View sample psychological behaviorism theory of personality research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

This research paper has several aims. One is that of considering the role of behaviorism and behavioral approaches in the fields of personality theory and measurement. A second and central aim is that of describing a particular and different behavioral approach to the fields of personality theory and personality measurement. A third concern is that of presenting some of the philosophy- and methodology-of-science characteristics of this behavioral approach relevant to the field of personality theory. A fourth aim is to characterize the field of personality theory from the perspective of this philosophy and methodology of science. And a fifth aim is to project some developments for the future that derive from this theory perspective. Addressing these aims constitutes a pretty full agenda that will require economical treatment.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Behavioral Approaches and Personality

Behavioral approaches to personality might seem of central importance to personology because behaviorism deals with learning and it is pretty generally acknowledged that learning affects personality. Moreover, behaviorist theories were once the models of what theory could be in psychology. But certain features militate against behaviorism’s significance for the field of personality. Those features spring from the traditional behaviorist mission.

Traditional Behaviorism and Personality

One feature is behaviorism’s search for general laws. That is ingrained in the approach, as we can see from its strategy of discovering learning-behavior principles with rats, pigeons, dogs, and cats—for the major behaviorists in the first and second generation were animal psychologists who assumed that those learning-behavior principles would constitute a complete theory for dealing with any and all types of human behavior. John Watson, in behaviorism’s first generation, showed this, as B. F. Skinner did later. Clark Hull (1943) was quite succinct in stating unequivocally about his theory that “all behavior, individual and social, moral and immoral, normal and psychopathic, is generated from the same primary laws” (p. v). Even Edward Tolman’s goal, which he later admitted was unreachable, was to constitute through animal study a general theory of human behavior. The field of personality, in contrast, is concerned with individual differences, with humans, and this represents a schism of interests.

A second, even more important, feature of behaviorism arises in the fact that personality as conceived in personology lies within the individual, where it cannot be observed. That has always raised problems for an approach that placed scientific methodology at its center and modeled itself after logical positivism and operationism.Watson had decried as mentalistic the inference of concepts of internal, unobservable causal processes. For him personality could only be considered as the sum total of behavior, that is, as an observable effect, not as a cause. Skinner’s operationism followed suit. This, of course, produced another, even wider, schism with personology because personality is generally considered an internal process that determines external behavior. That is the raison d’être for the study of personality.

Tolman, who along with Hull and Skinner was one of the most prominent second-generation behaviorists, sought to resolve the schism in his general theory. As a behaviorist he was concerned with how conditioning experiences, the independent variable, acted on the organism’s responding, the dependent variable. But he posited that there was something in between: the intervening variable, which also helped determine the organism’s behavior. Cognitions were intervening variables. Intelligence could be an intervening variable. This methodology legitimated a concept like personality.

However, the methodology was anathema to Skinner. Later, Hull and Kenneth Spence (1944) took the in-between position that intervening variables should be considered just logical devices, not to be interpreted as standing for any real psychological events within the individual. These differences were played out in literature disputes for some time. That was not much of a platform for constructing psychology theory such as personology. The closest was Tolman’s consideration of personality as an intervening variable. But he never developed this concept, never stipulated what personality is, never derived a program of study from the theory, and never employed it to understand any kind of human behavior. Julian Rotter (1954) picked upTolman’s general approach, however, and elaborated an axiomatic theory that also drew from Hull’s approach to theory construction.As was true for Hull, the axiomatic construction style of the theory takes precedence over the goal of producing a theory that is useful in confronting the empirical events to which the theory is addressed.

To exemplify this characteristic of theory, Rotter’s social learning has no program to analyze the psychometric instruments that stipulate aspects of personality, such as intelligence, depression, interests, values, moods, anxiety, stress, schizophrenia, or sociopathy. His social learning theory, moreover, does not provide a theory of what personality tests are and do. Nor does the theory call for the study of the learning and functions of normal behaviors such as language, reading, problem-solving ability, or sensorimotor skills. The same is true with respect to addressing the phenomena of abnormal behavior. For example, Rotter (1954) described the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) but in a very conventional way. There are no analyses of the different personality traits measured on the test in terms of their behavioral composition or of the independent variables (e.g., learning history) that result in individual differences in these and other traits. Nor are there analyses of how individual differences in traits affect other people’s responses to the individuals or of how individual differences in the trait in turn act on the individual’s behavior. For example, a person with a trait of paranoia is more suspicious than others are. What in behavioral terms does being suspicious consist of, how is that trait learned, and how does it have its effects on the person’s behavior and the behavior of others? The approach taken here is that a behavioral theory of personality must analyze the phenomena of the field of personality in this manner. Rotter’s social learning theory does not do these things, nor do the other social learning theories.

Rather, his theory inspired academic studies to test his formal concepts such as expectancy, need potential, need value, freedom of movement, and the psychological situation. This applied even to the personality-trait concept he introduced, the locus of control—whether people believe that they themselves, others, or chance determines the outcome of the situations in which the individuals find themselves.Although it has been said that this trait is affected in childhood by parental reward for desired behaviors, studies to show that differential training of the child produces different locus-of-control characteristics remain to be undertaken.Tyler, Dhawan, and Sinha (1989) have shown that there is a class difference in locus of control (measured by self-report inventory). But this does not represent a program for studying learning effects even on that trait, let alone on the various aspects of personality.

The social learning theories of Albert Bandura and Walter Mischel are not considered here. However, each still carries the theory-oriented approach of second-generation behaviorism in contrast to the phenomena-oriented theory construction of the present approach. For example, there are many laboratory studies of social learning theory that aim to show that children learn through imitation. But there are not programs to study individual differences in imitation, the cause of such differences, and how those differences affect individual differences in important behaviors (e.g., the ability to copy letters, learn new words, or accomplish other actual learning tasks of the child). Bandura’s approach actually began in a loose social learning framework. Then it moved toward a behavioral approach several years later, drawing on the approach to be described here as well as the approach of Skinner, and later it moved toward including a more cognitive terminology. Mischel (1968) first took a Watsonian-Skinnerian approach to personality and assessment, as did other radical behaviorists. He later abandoned that position (Mischel, 1973) but, like the other social learning theorists, offered no program for study stipulating what personality is, how it is learned, how it functions, and how personality study relates to psychological measurement.

When all is said and done, then, standard behaviorism has not contributed a general and systematic program for the study of personality or personality measurement. It has features that interfere with doing so. Until they are overcome in a fundamental way (which Tolmanian social learning approaches did not provide), those features represent an impassable barrier.

Behavior Therapy and Personality

The major behaviorists such as Hull, Skinner, and Tolman were animal learning researchers. None of them analyzed the learning of functional human behaviors or traits of behavior. Skinner’s empirical approach to human behavior centered on the use of his technology, that is, his operant conditioning apparatus. His approach was to use this “experimental analysis of behavior” methodology in studying a simple, repetitive response of a subject that was automatically reinforced (and recorded). That program was implemented by his students in studies reinforcing psychotic patients, individuals with mental retardation, and children with autism with edibles and such for pulling a knob. Lovaas (1977), in the best developed program among this group, did not begin to train his autistic children in language skills until after the psychological behaviorism (PB) program to be described had provided the foundation. Although Skinner is widely thought to have worked with children’s behavior, that is not the case. He constructed a crib for infants that was air conditioned and easy to clean, but the crib had no learning or behavioral implications or suggestions. He also worked with programmed learning, but that was a delimited technology and did not involve behavior analyses of the intellectual repertoires taught, and the topic played out after a few years. Skinner’s experimental analysis of behavior did not indicate how to research functional human behaviors or problems of behavior or how they are learned.

Behavior Therapy

The original impetus for the development of behavior therapy (which in the present usage includes behavior modification, behavior analysis, cognitive behavior therapy, and behavior assessment) does not derive from Hull, Skinner, Tolman, or Rotter, although they and Dollard and Miller (1950) helped stimulate a general interest in the possibility of applications. One of the original sources of behavior therapy came from Great Britain, where a number of studies were conducted of simple behavior problems treated by using conditioning principles, either classical conditioning or reinforcement. The learning framework was not taken from an American behaviorist’s theory but from European developments of conditioning principles.As an example, Raymond (see Eysenck, 1960) treated a man with a fetish for baby carriages by classical conditioning. The patient’s many photographs of baby carriages were presented singly as conditioned stimuli paired with an aversive unconditioned stimulus. Under this extended conditioning the man came to avoid the pictures and baby carriages. The various British studies using conditioning were collected in a book edited by Hans Eysenck (1960). Another of the foundations of behavior therapy came from the work of Joseph Wolpe. He employed Hull’s theory nominally and loosely in several endeavors, including his systematic desensitization procedure for treating anxiety problems. It was his procedure and his assessment of it that were important.

A third foundation of behavior therapy came from my PB approach that is described here.As will be indicated, it began with a very broad agenda, that of analyzing human behavior generally employing its learning approach, including behaviors in the natural situation. Its goal included making analyses of and treating problems of specific human behavior problems of interest to the applied areas of psychology. Following several informal applications, my first published analysis of a behavior in the naturalistic situation concerned a journal report of a hospitalized schizophrenic patient who said the opposite of what was called for. In contrast to the psychodynamic interpretation of the authors, the PB analysis was that the abnormal behavior was learned through inadvertent reinforcement given by the treating doctors. This analysis suggested the treatment—that is, not to reinforce the abnormal behavior, the opposite speech, on the one hand, and to reinforce normal speech, on the other (Staats, 1957). This analysis presented what became the orientation and principles of theAmerican behavior modification field: (a) deal with actual behavior problems, (b) analyze them in terms of reinforcement principles, (c) take account of the reinforcement that has created the problem behavior, and (d) extinguish abnormal or undesirable behavior through nonreinforcement while creating normal behavior by reinforcement.

Two years later, my long-time friend and colleague Jack Michael and his student Teodoro Ayllon (see Ayllon & Michael, 1959), used this analysis of psychotic behavior and these principles of behavior modification to treat behavioral symptoms in individual psychotic patients in a hospital. Their study provided strong verification of the PB behavior modification approach, and its publication in a Skinnerian journal had an impact great enough to be called the “seeds of the behavioral revolution” by radical behaviorists (Malott, Whaley, & Malott, 1997, p. 175).Ayllon and Michael’s paper was written as though this approach derived from Skinnerian behaviorism and this error was repeated in many works that came later. For example, Fordyce (see 1990) followed Michael’s suggestion both in using the PB principles and in considering his pain theory to be Skinnerian.

The study of child behavior modification began similarly. Following my development of the behavior modification principles with simple problems, I decided that a necessary step was to extend behavior analysis to more complex behavior that required long-term treatment.At UCLA(where I took my doctoral degree in general experimental and completed clinical psychology requirements) I had worked with dyslexic children. Believing that reading is crucially important to human adjustment in our society, I selected this as a focal topic of study—both remedial training as well as the original learning of reading. My first study—done with Judson Finley, Karl Minke, Richard Schutz, and Carolyn Staats—was exploratory and was used in a research grant application I made to the U.S. Office of Education. The study was based on my view that the central problem in dyslexia is motivational. Children fail in learning because their attention and participation are not maintained in the long, effortful, and nonreinforcing (for many children) learning task that involves thousands and thousands of learning trials. In my approach the child was reinforced for attending and participating, and the training materials I constructed ensured that the child would learn everything needed for good performance. Because reading training is so extended and involves so many learning trials, it is necessary to have a reinforcing system for the long haul, unlike the experimental analysis of behavior studies with children employing simple responses and M&Ms. I thus introduced the token reinforcer system consisting of poker chips backed up by items the children selected to work for (such as toys, sporting equipment, and clothing). When this token reinforcer system was adopted for work with adults, it was called the token economy (see Ayllon & Azrin, 1968) and, again, considered part of Skinner’s radical behaviorism.

With the training materials and the token reinforcement, the adolescents who had been poor students became attentive, worked well, and learned well. Thus was the token methodology born, a methodology that was to be generally applied. In 1962 and 1964 studies we showed the same effect with preschool children first learning to read. Under reinforcement their attention and participation and their learning of reading was very good, much better than that displayed by the usual four-year-old. But without the extrinsic reinforcement, their learning behavior deteriorated, and learning stopped. In reporting this and the treatment of dyslexia (Staats, 1963; Staats & Butterfield, 1965; Staats, Finley, Minke, & Wolf, 1964; Staats & Staats, 1962), I projected a program for using these child behavior modification methods in studying a wide variety of children’s (and adults’) problems. The later development of the field of behavior modification showed that this program functioned as a blueprint for the field that later developed. (The Sylvan Learning Centers also use methods similar to those of PB’s reading treatments, with similar results.)

Let me add that I took the same approach in raising my own children, selecting important areas to analyze for the application of learning-behavior principles to improve and advance their development as well as to study the complex learning involved. For example, in 1960 I began working with language development (productive and receptive) when my daughter was only several months old, with number concepts at the age of a year and a half, with reading at 2 years of age. I have audiotapes of this training with my daughter, which began in 1962 and extended for more than 5 years, and videotapes with my son and other children made in 1966. Other aspects of child development dealt with as learned behaviors include toilet training, counting, number operations, writing, walking, swimming, and throwing and catching a ball (see Staats, 1996). With some systematic training the children did such things as walk and talk at 9 months old; read letters, words, sentences, and short stories at 2.5 years of age; and count unarrangedobjectsat2years(aperformancePiagetsuggested was standard at the age of 6 years). The principles were also applied to the question of punishment, and I devised time-out as a mild but effective punishment, first used in the literature by one of my students, Montrose Wolf (Wolf, Risely, & Mees, 1964).

Traditional behaviorism was our background. However, the research developed in Great Britain and by Wolpe and by me and a few others constituted the foundation for the field of behavior therapy. And this field now contains a huge number of studies demonstrating that conditioning principles apply to a variety of human behavior problems, in children and adults, with simple and complex behavior. There can be no question in the face of our behavior therapy evidence that learning is a centrally important determinant of human behavior.

The State of Personality Theory and Measurement in the Field of Behavior Therapy

Behaviorism began as a revolution against traditional psychology. The traditional behaviorist aim in analyzing psychology’s studied phenomena was to show behaviorism’s superiority and that psychology’s approach should be abandoned. In radical behaviorism no recognition is given still that work in traditional psychology has any value or that it can be useful in a unification with behaviorism. This characteristic is illustrated by the Association of Behavior Analysis’s movement in the 1980s to separate the field from the rest of psychology. It took a PB publication to turn this tide, but the isolationism continues to operate informally. Radical behaviorism students are not trained in psychology, or even in the general field of behaviorism itself. While many things from the “outside” have been adopted by radical behaviorism, some quite inconsistent with Skinner’s views, they are accepted only when presented as indigenous developments. Radical behaviorism students are taught that all of their fundamental knowledge arose within the radical behaviorism program, that the program is fully self-sufficient.

Psychological behaviorism, in conflict with radical behaviorism, takes the different view: that traditional psychology has systematically worked in many areas of human behavior and produced valuable findings that should not be dismissed sight unseen on the basis of simplistic behaviorist methodological positions from the past. Psychology’s knowledge may not be complete. It may contain elements that need to be eliminated. And it may need, but not include, the learningbehavior perspective and substance. But the PB view has been that behaviorism has the task of using traditional psychology knowledge, improving it, and behaviorizing it. In that process, behaviorism becomes psychologized itself, hence the name of the present approach. PB has aimed to discard the idiosyncratic, delimiting positions of the radical behaviorism tradition and to introduce a new, unified tradition with the means to effect the new developments needed to create unification.

An example can be given here of the delimiting effect of radical behaviorism with respect to psychological measurement. Skinner insisted that the study of human behavior was to rest on his experimental analysis of behavior (operant conditioning) methodology. Among other things he rejected selfreport data (1969, pp. 77–78). Following this lead, a general position in favor of direct observation of specific behavior, not signs of behavior, was proposed by Mischel, as well as Kanfer, and Phillips, and this became a feature of the field of behavioral assessment. The view became that psychological tests should be abandoned in favor of Skinner’s experimental analysis of behavior methodology, an orientation that could not yield a program for unification of the work of the fields of personality and psychological measurement with behavior therapy, behavior analysis, and behavioral assessment.

It may be added that PB, by contributing foundations to behavior therapy, had the anomalous effect of creating enthusiasm for a radical behaviorism that PB in good part rejects. For example, PB introduced the first general behavioral theory of abnormal behavior and a program for treatment applications (see Staats, 1963, chaps. 10 & 11), as well as a foundation for the field of behavioral assessment:

Perhaps [this] rationale for learning [behavioral] psychotherapy will also have to include some method for the assessment of behavior. In order to discover the behavioral deficiencies, the required changes in the reinforcing system [the individual’s emotional-motivational characteristics], the circumstances in which stimulus control is absent, and so on, evaluational techniques in these respects may have to be devised. Certainly, no two individuals will be alike in these various characteristics, and it may be necessary to determine such facts for the individual prior to beginning the learning program of treatment.

Such assessment might take a form similar to some of the psychological tests already in use. . . . [H]owever, . . . a general learning rationale for behavior disorders and treatment will suggest techniques of assessment. (Staats, 1963, pp. 508–509)

At that time there was no other broad abnormal psychologybehavioral treatment theory in the British behavior therapy school, in Wolpe’s approach, or in radical behaviorism. But PB’s projections, including creation of a field of behavioral assessment, were generally taken up by radical behaviorists. Thus, despite its origins within PB (as described in Silva, 1993), the field of behavioral assessment was developed as a part of radical behaviorism. However, the radical behaviorism rejection of traditional psychological measurement doomed the field to failure.

That was quite contrary to the PB plan. In the same work that introduced behavioral assessment, PB unified traditional psychological testing with behavior assessment. Behavior analyses of intelligence tests (Staats, 1963, pp. 407–411) and interest, values, and needs tests (Staats, 1963, pp. 293–306) were begun. The latter three types of tests were said to measure what stimuli are reinforcing for the individual. MacPhillamy and Lewinsohn (1971) later constructed an instrument to measure reinforcers that actually put the PB analysis into practice. Again, despite using traditional rating techniques that Skinner (1969, pp. 77–78) rejected, they replaced their behavioral assessment instrument in a delimiting radical behaviorism framework. Thus, when presented in the radical behaviorism framework, this and the other behavioral assessment works referenced earlier were separated from the broader PB framework that included the traditional tests of intelligence, interests, values, and needs and its program for general unification (Staats, 1963, pp. 304–308).

The point here is that PB’s broad-scope unification orientation has made it a different kind of behaviorism in various fundamental ways, including that of making it a behaviorism with a personality. The PB theory of personality is the only one that has been constructed on the foundation of a set of learning-behavior principles (Staats, 1996). Advancing in successive works, with different features than other personality theories, only in its later version has the theory of personality begun to arouse interest in the general field of behavior therapy. It appears that some behavior therapists are beginning to realize that behaviorists “have traditionally regarded personality, as a concept, of little use in describing and predicting behavior” (Hamburg, 2000, p. 62) and that this is a liability. Making that realization general, along with understanding how this weakens the field, is basic in effecting progress.

As it stands, behavior therapy’s rejection of the concept of personality underlies the field’s inability to join forces with the field of psychological measurement. This is anomalous because behavior therapists use psychological tests even while rejecting them conceptually. It is anomalous also because Kenneth Spence (1944), while not providing a conceptual framework for bringing behaviorism and psychological testing together, did provide a behavioral rationale for the utility of tests. He said that tests produce R-R (responseresponse) laws—in which a test score (one response) is used to predict some later performance (the later response). It needs to be added that tests can yield knowledge of behavior in addition to prediction as we will see.

This, then, is the state of affairs at present. Not one of the other behavioral approaches—radical behaviorism, Hullian theory, social learning theory, cognitive-behavioral theory— has produced or projected a program for the study of personality and its measurement. That is a central reason why traditional psychology is alienated from behaviorism and behavioral approaches. And that separation has seriously disadvantaged both behaviorism and traditional psychology.

The State of Theory in the Field of Personality

Thus far a critical look has been directed at the behaviorism positions with respect to the personality and psychological testing fields. This is not to say that those two fields are fulfilling their potential or are open to unification with any behavioral approach. Just as behaviorism has rejected personality and psychological measurement, so have the latter rejected behaviorism. Part of this occurs because traditional behaviorism does not develop some mutuality of interest, view, or product. But the fields of psychological testing and personality have had a tradition that considers genetic heredity as the real explanation of individual differences. Despite lip service to the contrary, these fields have never dealt with learning. So there is an ingrained mutual rejection. Furthermore, the lack of a learning approach has greatly weakened personality theory and measurement, substantively as well as methodologically, as I will suggest.

To continue, examination of the field of personology reveals it to be, at least within the present philosophy-methodology, a curiosity of science. For this is a field without guidelines, with no agreement on what its subject matter—personality—is and no concern about that lack of stipulation. It is accepted that there will be many definitions in the operating field. The only consensus, albeit implicit, is that personality is some process or structure within the individual that is a cause of the individual’s behavior. Concepts of personality range from the id, ego, and superego of Sigmund Freud, through the personal constructs of George Kelly and Carl Rogers’s life force that leads to the maintenance and enhancement of self, to Raymond B. Cattell’s source traits of sociability, intelligence, and ego strength, to mention a very few.

Moreover, there is no attempt to calibrate one concept of personality with respect to another. In textbooks each personality theory is described separately without relating concepts and principles toward creating some meaningful relationships. There are no criteria for evaluating the worth of the products of the field, for comparing them, for advancing the field as a part of science. Each author of a theory of personality is free to pursue her or his own goals, which can range from using factor analytic methods by which to establish relationships between test items and questionnaires to running pigeons on different schedules of reinforcement. There will be little criticism or evaluation of empirical methods or strategies.All is pretty much accepted as is.There will be no critical consideration of the kind of data that are employed and evaluation of what the type of data mean about the nature of the theory. Other than psychometric criteria of reliability and validity, there will be no standards of success concerning a test’s provision of understanding of the trait involved, what causes the trait, or how it can be changed. Also, the success of a personality theory will not be assessed by the extent to which it provides a foundation for constructing tests of personality, therapies, or procedures for parents to employ. It is also not necessary that a personality theory be linked to other fields of study.

Moreover, a theory in this field does not have the same types of characteristics or functions as do theories in the physical sciences. Those who consider themselves personality theorists are so named either because they have created one of the many personality theories or because they have studied and know about one or more of the various existent theories. They are not theorists in the sense that they work on the various personality theories in order to improve the theory level of the field. They are not theorists in the sense that they study their field and pick out its weaknesses and errors in order to advance the field. They do not analyze the concepts and principles in different theories in order to bring order into the chaos of unrelated knowledge. They do not, for example, work on the large task of weaving the theories together into one or more larger, more advanced, and more general and unified theories that can then be tested empirically and advanced.

An indication of the mixed-up character of the field of personality theory is the inclusion of Skinner’s experimental analysis of behavior as a personality theory in some textbooks on personality theory. This is anomalous because Skinner has rejected the concept of personality, has never treated the phenomena of personality, has had no program for doing so, and his program guides those who are radical behaviorists to ignore the fields of personality and its measurement. His findings concerning schedules of reinforcement are not used by personologists, nor are his students’findings using the experimental analysis of behavior with human subjects nor his philosophy-methodology of science. His approach appears to be quite irrelevant for the field. What does it say about the field’s understanding of theory that the irrelevance of his theory does not matter? From the standpoint of the philosophy and methodology of PB, the field of personality is in a very primitive state as a science.

To some extent the following sections put the cart before the horse because I discuss some theory needs of the field of personality before I describe the approach that projects those needs. That approach involves two aspects: a particular theory and a philosophy-methodology. The latter is the basis for the projections made in this section. This topic needs to be developed into a full-length treatment rather than the present abbreviation.

The Need for Theorists Who Work the Field

One of the things that reveals that the field of personality theory is not really part of a fully developed science is the lack of systematic treatment of the theories in the field. Many study the theories of the field and their empirical products. But that study treats the field as composed of different and independent bodies of knowledge to be learned. There is not even the level of integration of study that one would find in humanities, such as English literature and history, where there is much comparative evaluating of the characteristics of different authors’works.

If the field of personality theory is to become a real scientific study, we need theorists who work the field.Theories have certain characteristics. They contain concepts and principles, and the theories deal with or derive from certain empirical data. And those concepts, principles, and data vary in types and in functions. With those differences, theories differ in method and content and therefore in what they can do and thus how they fit together or not. We need theorists who study such things and provide knowledge concerning the makeup of our field. What can we know about the field without such analysis?

We need theorists who work the field in other ways also. For example, two scientific fields could be at the same level in terms of scientific methods and products. One field, however, could be broken up by having many different theorists, each of whom addresses limited phenomena and does so in idiosyncratic theory language, with no rules relating the many theories. This has resulted in competing theories, much overlap among theories and the phenomena they address, and much redundancy in concepts and principles mixed in with real differences. This yields an unorganized, divided body of knowledge. Accepting this state provides no impetus for cooperative work or for attaining generality and consensus.

The other hypothetical field has phenomena of equal complexity and difficulty, and it also began with the same unorganized growth of theory. But the field devoted part of its time and effort in working those theories, that is, in assessing what phenomena the various theories addressed, what their methods of study were, what types of principles and concepts were involved, and where there was redundancy and overlap, as well as in comparing, relating, and unifying the different theory-separated islands of knowledge.The terms for the concepts and principles were standardized, and idiosyncrasy was removed. The result was a simpler, coherent body of knowledge that was also more general. That allowed people who worked in the field to speak the same language and to do research and theory developments in that language in a way that everyone could understand. In turn, researchers could build on one another’s work. That simplifying consensus also enabled applied people to use the knowledge better.

It can be seen that although these two sciences are at the same level with respect to much of their product, they are quite different with respect to their theory advancement and operation. The differences in the advancement of knowledge in science areas along these lines have not been systematically considered in the philosophy of science. There has not been an understanding that the disunified sciences (e.g., psychology) operate differently than do the unified sciences (e.g., physics) that are employed as the models in the philosophy of science. Thus, there has been no guide for theorists to work the fields of personality theory and psychological testing to produce the more advanced type of knowledge. So this remains a crying need.

We Need Theory Constructed in Certain Ways and With Certain Qualities and Data

We need theorists to work the field of personality. And they need to address certain tasks, as exemplified earlier and later. This is only a sample; other characteristics of theory also need to be considered in this large task.

Commonalities Among Theories

In the field of personality theory there is much commonality, overlap, and redundancy among theories. This goes unrecognized, however, because theorists are free to concoct their own idiosyncratic theory language. The same or related phenomena can be given different names—such as ego, self, selfconcept, and self-efficacy—and left alone as different. Just in terms of parsimony (an important goal of science), each case of multiple concepts and unrecognized full or partial redundancy means that the science is unnecessarily complex and difficult, making it more difficult to learn and use. Unrecognized commonality also artificially divides up the science, separating efforts that are really relevant. Personality theorists, who are in a disunified science in which novelty is the only recognized value, make their works as different as possible from those of others. The result is a divided field, lacking methods of unification.

We need theorists who work to remove unnecessary theory elements from our body of knowledge, to work for simplicity and standardization in theory language. We need to develop concepts and principles that everyone recognizes in order to build consistency and consensus. It is essential also for profundity; when basic terms no longer need to be argued, work can progress to deeper levels.

Data of Theories and Type of Knowledge Yielded

A fundamental characteristic of the various theories in personality is that despite overlap they address different sets of phenomena and their methods of data collection are different. For example, Freud’s theory was drawn to a large extent from personal experience and from the stated experiences of his patients. Carl Rogers’s data was also drawn from personal experience and clinical practice. Gordon Allport employed the lexical approach, which involved selecting all the words from a dictionary that descriptively labeled different types of human behavior. The list of descriptive words was whittled down by using certain criteria and then was organized into categories, taken to describe traits of personality. This methodology rests on large numbers of people, with lay knowledge, having discriminated and labeled different characteristic behaviors of humans. Raymond Cattell used three sources of data. One consisted of life records, as in school or work. Another source was self-report in an interview. And a third could come from objective tests on which the individual’s responses could be compared to the responses of others. These data could be subjected to factor analytic methods to yield groupings of items to measure personality traits.

What is not considered systematically to inform us about the field is that the different types of data used in theories give those theories different characteristics and qualities. To illustrate, a theory built only on the evanescent and imprecise data of personal and psychotherapy experience—limited by the observer’s own concepts and flavored by them—is unlikely to involve precisely stated principles and concepts and findings. Moreover, any attempt by the client to explain her behavior on the basis of her life experience is limited by her own knowledge of behavior and learning and perhaps by the therapist’s interpretations. The naturalistic data of selfdescription, however, can address complex events (e.g., childhood experiences) not considered in the same way in an experimental setup. Test-item data, as another type, can stipulate behaviors while not including a therapist’s interpretations. However, such items concern how individuals are, not how they got that way (as through learning).

Let us take as an example an intelligence test. It can predict children’s performance in school. The test was constructed to do this. But test data do not tell us how “intelligence” comes about or what to do to increase the child’s intelligence. For in constructing the test there has been no study of the causes of intelligence or of how to manipulate those causes to change intelligence. The theory of intelligence, then, is limited by the data used. Generally, because of the data on which they rest, tests provide predictive variables but not explanatory, causal variables. Not understanding this leads to various errors.

The data employed in some theories can be of a causal nature, but not in other theories. Although data on animal conditioning may lack other qualities, it does deal with causeeffect principles. Another important aspect of data used involves breadth. How many different types of data does a theory draw on or stimulate? From how many different fields of psychology does the theory draw its data? We should assess and compare theories on the types of data on which they are based. Through an analysis of types of data we will have deeper knowledge of our theories, how they differ, how they are complementary, the extent to which they can be developed to be explanatory as well as predictive, and also how they can or cannot be combined in organizing and unifying our knowledge.

Precision of Theories

There are also formal differences in theories in terms of other science criteria, for example, in the extent of precision of statement. A known example of imprecision was that of Freud’s reaction formation. If the person did not do as predicted, then the reaction formation still allowed the theory always to be “right.” Another type of difference lies in the precision or vagueness of definition of concepts. Hull aimed to define his habit strength concept with great precision. Rogers’s concept of the life force does not have such a precise definition. Science is ordinarily known for its interest in considering and assessing its theory tools with respect to such characteristics. The field of personality needs to consider its theories in this respect.

Unifying and Generality Properties of Theories

Hans Eysenck showed an interest in applications of conditioning principles to problems of human behavior. He also worked on the measurement of personality, in traits such as intelligence and extroversion-introversion. Moreover, he also had interest in variations in psychic ability as shown in experiments in psychokinisis. (During a six-month stay at the Maudsley Hospital in 1961, the author conveyed the spread of our American behavioral applications and also argued about psychic phenomena, taking the position that selecting subjects with high “psychic” ability abrogated the assumptions for the statistics employed.) Theorists vary in the number of different research areas to which they address themselves. And that constitutes an important dimension; other things equal, more general theories are more valuable than narrow theories.

Another property of a theory is that of unifying power. The example of Eysenck can be used again. That is, although he was interested in behavior therapy, personality measurement, and experimental psychic ability, he did not construct a theory within which these phenomenal areas were unified within a tightly reasoned set of interrelated principles. Both the generality and the unifying power of theories are very important.

Freud’s psychological theory was more general than Rogers’s. For example, it pertains to child development, abnormal psychology, and clinical psychology and has been used widely in those and other fields. And Freud’s theory— much more than other theories that arise in psychotherapy— also was high in the goal of unification. John Watson began behaviorism as a general approach to psychology. The behavioral theories of personality (such as that of Rotter, and to some extent the other social learning theories) exhibit some generality and unification. The present theory, PB, has the most generality and unification aims of all. None of the personality theories, with the exception of the present one, moreover, has a systematic program for advancing further in generality and unification.

In general, there are no demands in the field of personality to be systematic with respect to generality or unification, and there are no attempts to evaluate theories for success in attaining those goals. Again, that is different from the other more advanced, unified sciences. That is unfortunate, for the more a theory of personality has meaning for the different areas of psychology, employs products of those fields, and has implications for those fields, the more valuable that theory can be.

This view of the field of personality and its personality theories is a byproduct of the construction of the theory that will be considered in the remaining sections. The perspective suggests that the field of personality will continue to stagnate until it begins to work its contents along the lines proposed.

Personality: The Psychological Behaviorism Theory

More than 45 years ago, while still a graduate student at UCLA, I began a research program that for some years I did not name, then called social behaviorism, later paradigmatic behaviorism, and finally PB. I saw great importance in the behaviorism tradition as a science, in fundamental learning principles, and in experimentation. But I saw also that the preceding behaviorisms were incompletely developed, animal oriented, and too restricted to laboratory research. They also contained fundamental errors and had no plan by which to connect to traditional psychology, to contribute to it, and to use its products. Very early in the research program I began to realize that animal conditioning principles are not sufficient to account for human behavior and personality. In my opinion a new behavioral theory was needed, it had to focus on human behavior systematically and broadly, it had to link with traditional psychology’s treatments of many phenomena of human behavior, and it had to include a new philosophy and methodology.

Basic Developments

The early years of this program consisted of studies to extend, generally and systematically, conditioning principles to samples of human behavior. This was a new program in behaviorism. Some of the studies were informal, some were formal publications, and many involved theoretical analyses of behaviors—experimental, clinical, and naturalistic—that had been described in the psychology literature. One of the goals was to advance progressively on the dimension of simplecomplex with respect to behavior. The low end of the dimension involved establishment of basic principles, already begun with the animal conditioning principles. But those principles had to be verified with humans, first with simple behaviors and laboratory control. Then more and more complex behaviors had to be confronted, with the samples of behavior treated becoming more representative of life behaviors. The beginning of this latter work showed convincingly the relevance of learning-behavior principles for understanding human behavior and progressively indicated that new human learning principles were needed to deal with complex human behavior. Several areas of PB research are described here as historical background and, especially, to indicate how the theory of personality arose in an extended research-conceptual development.

Language-Cognitive Studies

My dissertation studied how subjects’ verbal responses to problem-solving objects were related to the speed with which they solved the problem. It appeared that people learn many word labels to the objects and events of life. When a situation arises that involves those objects and events, the verbal responses to them that individuals have learned will affect their behavior. The research supported that analysis.

There are various kinds of labeling responses. A child’s naming the letters of the alphabet involves a labeling repertoire. Studies have shown that children straightforwardly learn such a repertoire, as they do in reading numbers and words. The verbal-labeling repertoire is composed of various types of spoken words controlled by stimulus events. The child learns to say “car” to cars as stimulus events, to say “red” to the stimulus of red light, to say “running” to the visual stimulus of rapidly alternating legs that produce rapid movement, and to say “merrily” to people happily reveling. Moreover, the child learns these verbal labeling responses—like the nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs just exemplified—in large quantities, so the verbal-labeling repertoire becomes huge. This repertoire enables the person to describe the many things experienced in life, but it has other functions as well. As discussed later, this and the other language repertoires are important components of intelligence.

As another aspect of language, the child also learns to make different motor responses to a large number of words. The young child learns to look when hearing the word “look,” to approach when hearing the word “come,” to sit when told the word “sit,” and to make a touching response when told to “touch” something. The child will learn to respond to many words with motor responses, constituting the verbal-motor repertoire. This repertoire enables the person to follow directions. It is constituted not only of a large number of verbs, but also of adverbs, nouns, adjectives, and other grammatical elements. For example, most people could respond appropriately to the request to “Go quickly, please, to the top-left drawer of my dresser and bring me the car keys” because they have learned motor responses to the relevant words involved. Important human skills involve special developments of the verbal-motor subrepertoire. As examples, ballet dancers, violinists, NFL quarterbacks, mechanics, and surgeons have special verbal-motor repertoires that are essential parts of their special skills.

Another important part of language is the verbalassociation repertoire. When the word salt is presented as a stimulus in a word-association task, a common response is pepper or water. However, an occasional person might respond by saying wound or of the earth or something else that is less usual. Years ago it was believed that differences in associations had personality implications, and word-association tests were given with diagnostic intent. Analysis of word associations as one of the subrepertoires of the language-cognitive repertoire suggests more definitively and specifically that this constitutes a part of personality. Consider a study by Judson, Cofer, and Gelfand (1956). One group of subjects learned a list of words that included the sequence rope, swing, and pendulum. The other group learned the same list of words, but the three words were not learned in sequence. Both groups then had to solve a problem by constructing a pendulum from a light rope and swinging it. The first group solved the problem more quickly than did the second. Thus, in the present view the reasoning ability of the two groups depended on the word associations they had learned.

Word associates are central to our grammatical speech, the logic of our speech and thought, our arithmetic and mathematical knowledge, our special area and general knowledge, our reasoning ability, our humor, our conversational ability, and our intelligence. Moreover, there are great individual differences in the verbal-association repertoire such that it contributes to differences on psychological tests. Additional repertoires are described in the PB theory of languagecognition (see Staats, 1968, 1971, 1975, 1996).

Emotional-Motivational Studies

An early research interest of PB concerned the emotional property of words. Using my language conditioning method I showed subjects a visually presented neutral word (nonsense syllable) paired once each with different auditorily presented words, each of which elicited an emotional response, with one group positive emotion and with another group negative in a classical conditioning procedure. The results of a series of experiments have showed that a stimulus paired with positive or negative emotional words acquires positive or negative emotional properties. Social attitudes, as one example, are emotional responses to people that can be manipulated by language conditioning (Staats & Staats, 1958). To illustrate, in a political campaign the attempt is made to pair one’s candidate with positive emotional words and one’s opponent with negative emotional words. That is why the candidate with greater financial backing can condition the audience more widely, giving great advantage.

Skinner’s theory is that emotion (and classical conditioning) and behavior (and operant conditioning) are quite separate, and it is the operant behavior that is what he considers important. In contrast, PB’s basic learning-behavior theory states that the two types of conditioning are intimately related and that both are important to behavior. For one thing, a stimulus is reinforcing because it elicits an emotional response. Thus, as a stimulus comes to elicit an emotional response through classical conditioning, it gains potential as a reinforcing stimulus. My students and I have shown that words eliciting a positive or negative emotional response will function as a positive or negative reinforcer. In addition, the PB learning-behavior theory has shown that a stimulus that elicits a positive or negative emotional response will also function as a positive or negative incentive and elicit approach or avoidance behavior. That is a reason why emotional words (language) guide people’s behavior so ubiquitously. An important concept from this work is that humans learn a very large repertoire of emotion-eliciting words, the verbalemotional repertoire. Individual differences in this repertoire widely affect individual differences in behavior (see Staats, 1996).

One other principle should be added for positive emotional stimuli: They are subject to motivational (deprivationsatiation) variations. For example, food is a stimulus that elicits a positive emotional response on a biological basis; however, the size of the response varies according to the extent of food deprivation. That also holds for the reinforcement and incentive effect of food stimuli on operant behavior. These three effects occur with stimuli that elicit an emotional response through biology (as with food) or through learning, as with a food word.

The human being has an absolutely gargantuan capacity for learning. And the human being has a hugely complex learning experience. The result is that in addition to biologically determined emotional stimuli, the human learns a gigantic repertoire that consists of stimuli that elicit an emotional response, whether positive or negative. There are many varieties of stimuli—art, music, cinema, sports, recreations, religious, political, manners, dress, and jewelry stimuli—that are operative for humans. They elicit emotion on a learned basis. As a consequence, they can also serve as motivational stimuli and act as reinforcers and incentives. That leads to a conclusion that individual differences in the quantity and type of emotional stimuli will have great significance for personality and human behavior.

Sensorimotor Studies

Following its human-centered learning approach, PB studied sensorimotor repertoires in children. To illustrate, consider the sensorimotor response of speech. Traditional developmental norms state that a child generally says her first words at the age of 1 year, but why there are great individual differences is not explained, other than conjecturing that this depends on biological maturation processes. In contrast, PB states that speech responses are learned according to reinforcement principles, but that reinforcement depends on prior classical conditioning of positive emotion to speech sounds (Staats, 1968, 1996). I employed this theoretical analysis and learning procedures in accelerating the language development of my own children, in naturalistic interactions spread over a period of months, but adding up to little time expenditure. Their speech development accelerated by three months, which is 25% of the usual 12-month period (Staats, 1968). I have since validated the learning procedures with parents of children with retarded speech development. Lovaas (1977) has used this PB framework. Psychological behaviorism also systematically studied sensorimotor skills such as standing, walking, throwing and catching a ball, using the toilet, writing letters, paying attention, counting objects, and so on in systematic experimentallongitudinal research (see Staats, 1968, 1996).

In this theory of child development, PB pursued its goal of unification with traditional psychology, in this case with the field of child development. The PB position is that the norms of traditional child developmentalists provide valuable knowledge. But this developmental conception errs in assuming biological determination and in ignoring learning. Prior to my work, the reigning view was that it was wasteful or harmful to attempt to train the child to develop behaviors early. For example, the 4-year-old child was said to be developmentally limited to an attention span of 5 min to 15 min and thus to be incapable of formal learning. We showed that such preschoolers can attend well in the formal learning of reading skills for 40-min periods if their work behaviors are reinforced (Staats et al., 1964). When not reinforced, however, they do not attend. My later research showed that children learn progressively to attend and work well for longer periods by having been reinforced for doing so.

Rather than being a biologically determined cognitive ability, attention span is actually a learned behavior. The same is true with the infant’s standing and walking, the development of both of which can be advanced by a little systematic training. The child of 2 years also can be straightforwardly trained to count unarranged objects (Piaget said 6 years). Writing training can be introduced early and successfully, as can other parts of the sensorimotor repertoire. I also developed a procedure for potty training my children (see Staats, 1963) that was later elaborated byAzrin and Foxx (1974). Such findings have changed society’s view of child development.

What emerges from this work is that the individual learns the sensorimotor repertoire. Without the learning provided in the previous cases, children do not develop the repertoires. Moreover, the human sensorimotor repertoire is, again, vast for individuals. And over the human community it is infinitely varied and variable. There are skills that are generally learned by all, such as walking and running. And there are skills that are learned by only few, such as playing a violin, doing surgery, or acting as an NFLquarterback. As such there are vast individual differences among people in what sensorimotor skills are learned as well as in what virtuosity.

Additional Concepts and Principles

Human Learning Principles

As indicated earlier, a basic assumption of traditional behaviorism is that the animal learning principles are the necessary and sufficient principles for explaining human behavior. Psychological behaviorism’s program has led to the position that while the animal conditioning principles, inherited through evolution, are indeed necessary for explaining human behavior, they are far from sufficient. I gained an early indication of that with my research on the language conditioning of attitudes, and later findings deepened and elaborated the principles.

What the traditional behaviorists did not realize is that human learning also involves principles that are unique to humans—human learning principles. The essential, new feature of these principles is that much of what humans learn takes place on the basis of what they have learned before. For example, much human learning can occur only if the individual has first learned language. Take two children, one of whom has learned a good verbal-motor repertoire and one of whom has not. The first child will be able to follow directions and therefore will be able to learn many things the second child cannot because many learning tasks require the following of directions. The goodness of that verbal-motor repertoire distinguishes children (as we can see on any intelligence test for children). In PB, language is considered a large repertoire with many important learning functions. Learning to count, to write, to read, to go potty, to form attitudes, to have logic and history and science knowledge and opinions and beliefs, to be religious, to eat healthily and exercise, and to have political positions are additional examples in which language is a foundation.Achild of 18 months can easily learn to name numbers of objects and then to count if that child has previously learned a good language repertoire (see Staats, 1968). On the other hand, a child of 3 years who has not learned language will not be able to learn those number skills. The reason for the difference is not some genetic difference in the goodness of learning. Rather, the number learning of the child is built on the child’s previous language learning. It is not age (biology) that matters in the child’s learning prowess; it is what the child has already learned.

Cumulative-Hierarchical Learning

Human learning is different from basic conditioning because it typically involves learning that is based on repertoires that have been previously learned. This is called cumulativehierarchical learning because of the building properties involved—the second learning is built on the first learning but, in turn, provides the foundation for a third learning. Multiple levels of learning are typical when a fine performance is involved. Let us take the learning of the language repertoire. When the child has a language repertoire, the child can then learn to read. When the child has a reading repertoire, the child can learn more advanced number operations, after which the child can learn an algebra repertoire, which then is basic in learning additional mathematics repertoires, which in turn enable the learning of physics. Becoming a physicist ordinarily will involve in excess of 20 years of cumulative-hierarchical learning.

Cumulative-hierarchical learning is involved in all the individual’s complex characteristics. A sociopath—with the complex of language-cognitive, emotional-motivational, and sensorimotor repertoires this entails—does not spring forth full-blown any more than being a physicist. Understanding the sociopathic personality, hence, requires understanding the cumulative-hierarchical learning of the multiple repertoires that have been involved.

The Basic Behavioral Repertoire: A Cause as Well as an Effect

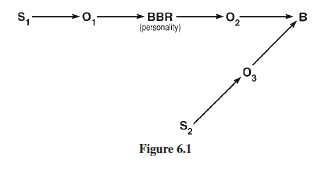

And that brings us to another concept developed in PB, that is, the basic behavioral repertoire (BBR). The BBRs are those repertoires that provide the means by which later learning can occur, in the cumulative-hierarchical learning process. In providing foundations for further learning, the three major BBRs—the emotional-motivational, language-cognitive, and sensorimotor—also grow and elaborate through cumulative-hierarchical learning.

The learning of the basic behavioral repertoires changes the individual. The BBRs thus act as independent variables that determine what the individual experiences, how the individual behaves, and what the individual learns. The cumulative-hierarchical learning of such repertoires is fundamental in child development; in fact, the PB theory is that the study of that learning should be the primary objective of this field, as it should be in the field of personality.

The Concept of Personality

It is significant in comparing the PB theory to other personality theories to note differences in such things as the type of data involved and the specificity, precision, systematicity, and empirical definition of principles and concepts. It is such characteristics that determine the functions that a theory can have. Another characteristic of the PB approach concerns the schism between traditional psychology and traditional behaviorism. Traditional psychology infers personality as a unique internal process or structure that determines the individual’s unique behavior. That makes study of personality (and related concepts) very central. Traditional behaviorism, in opposition, and according to its fundamental methodology, cannot accept an inferred concept as the cause of behavior. So, while almost every personologist considers learning to be important in personality, traditional behaviorism, which should be concerned with how learning affects personality, cannot even consider the topic. The schism leaves personality theories incomplete and divides psychology.

The PB Definition of Personality

The PB program has led to the development of a theory of personality that can resolve that schism in a way that is valuable to both sides. The PB definition of personality is that it is composed of the three basic behavioral repertoires that the individual has learned. That definition harmonizes with behaviorism, for the PB program is to study the behaviors in those repertoires and how they are learned, as well as how they have their effects on the individual’s characteristic behavior. At the same time, that definition is very compatible with the traditional view of personality as an internal process or structure that determines behavior. As such, the PB concept of personality can link with traditional work on personality, including personality tests, and can also contribute to advancement of that work. How the three BBRs compose personality is described next.

The Emotional-Motivational Aspects of Personality

There are many concepts that refer to human emotions, emotional states, and emotional personality traits.As examples, it may be said that humans may feel the responses of joy or fear, may be in a depressed or euphoric state, and may be optimistic or pessimistic as traits. The three different emotional processes are not usually well defined. PB makes explicit definitions. First, the individual can experience specific, ephemeralemotionalresponsesdependingontheappearancecessation of a stimulus. Second, multiple emotion-eliciting events can yield a series of related emotional responses that add together and continue over time; this constitutes an emotional state. Third, the individual can learn emotional responses to sets of stimuli that are organized—like learning a positive emotional response to a wide number of religious stimuli. That constitutes an emotional-motivational trait (religious values); that is, the individual will have positive emotional responses to the stimuli in the many religious situations encountered.And that emotional-motivational trait will affect the individual’s behavior in those many situations (from the reinforcer and incentive effects of the religious stimuli). For these reasons the trait has generality and continuity. There are psychological tests for traits such as interests, values, attitudes, and paranoid personality. There are also tests for states such as anxiety and depression and moods. And there are also tests for single emotional responses, such as phobias or attitudes.

Personality theories usually consider emotion. This is done in idiosyncratic terminology and principles. So how one theory considers emotion is not related to another. Theories of emotion at the personality level are not connected to studies of emotion at more basic levels. Many psychological tests measure emotions, but they are not related to one another. Psychological behaviorism provides a systematic framework theory of emotion that can deal with the various emotional phenomena, analyze many findings within the same set of concepts and principles, and thus serve as a unifying overarching theory. Psychological behaviorism experimentation has shown that interest tests deal with emotional responses to occupation-related stimuli, that attitude tests deal with emotional responses to groups of people, and that values tests deal with emotional responses to yet other stimuli, unifying them in the same theory.

In the PB theory, beginning with the basic, the individual has emotional responses to stimuli because of biological structure, such as a positive emotional response to food stimuli, certain tactile stimuli, warm stimulation when cold, and vice versa, and a negative emotional response to aversive, harmful stimuli of various kinds. Conditioning occurs when any neutral stimulus is paired with one of those biological stimuli and comes to elicit the same type of emotional response. Conditioning occurs also when a neutral stimulus is paired with an emotion-eliciting stimulus (e.g., an emotional word) that has gained this property through learning. The human has a long life full of highly variable, complex experiences and learns an exceedingly complex emotional-motivational repertoire that is an important part of personality. People very widely have different emotional learning. Not everyone experiences positive emotional responses paired with religious stimuli, football-related stimuli, or sex-related stimuli. And different conditioning experiences will produce different emotionalmotivational repertoires. Because human experience is so variegated, with huge differences, everyone’s hugely complex emotional-motivational personality characteristics are unique and different.

That means, of course, that people find different things reinforcing. What is a reward for one will be a punishment for someone else. Therefore, people placed in the same situation, with the same reinforcer setup, will learn different things. Consider a teacher who compliments two children for working hard. For one child the compliment is a positive reinforcer, but for the other child it is aversive. With the same treatment one child will learn to work hard as a consequence, whereas the other will work less hard. That is also true with respect to incentives. If one pupil has a positive emotional response to academic awards and another pupil does not, then the initiation of an award for number of books read in one semester will elicit strong reading behavior in the one but not in the other. What is reinforcing for people and what has an incentive effect for them strongly affects how they will behave. That is why the emotional BBR is an important personality cause of behavior.

The Language-Cognitive Aspects of Personality

Each human normally learns a huge and fantastically complex language repertoire that reflects the hugely complex experience each human has. There is commonality in that experience across individuals, which is why we speak the same language and can communicate. But there are gigantic individual differences as well (although research on language does not deal with those). Those differences play a central role in the individual differences we consider in the fields of personality and personality measurement.

To illustrate, let us take intelligence as an aspect of personality. In PB theory intelligence is composed of basic behavioral repertoires, largely of a language-cognitive nature but including important sensorimotor elements also. People differ in intelligence not because of some biological quality, but because of the basic behavioral repertoires that they have learned. We can see what is specifically involved at the younger age levels, where the repertoires are relatively simple. Most items, for example, measure the child’s verbal-motor repertoire, as in following instructions. Some items specifically test that repertoire, as do the items on the Stanford-Binet (Terman & Merrill, 1937, p. 77) that instruct the child to “Give me the kitty [from a group of small objects]” and to “Put the spoon in the cup.” Such items, which advance in complexity by age, also test the child’s verbal-labeling repertoire. The child can only follow instructions and be “intelligent” if he or she has learned the names of the things involved.

The language-cognitive repertoires also constitute other aspects of personality, for they are important on tests of language ability, cognitive ability, cognitive styles, readiness, learning aptitude, conceptual ability, verbal reasoning, scholastic aptitude, and academic achievement tests. The tests, considered to measure different facets of personality, actually measure characteristics of the language-cognitive BBR. The self-concept also heavily involves the verbal-labeling repertoire, that is, the labels learned to the individual’s own physical and behavioral stimuli. People differ in the labels they learn and in the emotional responses elicited by those verbal labels. We can exemplify this using an item on the MMPI (Dahlstrom & Welsh, 1960, p. 57): “I have several times given up doing a thing because I thought too little of my ability.” Individuals who have had different experience with themselves will have learned different labels to themselves (as complex stimuli) and will answer the item differently. The self-concept (composed of learned words) is an important aspect of personality because the individual reasons, plans, and decides depending on those words. So the learned self-concept plays the role of a cause of behavior. As another example, the “suspiciousness” of paranoid personality disorder heavily involves the learned verballabeling repertoire. This type of person labels the behaviors of others negatively in an atypical way. The problem is that the unrealistic labeling affects the person’s reasoning and behavior in ways that are not adjustive either for the individual or for others.

These examples indicate that what are traditionally considered to be parts of personality are conceived of in PB as parts of the learned language-cognitive BBR.

The Sensorimotor Aspects of Personality

Traditionally, the individual’s behavior is not considered as a part of personality. Behavior is unimportant for the personologist. Everyone has the ability to behave. It is personality that is important, for personality determines behavior. Even when exceptional sensorimotor differences are clearly the focus of attention, as with superb athletes or virtuoso musicians, we explain the behavior with personality terms such as “natural athlete” or “talent” or “genius” each of which explains nothing.

Psychological behaviorism, in contrast, considers sensorimotor repertoires to constitute learned personality traits in whole or part. And there are very large individual differences in such sensorimotor repertoires. Part of being a physically aggressive person, for example, involves sensorimotor behaviors for being physically aggressive. Being a natural athlete, as another example, involves a complex set of sensorimotor skills (although different body types can be better suited for different actions). Being dependent, as another example, may also involve general deficits in behavior skills. Moreover, sensorimotor repertoires impact on the other two personality repertoires. For example, a person recognized for sensorimotor excellence in an important field will display language-cognitive and emotional-motivational characteristics of “confidence” that have been gained from that recognition.

A good example of how sensorimotor repertoires are part of personality occurred in a study by Staats and Burns (1981). The Mazes and Geometric Design tests of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI) (Wechsler, 1967) were analyzed into sensorimotor repertoire elements. That analysis showed that children learn that repertoire—of complex visual discrimination and other sensorimotor skills—when exposed to learning to write the letters of the alphabet. The expectation, thus, is that children trained to write letters will thereby acquire the repertoire by which to be “intelligent” on the Mazes and Geometric Design tests, as confirmed in our study. As other examples, on the Stanford-Binet (Terman & Merrill, 1937) the child has to build a block tower, complete a line drawing of a man, discriminate forms, tie a knot, trace a maze, fold and cut a paper a certain way, string beads a certain way, and so on. These all require that the child have the necessary sensorimotor basic behavioral repertoire. This repertoire is also measured on developmental tests. This commonality shows that tests considered measures of different aspects of personality actually measure the same BBR. Such an integrative analysis would be central in conceptualizing the field and the field needs many such analyses.

The sensorimotor repertoire also determines the individual’s experiences in ways that produce various aspects of personality. For example, the male who acquires the skills of a balletdancer,painter,carpenter,centerintheNBA,symphony violinist, auto mechanic, hair dresser, professional boxer, architect, or opera singer will in the learning and practice of those skills have experiences that will have a marked affect on his other personality repertoires. Much emotional-motivational and language-cognitive learning will take place, and each occupational grouping will as a result have certain common characteristics.