View sample cognitive-experiential self-theory of personality research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Cognitive-experiential self-theory (CEST) is a broadly integrative theory of personality that is compatible with a variety of other theories, including psychodynamic theories, learning theories, phenomenological self-theories, and modern cognitive scientific views on information processing. CEST achieves its integrative power primarily through three assumptions. The first is that people process information by two independent, interactive conceptual systems, a preconscious experiential system and a conscious rational system. By introducing a new view of the unconscious in the form of an experiential system, CESTis able to explain almost everything that psychoanalysis can and much that it cannot, and it is able to do so in a scientifically much more defensible manner. The second assumption is that the experiential system is emotionally driven. This assumption permits CEST to integrate the passionate phallus-and-tooth unconscious of psychoanalysis with the “kinder, gentler” affect-free unconscious of cognitive science (Epstein, 1994). The third assumption is that four basic needs, each of which is assumed in other theories to be the one most fundamental need, are equally important according to CEST.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In this research paper, I review the basic assumptions of CEST, summarize the research conducted to test the theory, and note the implications of the theory for research and psychotherapy.

Two Information-Processing Systems

According to CEST, humans operate by two fundamental information-processing systems: a rational system and an experiential system. The two systems operate in parallel and are interactive. CEST has nothing new to say about the rational system, other than to emphasize the degree to which it is influenced by the experiential system. CEST does have a great deal to say about the experiential system. In effect, CEST introduces a new system of unconscious processing in the experiential system that is a substitute for the unconscious system in psychoanalysis. Although like psychoanalysis, CEST emphasizes the unconscious, it differs from psychoanalysis in its conception of how the unconscious operates. Before proceeding further, it should be noted that the word analytical principles and has no implications with respect to the reasonableness of the behavior, which is an alternative meaning of the word.

It is assumed in CEST that everyone, like it or not, automatically constructs an implicit theory of reality that includes a self-theory, a world-theory, and connecting propositions. An implicit theory of reality consists of a hierarchical organization of schemas. Toward the apex of the conceptual structure are highly general, abstract schemas, such as that the self is worthy, people are trustworthy, and the world is orderly and good. Because of their abstractness, generality, and their widespread connections with schematic networks throughout the system, these broad schemas are normally highly stable and not easily invalidated. However, should they be invalidated, the entire system would be destabilized. Evidence that this actually occurs is provided by the profound disorganization following unassimilable experiences in acute schizophrenic reactions (Epstein, 1979a). At the opposite end of the hierarchy are narrow, situation-specific schemas. Unlike the broad schemas, the narrower ones are readily susceptible to change, and their changes have little effect on the stability of the personality structure. Thus, the hierarchical structure of the implicit theory allows it to be stable at the center and flexible at the periphery. It is important to recognize that unlike other theories that propose specific implicit or heuristic rules of information processing, it is assumed in CEST that the experiential system is an organized, adaptive system, rather than simply a number of unrelated constructs or so-called cognitive shortcuts (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). As it is assumed in CEST that the experiential system in humans is the same system by which nonhuman animals adapt to their environments, it follows that nonhuman animals also have an organized model of the world that is capable of disorganization. Support for this assumption is provided by the widespread dysfunctional behavior that is exhibited in animals when they are exposed to emotionally significant unassimilable events (e.g., Pavlov, 1941).

Unlike nonhuman animals, humans have a conscious, explicit theory of reality in their rational system in addition to the model of reality in their experiential system. The two theories of reality coincide to different degrees, varying among individuals and situations.

Comparison of the Operating Principles of the Two Systems

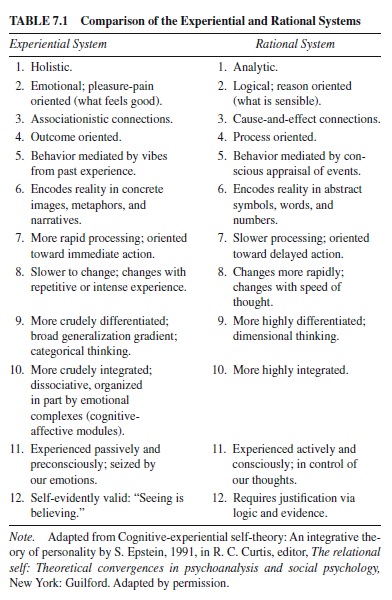

The experiential system in humans is the same system with which other higher order animals have adapted to their environments over millions of years of evolution. It adapts by learning from experience rather than by logical inference, which is the exclusive domain of the rational system. The experiential system operates in a manner that is preconscious, automatic, rapid, effortless, holistic, concrete, associative, primarily nonverbal, and minimally demanding of cognitive resources (see Table 7.1 for a more complete comparison of the two systems). It encodes information in two ways: as memories of individual events, particularly events that were experienced as highly emotionally arousing, and also in a more abstract, general way.

Although the experiential system is a cognitive system, its operation is intimately related to the experience of affect. It is, in fact, inconceivable that a conceptual system that learns from experience would not be used to facilitate positive affect and avoid negative affect. According to CEST, the experiential system both influences and is influenced by affect. Not only does the experiential system direct behavior in a manner anticipated to achieve pleasurable outcomes and to avoid unpleasurable ones, but the cognitions themselves are influenced by affect. As noted previously, the experiential conceptual system, according to CEST, is emotionally driven. After this is recognized, it follows that the affect-free unconscious proposed by cognitive scientists is untenable. The automatic, preconscious experiential conceptual system that regulates everyday behavior is of necessity an emotionally driven, dynamic unconscious system. Because affect determines what is attended to and what is reinforced, without affect there would be neither schemas nor motivation in the experiential system, and, therefore, no experiential system. It follows that CEST is as much an emotional as a cognitive theory.

In contrast to the experiential system, the rational system is an inferential system that operates according to a person’s understanding of the rules of reasoning and of evidence, which are mainly culturally transmitted. The rational system, unlike the experiential system, has a very brief evolutionary history. It operates in a manner that is conscious, analytical, effortful, relatively slow, affect-free, and highly demanding of cognitive resources (see Table 7.1).

Which system is superior? At first thought, it might seem that it must be the rational system. After all, the rational system, with its use of language, is a much more recent evolutionary development than is the experiential system, and it is unique to the human species. Moreover, it is capable of much higher levels of abstraction and complexity than is the experiential system, and it makes possible planning, longterm delay of gratification, complex generalization and discrimination, and comprehension of cause-and-effect relations. These attributes of the rational system have been the source of humankind’s remarkable scientific and technological achievements. Moreover, the rational system can understand the operation of the experiential system, whereas the reverse is not true.

On the other side of the coin, carefully consider the following question: If you could have only one system, which would you choose? Without question, the only reasonable choice is the experiential system. You could exist with an experiential system without a rational system, as the existence of nonhuman animals testifies, but you could not exist with only a rational system. Even mundane activities such as crossing a street would be excessively burdensome if you had to rely exclusively on conscious reasoning. Imagine having to estimate your walking speed relative to that of approaching vehicles so that you could determine when to cross a street. Moreover, without a system guided by affect, you might not even be able to decide whether you should cross the street. Given enough alternative activities to consider, you might remain lost in contemplation at the curb forever.

The experiential system also has other virtues, including the ability to solve some kinds of problems that the rational system cannot. For example, by reacting holistically, the experiential system can respond adaptively to real-life problems that are too complex to be analyzed into their components. Also, there are important lessons in living that can be learned directly from experience and that elude articulation and logical analysis. Moreover, as our research has demonstrated, the experiential system is more strongly associated with the ability to establish rewarding interpersonal relationships, with creativity, and with empathy than is the rational system (Norris & Epstein, 2000b). Most important is that the experiential system has demonstrated its adaptive value over millions of years of evolution, whereas the rational system has yet to prove itself and may yet be the source of the destruction of the human species as well as all other life on earth.

Fortunately, there is no need to choose between the systems. Each has its advantages and disadvantages, and the advantagesofonecanoffsetthelimitationsoftheother.Besides, we have no choice in the matter. We are they, and they are us. Where we do have a choice is in improving our ability to use each and to use them in a complementary manner.As much as we might wish to suppress the experiential system in order to be rational, it is no more possible to accomplish this than to stop breathing because the air is polluted. Rather than achieving control by denying the experiential system, we lose control when we attempt to do so: By being unaware of its operation, we are unable to take its influence into account. When we are in touch with the processing of the experiential system, we can consciously decide whether to heed or discount its influence. Moreover, if, in addition, we understand its operation, we can begin to take steps to improve it by providing it with corrective experiences.

How the Experiential System Operates

As noted, the operation of the experiential system is intimately associated with the experience of affect. For want of a better word, I shall use the word vibes to refer to vague feelings that may exist only dimly (if at all) in a person’s consciousness. Stating that vibes often operate outside of awareness is not meant to imply that people cannot become aware of them. Vibes are a subset of feelings, which include other feelings that are more easily articulated than vibes, such as those that accompany standard emotions. Examples of negative vibes arevaguefeelingsofagitation,irritation,tension,disquietude, queasiness, edginess, and apprehension. Examples of positive vibes are vague feelings of well-being, gratification, positive anticipation, calmness, and light-heartedness.

When a person responds to an emotionally significant event, the sequence of reactions is as follows: The experiential system automatically and instantaneously searches its memory banks for related events. The recalled memories and feelings influence the course of further processing and of behavioral tendencies. If the recalled feelings are positive, the person automatically thinks and has tendencies to act in ways anticipated to reproduce the feelings. If the recalled feelings are negative, the person automatically thinks and has tendencies to act in ways anticipated to avoid experiencing the feelings. As this sequence of events occurs instantaneously and automatically, people are normally unaware of its operation. Seeking to understand their behavior, they usually succeed in finding an acceptable explanation. Insofar as they can manage it without too seriously violating reality considerations, they will also find the most emotionally satisfying explanation possible.This process of finding an explanation in the rational system for what was determined primarily by the experiential system and doing so in a manner that is emotionally acceptable corresponds to what is normally referred to as rationalization. According to CEST, such rationalization is a routine process that occurs far more often than is generally recognized. Accordingly, the influences of the experiential system on the rational system and its subsequent rationalization are regarded, in CEST, as major sources of human irrationality.

The Four Basic Needs

Almost all of the major theories of personality propose a single, most basic need. CEST considers the four most often proposed needs as equally basic. It is further assumed in CEST that their interaction plays an important role in behavior and can account for paradoxical reactions that have eluded explanation by other theoretical formulations.

Identification of the Four Basic Needs

In classical Freudian theory, before the introduction of the death instinct, the one most basic need was the pleasure principle, which refers to the desire to maximize pleasure and minimize pain (Freud, 1900/1953). Most learning theorists make a similar implicit assumption in their view of what constitutes reinforcement (e.g., Dollard & Miller, 1950). For other theorists, such as object-relations theorists, most notably Bowlby (1988), the most fundamental need is the need for relatedness. For Rogers (1951) and other phenomenological psychologists, it is the need to maintain the stability and coherence of a person’s conceptual system. For Allport (1961) and Kohut (1971), it is the need to enhance self-esteem. (For a more thorough discussion of these views, see Epstein, 1993.) Which of these views is correct? From the perspective of CEST, they are all correct, because each of the needsis basic—but they are also all incorrect because of their failure to recognize that the other needs are equally fundamental. They are equally fundamental in the sense that each can dominate the others. Moreover, there are equally serious consequences, including disorganization of the entire personality structure, when any one of the needs is insufficiently fulfilled.

Interactions Among the Basic Needs

Given four equally important needs that can operate simultaneously, it follows that behavior is determined by the combined influence of those needs that are activated in a particular situation. An important adaptive consequence of such influence is that the needs serve as checks and balances against each other. When any need is fulfilled at the expense of the others, the intensity of the others increases, thereby increasing the motivation to satisfy the other needs. However, under certain circumstances the frustration of a need may be so great that frustration of the other needs is disregarded, which can have serious maladaptive consequences. As is shown next, these assumptions about the interaction of basic needs can resolve some important, otherwise paradoxical findings.

The finding that normal people characteristically have unrealistic self-enhancing and optimistic biases (Taylor & Brown, 1988) has evoked considerable interest because it appears to contradict the widely held assumption that reality awareness is an important criterion of mental health. From the perspective of CEST, this finding does not indicate that reality awareness is a false criterion of mental health, but only that it is not the only criterion. According to CEST, a compromise occurs between the need to realistically assimilate the data of reality into a stable, coherent conceptual system and the need to enhance self-esteem. The result is a modest self-enhancing bias that is not unduly unrealistic. It suggests that normal individuals tend to give themselves the benefit of the doubt in situations in which the cost of slight inaccuracy is outweighed by the gain in positive feelings about the self. Note that this assumes that the basic need for a favorable pleasure-pain balance is also involved in the compromise.

There are more and less effective ways of balancing basic needs. A balance that is achieved among equally unfulfilled competing needs is a prescription for chronic distress—not good adjustment. Whereas poorly adjusted people tend to fulfill their basic needs in a conflictual manner, well-adjusted people fulfill their basic needs in a synergistic manner, in which the fulfillment of one need contributes to rather than conflicts with the fulfillment of the other needs. They thereby maintain a stable conceptual system, a favorable pleasurepain balance, rewarding interpersonal relationships, and a high level of self-esteem.

Let us first consider an example of a person who balances her basic needs in a synergistic manner and then consider an opposite example. Mary is an emotionally stable, happy person with high self-esteem who establishes warm, rewarding relationships with others. She derives pleasure from helping others. This contributes to her self-esteem, as she is proud of her helpful behavior and others admire and appreciate her for it. As a result, Mary’s behavior also contributes to favorable relationships with others. Thus, Mary satisfies all her basic needs in a harmonious manner.

Now, consider a person who fulfills his basic needs in a conflictual manner. Ralph is an unhappy, unstable person with low self-esteem who establishes poor relationships with others. Because of his low self-esteem, Ralph derives pleasure from defeating others and behaving in other ways that make him feel momentarily superior. Not surprisingly, this alienates people, so he has no close friends. Because of his low self-esteem and poor relationships with others, he anticipates rejection, from which he protects himself by maintaining a distance from people. His low self-esteem and poor relationships with others contribute to feelings of being unworthy of love as well as to an unfavorable pleasure-pain balance. Because his conceptual system is failing to fulfill its function of directing his behavior in a manner that fulfills his basic needs, it is under the stress of potential disorganization, which he experiences in the form of anxiety. The more his need for enhancing his self-esteem is thwarted, the more he acts in a self-aggrandizing manner, which exacerbates his problems with respect to fulfilling his other basic needs.

Imbalances in the Basic Needs as Related to Specific Psychopathologies

Specific imbalances among the basic needs are associated with specific mental disorders. For present purposes, it will suffice to present some of the more obvious examples.

Paranoia with delusions of grandeur can be understood as a compensatory reaction to threats to self-esteem. In a desperate attempt to buoy up self-esteem, paranoid individuals disregard their other needs. They sacrifice their need to maintain a favorable pleasure-pain balance because their desperate need to maintain their elevated self-esteem is continuously threatened. They sacrifice their need to maintain relationships because their grandiose behavior alienates others who do not appreciate being treated as inferiors and who are repelled by their unrealistic views. The situation is somewhat more complicated with respect to their need to realistically assimilate the data of reality into a coherent, stable, conceptual system. They sacrifice the reality aspect of this need but not the coherence aspect. In both of these respects they are similar to paranoid individuals with delusions of persecution, considered in the next example.

Paranoia with delusions of persecution can be understood as a desperate attempt to defend thestability of a person’s conceptual system and, to a lesser extent, to enhance self-esteem.

By viewing their problems in living as resulting from persecution by others, paranoid people with delusions of persecution can focus all their attention and resources on defending themselves. Such focus and mobilization provide a highly unifying statethatserveasaneffectivedefenseagainstdisorganization. Delusions of persecution also contribute to self-esteem because the perception of the persecutors as powerful or prestigious, which is invariably the case, implies that the target of the persecution must also be important. The basic needs that are sacrificed are the pleasure principle, as being persecuted is a terrifying experience, and the need for relatedness, as others are either viewed as enemies or repelled by the unrealistic behavior.

Schizophrenic disorganization can be understood as the best bargain available for preventing extreme misery under desperate circumstances in which fulfillment of the basic needs is seriously threatened. Ultimate disorganization is a state devoid of conceptualization and (relatedly) therefore of feelings. Although its anticipation is dreaded, its occurrence corresponds to a state of nonbeing, a void in which there are neither pleasant nor unpleasant feelings (Jefferson, 1974). Thus, what is gained is a net improvement in the pleasurepain balance (from a negative to a zero value). What is sacrificed are the needs to maintain the stability of the conceptual system, to maintain relatedness, and to enhance self-esteem.

The Four Basic Beliefs

The four basic needs give rise to four corresponding basic beliefs, which are among the most central constructs in a personal theory of reality. They therefore play a very important role in determining how people think, feel, and behave in the world. Moreover, as previously noted, because of their dominant and central position and their influence on an entire network of lower-order beliefs, should any of them be invalidated, the entire conceptual system would be destabilized. Anticipation of such disorganization would be accompanied by overwhelming anxiety. The disorganization, should it occur (as previously noted) would correspond to an acute schizophrenic reaction.

The question may be raised as to how the four basic needs give rise to the development of four basic beliefs. Needs, or motives, in the experiential system, unlike those in the rational systems, always include an affective component. They therefore determine what is important to a person at the experiential level and what a person is spontaneously motivated to pursue or avoid. Positive affect is experienced whenever a need is fulfilled, and negative affect is experienced whenever the fulfillment of a need is frustrated. Because people wish to experience positive affect and to avoid negative affect, they automatically attend to whatever is associated with the fulfillment or frustration of a basic need. As a result, they develop implicit beliefs associated with each of the basic needs. Let us examine this idea in greater detail.

Depending on a person’s history in fulfilling the need to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, a person tends to develop a basic belief about the world along a dimension varying from benign to malevolent. Thus, if a person experienced an environment that was predominantly a source of pleasure and security, the person will most likely develop the basic belief that the world is a good place in which to live. If a person has the opposite experiences, the person will tend to develop the opposite basic belief. The basic belief about the benignity versus malevolence of the world is the core of a network of related beliefs, including optimistic versus pessimistic views about future events.

Corresponding to the basic need to represent the data of reality in a stable and coherent conceptual system is a basic belief about the world that varies along a dimension of meaningful versus meaningless. Included in the network of related beliefs are beliefs about the predictability, controllability, and justness of the world versus its unpredictability, uncontrollability, and lack of justice. Corresponding to the basic need for relatedness is a basic belief about people that varies along a dimension from helpful and trustworthy to dangerous and untrustworthy. Included in the network of related beliefs are beliefs about the degree to which people are loving versus rejecting and trustworthy versus untrustworthy. Corresponding to the basic need for self-enhancement is a basic belief about the self that varies along a dimension from worthy to unworthy. Included in the network of related beliefs are beliefs about how competent, moral, worthy of love, and strong the self is compared to how incompetent, immoral, unworthy of love, and weak it is.

Interaction of the Experiential and Rational Systems

As previously noted, according to CEST, the experiential and rational systems operate in parallel and are interactive.

The Influence of the Experiential System on the Rational System

As the experiential system is the more rapidly reacting system, it is able to bias subsequent processing in the rational system. Because it operates automatically and preconsciously, its influence normally occurs outside of awareness. As noted previously, this prompts people to search for an explanation in their conscious rational system, which often results in rationalization. Thus, even when people believe their thinking is completely rational, it is often biased by their experiential processing.

The biases that influence conscious, rational thinking in everyday life are, for the most part, adaptive, as the experiential system operates according to schemas learned from past experience. In some situations, however, the experientially determined biases and their subsequent rationalizations are highly maladaptive. An extreme case is the life-long pursuit of “false goals.” Such goals are false in the sense that their achievement is followed by disappointment and sadness, rather than by the anticipated happiness, enhanced selfesteem, or security that was the reason for their pursuit. It is noteworthy that the achievement of a false goal is experientially disappointing although at the rational level, it is viewed as a significant achievement about which the individual is proud.ThefollowingpassagefromTolstoi(1887),inwhichhe describes his thoughts during a period of depression, provides a poignant example of such a reaction:

When I thought of the fame which my works had gained me, I used to say to myself, ‘Well, what if I should be more famous than Gogol, Pushkin, Shakespeare, Moliere—than all the writers of the world—well, and what then? I could find no reply. Such questions demand an answer, and an immediate one; without one it is impossible to live, but answer there was none.

My life had come to a sudden stop. I was able to breathe, to eat, to drink, to sleep. I could not, indeed, help doing so; but there was no real life in me. I had not a single wish to strive for the fulfillment of what I could feel to be reasonable. If I wished for something, I knew beforehand, that were I to satisfy the wish, nothing would come of it, I should still be dissatisfied.

Such was the condition I had come to, at the time when all the circumstances of my life were preeminently happy ones, and when I had not yet reached my fiftieth year. I had a good, a loving, and a well-beloved wife, good children, a fine estate, which, without much trouble on my part, continually increased my income; I was more than ever respected by my friends and acquaintances; I was praised by strangers, and could lay claim to having made my name famous . . .

The mental state in which I then was seemed to me summed up into the following: my life was a foolish and wicked joke played on me by I knew not whom . . .

Had I simply come to know that life has no meaning, I could have quietly accepted it as my allotted position. I could not, however, remain thus unmoved. Had I been like a man in a wood, about which he knows that there is no issue, I could have lived on; but I was like a man lost in a wood, and, who, terrified by the thought, rushes about trying to find a way out, and though he knows each step can only lead him farther astray, can not help running backwards and forwards.

Two features of Tolstoi’s situation are of particular interest. One is that he experiences deep despair after achieving his life goals. This suggests that his achievements, although viewed as successes in his rational system, failed to fulfill a basic need or needs in his experiential system. His success, therefore, can be said to be success at the rational level but failure at the experiential level. This raises the question of what the deeply frustrated need in his experiential system might be. In the absence of additional information, it is, of course, impossible to know, and one can only speculate. One possibility within the framework of CEST is that the frustrated need was for unconditional love in early childhood. Such a need, of course, cannot be satisfied by material rewards or accomplishments.

The other interesting observation is that Tolstoi is distressed not only because of his feelings of emptiness and meaninglessness, but that, try as he might, he cannot solve the problem of why he should be unhappy when all the conditions of his life suggest that he should be happy. It follows from CEST that the reason he cannot solve his problem, despite his considerable intelligence and motivation, is that he believes it exists in his rational system when in fact it exists in his experiential system. Moreover, assuming the speculation about frustration of unconditional love in childhood is true, its early, preverbal occurrence and its remoteness from the kinds of motives normally present in the rational systems of adults can help account for Tolstoi’s inability to articulate the source of his distress.

The influence of the experiential system on the rational system can be positive as well as negative.As an associative system, the experiential system can be a source of creativity by suggesting ideas that would not otherwise be available to the linear-processing rational system. Because the experiential system is a learning system, it can be a source of useful information, which can be incorporated into the rational system. Most important is that the experiential system can provide a source of passion for the rational system that it would otherwise lack. The result is that intellectual pursuits can be pursued with heart, rather than as dispassionate intellectual exercises.

The Influence of the Rational System on the Experiential System

As the slower system, the rational system is in a position to correct the experiential system. It is common for people to reflect on their spontaneous, impulsive thoughts, recognize they are inappropriate, and then substitute more constructive ones. For example, in a flash of anger an employee may have the thought that he would like to tell off his boss, but on further reflection may decide this course of action would be most unwise.To investigate this process, we conducted an experiment in which people were asked to list the first three thoughts that came to mind in response to reading a variety of provocative situations. The first thought was often counterproductive and in the mode of the experiential system, whereas the third thought was usually corrective and in the mode of the rational system.

The rational system can also influence the experiential system by providing the understanding that allows a person to train the experiential system so that its initial reactions are more appropriate. That is, by understanding the operating principles of the experiential system as well as its schemas, it is possible to determine how that system can be improved; this can be accomplished in a variety of ways, the most obvious of which is by disputing the maladaptive thoughts in the experiential system, a procedure widely utilized by cognitive therapists. As the experiential system learns directly from experience, another procedure is to provide real-life corrective experiences. A third procedure is to utilize imagery, fantasy, and narratives for providing corrective experiences vicariously.

The rational system can influence the experiential system in automatic, unintentional ways as well as by its intentional employment. As the experiential system operates in an associative manner, thoughts in the rational system can trigger associations and thereby emotions in the experiential system. For example, a student attempting to solve a mathematics word problem may react to the content with conscious thoughts that produce associations in the experiential system; the associations then elicit emotional reactions that interfere with performance. In this illustration, we have an interesting cycle of the rational system’s influencing the experiential system, which in turn influences the rational system.

Another unintentional way in which the rational system can influence the experiential system is through repetition of thoughts or behavior in the rational system.Through such repetition, thoughts and behavior that were originally under rational control can become habitualized or proceduralized, with the control shifting from the rational to the experiential system (Smith & DeCoster, 2000). An obvious advantage to this shift in control is that the thought and behavior require fewer cognitive resources and can occur without conscious awareness. Potential disadvantages are that the habitual thoughts and behavior are under reduced volitional control and are more difficult to change. Although this can be desirable for certain constructive thoughts and behaviors, it is problematic when the thoughts and behavior are counterproductive.

The Lower and Higher Reaches of the Experiential System

The experiential system operates at different levels of complexity. Classical conditioning is an example of the operation of the experiential system at its simplest level. In classical conditioning,aconditioned,neutralstimulus(theCS),suchas a tone, precedes an unconditioned stimulus (the UCS), such as food. Over several trials, a connection is formed between the conditioned and unconditioned stimulus, so that the conditioned stimulus evokes a conditioned response (the CR), such as salivation, that originally occurred only to the UCS. This process illustrates the operation of several of the attributes of the experiential system, including associative processing, automatic processing, increased strength of learning over trials, affective influence (e.g., emotional significance of the UCS), and arbitrary outcome-orientation (e.g., reacting to the CS independent of its causal relation to the UCS). The CS is also responded to holistically, as the animal reacts not only to the tone, but to the entire laboratory context.

Amore complex operating level of the experiential system is exhibited in heuristic processing. In an article that has had a widespread influence on understanding decisional processes, Tversky and Kahneman (1974) introduced the concept of heuristics, which they defined as cognitive shortcuts that people use naturally in making decisions in conditions of uncertainty. They and other cognitive psychologists have found such processing to be a prevalent source of irrational reactions in a wide variety of situations. For example, people typically report that the protagonists in specially constructed vignettes would become more upset following arbitrary outcomes preceded by acts of commission than by acts of omission, by near than by far misses, by free than by constrained behavior, and by unusual than by usual acts. As they respond as if the protagonist’s behavior were responsible for the arbitrary outcomes, their thinking is heuristic in the sense that it is based on simple associative reasoning rather than on cause-andeffect analysis.

A vast amount of research on heuristic processing (see review in Fiske & Taylor, 1991) has produced results that are highly consistent with the principles of experiential processing. Although the data-driven views on heuristic processing derived from social-cognitive research and the theory-driven views of CEST have much in common, the two approaches differ in three important respects. One is that CEST attributes heuristics to the normal mode of operation of an organized conceptual system, the experiential system, that is contrasted with an alternative organized conceptual system, the rational system. The second is that heuristic processing and the experiential system in CEST are embedded in a global theory of personality. The third is that heuristic processing, according to CEST, has withstood the test of time over millions of years of evolution, and is considered to be primarily adaptive. In contrast to these views, social cognitive psychologists, such as Kahneman and Tversky (1973) and Nisbett and Ross (1980), regard heuristics as individual “cognitive tools” that are employed within a single conceptual system that includes both associative (experiential) and analytical (rational) reasoning. These theorists further regard heuristics as quirks in thinking that although sometimes advantageous are common sources of error in everyday life, and therefore are usually desirable to eliminate. It is of interest in this respect to note how resistant some of these blatantly nonrational ways of processing have been to elimination by training. From the perspective of CEST, given the intrinsically compelling nature of experiential processing and its highly adaptive value in most situations in everyday life, such resilience is to be expected.

Although the experiential system encodes events concretely and holistically, it is nevertheless able to generalize, integrate, and direct behavior in complex ways, some of which very likely involve a contribution by the rational system. It does this through prototypical, metaphorical, symbolic, and narrative representations in conjunction with the use of analogy and metaphor. Representations in the experiential system are also related and generalized through their associations with emotions. It is perhaps through processes such as these that the experiential system is able to make its contributions to empathy, creativity, the establishment of rewarding interpersonal relationships, and the appreciation of art and humor (Norris & Epstein, 2000b).

Psychodynamics

Psychodynamics, as the term is used here, refers to the interactions of implicit motives and of implicit beliefs and their influence on conscious thought and behavior. The influence on conscious thought and behavior is assumed to be mediated primarily by vibes. Two major sources of vibes that are important sources of maladaptive behavior are early-acquired beliefs and needs.

The Influence of Early-Acquired Beliefs on Maladaptive Behavior

As you will recall, according to CEST, the implicit beliefs in a person’s experiential system consist primarily of generalizations from emotionally significant past experiences. These affect-laden implicit beliefs correspond to schemas about what the self and other people are like and how one should relate to them. Particularly important sources of such schemas are experiences with mother and father figures and with siblings. The schemas exist in varying degrees of generality. At the broadest level is the basic belief about what people in general are like, as previously discussed.At a more specific level are views about particular categories of people, such as authority figures, maternal figures, mentors, and peers. Such implicit beliefs, both broader and narrower ones, exert astrong influence on how people relate to others, particularly to those who provide cues that are reminders of the original generalization figures. The influence of the schemas is mediated by the vibes automatically activated in cue-relevant situations.

It is understandable why implicit beliefs that contribute to a person’s happiness and security are maintained. But why should implicit beliefs that appear to contribute only to misery also be maintained? Why do they not extinguish as a result of the negative affect following their retrieval? According to the pleasure principle, they should, of course. They do not because of the influence of the need to maintain the stability of one’s conceptual system (Epstein & Morling, 1995; Hixon & Swann, 1993; Morling & Epstein, 1997; Swann, 1990). Depending on circumstances, the need for stability can override the pleasure principle. But how exactly does this operate? What do people actually do that prevents their maladaptive beliefs acquired in an earlier period from being extinguished when they are exposed to corrective experiences in adulthood?

There are three things people do or fail to do that serve to maintain their maladaptive implicit beliefs. First, they tend to perceive and interpret events in a manner that is consistent with their biasing beliefs. Biased perceptions and interpretations allow individuals to experience events as verifying a belief even when on an objective basis they should be disconfirming it. For example, an offer to help or an expression of concern can be perceived as an attempt to control one, and an expression of love can be viewed as manipulative. Second, people often engage in self-verifying behavior, such as by provoking counterbehavior in others that provides objective confirmation of the initial beliefs. For example, a person who fears rejection in intimate relationships may behave with aggression or withdrawal whenever threatened by relationships advancing toward intimacy. This predictably provokes the other person to react with counteraggression or withdrawal, thereby providing objective evidence confirming the belief that people are rejecting. Third, people fail to recognize the influence of their implicit beliefs and associated vibes on their behavior and conscious thoughts, which prevents them from identifying and correcting their biased interpretations and self-verifying behavior. As a result, they attribute the consequences of their maladaptive behavior to unfavorable circumstances or, more likely, to the behavior of others. In the event that after repeated failed relationships, they should consider the possibility that their own behavior may play a role, they are at a loss to understand in what way this could be true, as they can cite objective evidence to support their biased views. You will recall that an important maxim in CEST is that a failure to recognize the operation of one’s experiential system means that one will be controlled by it.

There is an obvious similarity between the psychoanalytic concept of transference and the view in CEST that people’s relationships are strongly influenced by generalizations from early childhood experiences with significant others. Psychoanalysts have long emphasized the importance of transference relations in psychotherapy. They have observed that their patients, after a period in therapy, react to the analyst as if the analyst were a mother or a father figure. They encourage the development of such transference reactions with the aim of providing a corrective emotional experience. Through the use of this procedure as well as by interpreting the transference, the analyst hopes to eliminate the tendency of the patient to establish similar relationships with others. Although this procedure is understandable from the perspective of CEST, it is fraught with danger, as the patient may become overly dependent on the therapist and the therapist, despite the best of intentions, may provide a destructive rather than a corrective experience. Moreover, working through a transference relationship—even when successful—may not be the most efficient way of treating inappropriate generalizations. Nevertheless, for present purposes, it illustrates how generalizations from early childhood tend to be reproduced in later relationships, including those with therapists, and how appropriate emotional experiences can correct maladaptive generalizations.

Although there are obvious similarities between the concepts of transference in psychoanalysis and of generalization in CEST, there are also important differences. Generalization is a far broader concept, which, unlike transference, is not restricted to the influence of relationships with parents. Rather, it refers to the influence of all significant childhood relationships, including in particular those with siblings as well as with parents. Schemas derived from childhood experiences are emphasized in CEST because later experiences are assimilated by earlier schemas. Also, generalizations acquired from childhood experiences are likely to be poorly articulated (if articulated at all) in the rational system. Their influence, therefore, is likely to continue to be unrecognized into adulthood.

The Influence of Early-Acquired Motives on Maladaptive Behavior

Much of what has been said about implicit beliefs in the experiential system can also be applied to implicit needs. Like implicit beliefs, implicit needs or motives are acquired from emotionally significant experiences. They are also maintained for similar reasons. As previously noted, when people experience a positive or negative event, they automatically acquire a behavioral tendency or motive to reproduce the experience if it was favorable and to avoid experiencing it if it was unfavorable. The stronger the emotional response and the more often it occurs in the same or similar situations, the greater the strength of the motive. Although this learning procedure is adaptive most of the time, it is maladaptive when past conditions are unrepresentative of present ones. One such condition is when a child has experiences involving the deep thwarting of one or more basic needs. For example, if the need to maintain self-esteem is deeply frustrated in childhood, the child will acquire a sensitivity to threats to selfesteem and a corresponding compulsion to protect himself or herself from such threats in the future. Sensitivities, in CEST, refer to areas of particular vulnerability, and compulsions refer to rigid, driven behavioral tendencies with the aim of protecting oneself from sensitivities. Such sensitivities and compulsions are considered in CEST to be major sources of maladaptive behavior.

The following case history illustrates the operation of a sensitivity and compulsion. In this and other case histories, names, places, and details are altered to protect the anonymity of the protagonists. Ralph was the oldest child in a family that included three other children. He was extremely bright and far outshone his siblings in academic performance. However, rather than being appreciated for it, he was resented by both his parents and siblings. When he eagerly showed his mother the excellent grades on his report card, she would politely tell him that she was busy at the moment and would like to look at it later, when she had more time. Not infrequently, she would forget to do so. It gradually became evident to Ralph that she was more upset than pleased with his accomplishments, so he stopped informing her about them.

The mother’s behavior can be understood in terms of her own background. She had been deeply resentful, as a child, when her mother expressed admiration for the accomplishments of her brighter sibling and ignored her own accomplishments. Thus, her automatic reaction to cues that reminded her of such experiences was to have unpleasant vibes accompanied by resentful thoughts. Consequently, although she meant to be a good mother to Ralph, her experiential reactions undermined her conscious intent. Being unaware of her underlying experiential reactions, she could not help but react as she did. Moreover, over time she found objective reasons for considering him as her least favored child. Little did she realize that his resentful and reticent attitude toward her and others were reactions to her own behavior toward him. She simply regarded him as a stubborn, difficult child by nature.

As a result of his experience in the family, Ralph developed feelings of being unlovable and unworthy and felt depressed much of the time. As an adult, he devoted his energy to bolstering his self-esteem by working extremely hard at becoming a successful businessman. He succeeded at this to a remarkable extent, becoming wealthy at an early age. Yet despite his success and accumulation of material things that other people admired, happiness eluded him. He continued to feel unlovable and depressed no matter what his possessions were and no matter that he had a wife and children who tried hard to please him. When his wife praised the children for their accomplishments, he became resentful toward her and the children. He spent less and less time with his family and increasingly immersed himself in his business. He also began to accuse his wife and children of not loving him and said that was the reason he was spending so little time with them. In his eyes, he was the victim of rejection, not its perpetrator. The result was that he increasingly alienated his family, which verified for him that they did not love him. He became convinced that his wife would ask him for a divorce, and rather than be openly rejected by her, he asked her for a divorce first. He was sure she would be pleased to oblige, and he was extremely relieved when she protested that she did not want a divorce. She said that she wanted more than anything else for them to work together to improve their relationship. This gave a great boost to Ralph, and he tried to the best of his ability to be a more attentive husband and father. This was no easy task for him, particularly as he had no insight into the role his own behavior played in his distressing relationships with his family. It remains to be seen if he will succeed. From the perspective of CEST, it is doubtful that he will unless he gains insight into the influence of his experiential system.

This case illustrates the development, operation, and consequences of a sensitivity and compulsion. Of further interest is that it illustrates the transference of sensitivities and compulsions across generations. The mother’s sensitivity was to being outshone intellectually, and her compulsion was to get back in some way or other at whomever activated the sensitivity. In this case it was her own son, who provided cues reminiscent of her childhood experiences with her brighter sibling. Lest you blame the mother, consider that her reactions occurred automatically, outside of her awareness, and that she was no less a victim than was Ralph.

Ralph had three related sensitivities: threat to his selfesteem, lack of appreciation for his accomplishments, and rejection by a loved one. His compulsive reaction in response to the first sensitivity was to attempt to increase his selfesteem by becoming an outstanding success in business and thereby gaining the admiration of others. His compulsive reaction to the second sensitivity was again to gain the admiration of others for his success and material possessions. His compulsive reaction to the third sensitivity was to withdraw from and reject the members of his family before they rejected him. Not surprisingly, his compulsive reactions interfered with rather than facilitated gaining the love he so desperately desired.

Research Support for the Construct Validity of Cest

Research generated by a variety of dual-process theories other than CEST has produced many findings consistent with the assumptions in CEST (see review in Epstein, 1994, and articles in Chaiken & Trope, 1999).As a review of this extensive literature is beyond the scope of this research paper, here I confine the discussion to studies my associates and I specifically designed to test assumptions in CEST. Three kinds of research are reviewed: research on the operating principles of the experiential system, research on the interactions within and between the two systems, and research on individual differences in the extent and efficacy in the use of the two systems.

Research on the Operating Principles of the Experiential System

For some time, my associates and I have been engaged in a research program for testing the operating principles of the experiential system. One of our approaches consisted of adapting procedures used by Tversky and Kahneman and other cognitive and social-cognitive psychologists to study heuristic, nonanalytical thinking through the use of specially constructed vignettes (for examples of this research by others, see Fiske & Taylor, 1991; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974, 1983; Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982).

Irrational Reactions to Unfavorable Arbitrary Outcomes

People in everyday life often react to arbitrary, unintended outcomes as if they were intentionally and causally determined. Thus, they view more favorably the proverbial bearer of good than of evil tidings despite knowing full well that the messenger is not responsible for the message. Such behavior is an example of outcome-oriented processing. It is the typical way the experiential system reacts to events—by associating outcomes with the stimuli that precede the outcomes, as in classical conditioning.

As an example of the kinds of vignettes we used, one of them described a situation in which two people, as the resultof unanticipated heavy traffic, arrive at an airport 30 minutes after the scheduled departure of their flights. One learns that her flight left on time, and the other learns that her flight just left. Tversky and Kahneman (1983) found that people typically reported that the one who barely missed her flight would be more upset than the other protagonist would be, although from a rational perspective it should not matter at all as both were equally inconvenienced and neither was responsible for the outcome. We modified Tversky and Kahneman’s experiment by having the participants respond from three perspectives: how they believed most people would react; how they themselves would react based on how they have reacted to similar situations in the past, and how a completely logical person would react (Epstein, Lipson, Holstein, & Huh, 1992). The first two perspectives were considered to be mainly under the jurisdiction of the experiential system and the third to be mainly under the jurisdiction of the rational system. In order to control for and examine the influence of each of the perspectives on the effect of subsequent perspectives, we counterbalanced the order of presentation of the perspectives.

The findings supported the following hypotheses: There are two different modes of information processing, experiential and rational; the experiential system is an associative system that automatically relates outcomes to preceding situations and behavior, treating them as if they are causally related, even when the relation is completely arbitrary; the rational system is an analytical system that judges cause-andeffect relations according to logical rules; and the systems are interactive, with each influencing the other. Support for the last hypothesis is of particular interest, as it supports the important assumption in CEST that the prevalence of irrational thinking in humans can be attributed largely to the influence of their automatic, preconscious experiential processing on their conscious analytical thinking.

In research on arbitrary outcomes in which we varied the affective consequences of the outcomes, the results supported theassumptioninCESTthatthedegreeofexperientialrelative to rational influence varies directly with the intensity of the affect that is implicated (Epstein et al., 1992). What we found is that the greater the emotional intensity of the outcomes, the more the responses reflected experiential (vs. rational) processing.

The Ratio-Bias Phenomenon

Imagine that you are told that on every trial in which you blindly draw a red jellybean from a bowl containing red and white jellybeans, you will receive two dollars. To make matters more interesting, you are given a choice between drawing from either of two bowls that offer the same 10% odds of drawing a winning bean. One contains one red jellybean and nine white ones; the other contains 10 red jellybeans and 90 white ones. Which bowl would you choose to draw from, and how much would you pay for the privilege of drawing from the bowl of your choice, rather than having the choice decided by the toss of a coin? When people are simply asked how they would behave, almost all say they would have no preference and would not pay a cent for a choice between two equal probabilities. Yet when they are placed in a real situation, most willingly pay small sums of money for the privilege of drawing from the bowl with more red jellybeans (Kirkpatrick & Epstein, 1992). This difference in response to the verbally presented and the real situation can be explained by the greater influence of the experiential than the rational system in real situations with emotionally significant consequences compared to simulated situations without consequences. According to CEST, the experiential system is particularly reactive to real experience, whereas the rational system is uniquely responsive to abstract, verbal representations.

This jellybean experimental situation, otherwise referred to as the ratio-bias experimental paradigm, is particularly interesting with respect to CEST because it pits experiential against rational processing. The conflict between the two modes of processing arises because the experiential system is a concrete system that is less responsive to abstractions such as ratios than to the numerousness of objects. Comprehension of numerousness, unlike comprehension of ratios, is an extremely fundamental ability that is within the capacity of 3-year-old children and nonhuman animals (Gallistel & Gelman, 1992).

Even more impressive than the irrational behavior exhibited by people paying for the privilege of choosing between bowls that offer equal probabilities are the results obtained when unequal probabilities are offered by the bowls. If our reasoning is correct, a conflict between the two systems can be established by having one bowl probability-advantaged and the other numerousness-advantaged. In one study, the probability-advantaged bowl always contained 1 in 10 red jellybeans, whereas the numerousness-advantaged bowl offered between 5 and 9 red jellybeans out of 100 jellybeans, depending on the trial (Denes-Raj & Epstein, 1994). Under these circumstances, many adults made nonoptimal responses by selecting the numerousness-advantaged bowl against the better judgment of their rational thinking. For example, they often chose to draw from the bowl that contained 8 of 100 (8%) in preference to the one that contained 1 of 10 (10%) red jellybeans. Some sheepishly commented that they knew it was foolish to go against the probabilities, but somehow they felt they had a better chance of drawing a red jellybean when there were more of them. Of additional interest, participants made nonoptimal responses only to a limited degree, thereby suggesting a compromise between the two systems. Thus, although many selected a numerousnessadvantaged 8% option (8 of 100 red jellybeans) over a 10% probability-advantaged one (1 of 10 red jellybeans), almost no one selected a 5% numerousness-advantaged option (5 of 100 red jellybeans) over a 10% probability-advantaged option (1 of 10 red jellybeans). Apparently, most people preferred to behave according to their experiential processing only up to a point of violating their rational understanding. To be sure, there were participants who always responded rationally. What was impressive about the study, however, was the greater number who responded irrationally despite knowing better (in their rational systems).

To determine whether children who have not had formal training in ratios have an intuitive understanding of ratios, we conducted a series of studies in which we examined children’s responses to the ratio-bias experimental paradigm (Yanko & Epstein, 2000). We were also interested in these studies in determining whether children who have only an intuitive understanding of ratios exhibit compromises between the two systems. We found that children without formal knowledge of ratios had only a rudimentary comprehension of ratios. They responded appropriately to differences between ratios only when the magnitude of the differences was large. Like adults, children exhibited compromises, but their compromises were more in the experiential direction. For example, many children but no adults selected a 5% numerousness-advantaged bowl over a 10% probabilityadvantaged one. However, very few of the same children selected a 2% numerousness-advantaged bowl over a 10% probability-advantaged one.

We also used the ratio-bias experimental paradigm to test the assumption in CEST that the experiential system responds to visual imagery in a way similar to the way it does to real experience (Epstein & Pacini, 2001). We presented participants in an experimental group with a verbal description of the ratio-bias experimental paradigm after training them to vividly visualize the situation. Participants in the control group were given only the verbal description. In support of the assumption, the visual-imaging group but not the control group exhibited the ratio-bias phenomenon in a manner similar to what we have repeatedly found in real situations but not in simulated situations.

The overall results from the many studies we conducted with the ratio-bias paradigm (Denes-Raj & Epstein, 1994; Denes-Raj, Epstein, & Cole, 1995; Kirkpatrick & Epstein, 1992; Pacini & Epstein, 1999a, 1999b; Yanko & Epstein, 2000) provided support for the following assumptions and hypotheses derived from CEST. There are two independent information-processing systems. Sometimes they conflict with each other, but more often they form compromises. With increasing maturation from childhood to adulthood, the balance of influence between the two processing systems shifts in the direction of increased rational dominance. The experiential system is more responsive than is the rational system to imagery and to other concrete representations than the rational system, whereas the rational system is more responsive than is the experiential system to abstract representations. Engaging the rational system in children who do not have formal knowledge of ratios by asking them to give the reasons for their responses interferes with the application of their intuitive understanding of ratios, resulting in a deterioration of performance.

We have also used the ratio-bias phenomenon to elucidate the thinking of people with emotional disorders. In a study of depressed college students (Pacini, Muir, & Epstein, 1998), the ratio-bias phenomenon helped to clarify the paradoxical depressive-realism phenomenon (Alloy & Abramson, 1988). The phenomenon refers to the finding that depressed participants are more rather than less accurate than are nondepressed participants in judging contingencies between events. We found that the depressed participants made more optimal responses than did their nondepressed counterparts only when the stakes for nonoptimal responding were inconsequential. When we raised the stakes, the depressed participants responded more experientially and the control participants responded more rationally, so that the groups converged and no longer differed. We concluded that the depressive-realism phenomenon can be attributed to an overcompensatory reaction by subclinically depressed participants in trivial situations to a more basic tendency to behave unrealistically in emotionally significant situations. We further concluded that normal individuals tend to rely on their less demanding experiential processing when incentives are low, but increasingly engage their more demanding rational processing as incentives are increased.

The Global-Evaluation Heuristic

The global-person-evaluation heuristic refers to the tendency of people to evaluate others holistically as either good or bad people rather than to restrict their judgments to specific behaviors or attributes. Because the global-personevaluation heuristic is consistent with the assumption that holistic evaluation is a fundamental operating principle of the experiential system (see Table 7.1), it follows that globalperson-evaluations tend to be highly compelling and not easily changed. The heuristic is particularly important because of its prevalence and because of the problems that arise from it—such as when jurors are influenced by the attractiveness of a defendant’s appearance or personality in judging his or her guilt. An interesting example of this phenomenon was provided in the hearing of Clarence Thomas for appointment to the United States Supreme Court. The testimony by Anita Hill about the obscene sexual advances she alleged he made to her was discredited in the eyes of several senators because of the favorable testimony by employees and acquaintances about his character and behavior. It seemed inconceivable to the senators that an otherwise good person could be sexually abusive.

We studied the global-person-evaluation heuristic (reported in Epstein, 1994) by having participants respond to a vignette adapted from a study by Miller and Gunasegaram (1990). In the vignette, a rich benefactor tells three friends that if each throws a coin that comes up heads, he will give each $100. The first two throw a heads, but Smith, the third, throws a tails. When asked to rate how each of the protagonists feels, most participants indicated that Smith would feel guilty and the others would feel angry with him. In an alternative version with reduced stakes, the ratings of guilt and anger were correspondingly reduced. When asked if the other two would be willing, as they previously had intended, to invite Smith to join them on a gambling vacation in Las Vegas, where they would share wins and losses, most participants said they would not “because he is a loser.” These responses were made both from the perspective of how the participants reported they themselves would react in a real situation and how they believed most people would react. When responding from the perspective of how a completely logical person would react, most participants said a logical person would recognize that the outcome of the coin tosses was arbitrary, and they therefore would not hold it against Smith. They further indicated that a logical person would invite him on the gambling venture.

This study indicates that people tend to judge others holistically by outcomes, even arbitrary ones. It further indicates that people intuitively recognize that there are two systems of information processing that operate in a manner consistent with the principles of the experiential and rational systems. It also supports the hypotheses that experiential processing becomes increasingly dominant with an increase in emotional involvement and that people overgeneralize broadly in judging others on the basis of outcomes over which the person has no control, even though they know better in their rational system.

Conjunction Problems

The Linda conjunction problem is probably the most researchedvignetteinthehistoryofpsychology.Ithasevoked a great deal of interest among psychologists because of its paradoxical results. More specifically, although the solution to the Linda problem requires the application of one of the simplest and most fundamental principles of probability theory, almost everyone—including people sophisticated in statistics—gets it wrong. How is this to be explained?As you might suspect by now, the explanation lies in the operating principles of the experiential system.

Linda is described as a 31-year-old woman who is single, outspoken, and very bright. In college she was a philosophy major who participated in antinuclear demonstrations and was concerned with issues of social justice. How would you rank the following three possibilities: Linda is a feminist, Linda is a bank teller, and Linda is a feminist and a bank teller? If you responded like most people, you ranked Linda as being a feminist and a bank teller ahead of Linda’s being just a bank teller. In doing so, you made what Tversky & Kahneman (1982) refer to as a conjunction fallacy, and which we refer to as a conjunction error (CE). It is an error or fallacy because according to the conjunction rule, the occurrence of two events cannot be more likely than the occurrence of only one of them.

The usual explanation of the high rate of CEs that people make is that they either do not know the conjunction rule or they do not think of it in the context of the Linda vignette. They respond instead, according to Tversky and Kahneman, by the representativeness heuristic, according to which being both a bank teller and a feminist is more representative of Linda’s personality than being just a bank teller.

In a series of studies on conjunction problems, including the Linda problem (Donovan & Epstein, 1997; Epstein, Denes-Raj, & Pacini, 1995; Epstein & Donovan, 1995; Epstein, Donovan, & Denes-Raj, 1999; Epstein & Pacini, 1995), we concluded that the major reason for the difficulty of the Linda problem is not an absence of knowledge of the conjunction rule or a failure to think of it. We demonstrated that almost all people have intuitive knowledge of the conjunction rule, as they apply it correctly in natural contexts, such as in problems about lotteries. Nearly all of our participants, whether or not they had formal knowledge of the conjunction rule, reported that winning two lotteries, one with a very low probability of winning and the other with a higher probability, is less likely than is winning either one of them (Epstein et al., 1995). This finding is particularly interesting from the perspective of CEST because it indicates that the experiential system (which knows the conjunction rule intuitively) is sometimes smarter than the rational system (which may not be able to articulate the rule).We also found that when we presented the conjunction rule among other alternatives, thereby circumventing the problem of whether people think of it in the context of the Linda problem, most people selected the wrong rule. They made the rule fit their responses to the Linda problem rather than the reverse, thereby demonstrating the compelling nature of experiential processing and its ability to dominate analytical thinking in certain situations.

The conclusions from our series of studies with the Linda problem can be summarized as follows:

- The difficulty of the Linda problem cannot be fully accounted for by the misleading manner in which it is presented, for even with full disclosure about the nature of the problem and the request to treat it purely as a probability problem, a substantial number of participants makes CEs. Apparently, people tend to view the Linda problem as a personality problem rather than as a probability problem, no matter what they are told.

- The difficulty of the Linda problem can be explained by the rules of operation of the experiential system, which is the mode employed by most people when responding to it. Thus, people tend to reason associatively, concretely, holistically, and in a narrative manner rather than abstractly and analytically when responding to the For example, a number of participants explained their responses that violated the conjunction rule by stating that Linda is more likely to be a bank teller and a feminist than just a feminist because she has to make a living.

- The essence of the difficulty of the Linda problem is that it involves an unnatural, concrete presentation, where an unnatural presentation is defined as one that differs from the context in which a problem is normally presented. We found that concrete presentations facilitate performance in natural situations (in which the two processing systems operate in synchrony) and interfere with performance in unnatural situations (in which the two systems operate in opposition to each other).

- Processing in the experiential mode is intrinsically highly compelling and can override processing in the rational mode even when the latter requires no more effort. Thus, many people, despite knowing and thinking of the conjunction rule, nevertheless prefer a representativeness solution.

- Priming intuitive knowledge in the experiential system can facilitate the solution to problems that people are unable initially to solve intellectually.

Interaction Between the Two Processing Systems

An important assumption in CEST is that the two systems are interactive. Interaction occurs simultaneously as well as sequentially. Simultaneous interaction was demonstrated in the compromises between the two systems observed in the studies of the ratio-bias phenomenon. Sequential interaction was demonstrated in thestudy in which people listedtheir first three thoughts and in the studies of conjunction problems, in which presenting concrete, natural problems before abstract problems facilitated the solution of the abstract problems.

There is also considerable evidence that priming the experiential system subliminally can influence subsequent responses in the rational system (see review in Bargh, 1989). Other evidence indicates that the form independent of the content of processing in the rational system can be influenced by priming the experiential system. When processing in the experiential mode is followed by attempts to respond rationally, the rational mode itself may be compromised by intrusions of experiential reasoning principles (Chaiken & Maheswaren, 1994; Denes-Raj, Epstein, & Cole, 1995; Edwards, 1990; Epstein et al., 1992).

Sequential influence does not occur only in the direction of the experiential system influencing the rational system. As previously noted, in everyday life sequential processing often proceeds in the opposite direction, as when people react to their irrational, automatic thoughts with corrective, rational thoughts. In a study designed to examine this process, we instructed participants to list the first three thoughts that came to mind after imagining themselves in various situations described in vignettes (reported in Epstein, 1994). The first response was usually a maladaptive thought consistent with the associative principle of the experiential system, whereas the third response was usually a more carefully reasoned thought in the mode of the rational system. As an example, consider the responses to the following vignette, which describes a protagonist who fails to win a lottery because she took the advice of a friend rather than follow her own inclination to buy a ticket that had her lucky number on it. Among the most common first thoughts were that the friend was to blame and that the participant would never take her advice again. By the third thought, however, the participants were likely to state that the outcome was due to chance and no one was to blame.

Interaction Between the Basic Needs

You will recall that a basic assumption in CEST is that behavior often represents a compromise among multiple basic needs. This process is considered to be particularly important, as it provides a means by which the basic needs serve as checks and balances against each other, with each need constrained by the influence of the other needs. To test the assumption about compromises, we examined the combined influence of the needs for self-enhancement and self-verification. Swann and his associates had previously demonstrated that the needs for enhancement and verification operate sequentially, with the former tending to precede the latter (e.g., Swann, 1990; Hixon & Swann, 1993). We wished to demonstrate that they also operate simultaneously, as manifested by compromises between them. Our procedure consisted of varying the favorableness of evaluative feedback and observing whether participants had a preference for feedback that matched or was more favorable to various degrees than their self-assessments (Epstein & Morling, 1995; Morling & Epstein, 1997). In support of our hypotheses, participants preferred feedback that was only slightly more favorable than their own selfassessments, consistent with a compromise between the need for verification and the need for self-enhancement.

Research on Individual Differences

Individual Differences in the Intelligence of the Experiential System

If there are two different systems for adapting to the environment, then it is reasonable to suspect that there are individual differences in the efficacy with which people employ each. It is therefore assumed in CEST that each system has its own form of intelligence. The question remains as to how to measure each. The intelligence of the rational system can be measured by intelligence tests, which are fairly good predictors of academic performance. To a somewhat lesser extent, they also predict performance in a wide variety of activities in the real world, including performance in the workplace, particularly in situations that require complex operations (see reviews in Gordon, 1997; Gottfredson, 1997; Hunter, 1983, 1986; Hunter & Hunter, 1984). However, intelligence tests do not measure other kinds of abilities that are equally important for success in living, including motivation, practical intelligence, ego strength, appropriate emotions, social facility, and creativity.

Until recently, there was no measure of the intelligence of the experiential system; one reason for this is that the concept of an experiential system was unknown. Having established its theoretical viability, the next step was to construct a way of measuring it, which resulted in the Constructive Thinking Inventory (CTI; Epstein, 2001). The measurement of experiential intelligence is based on the assumption that experiential intelligence is revealed by the adaptiveness of the thoughts that tend to spontaneously occur in different situations or conditions.

People respond to the CTI by reporting on a 5-point scale the degree to which they have certain common adaptive and maladaptive automatic or spontaneous thoughts. An example of an item is I spend a lot of time thinking about my mistakes, even if there is nothing I can do about them (reverse scored).