View sample social conflict and integration research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Humans are fundamentally social animals. Not only is group living of obvious contemporary importance (see Spears, Oakes, Ellemers, & Haslam, 1997), but also it represents the fundamental survival strategy that has likely characterized the human species from the beginning (see Simpson & Kenrick, 1997). The ways in which people understand their group membership thus play a critical role in social conflict and harmony and in intergroup integration. This research paper examines psychological perspectives on intergroup relations and their implications for reducing bias and conflict and for enhancing social integration. First, we review social psychological theories on the nature of individual and collective identities and their relation to social harmony and conflict.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Then, we examine theoretical perspectives on reducing intergroup bias and promoting social harmony. Next, we explore the importance of considering majority and minority perspectives on intergroup relations, social conflict, and integration. The paper concludes by considering future directions and practical implications.

Individualand Collective Identity

Perspectives on social conflict, harmony, and integration have reflected a variety of disciplinary orientations. For instance, psychological theories of intergroup attitudes have commonly emphasized the role of the individual, in terms of personality and attitude, in social biases and discrimination (see Duckitt, 1992; Jones, 1997). Traditional psychological theories, such as the work on the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950), have considered the role of dysfunctional processes in the overt expression of social biases. More contemporary approaches to race relations, such as aversive racism and symbolic racism perspectives, have considered the contributions of normal processes (e.g., socialization and social cognition) to the expression of subtle, and often unconscious, biases (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1998; S. Gaertner & Dovidio, 1986; Kovel, 1970; Sears, 1988; Sears & Henry, 2000). In addition, the role of social norms and standards is emphasized in recent reconceptualizations of older measures, such as authoritarianism. Right-wing authoritarianism (Altemeyer, 1996, 1998) has been found to be associated with negative attitudes toward a number of groups, particularly those socially stigmatized by society (e.g., Altemeyer, 1996; Esses, Haddock,& Zanna, 1993).

Recent approaches to intergroup relations within psychology have also considered the role of individual differences in representations of group hierarchy. Social dominance theory (Pratto & Lemieux, 2001; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994; see also Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) assumes that people who are strongly identified with high-status groups and who see intergroup relations in terms of group competition will be especially prejudiced and discriminatory toward out-groups.These biases occur spontaneously as a function of individual differences in social dominance orientation, in contexts in which in-group–out-group distinctions are salient (Pratto & Shih, 2000). Scales developed to measure social dominance orientation pit the values of group dominance and equality against each other (see Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). People high in social dominance orientation believe that group hierarchies are inevitable and desirable, and they may thus see the world as involving competition between groups for resources. They endorse items such as, “Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups” and “Sometimes other groups must be kept in their place.” Individuals high in social dominance orientation believe that unequal social outcomes and social hierarchies are appropriate and therefore support an unequal distribution of resources among groups in ways that usually benefit their own group (see Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius, Levin, & Pratto, 1996). Individuals low in social dominance orientation, in contrast, are generally concerned about the welfare of others and are empathic and tolerant of other individuals and groups (Pratto et al., 1994). They tend to endorse items such as, “Group equality should be our ideal” and “We would have fewer problems if we treated people more equally.”

Sociological theories, in contrast, have frequently emphasized the role of large-scale social and structural dynamics in intergroup relations in general and in race relations in particular (Blauner, 1972; Bonacich, 1972; Wilson, 1978). These theories have considered the dynamics of race relations largely in economic and class-based terms—and often to the exclusion of individual influences (see Bobo, 1999).

Despite the existence of such divergent views, both sociological and psychological approaches have converged to recognize the importance of understanding the impact of group functions and collective identities on race relations (see Bobo, 1999). In terms of group functions, Blumer (1958a, 1958b, 1965a, 1965b), for instance, offered a sociologically based approach focusing on defense of group position, in which group competition and threat were considered fundamental processes in the development and maintenance of social biases. With respect to race relations, Blumer (1958a) wrote, “Race prejudice is a defensive reaction to such challenging of the sense of group position. . . . As such, race prejudice is a protective device. It functions, however shortsightedly, to preserve the integrity and position of the dominant group” (p. 5). From a psychological orientation, Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, and Sherif (1961) similarly proposed that the functional relations between groups are critical in determining intergroup attitudes. According to this position, competition between groups produces prejudice and discrimination, whereas intergroup interdependence and cooperative interaction that result in successful outcomes reduce intergroup bias (see also Bobo, 1988; Bobo & Hutchings, 1996; Campbell, 1965; Sherif, 1966).

With respect to the importance of collective identity, psychological research has emphasized how the salience of group versus individual identity can influence the way in which people process social information. In particular, the operation of group-level processes has been hypothesized to be dynamically distinct from the influence of individual-level processes. Different modes of functioning are involved, and these modes critically influence how people perceive others and experience their own sense of identity. In terms of perceptions of others, for example, Brewer (1988) proposed a dual process model of impression formation (see also the continuum model; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; see also Fiske, Lin, & Neuberg, 1999). The primary distinction in Brewer’s model is between two types of processing: person based and category based. Person-based processing is bottom up and data driven, involving the piecemeal acquisition of information that begins “at the most concrete level and stops at the lowest level of abstraction required by the prevailing processing objectives” (Brewer, 1988, p. 6). Category-based processing, in contrast, proceeds from global to specific; it is top-down. In top-down processing, how the external reality is perceived and experienced is influenced by category-based, subjective impressions. According to Brewer, category-based processing is more likely to occur than is person-based processing because social information is typically organized around social categories.

With respect to one’s sense of identity, social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and self-categorization theory (Turner, 1985; see also Onorato & Turner, 2001) view the distinction between personal identity and social identity as a critical one (see Spears, 2001). When personal identity is salient, a person’s individual needs, standards, beliefs, and motives primarily determine behavior. In contrast, when social identity is salient, “people come to perceive themselves as more interchangeable exemplars of a social category than as unique personalities defined by their individual differences from others” (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987, p. 50). Under these conditions, collective needs, goals, and standards are primary.

This perspective also proposes that a person defines or categorizes the self along a continuum that ranges at one extreme from the self as a separate individual with personal motives, goals, and achievements to the self as the embodiment of a social collective or group.At the individual level, one’s personal welfare and goals are most salient and important.At the group level, the goals and achievements of the group are merged with one’s own (see Brown & Turner, 1981), and the group’s welfare is paramount. At each extreme, self-interest fully is represented by the pronouns “I” and“We,” respectively. Intergroup relations begin when people think about themselves as group members rather than solely as distinct individuals.

Illustrating the dynamics of this distinction, Verkuyten and Hagendoorn (1998) found that when individual identity was primed, individual differences in authoritarianism were the major predictor of the prejudice of Dutch students toward Turkish migrants. In contrast, when social identity (i.e., national identity) was made salient, in-group stereotypes and standards primarily predicted prejudiced attitudes. Thus, whether personal or collective identity is more salient critically shapes how a person perceives, interprets, evaluates, and responds to situations and to others (Kawakami & Dion, 1993, 1995).

Although the categorization process may place the person at either extreme of the continuum from personal identity to social identity, people often seek an intermediate point to balance their need to be different from others and their need to belong and share a sense of similarity to others (Brewer, 1991). This balance enhances one’s feelings of connection to the group and increases group cohesiveness and social harmony (Hogg, 1996). However, social categorization into in-groups and out-groups also lays the foundation for the development of intergroup bias or ethnocentrism. In addition, intergroup relations tend to be less positive than interpersonal relations. Insko, Schopler, and their colleagues have demonstrated a fundamental individual-group discontinuity effect in which groups are greedier and less trustworthy than individuals (Insko et al., 2001; Schopler & Insko, 1992). As a consequence, relations between groups tend to be more competitive and less cooperative than those between individuals. In general, then, the social cate gorization of others and oneself plays a significant role in prejudice and discrimination.

Although social categorization generally leads to intergroup bias, the nature of that bias—whether it is based on ingroup favoritism or extends to derogation and negative treatment of the out-group—depends on a number of factors, such as whether the structural relations between groups and associated social norms foster and justify hostility or contempt (Mummendey & Otten, 2001; Otten & Mummendey, 2000). However, different treatment of in-group versus out-group members, whether rooted in favoritism for one group or derogation of another, can lead to different expectations, perceptions, and behavior toward in-group versus out-group members that can ultimately create a self-fulfilling prophecy. Initial in-group favoritism can also provide a foundation for embracing more negative intergroup feelings and beliefs that result from intrapersonal, cultural, economic, and political factors. In the next section we describe alternative, and ultimately complementary, theoretical approaches to intergroup conflict and integration.

Perspectives on Intergroup Relations and Conflict

In general, research on social conflict, harmony, and integration has adopted one of two perspectives, one with an emphasis on the functional relations between groups and the other on the role of collective identities.

Functional Relations Between Groups

Theories based on functional relations often point to competition and consequent perceived threat as a fundamental cause of intergroup prejudice and conflict. Realistic group conflict theory (Campbell, 1965; Sherif, 1966), for example, posits that perceived group competition for resources produces efforts to reduce the access of other groups to the resources.This process was illustrated in classic work by Muzafer Sherif and his colleagues (Sherif et al., 1961). In 1954 Sherif and his colleagues conducted a field study on intergroup conflict in an area adjacent to Robbers Cave State Park in Oklahoma. In this study 22 12-year-old boys attending summer camp were randomly assigned to two groups (who subsequently named themselves Eagles and Rattlers). Over a period of weeks they became aware of the other group’s existence, engaged in a series of competitive activities that generated overt intergroup conflict, and ultimately participated in a series of cooperative activities designed to ameliorate conflict and bias.

To permit time for group formation (e.g., norms and a leadership structure), the two groups were kept completely apart for one week. During the second week the investigators introduced competitive relations between the groups in the form of repeated competitive athletic activities centering around tug-of-war, baseball, and touch football, with the winning group receiving prizes. As expected, the introduction of competitive activities generated derogatory stereotypes and conflict among these groups. These boys, however, did not simply show in-group favoritism as we frequently see in laboratory studies. Rather, there was genuine hostility between these groups. Each group conducted raids on the other’s cabins that resulted in the destruction and theft of property. The boys carried sticks, baseball bats, and socks filled with rocks as potential weapons. Fistfights broke out between members of the groups, and food and garbage fights erupted in the dinning hall. In addition, group members regularly exchanged verbal insults (e.g., “ladies first”) and name-calling (e.g., “sissies,” “stinkers,” “pigs,” “bums,” “cheaters,” and “communists”).

During the third week, Sherif and his colleagues arranged intergroup contact under neutral, noncompetitive conditions. These interventions did not calm the ferocity of the exchanges, however. Mere intergroup contact was not sufficient to change the nature of the relations between the groups. Only after the investigators altered the functional relations between the groups by introducing a series of superordinate goals—ones that could not be achieved without the full cooperation of both groups and which were successfully achieved—did the relations between the two groups become more harmonious.

Sherif et al. (1961) proposed that functional relations between groups are critical in determining intergroup attitudes. When groups are competitively interdependent, the interplay between the actions of each group results in positive outcomes for one group and negative outcomes for the other. Thus, in the attempt to obtain favorable outcomes for themselves, the actions of the members of each group are also realistically perceived to be calculated to frustrate the goals of the other group. Therefore, a win-lose, zero-sum competitive relation between groups can initiate mutually negative feelings and stereotypes toward the members of the other group. In contrast, a cooperatively interdependent relation between members of different groups can reduce bias (Worchel, 1986).

Functional relations do not have to involve explicit competition with members of other groups to generate biases. In the absence of any direct evidence, people typically presume that members of other groups are competitive and will hinder the attainment of one’s goals (Fiske & Ruscher, 1993). Moreover, feelings of interdependence on members of one’s own group may be sufficient to produce bias. Rabbie’s behavioral interaction model (see Rabbie & Lodewijkx, 1996; Rabbie & Schot, 1990; cf. Bourhis, Turner, & Gagnon, 1997), for example, argues that either intragroup cooperation or intergroup competition can stimulate intergroup bias. Similarly, L. Gaertner and Insko (2000), who unconfounded the effects of categorization and outcome dependence, demonstrated that dependence on in-group members could independently generate intergroup bias among men. Perhaps as a consequence of feelings of outcome dependence, allowing opportunities for greater interaction among in-group members increases intergroup bias (L. Gaertner & Schopler, 1998), whereas increasing interaction between members of different groups (S. Gaertner et al., 1999) or even the anticipation of future interaction with other groups (Insko et al., 2001) decreases intergroup bias.

Recently, Esses and her colleagues (Esses, Dovidio, Jackson, & Armstrong, 2001; Esses, Jackson, & Armstrong, 1998; Jackson & Esses, 2000) have integrated work on realistic group conflict theory (Campbell, 1965; LeVine & Campbell, 1972; Sherif, 1966; see also Bobo, 1988) and social dominance theory (Pratto, 1999; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) within the framework of the instrumental model of group conflict. This model proposes that resource stress (the perception that access to a desired resource, such as wealth or political power, is limited) and the salience of a potentially competitive out-group lead to perceived group competition for resources. Several factors may determine the degree of perceived resource stress, with the primary ones including perceived scarcity of resources and individual or group support for an unequal distribution of resources, which is closely related to social dominance orientation (Pratto et al., 1994). Moreover, resource stress is likely to lead to perceived group competition when a relevant out-group is present. Some groups are more likely to be perceived as competitors than are others. Out-groups that are salient and distinct from one’s own group are especially likely to stand out as potential competitors. However, potential competitors must also be similar to the in-group on dimensions that make them likely to take resources.That is, they must be interested in similar resources and in a position to potentially take these resources.

The combination of resource stress and the presence of a potentially competitive out-group leads to perceived group competition. Such perceived group competition is likely to take the form of zero-sum beliefs: beliefs that the more the other group obtains, the less is available for one’s own group. There is a perception that any gains that the other group might make must be at the expense of one’s own group.The model is termed the instrumental model of group conflict because attitudes and behaviors toward the competitor out-group are hypothesizedtoreflectstrategicattemptstoremovethesourceof competition. Efforts to remove the other group from competition may include out-group derogation, discrimination, and avoidance of the other group. One may express negative attitudes and attributions about members of the other group in an attempt to convince both one’s own group and other groups of the competitors’ lack of worth. Attempts to eliminate the competition may also entail discrimination and opposition to policies and programs that may benefit the other group. Limiting the other group’s access to the resources also reduces competition. Consistent with this model, Esses and her colleagues have found that individuals in Canada and the United States perceive greater threat, are more biased against, and are more motivated to exclude immigrant groups that are seen as involved in a zero-sum competition for resources with nonimmigrants (Esses et al., 1998, 2001; Jackson & Esses, 2000).

Discrimination can serve less tangible collective functions as well as concrete instrumental objectives. Blumer (1958a) acknowledged that the processes for establishing group position may involve goals such as gaining economic advantage, but they may also be associated with the acquisition of intangible resources such as prestige. Taylor (2000), in fact, suggested that symbolic, psychological factors are typically more important in intergroup bias than are tangible resources. Theoretical developments in social psychology, stimulated by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), further highlight the role of group categorization, independent of actual realistic group conflict, in motivations to achieve favorable group identities (“positive distinctiveness”) and consequently on the arousal of intergroup bias and discrimination.

Collective Identity

Human activity is rooted in interdependence. Group systems involving greater mutual cooperation have substantial survival advantages for individual group members over those systems without reciprocally positive social relations (Trivers, 1971). However, the decision to cooperate with nonrelatives (i.e., to expend resources for another’s benefit) is a dilemma of trust because the ultimate benefit for the provider depends on others’willingness to reciprocate. Indiscriminate trust and altruism that are not reciprocated are not effective survival strategies.

Social categorization and group boundaries provide a basis for achieving the benefits of cooperative interdependence without the risk of excessive costs. In-group membership is a form of contingent cooperation. By limiting aid to mutually acknowledged in-group members, total costs and risks of nonreciprocation can be contained. Thus, in-groups can be defined as bounded communities of mutual trust and obligation that delimit mutual interdependence and cooperation. The ways in which people understand their group membership thus play a critical role in social harmony and conflict.

Models of category-based processing (Brewer, 1988; see also Fiske et al., 1999) assume that “the mere presentation of a stimulus person activates certain classification processes that occur automatically and without conscious intent. . . . The process is one of ‘placing’ the individual social object along well-established stimulus dimensions such as age, gender, and skin color” (Brewer, 1988, pp. 5–6). We have further hypothesized that “a primitive type of categorization may also have a high probability of spontaneously occurring, perhaps in parallel process. This is the categorization of individuals as members of one’s ingroup or not” (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1993, p. 170). Because of the centrality of the self in social perception (Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Kihlstrom et al., 1988), we propose that social categorization involves most fundamentally a distinction between the group containing the self (the in-group) and other groups (the out-groups) between the “we’s”andthe“they’s”(seealsoTajfel&Turner,1979;Turner et al., 1987). This distinction has a profound influence on evaluations, cognitions, and behavior.

Social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and, more recently, self-categorization theory (Turner, 1985; Turner et al., 1987) address the fundamental process of social categorization. From a social categorization perspective, when people or objects are categorized into groups, actual differences between members of the same category tend to be perceptually minimized (Tajfel, 1969) and often ignored in making decisions or forming impressions. Members of the same category seem to be more similar than they actually are, and more similar than they were before they were categorized together. In addition, although members of a social category may be different in some ways from members of other categories, these differences tend to become exaggerated and overgeneralized. Thus, categorization enhances perceptions of similarities within groups and differences between groups—emphasizing social difference and group distinctiveness. This process is not benign because these within- and between-group distortions have a tendency to generalize to additional dimensions (e.g., character traits) beyond those that differentiated the categories originally (Allport, 1954, 1958). Furthermore, as the salience of the categorization increases, the magnitude of these distortions also increases (Abrams, 1985; Brewer, 1979; Brewer & Miller, 1996; Dechamps & Doise, 1978; Dion, 1974; Doise, 1978; Skinner & Stephenson, 1981; Turner, 1981, 1985).

Moreover, in the process of categorizing people into two different groups, people typically classify themselves into one of the social categories and out of the other. The insertion of the self into the social categorization process increases the emotional significance of group differences and thus leads to further perceptual distortion and to evaluative biases that reflect favorably on the in-group (Sumner, 1906), and consequently on the self (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Tajfel and Turner (1979), in their social identity theory, proposed that a person’s need for positive identity may be satisfied by membership in prestigious social groups. This need also motivates social comparisons that favorably differentiate in-group from outgroup members, particularly when self-esteem has been challenged (Hogg & Abrams, 1990). For example, Meindl and Lerner (1984) found that experiencing an esteem-lowering experience (committing an unintentional transgression) motivated people to reject an opportunity for equal status contact between the in-group and an out-group in favor of interaction that implied the more positive status of the in-group. Within social identity theory, successful intergroup discrimination is then presumed to restore, enhance, or elevate one’s selfesteem (see Rubin & Hewstone, 1998).

As we noted earlier, the social identity perspective (see also self-categorization theory; Turner et al., 1987) also proposes that a person defines or categorizes the self along a continuum that ranges at one extreme from the self as the embodiment of a social collective or group to the self as a separate individual with personal motives, goals, and achievements. Self-categorization in terms of collective identity, in turn, increases the likelihood of the development of intergroup biases and conflict (Schopler & Insko, 1992). As Sherif et al.’s (1961) initial observations revealed, intergroup relations begin to sour soon after people categorize others in terms of in-group and out-group members: “Discovery of another group of campers brought heightened awareness of ‘us’ and ‘ours’ as contrasted with ‘outsiders’ and ‘intruders,’ [and] an intense desire to compete with the other group in team games” (Sherif et al., 1961, p. 95). Thus, social categorization lays the foundation for intergroup bias and conflict that can lead to, and be further exacerbated by, competition between these groups.

Additional research has demonstrated just how powerfully mere social categorization can influence differential thinking, feeling and behaving toward in-group versus out-group members. Upon social categorization of individuals into in-groups and out-groups, people spontaneously experience more positive affect toward the in-group (Otten & Moskowitz, 2000; Otten & Wentura, 1999). They also favor in-group members directly in terms of evaluations and resource allocations (Mullen, Brown, & Smith, 1992; Tajfel, Billig, Bundy, & Flament,1971),aswellasindirectlyinvaluingtheproductsof their work (Ferguson & Kelley, 1964). In addition, in-group membership increases the psychological bond and feelings of “oneness” that facilitate the arousal of promotive tension or empathy in response to others’needs or problems (Hornstein, 1976). In part as a consequence, prosocial behavior is offered more readily to in-group than to out-group members (Dovidio et al., 1997; Piliavin, Dovidio, Gaertner, & Clark, 1981). People are also more likely to initiate “heroic” action on behalf of an in-group member than another person, for example by directly confronting a transgressor who insults the person (Meindl & Lerner, 1983). Moreover, people are more likely to be cooperative and exercise more personal restraint when using endangered common resources when these are shared with in-group members than with others (Kramer & Brewer, 1984), and they work harder for groups they identify more as theirin-group(Worchel,Rothgerber,Day,Hart,&Butemeyer, 1998).

In terms of information processing, people retain more information in a more detailed fashion for in-group members than for out-group members (Park & Rothbart, 1982), have better memory for information about ways in which in-group members are similar and out-group members are dissimilar to the self (Wilder, 1981), and remember less positive information about out-group members (Howard & Rothbart, 1980). Perhaps because of the greater self-other overlap in representations for people defined as in-group members (E. R. Smith & Henry, 1996), people process information about and make attributions to in-group members more on the basis of selfcongruency than they do for out-group members (Gramzow, Gaertner, & Sedikides, 2001).

People are also more generous and forgiving in their explanations for the behaviors of in-group relative to out-group members. Positive behaviors and successful outcomes are more likely to be attributed to internal, stable characteristics (the personality) of in-group than out-group members, whereas negative outcomes are more likely to be ascribed to the personalities of out-group members than of in-group members (Hewstone, 1990; Pettigrew, 1979). Observed behaviors of in-group and out-group members are encoded in memory at different levels of abstraction (Maass, Ceccarelli, & Rudin, 1996). Undesirable actions of out-group members are encoded at more abstract levels that presume intentionality and dispositional origin (e.g., she is hostile) than identical behaviorsofin-groupmembers(e.g.,sheslappedthegirl).Desirable actions of out-group members, however, are encoded at more concrete levels (e.g., she walked across the street holding the old man’s hand) relative to the same behaviors of in-group members (e.g., she is helpful).

Language plays another role in intergroup bias through associations with collective pronouns. Collective pronouns such as “we” or “they” that are used to define people’s in-group or out-group status are frequently paired with stimuli having strong affective connotations. As a consequence, these pronouns may acquire powerful evaluative properties of their own. These words (we, they) can potentially increase the availability of positive or negative associations and thereby influence beliefs about, evaluations of, and behaviors toward other people—often automatically and unconsciously (Perdue, Dovidio, Gurtman, & Tyler, 1990).

The process of social categorization, however, is not completely unalterable. Categories are hierarchically organized, and higher level categories (e.g., nations) are more inclusive of lower level ones (e.g., cities or towns). By modifying a perceiver’s goals, motives, past experiences, and expectations, as well as factors within the perceptual field and the situational context more broadly, there is opportunity to alter the level of category inclusiveness that will be primary in a given situation. Although perceiving people in terms of a social category is easiest and most common in forming impressions, particularly during bitter intergroup conflict, appropriate goals, motivation, and effort can produce more individuated impressions of others (Brewer, 1988; Fiske et al., 1999). This malleability of the level at which impressions are formed—from broad to more specific categories to individuated responses— is important because of its implications for altering the way people think about members of other groups, and consequently about the nature of intergroup relations.

Although functional and social categorization theories of intergroup conflict and social harmony suggest different psychological mechanisms, these approaches may offer complementary rather than necessarily competing explanations. For instance, realistic threats and symbolic threats reflect different hypothesized causes of discrimination, but they can operate jointly to motivate discriminatory behavior. W. Stephan and his colleagues (Stephan, Diaz-Loving, & Duran, 2000; Stephan & Stephan, 2000; Stephan, Ybarra, Martinez, Schwarzwald, & Tur-Kaspa, 1998) have found that personal negative stereotypes, realistic group threat, and symbolic group threat all predict discrimination against other groups (e.g., immigrants), and each accounts for a unique portion of the effect. In addition, personal-level biases and collective biases may also have separate and additive influences. Bobo and his colleagues (see Bobo, 1999) have demonstrated that group threat and personal prejudice can contribute independently to discrimination against other groups. The independence of these effects points to the importance of considering each of these perspectives for a comprehensive understanding of social conflict and integration, while at the same time reinforcing the theoretical distinctions among the hypothesized underlying mechanisms.

Given the centrality and spontaneity of the social categorization of people into in-group and out-group members, and given the important role of functional relations between groups in a world of limited resources that depend on differentiation between in-group and out-group members, how can biasbereduced?Becausecategorizationisabasicprocessthat is fundamental to prejudice and intergroup conflict, some contemporary work has targeted this process as a place to begin to improve intergroup relations. This work also considers the functional relations among groups. In the next section we explore how the forces of categorization may be disarmed or redirected to promote more positive intergroup attitudes—and potentially begin to penetrate the barriers to reconciliation among groups with a history of antagonistic relations. One of the most influential strategies involves creating and structuring intergroup contact.

Intergroup Contact and the Reduction of Bias

For the past 50 years the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954; Amir, 1969; Cook, 1985; Watson, 1947; Williams, 1947; see also Pettigrew, 1998a; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2000) has represented a promising and popular strategy for reducing intergroup bias and conflict. This hypothesis proposes that simple contact between groups is not automatically sufficient to improve intergroup relations. Rather, for contact between groups to reduce bias successfully, certain prerequisite features must be present. These characteristics of contact include equal status between the groups, cooperative (rather than competitive) intergroup interaction, opportunities for personal acquaintance between the members (especially with those whose personal characteristics do not support stereotypic expectations), and supportive norms by authorities within and outside of the contact situation (Cook, 1985; Pettigrew, 1998a). Research in laboratory and field settings generally supports the efficacy of the list of prerequisite conditions for achieving improved intergroup relations (see Pettigrew & Tropp, 2000).

Contact and Functional Relations

Consistent with functional theories of intergroup relations, changing the nature of interdependence between members of different groups from perceived competition to cooperation significantly improves intergroup attitudes (Blanchard, Weigel, & Cook, 1975; Cook, 1985; Deutsch & Collins, 1951; Green, Adams, & Turner, 1988; Stephan, 1987; Weigel, Wiser, & Cook, 1975). Cooperative learning (Slavin, 1985), jigsaw classroom interventions in which students are interdependent on one another in problem-solving exercises (Aronson & Patnoe, 1997), and more comprehensive approaches in schools that involve establishing a cooperative community, resolving conflicts, and internalizing civic values (e.g., Peacekeepers; Johnson & Johnson, 2000) also support the fundamental principles outside of the laboratory. Although it is difficult to establish all of these conditions in intergroup contact situations, the formula is effective when these conditions are met (Cook, 1984; Johnson, Johnson, & Maruyama, 1983; Pettigrew, 1998a).

Structurally, however, the contact hypothesis has represented a list of loosely connected, diverse conditions rather than a unifying conceptual framework that explains how these prerequisite features achieve their effects. This is problematic because political and socioeconomic circumstances (e.g., real or perceived competitive, zero-sum outcomes) often preclude introducing these features (e.g., cooperative interdependence, equal status) into many contact settings. Despite substantial documentation that intergroup cooperative interaction reduces bias (Allport, 1954; Aronson, Blaney, Stephan, Sikes, & Snapp, 1978; Cook, 1985; Deutsch, 1973; Johnson et al., 1983; Sherif et al., 1961; Slavin, 1985; Worchel, 1979), it is not clear how cooperation achieves this effect. One basic issue involves the psychological processes that mediate this change.

The classic functional relations perspective by Sherif et al. (1961) views cooperative interdependence as a direct mediator of attitudinal and behavioral changes. However, recent approaches have extended research on the contact hypothesis by attempting to understand the potential common processes and mechanisms that these diverse factors engage to reduce bias. Several additional explanations have been proposed (see Brewer & Miller, 1984; Miller & Davidson-Podgorny, 1987; Worchel, 1979, 1986). For example, cooperation may induce greater intergroup acceptance as a result of dissonance reduction serving to justify this type of interaction with the other group (Miller & Brewer, 1986). It is also possible that cooperation can have positive, reinforcing outcomes. When intergroup contact is favorable and has successful consequences, psychological processes that restore cognitive balance or reduce dissonance produce more favorable attitudes toward members of the other group and toward the group as a whole to be consistent with the positive nature of the interaction. In addition, the rewarding properties of achieving success may become associated with members of other groups (Lott & Lott, 1965), thereby increasing attraction (S. Gaertner et al., 1999). Also, cooperative experiences can reduce intergroup anxiety (Stephan & Stephan, 1984).

Intergroup contact can also influence how interactants conceive of the groups and how the members are socially categorized. Cooperative learning and jigsaw classroom interventions (Aronson & Patnoe, 1997), which are designed to increase interdependence between members of different groups and to enhance appreciation for the resources they bring to the task, may reduce bias in part by altering how interactants conceive of the group boundaries and memberships. In the next section we consider how the effects of intergroup contact can be mediated by changes in personal and collective identity.

Contact, Categorization, and Identity

From the social categorization perspective, the issue to be addressed is how intergroup contact can be structured to alter cognitive representations in ways that eliminate one or more of the basic features of the negative intergroup schema. Based on the premises of social identity theory, three alternative models for contact effects have been developed and tested in experimental and field settings: decategorization, recategorization, and mutual differentiation.

Each of these models can be described in terms of recommendations for how to structure cognitive representations of situations in which there is contact between the groups, the psychological processes that promote attitude change, and the mechanisms by which contact experiences are generalized to change attitudes toward the out-group as a whole. Each of these strategies targets the social categorization process as the place to begin to understand and to combat intergroup biases. Decategorization encourages members to deemphasize the original group boundaries and to conceive of themselves as separate individuals rather than as members of different groups. Mutual differentiation maintains the original group boundaries, maintaining perceptions as different groups, but in the context of intergroup cooperation during which similarities and differences between the memberships are recognized and valued. Recategorization encourages the members of both groups to regard themselves as belonging to a common, superordinate group—one group that is inclusive of both memberships.

Rather than viewing these as competing positions and arguing which one is correct, we suggest that these are complementary approaches and propose that it is more productive to consider when each strategy is most effective. To the extent that it is possible for these strategies, eithersingly or in concert, to alter perceptions of the “Us versus Them” that are reflected in conflictive intergroup relations, reductions in bias and social harmony may be accomplished. Moreover, decategorization and recategorization strategies may increase the willingness of group representatives to view the meaning of the intergroup conflict from the other group’s perspective and to offer solutions that recognize both groups’needs and concerns.

Decategorization: The Personalization Model

The first model is essentially a formalization and elaboration of the assumptions implicit in Allport’s contact hypothesis (Brewer & Miller, 1984). A primary consequence of salient in-group–out-group categorization is the deindividuation of members of the out-group. Social behavior in category-based interactions is characterized by a tendency to treat individual members of the out-group as undifferentiated representatives of a unified social category, ignoring individual differences within the group. The personalization perspective on the contact situation implies that intergroup interactions should be structured to reduce the salience of category distinctions and promote opportunities to get to know out-group members as individual persons, thereby disarming the forces of categorization.

The conditional specifications of the contact hypothesis (e.g., cooperative interaction) can be interpreted as features of the situation that reduce category salience and promote more differentiated and personalized representations of the participants in the contact setting. Interdependence typically motivates people to focus more on the individual characteristics of a person, with whom their outcomes are linked, than more general category representations (Fiske, 2000). Attending to personal characteristics of group members not only provides the opportunity to disconfirm category stereotypes, but it also breaks down the monolithic perception of the outgroup as a homogeneous unit (Wilder, 1978). In this scheme, the contact situation encourages attention to information at the individual level that replaces category identity as the most useful basis for classifying participants.

With a more differentiated representation of out-group members, there is the recognition that there are different types of out-group members (e.g., sensitive as well as tough professional hockey players), thereby weakening the effects of categorization and the tendency to minimize and ignore differences between category members. When personalized interactions occur, in-group and out-group members slide even further toward the individual side of the self as individual versus group member continuum. Members “attend to information that replaces category identity as the most useful basis for classifying each other” (Brewer & Miller, 1984, p. 288) as they engage in personalized interactions. Repeated personalized contacts with a variety of out-group members should, over time, undermine the value and meaningfulness of the social category stereotype as a source of information about members of that group. This is the process by which contact experiences are expected to generalize—via reducing the salience and meaning of social categorization in the long run (Brewer & Miller, 1996).

A number of studies provide evidence supporting this perspective on contact effects (Bettencourt, Brewer, Croak, & Miller, 1992; Marcus-Newhall, Miller, Holtz, & Brewer, 1993). Miller, Brewer, and Edwards (1985), for instance, demonstrated that a cooperative task that required personalized interaction with members of the out-group resulted not only in more positive attitudes toward out-group members in the cooperative setting but also toward other out-group members shown on a videotape, compared to cooperative contact that was task focused rather than person focused.

During personalization, members focus on information about an out-group member that is relevant to the self (as an individual rather than as a group member). Repeated personalized interactions with a variety of out-group members should over time undermine the value of the category stereotype as a source of information about members of that group. Thus, the effects of personalization should generalize to new situations as well as to heretofore unfamiliar out-group members. For the benefits of personalization to generalize, however, it is of course necessary for the identities of out-group members to be salient—at least somewhat—during the interaction to allow the group stereotype to be weakened.

Further evidence of the value of personalized interactions for reducing intergroup bias comes from data on the effects of intergroup friendships (Hamberger & Hewstone, 1997; Pettigrew, 1997; Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). For example, across samples in France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, Europeans with out-group friends were lower on measures of prejudice, particularly affective prejudice (Pettigrew, 1998a). This positive relation did not hold for other types of acquaintance relationships in work or residential settings that did not involve formation of close interpersonal relationships with members of the out-group. In terms of the direction of causality, although having more positive intergroup attitudes can increase the willingness to have cross-group friendships, path analyses indicate that the path from friendship to reduction in prejudice is stronger than the other way around (Pettigrew, 1998a).

Other research reveals three valuable extensions of the personalized contact effect. One is evidence that personal friendships with members of one out-group may lead to tolerance toward out-groups in general and reduced nationalistic pride, a process that Pettigrew (1997) refers to as deprovincialization. Thus, decategorization based on developing cross-group friendships that decrease the relative attractiveness of a person’s in-group provides increased appreciation of the relative attractiveness of other out-groups more generally.

A second extension is represented by evidence that contact effects may operate indirectly or vicariously. Although interpersonal friendship across group lines leads to reduced prejudice, even knowledge that an in-group member has befriended an out-group member has the potential to reduce bias while the salience of group identities remains high for the observer (Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe, & Ropp, 1997). A third extension relates to interpersonal processes involving the arousal of empathic feelings for an out-group member, which can increase positive attitudes toward members of that group more widely (Batson et al., 1997). Thus, personalized interaction and interpersonal processes more generally can directly and indirectly increase positive feelings for out-group members through a variety of processes that can lead to more generalized types of harmony and integration at the group level.

Recategorization: The Common In-Group Identity Model

The second social categorization model of intergroup contact and conflict reduction is also based on the premise that reducing the salience of in-group–out-group category distinctions is key to positive effects. In contrast to the decategorization approaches described earlier, however, recategorization is not designed to reduce or eliminate categorization, but rather to structure a definition of group categorization at a higher level of category inclusiveness in ways that reduce intergroup bias and conflict (Allport, 1954, p. 43).

Allport (1954, 1958) was aware of the benefits of a common in-group identity, although he regarded it as a catalyst rather than as a product of the conditions of contact:

To be maximally effective, contact and acquaintance programs should lead to a sense of equality in social status, should occur in ordinary purposeful pursuits, avoid artificiality, and if possible enjoy the sanction of the community in which they occur. While it may help somewhat to place members of different ethnic groups side by side on a job, the gain is greater if these members regard themselves as part of a team [italics added]. (Allport, 1958, p. 489)

In contrast, the common in-group identity model (S. Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993; S. Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000) proposes that group identity can be a critical mediating factor. According to this model, intergroup bias and conflict can be reduced by factors that transform participants’ representations of memberships from two groups to one, more inclusive group. With common in-group identity, the cognitive and motivational processes that initially produced in-group favoritism are redirected to benefit the common in-group, including former out-group members.

Allport’s (1954, 1958) description of widening circles of inclusion, hierarchically organized, depicts a person’s various in-group memberships from one’s family to one’s neighborhood, to one’s city, to one’s nation, to one’s race, to all of humankind. Recognizing that racial group identity had become the dominant allegiance among many White racists, Allport questioned the accuracy of the common belief that ingroup loyalties always grow weaker the larger their circle of inclusion, which might prevent loyalty to a group more inclusive than race. Rather, Allport proposed the potential value of shifting the level of category inclusiveness from race to humankind. He recognized that the “clash between the idea of race and of One World . . . is shaping into an issue that may well be the most decisive in human history. The important question is, Can a loyalty to mankind be fashioned before interracial warfare breaks out?” (pp. 43–44). But is it too difficult and unrealistic for people to identify with humankind?Allport proposed that this level of common in-group identification is difficult for most people primarily because there are few symbols that make this more ephemeral in-group real or concrete. That is, groups such as nations have symbols that include flags, buildings, and holidays, but at the international level there are few icons that help serve as anchors for unity and world loyalty. Attempts to forge superordinate cooperative alliances, therefore, would more likely engage identification processes if symbols were adopted to affirm the joint venture.

Among the antecedent factors proposed by the common in-group identity model are the features of contact situations that are necessary for intergroup contact to be successful (e.g., interdependence between groups, equal status, equalitarian norms; Allport, 1954). From this perspective, intergroup cooperative interaction, for example, enhances positive evaluations of out-group members, at least in part, because cooperation transforms members’ representations of the memberships from “Us” versus “Them” to a more inclusive “We.” In a laboratory experiment, S. Gaertner, Mann, Dovidio, Murrell, and Pomare (1990) directly tested and found strong support for the hypotheses that the relation between intergroup cooperation and enhanced favorable evaluations of out-group members was mediated by the extent to which members of both groups perceived themselves as one group. In addition, the generalizability of this effect was supported by a series of survey studies conducted in natural settings across very different intergroup contexts: bankers experiencing corporate mergers, students in a multiethnic high school, and college students from blended families (see S. Gaertner, Dovidio, & Bachman, 1996). Moreover, appeals that emphasize the common group membership of nonimmigrants and immigrants have been shown to improve attitudes toward immigrants and to increase support for immigration among people in Canada and the United States, and particularly among those high in social dominance orientation for whom group hierarchy is important (Esses et al., 2001).

These effects of recategorization on behaviors, such as helping and self-disclosure (see Dovidio et al., 1997; Nier et al., 2001), as well as on attitudes, have some extended, practical implications. Recategorization can stimulate interactions among group members in the contact situation that can in turn activate other processes, which subsequently promote more positive intergroup behaviors and attitudes. For example, both self-disclosure and helping typically produce reciprocity. More intimate self-disclosure by one person normally encourages more intimate disclosure by the other (Archer & Berg, 1978; Derlega, Metts, Petronio, & Margulis, 1993). As we discussed earlier, the work of Miller, Brewer, and their colleagues (e.g., Brewer & Miller, 1984; Miller et al., 1985) has demonstrated that personalized and selfdisclosing interaction can be a significant factor in reducing intergroup bias.

Considerable cross-cultural evidence also indicates the powerful influence of the norm of reciprocity on helping (Schroeder, Penner, Dovidio & Piliavin, 1995). According to this norm, people should help those who have helped them, and they should not help those who have denied them help for no legitimate reason (Gouldner, 1960). Thus, the development of a common in-group identity can motivate interpersonal behaviors between members of initially different groups that can initiate reciprocal actions and concessions (see Deutsch, 1993; Osgood, 1962). These reciprocal actions and concessions not only will reduce immediate tensions but also can produce more harmonious intergroup relations beyond the contact situation.

Although finely differentiated impressions of out-group members may not be an automatic consequence of forming a common in-group identity, these more elaborated, differentiated, and personalized impressions can quickly develop because the newly formed positivity bias is likely to encourage more open communication (S. Gaertner et al., 1993). The development of a common in-group identity creates a motivational foundation for constructive intergroup relations that can act as a catalyst for positive reciprocal interpersonal actions. Thus, the recategorization strategy proposed in our model as well as decategorization strategies, such as individuating (Wilder, 1984) and personalizing (Brewer & Miller, 1984) interactions, can potentially operate complementarily and sequentially to improve intergroup relations in lasting and meaningful ways.

Challenges to the Decategorization and Recategorization Models

Although the structural representations of the contact situation advocated by the decategorization (personalization) and recategorization (common in-group identity) models are different, the two approaches share common assumptions about the need to reduce category differentiation and associated processes. Because both models rely on reducing or eliminating the salience of intergroup differentiation, they involve structuring contact in a way that will challenge or threaten existing social identities. However, both cognitive and motivational factors conspire to create resistance to the dissolution of category boundaries or to reestablish category distinctions over time. Although the salience of a common superordinate identity or personalized representations may be enhanced in the short run, then, these may be difficult to maintain across time and social situations.

Brewer’s (1991) optimal distinctiveness model of the motives underlying group identification provides one explanation for why category distinctions are difficult to change. The theory postulates that social identity is driven by two opposing social motives: the need for inclusion and the need for differentiation. Human beings strive to belong to groups that transcend their own personal identity, but at the same time they need to feel special and distinct from others. In order to satisfy both of these motives simultaneously, individuals seek inclusion in distinctive social groups where the boundaries between those who are members of the in-group category and those who are excluded can be drawn clearly. On the one hand, highly inclusive superordinate categories do not satisfy distinctiveness needs. Thus, inclusive identities, which may not be readily accepted, may be limited in their capacity to reduce bias (Hornsey & Hogg, 2000a, 2000b). On the other hand, high degrees of individuation fail to meet needs for belonging and for cognitive simplicity and uncertainty reduction (Hogg & Abrams, 1993). These motives are likely to make either personalization or common in-group identity temporally unstable solutions to intergroup discrimination and prejudice.

Preexisting social-structural relations between groups may also create strong forces of resistance to changes in category boundaries.Evenintheabsenceofovertconflict,asymmetries between social groups in size, power, or status create additional sources of resistance. When one group is substantially smaller than the other in the contact situation, the minority category is especially salient, and minority group members may be particularly reluctant to accept a superordinate category identity that is dominated by the other group. Another major challenge is created by preexisting status differences between groups, where members of both high- and low-status groups may be threatened by contact and assimilation (Mottola, 1996).

The Mutual Differentiation Model

These challenges to processes of decategorization/recategorization led Hewstone and Brown (1986) to recommend an alternative approach to intergroup contact in which cooperative interactions between groups are introduced without degrading the original in-group–out-group categorization. More specifically, this model favors encouraging groups working together to perceive complementarity by recognizing and valuing mutual assets and weaknesses within the context of an interdependent cooperative task or common, superordinate goals. This strategy allows group members to maintain their social identities and positive distinctiveness while avoiding insidious intergroup comparisons. Thus, the mutual intergroup differentiation model does not seek to change the basic category structure of the intergroup contact situation, but to change the intergroup affect from negative to positive interdependence and evaluation.

In order to promote positive intergroup experience, Hewstone and Brown (1986) recommended that the contact situation be structured so that members of the respective groups have distinct but complementary roles to contribute toward common goals. In this way, both groups can maintain positive distinctiveness within a cooperative framework. Evidence in support of this approach comes from the results of an experiment by Brown and Wade (1987) in which work teams composed of students from two different faculties engaged in a cooperative effort to produce a two-page magazine article. When the representatives of the two groups were assigned separate roles in the team task (one group working on figures and layout, the other working on text), the contact experiencehadamorepositiveeffectonintergroupattitudesthan when the two groups were not provided with distinctive roles (see also Deschamps & Brown, 1983; Dovidio, Gaertner, & Validzic, 1998).

Hewstone and Brown (1986) argued that generalization of positive contact experiences is more likely when the contact situation is defined as an intergroup situation rather than as an interpersonal interaction. Generalization in this case is direct rather than requiring additional cognitive links between positive affect toward individuals and toward representations of the group as a whole. This position is supported by evidence, reviewed earlier, that cooperative contact with a member of an out-group leads to more favorable generalized attitudes toward the group as a whole when category membership is made salient during contact (e.g., Brown, Vivian, & Hewstone, 1999; van Oudenhoven, Groenewoud, & Hewstone, 1996).

Although in-group–out-group category salience is usually associated with in-group bias and the negative side of intergroup attitudes, cooperative interdependence is assumed to override the negative intergroup schema, particularly if the two groups have differentiated, complementary roles to play. Because it capitalizes on needs for distinctive social identities, the mutual intergroup differentiation model provides a solution that is highly stable in terms of the cognitivestructural aspects of the intergroup situation. The affective component of the model, however, is likely to be less stable. Salient intergroup boundaries are associated with mutual distrust (Schopler & Insko, 1992), which undermines the potential for cooperative interdependence and mutual liking over any length of time. By reinforcing perceptions of group differences, this differentiation model risks reinforcing negative beliefs about the out-group in the long run; intergroup anxiety (Greenland & Brown, 1999; Islam & Hewstone, 1993) and the potential for fission and conflict along group lines remain high.

In addition, theoretical approaches and interventions are often guided by the perspective of the majority group. Indeed, because the majority group typically possesses the resources, focusing strategies for reducing conflict and enhancing social harmony on the majority group have considerable potential. However, it is not enough, and without considering all of the groups involved, these strategies can be counterproductive. Intergroup relations need to be understood from the perspective of each of the groups involved. We consider the issue of multiple perspectives in the next section.

Harmony and Integration: Majority and Minority Perspectives

The perspectives that majority and minority group members take on particular interactions and on intergroup relations in general may differ in fundamental ways. The attributions and experiences of people in seemingly identical or comparable situations may be affected by ethnic or racial group membership (see Crocker & Quinn, 2001). In the United States, Blacks perceive less social and economic opportunity than do Whites (Schuman, Steeh, Bobo, & Krysan, 1997). Crossculturally, the generally nonstigmatized ethnic and racial majorities perceive intergroup contact more positively than do minorities (S. Gaertner, Rust, Dovidio, Bachman, & Anastasio, 1996; Islam & Hewstone, 1993). Distinctiveness, associated with numerical minority status or the salience of physical or social characteristics, can exacerbate feelings of stigmatization among members of traditionally disadvantaged groups (e.g., Kanter, 1977; Niemann & Dovidio, 1998).

More generally, group status has profound implications for the experience of individuals, their motivations and aspirations, and their orientations to members of their own group and of other groups. As Ellemers and Barreto (2001) outlined, responses to the status of one’s group depend on whether one is a member of a low- or high-status group, the importance of the group to the individual (i.e., strength of identification), the perceived legitimacy of the status differences, and the prospects for change at the individual or group level (see also Branscombe & Ellemers, 1998). Wright (2001; see also Tajfel & Turner, 1979) further proposed that people in low-status groups will be motivated to pursue collective action on behalf of their group, rather than seek personal mobility, when they identify strongly with the group or when possibilities for individual mobility are limited, when intergroup comparisons produce perceptions of disadvantage and that disadvantage is viewed as illegitimate, and when people believe that the intergroup hierarchy can change and the in-group has the resources to change it. Although collective action may have long-term benefits in achieving justice and equality, in the short-term the conditions that facilitate collective action may intensify social categorization of members of the in-group and out-groups, temporarily increase conflict, and reduce the likelihood of harmony or integration between groups.

Racial and ethnic identities are unlikely to be readily abandoned because they are frequently fundamental aspects of individuals’self-concepts and esteem and are often associated with perceptions of collective injustice. Moreover, when such identities are threatened, for example by attempts to produce a single superordinate identity at the expense of one’s racial or ethnic group identity, members of these groups may respond in ways that reassert the value of the group (e.g., with disassociation from the norms and values of the larger society; see Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Steele, 1997) and adversely affect social harmony.

In addition, efforts to incorporate minority groups within the context of a superordinate identity may also produce negative responses from the majority group. Mummendey and Wenzel (1999) argued that because the standards of the superordinate group will primarily reflect those of the majority subgroup, the minority out-group will tend to be viewed as nonnormative and inferior by those standards, which can exacerbate intergroup bias among majority group members and increase group conflict. In contrast, S. Gaertner and Dovidio (2000) have proposed that the simultaneous existence of superordinate and subordinate group representations (i.e., dual- or multiple-identities) may not only improve intergroup relations (see also Hornsey & Hogg, 2000a, 2000b) but also may contribute to the social adjustment, psychological adaptation, and overall well-being of minority group members (LaFromboise, Coleman, & Gerton, 1993). Therefore, identifying the conditions under which a dual identity serves to increase or diffuse intergroup conflict is an issue actively being pursued by contemporary researchers.

There is evidence that intergroup benefits of a strong superordinate identity can be achieved for both majority and minority group members when the strength of the subordinate identity is high, regardless of the strength of subordinate group identities. For example, in a survey study of White adults, H. J. Smith and Tyler (1996, Study 1) measured the strengths of respondents’ superordinate identity as “American” and also the strengths of their subordinate identification as “White.” Respondents with a strong American identity, independent of the degree to which they identified with being White, were more likely to base their support for affirmative action policies that would benefit Blacks and other minorities on relational concerns regarding the fairness of congressional representatives than on concerns about whether these policies would increase or decrease their own well-being. However, for those who had weak identification with beingAmerican and primarily identified themselves with being White, their position on affirmative action was determined more strongly by concerns regarding the instrumental value of these policies for themselves. This pattern of findings suggests that a strong superordinate identity (such as beingAmerican) allows individuals to support policies that would benefit members of other racial subgroups without giving primary consideration to their own instrumental needs.

Among minorities, even when racial or ethnic identity is strong, perceptions of a superordinate connection enhance interracial trust and acceptance of authority within an organization. Huo, Smith, Tyler, and Lind (1996) surveyed White, Black, Latino, and Asian employees of a public-sector organization. Identification with the organization (superordinate identity) and racial-ethnic identity (subgroup identity) were independently assessed. Regardless of the strength of racialethnic identity, respondents who had a strong organizational identity perceived that they were treated fairly within the organization, and consequently they had favorable attitudes toward authority. Huo et al. (1996) concluded that having a strong identification with a superordinate group can redirect people from focusing on their personal outcomes to concerns about “achieving the greater good and maintaining social stability” (pp. 44–45), while also maintaining important racial and ethnic identities.

- Gaertner et al. (1996) found converging evidence in a survey of students in a multiethnic high school. In particular, they compared students who identified themselves on the survey using a dual identity (e.g., indicating they were Korean and American) with those who used only a single subgroup identity (e.g., Korean). Supportive of the role of a dual identity, students who described themselves both as Americans and as members of their racial or ethnic group had less bias toward other groups in the school than did those who described themselves only in terms of their subgroup identity. Also, the minority students who identified themselves using a dual identity reported lower levels of intergroup bias in general relative to those who used only their ethnic or racial group identity.

Not only do Whites and racial and ethnic minorities bring different values, identities, and experiences to intergroup contact situations, but also these different perspectives can shape perceptions of and reactions to the nature of the contact. Blumer (1958a) proposed that group status is a fundamental factor in the extent of and type of threat that different groups experience. Recent surveys reveal, for example, that Blacks show higher levels of distrust and greater pessimism about intergroup relations than do Whites (Dovidio & Gaertner, 1998; Hochschild, 1995). Majority group members tend to perceive intergroup interactions as more harmonious and productive than do minority group members (S. Gaertner et al., 1996; Islam & Hewstone, 1993; see also the survey of college students discussed earlier), but they also tend to perceive subordinate and minority groups as encroaching on their rights and prerogatives (Bobo, 1999). In addition, majority and minority group members have different pBibliography: for the ultimate outcomes of intergroup contact. Whereas minority group members often tend to want to retain their cultural identity, majority group members may favor the assimilation of minority groups into one single culture (a traditional melting potorientation):thedominantculture(e.g.,Horenczyk,1996).

Berry (1984; Berry, Poortinga, Segall, & Dasen, 1992) presented four forms of cultural relations in pluralistic societies that represent the intersection of “yes–no” responses to two relevant questions: (a) Is cultural identity of value, and to be retained? (b) Are positive relations with the larger society of value, and to be sought? These combinations reflect four adaptation strategies for intergroup relations: (a) integration, when cultural identities are retained and positive relations with the larger society are sought; (b) separation, when cultural identities are retained but positive relations with the larger society are not sought; (c) assimilation, when cultural identities are abandoned and positive relations with the larger society are desired; and (d) marginalization, when cultural identities are abandoned and are not replaced by positive identification with the larger society.

Research in the area of immigration suggests that immigrant groups and majority groups have different pBibliography: for these different types of group relations. Van Oudenhoven, Prins, and Buunk (1998) found in the Netherlands that Dutch majority group members preferred an assimilation of minority groups (in which minority group identity was abandoned and replaced by identification with the dominant Dutch culture), whereas Turkish and Moroccan immigrants most strongly endorsed integration (in which they would retain their own cultural identity while also valuing the dominant Dutch culture).

These preferences also apply to the preferences of Whites and minorities about racial and ethnic group relations in the United States. Dovidio, Gaertner, and Kafati (2000) have found that Whites prefer assimilation most, whereas racial and ethnic minorities favor pluralistic integration. Moreover, these preferred types of intergroup relations for majority and minority groups—a one-group representation (assimilation) for Whites and dual representation (pluralistic integration) for racial and ethnic minorities—differentially mediated the consequences of intergroup contact for the different groups. Specifically, for Whites, more positive perceptions of intergroup contact related to stronger superordinate (i.e., common group) representations, which in turn mediated more positive attitudes to their school and other groups at the school. In contrast, for minority students, a dual-identity (integration) representation—but not the one-group representation—predicted more positive attitudes toward their school and to other groups. In general, these effects were stronger for people higher in racial-ethnic identification, both for Whites and minorities.

These findings have practical as well as theoretical implications for reducing intergroup conflict and enhancing social harmony. Although correlational data should be interpreted cautiously, it appears that for both Whites and racial and ethnic minorities, favorable intergroup contact may contribute to their commitment to their institution. However, strategies and interventions designed to enhance satisfaction need to recognize that Whites and minorities may have different ideals and motivations. Because White values and culture have been the traditionally dominant ones in the United States, American Whites may see an assimilation model—in which members of other cultural groups are absorbed into the mainstream—as the most comfortable and effective strategy. For racial and ethnic minorities, this model, which denies the value of their culture and traditions, may be perceived not only as less desirable but also as threatening to their personal and social identity—particularly for people who strongly identify with their group. Thus, efforts to create a single superordinate identity, though well intentioned, may threaten one’s social identity, which in turn can intensify intergroup bias and conflict. As Bourhis, Moise, Perrault, and Sebecal (1997) argued with respect to the nature of immigrant and host community relations, conflict is likely to be minimized and social harmony fostered when these groups have consonant acculuration ideals and objectives.

Conclusions

In this research paper we have examined the fundamental psychological processes related to intergroup relations, group conflict, social harmony, and intergroup integration. Intergroup bias and conflict are complex phenomena having historical, cultural, economic, and psychological roots. In addition, these are dynamic phenomena that can evolve to different forms and manifestations over time. A debate about whether a societal, institutional, intergroup, or individual level of analysis is most appropriate, or a concern about which model of bias or bias reduction accounts for the most variance, not only may thus be futile but may also distract scholars from a more fundamental mission: developing a comprehensive model of social conflict, harmony, and integration.

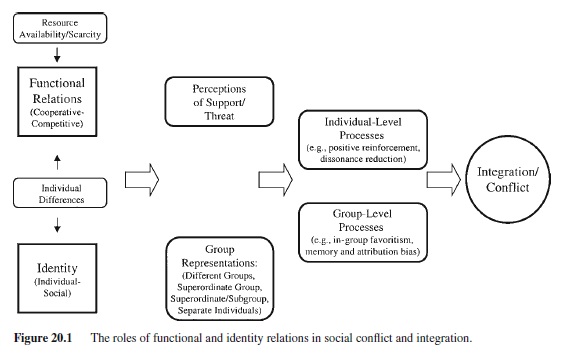

We propose that understanding how structural, social, and psychological mechanisms jointly shape intergroup relations can have both valuable theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, individual difference (e.g., social dominance orientation;Sidanius&Pratto,1999),functional(e.g.,Sherif& Sherif, 1969), and collective identity (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner et al., 1987) approaches can be viewed as complementary rather than competing explanations for social conflict and harmony (see Figure 20.1). Conceptually, intergroup relations are significantly influenced by structural factors as well as by individual orientations toward intergroup relations (e.g., social dominance orientation; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999) and toward group membership (e.g., strength of identification) and by the nature of collective identity. Functional relations within and between groups and social identity can influence perceptions of intra- and intergroup support or threat as well as the nature of group representations (see Figure 20.1). For instance, greater dependence on in-group members can strengthen the perceived boundaries, fostering representations as members of different groups and increasing perceptions of threat (L. Gaertner & Insko, 2000). Empirically, self-interest, realistic group threat, and identity threat have been shown independently to affect intergroup relations adversely (Bobo, 1999; Esses et al., 1998; Stephan & Stephan, 2000). Perceptions of intergroup threat or support and group representations can also mutually influence one another. Perceptions of competition or threat increase the salience of different group representations and decrease the salience of superordinate group connections, whereas stronger inclusive representations of the groups can decrease perceptions of intergroup competition (S. L. Gaertner et al., 1990).

Similarly, within the social categorization approach, researchers have posited not only that decategorization, recategorization, and mutual intergroup differentiation processes can each play a role in the reduction of bias over time (Pettigrew, 1998a), but also that these processes can facilitate each other reciprocally (S. L. Gaertner et al., 2000; Hewstone, 1996). Within an alternating sequence of categorization processes, mutual differentiation may emerge initially to neutralize threats to original group identities posed by the recategorization and decategorization processes. Once established, mutual differentiation can facilitate the subsequent recognition and acceptance of a salient superordinate identity and recategorization, which would have previously stimulated threats to the distinctiveness of group identities (S. Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000).