View sample cognitive development in childhood research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

As a distinct subfield of developmental psychology, cognitive development has about a 50-year history. Prior to the 1950s, the field had few specialists in cognitive development. A related area, the study of learning in children, goes back to the beginnings of the field (e.g. see Thorndike, 1914; Watson, 1913), but the theoretical frameworks within which the study of learning was carried out differ sharply from those that came to prominence after about the middle of the twentieth century. Learning was conceptualized primarily in terms of behavioral principles and association processes, whereas cognitive development emerged from the cognitive revolution, the revolution in psycholinguistics, and especially Piaget’s work on children’s reasoning about a myriad of subjects like space, time, causality, morality, and necessity (Kessen, 1965; Piaget, 1967, 1970).Therefore, although superficially similar, research and theory on learning versus research and theory on cognitive development represent very different histories and very different perspectives.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The present research paper deals mainly with broader theories that have been devised to try to explain how the mind grows and transforms. Its time frame extends from about the middle of the twentieth century to the present time. It does not deal directly with related topics in cognitive psychology such as learning, perception, attention, motivation, and memory; these are seen as more properly belonging to the larger field of cognition, of which cognitive development represents a part of the overall story (Flavell, 1977). Language development has emerged as a substantial research topic in its own right, and although closely related to more general issues in cognitive development, it is now a specialty area large enough to merit separate treatment. Its roots are separate as well, springing from the debates between behaviorism and nativism as explanations for language acquisition. Indeed, there are specialists in cognitive development who may not know a great deal about language development, and (although less likely) vice versa.

Three Revolutions

The field of cognitive development became a separate area of developmental psychology largely as a consequence of three sets of related events that all occurred around the middle of the last century: the cognitive revolution (Bruner, 1986; Gardner, 1985; Miller, 1983), the language revolution (Chomsky, 1957), and the Piagetian revolution (Flavell, 1963; Piaget, 1970).All three of these revolutions had the quality in common that they opened up the black box, so to speak, of the mind and set as a goal the exploration of the mental processes and mental structures that control thought—particularly human thought. Prior to these revolutions, psychology (at least on the North American continent) was largely dominated by behavioristic and positivistic perspectives that eschewed what they viewed as speculation about the inner workings of the mind (Boring, 1950; Gardner, Kornhaber, & Wake, 1996).As the combined effects of the three new approaches accumulated, the study of mental processes, how they work, and how and why they develop became central to the field of developmental psychology. Thus emerged the new specialty of cognitive development.

Each of the three revolutions had important influences on the form that the field of cognitive development would take. Although there were other influences to be sure, it is fair to say that the end of the 1960s largely set the shape and contour of cognitive development as a field of study. Although any one of the three might have been sufficient to inspire a new specialty in cognitive development, it is the synergistic impact of the three that gives the field its distinctive form.

Because of its central role in the field and because of its continuing influence on all areas of cognitive development, this research paper focuses on Piaget and the Genevan tradition, summarizing its main contributions and the main lines of criticism that have been mounted in recent decades. Although three revolutions gave rise to the field of cognitive development, one of them (the Piagetian revolution) has been so far the most influential and most enduring.

Prior to 1960, few scholars labeled themselves as cognitive developmentalists. From 1960 through the end of the century, hundreds of scholars were trained in and pursued research careers in cognitive development, largely because of the excitement and challenge of the work done in Geneva.

After briefly reviewing some of the main features of the other two primary sources of inspiration for the field of cognitive development, a more detailed review of the Piagetian system and its features are presented.

The Cognitive Revolution

From the newly emerging field of cognition, the assumption that there are important mediating processes that internally organize and direct behavior was integrated into the study of cognitive development from the start. The study of cognition focused on control of motor processes, perception, attention, association, and memory—processes too fine-grained for most cognitive developmentalists. But topics like problem solving strategies, hypothesis formation, skill acquisition, skill sequences, classification, and hierarchical organization processes have been of great interest to researchers and theorists in the field (e.g., Brainerd, 1978; Case, 1972; Fischer, 1980; Flavell, 1977; Klahr, 1984; Siegler, 1981, 1996). The field rapidly broadened its reach to embrace some more socially and culturally weighted topics like social cognition and moral reasoning (e.g., Ainsworth, 1973; Kohlberg, 1973; Miller, 1983). The hallmark of virtually all research inspired by the study of cognition has been its emphasis on identifying, describing, and explaining the inner workings of thought, the ways in which thought evolves, and how knowledge and understandings are achieved. These more general issues are prominent in most research and theory in cognitive development.

The Revolution in Language Acquisition

The influence of the revolution in language was essentially twofold: It showed that mentalistic approaches to speech were necessary; also, it proposed that linguistic structures were innate and required no special environmental circumstances for them to appear. With Chomsky’s publication of Syntactical Structures (1957), the identification of a set of mental rules that guide the production of an infinity of speech forms helped transform the study of language from a behaviorally oriented to a mentally oriented enterprise. Chomsky’s debates with Skinner and others (e.g., Chomsky, 1972) cracked the hold that behavioral analysis held on the field of research on language and successfully questioned the adequacy of association rules to account for the diversity of speech forms that exist.

The second major influence of cognitive linguistics was less immediate in its impact but no less important. A central assumption of the approach of Chomsky and his followers was that linguistic rules are native and natural to human beings. It assumed that human beings come into the world equipped with a language acquisition device or language module that contains all the information necessary for each individual to become a user of human speech (barring organic deficit, of course; Bruner, 1986; Chomsky, 1957; Piattelli-Palmerini, 1980).

With the nativist assumption as its inspiration, the seeds were planted for two important strains of work to germinate. One attempted to specify the nature of innate modules for various forms of human thought beyond speech (e.g., face recognition, space, music, dance, time, quantity) and the rules that underlie each module (Carey, 1985; Fodor, 1980, 1983; Gardner, 1983; Keil, 1984, 1989). Another strain set out to establish the existence of abilities and skills, including theories and ontological distinctions present even in the earliest months of life (e.g. Gelman, 1998; Gopnik & Meltzoff 1997; Spelke & Newport, 1998). Thus, along with a set of core domains and privileged content areas, the field began to seek a set of core cognitive capabilities, some of which are quite sophisticated, that are natural to human minds from the outset (Bates, Thal, & Meacham, 1991; Gelman, 1998; Greenfield, 2001; Spelke, 2001). These lines of work in turn were challenging to the Piagetian tradition and led to reaction and response from both sides (see Piattelli-Palmerini, 1980).

Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence

Although not quite as influential, two other areas of research—one that predates the field of cognitive development and the other appearing at about the same time—need to be mentioned to complete the picture of the main ingredients of the field during its 50-year history. The study of intelligence (usually expressed in IQ or G terms) dates from at least the beginning of the twentieth century and has provided a foil against which other approaches to cognitive development have railed. The effort to simulate cognitive processes using computer programming techniques has in turn provided a demanding criterion against which claims for the adequacy of accounts of cognitive development have often been evaluated.

The field of artificial intelligence has added a degree of rigor and precision to many of the efforts to study particular instances of problem solving or skill acquisition (e.g., Siegler, 1981, 1984). Essentially, if a team of researchers is successful in getting a computer to behave in ways that support their claims for a learning process of a particular kind, their claims are supported by the accomplishment. More recently, the study of simulated neural networks has provided a challenge that is (in certain respects) even more demanding than efforts to explain transformation and change in cognitive structures through computer simulation (Elman et al., 1996; J. A. Feldman, 1981; Plunkett & Sinha, 1992).

The Piagetian Revolution

As John Flavell (1998) has written of Piaget (quoting another source), estimating the influence of Piaget on developmental psychology is like trying to estimate the influence of Shakespeare on English literature. In other words, Piaget’s impact was (and in many respects still is) incalculable. For the study of cognitive development, three influences have been particularly important for the direction in which the field has gone; these influences are the emphasis on the development of universal cognitive structures, the claim that all cognitive structures are constructed by the individual child (neither taught by others nor innate), and the necessity of explaining novel structures through processes that account for transitions from earlier and less powerful to later and more powerful forms of reasoning (Beilin, 1985; Piaget, 1963, 1970, 1971b).

Other important influences of Piaget and the Genevan research enterprise include the increasing emphasis on explaining changes in logical reasoning as the central goal of the work, the tendency to study scientific reasoning (space, time, causality, necessity) over other possible topics (e.g., learning school subjects, artistic areas, physical development), and a tendency to de-emphasize the importance of language and thus separate mainstream cognitive development work from work on language acquisition.

When Piaget began his work in the early 1920s, he worked as an assistant in the laboratory of T. H. Simon, the French researcher who was the co-inventor of the standardized intelligence test (Bringuier, 1980; Gardner et al., 1996). Piaget found the psychometric approach to intelligence deeply problematic and quite intentionally set out to define intelligence in a very different way.

Rather than finding out whether children know the right answers to standard questions, Piaget believed that children’s reasoning and the ideas that they generated were of greater interest than was the correctness of their responses. And he found the set format of psychometric procedure to be confining and constraining in what could be discovered about the child’s mind and how it deals with the challenges of the world (Gardner et al., 1996).

Piaget’s efforts to redefine intelligence as the development of cognitive structures of a certain sort has not been completely successful; most people—professional and nonprofessional alike—would still say that intelligence is the quality estimated by IQ tests (Neisser et al., 1996).

Cognitive Development as a Separate Field

The field of cognitive development split off from the field of psychometric intelligence virtually from its beginnings in Geneva. Each approach to intelligence was pursued largely without regard to the other. By the late 1960s or early 1970s, most people in the field of cognitive development would not have considered psychometric studies of intelligence as part of their field of study—and vice versa for those whose work was primarily psychometric; they would have identified themselves as belonging to the field of individual differences or differential psychology. Only during the most recent decades have there been serious efforts to bring the two approaches to intellectual development into a productive relationship (e.g., Elkind, 1976; Fischer & Pipp, 1984; Gardner, 1983, 1993).

Piaget’s work and the work of his many colleagues and collaborators was well known before the 1950s. Piaget’s first five books, written during the 1920s and 1930s, were widely read and often quoted. It was not until the publication of John Flavell’s influential text on Piaget appeared in 1963, however, that a major shift in orientation occurred. Prior to the Piagetian breakthrough, the field of learning was dominated by behaviorally oriented learning paradigms such as those proposed by Pavlov, Thorndike, Watson, and Skinner. Psychometrics was influential in the applied areas of education, business, the military and civil service, but—as mentioned previously—was largely seen as a separate field from the study of learning and problem solving. Although there were no doubt other influences, Flavell’s book on Piaget seemed to catalyze a dramatic shift from behavioral theory to cognitive constructivism as the consensus paradigm for the emerging field (Flavell, 1963).

In arguing that Piaget’s work deserves the most serious study, Flavell (1963) warned against dismissing the theory too hastily:

Piaget’s system is susceptible to a malignant kind of premature foreclosure. You read his writings, your eye is drawn at once to its surface shortcomings, and the inclination can be very strong to proceed no further, to dwell on these. . . . A case could be made that Piaget’s system has suffered precisely such a fate for a long time, and that only recently has there been any sustained effort to resist the siren of criticism in favor of trying to extract underlying contributions. (p. 405)

Partly through efforts like those of Flavell and partly because of the joint influence of the other shifts in fields like linguistics and cognition, the field of child development rushed toward Piaget and the Genevan school with great energy, both positive (e.g., Ginsburg & Opper, 1988; Green, Ford, & Flamer, 1971; Murray, 1972; Tanner & Inhelder, 1971) and negative (e.g., Bereiter, 1970; Brainerd, 1978; Gelman, 1969; Trabasso, Rollins, & Shaughnessy, 1971). The 1960s and 1970s saw a veritable torrent of studies, reviews, books, and articles replicating, extending, challenging, and attempting to apply Piagetian theory and research. In the 1970 edition of Carmichael’s Manual of Child Psychology (Mussen, 1970), Piaget had his own chapter, the only instance in which a contemporary figure wrote about his or her own work (Piaget, 1970). Piaget was cited 96 times in the index of the volume, with a number of the citations being several pages long—a far greater representation than that for any other single figure; Freud was cited 20 times, all single-page citations, and Erik Erikson was cited twice. Jerome Bruner, who helped establish the influence of Piaget with his own brand of constructivist cognitive development, was cited 60 times in the Manual.

By the next edition of the Handbook of Child Psychology (Mussen, 1983), an entire volume was devoted to cognitive development (with John Flavell as one of its editors), and Piaget’s citations had increased to 113, with the word passim added 22 times (compared with none in 1970). Clearly, Piaget’s importance in the field of cognitive development was very evident in how the field responded to his work. Six of the 13 chapters in the 1983 Manual were directly based on work done in or inspired by Genevan research and theory. A separate field within child development had been established largely based on Piaget’s work.

In the most recent edition of the Handbook of Child Psychology (Damon, 1998), the number of citations of Piaget is still high, but there are fewer than in the previous edition; this may be for several reasons, but it is fair to say that the place of Piaget’s work at the center of the field was shaken from its place until recently. More generally, the field of cognitive development itself has shown some signs of diminished visibility. In the current decade cognitive development has had a tendency to show signs of waning as a major subfield of developmental psychology, perhaps because more specialized areas like brain development, neonativist frameworks, language development, artificial intelligence, and dynamic systems approaches have moved to center stage.

Piaget’s enormous influence began to lessen after his death in 1980, when Vygotsky’s more sociocultural approach to development began to eclipse Piaget’s as the century moved toward its final decade (Bruner, 1986). Although still arguably a cognitive developmentalist, Vygotsky’s framework could be equally plausibly thought of as social, cultural, historical, or educational as easily as it could be called cognitive (Glick, 1983; Vygotsky, 1978).

More recently, Genevan work has been gaining attention again in the field as efforts to explain, extend, elaborate and—where necessary—modify Piaget’s theory have shown increasing momentum (e.g., Beilin, 1985; Case, 1991; D. H. Feldman, 2000; Fischer, 1980; Flavell, 1998; Gelman, 1979). Examining how the theory has waxed and waned is a productive way to follow the movements of the field of cognitive development.

Main Features of the Piagetian System

The features of Piaget’s system that found their way to wide acceptance in the study of cognitive development are too numerous to mention, but five seem particularly important. These are (a) an emphasis on universals in the development of cognitive structures; (b) an assumption that there are invariant sequences of stages and substages in cognitive development; (c) transitions between stages and substages must be explained, particularly given the assumption that there are a number of broad, qualitative advances in reasoning structures; (d) the main goal of cognitive development is to acquire a set of logical structures that underlie reasoning in all domains, including space, time, causality, number, and even moral judgment; and (e) that all new structures are constructed by the individual child, who seeks to understand the world in which she or he lives, rather than imposed from the outside by the environment or expressed as a direct biological function of growth.

Universals

The study of child development has tended to focus on normative and general qualities of children as they grow up, but that tendency did not extend to intellectual development until Piaget’s work became prominent. Partly to develop an antidote to what he considered to be an unhealthy emphasis on differences between and among individual children, Piaget wanted to build a theory of cognitive development that would show the common patterns of intellectual development that are shared—regardless of gender, ethnicity, culture, or history.

By choosing to study universals, Piaget and his group showed that every human being is naturally curious and a naturally active learner, sufficiently well equipped to construct all of the essential cognitive structures that characterize the most powerful mind known. In other words, Piaget sacrificed the ability to shed light on differences between and among individuals (see Bringuier, 1980) in order to shine a beam on those qualities that are distinctive to the growing human mind generally. In Piaget’s world, all children are equally blessed with the necessary equipment to build a set of cognitive structures that are the equal of any ever constructed.

Invariant Sequence

The assumption of invariant sequence gives direction and order to cognitive development. The idea that a child must begin with the first set of challenges in a given area and then move in order through to the last step was a powerful claim that generated a great deal of reaction. There are those within the Genevan inner circle who began to back away from the strong form of the claim, especially when data from studies around the world cast doubt on the accuracy of the claim that all children go through a sequence of four large stages from sensorimotor (ages 0–18 months), to preoperational (2–6 years), to concrete operations (6–12 years), to formal operations (about 12 years onward).

Less controversial—but still very important to the theory—are a number of sequences that describe progress of certain more limited concepts such as the object concept, seriation, and many others (Bringuier, 1980; Ginsburg & Opper, 1988; Piaget, 1977).Although some Genevans backed away from the stronger claims of the sequence of stages of the theory (see Cellerier, 1987; Karmiloff-Smith & Inhelder, 1975; Sinclair, 1987), it appears that Piaget never relaxed his claim that all normal children go through the four large-scale stages, reaching the final stage sometime during adolescence (D. H. Feldman, 2000). In a film made a few years before he died, Piaget mentioned stages and sequences more than a dozen times (Piaget, 1977).

Transitions

Perhaps the most controversial feature of Piagetian theory is its mechanism for trying to account for movement from one stage to another (at whatever level of generality the stage is proposed). For this purpose, Piaget borrowed and adapted ideas primarily from the fields of biology and physics. His main goal in proposing the so-called equilibration model was to offer a plausible account of qualitative change in the structures underlying the child’s reasoning that were neither empirical nor innate in origin (e.g., see Piattelli-Palmarini, 1980).

For Piaget, the only kind of transition process that made sense was one that put an active, curious, goal-oriented child at the center of the knowledge-seeking enterprise—a child that would make sustained efforts to build representations and interpretations that became ever more veridical and adaptive of the objects in the world (Bringuier, 1980). Piaget assumed that a child seeks to build accurate representations of the objects important to her or him and to build powerful systems of interpretation to better understand these objects and their relationships to one another and to the child him- or herself.

The notions of equilibrium and systems dynamics from physics were integrated with notions of adaptation and organization from biology to form a mechanism for accepting relevant information (accommodating) and interpreting it using available categories, rules, hierarchies, and conceptual properties available at the time (assimilating). Change in the available instruments for knowing the world come about when existing ways to interpret things are perceived to be inadequate and an apprehension that better ones must be constructed provides needed motivation. The readiness of a growing cognitive system to undergo change is assumed to include some maturational readiness to enable the system to transform, along with sustained efforts on the part of the child to bring about changes perceived to be essential to additional understanding of the world.

Piaget’s theory assumed that the equilibration process is a lifelong effort representing more or less stable outcomes of the functional invariants of organization and adaptation that are the inherent goals of all efforts to build cognitive structures. The effort is never complete; rather, moves through a sequence of four systemwide transformations, resulting in a set of formal organizational structures that provide the most powerful means of understanding the world available to human minds.

It should be noted that Piaget was never fully satisfied with his efforts to account for transitions (e.g., see Bringuier, 1980; Piaget, 1975). One of the last projects he took on was his revision of the equilibration model, an indication of just how vital he felt this aspect of the theory was to its success.

Logical Structures

For Piaget, the ability to use the rules and principles of logical reasoning was the hallmark and the highest goal of human cognitive development. He did not necessarily mean by logical reasoning the set of formal algorithms and techniques of the professional logician. Closer to his meaning would be to describe the goal of cognitive development to be a mind that functions like a well-trained natural scientist— with widespread use of systematic, hypothetico-deductive reasoning: hypothesis testing, experimental design, appropriate methods for gathering information, and rigorous standards of proof. It is not too great a distortion of Piaget’s intent to describe the end of his cognitive developmental model as the mind of a biologist, mathematician, chemist, or physicist.

Later in his career, Piaget began to believe that he had perhaps overly emphasized formal logic as an appropriate reference for the kinds of cognitive structures his last stage represented (see Beilin, 1985; Ginsburg & Opper, 1988). He explored a number of alternative processes and frameworks that might better capture his image of what the formal operations stage is about (e.g., Ginsburg & Opper, 1988; Inhelder, de Caprona, & Cornu-Wells, 1987; Piaget, 1972). Thus the term logical for the final stage in Piaget’s system may be less adequate than originally thought, but what seems clear is that Piaget never abandoned his belief that all children achieve a version of formal operations. He thought this in spite of the fact that many scholars—including some within his own inner circle—began to doubt this claim (e.g., see Beilin, 1985; Commons, Richards, & Ammons, 1984; D. H. Feldman, 2000; Inhelder et al., 1987).

Constructivism

If there has been a triumph of the Genevan school, it is no doubt its emphasis on constructivist explanations of cognitive development. Prior to Piaget, most approaches to mind were either empiricist or rationalist in nature. That is to say, either it was assumed that the child’s mind was a function of the specific history of experiences that formed it, including systematic events in the environment (e.g., sunrise and sunset), purposeful efforts to shape the mind (e.g., teaching, discipline, etc.), or chance events (e.g., accidents, earthquakes, war, etc.); or it was assumed that the mind was formed through some process, such as genetic endowment, supernatural intervention, reincarnation, and so on, beyond the control of the individual.

Piaget rejected both of these long-standing sources of explanation, and instead he proposed that mind is constructed as an interaction between a mind seeking to know and a world with certain inherent affordances (Gibson, 1969) that give rise to certain kinds of knowledge. The idea of interaction is intended to go beyond a vacuous invocation that both nature and nurture are involved in development and to try to propose a rigorous set of processes that explain the construction of cognitive structures (see the previous section of this research paper entitled “Transitions”) through logical-mathematical and physical-empirical experience (often labeled operative and figurative in Piagetian theory; see Milbrath, 1998).

Although Piaget’s version of constructivism is not universally accepted, there are few major streams of current cognitive developmental research and theory that do not have constructivist assumptions of one sort or another. Piaget’s then-revolutionary assumptions of a curious, active, knowledge-seeking child, a child who wants to know and understand the world around her or him, is a feature of virtually all major frameworks in the field of cognitive development (e.g., see Damon, Kuhn, & Siegler, 1998; Liben, 1981).

Taken together, the five features of Piagetian theory just described have transformed the landscape of the study of cognitive development. In addition to these features, many other contributions have had major impact. Two of the more important of these are briefly summarized in the following discussion.

In addition to the major strands of the framework, several other features of Piaget’s approach to cognitive development have made their way into the field. Methodologically, Piaget tended to favor small, informal, exploratory forays into new areas. For these purposes Piaget and his colleagues developed what is now called the clinical method, based as it is on the one-on-one interviews that are common in clinical psychology. Over time, the clinical method of the Geneva school evolved into a highly subtle and carefully articulated set of flexible techniques for guiding a dialogue between an inquiring researcher and a participating child (Ginsburg & Opper, 1988). Although not without its own limitations, the clinical method has gained considerable credibility within cognitive developmental research. Many studies use a version of the interview method often complemented with other more traditional methods such as experiments, correlational and crosssectional studies, and longitudinal research. Piaget tended to be skeptical of statistics and large-scale sampling (see Bringuier, 1980), favoring the more interpretive and analytic approach to research.

As part of the effort to reduce the clinical method’s dependence on speech and language abilities, the Genevans invented many ingenious activities and tasks designed to reveal the structures being acquired and the processes used to respond to the challenges posed to children without depending upon the child’s verbal response. Several of these activities (e.g., the balance beam task) have become almost domains of their own, with dozens and dozens of studies done with them both inside and outside the Genevan framework (e.g., Siegler, 1981, 1996). A task requiring children to take different perspectives on a geographical landscape (the three mountains task; is another example of a clever activity that has been used for many different purposes. As is often the case when an approach to research has great influence, its methodological proclivities and its techniques for gathering special information prove to be as (or more!) important than its broad theoretical or empirical claims.

There are many other influences that emanated from the Genevan school. Some of these have become so well integrated into the field that specific citations for Piaget have lessened. This has been particularly true in the study of infant cognitive development, a specialty area that has exploded since Piaget first showed that babies were active, curious, and surprisingly competent (Gopnik, Meltzoff, & Kuhl, 1999; Piaget, 1967). For someone currently just entering the field, it would be difficult if not impossible to trace the Genevan origin of many of the research topics and techniques.

In spite of the pervasive influence that Piaget and his many followers around the world had from the 1960s to the 1980s, as the century moved into its final decades it appeared that Piaget’s central place in the field was waning—perhaps partly because le patron himself died in 1980, or perhaps because the field needed to move forward in different directions. Works that criticized Piaget’s theory and that questioned the empirical findings of the Genevan school had been part of the literature for decades, to be sure, but the weight of the criticism seemed heavier after about 1980.

Jerome Bruner, one of the founders of the cognitive revolution, one of the first cognitive developmentalists, and an admirer of Piaget, wrote about the rising influence of the Russian Vygotsky:

So, while the major developmental thinker of capitalist Western Europe, Jean Piaget, set forth an image of human development as a lone venture for the child, in which others could not help unless the child had already figured things out on his own and in which not even language could provide useful hints about the conceptual matters to be mastered, the major developmentalist of socialist Eastern Europe set forth a view in which growth was a collective responsibility and language one of the major tools of that collectivity. Now, all these years later, Vygotsky’s star is rising in the Western sky as Piaget’s declines. (in Rogoff & Wertsch, 1984, p. 96).

There are several themes in this quote that we discuss in more detail later in the paper, but at this point it is sufficient to note that one of the great leaders in the field of cognitive development was announcing the end of one era (Piaget’s) and the beginning of another (Vygotsky’s). This view was widely accepted at the time.

Problems with Piaget’s Theoryand Efforts to Respond to Them

Criticisms of various aspects of Piaget’s theory and research program ranged from outright dismissal (e.g., Atkinson, 1983; Brainerd, 1978) to general acceptance but with a need for modification (e.g., Case, 1984; D. H. Feldman, 1980; Fischer, 1980; Fischer & Pipp, 1984). There were also vigorous defenses of Genevan positions (e.g., Elkind, 1976; Inhelder & Chipman, 1976; Inhelder et al., 1987).

The main problems with the theory can be summarized as follows:

- The theory claimed that cognitive development was universal but would not specify the role that maturation plays in the process.

- The theory proposed that each stage of cognitive development was a complete system—a structured whole available to the growing child as she or he moved into that stage. Yet empirical results indicated again and again that children were unable to carry out many of the tasks characteristic of a given stage, leading to charges that the theory invoked an “immaculate transition”

that happened but could not be seen (see Siegler & Munakata, 1993).

- Related to the previous point is that other than proposing a six-phase substage sequence for sensorimotor behavior, the subsequent three large-scale stages of the theory had little internal order. This problem gets worse with each stage because each stage increases in the number of years it encompasses—from 2, to 4, to 6, to at least 8 (see D. H. Feldman, 2002).

- Formal operations, the final stage according to the theory, seemed not to be achieved by many adults (see Commons et al., 1984; Piaget, 1972).

- A number of researchers claimed that stages beyond formal operations exist and needed to be added to the theory (e.g., Commons et al., 1984; Fischer, 1980).

- There was widespread dissatisfaction with the equilibration process as an explanation for qualitative shifts from stage to stage (e.g., Brainerd, 1978; Case, 1984; Damon, 1980; D. H. Feldman, 1980, 1994; Fischer & Pipp, 1984; Keil, 1984, 1989; Piattelli-Palmarini, 1980; Snyder & Feldman, 1977, 1984).

- The theory seemed to depend too much on logic as both a framework for describing cognitive structures and as an ideal toward which development was supposed to be aimed (e.g., Atkinson, 1983; Ennis, 1975; Gardner, 1979; Gardner et al., 1996). Areas of development that were not centrally logical (art, music, drama, poetry, spirituality, etc.) seemed to be largely beyond the theory’s compass.

- The methods that the Genevan school favored, although appropriate for exploratory research, lacked the rigor and systematic techniques of traditional experimental science (e.g., see Bringuier, 1980; Gelman, 1969; Ginsburg & Opper, 1988; Klahr, 1984). Its claims were made at such a broad and general level that it was often difficult to put them to rigorous test (Brainerd, 1978, 1980; Case, 1999; Klahr, 1984; Siegler, 1984).

- The theory did not deal with emotions in any systematic way (Bringuier, 1980; Cowan, 1978 text; Langer, 1969; Loevinger, 1976).

- The theory did not deal with individual differences, individuality, or variability (Bringuier, 1980; Case, 1984, 1991; Fischer, 1980; Fischer & Pipp, 1984; Siegler, 1996; Turiel, 1966).

- The theory implied that progress was a natural and inevitable reality of cognitive development, an assumption that seemed to be more and more a relic from the nineteenth century (Kessen, 1984).

- The theory gave little role to cultural, social, technological, and historical forces as major influences on cognitive development (e.g., Bruner, 1972; Bruner, Olver, & Greenfield, 1966; Cole & Scribner, 1981; Rogoff, 1990; Shweder & LeVine, 1984; Smith, 1995). In particular, it seemed to paradoxically both inspire educational reform and at the same time offer no important role for educators (D. H. Feldman, 1980, 1994).

- As a theory that aims to be suitable for formal analysis, Piaget’s framework was found to have serious flaws conceptually, logically, and philosophically (Atkinson, 1983; Bereiter, 1970; Ennis, 1975; Fodor, 1980, 1983; Lerner, 1986; Oyama, 1985, 1999; Piaget, 1970, 1971b; Piattelli-Palmarini, 1980).

These and other criticisms of Piaget’s great edifice eventually weakened its hold on the field and allowed other perspectives to emerge or reemerge. As Case (1999) suggested, Piaget’s theory was so powerful that for several decades it seemed to overwhelm everything else. The empiricist-learning tradition that preceded it in influence was all but swept aside, while the cultural-historical-social tradition inspired by the writings of Marx and Engel was unable to gain a foothold in North American scholarly discourse. As the century drew to a close, however, the field began to apply (or in the case of empiricism, reengage) topics raised in these other approaches to the growing young mind.

Neo-Piagetian Contributions

The dilemma facing the field in the post-Piaget period, as Case (1999) pointed out, was to somehow transcend the major weakness of the theory while preserving its considerable strengths. A number of divergent paths were taken to try to achieve these ends, of which the so-called neo-Piagetians were the earliest and closest to the original Genevan approach. The two most prominent neo-Piagetian theories were those of Robbie Case (1984, 1991, 1999) and Kurt Fischer (1980; Fischer & Kennedy, 1997; Fischer & Pipp, 1984). These theories had much in common but also certain distinct features.

Both Case and Fischer tried to preserve a version of Piaget’s stages, but added features that made them less problematic. In both theories there is a systematic role for biological maturational processes—processes that prepare the brain and central nervous system for the kinds of changes in structure that the theories propose. Here they were trying to reduce the miraculousness of the stage transition process by invoking a physical enabling change to occur in the central nervous system as part of the transition process. Both theories also dropped the structures as a whole requirement for stages, making movement from stage to stage both a more gradual and more variable process. The shift from stage to stage could take place in a number of different content domains and in a variety of molecular sequences.

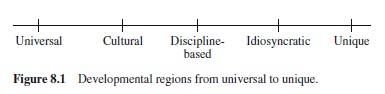

Finally, both Case’s and Fischer’s theories installed a recursive within-stage sequence to help deal with the disorder that was found within Piaget’s stages, particularly those beyond Sensorimotor behavior (see Figure 8.1 for an illustration of how Case’s and Fischer’s theories used recursive substage sequences in the stage architecture).

Although different in detail, both theories proposed a recurring four-phase sequence in each of the major stages (four major stages in Case’s theory and three in Fischer’s). The final phase of each large-scale stage overlaps with the first phase of its more advanced neighbor, becoming integrated into a new kind of organization as the system proceeds forward. This feature helps make transitions less abrupt by showing how elements from a former stage become integral to a more advanced succeeding stage. Thus two problems in the Piagetian formulation are addressed using recursiveness in phases: the lack of order within the large-scale stages and the lack of plausibility of the explanation of how a child moves from large-scale stage to another large-scale stage (Case, 1984, 1991, 1998, 1999; D. H. Feldman, 2000; Fischer, 1980; Fischer & Bidell, 1998).

In these ways (and others) neo-Piagetian theories demonstrated that some of the most intractable problems of Piaget’s formulation could be transcended while still preserving most of the major features of the theory. In order to accomplish these goals, however, both theories focused on more specific contents and narrower sets of processes, losing some of the grandeur and overall sweep of the original. Case’s theory dealt primarily with solving ever more complex and challenging problems through a natural ability to process more kinds of information and construct more complex rules for doing so. Fischer’s theory prescribed a sequence of more and more complex skills that when acquired would allow the child (or young adult) to deal with more and more challenging situations.

As Case (1999) noted, both his and Fischer’s theories explicitly attempted to integrate the broader approach of Piaget with some of the features of the empirical-learning tradition that had been so influential up until the 1960s in North America, with the result that a more variegated, fine-grained pattern could describe each child’s movement through the sequence of broad stages that the theories proposed. Both theories also allowed for greater impact from forces in the child’s environment, thus restoring a major role in cognitive development for parents, caregivers, teachers, and technologies that seemed to have been largely lost in Piaget’s framework (D. H. Feldman, 1976, 1981).

Vygotsky and Sociocultural Theories

While neo-Piagetians and others identified with the rationalist-structuralist tradition attempted to work from within the Piagetian edifice, others were sufficiently disillusioned with the limitations of Genevan theory that they looked elsewhere for inspiration. Partly in response to broader historical and cultural changes (e.g., the end of the Cold War, the civil rights movement, feminism, reactions to excessive greed in the 1980s, etc.), the works of the great Russian developmentalist Lev Vygotsky began to make their way into the mainstream of the field of cognitive development following the translation and publication of his seminal book Thought and Language (sometimes translated as Thinking and Speech; Vygotsky, 1962).

Jerome Bruner (1962) wrote a warm and appreciative foreword to Thought and Language, and Piaget himself (1962) also wrote a set of comments about the work, a rare tribute from Geneva. Michael Cole, Sylvia Scribner, and other scholars (e.g., Cole, Gay, Glick, & Sharp, 1971; Scribner & Cole, 1973) began to promote the work of Vygotsky and other Russian work as having importance for cross-cultural research on intelligence and other topics. The importance of guided assistance from others and the greater role of the social context in promoting or impeding cognitive development were themes of these works that resonated with greater and greater force in the field.

The combination of increasing impatience with some of the limitations and constraints of Piagetian theory along with the refreshing insights into learning based on the wider circle of influence in the Russian work started a groundswell of interest in that work and also inspired new approaches based on Soviet research and theory. Connections heretofore not easily made began to form across disciplines such as anthropology, comparative linguistics, history of science, and cognitive development (e.g., Cole & Means, 1981; Rogoff & Lave, 1984; Shweder & LeVine, 1984). Everyday activities like counting and tailoring that would have seemed irrelevant were suddenly of intense interest to cognitive developmentalists (e.g., Carraher, Carraher, & Schliemann, 1985; Saxe, Guberman, & Gearhart, 1987). Amajor new area of research and theory had been launched and would threaten to eclipse the Piagetian hegemony.

The main features of the Vygotskiian-Russian revolution are an emphasis on shared participation in culturally valued activities, recognition that cultures vary in what kinds of skills and abilities are valued, the importance of culturally constructed and preserved tools and technologies as key to cognitive development, and—in striking contrast to Piaget—the absolutely central role in human cognitive development of language (Cole & Means, 1981; Rogoff & Lave, 1984; Shweder & LeVine, 1984; Vygotsky, 1962, 1978).

This last feature of the sociocultural revolution—the placement of language in the theoretical center of the study of cognitive development—helped make yet another connection that had been waiting to happen since the earliest days of the cognitive revolution. Chomsky (1957, 1972) had claimed that speech was an innate ability, whereas Piaget had claimed that language was no more important than any other symbolic system to be used in constructing cognitive structures (Bringuier, 1980; Piaget, 1970). According to Piaget, speech structures were constructed using the same principles and processes as other symbol systems and were based on the same general procedures created during the first eighteen months of life.

These two powerful claims were apparently sufficient to keep the study of language development largely separate from the rest of the field of cognitive development during most of 50-year period that it has been systematically studied (Brown, 1973; Tomasello, 1992). It was one of Piaget’s strongest convictions that the general procedures for constructing cognitive structures were applied to the challenge of speech as they were applied to the challenge of number, causation, space, time, and many other topics (see Bringuier, 1980). This claim helped support Piaget’s view that human cognitive development shared many of its principles and processes of change with those of other creatures, placing human cognitive development as one among many examples of biological adaptation, neither superior to nor fundamentally different from other examples (Piaget, 1971a, 1971b).

Although this view acknowledged that human cognitive development is distinctive in certain respects (including features like the acquisition of speech and logical reasoning), these features did not set our species above the rest of the organic world. The particular forms that adaptation took in human evolution and individual development represent specific examples of general processes: birdsong and echolocation would be other instances found in other species (Bringuier, 1980; Carey & Gelman, 1991; Piaget, 1971a, 1971b).

Contemporary Trends

As a new century begins, there seems to be less need in the field to insist that humans and other species represent fundamentally similar forms of adaptation to the challenges of survival. Neo-Piagetian theories have proposed systematic biological contributions to the processes of cognitive development without compromising the constructivist core of their frameworks (Case, 1999; Fischer, 1980; Gelman, 1998). There is less of an either-or quality to the discussion about the role of nature versus nurture in development (Gottlieb, 1992; Overton, 1998; Sternberg & Grigorenko, 1997). It is also more widely accepted that biological aspects must be understood as vital to the process of cognitive development (Gardner, 1983). At the same time, the Piagetian assumption is ever more widely accepted that humans construct their own systems for representing and understanding the world and their experience of it (Carey & Gelman, 1991; Gelman, 1998). There are increasing numbers of examples of healthy cross-fertilization between the fields of cognitive development and language development.

The acquisition of speech is now understood to be a remarkable human adaptation, the investigation of which is central to understanding human cognitive development. It is also understood that language, with its powerful evolutionary and natural underpinnings, is constructed through a complex set of processes that are individual, social, cultural, and contextual (Cole & Cole, 1993). Contemporary researchers in language development such as Elizabeth Bates (Bates et al., 1991), Michael Tomasello (1992) and Susan Goldin-Meadow (2000) reflect this trend to draw upon several traditions (Piagetian, Vygotskiian, evolutionary, nativist, computational) to build their frameworks for interpreting language development.

The Universal Versus Individual Cognitive Development

The field of cognitive development for most of its history has been concerned with those sequences of changes that are likely to occur in all children during the course of the first decade or two of life (D. H. Feldman, 1980, 1994; Gelman, 1998; Strauss, 1987). A consequence of this preoccupation with universals is that the variations caused by group or individual differences have tended to be of less interest to the field (Thelen & Smith, 1998). Piaget reflects this view in his response when asked about the individual:

Generally speaking—and I’m ashamed to say it—I’m not really interested in individuals, in the individual. I’m interested in the development of intelligence and knowledge. (Bringuier, 1980, p. 86)

Efforts at Integration

Two recent theories have tried to integrate the general sequences of large-scale changes in cognitive development with modular approaches to mind. The late Robbie Case (1998, 1999; Case & Okamoto, 1996) proposed that general stagelike structures of the Piagetian sort were part but not all of the story of cognitive development. Playing off these universal structures were a set of more content-specific modules of mind, each of which is particularly sensitive to and built to process specific contents. Following from Chomsky’s work in language (1957), a number of modular theories were proposed, usually with several specific kinds of content domains proposed (e.g., Fodor, 1980, 1983; Gardner, 1983, 1993; Karmiloff-Smith, 1992; Keil, 1984, 1989). Examples of proposed modules other than speech that appear in one or more modular theories are music, space, gesture, number, face recognition, and self-other understanding.

In Case’s version of an integrated framework, domainspecific knowledge (as it is often labeled) interacts with systemwide principles and constraints to form what are labeled central conceptual structures. The content-specific nature of the structures in designed to help explain how broad systemwide structures can be formed without resorting to a radical nativist interpretation (Case & Okamoto, 1996). Rather than formed as a consequence of the interaction of a child’s general structures with the objects of the world, central conceptual structures are formed as a consequence of the child’s concern with certain content areas like narrative, number, and space, each of which has distinct constraints and distinct opportunities for learning. Because of the many ways in which the central conceptual structures may be assembled, Case and his colleagues argued that their theory includes room for variation and individuality in the actual course of development (Case & Okamoto, 1996).

A second version of an integrated theory is that of Karmiloff-Smith (1992). In Karmiloff-Smith’s theory, general, systemwide structures are abandoned altogether in favor of a set of content modules that are universal: language; the physical world and how it works; quantity; thought and emotion; and symbolic representation.What remains constant across modules, however, is a set of processes of representing and rerepresenting that give the child the ability to bootstrap from level to level, transcending constraints that each module poses to the developing child.

Using concepts from connectionist modeling in artificial intelligence and dynamic systems approaches (e.g., see Thelen & Smith, 1998), Karmiloff-Smith (1992) has proposed a theory that has both general processes for change and specific-content domains within which such changes take place. Her assumptions are that there are natural, contentspecific constraints on development, but that children construct their understanding of the world through progressive efforts to represent and reinterpret their representations of the knowledge in each domain:

One can attribute various innate predispositions to the human neonate without negating the roles of the physical and sociocultural environments and without jeopardizing the deep-seated conviction that we are special . . . (p. 5).

Athird approach concerns itself with the range and variety of content domains that have been established by human effort without taking a stand one way or another on the issue of modularity (D. H. Feldman, 1980, 1994, 1995). This approach attempts to specify the distinctive markers for categories of domains ranging from universal to unique (see Figure 8.1). The main goal of the effort to specify the qualities that mark domains in each region of the universal to unique continuum of domains is to show that there is vast developmental territory that is not universal, but which is nonetheless developmental in an important sense (i.e., important to individuals, groups, societies, and cultures; D. H. Feldman, 1994).

Nonuniversal theory (as Feldman’s theory is called) aims to provide a framework for knowledge and knowing that encompasses Piaget’s universalist framework and places it into a context of other less universal developmental domains. By describing the levels of various domains in each of the regions of the universal to unique continuum, some of the commonality across domains and some of the distinctiveness of each region and each domain are revealed (van Geert, 1997).

A more recent effort at integration is to be found in the work of Patricia Greenfield (2001). In this framework, the kindofcognitivedevelopmentaltheorythatbestexplainshow children learn and develop is a function of the cultural context within which the processes and activities of learning and development take place. Based on studies in several distinct cultural settings in the United States, Mexico, and Central America, Greenfield and her colleagues have proposed that a more Piagetian framework is most appropriate in cultural context in which economic constraints on learning are minimal, whereas a Vygotskyan framework better captures learning and development when there is pressure to acquire particular skills and techniques to ensure economic well-being.

For Greenfield and her colleagues, there is not a single theory that is a best fit to every cultural context. Rather, different theories will capture the experience of learning and development depending upon the kinds of constraints imposed by the social and cultural contexts that surround them.

The theories just described have in common that they attempt to preserve some of the useful features of approaches like Piaget’s that emphasize universals in cognitive development, while at the same time trying to build into their architecture important variations within and across individuals, groups, societies, and cultures. Case’s approach focuses on how individuals use modules of specified content to construct universal conceptual structures, with the primary aim to better account for general, systemwide change than do previous frameworks. Karmiloff-Smith abandons general, systemwide change in favor of more domain-specific development, but with sequences of processes of change that can be found across domains. Thus, her theory also aims primarily to account for universals in development, but to do so in ways that reconcile nativist and constructivist perspectives.

Nonuniversal theory is primarily intended to illustrate the diversity in developmental domains that may engage the energies of individuals. While recognizing that there are some domainsthatareuniversalornearlyso,asPiagetproposed,the theory proposes that many other domains of knowledge and skill can be conceptualized as developmental in the sense that they are built in sequences of developmental levels and are achieved through change processes that include qualitative shifts in organization and functioning. By drawing attention to common as well as distinct features of various domains, some of which are universally achieved and others of which may be achieved only by members of a species, a culture, a discipline, an avocation, or even an individual, the range of topics of concern to developmentalists is greatly expanded.

Greenfield’s approach is intended less to integrate various theoretical frameworks into a single one, but rather to add a set of broader social and cultural considerations to the discussion of learning and development that help guide the selection of one or another existing theoretical explanation. In this respect, theories are less competing explanations for a single truth, but rather exist as possible sources of truth, understanding, enrichment, and guidance, depending upon the context within which they are used (Greenfield, 2001).

Theories like Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s—in the context of the universal-to-unique continuum of developmental domains—can be better understood as dealing with different kinds of domains: Piaget’s theory is about universals, and Vygotsky’s is about pancultural and cultural domains (D. H. Feldman & Fowler, 1997). Therefore, trying to determine which theory is right and which is wrong misses the essential point that they are about different aspects of developmental change.

Nonuniversal theory is therefore useful in helping make conceptual and theoretical distinctions between and among various theories of cognitive development, but does not focus as much on how qualitative change occurs as do Case’s and Karmiloff-Smith’s theories (van Geert, 1997).

Future Directions in Cognitive Developmental Theory and Research

With more than half a century of productive work behind it, the field of cognitive development seems well established as a specialty area within developmental psychology. Although dominated by the Genevan approach for much of its history, the field has recently reengaged some of its traditional areas of emphasis, such as experimental learning studies and sociocultural-historical research (Case, 1999). It has also spawned some cross-disciplinary efforts to better deal with the challenges of explaining systematic, qualitative change, which is the heart of the matter for cognitive developmentalists. Drawing on work done in systems theory or connectionism from artificial intelligence, a number of contemporary researchers have tried to build frameworks that are complex enough to allow for many levels of description to interact with each other to produce major change (Fischer & Bidell, 1998; Thelen & Smith, 1998; van Geert, 1991, 1997). Efforts to model qualitative change using dynamic systems (Lewis, 2000; Thelen & Smith, 1998; van Geert, 1991) and chaos theory (van der Maas & Molenaar, 1992) have shown promise as sources of explanation for stagelike shifts. By working at a fine grain of detail, dynamic systems and other approaches take a further step toward trying to integrate general and specific, universal and unique, commonality and variation, and description and explanation (Lerner, 1998).

Similarly, research and theory from newly emerging disciplines like evolutionary robotics and artificial life simulations have become important sources of ideas for research and theory in cognitive development (D. H. Feldman, 2002; Norman, 1993; Varela, Thompson, & Rosch, 1993; Wilensky & Resnick, 1999). Starting with simple sensorimotor processes, detailed histories of interactions between and among levels of activity provide rich sources of information about change, including large-scale changes that can occur without changing the simple processes that gave rise to the emergent layers of activity in the system and that sustain it (Bedeau, 1997; Thompson & Fine, 1999).

Therehavealsobeengreatstridesmadeinthetechnologies that permit brain imaging and of studies of the neural basis of brain development and functioning, both of which will no doubt have impact on the field of cognitive development, and perhaps vice versa (Johnson, 1998). The thrust of work in these areas is fully consistent with the direction of other current approaches in being interdisciplinary, systems oriented, interactive, and constructivist (Lerner, 1998). The interactive relations between brain and behavior—each influencing the development of the other within the context of other systems emerging and changing—reflects the growing consensus within the field that all levels of description, from the molecular to the whole organism in context, will be necessary aspects of our efforts to explain cognitive development.

Finally, we may wish to conclude this brief summary of the field of cognitive development by noting that the boundaries and borders between and among aspects of human development have become more permeable (Lerner, 1998). It is increasingly recognized that important influences on cognitive development may come from emotions, motivations, challenges, and environmental events (Bearison & Zimiles, 1986; D. H. Feldman, 1994). Although it seems likely that a field called cognitive development is likely to continue to exist within developmental psychology, the range of topics, the variety of phenomena encompassed, and the degree of interaction with other specialties are all likely to increase in the decades to come. There are without doubt sufficient challenges in the study of cognitive development to keep a cadre of researchers and theorists busy for many decades to come.

Bibliography:

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1973). The development of infant-mother attachment. In B. M. Caldwell & H. N. Ricciuti (Eds.), Review of child development research (Vol. 3, pp. 1–94). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Atkinson, C. (1983), Making sense of Piaget: The philosophical roots. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Bates, E., Thal, D., & Marchman, B. (1991). Symbols and syntax: A Darwinian approach to language development. In N. Krasnegor, D. Rumbaugh, R. Schiefelbusch, & M. Studdert-Kennedy (Eds.), Biological and behavioral determinants of language development (pp. 29–65). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bearison, D., & Zimiles, H. (Eds.). (1986). Thought and emotion: Developmental perspectives. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Bedeau, M. A. (1997). Weak emergence: Philosophical perspectives. Mind, Causation, and World, 11, 374–399.

- Beilin, H. (1985). Dispensable and nondispensable elements in Piaget’s theory. In J. Montangero (Ed.), Genetic epistemology: Yesterday and today (pp. 107–125). New York: City University of New York, The Graduate School and University Center.

- Bereiter, C. (1970). Educational implications of Kohlberg’s cognitive-developmental view. Interchange, 1, 25–32.

- Boring, E. (1950). A history of experimental psychology. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Brainerd, C. (1978). The stage question in cognitive-developmental theory. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 173–182.

- Bringuier, J.-C. (1980). Conversations with Jean Piaget. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Brown, R. (1973). A first language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1962). Introduction. In L. Vygotsky, Thought and language (pp. v–x). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bruner, J. (1972). The nature and uses of immaturity. American Psychologist, 27, 1–22.

- Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J., Olver, R., & Greenfield, P. (1966). Studies in cognitive growth. New York: Wiley.

- Carraher, T. N., Carraher, D. W., & Schliemann, A. D. (1985). Mathematics in the streets and schools. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3, 21–29.

- Carey, S. (1985). Conceptual change in childhood. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Carey, S., & Gelman, R. (Eds.). (1991). The epigenesis of mind: Essays on biology and cognition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Case, R. (1972). Learning and development: A neo-Piagetian interpretation. Human Development, 15, 339–358.

- Case, R. (1984). The process of stage transition: A neo-Piagetian view. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Mechanisms of cognitive development (pp. 19–44). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Case, R. (1985). Intellectual development: Birth to adulthood. New York: Academic Press.

- Case, R. (1991). The mind’s staircase: Exploring the conceptual underpinnings of children’s thought and knowledge. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Case, R. (1998). The development of conceptual structures. In D. Kuhn & R. Siegler (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Perception, cognition, and language (5th ed., pp. 745– 800). New York: Wiley.

- Case, R. (1999). Conceptual development in the child and the field: A personal view of the Piagetian legacy. In E. Scholnick, K. Nelson, S. Gelman, & P. Miller (Eds.), Conceptual development: Piaget’s legacy (pp. 23–51). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Case, R., & Okamoto, Y. (1996). The role of central conceptual structures in the development of children’s thought. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child development, 61 (1–2, Serial No. 246).

- Cellerier, G. (1987). Structures and functions. In B. Inhelder, D. de Caprona, & A. Cornu-Wells (Eds.), Piaget today (pp. 15–36). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. The Hague, The Netherlands: Mouton.

- Chomsky, N. (1972). Psychology and ideology. Cognition, 1, 11–46.

- Cole, M., & Cole, S. (1993). The development of children (2nd ed.). New York: Scientific American Books.

- Cole, M., Gay, J., Glick, J., & Sharp, D. (1971). The cultural context of learning and thinking. New York: Basic Books.

- Cole, M., & Means, B. (1981). Comparative studies of how people think: An introduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cole, M., & Scribner, S. (1981). Culture and thought: A psychological introduction. New York: Wiley.

- Commons, M., Richards, F., & Ammons, C. (Eds.). (1984). Beyond formal operations: Late adolescent and adult development. New York: Praeger.

- Cowan, P. (1978). Piaget: With feeling. NewYork: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

- Damon, W. (1980). Patterns of change in children’s social reasoning. Child Development, 51, 101–107.

- Damon, W. (1998). Preface. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Damon, W., Kuhn, D., & Siegler, R. (Eds.). (1998). Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Elkind, D. (1976). Child development and education: A Piagetian perspective. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Elman, J., Bates, E., Johnson, J., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Parisi, D., & Plunkett, K. (1996). Rethinking innateness: A connectionist perspective on development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ennis, R. (1975). Children’s ability to handle Piaget’s propositional logic: A conceptual critique. Review of Educational Research, 45, 1–41.

- Feldman, D. H. (1976). The child as craftsman. Phi Delta Kappan, 58, 143–149.

- Feldman, D. H. (1980). Beyond universals in cognitive development. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Feldman, D. H. (1994). Beyond universals in cognitive development (2nd ed.). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

- Feldman, D. H. (1995). Learning and development in nonuniversal theory. Human Development, 38, 315–321.

- Feldman, D. H. (2002, June). Piaget’s stages revisited (and somewhat revised). Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Jean Piaget Society, Philadelphia, PA.

- Feldman, D. H., & Fowler, C. (1997). The nature(s) of developmental change: Piaget, Vygotsky and the transition process. New Ideas in Psychology, 15, 195–210.

- Feldman, J. A. (1981). A connectionist model of visual memory. In G. Hinton & J. Anderson (Eds.), Parallel models of associative memory. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Fischer, K. W. (1980). A theory of cognitive development: The control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review, 87, 477–531.

- Fischer, K. W., & Bidell, T. (1998). Dynamic development of psychological structures in action and thought. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 467–561). New York: Wiley.

- Fischer, K. W., & Kennedy, B. (1997). Tools for analyzing the many shapes of development: The case of self-in-relationships in Korea. In K. A. Renninger & E. Amsel (Eds.), Change and development: Issues of theory, method, application (pp. 117–152). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Fischer, K. W., & Pipp, S. (1984). Processes of cognitive development: Optimal level and skill acquisition. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Mechanisms of cognitive development (pp. 45–80). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Flavell, J. (1963). The developmental psychology of Jean Piaget. New York: Van Nostrand.

- Flavell, J. (1977). Cognitive development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Flavell, J. (1998). Piaget’s legacy. In A. Woolfolk (Ed.), Readings in educational psychology (pp. 31–35). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Fodor, J. (1980). On the impossibility of acquiring “more powerful” structures. In M. Piattelli-Palmerini (Ed.), Language and learning: The debate between Jean Piaget and Noam Chomsky (pp. 142–149). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fodor, J. (1983). The modularity of mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gardner, H. (1979). Developmental psychology after Piaget: An approach in terms of symbolization. Human Development, 22, 73–88.

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books.

- Gardner, H. (1985). The mind’s new science: A history of the cognitive revolution. New York: Basic Books.

- Gardner, H., Kornhaber, M., & Wake, W. (1996). Intelligence: Multiple perspectives. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace.

- Gelman, R. (1969). Conservation acquisition: Aproblem of learning to attend to relevant attributes. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 7, 167–187.

- Gelman, R. (1979). Why we will continue to read Piaget. The Genetic Epistemologist, 8, 1–3.

- Gelman, R. (1998). Domain specificity in cognitive development: Universals and nonuniversals. In M. Sabourin, F. Craik, & M. Robert (Eds.), Advances in psychological science: Vol. 2. Biological and cognitive aspects (pp. 557–579). East Sussex, UK: Psychology Press.

- Gibson, E. J. (1969). Principles of perceptual learning and development. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Ginsburg, H., & Opper, S. (1988). Piaget’s theory of intellectual development (3rd ed.). New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Glick, J. (1983). Piaget, Vygotsky, and Werner. In S. Wapner & B. Kaplan (Eds.), Toward a holistic developmental psychology (pp. 51–62). New York: Hudson Hills Press.

- Goldin-Meadow, S. (2000). Beyond words: The importance of gestures to researchers and learners. Child Development, 71, 231–239.

- Gopnik, A., & Meltzoff, A. N. (1997). Words, thoughts, and theories. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gopnik, A., Meltzoff, A., & Kuhl, P. (1999). The scientist in the crib. New York: HarperCollins.

- Gottlieb, G. (1992). Individual development and evolution: The genesis of novel behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Green, D., Ford, M., & Flamer, G. (Eds.). (1971). Measurement and Piaget. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Greenfield, P. (2001). Culture and universals: Integrating social and cognitive development. In L. Nucci, G. Saxe, & E. Turiel (Eds.), Culture, thought, and development (pp. 231–277). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Inhelder, B., & Chipman, H. (Eds.). (1976). Piaget and his school. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Inhelder, B., de Caprona, D., & Cornu-Wells, A. (Eds.). (1987). Piaget today. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Johnson, M. (1998). The neural basis of cognitive development. In W. Damon (Series Ed.), D. Kuhn, & R. Siegler (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 2. Cognition, perception, and language (5th ed., pp. 1–49). New York: Wiley.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A., & Inhelder, B. (1975). If you want to get ahead, get a theory. Cognition, 3, 195–212.

- Keil, F. (1984). Mechanisms in cognitive development and the structures of knowledge. In R. Sternberg, (Ed.), Mechanisms of cognitive development (pp. 81–100). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Keil, F. (1989). Concepts, kinds, and cognitive development. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kessen, W. (1965). The child. New York: Wiley.

- Kessen, W. (1984). Introduction: The end of the age of development. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Mechanisms of cognitive development (pp. 1–18). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Klahr, D. (1984). Transition processes in quantitative development. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Mechanisms of cognitive development (pp. 101–139). San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Kohlberg, L. (1973). The claim to moral adequacy of the highest stage of moral development. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 630–646.

- Langer, J. (1969). Theories of development. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

- Lerner, R. (1986). Concepts and theories of human development (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

- Lerner, R. (1998). Theories of human development: Contemporary perspectives. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (5th ed., pp. 1–24). New York: Wiley.

- Lewis, M. (2000). The promise of dynamic systems approaches for an integrated account of human development. Child Development, 71, 36–43.

- Liben, L. (1981). Individuals’ contributions to their own development during childhood: A Piagetian perspective. In R. M. Lerner & N. Busch-Rossnagel (Eds.), Individuals as producers of their development (pp. 117–153). New York: Academic Press.

- Loevinger, J. (1976). Measuring ego development. New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Milbrath, C. (1998). Patterns of artistic development in children. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, P. H. (1983). Theories of developmental psychology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Murray, F. (1972). The acquisition of conservation through social interaction. Developmental Psychology, 6, 1–6.

- Mussen, P. (Ed.). (1970). Carmichael’s manual of child psychology. New York: Wiley.

- Mussen, P. (Ed.). (1983). Handbook of child psychology (4th ed., Vol. IV). New York: Wiley.

- Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard, T., Boykin, A., Brody, N., Ceci, , Halpern, D., Loehlin, J., Perloff, R., Sternberg, R., & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns. American Psychologist, 51, 77–101.

- Norman, D. A. (1993). Cognition in the head and the world: An introduction to the special issue on situated action. Cognitive Science News, 17, 1–6.

- Overton, W. (1998). Developmental psychology: Philosophy, concepts, and methodology. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (pp. 107–188). New York: John Wiley.

- Oyama, S. (1985). The ontogeny of information: Developmental systemsandevolution.Cambridge,UK:CambridgeUniversityPress.

- Oyama, S. (1999). Locating development: Locating developmental systems. In E. Scholnick, K. Nelson, S. Gelman, & P. Miller (Eds.), Conceptual development: Piaget’s legacy (pp. 185–208). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Piaget, J. (1962). Comments on Vygotsky’s critical remarks. Preface. In L. Vygotsky, Thought and language (pp. 1–14). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Piaget, J. (1963). The origins of intelligence in children. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Piaget, J. (1967). Six psychological studies. New York: Random House.

- Piaget, J. (1970). Piaget’s theory. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Carmiachael’s manual of child psychology (pp. 703–732). New York: Wiley.

- Piaget, J. (1971a). Biology and knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Piaget, J. (1971b). The theory of stages in cognitive development. In D. Green, M. Ford, & G. Flamer (Eds.), Measurement and Piaget (pp. 1–11). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Human Development, 15, 1–12.

- Piaget, J. (1975). The development of thought: Equilibration of cognitive structures. New York: Viking Penguin.

- Piaget, J. (1977). Piaget on Piaget [Motion picture]. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. (Distributed by Yale University Media Design Studio, New Haven, CT, 06520).

- Piattelli-Palmarini, M. (Ed.). (1980). Language and learning: The debate between Jean Piaget and Noam Chomsky. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Plunkett, K., & Sinha, C. (1992). Connectionism and developmental theory.British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 10,209–254.

- Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rogoff, B., & Lave, J. (Eds.). (1984). Everyday cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rogoff, B., & Wertsch, J. (Eds.). (1984). Children’s thinking in the zone of proximal development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Saxe, G., Guberman, S., & Gearhart, M. (1987). Social processes in early number development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 52 (2, Serial No. 216).

- Scribner, S., & Cole, M. (1973). Cognitive consequences of formal and informal instruction. Science, 182 (35), 553–559.

- Shweder, R., & LeVine, R. (Eds.). (1984). Culture theory: Essays on mind, self, and emotion. New York: Cambridge University Press.