View sample Urban Policy in Europe Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Introduction

The first question to be addressed here is: is there such a thing as a European urban policy? There is clearly a wide variety of urban policies in the different countries of Europe, so many that it is beyond the scope of this entry to review them all in any insightful way. It is also true that there are a number of European urban policies, in the sense of policies of the European Union that address urban problems. During the 1990s there have been significant moves towards the establishment of a European Urban Policy although it is not yet possible to say that this has been achieved in a comprehensive manner. It is possible, however, to identify the emergence of certain common policy themes and priorities.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The unifying theme of this entry, therefore, is the emergence of a European Urban Policy during the 1990s, the establishment of urban policy instruments in early 2000, and the broad policy objectives that this is designed to achieve. This is related to the broadly parallel development of European spatial policy over the same period, the focus of which will in the early years of the current century be on the development of a balanced and polycentric city system and the forging of a new rural-urban relationship.

The concept of a European policy is applicable specifically to the European Union (EU), which is a jurisdiction whose laws are superior to those of the 15 member states. Of course the EU does not include the whole of Europe but it does cover a sufficiently large number of member states to be representative, particularly taking into consideration the association agreements with certain Western non-members and the expectation that 11 countries in Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe will join and adopt the same policies by 2005–2010.

This entry will begin by discussing the dimensions and variety of urban policies and cultures to be found in Europe and the extent to which certain overall policy objectives are generally accepted. It will then go on to outline the development of urban policy in the 1990s and the state that policy development has reached at the time of writing. The place of urban policy within the wider structure of the EU and of related policy sectors, and the extent to which a European policy community can be identified is then explored. Finally some directions in which policy development may be expected in the next few years are indicated.

2. Common Themes Within Urban Policy In Europe

Although the urban form and cultures vary greatly between different parts of Europe (Newman and Thornley 1996), there are a number of policy themes that can be discerned very widely, if not universally. It is the exception in Europe for cities to be still growing in the traditional manner as a result of migration from surrounding rural areas. This was the dominant form of urban population growth in the nineteenth century in countries that industrialized early (e.g., Britain, Germany, and Belgium) and in much of the twentieth century in most of Southern Europe. Urban change in the last quarter of the twentieth century was often associated with factors such as migration into Europe of ethnic minority populations from former colonies, economic restructuring and the loss of large numbers of traditional manufacturing jobs, extensive suburbanization, longer distance commuting, and new home–work relationships. Many cities are, of course, attracting substantial population growth. This is especially true of those with the most favorable economic structure or position within Europe’s territory. A major concern in recent years has been the extent to which growth is concentrated in cities in the core of Western Europe, the so called ‘blue banana’ or ‘pentagon’ (CSD 1999). Many other cities are experiencing growth in the number of households and of the area of urbanized land associated with them without experiencing overall population growth.

National urban policies were widely adopted to address the social and economic consequences of migration, unemployment, and poverty and to promote urban economic development and regeneration. This period of urban policy was also characterized by considerable growth in acceptance of the idea of competition between cities. Several cities that were undergoing economic and social decline adopted policies of image promotion as a significant element in their regeneration strategy. Competition could take different forms. At times it was directed at potential visitors or inward investors for whom a very positive and attractive image was essential. At other times, the competition took the form of seeking to qualify for some form of assistance under national or European policy, for which it was necessary to assert a degree of need greater than that of the competition.

Concern for the urban environment has grown dramatically in the same period. One aspect of this relates to the growth in the use of private car transport and policy towards the construction of urban motorways. Growth in car ownership has been a universal phenomenon in Europe as elsewhere but the 1980s and 1990s have seen significant growth in investment in rail-based urban transit systems and in acceptability of policies to restrain or even prevent the use of cars in urban centres. This latter dimension shows very distinct North–South variations. The Nordic countries accept a very high level of restriction on the use of cars in urban areas while in more Southern countries, such policies are politically very difficult to introduce. Nevertheless several major cities including Athens, Paris, and Rome have suffered such extremes of atmospheric pollution that they have experimented with no-car days and other means of restricting car access.

Cities in the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe present a distinct set of urban policy issues. Their existing urban structure is often heavily influenced by the experience of central planning and the lack of any urban land market. Substantial investment and transformation has occurred during the 1990s but, in the context of European urban policy, they will continue to present a distinct set of issues for some years to come, especially in the context of the enlargement of the EU.

A number of identifiable policy themes are widely adopted throughout Europe or are being promoted specifically as European policies. These include policies for urban regeneration, directing development on brownfield, rather than greenfield, locations, urban economic development, property-led development, policies to combat social exclusion and the problems of peripheral social housing estates, policies to accommodate the growth in household numbers without population growth due to the greater number of one and two person households, policies to counteract urban sprawl and promote the concept of the compact city, and policies to minimize private car commuting and promote the use of energy efficient transit systems. Core–periphery issues are recognized at the European level as well as within several member states and the concept of a balanced and polycentric urban structure has been developed as a central objective of European spatial policy to counteract this.

3. The Place Of An Urban Policy In The EU

Since the EU originated as an economic community, it is by no means generally accepted that it should play a role in urban policy. Constitutionally, the EU cannot engage in activities for which there is no provision made in the founding treaties, i.e., for which there is no legal competence. Strictly speaking, this limits the scope of EU legislation but is not so restrictive in respect of funding and networking programmes and policy advocacy. In practice, the European Commission, as the main policy-making institution, regularly pushes beyond the strict limits of existing competences, often in anticipation of future treaty revisions. The latest revision, the Treaty of Amsterdam, entered into force in May 1999 (SO 1997).

Many aspects of urban policy have been introduced within the framework of programs for which a treaty basis previously existed, such as regional and environment policies, which are specifically intended to address urban problems although they may not be labelled urban policy. During the 1990s, there was growing political support for the idea that an urban policy should be added to EU competence as part of one of the periodic revisions of the treaties. The overall basis for this is the argument that over 80 percent of Europe’s population is urban, and that there is no specific channelling of funding in this direction although a substantial proportion of EU funding is directed at agriculture.

To date the objective of adding an urban title to the treaties has not been achieved. The latest revision, the Treaty of Amsterdam, amended the statement of overall duties and objectives of the Union by including inter alia, the phrases ‘to achieve balanced and sustainable development … strengthening of economic and social cohesion,’ and ‘promoting social and territorial cohesion’ (Articles 2 and 7D, Treaty of Amsterdam). These indirectly provide a treaty basis for urban policy, which can be conceived as policies to promote social cohesion. It is a common feature of EU policy development that significant policy initiatives take place before any explicit treaty competence is agreed by the member states. This was true of both regional and environment policies, both now and well established with a clear treaty basis, and it is reasonable to expect that the same trajectory is being followed by urban policy. Meanwhile it is possible to identify several distinct elements of urban policy derived from existing EU policy sectors.

4. The Evolution Of EU Urban Policy

European urban policy took distinct shape during the 1990s but the foundations in respect of both research studies and innovative policy initiatives were laid during the 1980s. Studies were undertaken into urban problems and into the comparability of urban data from different member states. One of the most meticulous attempts at overcoming data comparability problems and arriving at a consistent analysis was that undertaken by Cheshire and Hay (1989) who developed a concept of the functional urban region for which data was adjusted to eliminate the distorting effects of different administrative boundaries and definitions. Policy initiative during the 1980s included development of the concept of urban black spots, designed to focus the attention of the regional and social funds (European Social Fund [ESF] and the European Regional Development Fund [ERDF]), on what were essentially inner city problems. Up to this time, it was not considered appropriate for EU policy to focus on spatial designations below the regional level. However, the widespread recognition of inner city problems led to political pressure to incorporate policy measures within the structural funds that could address them.

Another element of urban policy thinking that came to the fore by the late 1980s was concern for the urban environment. This moved to the top of the political agenda following the 1989 European Parliament elections where a historically high vote for green parties was recorded in a number of member states and a significant if small green party group was elected.

4.1 Structural Funds

Before discussing the outcome of these initiatives, it may be helpful to explain the term structural funds. This term came in to use during the 1980s to refer to three major funding programmes, ESF, ERDF, and the guidance section of the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF). The latter, part of the Common Agricultural Policy, is not of further concern here. ESF and ERDF, on the other hand, are very important in the context of European urban policy. The ESF is not a social fund in the welfare sense, but in the sense of providing for the so-called social partners, i.e., employers and those employed. It is a fund designed to promote and steer employment policy. During the 1980s, reforms of the ESF allowed it to focus very directly on the type of job creation and wage subsidy schemes that were being developed in the UK and some other member states as an integral part of inner city policy. The ERDF originated in the 1970s as an augmentation to national regional policies and it was only during the 1980s that it began to operate according to policy objectives set at the European level (Williams 1996).

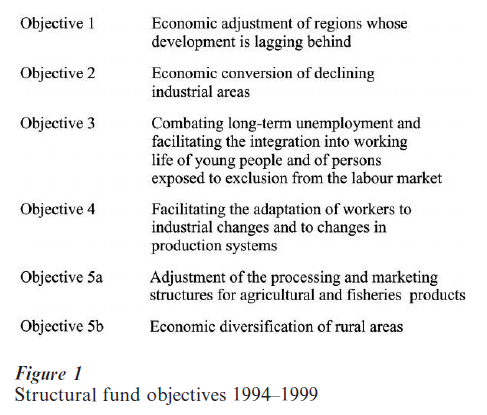

During the later 1980s agreement was reached on the coordination of the structural funds. This came into operation in 1989. In simple terms, the basis on which it operated was that five overall objectives were set (see Fig. 1). In the case of those with a primarily regional or spatial purpose, the area of benefit was designated. Thus the poorest areas, broadly speaking those with under 75 percent of the EU average per capita GDP, were designated Objective 1 areas and received maximum funding. Objective 2, which focused on areas undergoing industrial restructuring, was also subject to territorial designation and substantial funding. The majority of urban areas suffering economic or social problems were to be found within Objective 1 or Objective 2 areas. There were exceptions, generally whenever poor districts occur within economically successful city regions, such as Hamburg, the assumption being that the necessary resources were available locally.

4.2 Urban Environment

Building upon these foundations, the first major initiative of the 1990s was in respect of the urban environment. This was the preparation of the ‘Green Paper on the Urban Environment’ (CEC 1990), known as the Green Book, by the environment directorate of the Commission. This attempted firstly to establish the place of the city in European culture and to argue in a continent where approximately 80 percent of the population lives in urban or sub-urban areas, the quality of urban life and cultural identity are crucially dependent on the quality of the urban environment. More specific urban policy themes were developed, including the link between urban social cohesion and rural poverty as a result of rural–urban migration, the connection between urban development and air pollution, concern for conservation of the cultural heritage and the need to introduce traffic calming, to counteract pressures of urban sprawl and unrestricted tourist development. The Green Book went on to develop more specific policy proposals that could be implemented within the framework of EU powers as they then existed, particularly in respect of urban transport and planning, energy management, manage men to fur ban waste, promotion no industry, and heritage conservation.

The Green Book did not lead directly to the development of a European urban policy although it did capture the imagination of many urban planners and have an influence on policy thinking during the following years. One specific outcome was the establishment of the European Academy for the Urban Environment in Berlin (Williams 1996, pp. 204–10). Another was the adoption in 1994 of the Charter of European Sustainable Cities and Towns, whose signatories pledged themselves to work towards sustainable urban development, and establishment of the Car Free Cities Club, whose members were cities prepared to make a political commitment to the promotion of traffic reduction policies and the exchange of experience.

4.3 Urban Pilot Projects

Within the ERDF, provision is made for innovative or pilot projects and for community initiatives, funding programs targeted at specific problems often of an urban policy nature. An important step forward in the development of urban policy was the program of Urban Pilot Projects. This was a series of projects designed to test out new ideas for the delivery of urban policy. The intention of this program was to identify new policy measures and demonstrate the potential they had, not only in the context in which they were developed, but also in respect of transferability to cities in other parts of Europe. Projects were grouped around four major themes:

(a) economic development projects in areas with social problems, such as peripheral and some inner city residential areas with high unemployment levels and limited access to skills and training,

(b) areas where environmental actions can be linked to economic goals,

(c) projects for the revitalization of historic centres to restore economic and commercial activity,

(d) exploitation of the technological assets of cities.

As this was a pilot program, normally only two or three cities in each member state were designated for assistance.

A key feature of the Urban Pilot Programme was the requirement to publicize and disseminate the experience of each participating city. Many conferences and exhibitions were held with this in mind, but it is nevertheless very difficult to identify the extent to which lessons were transferred and applied to nonparticipating cities with comparable problems. An evaluation of the whole program was carried out in order to identify good practice and inform the development of a more substantial program known as URBAN, funded as a community initiative of the ERDF.

4.4 URBAN Community Initiative

URBAN was launched in 1994, before the pilot projects had finished or been evaluated, as part of the 1994–1999 agreement on the structural funds. This is perhaps an indication of the strength of the political coalition between the Commission and city authorities supporting greater intervention at the urban scale. It was designed to overcome serious urban social problems by supporting schemes for economic and social regeneration, renewal of infrastructure, and environmental improvement. It supports schemes to overcome serious social problems in inner areas of designated cities of over 100,000 population through economic revitalization, job creation, renovation of infrastructure, and environmental improvement. This program had a substantial budget, two-thirds of which went to cities within Objective 1 regions, most of the rest going to Objective 2 areas. One subtext for both these initiatives was to support moves to add an urban competence to the EU treaties at the Amsterdam summit in 1997. Although this was not achieved, the new emphasis on tackling unemployment will have a strong urban dimension, and urban policy development is continuing within existing competences. At the 1998 Urban Forum (see Sect. 4.5), Commissioner Wulf-Mathies emphasized that urban policies would be ‘mainstreamed’ within the structural funds.

Individual projects normally run for four years, must have a demonstrative character and potential to offer lessons to other cities, and form part of a long-term strategy for urban regeneration. The original intention was to designate around 50 projects, for which a funding partnership between the European Commission and the national authorities was proposed. The pressure for designation from cities was such that a total of 85 projects were approved by January 1997, many of which did not actually start until August 1998 (CEC 1998a), so evaluation has not yet been possible. By the end of the decade, approximately 120 projects had been designated. URBAN has thus proved to be a very popular program, so much so that it was maintained in the post-2000 funding period, contrary to the wishes of the European Commission, due to very strong political support form local and regional politicians throughout Europe.

4.5 Urban Agenda And The Urban Forum

Although the European Commission had initiated these various components of a European urban policy, it was politically necessary for the Commission to proceed with great caution in respect of any suggestion that it was proposing a new role for itself, thus the title it gave to an official communication was ‘Towards an Urban Agenda’ (CEC 1997). The stated purpose of this document was therefore to assess the extent to which existing policies affected urban areas and to examine the possibility of bringing these together to form a more coherent body of urban policies. It was also designed to stimulate debate among the urban policy professionals and, to some extent, generate pressure on the Commission itself in the form of advocacy of a more coherent EU urban policy from this group. Stimulating pressure from external lobbying groups in this way is not an unusual method of seeking to generate momentum for a particular policy direction. The focus of this pressure was twofold: firstly, to seek to influence governments participating in the discussions concerning the proposed amendments to the European treaties in preparation for the Treaty of Amsterdam; secondly, to contribute to preparations for the Urban Forum in 1998.

There was considerable pressure, especially from political representatives of major cities and urban policy experts, to add a so-called Urban Title to the European treaties in the Treaty of Amsterdam. In the event, this proved unsuccessful in that no Urban Title was incorporated in the Treaty, although the lobby did achieve some indirect success. The phrase ‘territorial and social cohesion’ was added to the section dealing with overall objectives and duties (Article 7D). This phrase can be taken to refer to the need for coherent spatial and urban social policies. Additionally, the Amsterdam Treaty added an Employment Title, which also provided a basis for intervening in issues of urban economic development and social exclusion.

The Urban Forum was an event held on the initiative of the then Commissioner, Dr. Monika Wulf-Mathies, in Vienna in November 1998. This meeting was attended by over 800 representatives of major cities and urban policy professionals at which a major document outlining the direction in which European Urban policy might go was launched. This was entitled Sustainable Urban Development in the European Union: A Framework for Action (CEC 1998b). This document aimed to create the foundation for a more highly developed and targeted European urban policy. The first part set out the general principles, political context, and rationale for the policy, noting also the applicability of the principal of subsidiarity. The key policy development takes the form of a set of 24 Actions grouped under four broad policy aims:

(a) strengthening economic prosperity and employment in towns and cities,

(b) promoting equality, social inclusion, and regeneration in urban areas,

(c) protecting and improving the urban environment: towards local and global sustainability,

(d) contributing to good urban governance and local empowerment (CEC 1998b, p. 11).

Some of the Actions propose the use of existing policy instruments to meet urban policy objectives more explicitly. For example, Action 8 makes proposals for Structural Fund support for urban regeneration. In order to be implemented, it is necessary for the Structural Funds’ operational guidelines to incorporate similar principles and this is being negotiated where appropriate. Other Actions anticipated the new powers, especially in respect of social exclusion and employment promotion, available following ratification of the Treaty of Amsterdam. Certain Actions are directed towards matters within the responsibility of urban authorities, for example, Action 11 on implementation of existing environmental legislation, while others seek to apply to the urban context international agreements, such as the Kyoto strategy on climate change.

5. The Urban Dimension Of European Spatial Policy

The policy framework for the network of cities and urbanized areas in Europe is not to be found in the urban policy instruments discussed above. Instead it is to be found within the framework of European spatial policy. Spatial policy has been developed over a similar period, reaching a degree of coherence with the adoption of the European Spatial Development Perspective in 1999 (CSD 1999, Williams 1999, 2000). Although this is better understood as a separate field of policy development, concerned with the territorial cohesion of urban and rural areas, it does incorporate certain guiding principles which provide a framework for urban development.

The ESDP was based on certain principles by the ministers responsible for spatial planning in 1994: development of a balanced and polycentric urban system and a new urban rural relationship; securing parity of access to infrastructure and knowledge; sustainable development, prudent management and protection of nature, and cultural heritage. These principles have no mandatory effect: there is no European spatial plan that must be adhered to. However, these are intended to provide a framework for policy thinking at national, regional, and local levels.

In several member states, most notably France and the UK, the national urban system is dominated by one primate city (Paris and London), and in some others, such as Spain and Italy, two cities jointly dominate the urban structure (Madrid and Barcelona, Rome and Milan). There were fears that, at the European level, a similar situation may come about especially after the creation of the single market in 1992. More specifically the fear was that a core region of Western Europe, from London through Brussels and Amsterdam, including Bonn and Frankfurt and ending with the Milan region of Italy, would become so intensely developed and become so dominant both politically and economically that it would unbalance the overall spatial structure of Europe and consign cities and regions in the periphery to a perpetual state of relative underdevelopment. An influential French study into the spatial structure of Europe gave the term ‘Blue Banana’ to this core region (Brunet 1989), and the image remains in use.

The principal exception among the major member states to this core–periphery model of urban development was Germany. The pre-1990 German Federal Republic was an especially good example of a polycentric urban structure. Several cities had major national or international functions (e.g., Frankfurt and Bonn) or were internationally significant commercial centres (e.g., Hamburg, Dusseldorf, and Munich). This was perceived to be a more appropriate model for application at the continental scale, and has been incorporated in EU spatial policy as a guiding principle.

6. The State Of EU Urban Policy Development In 2000

In 2001, EU policy towards cities and urbanized areas can, for the most part, be found in two particular bodies of policy-making. One is the funding program for urban projects and initiatives designed to combat social exclusion, the other is the spatial policy framework for the network of cities and city regions. Policies directed at urban areas can of course also be found within the context of energy, transport, and environment policies, for instance in respect of pilot schemes for energy-efficient transit systems and policies for landfill and waste disposal.

At the Urban Forum in 1998, the Commissioner was advocating that urban policies and their associated funding should be ‘mainstreamed’ within the overall structural funding program when this was renewed for the funding period 2000–2006. The intention was that cities would not be regarded as dependent upon one relatively small fund for any special initiatives. In fact this proposal was strongly opposed by the representatives of the cities, and it proved necessary to propose the continuation of a dedicated funding program, known as URBAN, in order to satisfy these objections. This is one of only four Community Instruments, compared with 14 in the earlier funding period and is substantially better funded than its predecessor. It is not possible at the time of writing to comment on what this program may achieve, since the guidelines have only recently been negotiated and have not yet received final approval.

The spatial policy framework is now established in the form of the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP), adopted by the Ministers at Potsdam in May 1999. Although this is in no sense a legally binding policy statement, it is anticipated that it will form significant guidance for urban development, especially in respect of networks of cities and links between them, and in respect of the need to minimize urban sprawl and maximize sustainability through compact urban development and efficient transit systems. An action program to follow up the ESDP was agreed in October 1999, which included further study programs designed to develop and operationalize concepts such as a balanced polycentric urban structure.

7. Urban Networking And The Development Of A Policy Community

A noteworthy feature of urban policy-making during the 1990s has been the extent to which cities have attached importance to networking activities. The term ‘policy community’ is sometimes applied to the entire group of people and organizations that play a role in any given sector of policy-making. This is readily recognizable phenomenon within the national context. What is new is the extent to which it is becoming possible to identify a European policy community in a number of sectors including urban policy.

The European Commission has sought to stimulate networking and partnership activities through a number of programmes requiring participant cities to form partnerships with cities in other member states in order to qualify for funding. Some partnerships were fairly short-lived but several small networks were established which have since grown into quite substantial organizations. One of the most significant is a body called ‘Eurocities,’ whose members are all regional cities of over 250,000 population. The original core group was formed by certain ‘second cities,’ Birmingham, Barcelona, Lyons, and Frankfurt, which were seeking to support each other in their efforts to achieve a higher European profile, outside the shadow of their respective national capitals. Eurocities has members from throughout the EU, and now includes capital cities. It is the major non-government organization currently active in the field of European urban policy and has a wide range of working parties concerned with different policy sectors—urban environment, transit systems, telecommunications, economic development, social exclusion, etc.—which not only react to proposals and consultations from the Commission but also prepare and submit their own policy proposals. The URBAN Community Instrument is itself to some extent the product of this process. Eurocities has also been instrumental in promoting its own specific networks, for example the Car Free Cities Club, a network of cities that have committed themselves to implement measures to reduce the impact of cars in city centers.

There are a number of other networks representing smaller cities, or cities with particular functions or situations, such as historic cities that have difficulty reconciling heritage conservation and tourism pressure, or cities sharing a particular manufacturing industry.

8. New Policy Concepts And Agendas

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, very substantial progress has been made, compared with the situation a decade earlier, in developing a coherent body of European urban policy. The principle that the EU should contribute substantially to meeting urban policy objectives is now accepted and for urban policymakers in city administrations, this is a major factor in their daily professional lives. On the other hand, the ambitions of several of those who were actively seeking the incorporation of urban policy within EU competences have by no means been fulfilled. There is still no Urban Title in the treaties, and therefore there are only weak powers to legislate, and only on the basis of unanimous political support.

The present situation is not likely to remain static. The spatial policy aspect is continuing to evolve, associated with study programs which will seek to develop policy instruments to promote a polycentric urban structure and more integrated urban–rural relationships. It is anticipated that the link between the European Spatial Development Perspective and the Structural Funds will be made explicit for the 2006 revision of the Funds. Urban environment and transport initiatives can be expected to continue, with strong political support especially from Northern Europe. It was always envisaged that the Urban Forum should become a regular event. Although this has not yet happened, it would be inconceivable for this not to happen, given the political strength of the cities of the EU. Finally, the next round of enlargement of the EU, to incorporate former communist countries of Central Europe, will take place during the period 2005–2010. The impact of this is yet to be fully appreciated among existing EU members, in spite of many studies and technical assistance programs that have taken place. However, the urban regeneration and social cohesion problems that these will bring will have a more profound influence than anything hitherto experienced on the future development of EU urban policy.

Bibliography:

- Brunet R 1989 Les villes europeennes, La Documentation francais. RECLUS, DATAR, Paris

- CEC 1997 Towards an Urban Agenda, COM (97) 197 final, Brussels, Belgium

- CEC 1998a URBAN Community Initiative Summary Descriptions of Operational Programmes, Directorate-General for Regional Policy and Cohesion, Brussels, Belgium

- CEC 1998b Sustainable Urban Development in the European Union: A Framework for Action, Directorate-General for Regional Policy and Cohesion, Brussels, Belgium

- Cheshire P, Hay D 1989 Urban Problems in Western Europe. Unwin Hyman, London

- CSD 1999 European Spatial Development Perspective, Committee of Spatial Development, Potsdam, Germany

- Newman P, Thornley A 1996 Urban Planning in Europe. Routledge, London

- SO 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam, The Stationary Office, Cm 3780, London

- Williams R H 1996 European Union Spatial Policy and Planning. Paul Chapman Publishing, London

- Williams R H 1999 Constructing the ESDP–Consensus without a Competence. Regional Studies 33(8): 793–7

- Williams R H 2000 Constructing the European Spatial Development Perspective—For Whom? European Planning Studies (forthcoming)