View sample teaching processes in elementary and secondary education research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we know a great deal about the teaching processes that occur in classrooms, including the teaching processes that can improve achievement (e.g., Borko & Putnam, 1996; Brophy & Good, 1986; Calderhead, 1996; Cazden, 1986; Clark & Peterson, 1986; Doyle, 1986; Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986; Shuell, 1996). This research paper reviews the most important findings and emerging directions in the study of teaching in elementary and secondary schools.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Most work reviewed in the first section of this research paper was generated in quantitative research. Researchers spent a great deal of time observing in classrooms, looking for particular teaching behaviors and coding when they occurred. Often, these researchers also carried out analyses in which classroom teaching processes were correlated with achievement. Such observational and correlation work sometimes was complemented by experimentation to determine whether particular teaching processes could result in improved learning. The result of this work was a great deal of knowledge about naturalistically occurring teaching processes, including direct transmission and constructivist teaching processes.

In the second section, we take up an important part of teaching—motivating students. There has been a great deal of research focusing on stimulating student motivation through teaching, so as to increase academic efforts and accomplishments.

The third section covers teacher thinking about teaching. Such thinking presumably directs acts of teaching; hence, understanding teacher thinking is essential to understanding teaching.

The fourth section is about expert teaching; it summarizes what excellent teachers do as they teach well. Such teaching is exceptionally complicated. Excellent teachers masterfully orchestrate many of the most potent teaching approaches to create their expert teaching.

In the fifth section, we review the challenges teachers face. A realistic analysis of teaching processes must consider that when excellent teaching occurs, it happens largely because the teacher is a very good problem solver— very capable of negotiating the many demands on her or him.

Classroom Teaching Processes and Their Effects on Achievement

There was a great deal of research during the second half of the twentieth century about the nature of classroom teaching, what it is like, and when it is effective. Although many different teaching mechanisms were identified, two overarching approaches to teaching emerged—the direct transmission approach and constructivist teaching.

Direct Transmission Approach

One of the most famous analyses of classroom teaching processes was conducted by Mehan (1979), who observed that much of teaching involves a teacher’s initiating a question, waiting for a student response, and then evaluating the response—what Mehan referred to as IRE cycles (i.e., initiate-respond-evaluate cycles). A hefty dose of such interactions reduces the teacher’s classroom management burden (Cazden, 1988, chap. 3) because students know what is required of them during such cycles given their frequent involvement in them. The teacher can go through a lesson in an orderly fashion, covering what she or he considers to be essential points. Given that many teachers view their jobs as covering so much content, days and days of such interactions make much sense to many teachers (Alvermann & Hayes, 1989; Alvermann, O’Brien, & Dillon, 1990). Such teaching, however, has many downsides; one is that lower-level and literal questions are more likely than higher-level questions. Moreover, this approach to teaching and learning is very passive, with the discussions often boring and only one student at a time interacting with the teacher (Bowers & Flinders, 1990, chap. 5; Cazden, 1988, chap. 3); this is direct transmission teaching, in which the teacher decides what will be discussed and learned.

Mehan (1979) documented that direct transmission of information in school is more the norm than the exception. Much of teaching involves a teacher’s explaining, demonstrating, and asking questions. The explanations and demonstrations tend to come first, followed by the teacher-led IREs, sometimes followed by more teacher explanation and demonstration if students struggle with the content. Such direct instruction of information is defensible in that there is substantial evidence that direct transmission of information from teachers to students produces student learning (Brophy & Good, 1986; Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986).

Collapsing across the process-product studies (i.e., investigations correlating teaching process differences with variations in student achievement), the following conclusions about effective direct instruction emerged (see Brophy & Good, 1986, for a review, with many of the conclusions that follow generated by those authors; also see Rosenshine & Stevens, 1986):

- In general, the more academically focused the classroom, the greater the learning—that is, the greater the proportion of class time spent on academics, the greater the learning. The less time spent on low-level management of the class (e.g., checking attendance, discipline), the greater the learning.Thetasksassignedshouldneitherbetoohard,nor too easy, but rather challenging enough to require the students to engage in them—challenging enough so that effort produces success. The more time the teacher directly teaches, the greater the learning.

- Achievement increases to the extent that teachers structure learning. This can be done through provision of advance organizers, outlines, and summaries.

- Practicing newly-taught skills to the point of mastery, with the teacher providing support as needed, improves achievement.

- Teacher questioning improves student learning (Redfield & Rousseau, 1981). It helps when the teacher’s questions are clear and when the teacher permits the student time to formulate answers (i.e., the teacher uses wait time). Questioning as part of guided practice permits the teacher to check understanding of concepts being practiced (e.g., a math skill). Such checking of understanding promotes student learning.

- Feedback improves achievement—that is, it helps students to know when they are correct. Praise should make clear what the student did well, providing information about the value of the student’s accomplishment. It should emphasize that the student’s success was due to effort expended (Brophy, 1981).

- Seatwork and homework should be engaging rather than busywork. The teacher should monitor whether and how well such work was completed.

- Having students work together cooperatively during seatwork usually improves achievement.

- Regular review of material improves achievement.

The direct transmission approach focuses on teaching behaviors—teacher explanations, questioning, feedback to students, and assignments. The more teacher behaviors stimulate students to attend to things academic—especially things academic that are within the student’s grasp (i.e., neither too easy nor too difficult)—the greater the achievement is; positive associations have been found between direct teaching behaviors and student achievement, with a great strength of the direct transmission approach being an impressive database of support.

Constructivist Teaching

In contrast to direct transmission is the constructivist approach to teaching and learning. An extreme version is discovery learning (Ausubel, 1961; Wittrock, 1966), which entails placing children in environments and situations that are rich in discovery opportunities—that is, rather than explaining to students what they should do, they are left to discover both what to do and how to do it, consistent with theories such as Piaget’s that assert learning is best and most complete (i.e., understanding is most certain) when children discover concepts for themselves (Brainerd, 1978; Piaget, 1970). Teacher input often boils down to answering questions that students might pose as they attempt to do a task.

To be certain, students sometimes can make powerful discoveries, for instance, of strategies during problem solving (e.g., Groen & Resnick, 1977; Svenson & Hedonborg, 1979; Woods, Resnick, & Groen, 1975). That said, many times students fail when left to discover how to carry out an academic task. Worse is that sometimes they make errant discoveries; for example, they may discover weak strategies for solving a problem or strategies that are just plain wrong (Shulman & Keislar, 1966; Wittrock, 1966)! For example, when students are left to discover how to subtract on their own, there are hundreds of errant approaches that they can and do invent (Valheln, 1990).

Short of pure discovery, however, is guided discovery, which involves the teacher posing questions to students as they attempt a task. The questions are intended to lead students to notice ways that a task could be approached—that is, the questions provide hints about the concepts the child is to discover, but the child has to make substantial effort to figure out the situation compared to when a teacher directly teaches how to do a task. In recent years, such guided discovery teaching has come to be known as scaffolding (Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976)—Like the scaffolding of a building, the teacher provides support when needed, with the scaffolding reduced as the child’s mind, which is under construction, is increasingly able to handle the task. The teacher provides enoughsupport(hintsandprompts)forthechildtocontinueto make progress understanding a situation but does not provide the student with answers or complete explanations about how to find answers. Such guided discovery takes more time than more direct teaching, however. Moreover, it requires teachers who know the concepts being taught so well that they can make up questions in response to student attempts and errors as they attempt tasks (Collins & Stevens, 1982).

Many science educators favor guided discovery. Tobin and Fraser (1990) documented that effective constructivist science teachers monitor their students well as they attempt academic tasks, quickly intervening with questions and prompts when students get off task. Excellent constructivist science teachers continue lessons until they are certain their students understand what is being taught. The goal of constructivist teaching is student understanding, not simply the student’s getting through the task or getting a correct answer. Constructivist science educators require students to explain their thinking, and they work with students until the students do understand. In good science classes, all students are required to be active, for example, attempting to generate a solution to a problem and discuss alternative problem solutions with one another (Champagne & Bunce, 1991)— that is, students do not discover alone but work together to discover (e.g., doing chemistry or math problems together). Students learn how to think together (e.g., Newman, Griffin, & Cole, 1989), which mirrors much of the problem solving that occurs in the real world (e.g., problem solving by committees, which is the typical approach to many important problems in adult life).

Although guided discovery more certainly leads to learning than pure discovery, there is a cost. The students do explore less than they do during pure discovery. They tend to wait for teacher’s guiding questions and prompts rather than explore the problem or topic on their own (Hogan, Nastasi, & Pressley, 1999). Even so, when students in Hogan et al.’s (1999) study were left on their own to solve a science problem through group discovery, they joked around more and often were distracted compared to when a teacher scaffolded their interactions; this finding is consistent with similar observations in other studies of students in discovery learning situations (e.g., Basili & Sanford, 1991; Bennett & Dunne, 1991; Roth & Roychoudhury, 1992). Bickering also is common during pure discovery and student small-group problem solving (e.g., Nastasi, Braunhardt, Young, & MargianoLyons, 1993). Frequently, only a subset of the students do most of the work and thinking during such interactions (e.g., Basili & Sanford, 1991; Gayford, 1989; Richmond & Striley, 1996). Communications between discovering learners are often unclear; conclusions are incomplete and sometimes illogical (e.g., Bennett & Dunne, 1991; Eichinger, Anderson, Palincsar, & David, 1991). Despite the problems with discovery and guided discovery approaches, supporters of these approaches are adamant that it is good for children’s cognitive development to struggle to discover (e.g., Ferreiro, 1985; Petitto, 1985; Pontecorvo & Zucchermaglio, 1990) because conceptual disagreements between students can lead to much hard thinking by the students.

The case in favor of guided discovery has grown stronger in recent years, with many demonstrations that good teachers can scaffold students as they work on difficult academic tasks (Hogan & Pressley, 1997b), including learning to recognize words (e.g., Gaskins et al., 1997), use comprehension strategiestounderstandtexts(e.g.,Pressley,El-Dinary,etal.,1992), solve math problems (e.g., Lepper, Drake, & O’Donnell-Johnson, 1997), and figure out scientific concepts (Hogan & Pressley, 1997a). Student errors can be revealing about what students do not understand and be used by a teacher to shape questions and comments that cause students to think hard about misconceptions and sometimes come to better conceptions.

Direct Transmission Versus Constructivist Approaches to Teaching

Kohlberg and Mayer (1972) starkly contrasted direct transmission and constructivist views of instruction. Both require teachers to do more than do methods favored by romantic views of development and schooling inspired by Rousseau’s (1979) Emile. Rousseau made the case there that education at its best left the child alone to explore the world. Perhaps the most famous school in modern times conceptualized along such romantic lines was A. S. Neill’s (1960) Summerhill. Learning proved to be anything but certain at Summerhill, however (Hart, 1970; Hemmings, 1973; Popenoe, 1970; Snitzer, 1964). It is notable that there have been no serious, large-scale attempts to implement romantic education since Summerhill—reflecting (at least in part) an awareness growing out of that experience that, when Mother Nature is left in charge, children’s intellectual development is not as certainly upward as Rousseau proposed.

Kohlberg and Mayer (1972) were very critical of transmission approaches, focusing on the behavioral underpinnings, which did not put any value on understanding—only on observable performances. Kohlberg and Mayer, who adopted a Piagetian perspective, believed that the centerpiece of education should put the child in situations that are just a bit perplexing to the child and just a bit beyond the child’s current understanding. Hence, the child who has single-digit subtraction mastered is ready to try double-digit subtraction. The good teacher provides such a child with some doubledigit subtraction problems and perhaps hints about how double-digit subtraction is like single-digit subtraction but does not teach the child how to do double-digit subtraction in a step-by-step fashion.

Constructivist-oriented educators in the Kohlberg tradition were particularly interested in how to increase students’ ability to reason about difficult social and moral problems. Their hypothesis was that letting children discuss such problems to come up with solutions was the route to cognitive growth. During such discussions, many challenges would stimulate the participants to think hard about social and moral dilemma situations, with the result that students would develop and internalize more sophisticated reasoning skills. The teacher should play the role of one of the participants in the conversation, gently nudging the participants to think about some possibilities not yet offered in the conversation (e.g., What about——?). In fact, when students have opportunities to participate in such discussions about moral dilemmas, their social and moral reasoning skills do improve—consistent with Kohlberg’s theory—although the effects are more pronounced among secondary than among elementary students (Enright, Lapsley, & Levy, 1983).

Since Kohlberg and Mayer (1972), the direct transmission versus constructivist debate has played out many times in American education. For example, in recent years, there has been a huge debate about how to teach beginning reading—one side favors direct instruction of word recognition competencies (i.e., phonics), and the other favors an approach known as whole language, which includes learning to recognize words through discovery as children experience great children’s literature and write their own compositions (Pressley, 1998). Consistent with how those favoring direct transmission have made their case in the past, those favoring direct teaching of reading have amassed a great deal of scientific evidence that direct teaching of phonics and related skills produces more certain word recognition than less direct teaching. The National Reading Panel (2000) report was particularly systematic in reviewing all of the evidence favoring such a direct instruction perspective. Consistent with traditional constructivist arguments, whole language proponents feel that direct teaching of word recognition does not result in a complete understanding of reading; they have produced an impressive array of evidence that children’s understandings are more developed in whole language contexts (e.g., Dahl & Freppon, 1995; Graham & Harris, 1994; Morrow, 1990, 1991; Neuman & Roskos, 1990). For example, experiences with literature increase children’s understanding of the structure of stories (e.g., Feitelson, Kita, & Goldstein, 1986; Morrow, 1992; Rosenhouse, Feitelson, Kita, & Goldstein, 1997). Children’s comprehension of ideas expressed in text increase when they have conversations about literature with peers and teachers (Van den Branden, 2000).

Direct Transmission and Constructivism

Kohlberg and Mayer (1972) believed that if students were taught, they could not then discover. Another possibility, however, does exist. Kohlberg and Mayer (1972) are correct in their assertion that when a teacher teaches directly (i.e., explains a concept), understanding is incomplete. Even so, understanding is complete enough so that the student can at least begin to apply the new knowledge or use the new skill that was just explained. To do so correctly, however, might require some help from the teacher (i.e., scaffolding), with understanding of the new idea or procedure increasing as the student, in fact, does use it—that is, by attempting to use what has been taught directly, the learner constructs a much more complete understanding. That direct transmission and constructivism are not completely incompatible has stimulated new thinking about how teaching can be done better.

For example, what has emerged in the beginning reading debate is a middle position calling for instructional balance of direct teaching of skills and whole language experiences (i.e., reading of literature, composition; see Pressley, 1998). Advocates for balanced literacy instruction make the reasonable assumptions that learning how to sound out words is more certain if taught directly and that reading of real literature provides especially rich practice of word recognition. Writing also provides much opportunity to explore and experiment with words, with the knowledge of letter-sound combinations tried out and stretched in many ways as children try to figure out how to spell the words they want to put in their stories.

That direct transmission and constructivist literacy experiences can be coordinated was documented explicitly by Pressley, El-Dinary, et al. (1992) in their work on the teaching of comprehension strategies to elementary students. The teachers they studied first explained and modeled a small repertoire of comprehension strategies to their students, including predicting based on prior knowledge, asking questions during reading, constructing mental images during reading, seeking clarification when confused, and summarizing. Then, over a long period of time, the teachers scaffolded students’ use of the strategies as they read in small reading groups. Brown, Pressley, Van Meter, and Schuder (1996) demonstrated that a year of such scaffolded practice at the second-grade level resulted in more active reading and greater comprehension of what was read. Collins (1991) and Anderson and Roit (1993) produced comparable outcomes in the later elementary grades and at the middle school level, respectively.

Learning of comprehension strategies as conceived by Pressley, El-Dinary, et al. (1992) was highly constructivist (Harris & Pressley, 1991; Pressley, Harris, & Marks, 1992). The students did not apply the strategies mechanically; rather, they worked at flexibly adjusting the strategies relative to the demands of reading tasks. Students discussed among themselves their strategy attempts and alternative understandings of texts (e.g., how their summaries of a text differed). Teachers did not direct students to use particular strategies as they read text, but rather provided general prompts to be active and to experiment (e.g., What might you do if you’re not sure you understand?). They also encouraged students to use what they were learning during reading in class across the day (e.g., When you are reading for social studies, try some of the strategies.).

As we offer these examples from reading that represent a balancing of direct instruction and constructivist experiences, we are also reminded that direct transmission versus constructivist battles continue to be fought. Aprominent one is in mathematics education, with the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2000) arguing strongly for constructivist mathematics teaching and many traditionalists favoring direct teaching of skills (e.g., Dixon, Carnine, Lee, Wallin, & Chard, 1998).

Summary

Although both direct instruction and constructivist advocates can point to research supporting their favored teaching mechanisms, the alternative that enjoys increasing support is instruction that involves both direct transmission and constructivist elements. The invention of such teaching does inspire some extreme advocates both of direct instruction and of constructivist teaching to assert their positions even more adamantly, resulting in conflicting and sometimes confusing advice presented to teachers. Such recommendations must be sorted out in the teacher’s own mind, which was one motivation for researchers interested in teaching processes to study teacher thinking.

Motivational Processes

During the last quarter century there has been a revolution in thinking about how academic learning and achievement can be motivated in classrooms. There are now a number of specific motivating, instructional approaches that are defensible based on well-regarded educational research.

Rewarding Achievement

The behaviorists contended that to increase behavior, one should reward (reinforce) it. It is not quite that simple! If the behavior is one that the student does not like or is not doing, then providing reward for performing the behavior (or for performing the behavior well) is defensible. Alternatively, however, if it is a behavior that a student likes already (i.e., a behavior the student finds intrinsically rewarding), then providing an explicit reward can actually undermine the student’s future motivation to do this activity (Lepper & Hoddell, 1989). This phenomenon is called the overjustification effect (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973): There is a natural tendency when a person is rewarded for doing something to explain one’s behavior as being caused by the reward. As an example, consider a child who really loves reading and reads plenty of books just for the fun of it. Suppose one day the teacher adds the explicit reward of a pizza certificate for reading so many books, an incentive system used in many schools. As long as the pizza certificates keep coming, the situation is fine; alas, however, in the spring, when the pizza certificates stop as the incentives program winds down, reading might actually decline: The child stops reading because she or he now believes that reading was occurring because of the reward for reading.

One common form of reward in classrooms is praise, which can be very effective. Praise works best when it is given contingent on desirable student behaviors, when the teacher makes clear what was praiseworthy, when the praise is sincere, when there is an implication that the student can be similarly successful in the future by exerting appropriate effort, and when the praise conveys the message that the student seemed to enjoy the task or value the competencies gained from the exertion of effort (Brophy, 1981).

Encourage Moderate Risk Taking

Many students fear failure and hence are afraid to take risks. Good teachers encourage such students to be reasonable risk takers. Such risk taking, however, often produces increased achievement (see Clifford, 1991). Why? Consider writing as an example. Students have no chance to improve their writing skills if they refuse to try to write, fearing that their efforts will be unsuccessful; improvement can occur only after students try to write.

Emphasizing Improvement Over Doing Better Than Others

Most American classrooms emphasize performance—in particular, doing better than other students on academic tasks. Only a few students receive As relative to most students, who are much less successful. Such an approach undermines the motivation of all students (Ames, 1984; Nicholls, 1989), however. Those who do not receive As feel as if they failed relative to the A students. If the A students could do better than they are doing, they have no incentive to do so, for they are already earning the top grade that is available.

There is an alternative to emphasizing competitive grades—to praise students for improving from where they are now rather than for performing better than do other students. Classrooms that emphasize improvement, in fact, are more likely to keep students interested in and committed to school (Nicholls, 1989; Nicholls & Thorkildsen, 1987).

Cooperative Learning

Beyond downplaying competition, students can be encouraged to cooperate with one another, with reliably positive effects on achievement. Students often learn more when they work together (e.g., Johnson & Johnson, 1975, 1979, 1985). The most motivating situation is one in which students actually receive reward based on how well their fellow group members perform, creating great incentive for students to work together to make certain that everyone in the cooperative group is making progress (Fantuzzo, King, & Heller, 1992; Slavin, 1985a, 1985b).

Cognitive Conflict

Providing students with tasks that are just a little bit beyond them or a little different from what they already know is very motivating. Thus, if a student has the single-digit addition facts down (e.g., 5 2 7), single-digit subtraction problems might be intriguing and just a bit confusing. Thus, presenting a flash card with 5 2 3 might give the student motivation to pause to figure out why the answer is not 7, raising curiosity about that and what that dash might signify. Similar curiosity would not be expected in a child who did not know the addition facts already, for there would be no reason for such a child to think that 5 2 3 is a little strange. A variety of Piagetian-inspired educators (see Kohlberg, 1969) have made the case that students’ curiosity can be stimulated by presenting new content that is just a little bit different from what the students already know.

Making Academic Tasks Interesting

People pay more attention to content that is interesting—a good reason to present students with content that will grab them (e.g., Hidi, 1990; Renninger, 1990; Renninger & Wozniak, 1985). That said, sometimes material grabs student attention but distracts from what is really important. For example, juicy anecdotes in a history piece can reduce the attention paid to the main points of the article (e.g., stories about Kennedy playing touch football with the family on the White House lawn can be remembered better than can the accomplishments of the Kennedy administration, which were the main focus; e.g., Garner, 1992). Similarly, educational computer games are often loaded with distractions that succeed in orienting student attention to lights and bells rather than to the content that the program is intended to teach (e.g., Lepper & Malone, 1987). On a more positive note, reading can be made more fun by having the students read books that they find interesting. Similarly, social studies and science content can be illustrated by examples that students find intriguing rather than boring—examples that illustrate well important points made in the text.

Encouraging Effort Attributions

Students can attribute successes and failures they have experienced to a number of factors. Unfortunately, most of these attributions are to factors out of their control. Thus, explaining one’s success as due to high ability or one’s failure to low ability is tantamount to attributing outcomes to something the student cannot control. Luck is also out of the student’s control, so that to attribute a success to good luck or a failure to bad luck is to conclude that one’s educational fates are not under personal control. Finally, explaining good and bad grades as due to easy and difficult tests is the same as believing that educational success is all in the hands of the test makers. Explaining successes and failures in terms of such uncontrollable factors undermines motivation. If success in school depends on ability, luck, or test difficulty, then there is no incentive to try because successes and failures will occur unpredictably.

Alternatively, students can explain their educational outcomes in terms of the one factor they can control—their effort. Explaining successes as reflecting hard work—and failures as due to not enough work—wields positive motivational power. The message is that doing well depends on personal effort, which the student can decide to expend. Encouraging students to make effort attributions increases their motivation to learn new skills that are taught (e.g., Carr & Borkowski, 1989).

Emphasizing the Changeable Nature of Intelligence

A related point is that students can believe their academic intelligence is fixed and out of their control, with this belief undermining motivation to work hard in school. Alternatively, students can believe their intelligence is modifiable— that by learning more, people really became smarter (e.g., Henderson & Dweck, 1990). In fact, when classrooms emphasize that school is about mastering what is being taught there and such mastery produces intellectual empowerment, achievement is greater (e.g., Ames, 1990; Ames & Archer, 1988; Nicholls, 1989).

Increasing Student Self-Efficacy

People with positive academic self-efficacy believe they can do academic tasks; academic self-efficacy is often quite specific (e.g., believing that one can achieve in mathematics—or more specific still, believing one can do even difficult word problems; Bandura, 1977, 1986). High self-efficacy motivates future effort (e.g., a student who perceives she or he can do math is more likely to try hard in math; Schunk, 1989, 1990, 1991). Self-efficacy is largely a product of success in a domain (e.g., success in mathematics produces math selfefficacy). Hence, it is important that students be successful in school and that assignments provide some challenge but not so much as to overwhelm.

Encouraging Healthy Possible Selves

It is academically motivating for a child to believe that she or he could go to college and eventually become a wellrespected, well-rewarded professional. Such students have healthy possible selves, which motivates them to work hard in school as part of a long-term plan that will get them to a productive role in the world (Markus & Nurius, 1986). Many children do not have such understandings or such positive possible selves, believing that higher education is something that could never happen to them and that they could never achieve valued roles in society. For children who do not have healthy possible selves, it makes sense to encourage more positive views about possible long-range futures. For example, Day, Borkowski, Dietmeyer, Howsepian, and Saenz (1994) were able to shift the expectations of Mexican American children upward through participation in discussions emphasizing how education can result in desirable jobs.

Discussion

Educational researchers have identified many specific approaches to motivate academic effort and achievement. One reading of this section is that these mechanisms are in competition with one another—that there are so many of them that it would be impossible to carry them all out. Jere Brophy (1986, 1987), however, proposed just the opposite—that trying to do it all with respect to motivation is exactly the way to produce more motivating classrooms and more motivated students. Brophy urged teachers to model interest in learning and communicate to students high enthusiasm for what is going on in school and that what is being learned in school is important. Brophy urged keeping achievement anxiety low and emphasizing learning and improvement rather than outdoing other students. Teachers should induce curiosity and suspense, make abstract material more concrete, make learning objectives salient, and provide much informative feedback. According to Brophy, teachers also should adapt tasks to students’ interest, offer students choices whenever possible, and encourage student autonomy and self-reliance. Learning by doing should be encouraged; tasks that produce a product are especially appealing (e.g., class-produced big books). Games should be part of learning. The case is made later in this research paper that Brophy’s perspective that teachers should try to do much to motivate is enjoying support in the most recent research on classroom motivation, with exceptionally engaging teachers doing much to motivate their students—that is, excellent teachers know much about how to motivate their students, and they use what they know.

Teachers’ Knowledge, Beliefs, and Thinking

The cognitive revolution heightened awareness that teachers actively think as they teach and that what they know and believe about teaching very much affects the classroom decisions they make. During the last two decades of the twentieth century, there were substantial analyses of what teachers know and believe (see Borko & Putnam, 1996; Calderhead, 1996; Carter & Doyle, 1996; Clark & Peterson, 1986; Reynolds, 1989; Richardson, 1996); what follows in this section is an amalgamation of conclusions from these previous reviews of the evidence.

Teachers think before they teach (i.e., they plan for the year, this unit, this week, what will be covered today, and what will be covered in this lesson; Clark & Yinger, 1979), and they think as teaching proceeds (e.g., they react to student needs). Teachers also can think after they teach, reflecting on what went on in their classroom, the effects of their teaching, and how their teaching might be improved in the future. All of this thinking is informed and affected by various types of knowledge possessed by teachers: Teachers know how to teach, having learned classroom management strategies, instructional strategies, motivational techniques, and a variety of theories of learning. They have beliefs about themselves as teachers. They have subject matter knowledge, including knowledge about how particular subjects can be taught (i.e., pedagogical content knowledge; Shulman, 1986).

With respect to every type of knowledge that teachers can possess, there are individual differences between teachers in what they know and believe. For example, some teachers know more than do others about cognitive strategies instruction. Among those knowledgeable about cognitive strategies, some believe that strategies should be taught directly, whereas others think that students should be helped to discover powerful strategies but not be told explicitly how to carry them out. Some teachers even know about strategies instruction but choose not to teach strategies because they do not believe that reading comprehension really is a consciously strategic process (e.g., Pressley & El-Dinary, 1997). Teacher beliefs can powerfully affect teaching, including beliefs about self as teacher (e.g., I’m not good at teaching math.), the nature of students (e.g., They don’t want to learn. The students do not have much prior knowledge that can be related to science lessons.), effective classroom management (e.g., Students should be seen and not heard. A good teacher is clearly in charge of the classroom. In a good classroom, students are self-regulating.), and the nature of effective teaching and learning (e.g., Teachers should be coaches more than dictators. Students learn best through direct instruction. Students learn best when given opportunities to construct their own knowledge.).

A teacher’s knowledge is acquired over a long period of time, with some of it reflecting information garnered from experiencing kindergarten through college education as a student. Some was conveyed formally in courses in college—for example, education methods courses. Other knowledge was acquired on the job as a function of gaining experience in the classroom, observing other teachers, and experiencing professional development provided to teachers in the field. Teachers’ practical knowledge of schools dramatically shifts with experience. Only through actually teaching in a working school can subtle knowledge of the teaching craft be acquired. Formal knowledge of teaching, however, can transform as teachers attempt to use modern conceptions of teaching and learning compared to conceptions of teaching and learning that predominated when they were taught. Thus, knowledge of writing can change as a function of experience as a writing workshop teacher of composition. The shift can be from a focus on writing as mastery of mechanics (which was the emphasis during schooling for many who are now teachers) to writing as a process of planning, drafting, and revising (which is the current focus of most curricular thinking about composition), with concerns about mechanics most prominent as the composition product is being polished. Knowledge of and beliefs about mathematics instruction can change when a school district decides to move away from curricula emphasizing procedural learning to curricula emphasizing student construction of mathematical understandings and real-world problem solving. To become an expert professional takes a while (5–10 years; e.g., Ericsson, Krampe, & Tesch-Römer, 1993)—both to learn how to teach and to believe one can teach well—despite the fact that while they are in teacher education programs, many are very confident (probably overconfident) that they will be good teachers (e.g., Book & Freeman, 1986; Weinstein, 1988, 1989).

Expert Teaching

That teachers have much to learn themselves has stimulated much hard thinking about what experienced teachers know and need to know—especially what really good teachers know and believe. By analyzing the thinking and teaching of experienced and skilled teachers, an understanding of teaching at its best is emerging. A possible reading of the research summarized briefly in this section is that a teacher can possess many bits and pieces of knowledge that can mediate discrete teaching events. The research reviewed in the next section goes far in emphasizing that real teachers, however, connect their knowledge and their practices to create entire lessons, school days, content units, and years.

Cognitive psychologists have carried out many expertnovice comparisons, especially focusing on the thinking of experts compared to novices as they do important tasks (e.g., reading X rays, flying planes; e.g., Lesgold et al., 1988). Experts think about problems in a way very different from that of novices. Experts quickly size up a situation as roughly like others they have seen—that is, they have well-developed schemas in their domain of expertise (e.g., expert radiologists know what metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung looks like, and this knowledge is quickly activated when they confront a specific X ray having some of the features of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the lung). After a candidate schema is generated, the expert then carefully searches for information confirming or disconfirming the schema (e.g., noticing whether the many tumors in this X ray of the lung are more round than spiculated, which would be consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma; noticing whether there is a metastatic path from the primary tumor). The novice might not be so thorough and thus might rush to a conclusion (e.g., concluding quickly that the many tumors in the lung field must be adenocarcinoma, perhaps even explaining away the spiculated look of the tumors as due to the poor fidelity of X rays). Also, unlike the novice, the expert radiologist is not going to be distracted by irrelevancies (e.g., looking at sections of the X ray that do not contain telling information). Cognitive psychologists interested in expert-novice differences in cognition consistently were able to demonstrate that experts had better developed schematic knowledge in their domains of expertise; this knowledge was used more systematically and completely by experts compared to novices to accomplish tasks in the domain of expertise.

The most prominent expert-novice work done in the field of teaching was carried out by David Berliner and his associates (e.g., Berliner, 1986, 1988; Carter, Cushing, Sabers, Stein, & Berliner, 1988; Carter, Sabers, Cushing, Pinnegar, & Berliner, 1987). They studied both teachers identified by their schools as expert teachers and early-career teachers. For example, Sabers, Cushing, and Berliner (1991) had teachers watch a videotaped lesson, with the wide-screen image capturing everything that was happening in the room. The teachers were asked to talk aloud as they watched what was happening; the researchers also posed some specific questions about what was happening in the classroom, probing teachers’understanding of the classroom routines, the content being covered, motivational mechanisms being used by the teacher, and interactions between students and teachers.

The main result was that the expert teachers saw the room much differently from the way the novices saw it. Basically, the experts made better interpretations of what they saw and were more likely to recognize well-developed routines, to identify classroom structures the teacher had put in place, and to detect student interest and boredom. The experts also took in more of the room rather than overfocusing on one part to the exclusion of another. The experts listened more to what the students said, whereas the novice teachers were more likely to focus on the visual clues alone. Berliner and his associates concluded that expert teachers have well-developed knowledge of classroom schemas: They know what particular routines look like (e.g., entering the room and getting to work immediately), the important approaches to curriculum and instruction (e.g., a hands-on science activity), and prototypical ways in which students and teachers can interact (e.g., cooperative learning); this knowledge base permits them to interpret what can seem to be many disjointed activities to novices who lack such knowledge. Thus, novices are likely to focus onthemanyspecificbehaviors in a hands-on science activity rather than simply recognize it as a unified activity. Such schemas allow much more complete comprehension and memory of what is going on in a classroom (e.g., Peterson & Comeaux, 1987).

A criticism of these studies is that expert teaching is not just about teacher thinking. In fact, it is mostly about actual teaching, which was not captured at all in the expert-novice studies focusing on teacher cognition. In a series of studies conducted with our associates (Bogner, Raphael, & Pressley, 2002; Pressley, Allington, Wharton-McDonald, Block, & Morrow, 2001; Pressley, Wharton-McDonald, et al., 2001; Wharton-McDonald, Pressley, & Hampston, 1998), we captured the many ways in which the teaching of excellent elementary teachers differs from the teaching of more typical and weaker elementary teachers. In each of these studies, we identified teachers who were very engaging (i.e., most of their students were academically engaged most of the time) and those who were less engaging (i.e., students were often off task, or the tasks they were doing were not academically oriented).As we anticipated, when engagement was high, there were also indications of better achievement (i.e., students wrote longer, more coherent, and generally more impressive compositions; studentsreadmoreadvancedbooks;studentsperformedbetter on achievement tests than students in classrooms where engagement was lower). This work was more decidedly qualitative and intended to develop a theory of effective elementary teaching rather than quantitatively hypothetico-deductive (see Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The theory that emerged was that excellent teachers do much well: (a) They develop a motivating classroom atmosphere, (b) classroom management is superb, and (c) their curriculum and instructional decisions sum to excellent teaching for all students.

A Motivating Classroom Atmosphere

Effective elementary teachers create a motivating classroom environment. Excellent teachers have both the physical environment and the psychological input to the students aligned to promote engagement and learning.

Physical Environment

The teacher has constructed a comfortable and inviting place for learning, with many educational materials readily accessible for students. For example, there are reading corners filled with great books, listening stations with tapes of favorite stories, and math labs with concrete manipulatives (e.g., play money, counting blocks) that appeal to students. Charts and maps that can support teaching and learning are hung so that they can be used during teaching and referenced easily by students. The classroom is decorated with fun and attractive items (e.g., brightly colored signs, posters that are appealing to the eye). Some of the decorations are studentproduced work. The displays change frequently as the seasons change, new topics are covered in class, and students produce new products that can be showcased. Posters reflect some of the psychological virtues the teacher espouses for the classroom (e.g., exerting effort, making good choices, high expectations), making salient the interconnections between the physical and psychological classroom worlds.

Psychological Environment

Excellent teachers promote community in their classroom and it shows—beginning with their communications (e.g., our class, we work together). The teacher makes frequent connections to students, mentioning in passing a student’s achievement, alluding to the birth of a sibling, and expressing empathy to a child who has a reason to feel blue (e.g., a grandparent is ill)—that is, excellent teachers send the message that they are interested in students’ lives, which are valuable. The teacher’s communications are filled with respect for students, and the students’ communications mirror that respect—for example, with many please and thank-you comments. Teachers remind students often about the virtues of being helpful, respectful, and truthful with one another. Excellent teachers have gentle, caring manners in the classroom, with positive interactions in abundance. The teacher is often playful with the kids (e.g., actually playing with them during recess, kidding around with them as they work). Excellent teachers typically have good senses of humor—for example, laughing at themselves when they make a mistake solving an arithmetic problem. Good teachers model inclusion and embrace diversity by including all of the children in the class and celebrating openly the various traditions and backgrounds represented by students (e.g., celebrating with genuine enthusiasm Columbus Day, St. Patrick’s Day, and Martin Luther King Day). Cooperation is encouraged (e.g., much cooperative learning), as is altruism (students helping other students, making valentines for people in nursing homes, collecting soda cans to donate the proceeds to an adopted family in Guatemala).

The classroom is also a democratic place. There are serious discussions between students and teachers about classroom issues (e.g., how disobedience should be handled, how the needs of individuals can be balanced against the needs of the entire class). Sometimes these discussions take up matters of power and inequity (e.g., how kids don’t always get the respect they deserve). Good teachers reduce such inequalities by permitting the students to make up classroom rules and to be involved in decision making (e.g., what novel to read next). When students disagree, respectful disagreement is encouraged and compromises are sought (e.g., if the vote between two novels is split, it might be resolved by a coin flip, with the decision to read the losing novel after the winning novel is completed).

The teacher does much to create an interesting classroom. He or she arouses curiosity (e.g., Listen carefully. You’ll find out some of the answers to the questions we’ve been asking. or Go ahead and open our new book—see anything interesting?). The good teacher creates anticipation (e.g., Tomorrow, I’m going to teach you how I figure out those percentages on tests, which will be cool.).

Excellent teachers create classrooms emphasizing effort. The teacher lets students know that they can do the assigned tasks if they try, also making clear that the way smart people became smart was by trying hard and thus learning much. Good teachers send the message that school tasks deserve attention and serious effort and that much good comes from doing and reflecting on school work. When students have difficulties, the teacher encourages stick-to-itiveness, letting the students know that they can succeed by persevering. The teacher does not attribute either student successes or failures to luck, ability, or task difficulty—factors out of the students’ control.The teacher downplays competition, emphasizing not who is doing better than others in the class but that students are improving.The teacher encourages effort in many ways— for example, often remarking Who can tell me? Who remembers? Make your best guess if you are not sure.

Excellent teachers create classrooms downplaying performance outcomes—that is, the teacher does not make salient who is doing well and who is not. Grades are not made publicly (e.g., by calling grades in or putting papers with the best grades on display). The teacher does not criticize student mistakes. There are no academic games with obvious losers (e.g., a spelling bee) but rather academic games in which everyone wins often (e.g., social studies Jeopardy in which students are made to feel they are winners when they get the answer in their heads).

Excellent teachers foster self-regulation. They give their students choice in their work (e.g., allowing students to select which books they will read). Students in excellent elementary classrooms are expected to move from task to task on their own rather than wait for teacher direction. Students are encouraged to set their own goals (e.g., how many books to read in a month). The teacher honors student ownership of their own work and control of it (e.g., Would you mind if other children look at what you wrote?). In short, the teacher wants students to be in charge of themselves.

The excellent teacher publicly values learning. The teacher frequently makes remarks about the value of education, using the mind, and achieving dreams through academic pursuits. The teacher is enthusiastic about academic pursuits, such as reading books and writing. The excellent teacher does not emphasize extrinsic rewards (e.g., stickers) for doing things academic but rather focuses on the intrinsic rewards (e.g., the excitement felt when one is reading a particular novel, the sense of accomplishment accompanying effective writing).

The excellent teacher also has high expectations about students, communicating frequently to students that they can learn at a high level (e.g., Wow, third graders, this is stuff usually covered in fifth grade, and you are doing great with it.). Moreover, excellent teachers are determined that students in their charge will learn. Even so, excellent teachers have realistic ambitions and goals for their students, encouraging their students to try tasks they can accomplish—ones that with effort are within their reach.

Excellent teachers create classrooms filled with helpful feedback—especially praising students when they do well and trying to do so immediately. Teachers do not give blanket praise, but rather are very explicit in their praise (e.g., I really like this story—it is a page longer than your last story, with much better spelling and punctuation and a great ending.).

In summary, excellent teachers go to great lengths to create a generally motivating classroom atmosphere. In fact, the classroom day is saturated with teacher actions that motivate. For example, Bogner et al. (2002) studied 7 first-grade teachers and found that two were much more motivating than were the others in the sample (e.g., their students were much more engaged in academic activities than were students in other classes). One of these two teachers used 43 different motivational mechanisms to encourage her students over the course of the school day, with many of these mechanisms used multiple times; the other used 47 different approaches— again, with many repeated multiple times. In both classrooms, the motivational attempts were always positively toned and never punitive or critical of students. In contrast, much more criticism and far fewer approaches to motivating students were observed in the other five classrooms.

Dolezal, Mohan, and Pressley (2002) conducted a similar study at the third-grade level. Their most engaging teacher used 45 different motivating mechanisms over the course of the school day, compared to far fewer motivational mechanisms in other third-grade classrooms, in which students were much less engaged. Excellent teachers create classroom environments that are massively motivating: It is impossible to be in their rooms for even a few minutes without several explicit teacher actions intended to motivate student engagement and learning.

Effective Classroom Management

The classroom management of effective teachers is so good that observers hardly notice it—there is little misbehavior in the classroom and rarely a noticeable disciplinary event. This result is due in part to a classroom management strategy that has at its core the development of self-regulated students.

Self-Regulation Routines

Effective teachers make clear from early in the year how students in the class are supposed to act. The teacher communicates to students that is important for them to learn and carry out the classroom routines and act responsibly. There are routines for many daily classroom tasks (e.g., a hot lunch counter can on the teacher’s desk, with students depositing their token counter in the can)—tasks that can consume much time in ordinary classrooms (i.e., the lunch counter can eliminate the need for the teacher to do lunch count during the morning meeting). An especially important routine is for students to learn that they are to keep on working even if the teacher is not available; the internalization of this routine is obvious in effective classrooms because it does not matter whether the teacher is in the room—everyone works regardless of the teacher’s absence. Early in the year, excellent teachers teach their students how to work cooperatively, and for the rest of the year, cooperative learning is the norm. In short, just as excellent teachers have high academic expectations of students, they also have high behavioral expectations.

Explanations and Rationales

Excellent teachers do not simply pronounce rules. Rather, they explain why the classroom community has the rules and regulations that are in place. Explanations are also given as the teacher makes important decisions (e.g., why the class is going to the library tomorrow rather than today, why the class is reading the current story and how it connects with the current social studies unit). The message is clear that the classroom is a reasonable world rather than an arbitrary one.

Monitoring

Excellent teachers monitor their classes and show high awareness of what everyone is doing. Excellent teachers act quickly when students experience frustrations or are getting off task (e.g., asking a student with wandering attention what he or she is doing and what he or she should be doing). When excellent teachers detect potential disruptions, they respond quickly and efficiently to eliminate such disruptions (e.g., giving paper towels to a student who just spilled, helping the student so that the spill is cleaned up quietly).

Discipline

There are few discipline events; the teacher does not have to use discipline or disciplinary threats to keep students on task. In fact, excellent teachers do not threaten their students. If punishment is necessary, it is done quietly and in a way that gets the student back on task very quickly. Thus, excellent teachers never send students to a time-out corner; rather, they swiftly move to correct the behavior and get the student back to the work assigned at the place where the work should be performed (e.g., whispering to the student We’ll talk at recess.).

Excellent Use of Other Adults

Excellent teachers use parent volunteers and classroom aides well.Basically, these adults interact with the children much like the teacher: They provide support as needed, always in a positive way. Such good use happens because excellent teachers coach volunteers and aids well, making certain they know what to do to be consistent with the ongoing philosophy, instruction, and curriculum in the classroom. Excellent teachers often use such adults to provide additional help to weaker students—for example, listening to weaker readers read or helping weaker arithmetic students with challenging problems. (Often, during our visits, parents and aides told us how excellent the teacher was, reflecting that good teachers inspire great confidence in the other adults who work in their classrooms!)

In summary, excellent teachers orchestrate everyone in their classroom well—through persuasion rather than coercion. They are continuously aware of the state of their classroom and the students in it, and they do what is required to keep students engaged and productive. Their management style is consistent with the generally positive atmosphere in the classroom, with few reasons for punishment and few punishments dispensed.

Curriculum and Instruction

Excellent teachers make curriculum and instruction decisions that result in exciting teaching and interesting lessons. Students learn content that is exciting; the lessons are presented in interesting ways that match their abilities to deal with it.

Engaging Content and Activities

The books that are read and the lessons that are taught are interesting to the students, with the teacher consciously selecting materials that will intrigue the class (e.g., because it worked well last year). There are many demonstrations that make abstract content more concrete and do so in ways that connect academic content to the child’s world and larger life (e.g., a lesson on biological adaptations that protect a species includes exploring the parts of a rose plant and reflecting on why it has thorns)—that is, students learn by doing. When new content is covered, the teacher highlights for students how it connects to ideas covered previously in the class (e.g., when an information book is read about how the colors of bears are matched to their habitats, the teacher reminds students about the previous lesson on biological adaptations). Such opportunities to connect across lessons are not accidental; the teacher plans extensively—both individual lessons and the sequence of lessons across the year.

Lessons do not merely scratch the surface; rather, the teacher explanations and class discussions have some depth. In general, depth is favored over breadth in excellent classrooms.

Play and games are incorporated into instruction. Thus, the class might play social studies Jeopardy to review for an upcoming test or math baseball. The emphasis in these games is decidedly on the content, however—the teacher takes advantage of misses to provide reinstruction (i.e., the misses inform the teacher about ideas that need additional coverage and reexplanation).

The students make products as part of instruction. Thus, it is common in very good primary classrooms to see big books on display that the class has written and produced. A science unit on plants can result in a small forest in the corner of the room. A sex education unit can include a class-made incubator in which chicks are hatched by the end of the lessons. Such products are a source of pride for students and do much to motivate their interest in what is going on in the classroom.

The message is salient that what goes on in school has clear relevance to the world. One way this occurs is through use of current events to stimulate classroom activities. Hence, a presidential election can be used to stimulate literacy and social studies activities related to the presidency. Space shuttle launches can be prime motivation for thinking about topics in astronomy, exploration, or technology. The annual dogsled races in Alaska can be used to heighten interest in the study of Alaska, the character issue of perseverance, or use of the Internet (i.e., the race can be followed on the Internet, which has many resources about the race available for students to explore).

There is no doubt that interest is high in classrooms staffed by excellent teachers. One indicator is that students are all doing activities connected to lessons (e.g., self-selecting library books related to current content coverage). Another is that the students are excited about any possibility of doing more or participating more extensively (e.g., student hands are always up to volunteer; students will stay in at recess to finish composition of a big book or help distribute the concrete manipulatives for the next activity). When a student is asked about what she or he is doing the student will often give a long and enthusiastic response. The teacher’s selection of interesting and exciting content goes far in creating an interesting and exciting classroom.

Instructional Density

Excellent teachers are constantly teaching and providing instruction. Whole-group, small-group, and individual minilessons intermingle across the day, and the teacher often takes advantage of teachable moments (e.g., moments that provide the opportunity to teach), such as when students pose questions. The teachers sometimes prompt students how to find answers themselves and sometimes use the question as an opportunity to provide an in-depth explanation. Students also do much reading and writing because excellent teachers do not permit students simply to sit and do nothing. Excellent teachers teach in multiple ways—explaining, demonstrating, and scaffolding student learning. Teacher-led lessons and activities are sometimes complemented by film or Internet experiences. Although many lessons involve multiple activities, the academically demanding parts of the lesson get the most time and attention. For example, if students write in response to a reading, they might be asked to illustrate what they wrote. The illustration activity will never be the focus; rather, the teacher makes it clear that the illustrating comes after reading and writing and should be accomplished quickly. The dense articulation of instruction and activities in excellent classrooms requires great teacher organization and planning.

Balanced Instruction

Rather than embracing instructional extremes, excellent teachers use a range of methods. Admittedly, because the focus of our work is primary-level education, we know more about this issue with respect to literacy. Engaging teachers clearly balance skills instruction and holistic reading and writing experiences, rather than embracing either a skills-first or whole language approach exclusively.

Excellent teachers are not dependent on worksheets or workbooks; they favor much more authentic tasks, such as reading real books, writing letters that will be mailed, and composing stories that end up in big books on display in the classroom. Moreover, the real books that the students read are great books—Newberry Award winners and enduring classics—great stories that are well told and that inspire the students. Such books are read aloud, read in small groups, and then reread by students to one another and by students with their parents at home. Practicing a book until it can be read to proficiency is more successful when the books being read and reread are so very appealing. Moreover, students never just read one book at a time; typically, they are reading several. Good books contain important vocabulary, which the teacher covers before reading.

The excellent illustrations in good books provide much to be seen and talked about by students—for example, when the teacher does a picture walk through a book before reading it. Part of instruction is that the teacher always encourages students to read books that are a little bit challenging—ones that can be grasped with effort. Much of reading instruction is such matching of students to books, providing students with opportunities to learn to read by doing reading.

Writing provides opportunity to teach higher-order composing skills (i.e., planning, drafting, and revising as a recursive cycle) as well as lower-order skills (e.g., mechanics and grammar). Writing also reinforces reading skills. Thus, just as students are encouraged to stretch words to sound them out during reading, they are encouraged to stretch them to spell them during writing. Instructional activities in excellent classrooms provide complementary learning experiences and orderly articulation of experiences, rather than a jumbled mix of disconnected experiences that never comes together.

Cross-Curricular Connections

Reading, writing, and content learning often connect in excellent classrooms. Thus, science and social studies lessons require reading and writing in response to what is read and experienced as part of content lessons. In general, excellent teachers do much to make connections across the curriculum. Often, they accomplish this task by emphasizing a particular theme for a week or so (e.g., a social studies unit about the post office in which students read books about the post office or read books in which postal letters play a prominent role, with the reading and social studies lessons complemented by the writing of postal letters). Connections occur across the entire year of instruction in excellent classrooms; the teachers remind students of how ideas encountered in today’s lesson connect to ideas in previous lessons (e.g., during a story about polar bears, the teacher reminds students about the unit earlier in the year about animal biological adaptations). Connections, of course, do not stop at the classroom door. For example, the excellent teacher makes certain that students know about books in the library connecting with current instructional themes and is effective in getting students interested in such books.

Thinking Processes

Excellent teachers send the message that students can learn to think better, explicitly teaching the students problem-solving processes and strategies for a variety of academic tasks. The excellent teacher encourages students to reflect critically about ideas and to be creative in their thinking. As part of stimulating their students’thinking, excellent teachers model problem-solving skills, often thinking aloud as they do so. For example, when writing directions on the board, the excellent teacher might reread what was written, asking aloud whether it makes sense or whether there might be some errors that could be corrected. Similarly, when reading a passage aloud, the teacher might model rereading in order to understand the passage better. Perhaps when confronting a new vocabulary word in a text, the teacher might sound out the word for the students.

Provides Appropriate Challenges

Excellent teachers appropriately challenge their students, consistently presenting content that is not already known by their students but not so advanced that students cannot understand it even if they exert effort. For example, elementary classrooms often have many leveled books, with students encouraged to read books at a level slightly beyond their current one. Also, when excellent teachers ask questions during lessons, they are difficult enough to require some thinking by students but not so difficult that there are only a few bidders to answer them.The pace of questioning—and the pace of all instruction—is not so slow as to bore students. During questionand-answer sessions and all of instruction, excellent teachers encourage risk taking (e.g., encouraging students to give their answers to a question even if the expressions on their faces suggest that they are not certain about it).

Different students get challenged in different ways in good classrooms: Excellent teachers embrace the diversity of talents and abilities in their classes. The need to personalize challenges often means that one-on-one teaching is required, with the teacher monitoring carefully what the student can handle and then providing input well matched to the student.

Scaffolding

Excellent teachers scaffold student learning, providing just enough support so that students can continue to make progress with learning tasks and withdrawing help as students can do tasks autonomously.As part of scaffolding, excellent teachers ask questions as students attempt tasks—questions that can be revealing about what students know and do not know. Scaffolding also includes hints to students to check work, especially when the teacher detects shortcomings in student work (e.g., encouraging students to reread their own writing to detect potential problems). Scaffolding also involves urging students to help one another—for example, by encouraging students to read their compositions in progress to others in order to obtain suggestions about how to continue the writing. Scaffolding teachers also encourage students to apply the problem solving, reading, and writing strategies that have been taught in class (e.g., prompting use of the word wall to find some of the words they want to include in their stories).

Monitoring

Excellent teachers walk around their classrooms a great deal, monitoring how their students are doing and asking questions to check for understanding. As they do so, excellent teachers note who needs additional help and which ideas should be covered additionally with the whole class.

Clear Presentations

Excellent teachers give clear directions, which are easy to follow. The expectations are always clear for students as are the learning objectives.

Home-School Connections

Excellent teachers communicate to parents their expectations about parental involvement in student learning (e.g., reading with their children, helping with homework rather than doing it). Such teachers also ask students to have parents assist them with test preparation and sign selected assignments. Excellent teachers make certain through conferences, newsletters, and take-home assignment folders that parents know what is happening in class as well as what their students know and what help they need in order to achieve at higher levels.

Summary

What we have found in our work is that excellent teachers do much to make certain that the curriculum and instruction in their classrooms is excellent. Many different approaches to instruction are used, and many resources are organized to support student learning (e.g., classroom aides, students helping students, parental involvement with homework). The teacher models and encourages active thinking, not only with respect to today’s lesson but also in connecting the ideas encountered today with those encountered earlier in the year. The content and teaching challenge students but do not overwhelm them, which requires much planning because students are at different levels of ability. Although excellent teachers encourage student self-regulation, they always provide a safety net of support when students falter—teacher scaffolding, reinstruction, and reexplanations are prominent in excellent classrooms.

Discussion

Our work has been qualitative—intended to generate hypotheses about excellent teaching. The megahypothesis emerging from this work is that excellent teachers do not do simply one or a few things differently from more typical teachers. Rather, their teaching is massively different. They do much to motivate students. Their classroom management is masterful. Their classroom instruction is complex and coherent, meeting the needs of the whole class while matching to the abilities and interests of individual students.

This hypothesis contrasts with the perspectives of many educational researchers. Those who claim that achievement is largely a function of motivation are like blind persons touching part of the elephant.Those who argue that classroom management is the key to classroom success are similarly blind, similarly touching only a different part of the elephant. Those who contend that one particular type of instruction or curriculum material will do the trick with respect to improving classroom functioning join the ranks of the blind persons from this perspective, simply tugging at yet another section of the elephant. The elephants that are excellent classrooms, however, are complex, articulated animals, with many parts spun together by their teacher leaders. The resulting elephant coherently walks and proceeds through a long life (i.e., forany particular cohort of students, usually at least a school year with the same teacher).The hypothesis we have generated is that to understand the elephants that are classrooms, it is necessary to understand the parts as well as the functioning whole, aware that masterful teachers develop classroom elephants with every individual part better—and every part articulating better—than do less masterful teachers who develop less impressive classroom elephants. That is to say, as anyone who has visited a zoo knows, although all elephants are complex creatures, some are more magnificent than others. We love watching the most magnificent of these beasts when we visit the zoo, preferring them to their less imposing cage mates, just as we love watching the classrooms created by excellent teachers much more than we love watching the classrooms created by more typical teachers down the hall.

Challenges of Teaching

Teaching is a challenging activity. Thus, beginning teachers are challenged during their first year or two of teaching (Veenman, 1984); analyses of beginning teaching challenges appear throughout the twentieth century, from Dewey (1913) to U.S. Department of Education reports at the end of the century (Lewis et al., 1999). There were many studies in between (Barr & Rudisell, 1930; Broadbent & Cruickshank, 1965; Dropkin & Taylor, 1963; Hermanowicz, 1966; Johnson & Ryan, 1980; Lambert, 1956; Lortie, 1975; Martin, 1991; Olson & Osborne, 1991; Ryan, 1974; Thompson, 1991; Wey, 1951). Although the challenges seem to decrease with experience, teaching remains a very challenging profession even for veterans (Adams, Hutchinson, & Martray, 1980; Dunn, 1972; Echternacht, 1981; Koontz, 1963; Lieter, 1995; Litt & Turk, 1985; Olander & Farrell, 1970; Pharr, 1974; Rudd & Wiseman, 1962; Thomas & Kiley, 1994). A complete analysis of teaching processes appreciates that teaching always occurs amidst contextual challenges.

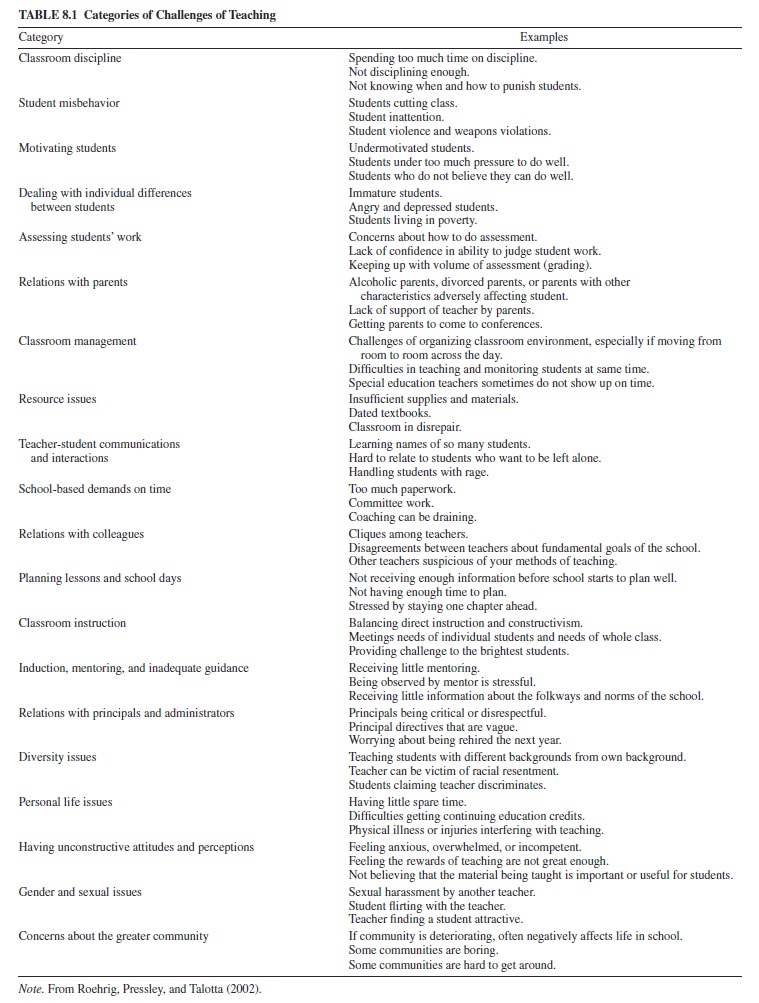

Roehrig, Pressley, and Talotta (2002) summarized all of the types of challenges that elementary and secondary teachers can face. Their starting point was the many published case studies of beginning teaching (e.g., Dollase, 1992; Kane, 1991; Kowalski, Weaver, & Henson, 1994; Ryan et al., 1980; Shapiro, 1993). Then they had a sample of first-year teachers and experienced teachers indicate which of the potential challenges occurred in their school lives during the past school year. The result was nearly 500 separate challenges, all of which were reported as experienced by one or more teachers. The challenges clustered into 22 categories, summarized in Table 8.1.

Some challenges are caused by characteristics of teachers themselves—by what they do not know (e.g., curriculum, rules of the school), teacher attitudes (e.g., not liking teaching), or physical illness. Some are caused by the students (e.g., their diversity, individual differences in abilities). Some are caused by the many responsibilities of the job (e.g., curriculum planner, disciplinarian, assessor). Some are caused by other adults in the school (e.g., other teachers, administrators, parents). Furthermore, there are the challenges outside the school (e.g., the teacher’s family or lack of family, challenges of inner city life). In short, challenges are coming from many directions.

That said, for both beginning and experienced teachers, Roehrig et al. (2002) found that the most frequent source of challenge that teachers report is the students—student misbehavior, lack of motivation, and individual differences were rated as frequent sources of challenge. There are many different types of student folks, all of whom need different strokes.