View sample positive human development research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The latter part of the twentieth century was marked by public anxiety about a myriad of social problems—some old, some new, but all affecting the lives of vulnerable children, adolescents, adults, families, and communities (Fisher & Murray, 1996; R. M. Lerner & Galambos, 1998; R. M. Lerner, Sparks, & McCubbin, 1999). In America, for instance, a set of problems of historically unprecedented scope and severity involved interrelated issues of economic development, environmental quality, health and health care delivery, poverty, crime, violence, drug and alcohol use and abuse, unsafe sex, and school failure.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Indeed, in the latter portion of the twentieth century and into the present one, and across the United States and in other nations, infants, children, adolescents, and the adults who care for them continued to die from the effects of these social problems (Dryfoos, 1990; Hamburg, 1992; Hernandez, 1993; Huston, 1991; R. M. Lerner, 1995; Schorr, 1988, 1997). If people were not dying, their prospects for future success were being reduced by civil unrest and ethnic conflict, by famine, by environmental challenges (e.g., involving water quality and solid waste management), by school underachievement and dropout, by teenage pregnancy and parenting, by lack of job opportunities and preparedness, by prolonged welfare dependency, by challenges to their health (e.g., lack of immunization, inadequate screening for disabilities, insufficient prenatal care, and lack of sufficient infant and childhood medical services), and by the sequelae of persistent and pervasive poverty (Huston, McLoyd, & Garcia Coll, 1994; R. M. Lerner & Fisher, 1994). These issues challenge the resources and the future viability of civil society in America and throughout the world (R. M. Lerner, Fisher, & Weinberg, 2000a, 2000b).

The potential role of scientific knowledge about human development in addressing these issues of individuals, families, communities, and civil society resulted in growing interest and activity in what has been termed applied developmental science (ADS). Scholars such as Celia B. Fisher (Fisher & Lerner, 1994; Fisher et al., 1993), Richard A. Weinberg (e.g., R. M. Lerner, Fisher, & Weinberg, 1997, 2000a, 2000b), Lonnie R. Sherrod (e.g., 1999a, 1999b), Jacquelynne Eccles (Eccles, Lord, & Buchanan, 1996), Ruby Takanishi (1993), and Richard M. Lerner (1998b, 2002a, 2002b) specify thatADS is scholarship that is predicated on a developmental systems theoretical perspective. This theoretical approach sees the multiple levels of organizations involved in human development—including biology, psychology, social relations, group/institutions, culture, physical environment, and history—as existing in an integrated, fused system. The perspective stresses that relations among components of the system are the appropriate units of developmental analysis (R. M. Lerner, 1998b, 2002a). This approach also views individuals as active producers of their own development through the relationships they have with their contexts (R. M. Lerner, 1982; R. M. Lerner & Walls, 1999). Given that development occurs through the changing relations that individuals have with their contexts, there is an opportunity for plasticity, for systematically changing the course of human development by altering the trajectory of these relations (Fisher & Lerner, 1994).

Consistent with its emphasis on integrated systems, ADS seeks to synthesize developmental research with community outreach in order to describe, explain, and enhance the life chances of vulnerable children, adolescents, young and old adults, and their families across the life span (Fisher & Lerner, 1994). Given its roots in developmental systems theory, ADS challenges the usefulness of decontextualized knowledge and, as a consequence, the legitimacy of isolating scholarship from the pressing human problems of our world.

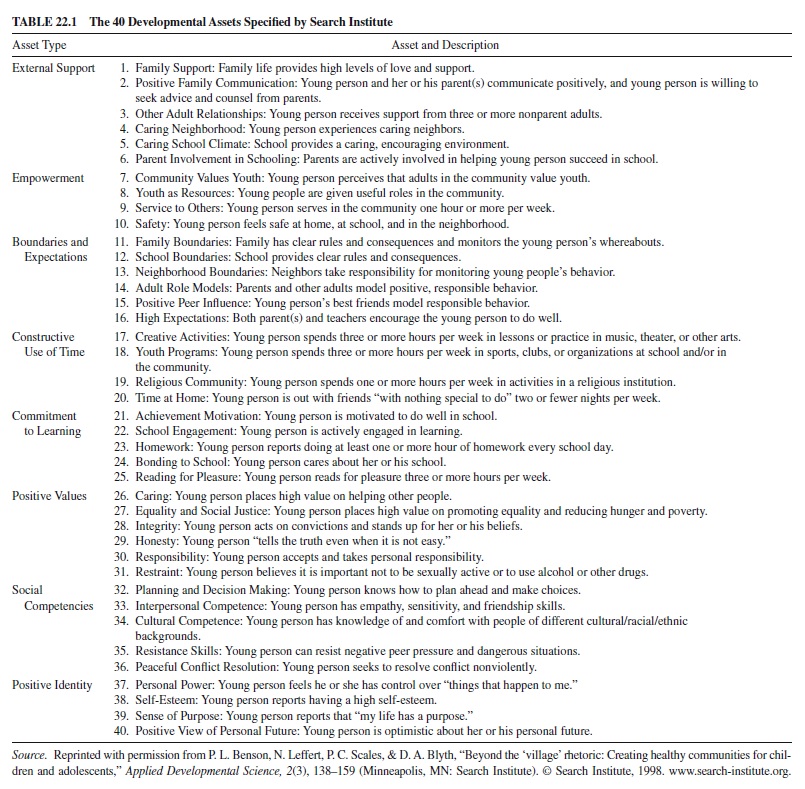

In this research paper we discuss key facets of the theoretical bases for the integrated approach taken byADS to knowledge generation and knowledge application. We emphasize the central role of fused relations between individuals and contexts (or, more generally, among levels of organization in the developmental system) in the theoretical and empirical work legitimating theADS approach to knowledge. To advance our argument we first review the key conceptual principles associated with ADS and the relational foci of ADS scholarship. We emphasize the synthetic view of basic, explanatory research and applied research that is brought to the fore by the developmental systems thinking that framesADS, and we explain why person-context relations constitute the core focus of research designed to study the basic process of human development envisioned within ADS. Several lines of research that model such person-context relations are reviewed, including those associated with the goodness-of-fit model (e.g., Chess & Thomas, 1999), the stage-environment fit model (e.g., Eccles, Midgley, et al., 1993), and models integrating individual and community assets in the promotion of positive youth development (Benson, 1997; Damon, 1997).

The Principles of Applied Developmental Science

Fisher and her colleagues (Fisher et al., 1993) delineated five conceptual components that characterize the principles or core substantive features of ADS. Taken together, these conceptual features make ADS a unique approach to understanding and promoting positive development.

The first conceptual component of ADS is the notion of the temporality, or historical embeddedness, of change pertinent to individuals, families, institutions, and communities. Some components of the context or of individuals remain stable over time, and other components may change historically. Because phenomena of human behavior and development vary historically, one must assess whether generalizations across time periods are legitimate. Thus, temporality has important implications for research design, service provision, and program evaluation.

Interventions are aimed at altering the developmental trajectory of within-person changes. To accomplish this aim, the second conceptual feature of ADS is that applied developmental scientists take into account interindividual differences (diversity) among, for instance, racial, ethnic, social class, and gender groups, as well as intra-individual changes, such as those associated with puberty.

The third conceptual feature of ADS places an emphasis on the centrality of context. There is a focus on the relations among all levels of organization within the ecology of human development. These levels involve biology, families, peer groups, schools, businesses, neighborhoods and communities, physical-ecological settings, and the sociocultural, political, legal-moral, and economic institutions of society. Together, bidirectional relations among these levels of the developmental system necessitate systemic approaches to research, program and policy design, and program and policy implementation.

The fourth principle of ADS emphasizes descriptively normative developmental processes and primary prevention and optimization rather than remediation. Applied developmental scientists emphasize healthy and normative developmental processes and seek to identify the strengths and assets of individual groups and settings, rather than focusing on deficits, weaknesses, or problems of individuals, families, or communities. Instead of dwelling on the problems faced by people, applied developmental scientists aim to find combinations of individual and ecological assets associated with thriving among people (e.g., Benson, 1997; Benson, Leffert, Scales, & Blyth, 1998; Leffert et al., 1998; Scales, Benson, Leffert, & Blyth, 2000) and with the five Cs of positive individual development: competence, confidence, connection, character, and caring/compassion (Hamilton & Hamilton, 1999; R. M. Lerner, 2002b; Little, 1993; Pittman, 1996).

The final principle of ADS is the appreciation of the bidirectional relationship between knowledge generation and knowledge application. By acknowledging bidirectionality, applied developmental scientists recognize the importance of knowledge about life and development that exists among the individuals, families, and communities being served by ADS. For applied developmental scientists, collaboration and colearning between researchers/universities and communities are essential features of the scholarly enterprise (R. M. Lerner, 1998a, 1998b). Such community-collaborative efforts are termed outreach scholarship (R. M. Lerner & Miller, 1998).

In other words, given the developmental systems perspective that ADS is predicated on, applied developmental scientists assume that

there is an interactive relationship between science and application. Accordingly, the work of those who generate empirically based knowledge about development and those who provide professional services or construct policies affecting individuals and families is seen as reciprocal in that research and theory guide intervention strategies and the evaluation of interventions and policies provides the bases for reformulating theory and future research… Asa result,applieddevelopmental[scientists] notonly disseminate information about development to parents, professionals, and policy makers working to enhance the development of others, they also integrate the perspectives and experiences of these members of the community into the reformulation of theory and the design of research and interventions. (Fisher & Lerner, 1994, p. 7)

Foci of Applied Developmental Science

The National Task Force on Applied Developmental Science (Fisher et al., 1993) indicated that the activities of ADS span a continuum from knowledge generation to knowledge application. These activities include, but are not limited to, research on the applicability of scientific theory to growth and development in natural, ecologically valid contexts; the study of developmental correlates of phenomena of social import; the construction and utilization of developmentally and contextually sensitive assessment instruments; the design and evaluation of developmental interventions and enhancement programs; and the dissemination of developmental knowledge to individuals, families, communities, practitioners, and policy makers through developmental education, printed and electronic materials, the mass media, expert testimony, and community collaborations.

Given their belief in the importance for developmental analysis of systemically integrating all components within the ecology of human development, and their stress on integrating through collaboration and colearning the expertise of the researcher with the expertise of the community, proponents of ADS believe that researchers and the institutions within which they work are part of the developmental system that ADS tries to understand and enhance. ADS emphasizes that the scholar/university-community partnerships that they seek to enact are an essential means of contextualizing knowledge. By embedding scholarship about human development within the diverse ecological settings within which people develop, applied developmental scientists foster bidirectional relationships between research and practice. Within such relationships developmental research both guides and is guided by the outcomes of community-based interventions, for example, public policies or programs aimed at enhancing human development.

The growth of such outreach scholarship has fostered a scholarly challenge to prior conceptions of the nature of the world (Cairns, Bergman, & Kagan, 1998; R. M. Lerner & Miller, 1998;W. Overton, 1998;Valsiner, 1998).The idea that all knowledge is related to its context has promoted a change in the typical ontology within current scholarship. This change has emerged as a focus on relationism and an avoidance of split conceptions of reality, such as nature versus nurture (W. Overton, 1998). This ontological change has helped advance the view that all existence is contingent on the specifics of the physical and social-cultural conditions that exist at a particular moment of history (W. Overton, 1998; Pepper, 1942). Changes in epistemology that have been associated with this revision in ontology and contingent knowledge can be understood only if relationships are studied.

Accordingly, any instance of knowledge (e.g., the core knowledge of a given discipline) must be integrated with knowledge of (a) the context surrounding it and (b) the relation between knowledge and context. Thus, knowledge that is disembedded from the context is not basic knowledge. Rather, knowledge that is relational to its context, for example, to the community, as it exists in its ecologically valid setting (Trickett, Barone, & Buchanan, 1996), is basic knowledge. Having an ontology of knowledge as ecologically embedded and contingent rationalizes the interest of ADS scholars in learning to integrate what they know with what is known of and by the context (Fisher, 1997). It thus underscores the importance of colearning collaborations between scholars and community members as a key part of the knowledge-generation process (Higgins-D’Alessandro, Fisher, & Hamilton, 1998; R. M. Lerner & Simon, 1998a, 1998b). In sum, significant changes that have occurred in the way in which social and behavioral scientists (and human developmentalists more specifically) have begun to reconceptualize their roles and responsibilities to society is in no greater evidence than in the field of ADS (Fisher & Murray, 1996; R. M. Lerner, 2002a, 2002b; R. M. Lerner et al., 2000a, 2000b).

Human developmental science has long been associated with laboratory-based scholarship devoted to uncovering universal aspects of development by stripping away contextual influences (Cairns et al., 1998; Hagen, 1996; Youniss, 1990). However, the mission and methods of human development are being transformed into an ADS devoted to discovering diverse developmental patterns by examining the dynamic relations between individuals within the multiple, embedded contexts of the integrated developmental systems in which they live (Fisher & Brennan, 1992; Horowitz, 2000; Horowitz & O’Brien, 1989; Morrison, Lord, & Keating, 1984; Power, Higgins, & Kohlberg, 1989; Sigel, 1985). This theoretical revision of the target of developmental analysis from the elements of relations to interlevel relations has significant implications for applications of developmental science to policies and programs aimed at promoting positive human development.Arguably the most radical feature of the theoretical, research, and applied agenda of applied developmental scientists is the idea that research about basic relational processes of development and applications focused on enhancing person-context relations across ontogeny are one and the same. To explain this fusion, it is important to discuss in some detail the link between developmental systems theory and ADS.

From Developmental Systems Theories to Applied Developmental Science

Paul Mussen, the editor of the third edition of the Handbook of Child Psychology, presaged what today is abundantly clear about the contemporary stress on systems theories of human development. Mussen (1970, p. vii) said, “The major contemporary empirical and theoretical emphases in the field of developmental psychology . . . seem to be on explanations of the psychological changes that occur, the mechanisms and processes accounting for growth and development.” This vision alerted developmental scientists to a burgeoning interest not in structure, function, or content per se, but in change, in the processes through which change occurs, and in the means through which structures transform and functions evolve over the course of human life.

Today, Mussen’s (1970) vision has been crystallized. The cutting edge of contemporary developmental theory is represented by systems conceptions of process, of how structures function and how functions are structured over time. Thus, developmental systems theories of human development are not tied necessarily to a particular content domain, although particular empirical issues or substantive foci (e.g., motor development, successful aging, wisdom, extraordinary cognitive achievements, language acquisition, the self, psychological complexity, or concept formation) may lend themselves readily as exemplary sample cases of the processes depicted in a given theory (see R. M. Lerner, 1998a).

The power of developmental systems theories lies in their ability not to be limited or confounded by an inextricable association with a unidimensional portrayal of the developing person. In developmental systems theories the person is neither biologized, psychologized, nor sociologized. Rather, the individual is systemized. A person’s development is embedded within an integrated matrix of variables derived from multiple levels of organization. Development is conceptualized as deriving from the dynamic relations among the variables within this multitiered matrix.

Developmental systems theories use the polarities that engaged developmental theory in the past (e.g., nature/nurture, individual/society, biology culture; R. M. Lerner, 1976, 1986, 2002a), not to split depictions of developmental processes along conceptually implausible and empirically counterfactual lines (Gollin, 1981; W. Overton, 1998) or to force counterproductive choices between false opposites (e.g., heredity or environment, continuity or discontinuity, constancy or change; R. M. Lerner, 2002a), but to gain insight into the integrations that exist among the multiple levels of organization involved in human development. These theories are certainly more complex than their one-sided predecessors. They are also more nuanced, more flexible, more balanced, and less susceptible to extravagant or even absurd claims (e.g., that nature split from nurture can shape the course of human development; that there is a gene for altruism, militarism, or intelligence; or that when the social context is demonstrated to affect development the influence can be reduced to a genetic one; e.g., Hamburger, 1957; Lorenz, 1966; Plomin, 1986, 2000; Plomin, Corley, DeFries, & Faulker, 1990; Rowe, 1994; Rushton, 1987, 1988a, 1988b, 1997, 1999).

These mechanistic and atomistic views of the past have been replaced, then, by theoretical models that stress the dynamic synthesis of multiple levels of analysis, a perspective having its roots in systems theories of biological development (Cairns, 1998; Gottlieb, 1992; Kuo, 1930, 1967, 1976; T. C. Schneirla, 1956; T. C. Schneirla, 1957; von Bertalanffy, 1933). In other words, development, understood as a property of systemic change in the multiple and integrated levels of organization (ranging from biology to culture and history) comprising human life and its ecology, is an overarching conceptual frame associated with developmental systems models of human development.

Explanation and Application: A Synthesis

Thisstressonthedynamicrelationbetweentheindividualand his or her context results in the recognition that a synthesis of perspectives from multiple disciplines is needed to understand the multilevel integrations involved in human development. In addition, to understand the basic process of human development both descriptive and explanatory research must be conducted within the actual ecology of people’s lives.

Explanatory studies, by their very nature, constitute intervention research. The role of the developmental researcher conducting explanatory research is to understand the ways in which variations in person-context relations account for the character of human developmental trajectories, life paths that are enacted in the natural laboratory of the real world. To gain an understanding of how theoretically relevant variations in person-context relations may influence developmental trajectories, the researcher may introduce policies or programs as experimental manipulations of the proximal or distal natural ecology. Evaluations of the outcomes of such interventions become a means to bring data to bear on theoretical issues pertinent to person-context relations. More specifically, these interventions have helped applied developmental scientists to understand the plasticity in human development that may exist and that may be capitalized on to enhance human life (Csikszentmihalyi & Rathunde, 1998; R. M. Lerner, 1984).

The interindividual differences in intra-individual change that exist as a consequence of these naturally occurring interventions attest to the magnitude of the systematic changes in structure and function—the plasticity—that characterize human life. Explanatory research is necessary, however, to understand what variables, from what levels of organization, are involved in particular instances of plasticity that have been seen to exist. In addition, such research is necessary to determine what instances of plasticity may be created by science or society. In other words, explanatory research is needed to ascertain the extent of human plasticity or, in turn, to test the limits of plasticity (Baltes, Lindenberger, & Staudinger, 1998; R. M. Lerner, 1984).

From a developmental systems perspective, the conduct of such research may lead the scientist to alter the natural ecology of the person or group he or she is studying. Such research may involve either proximal or distal variations in the context of human development (R. M. Lerner & Ryff, 1978); in any case, these manipulations constitute theoretically guided alterations of the roles and events a person or group experiences at, or over, a portion of the life span.

These alterations are indeed, then, interventions: They are planned attempts to alter the system of person-context relations that constitute the basic process of change; they are conducted in order to ascertain the specific bases of, or to test the limits of, particular instances of human plasticity (Baltes, 1987; Baltes & Baltes, 1980). These interventions are a researcher’s attempt to substitute designed person-context relations for naturally occurring ones in an attempt to understand the process of changing person-context relations that provides the basis of human development. In short, basic research in human development is intervention research (R. M. Lerner et al., 1994).

Accordingly, the cutting edge of theory and research in human development lies in the application of the conceptual and methodological expertise of human developmental scientists to the natural ontogenetic laboratory of the real world. This placement into the actual ecology of human development of explanatory research about the basic, relational process of development involves the fusion of application with basic developmental science. To pursue the study of ontogeny from a developmental systems perspective, a research-application agenda that is focused on the relations between diverse individuals and their similarly diverse contexts is brought to the fore (R. M. Lerner, 2002a). In addition, however, scholars involved in such research must have at least two other concerns, ones deriving from the view that basic, explanatory research in human development is, in its essence, intervention research.

Research in human development that is concerned with one or even a few instances of individual and contextual diversity cannot be assumed to be useful for understanding the life course of all people. Similarly, policies and programs derived from such research, or associated with it in the context of a researcher’s tests of ideas pertinent to human plasticity, cannot hope to be applicable, or equally appropriate and useful, in all contexts or for all individuals. Accordingly, developmental and individual differences–oriented policy development and program (intervention) design and delivery must be a key part of the approach to applied developmental research for which we are calling.

The variation in settings within which people live means that studying development in a standard (e.g., a controlled) environment does not provide information pertinent to the actual (ecologically valid) developing relations between individually distinct people and their specific contexts (e.g., their particular families, schools, or communities). This point underscores the need to conduct research in real-world settings (Bronfenbrenner, 1974; Zigler, 1998) and highlights the ideas that (a) policies and programs constitute natural experiments (i.e., planned interventions for people and institutions) and (b) the evaluation of such activities becomes a central focus in the developmental systems research agenda we have described (R. M. Lerner, 1995; R. M. Lerner, Ostrom, & Freel, 1995).

In this view, then, policy and program endeavors do not constitute secondary work, or derivative applications, conducted after research evidence has been complied. Quite to the contrary, policy development and implementation, as well as program design and delivery, become integral components of the ADS approach to research; the evaluation component of such policy and intervention work provides critical feedback about the adequacy of the conceptual frame from which this research agenda should derive (Zigler, 1998; Zigler & Finn-Stevenson, 1992).

In essence, a developmental systems perspective leads us to recognize that if we are to have an adequate and sufficient science of human development, we must integratively study individual and contextual levels of organization in a relational and temporal manner (Bronfenbrenner, 1974; Zigler, 1998). And if we are to serveAmerica’s citizens and families through our science, and if we are to help develop successful policies and programs through our scholarly efforts—efforts that result in the promotion of positive human development—then we may make great use of the integrative, temporal, and relational model of the person and of his or her context that is embodied in the developmental systems perspective forwarded in developmental system theories of human development.

Toward the Testing of a Developmental Systems Approach to Applied Developmental Science

The key test of the usefulness of the integrative, relational ideas of applied developmental scientists lies in a demonstration of the greater advantages for understanding and applying a synthetic focus on person-context relations—as compared to an approach to developmental analysis predicated on splitting individual from context or on splitting any level within the developmental system from another (e.g., through genetic reductionism, splitting biological from individualpsychological or social levels; e.g., as in Rowe, 1994, or Rushton, 1999, 2000). In other words, can we improve understanding of human development, and can we enhance our ability to promote positive outcomes of changes across life by adopting the relational approach of an ADS predicated on developmental systems thinking?

We believe the answer to this question is yes, and to support our position we consider scholarship that illustrates how a focus on the person-context relation may enhance understanding of the character of human development and, as well, of the ways in which applications linking person and context in positive ways can enhance human development across the life span. The scholarship we review considers the importance of understanding the match, congruence, quality of fit, or integration between attributes of individuals and characteristics of their contexts for understanding and promoting healthy, positive human development.

Although there are numerous ways in which the literature pertinent to person-context relations may be partitioned in order to ascertain the nature of the support that exists for the developmental systems approach to ADS, we have elected to concentrate on models of person-context relations focused primarily on families, schools, and communities. We believe the literatures associated with these instances of the context afford an assessment of three settings integral to the lives of people across much of the life span. As well, these three foci provide a means to consider integrated issues of research, policies, and programs pertinent to the promotion of positive development across much of ontogeny.

Models of Person-Context Relation

Biological (organismic) characteristics of the individual affect the context; for example, adolescents who look different as a consequence of contrasting rates of biological growth associated for instance with earlier versus later maturation elicit different social behaviors from peers and adults (Brooks-Gunn, 1987; R. M. Lerner, 1987a, 1987b; Petersen, 1988). At the same time, contextual variables in the organism’s world affect its biological characteristics (e.g., girls growing up in nations or at times in history with better health care and nutritional resources reach puberty earlier than do girls developing in less advantaged contexts; Katchadourian, 1977; Tanner, 1991).

Accordingly, scholars using developmental systems thinking to frame their work seek to identify how variables from the levels involved in person-context relations fit together dynamically (i.e., in a reciprocally interactive way) to provide bases for behavior and development. For instance, the goodness-of-fit model (Chess & Thomas, 1984; Thomas & Chess, 1977) and the stage-environment fit model (Eccles, 1991; Eccles & Midgley, 1989), both of which are discussed in greater detail later, represent two important ways in which scholars interested in developmental systems have explored the import of dynamic person-context relations for positive development.

Capitalizing on the tradition of person-context scholarship embodied in such models, other scholars, interested in applying developmental science to promote positive youth development by improving person-context relations, have attempted to understand and enhance the integration of individual and ecological characteristics in the service of fostering healthier developmental trajectories. This scholarship expands the focus of person-context relations beyond child-parent, person-family, or student-teacher (classroom, school) foci to include community-level variables; as such, it includes an explicit recognition of the ethos and values of a community for marshalling its strengths or assets around a vision of improved, healthy trajectories of person-context relations for young people.

The idea involved in all of these variants of personcontext relational conceptions is the same. Just as a person brings his or her characteristics of individuality to a particular social setting, there are characteristics of the context (e.g., social demands placed on the person) that exist by virtue of the social and physical components of the setting. These ecological characteristics may take the form of (a) attitudes, values, or stereotypes that are held by others in the context regarding the person’s attributes (either physical or behavioral characteristics); (b) the attributes (usually behavioral) of others in the context with whom the individual must coordinate, or fit, his or her attributes (also, in this case, usually behavioral) for adaptive interactions to exist; (c) the physical characteristics of a setting (e.g., the presence or absence of access ramps for those with motor handicaps) that require the person to possess certain attributes (again, usually behavioral abilities) for the most efficient interaction within the setting to occur; or (d) the social assets, resources, or strengths of a neighborhood or community (e.g., mentoring programs for students, community policing programs, or educationally enriching after-school programs for young children).

A congruence, match, or goodness of fit between a person’s attributes of individuality (e.g., her/his temperamental characteristics, developmental level) and the features of his or her social and physical ecology (e.g., the demands placed on her/him for particular behaviors by parents, classroom teachers, school peer groups, or other significant people in her/his life) may be established because the individual has characteristics that act on the environment and, at the same time, because the environment acts on her or his characteristics (Chess & Thomas, 1984, 1999; J. V. Lerner & Lerner, 1983; R. M. Lerner & Lerner, 1989; Thomas & Chess, 1977). These two components of the developmental system— individual attributes and ecological characteristics (such as demands and resources)—may interact to promote either adaptive or unhealthy outcomes.

Of course, any instance of match, congruence, positive integration, or fit may result in either positive or negative outcomes, depending on the characteristics extant across the other levels of the developmental system at a given point in time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Elder, 1998). However, given that the individual is at the center of these reciprocal actions (or dynamic interactions), individuals, through their own actions, are a source of their own development (R. M. Lerner & Busch-Rossnagel, 1981; R. M. Lerner & Walls, 1999). In short, within developmental systems theories there is a third source of development—the individual (see, e.g., Schneirla, 1957).

The basis of the specifications provided by these models of person-context relations for positive development lies in this third source of development. Given the influences of the individual (e.g., the child) on his or her context, and thus as a producer of her or his own development, one implication of developmental systems thinking for the understanding of human development is through the creation of person effects.

To illustrate, consider the person during his or her childhood (and thus consider child effects on the developmental process; R. M. Lerner & Busch-Rossnagel, 1981; R. M. Lerner & Walls, 1999). How we behave and think as adults— and especially as parents—is very much influenced by our experiences with our children. Our children rear us as much as we do them (R. M. Lerner, Rothbaum, Boulos, &

Castellino, in press). The very fact that we are parents makes us different adults than we would be if we were childless. But, more importantly, the specific and often special characteristics of a particular child influence us in very unique ways. How we behave toward our children depends quite a lot on how they have influenced us to behave. Such child influences are the basis of child effects.

Child effects emerge largely as a consequence of a child’s individual distinctiveness. All children, with the exception of genetically identical (monozygotic) twins, have a unique genotype, that is, a unique genetic inheritance. Similarly, no two children, including monozygotic twins, experience precisely the same environment. As such, because of personcontext fusions, all individuals have systematic characteristics of individuality, distinct features that arise from a probabilistic epigenetic interrelation of genes and environment (Gottlieb, 1970, 1983, 1991, 1992, 1997).

Child effects elicit a “circular function” (Schneirla, 1957) in individual development: Children stimulate differential reactions in their parents, and these reactions provide the basis of feedback to the child; that is, return stimulation influences children’s further individual development. The bidirectional child-parent relationships involved in these circular functions underscore the point that children (and adolescents and adults) are producers of their own development and that individuals’ relations to their contexts involve bidirectional exchanges (R. M. Lerner, 1982). The parent shapes the child, but part of what determines the way in which parents do this is children themselves.

In short, children shape their parents—as adults, as spouses, and of course as parents per se—and in so doing children help organize feedback to themselves, feedback that contributes further to their individuality and thus starts the circular function all over again (i.e., returns the child effects process to its first component). Characteristics of behavioral or personality individuality allow the child to contribute to this circular function. However, this idea of circular functions needs to be extended; that is, in and of itself the notion is mute regarding the specific characteristics of the feedback (e.g., its positive or negative valence) that children will receive as a consequence of their individuality. In other words, to account for the specific character of child-family relations, the circular functions model needs to be supplemented. The first model of person-context relations we shall consider—the goodness-offit model—makes this contribution to the understanding of circular functions within the family.

The Goodness-of-Fit Model of Person-Context Relations in Families

The goodness-of-fit model specifies that a person’s characteristics differentially meet the demands of his or her setting, providing a basis for the specific feedback attained from the socializing environment. Although the goodness-of-fit model is put forward as a general model to assist in understanding the valence of the feedback associated with circular functions within and across all instances of person-context relations (Chess & Thomas, 1999; Thomas & Chess, 1970, 1977, 1981), much of the literature involving tests of this model have been linked either to understanding family relations or to the differences between interactions in the family and other key contexts of child development (e.g., the school).

For example, teachers and parents may have relatively individual and distinct expectations about behaviors desired of their students and children; these different expectations typically derive from contrasting attitudes, values, or stereotypes associated with the school versus the home. For instance, teachers may prefer students who show little distractibility, whereas parents might prefer their children to be moderately distractible, for example, when they require their children to move from watching television to the dinner table and then on to bed. Children whose behavioral individuality is either generally distractible or generally not distractible would differentially meet the demands of these two contexts. Problems of adjustment to school or to home might thus develop as a consequence of a child’s lack of match (or goodness of fit) in either or both settings. By this analysis, distractible children should, therefore, never be blamed for a poor fit. It is, rather, the dynamic relationship between the child and his or her context(s) that determines the adaptability of the fit (i.e., the functional significance of the fit, e.g., for positive social relations in the context).

When looking specifically at the child’s contribution to fit, one may specify different competencies that a child might possess to attain a good fit within and across time within given contexts. These competencies include appropriately evaluating (a) the demands of a particular context, (b) the individual’s psychological and behavioral characteristics, and (c) the degree of match that exists between the two. In addition, other cognitive and behavioral skills are necessary. The child must have the ability to select and gain access to those contexts with which there is a high probability of match and to avoid those contexts where poor fit is likely. In contexts that are assigned rather than selected—for example, family of origin or assigned elementary school class—the child must have the knowledge and skills necessary either to change him- or herself to fit the demands of the setting or to alter the context to better fit his or her attributes (Mischel, 1977; Snyder, 1981). In most contexts multiple types of demands will impinge on the person, each with distinct pressures on the individual. The child needs to be able to detect and evaluate such complexity and judge which demand it is best to adapt to when all cannot be met. In these instances, as the child develops competency in self-regulation (Brandtstädter, 1998, 1999; Eccles, Early, Frasier, Belansky, & McCarthy, 1997; Heckhausen, 1999), the child will be able to become an active selector and shaper of the contexts within which he or she develops. Thus, as the child’s agency (Bakan, 1966) develops, it will become increasingly true that he or she rears his or her parents as much as they do him or her.

Alexander Thomas and Stella Chess (1977, 1980, 1981; Chess & Thomas, 1984, 1999) asserted that if a child’s characteristics of individuality provide a good fit (or match) with the demands of a particular setting, adaptive outcomes will accrue in that setting. Those children whose characteristics match most of the settings within which they exist should receive supportive or positive feedback from the contexts and should show evidence of the most adaptive behavioral development. In turn, of course, poorly fit or mismatched children should show alternative developmental outcomes. The characteristics of individuality through which children may differentially fit their contexts involve what children do, why children show a given behavior, and how children do whatever they do.

Temperament and Tests of the Goodness-of-Fit Model

Much of the initial evidence supporting the use of the goodness-of-fit model is derived from the Thomas and Chess (1977; Chess &Thomas, 1996, 1999) NewYork Longitudinal Study (NYLS). For instance, information relevant to the goodness-of-fit model exists as a consequence of the multiple samples present in the project. The core NYLS sample was composed of 133 middle-class, mostly European American children of professional parents who were followed from infancy through young adulthood. In addition, a sample of 98 Puerto Rican children of working-class parents was followed for about seven years. The children from both samples were studied from at least the first month of life onward. Although the distribution of temperamental attributes was not different in the two samples, the import of the attributes for psychosocial adjustment was quite disparate.

Two examples that relate to the concept of “easy” versus “difficult” temperament (Chess & Thomas, 1984, 1999; Thomas & Chess, 1977) may suffice to illustrate this distinction. Chess and Thomas (1984, 1999) explained that the fit between the child’s temperament and the caregiver’s demands may be associated with distinct types of parental or family relations. For instance, temperamentally difficult children may be moody or biologically arrhythmic and, as a result, may not fit with the preferences, expectations, or schedules of caregivers. By contrast, children with easy temperaments may be rhythmic children and have a positive mood and, as a result, have a better fit with the preferences, expectations, or schedules of the caregivers. However, a child’s temperamental ease or difficulty does not reside in the child but in the dynamic relations involving the child, the parent, and the larger ecology of human development. What may be difficult in one setting, or a predictor of negative developmental outcomes, may be irrelevant or, instead, a predictor of positive outcomes under different conditions of the developmental system.

To illustrate the significance of individual temperament on the goodness of fit between person and context, the impact of low regularity or rhythmicity of behavior, particularly in regard to sleep-wake cycles, may be considered. Of the two samples of families in the NYLS, the Puerto Rican parents studied by Thomas and Chess (1977; Thomas, Chess, Sillen, & Mendez, 1974) placed no demands in regard to rhythmicity of sleep on the infant or child during at least the first five years of live. In fact, Puerto Rican parents allowed their child during the first five years of life to go to sleep and wake up at any time. These parents molded their schedule around their children. Because this sample of parents was so accommodating, there were no problems of fit associated with an arrhythmic infant or child. In addition, neither within the infancy period nor throughout the first five years of life did arrhythmicity predict adjustment problems in the Puerto Rican children. In this sample arrhythmicity remained continuous and independent of adaptive implications for the child. In turn, in the predominantly European American, middle-class families, strong demands for rhythmic sleep patterns were maintained. Most of the mothers and fathers in this sample worked outside the home (Korn, 1978), and sleep arrhythmicity in the child interfered with parents’getting sufficient rest at night to perform optimally at work the next day. Thus, an arrhythmic child did not fit with parental demands, and consistent with the goodness of fit model, arrhythmicity was a major predictor of problem behaviors both within the infancy years and through the first five years of life (Korn, 1978; Thomas et al., 1974).

There are at least two ways of viewing this finding. First, consistent with the idea that children influence their parents, it is significant to note that sleep arrhythmicity in the European American sample resulted in parental reports of fatigue, stress, anxiety, and anger (Chess & Thomas, 1984, 1996, 1999; Thomas et al., 1974). It is possible that the presence of arrhythmicity altered previous parenting styles in this NYLS sample in a way that constituted negative feedback (negative parenting) directed to the child—feedback that was then associated with the development of problem behaviors in the child.

A second interpretation of this finding arises from the fact that problem behaviors in the children were identified initially on the basis of parental report. Regardless of problem behaviors evoked in the parent by the child or of any altered parent-child interactions that thereby ensued, one effect of the child on the parent was to increase the probability of the parent labeling the child’s temperamental style as problematic and so reporting it to the NYLS staff psychiatrist. The current analyses of the NYLS data do not allow for a discrimination between these two possibilities.

The data in the NYLS do indicate that the European American sample took steps to change their arrhythmic children’s sleep patterns. Because temperament may be modified by person-context interactions, low rhythmicity tended to be discontinuous for most of these children. That these parents modified their children’s arrhythmicity is an instance of a child effect on its psychosocial context. That is, the child produced alterations in parental caregiving behaviors regarding sleep. That these child effects on the parental context fed back to the child and influenced her or his further development is consistent with the finding that sleep arrhythmicity was discontinuous among these children.

Thus, in the predominantly European American, middleclass sample, early infant arrhythmicity tended to be a problem during this time of life but proved to be neither continuous nor predictive of later adjustment problems. In turn, in the Puerto Rican sample, arrhythmicity, though continuous, was not a poor fit with the context of the child during infancy or within the first five years of life. This is not to say that the parents in the Puerto Rican families were not affected by their children’s sleep arrhythmicity. As with the European American parents, it may be that the Puerto Rican parents had problems of fatigue or suffered family or work-related problems due to irregular sleep patterns produced in them as a consequence of their child’s sleep arrhythmicity. Again, the data analyses in the NYLS do not indicate this possible child effect on the Puerto Rican parents.

The data do underscore the importance of considering the fit between the individual and the demands of the psychosocial context of development, in that it indicates that arrhythmicity did begin to predict adjustment problems for the Puerto Rican children when they entered the school system. Their lack of a regular sleep pattern interfered with their getting sufficient sleep to perform well in school and often caused them to be late to school (Korn, 1978; Thomas et al., 1974). Thus, although before the age of 5 years only one Puerto Rican child presented a clinical problem diagnosed as a sleep disorder, between ages 5 and 9 years almost 50% of the Puerto Rican children who developed clinically identifiable problems were diagnosed as having sleep problems.

Another example of how the different demands of the two family contexts studied in the NYLS provide different presses for adaptation relates to differences in the demands of the families’ physical contexts. As noted by Thomas et al. (1974), as well as Korn (1978), there was a very low overall incidence of behavior problems in the Puerto Rican sample of children in their first five years of life, especially when compared to the corresponding incidence among the European American sample of children. If a problem did arise during this time among the Puerto Rican sample, it was most likely to be a problem of motor activity. Across the first 9 years of their lives, of those Puerto Rican children who developed clinical problems, 53% presented symptoms diagnosed as involving problematic motor activity. The parents of these children complained of excessive and uncontrollable motor activity. However, in the European American sample, only one child (a child with brain damage) was characterized in this way.

The Puerto Rican parents’ reports of “excessive and uncontrollable” activity in their children do constitute an example of a child effect on the parents. That is, a major value of the Puerto Rican parents in the NYLS was child obedience to authority (Korn, 1978). The type of motor activity shown by the highly active children of these Puerto Rican parents was inconsistent with parental perceptions of an obedient child (Korn, 1978).

Moreover, the Puerto Rican children’s activity-level characteristics serve as an illustration of the embeddedness of the child temperament home-context relation in the broader community context. The Puerto Rican families usually had several children and lived in small apartments, where even average motor activity tended to impinge on others in the setting. At the same time, Puerto Rican parents were reluctant to let their children out of the apartment because of the actual dangers of playing on the streets of their (East Harlem) neighborhood—perhaps especially for children with high activity levels.

In the predominantly European American, middle-class sample, the parents had the financial resources to provide large apartments or houses for their families. There were typically suitable play areas for the children both inside and outside the home. As a consequence, the presence of high activity levels in the home of the European American sample did not cause the problems for interaction that they did in the Puerto Rican group. Thus, as Thomas, Chess, and Birch (1968; Thomas et al., 1974) emphasized, the mismatch between temperamental attribute and physical environmental demand accounted for the group difference in the import of high activity level for the development of reported behavioral problems in the children.

Chess and Thomas (1999) reviewed other data from the NYLS, and from independent data sets, that tested their temperament-context, goodness-of-fit model. One very important study they discussed was conducted by de Vries (1984), who assessed the Masai tribe living in the sub-Sahara region of Kenya at a time when a severe drought was beginning. After obtaining temperament ratings on 47 infants, aged 2 to 4 months, de Vries identified from within his sample the 10 infants with the easiest temperaments and the 10 with the most difficult temperaments. Five months later, at a time when 97% of the cattle herd had died from the drought, he returned to the tribal area. Given that the basic food supply was milk and meat, both derived from the tribe’s cattle, the level of starvation and death experienced by the tribe was enormous. De Vries located the families of seven of the easy babies and six of the difficult ones. The families of the other infants had moved to try to escape the drought. Of the seven easy babies, five had died. All of the difficult babies had survived.

Chess and Thomas (1999) suggested two reasons for this dramatic finding. First, difficult infants cried louder and more frequently than did the easy babies. Parents fed the difficult babies either to stop their excessive crying or because they interpreted the cries as signals of extreme hunger. Alternatively, there may be a cultural reason for the survival of the difficult infants, one that would not have emerged to affect behavior during a time of plentiful food, when both easy and difficult babies could have been soothed easily when crying due to hunger. Chess and Thomas suggested that the parents, under the nonnormative historical conditions of the drought, saw the difficult babies not as a problem to be managed but as an asset to the survival of the tribe. As a consequence, the parents might have actually chosen “for survival these lusty expressive babies who have more desirable characteristics according to the tribe’s cultural standards” (Chess & Thomas, 1999, p. 111).

In the de Vries (1984) study, the parent-child relation, embedded in the developmental system at a time of nonnormative natural environment disaster, led to a switch in the valence, or meaning, of “difficulty” and resulted in a dramatic difference in adaptive developmental outcome (survival or death). Among the core NYLS sample, living under “privileged” conditions in New York City, difficult babies comprised 23% of the clinical behavior problem group (10 babies) but only 4% (4 cases) of the nonclinical sample (Thomas et al., 1968, p. 78). From these collective findings, Chess and Thomas (1999) stressed that the relationship between child and parent—a relation interactive with the multiple levels of the developmental system, including the physical ecology, culture, and history—must be the frame of reference for understanding the role of temperament in parent-child relationships and in the enactment and outcomes of parenting.

A similar conclusion may be derived from the research of Super and Harkness (1981). Studying the Kipsigis tribe in either the rural village of Kokwet, Kenya, or in the urban setting of Nairobi, Kenya, Super and Harkness found that sleep arrhythmicity had different implications for mother-infant interactions. Rural Kipsigis is an agricultural community, and the tribe assigns primary (and in fact virtually exclusive) caregiving duties to the mother, who keeps the infant in close proximity to her (either on her shoulder or within a few feet of her), even if she is working in the fields (or is socializing, sleeping, or the like). Sleep arrhythmicity in such a context is not a dimension of difficulty for the mother because whenever the infant awakes, she or he can be fed or soothed by the mother with little disruption of her other activities. By contrast, however, Kipsigis living in Nairobi are not farmers but office workers, professionals, and the like. In this context, they cannot keep the infant close to them at all times and, as a consequence, Super and Harkness found that sleep arrhythmicity is a sign of difficulty and is associated with problems for the mother and for her interactions with the infant.

Still other studies support the idea that the goodness of fit between parent and child influences the quality of interrelations between these individuals and is associated with the nature of the developmental outcomes for youth. Galambos and Turner (1999) examined adolescent and parent temperaments as predictors of the quality of parent-adolescent relationships. They reported that both parent and adolescent temperament explain unique portions of the variance in parent-adolescent relationships. Adaptable adolescents are more likely to have accepting mothers who tend not to rely on the induction of guilt as a means of control as well as more accepting fathers than other, less adaptable adolescents. Mothers’ level of adaptability was also found to contribute uniquely and additively to the parent-adolescent relationship, in that mothers who were more highly adaptable were more accepting of their adolescents. The level of acceptance by mothers was highest when both mother and adolescent adaptability were high.

Moreover, Galambos and Turner (1999) found that adolescent and parent temperaments interact to affect the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship. For instance, conflict between mothers and sons was highest in relationships where the mothers were less adaptable and sons were less active. Conflict between mothers and daughters was highest in relationships where the mother was less adaptable and the daughter was more active. Similarly, as level of activity in female adolescents increased, more conflicts with parents were reported. This result was not found with male adolescents. In turn, when both fathers and female adolescents were low in adaptability, fathers used more psychological control and female adolescents reported more conflicts with parents.

Similarly, using parental stress as a measure of goodness of fit between parent and adolescent characteristics, Bogenschneider, Small, and Tsay (1997) found that, within a study of 8th- to 12th-graders and their parents, a mismatch between a parent and adolescent led to levels of stress that interfered with competent parenting. Schraeder, Heverly, and O’Brien (1996) reported comparable findings. Assessing the later-life effects of low birth weight on child adjustment in the home and in the school, Schraeder et al. noted that features of the social environment, as well as the fit between the child and the social environment, played a greater role in shaping the behavior of the child than did an initial biological risk of very low birth weight. Underscoring the idea that fit involves multiple instances or levels of the context of human development, Flanagan and Eccles (1993) reported that developmental difficulties associated with school may be amplified by parental work status. A decline in parental work status coupled with students’ transition to junior high school were associated with an increase in school adjustment problems, as indicated by teachers’ assessments of disruptive behavior (Flanagan & Eccles, 1993).

Thus, data pertinent to the goodness-of-fit model underscore the idea that fit involves several levels of the developmental system, that is, the developing individual and multiple contexts—family, school, and culture in the literature just reviewed.

The Stage-Environment Fit Model of Adolescent-School Relations

Through a focus on young adolescents and their transition from elementary school to either junior high or middle school, JacquelynneEcclesandhercolleagues(e.g.,Eccles&Harold, 1996; Eccles et al., 1996; Fuligni, Eccles, & Barber, 1995; Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989a, 1989b) have offered a theoretically nuanced and empirically highly productive approach to understanding the significance of person-context relations for healthy development. Eccles and her colleagues argue that there is a connection between a child’s developmental level and the developmental appropriateness of the characteristics of the child’s social context. Eccles, Midgley, et al. (1993) labeled this type of person-context fit stageenvironment fit. This model has been used to explore the nature of developmental outcomes that children obtain in their environments, such as school.As Eccles (1997) points out,

Exposure to the developmentally appropriate environment facilitate[s] both motivation and continued growth; in contrast, exposure to developmentally inappropriate environments, especially developmentally regressive environments, creates a particularly poor person-environment fit, which lead[s] to declines in motivation as well as detachment from the goals of the institution. (p. 531)

Using the stage-environment fit model to study adolescentschool relations, Eccles and her colleagues have noted that changes that young adolescents experience during their transition from elementary school to junior high school (e.g., changes in self-esteem, motivation, and academic achievement) have the potential to negatively affect the adolescents’ positive development when junior high schools do not provide developmentally adequate contexts (Eccles, Lord, & Midgley, 1991; Eccles & Midgley, 1989; Eccles & Roeser, 1999; Wigfield, Eccles, Mac Iver, Reumann, & Midgley, 1991). Contrary to students’ developmental needs, the school environments that young adolescents encounter on their transfer from elementary to junior high school tend to emphasize

competition, social comparison, and ability self-assessment at a time of heightened self-focus; decrease[d] decision making and choices at a time when the desire for control is growing up; . . . lower level cognitive strategies at a time when the ability to use higher level strategies is increasing; and . . . [disruption of] social networks at a time when adolescents are especially concerned with peer relationships. (Eccles & Roeser, 1999, p. 533)

There may be several instances of this mismatch between young adolescents’ developmental needs at their specific developmental stage and the demands of their school context. For instance, characteristics of middle schools or junior high schools, such as size and departmentalization, may negatively effect early adolescents’ development, particularly by lowering self-esteem (Simmons & Blyth, 1987; Simmons, CarltonFord, & Blyth, 1987). Even though junior high schools afford an opportunity to meet many new peers, they are much larger in size than elementary schools and may therefore foster alienation, isolation, and difficulties with intimacy (Simmons et al., 1987). Similarly, Eccles and Midgley (1989) noted that classrooms in junior high schools are characterized by greater teacher control and emphasis on discipline; less positive student-teacher relationships; and decreased opportunities for students to make their own decisions, choose among different options, and exercise self-management skills. Junior high school teachers foster class practices that encourage the use of social comparison, ability self-assessment, and higher standards for judging students’performance than do teachers in elementary schools (Eccles & Midgley, 1989). Moreover, teachers in junior high schools, compared to teachers in elementary schools, have been found to be stronger proponents of students’ needing discipline and control, to consider their students to be less trustworthy, and to feel less effective in their work with young adolescent students (Eccles et al., 1991). In addition, young adolescents who had high-efficacy teachers in elementary school but then moved to a lowefficacy teacher in junior high school had lower expectations and perceptions of their own academic performance in their first year of junior high than did students who came from lowefficacy teachers or, once in junior high, were paired with a high-efficacy teacher (Eccles et al., 1991). Wigfield et al. (1991) found that less positive student-teacher relationships and (mathematics) teachers’ feeling less efficacious could be partly responsible for early adolescents’decline in confidence in social skills on their transition to junior high school.

In turn, Roeser, Eccles, and Sameroff (1998, 2000) found that academic motivation, achievement, and emotional wellbeing are promoted when the school environment supports the development of competence, autonomy, and positive relationships with teachers. To the extent that the school environment inhibits the development of feelings of competence, autonomy, and positive relationships, students will feel alienated academically, emotionally, and behaviorally. As such, Roeser et al. (1998, 2000) encouraged educators and school counselors to examine school environments through a “developmental lens” (Roeser et al., 1998, p. 345). Adolescents who report positive academic motivation and emotional well-being perceive their schools as “more developmentally appropriate in terms of norms, practices, and teacher-student interactions, whereas those manifesting poorer functioning reported less developmentally appropriate school environments” (Roeser et al., 1998, p. 345).

To support the development of a sense of competence in early adolescence, through building a better fit between the developing adolescent and the school context, Roeser et al. recommended that middle schools focus on and promote positive teacher regard for students and implement instructional practices that enable students to view self-improvement, effort, and mastery of tasks as the “hallmarks of competence andacademicsuccess”(Roeseretal.,1998,p.346)ratherthan competition, ability relative to peers, and the rewarding of high achievers. Roeser et al. cautioned that focusing on ability rather than effort during the stage of early adolescence is an inappropriate goal for schools, as all young adolescents are self-conscious and susceptible to social comparisons.Afocus on school ability is a particularly detrimental goal for adolescents having academic and/or emotional difficulties.

Similarly, to support the need for autonomy in middle school, and thereby enhancing the development of positive academic and emotional functioning in early adolescence, Roeser et al. (1998, 2000) suggested that middle schools provide students with opportunities to make choices (e.g., in relation to class seating, topics of discussion, and curricula development). In addition, middle schools should create and nurture opportunities for teachers to design curricula that fit the needs and interests of their students so that students can become more involved and invested in their own learning (Roeser et al., 1998, 2000). Moreover, because adolescents who perceive their teachers as providers of both emotional and academic support are less likely to feel alienated from the school environment or to experience emotional distress, Roeser et al. suggested that middle schools provide smaller communities of learning.

The changes in the school context that Roeser et al. (1998, 2000) indicated are needed to promote or better fit with the developmental characteristics of adolescents may be especially important for youth who have expressed academic difficulties prior to a transition to a new school setting. These adolescents are particularly vulnerable to developing the negative developmental outcomes as a consequence of poorness of fit (Eccles et al., 1991; Eccles et al., 1996).

In short, negative developmental outcomes may derive from a poorness of fit between a student’s orientation to learning and the curriculum; between the student and the teaching style or the instructional focus at the junior high or middle school; or between the availability in the classroom of sufficient decision-making opportunities for students and their needs to feel effective in class and to have more autonomy and opportunities in their learning environment (Eccles, 1997; Eccles et al., 1996). Moreover, adolescents’ perceptions of stage-environment fit can predict also motivation, achievement, and emotional functioning (Roeser et al., 1998).

For young adolescents making a transition into middle or junior high school, changes in classroom environment and teacher-student relations can impact the stage-environment fit (i.e., the balance between students’ developmental stage and characteristics of their context). A poor fit may have a negative impact on student motivation and performance (Eccles et al., 1991).

Eccles (1997) concluded that if we want to ensure that adolescents’ experiences of the transition are positive and that the match between the adolescents’developmental needs and the school context is a good one, developmentally appropriate educational environments for young adolescents need to be provided. An instance of a developmentally appropriate environment for early adolescent girls, for example, would be classrooms sensitive to gender-bound learning styles, that is, classrooms in which instructions are taught in more cooperative and person-centered ways (Eccles, 1997), to which girls may find it easier to relate. Classrooms such as these are likely to be more motivating as well as better equipped to support students’ developmental needs, therefore contributing to students’ healthy developmental outcomes.

In sum, by introducing to school environments changes that will ensure better fit between children’s developmental needs and characteristics of the school environment, one can create a balanced stage-environment fit, one that will contribute to the promotion of positive youth development. As such, the utility of the student-school relational ideas that Eccles and her colleagues have introduced could possibly be extended to further our understanding of other instances of person-context relations. In addition, the idea of fit may apply to other levels within the developmental system; if so, the relational ideas of Eccles and colleagues and of Thomas and Chess can provide guidance for program innovations or policy engagement aimed at influencing changes in the developmental system in a manner that would continue to promote positive development in young people.

That is, the work of Thomas and Chess (e.g., 1977; Chess & Thomas, 1999) and Eccles (e.g., 1991; Eccles, Lord et al., 1997) supports the idea that by enhancing the fit between individuals and their contexts, positive development may be promoted. It may be possible, then, through the ideas embodied in this work, to extend the utility of person-context relations into more macro instances of individual-context relations. One may ask if it is possible whether, through program innovations at the level of communities, one can simultaneously understand the efficacy of relational analyses of human development and influence changes in the developmental system that promote the positive development of people. One way to address this issue is to explore work on the links between individuals and community settings, which have been studied by applied developmental scientists trying to promote positive youth development among adolescents.

The Integration of Individual and Community Assets in the Promotion of Positive Youth Development

What is required at levels beyond the family or school—for instance, at the level of an entire community—to promote healthy, positive development among young people? Building on developmental systems ideas pertinent to positive person-context relations as integral to healthy development, Damon (1997) envisioned the creation of a youth charter in each community in the United States and in the world. The charter consists of a set of rules, guidelines, and plans of action that each community can adopt to provide its youth with a framework for development in a healthy manner, that is, to build positive relations with other individuals and institutions in their community.

The youth charter reflects “a consensus of clear expectations shared among the important people in a young person’s life and communicated to the young person in multiple ways” (Damon & Gregory, in press, p. 10). Damon and Gregory explained that their approach constitutes a shift along four dimensions in the study of youth:

a positive vision of youth strengths, a use of community as the locus of developmental action, an emphasis on expectations for service and social responsibility, and a recognition of the role of moral values and religious or spiritual faith. (p. 7)

Consistent with the relational emphasis in developmental systems theory, Damon and Gregory (in press) emphasize that

in a whole community, it is possible to find many people who can introduce young people into the positive, inspirational possibilities of moral commitment. Similarly, an entire community affords many opportunities for authentic service activities, such as helping those in need, that can provide young people with a chance to experience the psychological rewards of moral commitment. . . . In places that operate like true communities, there are many ways in which families, schools, workplaces, agencies, and peer groups connect with one another through their contact with youth. For example, schools are influenced by the values and attitudes that students pick up in their families. Students’ family lives are in turn influenced by their quest for academic achievement, which fills their after school time with homework—and which in turn is supported on the home front. A young person’s identity formation, rooted initially in the family, is shaped by a sense of belonging in the community, including sports teams, media, clubs, religious institutions, and jobs. In such communities, there also is concordance between the norms of the peer culture and those of adults. . . . A well-integrated and consciously developed pattern of relationships can provide a stabilizing transformational structure that produces equally integrated identities as workers and citizens and parents; no single institution has the resources to develop all of these roles alone (Ianni, 1989, p. 279). Ianni’s name for this stabilizing structure is a “youth charter.” (pp. 10–12)

Damon (1997) described how youth and significant adults in their community (e.g., parents, teachers, clergy, coaches, police, and government and business leaders) can create youth partnerships to pursue a common ideal of positive moral development and intellectual achievement:

To build a youth charter, community members go through a process of discussion, a movement towards agreement, and the development and implementation of action plans. Elements of the process include special town meetings sponsored by local institutions; constructive media coverage on a periodic basis; and the formation of standing committees that open new lines of communication among parents, teachers, and neighbors. (Damon & Gregory, in press, p. 13)

For example, Damon (1997) explained how a youth charter can be developed to maximize the positive person-context experiences and long-term desired developmental outcomes of youth in community sports activities. For instance, he noted that participation in sports is a significant part of the lives of many contemporary adolescents, and he pointed out that there may be important benefits of such participation. Young people enhance their physical fitness, learn athletic and physical skills, and, through sports, experience lessons pertinent to the development of their character (e.g., they learn about the importance of diligence, motivation, teamwork, balancing cooperation versus competition, balancing winning and losing, and the importance of fair play; Damon, 1997). Moreover, sports can be a context for positive parentchild relations, and such interactions can further the adolescent’s successful involvement in sports. For example, parental support of their male and female adolescents’participation in tennis is associated with the enjoyment of the sport by the youth and with an objective measure of their performance (Hoyle & Leff, 1997).

However, Damon (1997) noted as well that organized and even informal opportunities for sports participation for youth, ranging from Little League, soccer, or pickup games in school yards, often fall short of providing these relational benefits for young people. He pointed out that in modern American society sports participation is often imbued with a “win at any cost” orientation among coaches and, in turn, their young players.In addition, parents may also have this attitude.Together, a value is conveyed that winning is not just the main goal of competition, but the only thing (Damon, 1997, p. 210).

Damon believes that this orientation to youth sports corrupts the purposes of youth participation in sports. Parents and coaches often forget that most of the young people on these teams will not make sports a life career and, even if they do, they—as well as the majority of young people involved in sports—need moral modeling and guidance about sportsmanship and the significance of representing, through sports, not only physically but also psychologically and socially healthy behaviors (Damon, 1997).

In order to enable youth sports to make these contributions to positive adolescent development, Damon (1997) proposed a youth charter that constitutes guidelines for the design and conduct of youth sports programs. Adherence to the principles of the charter will enable communities to realize the several assets for young people that can be provided by the participation of youth in sports. Components of the charter include the following commitments to

- Make youth sports a priority for public funding and provide other forms of community support (space, facilities, volunteer coaches);

- Parents and coaches should emphasize standards of conduct as a primary goal of youth sports;

- Young people should be provided opportunities to participate in individual as well as team sports;

- Youth sports programs should encourage broad participation by ordinary players as well as stars; and

- Sports programs for youth must be carefully coordinated with other community events for young people. (Damon, 1997, pp. 123–125).

In sum, then, Damon and Gregory (in press) note that

The essential requirements of a youth charter are that 1) it must address the core matters of morality and achievement necessary for becoming a responsible citizen; and 2) it must focus on areas of common agreement rather than on doctrinaire squabbles or polarizing issues of controversy. A youth charter guides the younger generation towards fundamental moral virtues such as honesty, civility, decency, and the pursuit of benevolent purposes beyond the self. A youth charter is a moral and spiritual rather than a political document. (p. 13)

Consistent with the ideas of stage-environment fit discussed by Eccles and her colleagues (e.g., Eccles et al., 1991), Damon (1997) noted that embedding youth in a caring and developmentally facilitative community can promote their ability to develop morally and to contribute to civil society. For instance, in a study of about 130 African American parochial high school juniors, working at a soup kitchen for the homeless as part of a school-based community service program was associated with identity development and with the ability to reflect on society’s political organization and moral order (Yates & Youniss, 1996).