View sample public relations research paper on international public relations. Browse public relations research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

On the eve of the 21st century (December 31, 1999), CNN aired live coverage showing how people throughout the world celebrated the New Year at the dawning of a new millennium. Thanks to satellite broadcasting, this 100-hour television event showed a wide variety of festivities at more than 50 locations in the world, including Times Square in New York City, the Red Square in Russia, the Eiffel Tower in Paris, and many other corners of the globe. This coverage was available to about 1 billion people in more than 200 countries and territories. It is undeniable that mass media plays an important role in providing the social perception of globalization.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In business, globalization is an effective and powerful strategy for businesses striving to be prosperous. Accelerated by global competition and free-trade developments such as WTO (World Trade Organization) and OECD (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development), corporations are eager to create new markets abroad, as well as to find ways to lower production costs. In 1996, for example, more than 8,000 U.S. companies had international operations in foreign countries. Alternatively, more than 8,000 foreign firms operated in the United States. Foreigners have invested more than $300 billion in the United States in joint ventures and direct investment (Porter & Samovar, 1996). As this trend keeps accelerating, the current world economy becomes more closely connected than ever.

What does this wave of globalization mean to public relations? One of the most frequently cited definitions of public relations is “the management function that establishes and maintains mutually beneficial relationships between an organization and the publics on whom its success and failure depends” (Cutlip, Center, & Broom, 2005, p. 6). Many organizations today, both for profit and not-for-profit, operate globally, and the success or failure of their organizational goals and objectives depends on their publics, domestically as well as overseas. The assumptions and principles that organizations hold when practicing public relations in one country may not be applicable when practicing public relations in another country. Even the definition of public relations can be substantially different from country to country. The growing interest in international public relations comes out of the new challenge that practitioners and scholars face—the international and global environment where public relations operates.

The purpose of this research paper is to introduce the key conceptual developments in international public relations, some major areas of application, and a representative case of multinational organization.

Conceptual Development of International Public Relations

Even as interest in international public relations as a subarea of public relations continues to grow, there has been confusion over the concept of international public relations. To some, there is no such thing as international public relations, and to others, international public relations is “one of the fastest-growing areas in this field” (Vasquez & Taylor, 2001, p. 331). International public relations is a relatively new subarea of public relations that suffers from the lack of theoretical foundations because public relations itself is still a growing area in the field of mass communications. As Kunczik (1997) pointed out, most articles on international public relations have been based on anecdotal or descriptive approaches, even “scientifically non-serious sources” (p. 24). Wakefield (1996) emphasized that “most of the attempts at scholarly examinations have been country-specific, discussing public relations in a particular country and how it varies from other countries” (p. 18).

To some extent, much international public relations research can be labeled as descriptive because it explores public relations practices in different countries and geographic regions without applying overarching theories and conceptualization. In the early stage of developing the field of international public relations research, a case study approach provides valuable knowledge about what others have accomplished in the field. However, isolated cases alone limit our understanding of international public relations. The current trend is toward more studies based on theoretical frameworks.

Wakefield (1996) identified four theoretical domains for international public relations. They are global society theories, cultural theories, management theories, and communication theories. He suggests that international public relations can benefit from these areas in building theoretical frameworks.

Grunig and his colleagues (J. E. Grunig, 1992; Grunig, Grunig, & Dozier, 2002; Grunig, Grunig, & Vercic, 1998; Vercic, Grunig, & Grunig, 1996; Wakefield, 1996) provide a good example of advancing these ideas in their research. They proposed a normative theory of global public relations excellence by combining their original IABC (International Association of Business Communicators) excellence theory (public relations framework) and a structured flexibility theory (management framework; Brinkerhoff & Ingle, 1989). This seminal study identified key characteristics of excellence in public relations as general principles. Their argument was that excellence characteristics of public relations identified by the IABC study hold true not only for the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada (where original observations occurred) but also for other countries; however, contextual factors should be considered when applying these generic principles (specific application).

The generic principles of public relations excellence are (1) involvement of public relations in strategic management, (2) empowerment of public relations in the dominant coalition or a direct reporting relationship to senior management, (3) an integrated public relations function, (4) public relations as a management function separate from other functions, (5) PR head’s managerial leadership, (6) a two-way symmetrical model of public relations, (7) a symmetrical system of internal communication, (8) the PR department’s knowledge potential for a managerial role and symmetrical public relations, and (9) diversity embodied in all roles (Vercic, Grunig, & Grunig, 1996).

Involvement of public relations in strategic management means that public relations plays a significant role in identifying organizational goals, leading communication management to achieve those goals, and, most important, building good relationships with strategic publics both internally and externally. Empowerment of public relations in the dominant coalition or a direct reporting relationship to senior management means that the public relations unit and the public relations head should be a part of a powerful group of managers who are responsible for strategic decisions for the organization. Integrated public relations function means that public relations functions should be operated by a single unit or by a coordinating system. Only this integrated system can adapt to changing strategic publics. Public relations as a management function from other functions means that the public relations unit should be independent from other organizational units. In many organizations, public relations functions are subdued to other units (e.g., marketing, law, consumer management, human resource, advertising), which makes public relations less effective. Simply put, communicating with publics is different from dealing with markets. The role of the public relations practitioner means that excellent public relations can be secured by a managerial role (strategic program management) not by a technician role (writing and editing publications). Two-way symmetrical model of public relations means that excellent public relations uses social scientific research to communicate with strategic publics and actively seek out a mutually beneficial relationship (win-win zone) with them. Mutual understanding is a key purpose of communication. Symmetrical system of internal communication means that excellent organization allows autonomy to employees and creates participatory organizational culture to increase job satisfaction. Knowledge potential for a managerial role and symmetrical public relations means that excellent public relations practitioners should have acquired a body of knowledge in public relations and be active in professional development. Diversity embodied in all roles means that an excellent public relations unit needs variety to effectively communicate with diverse publics in society. Diversity in gender, racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds is highly pursued (Vercic, Grunig, & Grunig, 1996).

Specific contexts for applying the general principles are (1) the level of development in a country, (2) the local political situation, (3) the cultural environment, (4) language difference, (5) the potential for activism, and (6) the role of the mass media (Grunig, Grunig, & Dozier, 2002). These contexts are defined and elaborated in detail by Sriramesh and Vercic (2003).

Sriramesh and Vercic (2003) elaborated on these specific contexts (environmental variables) in moving international public relations research to the next level. As for political systems, they found democracy and political freedom as very important factors in the growth of public relations because “strategic public relations flourishes in pluralistic societies” (p. 5). Also of interest to Sriramesh and Vercic is how other types of political systems, such as authoritarian regimes (e.g., China), affect public relations. As for economic development, Sriramesh and Vercic (2003) found that economic prosperity and private entrepreneurship are crucial for the growth of public relations. Activism is considered as both an opportunity as well as a threat to public relations professionals. Organizations can transform and innovate themselves to meet change pressures from activist groups, and as a consequence, they can be more competitive and socially responsible. However, the opposite consequence occurs when organizations fail to successfully adapt to this pressure from activist groups. Public relations in any particular country is influenced by the societal and organizational culture within that country. Knowing cultural norms and assumptions at both the national and the organizational levels is crucial to every stage of strategic planning for public relations. Media environment can be elaborated on by examining three dimensions of media: (1) media control (Who owns the media?), (3) media access (Who can access the media?), and (3) media outreach (Who consumes the media?). All three dimensions vary from country to country. Public relations professionals need to know this environment in a given society because the media is a powerful conduit to influence the target publics.

To test these normative propositions of generic principles and specific contexts, Grunig, Grunig, Sriramesh, Huang, and Lyra (1995) did a meta-analysis of research in India, Greece, and Taiwan and concluded that “the models must be generic to all cultures and that an approach to public relations that contains at least elements of the two-way symmetrical model may be the most effective in all cultures” (p. 182). Similar findings are supported by Grunig, Grunig, and Vercic’s (1998) study of Slovenian firms, Wakefield’s (2000) Delphi panel study, and Rhee’s (2002) study of public relations practitioners in Korea.

More recently, Curtin and Gaither (2007) introduced the circuit-of-culture model as a theoretical framework for international public relations. Taking a broader definition of culture (a crucial concept to international public relations), they identified five moments of “cultural space in which meaning is created, shaped, modified, and recreated” (p. 38). These moments of cultural space are labeled as moments of regulation, production, representation, consumption, and identity. The moments are closely interrelated to create meaning without any prescribed direction of relationships.

The moment of regulation is defined as “controls on cultural activity ranging from formal and legal controls, such as regulations, laws, and institutionalized systems, to the informal and local controls of cultural norms and expectation” (p. 38). This definition is similar to that of the contextual factors or environmental variables as applied to public relations operations. The moment of production “outlines the process by which creators of cultural products imbue them with meaning, a process often called encoding” (p. 39). For example, technological constraints and organizational culture influence the process of planning public relations campaigns. The moment of representation is “the form an object takes and the meanings encoded in that form” (p. 40). The moment of consumption is “when messages are decoded by audiences . . . target publics in public relations bring their own semantic networks of meaning to any communicative exchange” (p. 40). Identities are “meanings that accrue to all social networks, from nations to organizations to publics” (p. 41). The authors were able to use this framework to explain various cases of international public relations issues and campaigns, which establishes this framework as a good example of theory-based international public relations research.

Along with theory-based studies, case studies continue to expand our understanding of public relations in other parts of the world. This is called a culture-specific approach, focusing on documenting the peculiar and distinct features of individual cultures. The main focus of these studies concerns how social, political, and economic contexts influence the practices of public relations country by country. For example, books titled International Public Relations: A Comparative Analysis, edited by Culbertson and Chen (1996), The Global Public Relations Handbook: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by Sriramesh and Vercic (2003), and Handbook of Public Relations, edited by Heath (2001) include a lot of excellent case studies using this approach. Other examples include a meta-analysis on public relations in India, Korea, and Japan (Sriramesh, Kim, & Takasaki, 1999), the HIV/AIDS issue and Thailand public (Chay-Nemeth, 2001), the nation building in Malaysia (Taylor, 2000), and the image of public relations in Korean newspapers (Park, 2001).

Major Areas of International Public Relations

Public Relations and Multinational Organizations

Stohl (2001) examined the effects of globalization on organizations by introducing five types of organizations according to predominant national orientation: (1) domestic, (2) multicultural, (3) multinational, (4) international, and (5) global. These definitions can help us understand concepts related to “global” in the organizational context. A domestic organization has identification with one country and one dominant culture. A multicultural organization has identification with one country but a culturally diverse workforce. A multinational organization has identification with one nationality while doing business in several countries. It has a multinational workforce, management, clients, and environment; however, it represents one national interest. An international organization has identification with two or more countries, each of which has distinct cultural attributes. Workforce, management, and clients are recognized as representing diverse national interests. Finally, a global organization has identification with the global system transcending national borders and is basically a stateless organization. In a global organization, organizational membership supersedes national orientation.

In the early stages of globalization, we observed many multinational organizations. But as globalization progresses, we begin to see more international and global organizations. With dramatic technological advancement in transportation and communication, even the distinction between domestic and international blurs. For most people, multinational, international, and global organizations are considered as one category, although there may be disagreement on what to label the category.

One of the biggest challenges facing multinational organizations is dealing with more diversified publics and stakeholders. Consider Mattel’s toy recall in 2007. The company announced several recalls, totaling some 21 million toy products, from the global market due to the presence of excessive levels of lead paint and tiny harmful magnets that could be swallowed. First and foremost, Mattel’s reputation was enormously damaged among many angry parents who were deeply concerned about the safety of their children. Governments and regulatory bodies in Asia, Europe, and other parts of the globe raised safety inspection standards due to this incident. Investors sold out Mattel shares, and stock price quickly plunged.

Mattel’s initial response was not a good example of crisis public relations because they put much of the blame on Chinese manufacturers and the inadequacies of the Chinese regulation system. It created a lot of concerns about madein-China products among consumers worldwide due to its tainted image triggered by Mattel’s toy recall. Fingerpointing at others without sufficient supporting evidences turned out to be detrimental to Mattel. As the public soon learned, there were a substantial number of mistakes and problems on Mattel’s side, such as product design deficiencies and inadequate safety guidelines. Mattel’s top executives should have flown to China and apologized to the Chinese leaders and business partners for making such a hasty judgment. The worldwide media coverage of this scandal could not have been more negative, and recovery from this ordeal will seemingly be a tough uphill battle for Mattel for many years to come. Trust can be easily lost but is hard to rebuild.

Corporations are not the only form of multinational organizations. Many nongovernment organizations (NGOs, hereafter) promote their cause globally. For example, Green Peace international is headquartered in the Netherlands and has branch offices in 42 countries and regions. They are very active in influencing environment policy at the national and global levels, and their public relations campaigns often attract worldwide attention.

Consider the antiglobalization demonstration in Seattle in 1999. Activist groups throughout the world organized themselves around the event of the meeting of the WTO in Seattle to express their anti-WTO message to the world.

There are no national borders in cyberspace. Local NGOs or even individual blogs can get international attention overnight. Sony and Dell had to recall their notebook batteries when a few consumers uploaded video clips of burning laptops onto YouTube. The images spread quickly throughout cyberspace, gaining nearly immediate international attention. As the world has virtually shrunk, environmental scanning becomes more and more challenging for public relations professionals.

Public Diplomacy and National Reputation

Public diplomacy (Kunczik, 1997; Signitzer & Coombs, 1992) has some implications in the developing field of international public relations. Signitzer and Coombs (1992) described international public relations as

mainly concerned with practical problems arising from the relationships of multinational corporations with their foreign publics. How nation-states, countries, or societies manage their communicative relationships with their foreign publics remains largely in the domain of political science and international relations. (p. 138)

Public diplomacy is defined as “the way in which both government and private individuals and groups influence directly or indirectly those public attitudes and opinions which bear directly on another government’s foreign policy decisions” (Delaney, 1968, p. 3). Public diplomacy is a communicative struggle in “a global marketplace of ideas” (Signitzer & Coombs, 1992, p. 139) to create favorable and intended attitudes and opinions toward a nation. The objective of public diplomacy is “to influence the behavior of a foreign government by influencing the attitudes of its citizens” (Malone, 1988, p. 3).

Building and maintaining a positive national image enable a nation to achieve a more advantageous position in global economic and political competition. A positive national image may drive other nations’ foreign policies in favor of a country, increase revenues from trade, and draw tourists and foreign investment (Wang, 2006).

Cognizant of these benefits, many governments are active in practicing public relations to improve their national images throughout the world. Lee (2006) found that in 2002, more than 150 countries signed public relations contracts with agencies in the United States, based on his analysis of Foreign Agency Registration Act (FARA) data administered by the U.S. Department of Justice. He mentioned that “Asian countries were the most active in public relations in the U.S. followed by Western European and Middle East countries. Analyzing individual countries, Japan was ranked as the first, remotely followed by the UK, Mexico, Taiwan, South Korea, and Germany” (p. 99). He also found that building a relationship with the U.S. partners was the most frequent activity type of international public relations, followed by information dissemination, event promotion, advertising, and media relations. The major U.S. partners were governmental officials, Congress leaders, media owners, journalists, corporate leaders, and investors, who are generally considered opinion leaders in the United States.

The foreign news media have become a major target for governments trying to influence news content about international issues and foreign affairs, especially with regard to their own countries. However, governments also reach foreign publics directly by disseminating information about their countries and launching government-sponsored international broadcasting channels (e.g., Voice of America) and Web sites. Governments also try to influence public opinion in foreign countries through cultural exchange programs (e.g., artistic performances, film festivals, second-language training, and student exchange programs). The Fulbright program, which subsidizes international students’ education in the United States, is a good example of such efforts.

To effectively execute public relations programs overseas, many governments hire public relations firms in target countries. According to Gilboa (2000), contracting public relations firms in the target country is believed to be more effective than any other governmental strategy in international public relations in reaching and affecting both foreign publics and the foreign media because it can “strengthen the legitimacy and authenticity” of the public relations campaigns. In addition, geographic proximity of the resident PR firms operating in the target country enables quick reactions when a crisis related to the target country occurs.

Development communication (Newsom, Carrell, & Kruckeberg, 1993) and nation building (Taylor, 1998; Taylor & Botan, 1997; VanLeuven, 1996) share some aspects of international public relations. Taylor (2000) mentioned that “a public relations approach to nation building focuses on relationships between governments and publics as well as the creation of new relationships between previously unrelated publics” (pp. 183–184). The role of communication in nation building is determined by which “diverse societies, regions, and groups within a country are linked into a national-state system” (Morrison, 1989, p. 18). This approach is now extending its meaning from domestic nation building to international relationship building among nations.

Hosting the Olympic Games has been considered by many countries as an effective public diplomacy tool, through which the host country could promote a desired national identity and image among foreign publics (Kunczik, 2003). Considering the exceptional amount of attention they get from spectators all over the world, the Olympic Games provide a unique opportunity to appeal to foreign publics through maximum media exposure of the host country. For example, the 1988 Seoul Olympic Committee tried to change South Korea’s image from that of a war-stricken developing country to a prosperous country with economic success and advanced technology. More recently, China did the same by converting her negative image (e.g., that of a controlled communist country with human rights issues, lack of environmental protection, and poor quality of products) into a positive one by hosting the 2008 Beijing Olympics. China promoted the three themes of the Beijing Olympics: (1) green Olympics, which emphasizes China’s effort to improve environmental protection; (2) high-tech Olympics, which highlights China’s economic success and development accelerated by technological advancement; and (3) people’s Olympics, which puts “people” at the center of the Olympic spirit and sends messages to the outside world that China cares about human rights and tries to improve them (Berkowitz, Gjermano, Gomez, & Schafer, 2007). It must be an intriguing question whether the desired outcomes of the host country can really happen. Overall, many studies support “the Olympic effect” (Fishman, 2005; Spà, Rivenburgh, & Larson, 1995).

Culture and Public Relations

It seems generally agreed on that scholars and practitioners interested in international public relations need to look beyond their cultural biases and assumptions—the U.S.-centered understanding of public relations.

Zaharna (2001) suggested that international public relations scholars need to adopt more from the interaction and the processes of intercultural communication perspectives. Adaptation, negotiation, conflict management, and diplomacy are some of the ideas that should be applied to the study of international public relations. Zaharna’s in-awareness approach is focused on sensitivity to cultural differences. Zaharna sees public relations as defined by national parameters (country profile) and by cultural nuances (cultural profile), and then elaborated on with communication components. This approach emphasizes international public relations as a process of intercultural communication between client and practitioner. However, this approach needs to be extended because it is limited in scope to client-practitioner relationships, instead of to the bigger picture of organization-public relationships.

Kinzer and Bohn (1985) described two public relations models in multinational corporations—ethnocentric versus polycentric. The ethnocentric model (Illman, 1980) assumes that there is no difference between motivating people in domestic and in foreign countries. This model supposes that the people will respond similarly to the same message. This assumption leads to the idea that “what is known about public relations in the U.S. or the EU can be applied in less developed countries” (p. 151). In contrast, the polycentric model ensures more freedom of decision making by local public relations practitioners.

Strongly opposing the ethnocentric model of public relations, Botan (1992) argued that

what has been called international public relations may not actually be the two-way multicultural exercise that its name implies. The practice of public relations across borders often and maybe increasingly, is controlled and directed by the home country based on assumptions inherent to the home country. (pp. 151–152).

Basically, Botan criticized the fact that the majority of international public relations discourse is rooted in the management-oriented definition of international public relations based on Western ethnocentric assumptions.

Simoes (1992) questioned the concept of public relations in a communication and promotion function. Instead, he suggested a “political” function of public relations from a Latin American viewpoint. He claimed that the assumption guiding his view of public relations is conflict based on power relations. In Simoes’s view, relationships between organizations and publics create political dimensions to organizational decisions.

Banks (2000) introduced a socio-interpretive approach as a contribution to intercultural public relations. He suggested that public relations assumptions be flexible and adaptable to whatever the intercultural situation presented. He developed three principles of communication policy in international public relations by focusing on cultural interpretations and community building:

- Facts and values are culturally conditioned. Development is a Western concept with positive values in the West. But elsewhere, development often looks like exploitation and cultural imperialism.

- Knowing other cultures’ rituals, languages, social norms, and values is necessary but not sufficient preparation for forming international community relationships. It is necessary also to remain open to the possibility of conducting business within others’ worldviews and effectiveness criteria.

- The practitioner and researchers should be ready to redefine the nature of public relations situationally. We must leave open to interpretation and negotiation what constitutes the forms and goals of practice, depending on the cultural context. (p. 113)

Banks (2000) continued that

the global/local approach to managing international public relations should be modified to provide for interactivity through genuine dialogue. A first step is for practitioners and host nation officials to jointly create at the beginning of the relationship a public relations matrix for the host society, including its goals, plans, and projects. (p. 113)

A Case of Multicultural Setting

In 1995, there were more than 2,000 multinational companies located along the border between the United States and Mexico (McDaniel & Samovar, 1996). These companies are often called “maquiladoras”“labor-intensive foreignowned industries which assemble products for export to other countries” (Kras, 1995, p. xxi). Most maquiladoras are U.S.-owned, but many of the investors are from other countries, such as Japan, South Korea, Germany, and Canada. The two largest Mexican border citiesTijuana and Ciudad Juarezhave grown from small tourist towns into urban industrial centers within a very few years (Kras, 1995).

Samsung Tijuana Park is one of the many successful maquiladoras in Tijuana. This plant is part of Samsung Group, a large business conglomerate in South Korea. Samsung Tijuana Park was established in 1996, beginning as a manufacturing complex for electronic commodities and components for color television sets, VCRs, monitors, and tuners. There were 100 Korean managers and 6,500 Mexican workers in 2000. Between 1997 and 1999, the number of Mexican workers doubled, and by 1999, Samsung Tijuana Park ranked as the second largest maquiladora in Tijuana (Patta, 1999).

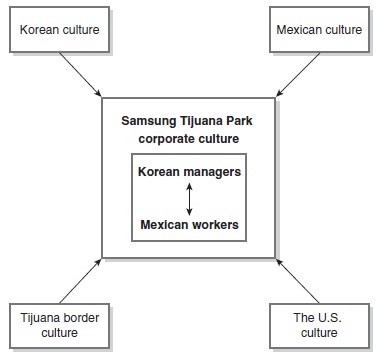

In multinational companies such as Samsung Tijuana Park, two or more cultural factors affect the organizational culture as a whole. Figure 1 shows the cultural environment in Samsung Tijuana Park. “Border culture” is treated as a unique culture because people in Tijuana are more Americanized than people in the other Mexican cities, given the area’s proximity to the United States. As a result of many people moving to Tijuana for jobs in maquiladoras, they experience contact with cultures different from their own.

Figure 1. Multicultural Setting in Samsung Tijuana Park

Without a doubt, the two national cultures represented by Korean managers and Mexican employees are the primary factors influencing Samsung Tijuana Park culture. In Samsung Tijuana Park, Korean managers and Mexican workers are cultural strangers to each other. Each cultural group within a multinational company has its own common pattern of cognitive, affective, and behavioral structures and processes. Because of this cultural gap, multinational companies may face challenges or “unintended conflicts” different from, and sometimes more serious than, those in their domestic settings. For example, there might be serious problems in training new employees and in cultural communication between managers and workers.

To measure perceptual similarities and differences between Korean managers and Mexican workers regarding various cultural dimensions such as individualismcollectivism, tolerance to uncertainty, and acceptance of power distance, Lee (2001) developed a new concept, “co-acculturation,” by synthesizing the co-orientation model and adaptation theory. Co-acculturation is defined as “simultaneous orientation toward each other and cultural dimensions” (p. 17). Co-acculturation is not one group’s acculturation to a host culture or the sum of each group’s acculturation. Rather, it represents “mutual acculturation” and “relational acculturation.” Based on a survey (N = 255), Lee found that (1) Mexican workers accurately perceive that they share power-distance values with their Korean managers, but the managers are generally less accurate in that they perceive greater differences than actually exist; (2) Mexican workers perceive that Koreans are as collectivistic as they are; however, Korean managers perceive that Mexicans are more individualistic than Korean managers; (3) Mexican workers perceive that Korean managers are more likely to avoid uncertainty at their job than they actually are; and (4) Korean managers perceive that Mexican workers are less likely to avoid uncertainty at their job than they actually are.

These misconceptions between cultural groups in multinational work settings may interfere with the integration of new workers and cause higher turnover. In this regard, the success or failure of a multinational company cannot be explained by economic factors alone. Effective intercultural communication and mutually beneficial relationship building between cultural groups, especially manager-worker relationships, serve as significant indicators of successful operation of multinational companies in the global economy.

From a public relations perspective, it is now commonplace for multinational organizations to include two or more cultures under a single corporate umbrella. Globalization makes work settings much more culturally heterogeneous. Not surprisingly, manager-worker communication presents new challenges for both those directly involved and those charged with building and maintaining relationships within the organization—the public relations staff. Old assumptions and communication skills are put to the test when public relations practitioners must build and maintain new organizational relationships with culturally different employees, government entities, communities, and customers.

Furthermore, cultural heterogeneity is not necessarily limited to national culture issues. It also can be extended to other subcultures. For example, in an organization under merger and acquisition, people from different corporate cultures typically confront each other. This confrontation may pose a serious threat to building a new organizational culture.

Concluding Comments

world means opportunities and challenges for practitioners as well as for scholars. The fact that public relations practitioners need to communicate with international publics has become a reality for both small and large organizations. As Grunig (1993) pointed out, “The growth of international media, global business and global politics has strengthened the role of international public relations” (p. 141). Multinational organizations are regarded as more vulnerable to hostile reactions or crises than domestic organizations because of the increased numbers and complexities of those stakeholders who oppose them and the necessity for dealing with their crosscultural contexts (Dilenschneider, 1992). International public relations “may be a necessary part of doing business for the public relations firms of the next century” (L. A. Grunig, 1992, p. 128). This promises to attract more attention and interest to this specific area of public relations and opportunities to build on the significant achievement previously attained.

Although educators are beginning to pay more attention to international public relations, there are only a few cases of international public relations classes being regularly offered in the university curriculum. Public relations educators need to find ways to expose students (future public relations professionals) to more of the various topics and issues related to international public relations because understanding public relations in this globalized world is not optional. It is must-have knowledge.

There is still a long way to go in building the body of knowledge about international public relations. What is missing in many previous studies titled global or international public relations is ironically the “global” or “international” aspect of public relations. It is clear that descriptive studies focusing on one individual country, without any overarching conceptualization, have limited value. Simply adding more and more isolated cases in multiple countries cannot lead to adequate explanatory knowledge on international public relations.

Bibliography:

- Banks, S. P. (2000). Multicultural public relations: A socialinterpretive approach (2nd ed.). Ames: Iowa State University Press.

- Berkowitz, P., Gjermano, G., Gomez, L., & Schafer, G. (2007). Brand China: Using the 2008 Olympic Games to enhance China’s image. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 3, 164–178.

- Botan, C. (1992). International public relations: Critique and reformulation. Public Relations Review, 18, 149–160.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., & Ingle, M. D. (1989). Between blueprint and process: A structured flexibility approach to development management. Public Administration and Development, 9, 487–503.

- Chay-Nemeth, C. (2001). Revisiting publics: A critical archaeology of publics in the Thai HIV/AIDS Issue. Journal of Public Relations Research, 13, 127–161.

- Culbertson, H. M., & Chen, N. (Eds.). (1996). International public relations: A comparative analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Curtin, P. A., & Gaither, T. K. (2007). International public relations: Negotiating culture, identity, and power. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cutlip, S. M., Center,A. H., & Broom, G. M. (2005). Effective public relations (9th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Delaney, R. F. (1968). Introduction. In A. S. Hoffman (Ed.), International communication and the new diplomacy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Dilenschneider, L. (1992). A briefing for leaders: Communication as the ultimate exercise of power. New York: HarperCollins.

- Fishman, T. C. (2005). China, Inc.: How the rise of the next superpower challenges America and the world. NewYork: Scribner.

- Gilboa, E. (2000). Mass communication and diplomacy: A theoretical framework. Communication Theory, 10, 275–309.

- Grunig, J. E. (1992). Generic and specific concepts of multicultural public relations. Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Policy, Research and Development in the Third World, Orlando, FL.

- Grunig, J. E. (1993). Public relations and international affairs: Effects, ethics, and responsibility. Journal of International Affairs, 47, 137–162.

- Grunig, J. E., Grunig, L. A., & Dozier, D. M. (2002). Excellent public relations and effective organizations: A study of communication management in three countries. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Grunig, J. E., Grunig, L. A., Sriramesh, K., Huang,Y., & Lyra, A. (1995). Model of public relations in an international setting. Journal of Public Relations Research, 7, 163–186.

- Grunig, L. A. (1992). Strategic public relations constituencies on a global scale. Public Relations Review, 18, 127–136.

- Grunig, L. A., Grunig, J. E., & Vercic, D. (1998). Are the IABC’s excellence principles generic? Comparing Slovenia and the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada. Journal of Communication Management, 2, 335–356.

- Heath, R. L. (2001). Handbook of public relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Illman, P. F. (1980). Developing overseas managers and managers overseas. New York: Amazon.

- Kinzer, H. J., & Bohn, E. (1985, June). Public relations challenges of multinational corporations. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Honolulu, HI.

- Kras, E. S. (1995). Management in two cultures: Bridging the gap between U.S. and Mexican managers. Yarmouth, MN: Intercultural Press.

- Kunczik, M. (1997). Images of nations and international public relations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Kunczik, M. (2003). Transnational public relations by foreign governments. In K. Sriramesh & D. Vercic (Eds.), The global public relations handbook: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 399–424). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lee, S. (2001). Co-acculturation in a multinational organization: A study of Samsung Tijuana Park at the U.S.-Mexico border. Unpublished master’s thesis, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA.

- Lee, S. (2006). An analysis of other countries’ international public relations in the U.S. Public Relations Review, 32, 97–103.

- Malone, G. D. (1988). Political advocacy and cultural communication: Organizing the nation’s public diplomacy. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- McDaniel, E. R., & Samovar, L.A. (1996). Cultural influences on communication in multinational organizations: The maquiladora. In L. A. Samovar & R. E. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural communication: A reader (pp. 289–296). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Morrison, D. G. (1989). Understanding black Africa: Data and analysis of social change and nation-building. New York: Irvington.

- Newsom, D., Carrell, B., & Kruckeberg, D. (1993). Development communication as a public relations campaign. Paper presented at the meeting of Association for the Advancement of Policy, Research, and Development in the Third World, Cairo, Egypt.

- Park, J. (2001). Images of “hong bo (public relations)” and PR in Korean newspapers. Public Relations Review, 27, 403–420.

- Patta, G. (1999, June 14). The largest maquiladoras in Tijuana. San Diego Business Journal, 200.

- Porter, R. E., & Samovar, L. A. (1996). An introduction to intercultural communication. In L. A. Samovar & R. E. Porter (Eds.), Intercultural communication: A reader (pp. 5–26). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Rhee,Y. (2002). Global public relations:A cross-cultural study of the excellence theory in South Korea. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14, 159–184.

- Signitzer, B. H., & Coombs, T. (1992). Public relations and public diplomacy: conceptual convergences. Public Relations Review, 18, 137–147.

- Simoes, R. P. (1992). Public relations as a political function: A Latin American view. Public Relations View, 18, 189–200.

- Spà, M. D. M., Rivenburgh, N. K., & Larson, J. F. (1995). Television in the Olympics. London: John Libbey.

- Sriramesh, K., Kim, Y., & Takasaki, M. (1999). Public relations in three Asian cultures: An analysis. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11, 271–292.

- Sriramesh, K., & Vercic, D. (2003). The global public relations handbook: Theory, research, and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Stohl, C. (2001). Globalizing organizational communication. In F. M. Jablin & L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The new handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods (pp. 323–375). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Taylor, M. (1998). Nation building as strategic communication management: An analysis of campaign planner intent in Malaysia. In L. Lederman (Ed.), Communication theory: A reader (pp. 287–293). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt.

- Taylor, M. (2000). Toward a public relations approach to nation building. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12, 179–210.

- Taylor, M., & Botan, C. H. (1997). Public relations campaigns for national development in the Pacific Rim: The case of public education in Malaysia. Australian Journal of Communication, 24, 115–130.

- VanLeuven, J. K. (1996). Public relations in Southeast Asia: From nation building campaigns to regional interdependency. In H. M. Culbertson & N. Chen (Eds.), International public relations: A comparative analysis (pp. 207–221). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Vasquez, G. M., & Taylor, M. (2001). Research perspectives on the public. In R. L. Heath (Ed.), Handbook of public relations (pp. 639–647). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Vercic, D., Grunig, L. A., & Grunig, J. E. (1996). Global and specific principles of public relations: Evidence from Slovenia. In H. M. Culbertson & N. Chen (Eds.), International public relations: A comparative analysis (pp. 31–65). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wakefield, R. I. (1996). Interdisciplinary theoretical foundations for international public relations. In H. M. Culbertson & N. Chen (Eds.), International public relations: A comparative analysis (pp. 17–30). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wakefield, R. I. (2000). Preliminary Delphi research on international public relations programming: Initial data supports application of certain generic/specific concepts. In D. Moss, D.Vercic, & G. Warnaby (Eds.), Perspectives on public relations research (pp. 179–208). London: Routledge.

- Wang, J. (2006). Managing national reputation and international relations in the global era: Public diplomacy revisited. Public Relations Review, 32, 91–96.

- Zaharna, R. S. (2001). In-awareness approach to international public relations. Public Relations Review, 27, 135–148.