View sample personality in political psychology research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Political psychology “has a long past, but as an organized discipline, it has a short history,” wrote William F. Stone in The Psychology of Politics (Stone & Schaffner, 1988, p. v). Niccolò Machiavelli’s political treatise, The Prince (1513/1995), an early precursor of the field, has modern-day echoes in Richard Christie and Florence Geis’s Studies in Machiavellianism (1970). The formal establishment of political psychology as an interdisciplinary scholarly endeavor was anticipated by notable precursors in the twentieth century with a focus on personality, among them Graham Wallas’s Human Nature in Politics (1908); Harold Lasswell’s Psychopathology and Politics (1930) and Power and Personality (1948); Hans Eysenck’s The Psychology of Politics (1954); Fred Greenstein’s Personality and Politics (1969); and the Handbook of Political Psychology (1973) edited by Jeanne Knutson, who founded the International Society of Political Psychology in 1978.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The purpose of this research paper is to sketch the rich history of personality in political psychology, to take stock of the current state of personality-in-politics inquiry, and to map out new directions for this emerging application of personality theory informed by the rich possibilities of contextually adjacent scientific fields such as evolution.

The Emergence of Personality Inquiry in Political Psychology

In this research paper, the terms personality and politics are employed in Greenstein’s (1992) narrowly construed sense. Politics, by this definition, “refers to the politics most often studied by political scientists—that of civil government and of the extra-governmental processes that more or less directly impinge upon government, such as political parties” and campaigns. Personality, as narrowly construed in political psychology, “excludes political attitudes and opinions . . . and applies only to nonpolitical personal differences” (p. 107).

Origins of Personality-in-Politics Inquiry

Knutson’s 1973 Handbook, most notably the chapter “From Where and Where To?” by James Davies, defined the field at the time of its publication (Stone & Schaffner, 1988, p. v). Davies (1973) credits political scientist Charles Merriam of the University of Chicago with stimulating “the first notable liaisons between psychology and political science” (p. 18) in the 1920s and 1930s. Though Merriam did not personally exploit the fruitful possibilities he saw for a productive union of the two disciplines, his “intellectual progeny,” Harold Lasswell, “was the first to enter boldly into the psychological house of ill repute, establish a liaison, and sire a set of ideas and influences of great vitality” (p. 18).

Machiavelli’s famous treatise serves as testimony that, from the beginning, the study of personality in politics constituted an integral part of political-psychological inquiry. In the modern era, the tradition dates back to Sigmund Freud, who collaborated with William Bullitt on a psychological study of U.S. president Woodrow Wilson (Freud & Bullitt, 1967).

Types of Personality-in-Politics Inquiry

In examining the state of the personality-in-politics literature, Greenstein (1969) proposed three types of personalityin-politics inquiry: individual, typological, and aggregate.

Individual inquiry (Greenstein, 1969, pp. 63–93), which is idiographic in orientation, involves single-case psychological analyses of individual political actors. Although the singlecase literature historically comprised mostly psychological biographies of public figures, such as Alexander and Juliette George’s Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House (1956) and Erik Erikson’s Gandhi’s Truth (1969), it also encompassed in-depth studies of members of the general population, such as Robert Lane’s Political Ideology (1962). With increasing specialization in political psychology since the 1960s, the focus has shifted progressively to the psychological examination of political leaders, while single-case studies of ordinary citizens have become increasingly peripheral to the main focus of contemporary political personality research.

Typological inquiry (Greenstein, 1969, pp. 94–119), which is nomothetic in orientation, concerns multicase analyses of political actors. This line of inquiry encompasses the main body of work in political personality, including the influential work of Harold Lasswell (1930, 1948), James David Barber (1965, 1972/1992), Margaret Hermann (1974, 1980, 1986, 1987), and David Winter (1987, 1998) with respect to high-level political leaders; however, part of this literature focuses more on followers (i.e., mass politics) than on leaders (i.e., elite politics)—for example, Theodor Adorno, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford’s classic The Authoritarian Personality (1950) and Milton Rokeach’s The Open and Closed Mind (1960). Greenstein (1992) has submitted that typological study “is of potentially great importance: if political actors fall into types with known characteristics and propensities, the laborious task of analyzing them de novo can be obviated, and uncertainty is reduced about how they will perform in particular circumstances” (p. 120).

Aggregate inquiry (Greenstein, 1969, pp. 120–140) includes a large and diverse body of work on national character, conflict among nations, behavior in groups, and global psychologizing about humanity and society (pp. 15–16). Greenstein (1992) has written that the impact of mass publics on politics, except for elections and drastic shifts in public opinion, “is partial and often elusive,” in contrast to the political impact of leaders, which tends to be “direct, readily evident, and potentially momentous in its repercussions” (p. 122).

In his review of “Personality and Politics” in the Handbook of Personality (Pervin, 1990), Dean Keith Simonton (1990) observed that the psychometric examination of political leaders represents the leading edge of current personalityin-politics research (p. 671). Moreover, by 1990 the dominant paradigm in the psychological examination of leaders had undergone a shift from the earlier preponderance of qualitative, idiographic, psychobiographic analysis, to more quantitative and nomothetic methods—in other words, Greenstein’s (1969) typological inquiry. Simonton’s assessment is as valid now as it was more than a decade ago. Contemporary personality-in-politics inquiry focuses almost exclusively on the psychological examination of high-level political leaders and the impact of personal characteristics on leadership performance and policy orientation.

Its other principal avenue of inquiry, the study of ordinary citizens, has retreated from the political personality landscape, although it left a legacy of momentous works such asAdorno etal.(1950),Rokeach(1960),andothers.AsSimonton(1990) has noted, “the heyday of personality studies conducted on the typical citizen is past; the personality traits germane to citizen ideology and candidate pBibliography: have been inventoried many times” (p. 671). This trend represents a distinct shift from the personality-and-culture era of the 1940s and 1950s (McGuire, 1993), in which psychobiography, studies of national character, and research involving the authoritarian personality syndrome flourished (Levin, 2000, p. 605). In this regard, Greenstein (1992) pointed to “the vexed post–World War II national character literature in which often illdocumented ethnographic reports and cultural artifacts . . . were used to draw sweeping conclusions about modal national character traits,” with the result that by the 1950s, “there was broad scholarly consensus that it is inappropriate simply to attribute psychological characteristics to mass populations on the basis of anecdotal or indirect evidence” (p. 122). Accordingly, political personality inquiry became more leadership oriented in emphasis, with the study of followers (or mass publics) in the domain of political psychology increasingly shifting to cognate areas such as political socialization, political attitudes, prejudice and intergroup conflict, political participation, party identification, voting behavior, and public opinion, which could be studied more systematically than the impalpable notion of national character.

The Evolution of Personality Inquiry in Political Psychology

Political psychology, as much as any social-scientific endeavor, has evolved in sociohistoric context. Accordingly, the evolution of personality-in-politics inquiry in the second half of the twentieth century can be viewed against the backdrop of three defining events: the legacy of the Nazi Holocaust and World War II; the Cold War and the threat of nuclear annihilation; and the collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, with its attendant new world order.

The Postwar Era

The rise of Hitler and the Nazi Holocaust stimulated personality research in the areas of authoritarianism, belief systems, and ideology, as represented in the work of Adorno et al. (1950) and Rokeach (1960), noted previously—precisely the historical juncture that in the domain of social psychology stimulated vigorous research programs in conformity (e.g., Asch, 1955) and obedience (e.g., Milgram, 1963).

In a definitive 1973 review of research developments in political psychology since Lasswell (1951), Davies identified four distinct lines of inquiry in post–World War II political psychology: (a) the study of voting behavior in stable democracies, the dominant trend, which had become “increasingly dull, repetitious, and a precious picking of nits”; (b) crossnational comparative research in relatively stable, democratic polities (which included “the vexed post–World War II national character literature” noted by Greenstein, 1992, (p. 122); (c) the genesis of behavioral patterns established in childhood (i.e., political socialization), which, along with cross-national research, “provided some relief from the [dominant trend’s] rather static study of behavior under stable circumstances”; and (d) psychological political biography (p. 21). Concerning the latter, which is most closely allied to contemporary political personality inquiry, Davies (1973) noted the futility of attempting to ascertain the psychological determinants of why some individuals emerge as leaders, given the rudimentary nature of available conceptual tools and measuring devices. More useful, according to Davies, would be analysis and description of leadership style, which had become increasingly sophisticated, as evidenced by the work of Barber (1972–1992)—“the boldest step yet in establishing a typology applicable to all American presidents,” successfully making a case for “the predictability of. . . . how presidents will act” (Davies, 1973, p. 25).

The Cold War Era

By the 1960s, the Cold War, punctuated by the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, brought about an important shift in the direction of political personality research. In the shadow of the nuclear sword, the focus of interest shifted from the mass politics of followers to the elite politics of foreign-policy decision making. In social psychology, this trend was paralleled by research endeavors such as Charles Osgood’s (1962) explication of graduated reciprocation in tension-reduction (GRIT) and Irving Janis’s (1972/1982; Janis & Mann, 1977) influential work on groupthink and decision-making fiascoes. In his review of advances in the study of personality and politics, Greenstein (1992) noted that the 1970s and 1980s were marked by “burgeoning inquiry into political perception and cognitive psychology more generally” (p. 112), as represented by Robert Jervis’s (1976) text on threat perception and deterrence and Richard Lau and David Sears’s (1986) edited collection of papers on political cognition.

As a field, political psychology thrived in the sociohistoric environment of the Cold War, as witnessed by the publication of the Handbook of Political Psychology in 1973, with an important chapter on “Personality in the Study of Politics” by its editor, Jeanne Knutson; William F. Stone’s (1974) groundbreaking introductory political psychology textbook; and the founding of the International Society of Political Psychology in 1978. Greenstein, in his now classic Personality and Politics (1969), set about the task of clearing a path “through the tangle of intellectual underbrush” (Greenstein, 1987, p. v) of conflicting perspectives on whether personality in politics was amenable to, and worthy of, disciplined inquiry.

Well into the 1980s, however, three powerful influences would subdue the impact of Greenstein’s (1969) and Knutson’s (1973) important work in mapping out a conceptual framework conferring figural status upon the personality construct in the evolving study of personality in politics: the dominant interest in foreign-policy decision making against the backdrop of the Soviet-U.S. struggle for superpower supremacy; the cognitiverevolution(seeMcGraw,2000;Simon,1985),which extended its reach from its parent discipline of psychology into mainstream political science; and the person–situation debate (see Mischel, 1990) then raging in personality psychology.

In a preface to the new edition (1987) of Personality and Politics, Greenstein observed that “one kind of political psychology—the cognitive psychology of perception and misperception—has found a respected niche in a political science field, namely international relations” (p. vi). Ole Holsti (1989) asserted that the psychological perspective constituted a basic necessity in the study of international politics. As the 1980s drew to a close, Jervis (1989), in a paper outlining major challenges to the field of political psychology, wrote, “The study of individual personalities and personality types has fallen out of favor in psychology and political science, but this does not mean the topics are unimportant” (p. 491). Significantly, two decades earlier George (1969) and Holsti (1970) had published influential papers that revived the World War II–era operational code construct, in part because perception and beliefs were viewed as more easily inferred than personality—given “the kinds of data, observational opportunities, and methods generally available to political scientists” (George, 1969, p. 195).

The renewed focus on operational codes—beliefs about the fundamental nature of politics, which shape one’s worldview, and hence, one’s choice of political objectives—steered political personality in a distinctly cognitive direction. Stephen Walker (1990, 2000) and his associates (Dille & Young, 2000; Schafer, 2000) would carry this line of inquiry forward to the present day. Moreover, Hermann (1974) initiated a research agenda that accorded cognitive variables a prominent role in the study of political personality. Hermann’s (1980) conceptual scheme accommodated four kinds of personal characteristics hypothesized to play a central role in political behavior: beliefs and motives, which shape a leader’s view of the world, and decision style and interpersonal style, which shape the leader’s personal political style. Hermann’s model warrants particular attention because of the degree to which it integrated existing perspectives at the time, and because of its enduring influence on the study of personality in politics.

Conceptually, Hermann’s notion of beliefs is anchored to the philosophical beliefs component of the operational code construct. Her interest in motives stems from Lasswell’s Power and Personality (1948) and Winter’s The Power Motive (1973)—an approach to political personality that Winter (1991) would elaborate into a major political personality assessment methodology in its own right. Hermann’s construal of decision style overlaps with the instrumental beliefs component of George’s (1969) operational code construct and aspects of Barber’s (1972/1992) formulation of presidential character, focusing particularly on conceptual complexity (see Dille & Young, 2000)—once again, an approach to political personality that would later develop into a major branch of political personality assessment, as represented in the work of Suedfeld (1994) on integrative complexity. Finally, Hermann’s interpersonal style domain encompasses a number of politically relevant personality traits such as suspiciousness, Machiavellianism, and task versus relationship orientation in leadership (see Hermann, 1980, pp. 8–10).

Methodologically, a common strand of cognitively and motivationally oriented trait approaches—such as those of Hermann (1987), Suedfeld (1994), Walker (1990), and Winter (1998)—is their reliance on content analysis of public documents (typically speeches and other prepared remarks or interviews and spontaneous remarks) for the indirect assessment of political personality (see Schafer, 2000, for a recent overview of issues in at-a-distance methods of psychological assessment).

As Simonton (1990) has noted, “The attributes of character that leave the biggest impression on political affairs involve both cognitive inclinations, which govern how an individual perceives and thinks about the world, and motivational dispositions, which energize and channel individual actions in the world” (pp. 671–672). Hermann’s model, in capturing cognition (including beliefs or attitudes) and motivation (recognizing the importance of affect in politics and checking the tendency in political psychology toward overemphasis of human rationality), clearly fills Simonton’s prescription. On the other hand, Hermann’s construal of decision style as a personality (or input) variable is problematic. Renshon’s (1996b) integrative theory of character and political performance, for example, specifies political and policy judgments and decision making, along with leadership, as performance (output) variables. Finally, Hermann’s construal of personality in terms of interpersonal style is too restrictive for a comprehensive theory of personality in politics.

The New World Order

Epochal events such as the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapse of communist rule in Central and Eastern Europe in 1989–1990, the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991–1992, South Africa’s transition from apartheid state to nonracial democracy in 1994 following Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990, and the Persian Gulf War in 1991 marked the beginning of a new world order, which stimulated renewed research interest in psychometric inquiry—an area that contemporaneously began to emerge as a new paradigm for the study of personality in politics (Immelman, 1988, 1993; Simonton, 1990). In psychometric personality-inpolitics inquiry, standard psychometric instruments were adapted to “derive personality measures from biographical dataratherthanthroughcontentanalysisofprimarymaterials” (Simonton, 1990, p. 678), although some investigators (e.g., Kowert, 1996; Rubenzer, Faschingbauer, & Ones, 2002), though similar in intent, opted for indirect expert ratings instead of direct analysis of biographical data. The focus of psychometric inquiry is less on cognitive variables and foreign-policy decision making and more on a personological understanding of the person in politics, his or her personality attributes, and the implications of personality for leadership performance and generalized policy orientation.

George and George’s (1956) psychoanalytically framed study of Woodrow Wilson, which relied on clinical insights rather than psychometric evaluation of biographical data, is the best known precursor of the personological trend in political personality research. In Simonton’s (1990) judgment, qualitative, nonpsychometric psychobiographical analyses “have leaned heavily on both theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches that cannot be considered a central current in mainstream personality research” (p. 671). Although some highly informative personological studies (e.g., Glad, 1996; Post, 1991; Renshon, 1996a, 1998) continued in the older psychobiographic tradition, the twentieth century closed with a distinct shift in a psychometric direction (Immelman, 1998, 2002; Kowert, 1996; Lyons, 1997; Rubenzer et al., 2002).

Although some contemporary psychobiographically oriented studies are theoretically eclectic (e.g., Betty Glad’s 1996 study of the transfer of power from Gorbachev to Yeltsin in Russia and from De Klerk to Mandela in South Africa), the modern psychoanalytic reformulations of Heinz Kohut (1971, 1977) and Otto Kernberg (1984) have acquired considerable cachet in political psychology. Swansbrough (1994), for instance, conducted a Kohutian analysis of George Bush’s personality and leadership style in the Persian Gulf war. Similarly, Stanley Renshon’s (1996a) psychobiography of Bill Clinton is informed primarily by Kohutian self psychology. Jerrold Post’s (1991) psychobiographical analysis of Saddam Hussein is more indebted to Kernberg’s notion of narcissistic personality organization (see Post, 1993). Despite Simonton’s (1990) grim prognostication and Jervis’s (1989) observation that “Freudian analysis and psychobiographies are out of fashion” (p. 482), the psychobiographic tradition has been revitalized by the analytic insights of scholars such as Post and Renshon.

Obstacles to the Advancement of the Personality-In-Politics Enterprise

Greenstein (1992) has formulated what may be the most concise statement of the case for studying personality in politics: “Political institutions and processes operate through human agency. It would be remarkable if they were not influenced by the properties that distinguish one individual from another” (p. 124). Yet, specialists in the study of politics “tend to concentrate on impersonal determinants of political events and outcomes” or define away personal characteristics, “positing rationality . . . and presuming that the behavior of actors can be deduced from the logic of their situation” (p. 106). The relevance of the study of personality with respect to political leadership is nicely captured in Renshon’s (1996b) contention that

many of the most important aspects of presidential performance rely on the personal characteristics and skills of the president. . . . It is his views, his goals, his bargaining skills . . . , his judgments, his choices of response to arising circumstance that set the levers of administrative, constitutional, and institutional structures into motion. (p. 7)

In this regard, Glad (1996), writing about the collapse of the communist state in the Soviet Union and the apartheid state in South Africa, has shown convincingly that the personal qualities of leaders can play a critical role at turning points in history.

Scholarly Skepticism and Inadequate Conceptual and Methodological Tools

Despite the conviction of personality-in-politics practitioners in the worth of their endeavor, the study of personality in politics is not without controversy (see Lyons, 1997, pp. 792– 793, for a concise review of “controversies over the presidential personality approach”). Greenstein (1969, pp. 33–62) offered an incisive critique of “two erroneous” and “three partially correct” objections to the study of personality in politics, lamenting that the study of personality in politics was “not a thriving scholarly endeavor,” principally because “scholars who study politics do not feel equipped to analyze personality in ways that meet their intellectual standards. . . . [thus rendering it primarily] the preserve of journalists” (p. 2). The optimistic verdict more than three decades later is that political personality has taken root and come of age as a scholarly endeavor.

Inadequate Transposition From Source to Target Discipline

Although the enterprise of studying personality in politics has largely succeeded in countering common objections to its usefulness, it has been hampered by inadequate transposition from the source discipline of personality assessment to the target discipline of political psychology. For political personality inquiry to remain a thriving scholarly endeavor and have an impact beyond the narrow confines of academic political psychology, it will need to account, at a minimum, for the patterning of personality variables “across the entire matrix of the person” (Millon & Davis, 2000, pp. 2, 65). Only then will political personality assessment provide an adequate basis for explaining, predicting, and understanding political outcomes. Moreover, political personologists will need to advance an integrative theory, not only of personality and of political leadership, but also of the personality-politics nexus. In The Psychological Assessment of Presidential Candidates (1996b), Stanley Renshon provides a partial blueprint for this daunting task.

Inadequate Progress From Description of Observable Phenomena to Theoretical Systematization

Ultimately, scholarly progress in personality-in-politics inquiry hinges on its success in advancing from the “natural history stage of inquiry” to a “stage of deductively formulated theory” (Northrop, 1947). The intuitive psychologist’s “ability to ‘sense’ the correctness of psychological insight” presents an easily overlooked obstacle to progress in political-personological inquiry. Early in the development of a scientific discipline, according to philosopher of science Carl Hempel (1965), investigators primarily strive “to describe the phenomena under study and to establish simple empirical generalizations concerning them,” using terms that “permit the description of those aspects of the subject matter which are ascertainable fairly directly by observation” (p. 140). Hermann’s (1974, 1980) early work illustrates this initial stage of scientific development. In the words of Hempel (1965),

The shift toward theoretical systematization is marked by the introduction of new, “theoretical” terms, which refer to various theoretically postulated entities, their characteristics, and the processes in which they are involved; all of these are more or less removed from the level of directly observable things and events. (p. 140)

Hermann’s (1987) proposal of a model suggesting how leaders’ observable personal characteristics “link to form role orientations to foreign affairs” (p. 162) represents considerable progress in this direction; however, it lacks systematic import.

A Lack of Systematic Import

Theoretical systematization and empirical import (operational definitions) are necessary but not sufficient for scientific progress.

To be scientifically useful a concept must lend itself to the formulation of general laws or theoretical principles which reflect uniformities in the subject matter under study, and which thus provide a basis for explanation, prediction, and generally scientific understanding. (Hempel, 1965, p. 146)

The most striking instance of this principle of systematic import, according to Hempel (1965), “is the periodic system of the elements, on which Mendeleev based a set of highly specific predictions, which were impressively confirmed by subsequent research” (p. 147). Hempel chronicled similar scientific progress in biological taxonomic systems, which proceeded from primitive classification based on observable characteristics to a more advanced phylogenetic-evolutionary basis. Thus, “two phenomenally very similar specimens may be assigned to species far removed from each other in the evolutionary hierarchy, such as the species Wolf (Canis) and Tasmanian Wolf (Thylacinus)” (Hempel, 1965, p. 149).

For personality-in-politics inquiry to continue advancing as a scholarly discipline, it will have to come to grips with the canon of systematic import. At base, this means that theoretical systematizations cannot be constructed on the foundation of precisely those personal characteristics from which they were originally inferred. As Kurt Gödel (1931) demonstrated with his incompleteness theorem, no self-contained system can prove or disprove its own propositions while operating within the axioms of that system.

Toward a Generative Theory of Personalityand Political Performance

Ideally, conceptual systems for the study of political personality should constitute a comprehensive, generative, theoretically coherent framework consonant with established principles in the adjacent sciences, congenial with respect to accommodating a diversity of politically relevant personal characteristics, and capable of reliably predicting meaningful political outcomes. In this regard, Renshon (1996b) is critical of unitary trait theories of political personality (such as those relying primarily on isolated personality variables, motives, or cognitive variables), noting that “it is a long causal way from an individual trait of presidential personality to a specific performance outcome” and that unitary trait theories fail to contribute to the development of an integrated psychological theory of leadership performance. He ventures that “more clinically based theories . . . might form the basis of a more comprehensive psychological model of presidential performance” (p. 11).

The problem bedeviling contemporary personality-inpolitics inquiry, however, is more profound than the precarious perch of leadership performance theories on a fragmented personological foundation. In his critique of postwar research directions in political psychology, Davies (1973) declared:

There is . . . a kind of atrophy of theory and research that can help us link observable acts with their deeply and generally antecedent causes in the human organism, notably the nervous and endocrine systems. Aristotle sought such relationships. So did Hobbes, whose Leviathan (1651) founded its analysis of political institutions on a theory of human nature. And likewise, Lasswell has sought to relate fundamental determinants to observable effects—and vice versa. (p. 26)

Similarly, but with greater theoretical precision, Millon (1990), in explicating his evolutionary theory of personality, distinguished between “true, theoretically deduced” nosologies and those that provide “a mere explanatory summary of known observations and inferences” (p.105). He cited Hempel (1965), who proposed that scientific classification ought to have an “objectiveexistence in nature,…‘carving nature at the joints,’ in contradistinction to ‘artificial’ classifications, in which the defining characteristics have few explanatory or predictive connections with other traits” (p. 147). Ultimately, “in the course of scientific development, classifications defined by reference to manifest, observable characteristics will tend to give way to systems based on theoretical concepts” (Hempel, 1965, pp. 148–149).

Greenstein (1987), pointing to the work of Gangestad and Snyder (1985) and Morey (1985), acknowledged the substantial progress since the publication of his seminal Personality and Politics (1969) “in grounding complex psychological typologies empirically,” yet pessimistically proclaimed that “complex typologies are not easily constructed and documented” (Greenstein, 1987, p. xiv). Although Greenstein was clearly correct on both counts, he failed to report that these typologies had already been constructed and empirically documented (see, for example, Millon, 1986). Greenstein’s (1987) conclusion, that the difficulty of constructing a complex typology renders it “productive to classify political actors in terms of single traits that differentiate them in illuminating ways” (p. xiv), is therefore patently founded on a false premise. This pitfall of overlooking parallel developments in clinical science is reminiscent of Barber’s (1972/1992) construction, de novo, of a rudimentary 2 × 2 model for assessing presidential character, which yields little more systematic import or prototypal distinctiveness than the humoral doctrine of Hippocrates, 24 centuries earlier.

Toward a Politically Relevant Theory of Personality in Politics

Renshon (1996b) has argued persuasively that a president’s character serves as the foundation for leadership effectiveness, in part because political parties (in the United States) have lost much of their ability to serve as “filters” for evaluating candidates, who are no longer mere standard-bearers of party platforms and ideologies (pp. 38–40). Renshon examines the psychology of presidential candidates using theories of character and personality, theories of presidential leadership and performance, and theories of public psychology. For a concise, schematic outline of Renshon’s model, which is anchored to Kohut’s (1971, 1977) psychoanalytic self theory, the reader is referred to appendix 2 (pp. 409–411) of his book, The Psychological Assessment of Presidential Candidates (1996b).

For the great majority of psychodiagnosticians, who are more familiar with Axis II of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association (APA; 1994) than with Kohutian self psychology as a framework for recording personality functioning, Renshon’s (1996b) particular clinically based theory of political personality may be somewhat restrictive, if not arcane. Fortunately, the value of Renshon’s work with respect to mapping out an integrated theory of character and leadership for political personality assessment is not contingent upon the utility of the personological component of his model; it can easily be molded to the theoretical proclivities of the practitioner, including—perhaps especially— those favoring a theoretical orientation more compatible with the DSM-IV.

Toward a Psychologically Grounded Theory of Political Performance

In developing a psychologically grounded theory of political performance, Renshon (1996b) distinguished between two key elements of presidential role performance: “making good policy and political decisions” and “pursuing and realizing policy purposes” (p. 12). With regard to the former, Renshon (1996b) proposed a model of judgment and decision making (pp. 206–223, 411) capable of accommodating those cognitive constructs that became popular in Cold War–era political psychology (e.g., integrative complexity). Concerning the second aspect of political performance, Renshon (1996b) proposes “three distinct aspects” (p. 226) of political leadership shaped by character: mobilization, the ability to arouse, engage, and direct the public; orchestration, the organizational skill and ability to craft specific policies; and consolidation, the skills and tasks required to preserve the supportive relationships necessary for implementing and institutionalizing one’s policy judgments (pp. 227, 411).

However, those seeking to develop a generative theory of personality and political performance confront a conceptual minefield—a problem highlighted previously with respect to the overly restrictive, psychodynamically framed character component of Renshon’s model, which limits its integrative potential. This issue is examined more closely in the next section.

Conceptual Problems in the Study of Personality in Politics

Unresolved conceptual problems that cloud personality-inpolitics inquiry include a lack of agreement about the appropriate levels of analysis; a lack of clarity about the requisite scope of inquiry; theoretical stagnation; and a failure of some approaches to satisfy basic standards for operationalizing the personality construct.

Levels of Analysis

In his early efforts to chart a course for the field’s development, Greenstein (1969) noted that the personality-in-politics literature was “formidably gnarled—empirically, methodologically, and conceptually” (p. 2). He identified three operational levels for the assessment of personality in politics: phenomenology, dynamics, and genesis. In Greenstein’s opinion, these distinctions are useful

for sorting out the different kinds of operations involved in the psychological diagnosis of political actors, and for ordering diagnostic operations in terms of both the directness of their bearing on explanations of political action and the degree to which they can be carried out in a more or less standardized fashion. (p. 144)

Phenomenology—regularities in the observable behavior of political actors—according to Greenstein, is “the most immediately relevant supplement to situational data in predicting and explaining the actor’s behavior” (p. 144), whereas explanations of genesis are “remote from the immediate nexus of behavior” and pose “difficult questions of validation” (p. 145). With the increasing dominance of descriptive approaches and the dwindling influence of psychoanalysis in contemporary personality assessment (Jervis, 1989, p. 482; Simonton, 1990, p. 671), preoccupation with personality dynamics can be expected to wane, while psychogenesis already occupies a peripheral role in political personality, of primary interest to psychohistorians.

Millon’s (1990) evolutionary model refines Greenstein’s three operational levels of analysis (phenomenology, dynamics, and genesis) by redefining genesis as a conceptual construct, relabeling dynamics as the intrapsychic level of analysis, disaggregating phenomenology into phenomenological and behavioral data levels, and adding a fourth, biophysical, data level.

The critical operational constructs are the clinical domains (or personality attributes), which provide an explicit basis for personality assessment. Millon’s (1990) evolutionary model specifies four structural domains (object representations, self-image, morphologic organization, and mood or temperament) and four functional domains (expressive behavior, interpersonal conduct, cognitive style, and regulatory mechanisms) encompassing four data levels: behavioral (expressive behavior, interpersonal conduct); phenomenological (cognitive style, object representations, self-image); intrapsychic (regulatory mechanisms, morphological organization); and biophysical (mood or temperament).

Scope of Inquiry

Beyond simply refining Greenstein’s (1969) specification of operational levels for personality-in-politics inquiry, the scope of this endeavor must be elucidated if political personality is to extricate itself from the “tangled underbrush.” The requisite scope of inquiry is implied in the organizational framework of a representative undergraduate personality text (Pervin & John, 2001), which presents theory and research in terms of structure, process, development, psychopathology, and change—a formulation consistent with the organizing framework of structure, dynamics, development, assessment, and change that Gordon Allport employed in his seminal text, Personality: A Psychological Interpretation (1937). Millon’s (1990, 1996) contemporary clinical model of personality follows this time-honored tradition by construing personality in terms of its structural and functional domains, normal and pathological variants, developmental background (including hypothesized biogenic factors and characteristic developmental history), homeostatic (self-perpetuation) processes, and domain-based modification strategies and tactics.

Theoretical Orientation

In an important recapitulation nearly a quarter-century after his landmark work in Personality and Politics (1969), Greenstein (1992) resolved, “The study of personality and politics is possible and desirable, but systematic intellectual progress is possible only if there is careful attention to problems of evidence, inference, and conceptualization” (p. 105). He went on to assert, however, that “it is not appropriate to recommend a particular personality theory,” suggesting that the theories of “Freud, Jung, Allport, Murray, and . . . many others” (p. 117) are all potentially useful. Although there is merit in Greenstein’s (1973) counsel to “let many flowers bloom” (p. 469), professional psychodiagnosticians—who tend not to treat the classic schools of personality theory as templates for tailoring their assessment tools—might find this assertion quite striking. Burgeoning scientific and technological progress in clinical science over the past halfcentury practically dictates that assimilating contemporary approaches to psychodiagnostics and personality assessment provides a less obstacle strewn passage for personality-inpolitics practitioners than steering a course illuminated solely by the radiance of the great pioneers of personality theory. Despite major advances in behavioral neuroscience, evolutionary ecology, and personality research in the past two decades, personalityin-politics inquiry arguably has become insular and stagnant, with few fresh ideas and—with the exception of cognitive science—little indication of meaningful cross-pollination of ideas from adjacent disciplines.

Necessary Conditions for Operationalizing Research Designs

In the original Handbook of Political Psychology (1973), Knutson implored that, to be feasible for studying personality in politics, conceptual models should fulfill three critical requirements for operationalizing research designs in political personality: Clearly conceptualize the meaning of the term personality; delineate attributes of personality that can be quantified or objectively assessed, thereby rendering them amenable to scientific study; and specify how the personality attributes subjected to scientific inquiry relate to the personality construct (pp. 34–35). As shown next, Millon’s (1990, 1996) evolutionary model of personality satisfies all three of Knutson’s criteria, making it eminently useful for studying personality in politics.

Defining Personality

From Millon’s evolutionary-ecological perspective, personality constitutes ontogenetic, manifest, adaptive styles of thinking, feeling, acting, and relating to others, shaped by interaction of latent, phylogenetic, biologic endowment and social experience. This construal is consistent with the contemporary view of personality as

a complex pattern of deeply embedded psychological characteristics that are largely nonconscious and not easily altered, expressing themselves automatically in almost every facet of functioning. Intrinsic and pervasive, these traits emerge from a complicated matrix of biological dispositions and experiential learnings, and ultimately comprise the individual’s distinctive pattern of perceiving, feeling, thinking, coping, and behaving. (Millon, 1996, p. 4)

Delineating the Core Attributes of Personality

In constructing an integrated personality framework that accounts for “the patterning of characteristics across the entire matrix of the person” (Millon & Davis, 2000, p. 2), Millon (1994b) favors a theoretically grounded “prototypal domain model” (p. 292) that combines quantitative dimensional elements (e.g., the five-factor approach) with a qualitative categorical approach (e.g., DSM-IV). The categorical aspect of Millon’s model is represented by eight universal attribute domains relevant to all personality patterns, namely expressive behavior, interpersonal conduct, cognitive style, mood or temperament, self-image, regulatory mechanisms, object representations, and morphologic organization.

Assessing Personality on the Basis of Variability Across Attributes

Millon specifies prototypal features (diagnostic criteria) within each of the eight attribute domains for each personality style (Millon, 1994a; Millon & Everly, 1985) or disorder (1990, 1996) accommodated in his taxonomy. The dimensional aspect of Millon’s schema is achieved by evaluating the “prominence or pervasiveness” (1994b, p. 292) of the diagnostic criteria associated with the various personality types.

Additional Considerations

Traditionally, political personality assessment has borne little resemblance to the conceptualization of personality shared by most clinically trained professional psychodiagnosticians, or to their psychodiagnostic procedures. In satisfying Knutson’s three criteria, Millon’s personological model offers a viable integrative framework for a variety of current approaches to political personality, thus narrowing conceptual and methodological gaps between existing formulations in the source disciplines of personology and personality assessment and the target discipline of contemporary political personality— specifically the psychological examination of political leaders.

Although necessary for operationalizing research designs, Knutson’s (1973) three criteria provide an insufficient basis for applied personality-in-politics modeling. A theoretically sound, comprehensive, useful personality-in-politics model with adequate explanatory power and predictive utility must meet additional standards. I propose the following basic standards for personality-in-politics modeling:

- The meaning of the term personality should be clearly defined.

- Quantifiable personality attributes amenable to objective assessment should be clearly specified.

- The personality attributes subject to inquiry should be explicitly related to the personality construct as whole.

- The conceptual model for construing personality in politics should be congruent with personality systems employed with reference to the general population.

- The conceptual model for construing political personality should be integrative, capable of accommodating diverse, multidisciplinary perspectives on politically relevant personal characteristics.

- The conceptual model should offer a unified view of normality and psychopathology.

- The conceptual model should be rooted in personality theory, with clearly specified referents in political leadership theory.

- The personality-in-politics model should be embedded in a larger conceptual framework that acknowledges cultural contexts and the impact of distal and proximal situational determinants that interact with dispositional variables to shape political behavior.

- The methodology for assessing political personality should be congruent with standard psychodiagnostic procedures in conventional clinical practice.

- The assessment methodology should be inferentially valid.

- The assessment methodology should meet acceptable standards of evidence for reliability.

- For purposes of predictive utility, the assessment methodology should be practicable during political campaigns.

- For considerations of efficiency, the assessment methodology should be minimally cumbersome or unwieldy.

- For optimal utility, the assessment methodology should be remote, indirect, unobtrusive, and nonintrusive.

- For advancing theoretical systematization, the conceptual model should be nomothetically oriented, permit typological inquiry, and posit a taxonomy of political personality types.

A Personality-In-Politics Agenda for the New Century

In the new world order of the twenty-first century, personality-in-politics inquiry is poised to reclaim personality as the central organizing principle in the study of political leadership, informed by insights garnered from the cognitive revolution preceding the close of the twentieth century and energized by the quickening evolutionary reconceptualization of personology at the dawn of the new millennium.

From Cognitive Revolution to Evolutionary Psychology

On the crest of major breakthroughs in evolutionary biology during the preceding quarter-century, the emerging evolutionary perspective in psychology since the mid-1980s (see Buss, 1999; Millon, 1990) represents the first major theoretical shift in the discipline since the cognitive revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. Conceptually, the integrative capacity of Millon’s (1990) evolutionary model renders it sufficiently comprehensive to accommodate major tenets of psychodynamic, behavioral, humanistic, interpersonal, cognitive, biogenic, and trait approaches to personality. Methodologically, Millon’s framework provides an empirically validated taxonomy of personality patterns compatible with the syndromes described in DSM-IV, Axis II (APA, 1994).

No present conceptual system in the field of political personality rivals Millon’s model in compatibility with conventional psychodiagnostic methods and standard clinical practice in personality assessment. Moreover, no current system matches the elegance with which Millon’s evolutionary model synthesizes normality and psychopathology. In short, Millon offers a theoretically coherent alternative to existing conceptual frameworks and assessment methodologies for the psychological examination of political leaders (see Post, 2003, for an up-to-date collection of current conceptualizations; see Kinder, 1999, for a series of reviews, both critical and laudatory, of “Millon’s evolving personality theories and measures”).

The Utility of Millon’s Model as a Generative Framework for the Study of Personality in Politics

The work of Millon (1990, 1994a, 1996; Millon & Davis, 2000; Millon, Davis, & Millon, 1996; Millon & Everly, 1985) provides a sound foundation for conceptualizing and assessing political personality, classifying political personality types, and predicting political behavior.

Epistemologically, it synthesizes the formerly disparate fields of psychopathology and normatology and formally connects them to broader spheres of scientific knowledge, most notably their foundations in the natural sciences. Diagnostically, it offers an empirically validated taxonomy of personality patterns congruent with the syndromes described on Axis II of DSM-IV (APA, 1994), thus rendering it compatible with conventional psychodiagnostic procedures and standard clinical practice in personality assessment.

Millon (1986) uses the concept of the personality prototype (paralleling the medical concept of the syndrome) as a global formulation for construing and categorizing personality systems, proposing that “each personality prototype should comprise a small and distinct group of primary attributes that persist over time and exhibit a high degree of consistency” (p. 681). To Millon, the essence of personality categorization is the differential identification of these enduring (stable) and pervasive (consistent) primary attributes.This position is consistent with the conventional view of personality in the study of politics (see Knutson, 1973, pp. 29–38). In organizing his attribute schema, Millon (1986) favors “an arrangement that represents the personality system in a manner similar to that of the body system, that is, dividing the components into structural and functional attributes” (p. 681; see Millon, 1990, pp. 134–135, for a concise summary of these attribute domains).

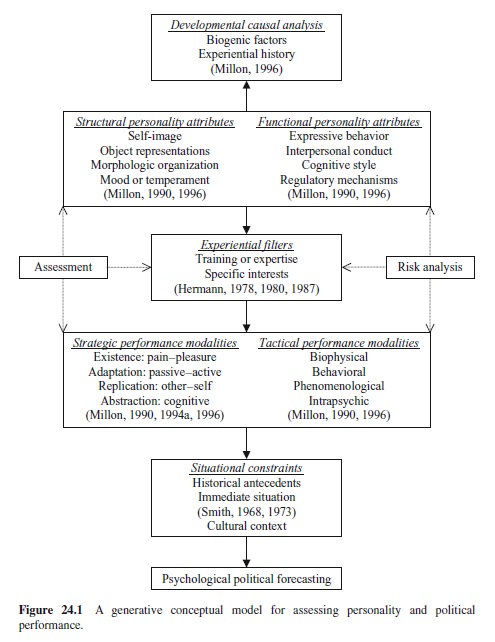

The Core Characteristics of a Comprehensive Model of Personality in Politics

A comprehensivemodelforthestudyofpersonalityinpolitics (see Figure 24.1) should account for structural and functional personality attributes, at behavioral, phenomenological, intrapsychic, and biophysical levels of analysis; permit supplementary developmental causal analysis (i.e., genesis or etiology);provideanexplicitframeworkforriskanalysis(i.e., account for normal variability as well as personality pathology); and provide an assessment methodology. Furthermore, the personality model should be linked with performanceoutcomes,recognizetheimpactofsituationalvariables and the cultural context on political performance, and allow for personological, situational, and contextual filters that may modulate the impact of personality on political performance.

Structural Attributes of Personality

Structural attributes, according to Millon (1990), “represent a deeply embedded and relatively enduring template of imprinted memories, attitudes, needs, fears, conflicts, and so on, which guide the experience and transform the nature of ongoing life events” (p. 147). Millon (1986, 1990) has specified four structural attributes of personality, outlined in the following subsections. Where relevant, equivalent or compatible formulations in the field of political psychology are noted.

Self-Image

Self-image, located at the phenomenological level of analysis, denotes a person’s perception of self-as-object or the manner in which people overtly describe themselves (Millon, 1986; 1990, pp. 148–149).

This domain accommodates self-confidence, an element of decision style in Hermann’s (1980, 1987) conceptual scheme. It also offers an alternative theoretical basis for construing Renshon’s (1996b) character domain of ambition, derived from Kohut’s (1971, 1977) psychoanalytic self theory.

Object Representations

The domain of object representations, located at the phenomenological level of analysis, encompasses the inner imprint left by a person’s significant early experiences with others—in other words, the structural residue of significant past experiences, composed of memories, attitudes, and affects, which servesasasubstrateofdispositionsforperceivingandresponding to the social environment (Millon, 1986, 1990, p. 149).

This domain accommodates Renshon’s (1996b) character attribute of relatedness, which is steeped in object-relations theory, including Kohut’s (1971) selfobject construct and Karen Horney’s (1937) interpersonal tendencies.

Morphologic Organization

Morphologic organization, located at the intrapsychic level of analysis, embodies the overall architecture that serves as framework for a person’s psychic interior—the structural strength, interior congruity, and functional efficacy of the personality system (Millon, 1986, 1990, pp. 149, 157).

This domain, roughly equivalent to the notion of ego strength, provides a good fit for Renshon’s (1996b) realm of character integrity, derived from Kohut’s (1971) self theory and elaborated in terms of Erikson’s (1980) notions of ego identity and ego ideal.

Mood or Temperament

Mood or temperament, located at the biophysical level of analysis, captures a person’s typical manner of displaying emotion and the predominant character of an individual’s affect, and the intensity and frequency with which he or she expresses it (Millon, 1986, 1990, p. 157).

This domain provides a suitable fit for Barber’s (1972/1992) construal of presidential character along positive–negative (i.e., affective) and active–passive (i.e., predisposition to activity, or temperamental) dimensions. In conjunction with the domain of cognitive style, mood or temperament also provides a conceptual frame of reference for the so-called pessimistic explanatory style of stable (vs. unstable), global (vs. specific), and internal (vs. external) causal attribution with respect to adversity, which, in combination with excessive rumination about problems, has been shown to predict not only susceptibility to helplessness and depression, but the electoral defeat of presidential candidates (Zullow & Seligman, 1990).

Functional Attributes of Personality

Functional attributes, according to Millon (1990), “represent dynamic processes that transpire within the intrapsychic world and between the individual’s self and psychosocial environment” (p. 136). Millon (1986, 1990) has specified four functional attributes of personality, outlined in the next sections. Where relevant, equivalent or compatible formulations in the field of political psychology are noted.

Expressive Behavior

Expressive behavior, located at the behavioral level of analysis, refers to a person’s characteristic behavior—how the individual typically appears to others and what the individual knowingly or unknowingly reveals about him- or herself or wishes others to think or to know about him or her (Millon, 1986, 1990, p. 137).

Numerous personality traits commonly used to describe political behavior are accommodated by this domain, including assertiveness, confidence, competence, arrogance, suspiciousness, impulsiveness, prudence, and perfectionism.

Interpersonal Conduct

Interpersonal conduct, located at the behavioral level of analysis, includes a person’s typical style of interacting with others, the attitudes that underlie, prompt, and give shape to these actions, the methods by which the individual engages others to meet his or her needs, and the typical modes of coping with social tensions and conflicts (Millon, 1986, 1990, pp. 137, 146).

This domain accommodates the personal political characteristic of interpersonal style in Hermann’s (1980, 1987) conceptual scheme, including its two operational elements, distrust of others and task orientation. The domain of interpersonal conduct also offers a conceptual niche for Christie and Geis’s (1970) operationalization of Machiavellianism, which remains popular as a frame of reference for describing political behavior.

Cognitive Style

Cognitive style, located at the phenomenological level of analysis, signifies a person’s characteristic manner of focusing and allocating attention, encoding and processing information, organizing thoughts, making attributions, and communicating thoughts and ideas (Millon, 1986, 1990, p. 146).

This domain accommodates the personal political characteristics of beliefs and decision style in Hermann’s (1980, 1987) framework, most notably the conceptual complexity component of decision style, and integrative complexity (e.g., Suedfeld & Tetlock, 1977; Tetlock, 1985), which rose to prominence during the Cold War era as a major construct for operationalizing personality in politics. The domain of cognitive style is also compatible with the notions of nationalism and belief in one’s own ability to control events (the two key operational elements of beliefs in Hermann’s conceptual framework) and her operationalization of several beliefs associated with contemporary reformulations of the operational code construct (George, 1969; Holsti, 1970; Walker, 1990), such as belief in the predictability of events and belief in the inevitability of conflict.

Regulatory Mechanisms

The domain of regulatory mechanisms, located at the intrapsychic level of analysis, involves a person’s characteristic mechanisms of self-protection, need gratification, and conflict resolution (Millon, 1986, 1990, pp. 146–147).

The need-gratification facet of the regulatory mechanisms domain provides a potential fit for Winter’s (1973, 1987, 1991, 1998) approach to political personality, which emphasizes needs for power, achievement, and affiliation, and for the related motives aspect of the personal characteristics component of Hermann’s (1980, 1987) conceptual scheme.

Personality Description, Psychogenetic Understanding, and Predictive Power

The practical value of conceptual systems for assessing personality in politics is proportionate to their predictive utility in anticipating political behavior. Moreover, there is considerable merit in a personality model’s capacity to promote accurate understanding of the developmental antecedents of political personality patterns.

Developmental Causal Analysis

The importance of a developmental component in a comprehensive model of personality is implicit in Millon and Davis’s (2000) contention that, “once the subject has been conceptualized in terms of personality prototypes of the classification system, biographical information can be added” to answer questions about the origin and development of the subject’s personality characteristics (p. 73). Greenstein (1992) cautions against “the fallacy of observing a pattern of behavior and simply attributing it to a particular developmental pattern, without documenting causality, and perhaps even without providing evidence that the pattern existed” (p. 121).

Millon (1996) frames developmental causal analysis in terms of hypothesized biogenic factors and the subject’s characteristic developmental history. For the majority of present-day personality-in-politics investigators, who generally favor a descriptive approach to personality assessment, developmental questions are of secondary relevance; however, an explicit set of developmental relational statements is invaluable for psychobiographically oriented analysis. Moreover, precisely because each personality pattern has characteristic developmental antecedents, in-depth knowledge of a subject’s experiential history can be useful with respect to validating the results of descriptive personality assessment, or for suggesting alternative hypotheses (Millon & Davis, 2000, p. 74). This benefit notwithstanding, genetic reconstruction does not constitute an optimal basis for personality assessment and description.

A Framework for Risk Analysis

As Sears (1987) has noted, a problem with existing conceptualizations of personality in politics is the dichotomy between pathology-oriented and competence-oriented analyses. Millon’s evolutionary theory of personality bridges the gap by offering a unified view of normality and psychopathology: “No sharp line divides normal from pathological behavior; they are relative concepts representing arbitrary points on a continuum or gradient” (Millon, 1994b, p. 283). The synthesis of normality and pathology is an aspect of Millon’s principle of syndromal continuity, which holds, in part, that personality disorders are simply “exaggerated and pathologically distorted deviations emanating from a normal and healthy distribution of traits” (Millon & Everly, 1985, p. 34). Thus, whereas criteria for normality include “a capacity to function autonomously and competently, a tendency to adjust to one’s environment effectively and efficiently, a subjective sense of contentment and satisfaction, and the ability to actualize or to fulfill one’s potentials” (Millon, 1994b, p. 283), the presence of psychopathology is established by the degree to which a person is deficient, imbalanced, or conflicted in these areas.

At base, then, Millon (1994b) regards pathology as resulting “from the same forces . . . involved in the development of normal functioning . . ., [the determining influence being] the character, timing, and intensity” (p. 283) of these factors (see also Millon, 1996, pp. 12–13). From this perspective, risk analysis would entail the classification of individuals on a range of dimensions, each representing a normal-pathological continuum.

Despite the emphasis of Millon’s (1996) clinical model on personality disorders, the absence of a conceptual distinction between normal and abnormal personality—the assertion that personality disorders are merely pathological distortions of normal personality attributes (Millon, 1990; Millon & Everly, 1985)—his theoretical system is particularly well suited for studying the implications of personality for political performance, because implicit in the principle of syndromal continuity is a built-in framework for risk analysis. In short, Millon’s system offers an integrated framework for construing normal variability and personality pathology, and suggests the likely nature and direction of personality decompensation under conditions of catastrophic personality breakdown.

Assessment Methodologies

Approaches to the indirect assessment of personality in politics can generally be classified into three categories: content analysis, expert ratings, and psychodiagnostic analysis of biographical data.

Content Analysis

The fundamental assumption of content-analytic techniques for at-a-distance (i.e., indirect) measures “is that it is possible to assess psychological characteristics of a leader by systematically analyzing what leaders say and how they say it” (Schafer, 2000, p. 512). Content analysis remains the dominant approach to indirect personality assessment and is widely acknowledged in political psychology as a reliable data-analytic method. It draws on the assumptions and methods of psychology, political science, and speech communication (Schafer, 2000, p. 512) and predates the establishment of political psychology as a discrete field—having been used, for example, to analyze Nazi propaganda during World War II. Holsti’s (1977) classic overview of qualitative and quantitative content-analytic approaches in political psychology remains relevant today, including his examination of perennial validity concerns such as the logic of psychological inferences about communicators engaging in persuasive communication (pp. 133–134); the ambiguities of authorship in documentary sources other than interviews and press conferences (p. 134); and problems of coding (e.g., word or symbol vs. theme or sentence coding) and data analysis (e.g., frequency vs. contingency measures; pp. 134–137). Paralleling advances in information technology, a recent development has been “automated content analysis” (Dille & Young, 2000), which “offers a less expensive, quicker, and more reliable alternative to commissioning graduate students to pore over and content-analyze texts” (p. 595).

Schafer (2000) and Walker (2000) provide good overviews of the current state of content-analytic at-a-distance assessment, its major conceptual and methodological issues, and future research directions. Clearly, content analysis can be a useful tool for dissecting political propaganda, examining psychologically relevant images in political rhetoric, and operationalizing important, politically relevant psychological constructs such as motives and conceptual or integrative complexity. However, content analysis does not offer a congenial frame of reference for comprehensive, clinically oriented psychological assessment procedures capable, in the words of Millon and Davis (2000), of capturing the patterning of personality variables “across the entire matrix of the person” (p. 65).

Expert Ratings

Paul Kowert (1996) has endeavored to move beyond the content-analytic methods (e.g., Hermann, 1980; Walker, 1990; Winter, 1987) that dominated political personality inquiry during the Cold War era, by applying Q-sort methodology to single-case analysis. In view of the huge role of public opinion polling, focus groups, professional speech writers, and political spin in contemporary politics, it seems prudent to find alternatives to speeches and interviews as primary sources of data for psychological evaluation.

An important advantage of expert ratings is that it yields coefficients of interrater reliability. However, this is offset by a variety of validity issues. Specifically, ratings by presidential scholars are fundamentally impressionistic and not based on systematic personality assessment (see Etheredge, 1978, p. 438). In some cases, high interrater reliability may merely reflect a convergence of conventional wisdom and shared myths about the personality characteristics of past presidents.

Amajor disadvantage of the expert-rating approach is that it is uneconomical, cumbersome, and impractical. To gather data for his study of the impact of personality on American presidential leadership, Kowert (1996) solicited 42 experts on American presidents. Rubenzer and his associates (2002), for their ambitious, highly resourceful study of U.S. presidents (employing primarily Big Five personality measures), attempted to contact nearly 1,000 biographers, presidential scholars, journalists, and former White House officials, eventually securing the cooperation of 115 raters who collectively completed 172 assessment packets, each containing 620 items.

A vexing difficulty with expert ratings is that it is impractical for studying candidates in the heat of presidential campaigns, when—as noted by Renshon (1996b)— accurate personality assessment is critical with respect to assessing psychological suitability for office. Historians and presidential scholars are not optimal sources of information under these conditions. Journalists who cover presidential candidates are potentially more reliable, but may be too immersed in their own reporting to offer much assistance.Amore practical approach would be to extract personality data directly from the writings of journalists, presidential scholars, biographers, and other experts, which obviates the need for soliciting their active cooperation.

Psychodiagnostic Analysis of Biographical Data

Simonton (1990) credits Lloyd Etheredge (1978) with establishing the diagnostic utility “of abstracting individual traits immediately from biographic data” to uncover the link between personality and political leadership (p. 677). Simonton (1986) argues that “biographical materials [not only] . . . supply a rich set of facts about childhood experiences and career development . . . [but] such secondary sources can offer the basis for personality assessments as well” (p. 150).

Etheredge (1978) used a hybrid psychodiagnostic/expertrating approach. As subjects he selected 36 U.S. presidents, secretaries of state, and presidential advisors who served between 1898 and 1968 and “assessed personality traits by searching scholarly works, insiders’ accounts, biographies, and autobiographies” of his subjects (p. 437). Specifically, Etheredge excerpted passages relevant to two dimensions: dominance–submission and introversion–extroversion. He deleted explicit information and cues regarding the identity of the political figures and then rated them on the two personality dimensions of interest, along with two independent judges who were unaware of the subjects’ identities.

Etheredge (1978), in commenting on “troublesome methodological issues” in such “second-hand assessment of historical figures,” raises an important problem with respect to atheoretical trait approaches to the study of personality:

A man like Secretary [JohnFoster]Dullescouldbedominantover his subordinates yet deferential to a superior. This social context must be standardized explicitly. I chose to assess dominance by assessing dominance over nominal subordinates on the assumption that a person’s inner desire to dominate would be less inhibited and show itself more clearly in this sector of life. In addition, since America’s use of force has often been directed against smaller countries, I felt this was the most relevant tendency of international behavior that would generalize. (p. 437)

Etheredge’s concerns highlight the indispensability of systematic import in personality-in-politics theorizing. Theorydriven conceptualization safeguards the psychodiagnostician against several pitfalls in Etheredge’s reasoning. Most important, in spuriously identifying a problem where none in fact existed, Etheredge introduced troubling confounds. The pattern that Etheredge observed with respect to Secretary Dulles transparently conveys a prototypical instance of the distinctive interpersonal conduct of highly conscientious (or compulsive) personalities. In stark contrast, highly dominant personalities consistently assert themselves in relation to both superiors and subordinates.

In lacking a prior personality taxonomy and proceeding atheoretically, Etheredge missed an important, politically relevant distinction with respect to dominance. Clearly, a purely dimensional scale can obscure important distinctions among disparate personality types. In short, dimensional prominence provides a necessary but insufficient basis for personality assessment; it must be complemented by categorical distinctiveness—in other words, a comprehensive theory of types.

This concern with categorical distinctiveness is reflected in the work of Lyons (1997), who used the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers & McCaulley, 1985) as a frame of reference for systematically extracting data from secondarysource biographies to construct a typological profile of U.S. president Bill Clinton, which he then used as a framework for analyzing President Clinton’s leadership style. However, in applying the Myers-Briggs model qualitatively, Lyons’s approach is somewhat impressionistic, lacking the empirical basis essential for assessing dimensional prominence and the nomothetic focus necessary for comparative study.

Anoteworthy aspect of Lyons’s method is that he used one set of biographies, predating Bill Clinton’s election as president, for extracting personality data and another set, focusing on the Clinton presidency, for inferring leadership style (see Lyons, 1997, p. 799). This is consistent with the solution implied in Greenstein’s (1992) critique that

single-case and typological studies alike make inferences about the inner quality of human beings…from outer manifestations— their past and present environments . . . and the pattern over time of their political responses. . . . They then use those inferred constructs to account for the same kind of phenomena from which they were inferred—responses in situational contexts.Thedanger of circularity is obvious, but tautology can be avoided by reconstructing personality from some response patterns and using the reconstruction to explain others. (pp. 120–121)

Greenstein’s point is valid insofar as it highlights the inherent danger of pseudoexplanations of leadership behaviors in terms of mere diagnostic labels. However, Lyons’s approach seems overly reductionistic and risks reifying the scientific method.At the operational level, it may be useful to view personality as the independent variable and leadership as the dependent variable—as if they were causally related. Conceptually, however, the relationship is fundamentally correlational. The fallacy involved in construing personality and leadership as hypothetical cause and effect, respectively, is akin to the so-called third-variable problem in correlational studies: Rather than manifest personality properties (x) causing observed leadership style (y), both variables likely express a common latent structure (z); to paraphrase Millon (1996), the “opaque or veiled inner traits” undergirding the “surface reality” (p. 4) of both observed variables.

Millon’s system offers abundant prospects for psychodiagnostic analysis of biographical data. Several personality inventories have been developed to assess personality from a Millonian perspective. Best known among these is the widely used Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–III (MCMI-III; Millon, Davis, & Millon, 1996), a standard clinical diagnostic tool employed worldwide. The Millon Index of Personality Styles (MIPS; Millon, 1994a) was developed to assess and classify personality in nonclinical (e.g., corporate) settings. Similarly, Strack (1991) developed the Personality Adjective Check List (PACL) for gauging normal personality styles. Oldham and Morris, in their trade book, The New Personality Self-Portrait (1995), offer a self-administered instrument congruent with Millon’s model. Immelman (1999; Immelman & Steinberg, 1999) adapted the Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria (MIDC) from Millon’s work, specifically for the assessment of personality in politics.

Immelman (1998, 2002) uses the MIDC to synthesize, transform, and systematize diagnostically relevant information collected from the literature on political figures (primarily biographical sources and media reports) into Millon’s (1990) four data levels (behavioral, phenomenological, intrapsychic, and biophysical). The next section outlines the Millonian approach to political personality assessment.

A Theory-Driven Psychodiagnostic Assessment Methodology

Favoring the more systematic, quantitative, nomothetic approach advocated by Simonton (1986, 1988, 1990), Immelman (1993, 1998, 2002) adapted Millon’s model of personality (1986, 1990, 1994a, 1996; Millon & Davis, 2000; Millon & Everly, 1985) for the indirect assessment of personality in politics. Immelman’s (1999) approach is equivalent to Simonton’s (1986, 1988) in that it quantifies, reduces, and organizes qualitative data extracted from the public record. It is dedicated to quantitative measurement, but unlike the currently popular five-factor model, which is atheoretical, the Millonian approach is theory driven. The assessment methodology yields a personality profile derived from clinical analysis of diagnostically relevant content in biographical materials and media reports, which provides an empirical basis for predicting the subject’s political performance and policy orientation (Immelman, 1998).

Sources of Data

Immelman (1998, 1999, 2002) gathers diagnostic information pertaining to the personal and public lives of political figures from a variety of published materials, selected with a view to securing broadly representative data sets. Pertinent selection criteria include comprehensiveness of scope (e.g., coverage of developmental history as well as political career), inclusiveness of literary genre (e.g., biography, autobiography, scholarly analysis, and media reports), and the writer’s perspective (e.g., a balance between admiring and critical accounts).

Personality Inventory

Greenstein (1992) criticizes analysts who “categorize their subjects without providing the detailed criteria and justifications for doing so” (p. 120). In Immelman’s (1999) approach, the diagnostic criteria are documented by means of a structured assessment instrument, the second edition of the MIDC (Immelman & Steinberg, 1999), which was compiled and adapted from Millon’s (1990, 1996; Millon & Everly, 1985) prototypal features and diagnostic criteria for normal personality styles and their pathological variants. The justification for classification decisions is provided by documentation from independent biographical sources. The Millon Inventory of Diagnostic Criteria Manual (Immelman, 1999) describes the construction, administration, scoring, and interpretation of the MIDC. The 12 MIDC scales (see Immelman, 1999, 2002, for the full MIDC taxonomy) correspond to major personality patterns posited by Millon (e.g., 1994a, 1996) and are coordinated with the normal personality styles described by Oldham and Morris (1995) and Strack (1997).

Diagnostic Procedure

The diagnostic procedure can be summarized as a three-part process: first, an analysis phase (data collection) in which source materials are reviewed and analyzed to extract and code diagnostically relevant psychobiographical content; second, a synthesis phase (scoring and interpretation) in which the unifying framework provided by the MIDC prototypal features, keyed for attribute domain and personality pattern, is employed to classify the diagnostically relevant information extracted in phase 1; and finally, an evaluation phase (inference) in which theoretically grounded descriptions, explanations, inferences, and predictions are extrapolated from Millon’s theory of personality, based on the personality profile constructed in phase 2 (Immelman, 1998, 1999, 2002).

Situational Variables, Experiential Filters, and Political Performance