View sample Waterfront Planning Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Waterfront planning considers the future of the shoreline rivers, lakes or oceans, especially the redevelopment of abandoned port lands in urban areas.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Evolution Of The Port–City Interface

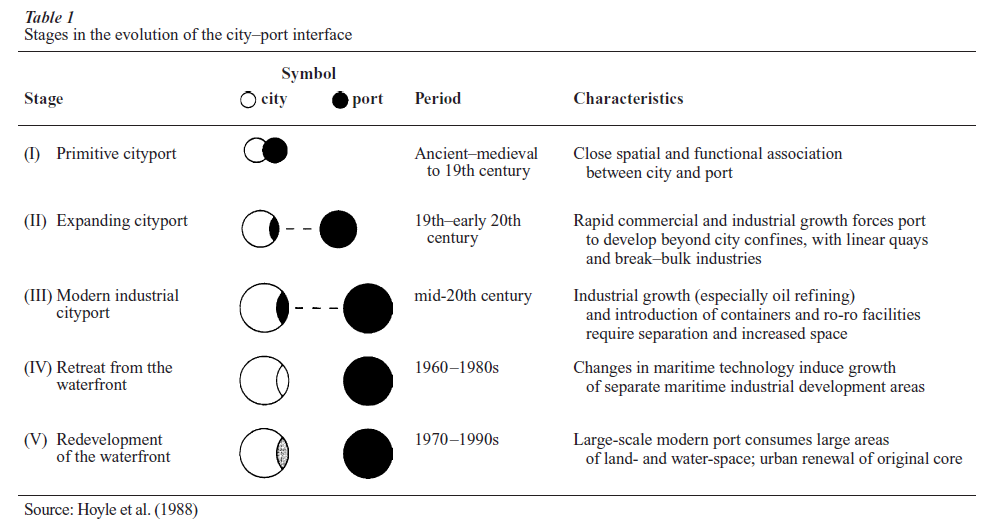

Waterfront redevelopment became a major planning activity in almost every port city in the 1970s and 1980s. Transport geographers such as Hoyle (1988) suggest that redevelopment is only the latest stage in the evaluation of the port–city interface (Table 1). The primitive city-port of the nineteenth century (Stage I) used medieval technology to unload sailing ships: nets, pulleys, and carts. Many ports were rebuilt in the late nineteenth century (Stage II) to accommodate steamships with warehouses, linear quays, and rail terminals. The Port of London Authority (1908) was an early public agency which consolidated privately-owned docks and built modern facilities. Its example was followed by other cities so that much of the urban waterfront in the mid-twentieth century was publicly owned, devoted to port industrial uses and not accessible to the general public.

The modern industrial cityport (Stage III) emerged quite quickly in the 1960s and 1970s due to powerful technological changes. Passenger terminals disappeared as jet aircraft replaced ocean liners. Fleets of small fishing boats were replaced by factory vessels. General freight switched to container ships. Huge bulk carriers and supertankers needed ocean terminals. Port-related industries in multistorey facilities departed for suburban sites with expressway access, or to other countries.

New port facilities required less labor, and more land. Container ports were approximately 40 times faster than conventional cargo facilities, using a fraction of the labor (Chilcote 1988), but needed 10 times the land for staging fast rail or highway access. Competition from new ex-urban port facilities was fierce (Stage IV). In a few years, Port Elizabeth, NJ replaced Manhattan, Oakland replaced San Francisco, Tilbury replaced London, and Boston and Philadelphia lost much of their cargo trade. By 1980, almost every maritime city had underutilized port lands available for redevelopment (Stage V) on the front doorstep of its central business district (CBD). The largest ports had enormous derelict areas; London had over 5000 acres available in 1980, in docks that had been the busiest in the world only 20 years before. Whole communities of dock workers became unemployed.

2. Opportunities And Problems For Waterfront Planning

The good news was that the abandoned port lands were in large, publicly-owned blocks close to the CBD of many cities. Most waterfront sites did not need expropriation of private property or displacement of residents, common problems in previous urban renewal projects. The waterfront became available during a period when many cities were looking for lands to expand the financial and service industries in their CBD. Best of all, waterfront sites have a strong sense of place, with long views, milder microclimates and opportunities for long, uninterrupted walks that one rarely finds elsewhere in most cities.

Waterfront planners faced enormous difficulties in redeveloping these sites. The port authorities and railways withheld their lands and interjurisdictional conflicts impeded planning. Conflicting demands for economic development, parks, and jobs increased political difficulties. The sites were often polluted and encumbered with industrial structures like grain elevators, which have heritage value but are difficult to reuse. Port lands had inadequate local utilities and were often cut off from the CBD by expressways and railway lines, requiring large early infrastructure investments.

3. Waterfront Planning Practice

While most nineteenth century cities considered their waterfronts as industrial districts to be exploited for maximum economic development, some shoreline was improved for public uses. The 1909 Plan of Chicago was a leader in this approach, reserving the entire shoreline of Lake Michigan for public parks. Gracious waterfront parks and promenades were sometimes added during infrastructure projects, using fill to extend the land adjacent to the downtown. New York’s Battery Park, London’s Victoria and Albert Embankments, and the Seine esplanade in Paris were welcome improvements. Waterfront projects by F. L. Olmsted, especially the Charles Muddy River improvements in Boston, would prove influential as a result of their natural systems approach.

New planning techniques evolved for 1970s waterfront redevelopment projects. Most projects were implemented by a redevelopment authority, although the level of government which controlled the agency depended upon who was willing to make the early infrastructure grants. Good implementation practice required these agencies to manage three areas: politics, finance, and urban design.

3.1 Politics

Excellent long-term political management is required for waterfront redevelopment except in rare cases such as the Barcelona Olympics or Lisbon World’s Fair, where deadlines and national pride pushed the projects forward in record time. Most urban waterfronts take decades to rebuild because the sites are large and complex. It often took five to ten years to build the development coalition needed to have a plan approved. Good relations with local governments was an advantage, since they often controlled infrastructure needed for redevelopment. Unilateral action by a senior government often led to long-term delays.

Good political management included:

(a) good relations and no surprises for sponsoring governments,

(b) board of directors well connected to all levels of governments,

(c) strong links to local government at staff and board levels,

(d) good relations with local residents, and

(e) linking private development with public benefits, especially waterfront parks.

3.2 Finance

Waterfront redevelopment requires start-up capital investment for land assembly, site clearance, environmental remediation and infrastructure. These costs make the projects unattractive to the private sector, since it takes years before political consensus is reached and land is ready for building. Substantial government start-up grants were required for most waterfront projects in the 1970s, while many governments were reducing funds for urban redevelopment. Many agencies therefore pursued investment by developers using some form of public–private partnership. The agency could assemble and clear land, negotiate planning approvals and install infrastructure. Private developers were solicited to complete the project. Private investment started late, built slowly, and cycled with the local property market. Flagship projects, such as the World Financial Center (New York) or Canary Wharf (London) often did not arrive until an agency had demonstrated credibility with site improvements, small developments and changing the waterfront image. Big projects also waited for a positive point in the real estate cycle, or risked bankruptcy like Canary Wharf.

Good financial planning practice included:

(a) access to long-term funding for infrastructure,

(b) streamlined developer selection process,

(c) incorporating recessions into financial plans,

and

(d) some infrastructure and social housing projects waiting for recessions.

New York’s Battery Park City Authority set a good example in the use of bonds to finance capital investment.

3.3 Urban Design

The most important element of waterfront urban design is to provide continuous, public access to the water’s edge. A high-quality pedestrian promenade along the shoreline is appreciated by the public and adds value to adjacent property. Political controversies erupted in London and Boston when developers seized ownership of the water’s edge, while the Toronto agency was dismantled after delays in delivering waterfront parks.

Urban design for waterfront redevelopment should facilitate over, several decades, implementation of:

(a) small development increments,

(b) tight phasing plans,

(c) simple infrastructure that can be phased,

(d) adapt existing infrastructure and buildings,

(e) continuous public access to the water’s edge,

(f ) view corridors down streets to the water.

Comprehensive schemes designed by one architect were discredited by early urban renewal projects. The 1979 plan for Battery Park City in New York was influential for its approach and urban design guide-lines. The plan’s extension of the Manhattan street grid allowed flexibility, easy phasing, small increments and simple infrastructure. The agency’s commitment to creating quality public space before development made it a leader in urban waterfront design.

The waterfront redevelopment agencies learned from each other as they developed a new planning model. Baltimore, Boston, and Toronto were influential in the 1970s; the first two for festival marketplaces developed by the Rouse Corporation, and the latter for public programming facilities in recycled industrial buildings. These ideas were quickly copied around the world. A waterfront formula emerged: a festival marketplace, an aquarium, office buildings, condominium apartments for young urban professionals and perhaps a hotel. Like most formulae for planning, it did not replicate well in other countries and cultures, leading to poststructuralist criticism of global corporations overwhelming the local population while pro-viding few benefits for the displaced industrial workers (Harvey 1989).

The best waterfront planning pays close attention to a local sense of place and waterfront-related uses (Breen and Rigby 1994, 1996). While an authentic place is hard to define, plans which renovate buildings, keep waterfront uses (fishing fleets and marinas), and provide walkways and parks seem to be the most successful. Vancouver’s Granville Island demonstrated adaptive reuse of modern industrial buildings, while London’s Hays Galleria and Venice’s Arsenal renovated historic warehouses. At a regional scale, the best waterfront planning uses ecosystem principles to preserve shoreline environmental integrity, while providing public access and trails.

Completing redevelopment of big sites like the London Dockland may take 20 years. Meanwhile, a new generation of waterfront sites is emerging. Large waterfront railway yards, such as San Francisco’s Mission Bay, New York’s Riverside South and Vancouver’s False Creek may offer a different planning challenge. Since these lands are typically owned and developed by large private companies, planning initiative is falling more to the private sector than did the 1980s public–private partnerships. While these new developers may require less public subsidy, it remains to be seen whether public benefits such as affordable housing and open space can be secured from this new generation of waterfront redevelopment.

Bibliography:

- Breen A, Rigby D 1994 Urban Waterfronts: Cities Reclaim Their Edge. McGraw Hill, New York

- Breen A, Rigby D 1996 The New Waterfront: A Worldwide Urban Success Story. McGraw Hill, New York

- Bruttomesso R 1993 Waterfronts: A New Frontier for Cities on Water. International Centre Cities on Water, Venice

- Chilcote P 1988 The containerization story. In: Hershman M (ed.) Urban Ports and Harbor Management. Taylor and Francis, New York

- Gordon D 1997 Battery Park City: Politics and Planning on the New York Waterfront. Gordon and Breach, New York

- Hall P 1991 Waterfronts: A New Urban Frontier. University of California Institute of Urban and Regional Development, Berkeley, CA

- Harvey D 1989 The Condition of Post-Modernity. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD

- Hoyle B, Pinder D, Hussain M 1988 Revitalising the Waterfront: International Dimensions of Dockland Development. Bellhaven, London

- Wrenn D 1983 Urban Waterfront Development. Urban Land Institute, Washington, DC