powerful values and beliefs in their environment about what police structures and practices should look like stand to gain legitimacy and increase their chances of survival and of securing valuable resources. Increasing the agency’s attention to crime control, the spectacle of weekly performance evaluations, and glitzy displays of crime statistics help give the powerful impression that these three departments were doing something to reduce crime even though other structures designed to strengthen this focus remained fundamentally unaltered. Those elements which were least likely to be implemented were also those that represented the greatest departure from taken-for-granted beliefs about how police organizations should operate. So, for example, favoring experimentation with different problem-solving approaches over traditional law enforcement responses to crime could expose the organization to risk (as innovations rarely succeed the first time) and challenge widely held expectations that the primary role of the police is to engage in preventive and reactive patrol and make arrests.

An in-depth case study of one police department applying Max Weber’s conceptualization of the modern bureaucratic organization to Compstat also revealed a paradox in how Compstat operated: the power of Compstat’s accountability mechanism undermined several of its other elements including collaboration (by fostering competition) and innovation (by shrinking tolerance for failure). This case study also revealed how Compstat’s strategic approach to adapting quickly to emerging crime problems clashed with classic bureaucratic structures for maintaining efficient routines (such as clear lines of authority and stable job assignments) (Willis et al. 2004).

Compstat’s Effect On Crime

Compstat’s implementation in the NYPD corresponded to a greater drop in New York City’s crime rate than the national average. According to Silverman, “During 1994, the overall New York City crime decline was 12 %, compared to 2 % nationally, and 17 % for 1995” (Silverman 1996: 1). Its supporters claimed that this was clear evidence of Compstat’s success as a mechanism for reducing crime and improving neighborhood quality of life (Bratton and Knobler 1998), but the association between Compstat and declining crime levels does not necessarily imply causation. Subsequent research seeking to assess Compstat’s effect on crime suggests a more complicated picture. This is owed in no small measure to the fact that Compstat often combines agency reorganization with the implementation of a wide range of crime control strategies (e.g., order maintenance policing, zero tolerance policing, hot spot policing) making it difficult to identify the specific Compstat mechanism responsible for any crime reduction.

Applying the same descriptive analyses used by its supporters, Eck and Maguire challenge the claim that Compstat played a key role in reducing serious crime in New York City (2000). They examine data from the United States’ Uniform Crime Reports between 1986 and 1998 and show that the decline in New York’s homicide rate began long before Compstat was implemented. They also note that other large cities experienced significant declines in their homicide rates during the early to mid-1990s but had not implemented a Compstat program. For example, San Diego, San Antonio, and Los Angeles all experienced sharp drops in their homicide and violent crime rates during this period (Harcourt 2001). Eck and Maguire conclude, “On balance, the data do not support a strong argument for Compstat causing, contributing to, or accelerating the decline in homicides in New York City or elsewhere” (2000: 233). Similarly, Willis et al. using a simple pre-/posttest noted that crime was already in decline at the agencies where they conducted their on-site fieldwork and the rate of decline was the same or less steep following Compstat’s implementation (2007).

More rigorous attempts to assess Compstat’s effectiveness as a crime control strategy do not provide clear and consistent results. Using piecewise linear growth models, Rosenfeld et al. (2005) examined the impact of three law enforcement initiatives, including Compstat, on homicide trends in three cities while making systematic comparisons to crime trends in other cities and controlling for other factors influencing crime trends (e.g., measures of social and economic disadvantage and police density). Based on their analysis, they concluded that there was insufficient evidence in support of the NYPD Compstat model’s impact on homicide trends. Others are also skeptical of Compstat’s capacity to reduce crime (Dixon 1998; Chilvers and Weatherburn 2004).

Recent studies in Queensland, Australia, and Fort Worth, Texas, are more sanguine. They use time-series analyses to assess the impact of Compstat on crime. In Queensland, Compstat’s management accountability features were combined with a problem-oriented policing approach, but this was not the case in Fort Worth. Using crime data spanning a 10-year period (1995–2004 inclusive), the Queensland study concluded that Compstat generally reduced reported crime and was cost effective, but it was most effective at reducing property-related offenses. Similarly in Fort Worth, Compstat significantly decreased property and total index crime rates but had little effect on violent crime rates. What still remains unclear are the independent effects of the different elements of the multidimensional Compstat process (e.g., accountability, crime analysis, order maintenance strategies) on crime.

In summary, when combining these findings on Compstat with a growing body of evidence on police effectiveness, it appears that when Compstat’s accountability and performance measurement structures support the implementation of police practices targeted and tailored toward specific offenses, offenders, or places, Compstat can lead to reductions in crime and disorder (Braga and Bond 2008: 599).

Compstat’s Relationship To Community Policing

Compstat has emerged during the same period as community policing, another popular engine of police reform in the USA and around the globe. Community policing can be characterized as a philosophy and an organizational strategy designed to reduce crime and disorder through community partnerships, problem solving, and the delegation of greater decision-making authority to patrol officers and their sergeants at the beat level. It varies more than Compstat from place to place in response to local problems and community resources. Given the visibility of these reforms, it is natural to consider the relationship between the two when they are implemented in the same police organization: do they operate together, that is, one reinforcing the other, or are there points of conflict, where pursuing one makes it harder to pursue the other successfully? Alternatively, do they work separately, that is, each having little consequence for the other? Some have claimed that Compstat complements and supports community policing and even improves it (McDonald et al. 2002). According to this perspective, both reforms share the same concern with crime and quality-of-life offenses and seek to decentralize operations geographically. Where there are discrepancies, such as community policing’s weakly developed accountability mechanism, the other reform is simply able to compensate.

A second group of researchers is less convinced that these reforms are compatible. Wesley Skogan, a well-known researcher on community policing, has commented on the tensions between Compstat’s data-driven accountability elements and the different currents that push community policing in the opposite direction (2006). Community policing’s focus on local neighborhood problems, developing police-community partnerships, and creative problem solving at the grassroots level are not key features of Compstat as it has evolved. It is also possible that these reforms operate independently from one another in order to minimize conflicts to existing organizational structures and routines.

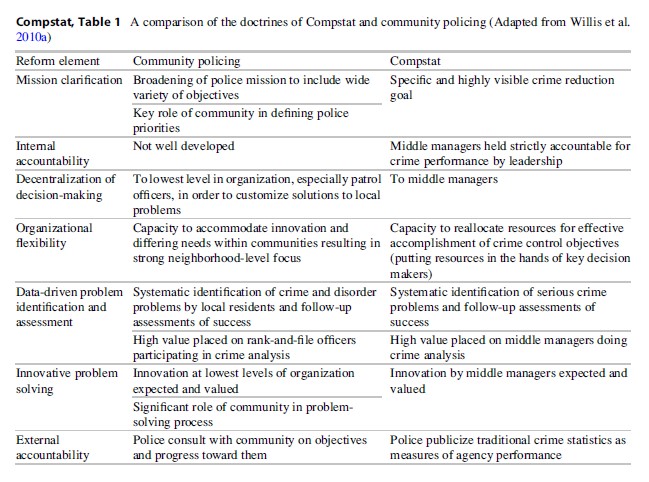

The body of empiricalresearch on this issue is very small. Willis et al. identify seven coreelements that the full implementation of Compstat and community policingdemands and assess where their respective reform doctrines stand on theseelements (see Table 1). Briefly, Compstat focuses the police mission narrowlyon serious crime, while community policing broadens it to include a widervariety of objectives including community problems, reductions in social andphysical disorder, and citizens’ fear of crime. Furthermore, in contrast toCompstat, community policing requires that community members play a key role indefining what the police should be trying to accomplish.

When it comes to making people feel responsible for their performance, Compstat is first and foremost a method to hold middle managers accountable for knowing what is going on in their areas and for devising timely, effective solutions to the most pressing problems. By contrast, there is less concern in the community policing literature with holding police feet to the fire of accountability.

Both community policing and Compstat promote decentralizing decision-making authority, but Compstat concentrates on the delegation of authority to middle managers, while community policing has been far more interested in decentralizing decision-making to those responsible for doing the lion’s share of the police organization’s work: the rank and file.

Organization flexibility refers to a department’s capacity to determine where a problem is and to change or disrupt department routines to do this. Community policing requires flexibility to meet the varying demands of different constituencies, while Compstat requires flexibility to put the key resources in the hands of the right people and to alter procedural routines to do what must be done to be effective in controlling crime.

Both reforms emphasize the use of timely data to drive decision-making, but there are some important differences. Compstat relies on a department’s existing data systems to focus attention on serious crime, while community policing solicits input from community residents to identify a broader range of minor crimes and social disorder deserving of police attention. Moreover, community policing places higher value on sergeants and patrol officers participating in crime analysis, unlike Compstat which empowers district commanders to identify and analyze problems.

Under Compstat and community policing, crime data are supposed to provide a basis for searching and implementing creative solutions to crime and disorder problems. Where they differ is that Compstat assigns most of this responsibility to middle managers using traditional crime and calls-for-service data, while community policing emphasizes the role of rank-and-file officers and the public in using customized sources of data and information to tailor specific solutions to local neighborhood problems.

Finally, Compstat and community policing’s attempts to make police operations more transparent work in different ways. Under Compstat, departments are externally accountable to the degree that they provide stakeholders with accurate and timely information about how well they are accomplishing their crime control mission. According to community policing doctrine, external accountability goes far beyond merely providing citizens with standard crime measures. Under this model, police are accountable to the degree that they create a collaborative environment with local residents that is directly responsive to their concerns and to the degree that they foster an open dialog on what the police are doing and how well they do it.

Based primarily on observations conducted from 2006 to 2007 at seven police agencies in the USA, Willis et al. describe how Compstat and community policing operated in relation to each of these core elements and assessed their level of integration (not at all integrated, low, moderate, or high). They concluded that Compstat and community policing operated largely independently from each other. Their simultaneous operation helped departments respond to a broader set of goals and wider variety of tasks than had they implemented just one reform. So, for example, community policing provided opportunities to meet with community groups and identify their concerns, while Compstat helped focus the police organization’s energies on fighting crime. However, those problems identified as most pressing by communities were rarely subject to the kind of intense and systematic scrutiny at regular Compstat meetings as serious crime. These findings provided the basis for recommendations on how Compstat and community policing might be integrated in order to be mutually reinforcing (e.g., constructing measures of community policing that can be prioritized, measured, and reported on at regular Compstat meetings) (Willis et al. 2010b). However, to date, these recommendations have not been subjected to empirical testing and thus remain speculative.

Predictive Policing And Future Research

At the time of this writing (2012), Compstat’s emphasis on using timely crime data to address current crime problems may be evolving into a policing approach that attempts to forecast trends and then prevent crime from occurring in the future (Bratton and Malinowski 2008: 264). Currently in the stages of its early development, this model known as “predictive policing” uses “advanced analytics” in an attempt to anticipate or predict crime and act as a guide to “risk-based deployment” (Beck and McCue 2009: 19–20). Its elements include integrating crime data with other information sources inside and outside of the police agency (e.g., economic data on housing foreclosures); analyzing these data to identify and anticipate crime patterns related to people, places, or events; mobilizing resources; implementing strategies in response to these predictions; and linking accountability to performance targets rather than just past outcomes (Bratton et al. 2009). Similar to Compstat, this model draws on market practices commonly used in the private sector and specifically attempts to understand and predict consumer behavior. Companies like Walmart use business analytics to forecast demand and then make adjustments to their supply lines so that any increase in demand can be met successfully (Beck and McCue 2009). So, for example, in the event of a large weather event like a hurricane, Walmart stores stock up in advance on water, batteries, and other items to ensure that they have adequate supplies available.

According to Charlie Beck, Chief of the Los Angeles Police Department where predictive policing originated, “the predictive vision moves law enforcement from focusing on what happened to focusing on what will happen and how to effectively deploy resources in front of crime, thereby changing outcomes” (Pearsall 2010).

The emergence of predictive policing opens up a rich vein of research opportunities including questions about the nature of its implementation in different police agencies and its effectiveness in reducing crime. Early anecdotal evidence regarding the latter is encouraging. The Santa Cruz Police Department in California reported an 11 % drop in burglaries for the 5-month period following the implementation of its predictive policing model compared to the same period the previous year. This model runs historical data on the location and time of burglaries through an algorithm. This then generates a list of locations and times with the highest probability of burglaries and auto thefts that is distributed to officers at roll call (Baxter 2011).

Any evaluation of predictive policing should also include an assessment of the consequences of its adoption on the legitimacy of the police in the eyes of citizens and other community stakeholders. Of particular concern here should be the degree to which predictive policing heralds a more pronounced move toward the profiling of certain types of people than has been observed under its predecessor. Given predictive policing’s potential to link police databases with a variety of other information systems, such as the census, schools, or social services, the likelihood increases that specific groups will be targeted for additional police attention. Not only will this likely exacerbate existing racial disparities in the American criminal justice system, it also advances a troubling conception of justice and constitutional rights based on the risk of future offending rather than past practice (Harcourt 2007: 3). Some have suggested that predictive policing might unintentionally undermine the Fourth Amendment protections for some individuals (Ferguson 2011). Under current law in the USA, police officers can stop someone based on “reasonable suspicion” that a crime is being, has been, or is about to be committed. According to the Supreme Court, an important contextual factor for determining reasonable suspicion is whether or not the stop occurs in a high-crime area. Thus predictive policing opens up the possibility that individuals living, visiting, or working in such areas will “have a lesser expectation of privacy than those in other non-high crime neighborhoods” (Ferguson 2011: 1).

It might be that the promise of crime analysts applying advanced statistical methods to vast amounts of data, thereby improving the accuracy of results, convinces police chiefs that this is a viable crime prevention strategy. An alternative possibility is that ethical concerns about predictive policing’s analytic methods being used “to target individuals inappropriately for future crimes, or bad acts that they may commit but have not” could impede its progress (Beck and McCue 2009:23). Either way, the emergence of predictive policing presents an intriguing case for an assessment of Compstat as it appears to be developing, one that may lead to important empirical and theoretical insights about the changing nature of crime control policy and practice in the contemporary USA and elsewhere.

Bibliography:

- Beck C, McCue C (2009) Predictive policing: what can we learn from Walmart and Amazon about fighting crime in a recession? Police Chief 76:18–24

- Braga A, Bond B (2008) Policing crime and disorder hot spots: a randomized controlled trial. Criminology 46:577–607

- Bratton WJ, Knobler P (1998) Turnaround: how America’s top cop reversed the crime epidemic. Random House, New York

- Bratton WJ, Malinowski SW (2008) Police performance management in practice: taking Compstat to the next level. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 2:259–265

- Bratton WJ, Morgan J, Malinowski S (2009) Fighting Crime in the Information Age: The Promise of Predictive Policing. Discussion draft, November 18. Available online: https://publicintelligence.net/lapd-research-paper-fighting-crime-in-the-information-age-the-promise-of-predictive-policing/

- Baxter S (2011) Santa Cruz Police Have Success With Predictive Policing. Santa Cruz Sentinel, July 18. Available online: https://www.santacruzsentinel.com/2011/07/18/santa-cruz-police-have-success-with-predictive-policing/.

- Chilvers M, Weatherburn D (2004) The New South Wales Compstat process: its impact on crime. Aust N Z J Criminol 37:22–28

- Dabney D (2010) Observations regarding key operational realities in a Compstat model of policing. Justice Quarterly 27:28–51

- Dixon D (1998) Broken windows, zero tolerance, and the New York miracle. Current Issues in Criminal Justice 10:96–106

- Eck J, Maguire ER (2000) Have changes in policing reduced violent crime? An assessment of the evidence. In: Blumstein A, Wallman T (eds) The crime drop in America. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 207–265

- Ferguson AG (2011) Predictive policing and the fourth amendment. Am Crim L Rev. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2050001

- Hammer M, Champy J (1993) Reengineering the corporation: a manifesto for business revolution. Harper Business, New York

- Harcourt BE (2001) Illusion of order: the false promise of broken windows policing. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Harcourt BE (2007) Against prediction: profiling, policing, and punishing in an actuarial age. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Henry VE (2002) The Compstat paradigm: management accountability in policing, business, and the public sector. Looseleaf Publications, New York

- Jang H, Hoover LT, Joo H-J (2010) An evaluation of Compstat’s effect on crime: the forth worth experience. Police Quarterly 13:387–412

- Mazerolle L, Rombouts S (2007) The impact of COMPSTAT on reported crime in Queensland. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies and Management 30:237–256

- McDonald P, Greenberg SF, Bratton WJ (2002) Managing police operations: implementing the New York crime control model, Belmont, CA

- Pearsall B (2010) Predictive policing: the future of law enforcement? NIJ Journal 266:16–19

- Rosenfeld R, Fornango R, Baumer E (2005) Did Ceasefire, COMPSTAT and Exile Reduce Homicide? Criminol Publ Pol 4:419–450

- Safir H (n.d.) The Compstat process. Office of Management and Planning, NYPD

- Silverman EB (1996) Mapping change: how the New York City police department re-engineered itself to drive down crime. Law Enforcement News 15:1

- Silverman EB (1999) NYPD battles crime: innovative strategies in policing. Northeastern University Press, Boston

- Silverman EB (2006) Compstat’s innovation. In: Weisburd D, Braga A (eds) Police innovation: contrasting perspectives. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 267–283

- Skogan WG (2006) Police and community in Chicago: a tale of three cities. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Weisburd D, Mastrofski SD, McNally AM, Greenspan R, Willis JJ (2003) Reforming to preserve: COMPSTAT and strategic problem solving in American policing. Criminol Publ Pol 2:421–456

- Weisburd D, Mastrofski SD, Greenspan R, Willis JJ (2004) The growth of Compstat in American policing. Police Foundation, Washington, DC

- Willis JJ, Mastrofski SD, Weisburd D (2004) COMPSTAT and bureaucracy: a case study of challenges and opportunities for change. Justice Quarterly 21:463–496

- Willis JJ, Mastrofski SD, Weisburd D (2007) Making sense of COMPSTAT: a theory-based analysis of organizational change in three police departments. Law and Society Review 41:147–188

- Willis JJ, Kochel TR, Mastrofski SD (2010a) The co-implementation of Compstat and community policing: a national assessment. Department of Justice, Office of Community-Oriented Policing Services, Washington, DC

- Willis JJ, Mastrofski SD, Kochel TR (2010b) Recommendations for integrating Compstat and Community Policing. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 4:182–193