View sample Transportation Planning Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing services team for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Planning for the movement of people, goods, and ideas about cities and regions requires a systems framework. This reflects the intimate, two-way relationship that exists between transportation facilities and the social, economic, and environmental quality and character of places that are served. It is in this broader, more inclusive context of transportation planning that the field finds itself in the midst of a paradigm shift.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. A Balanced Approach To Transportation Planning

Historically, transportation planning has been about ensuring efficiency in movement—that is, getting from point A to point B as quickly and as safely as possible. In the industrialized world, expansive overpasses and monumental expressways that criss-cross metropolitan areas stand as edifices of this philosophy. However, with time the cumulative impacts of planning for speedy, effortless movement, or for mobility, have revealed themselves—in some ways, positively, such as increased economic productivity and modernization, but in other ways, negatively, in the form of air pollution, worsening traffic congestion, wasteful sprawl, severance and degradation of neighborhoods, and isolation of people by class, race, and physical abilities. For this reason, some critics call for a more balanced, ecological approach to the field, one that accepts limits and acknowledges co-dependencies and connections (Ewing 1995). Other objectives besides mobility that need to enter the mix include accessibility, livability, and sustainability.

The risks of planning principally for mobility are underscored by US experiences. The United States averages 750 automobiles per 1,000 inhabitants, making it the world’s most automobile-dependent society. The nation’s economic prosperity is intimately tied to systems of highways, railways, and air transport that allow for efficient collection and distribution of people, raw materials, goods, and ideas. However, with under 5 percent of the world’s population, the United States consumes 25 percent of petroleum-based fossil fuels and produces a comparable share of all energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. Cities like Los Angeles and Denver suffer from some of the worst photochemical smog anywhere. As poor countries of Africa and Asia prosper and begin to mimic the vehicle ownership patterns of the United States and other industrialized nations, the world’s finite resource base and capacity to absorb the astronomical increases in greenhouse gases without adverse climate change, many fear, will be pressed to the limits.

1.1 Mobility Planning

Time is a much-valued, irretrievable resource, thus planning for speedy movement has always been, and will always be, central to transportation planning. The standard methodology for mobility-based planning is the four-step travel-demand forecasting model. This involves a series of sequential, independent mathematical steps which lead to bottom-line forecasts of future vehicle trips on major highways and transit lines in a metropolitan area. The programming and construction of capital improvements like new highways or rail-transit extensions are based on the outputs of this four-step model.

Step one, called ‘trip generation,’ estimates numbers of trips per household by purpose (e.g., to work, for shopping) based on factors like household size, income, and number of motor vehicles. Step two, called ‘trip distribution,’ projects the flows of estimated trips to competing destinations, whether employment centers, shopping plazas, entertainment venues, or elsewhere. Traditionally, a gravity model is used to distribute estimated trips spatially—for example, a shopping mall with a million square feet of floor space can be expected to draw twice as many trips as one with a half million square feet, adjusted for impedance effects of travel time or distance. The third step, called ‘modal split,’ divides forecasted travel flows, by purposes, among competing modes, like drive-alone car, carpool, public transit, or walking. Discrete choice models that estimate the likelihood of selecting a particular mode based on its service-price attributes and characteristics of the traveler (e.g., income) are normally used. The final step, called ‘traffic assignment,’ involves computerized loading of predicted flows by mode on planned highway and transit networks to evaluate performance, with performance defined mainly in terms of average speeds.

In recent years, transportation planners have sought to refine the four-step model in several ways. One is to represent the dynamic, synergistic relationship between transportation and urban settlements patterns—to reflect, for example, that while new growth generates traffic, as roadways start filling up, growth starts migrating elsewhere (Putman 1991). Another is to model household activities as opposed to vehicle trips. Called ‘activity-based micro-simulation,’ this approach uses nonlinear mathematical programming tools to simulate activity patterns across a metropolitan landscape and the vehicle trips as well as tailpipe emissions that will result. In the United States, the Los Alamos National Laboratory has developed a micro-simulation package, called TRANSIMS, that projects movement of individuals in Portland, Oregon second-by-second according to where future activities are most likely to be sited. The model aims to capture the many behavioral adjustments that are made to changing traffic conditions—e.g., when a trip takes too long, people seek out other routes, switch from car to bus, leave at different times, or opt to forego the trip altogether.

1.2 Accessibility Planning

An alternative to planning for movement is to plan for places by making them more accessible. This can be achieved by bringing origins and destinations (e.g., homes and workplaces) closer to one another or by increasing speeds on the channel ways that connect them. Accessibility planning embraces the notion that transportation is a secondary activity—it involves people going to places, be they places of work, of recreation, of worship, of retailing, etc. People do not consume transportation for its own sake, but rather for purposes of reaching oft-visited places. If anything, people want to minimize the time spent moving so that they can spend more time at desired destinations, rather than on the road. Focusing on accessibility as opposed to just mobility leads to a whole different set of planning strategies—for example, instead of laying more asphalt to expedite cars and trucks, mixed-use communities can be designed that reduce the spatial separation of activities. Many in-vogue land-use planning approaches, like jobs-housing balance, transit villages, and compact, neo-traditional development, are centrally about making cities and regions more accessible (see Calthorpe 1994, Bernick and Cervero 1997). The difference between planning for mobility versus accessibility is the difference between planning for cars versus planning for people and places.

So far, the Netherlands has made the most headway in reforming regional transportation planning to give equal emphasis to accessibility and mobility (Tolley and Turton 1995). Dutch planners draw mobility profiles for new businesses which define the amount and type of traffic likely to be generated. They also classify various locations within a city according to their accessibility levels. For example, sites that are well served by mass transit, that are connected to nearby neighborhoods by bike paths, and that feature mixes of retail shops receive high accessibility marks. Such locations are targeted for land uses that generate steady streams of traffic, such as college campuses, shopping plazas, and public offices. More remote areas that can be conveniently reached only by motorized means are assigned land uses that need not be easily accessible to the general public, like warehouses and factories. Thus, to make sure the ‘right businesses’ get the ‘right locations,’ Dutch planners see to it that the mobility profile of a new business matches with the accessibility profile of a neighborhood.

1.3 Planning For Sustainability And Livability

As a rapacious consumer of natural resources and emitter of pollutants, the transportation sector must also be judged on the basis of sustainability—maintaining or improving, as opposed to harming, the natural environment (see Newman and Kenworthy 1999). Sustainability argues for resource-efficient forms of mobility, such as metrorail systems that link planned urban centers in the case of big cities and dedicated carpool and bus lanes that reward efficient motor-vehicle use in smaller ones. Congestion pricing, parking restraints, and the development of alternative fuel vehicles are other strategies that embrace sustainability principles.

Livability applies principles of sustainable planning to the scale of the neighborhood. It is about the human need for social amenity, health, and well-being. Many European cities have brought livability to the forefront of transportation planning, opting for programs that tame and reduce dependencies on the private car (see Pucher and Lefevre 1996). Traffic calming is one such approach, pioneered by Dutch planners who have designed speed humps, realigned roads, necked down intersections, and planted trees and flowerpots in the middle of streets to slow down traffic. With traffic calming, the street is viewed as an extension of a neighborhood’s livable space—a place to walk, chat, and play. Automobile passage becomes secondary. After traffic calming its streets in the early 1990s, the city of Heidelberg, Germany witnessed a 31 percent reduction in accidents and a 44 percent reduction in casualties (Beatley 2000).

Car-sharing and car-limited communities have also gained popularity in European cities as ways of enhancing the quality of in-city living. Car-sharing relieves residents of the financial burden of owning one or more automobiles, allowing them instead to lease cars on an as-need basis through a cooperative arrangement. Car-share members can efficiently tailor car usage to specific purposes (e.g., small electric cars for in-neighborhood shopping and larger ones for weekend excursions). They also economize on travel by opting to move around by foot, bike, and mass transit more often. Presently, over 50,000 members share some 2,800 vehicles in 600-plus cities across Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Great Britain. More extreme is car-limited living, which is being actively promoted in parts of Amsterdam, Bremen, Germany, and Edinburgh, Scotland. In Amsterdam’s Westerpark district, only 110 permanent parking spaces are provided for residents of 600 housing units. The project has attracted a number of middle-class families with children who value living in a setting where space is used for common greens and play areas, rather than for parking cars.

2. Coming Challenges And Policy Responses

Many powerful mega-trends are working against the broader objectives of transportation planning— namely, in favor of increased automobile dependence and usage at the expense of concerns like accessibility, sustainability and livability. The postindustrial world has given rise to ‘travel complexity’—the trend toward irregular, less predictable work schedules, the geographic spreading of trips, and increased trip-chaining (e.g., linkage of trips, such as from work to the childcare center to the grocery store to home). All of these trends favor drive-alone, ‘auto-mobility.’ The share of trips by carpools and vanpools has fallen throughout US cities over the past two decades, despite the construction of dedicated high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes and aggressive rideshare promotion (Pisarski 1997). Ridesharing’s decline in metropolitan Washington, DC, traditionally one of America’s strongest vanpooling markets, is rooted in the shift from predominantly government to increasingly high technology employment; many of the region’s software engineers and Internet-industry workers keep irregular hours and rely on their cars during the midday break, making it nearly impossible to share a ride to work. The entry of women into America’s workforce, which soared from 26 million in 1980 to 63 million in 1997, has fueled trip-chaining—nearly twothirds of working women stop on the way home from work, often to pick-up children at day-care centers (Sarmiento 1998). Telecommunication advances continue to diminish the need for spatial proximity, hastening the pace of new growth on the edges of metropolitan areas and in far-flung rural townships. As growth continues to spread out, there is a widening mismatch between the geography of commuting (tangential and suburb-to-suburb) and the geometry of traditional transportation networks, which tend to be of a radial, hub-and-spoke design. Circuitous trip patterns and mounting traffic congestion, especially in the suburbs and exurbs, have resulted.

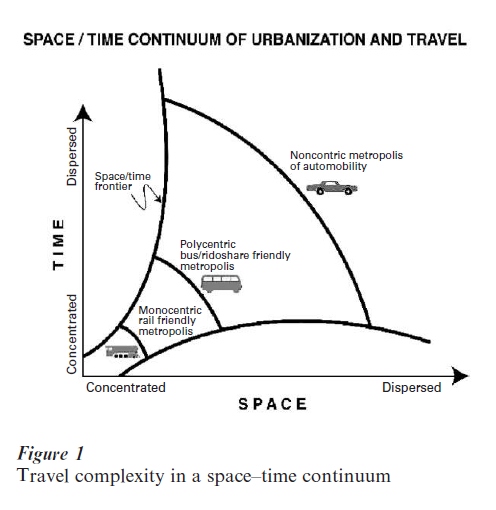

Collectively, evolving economic, demographic, and urbanization trends have formed new space-time arrangements, conspiring against all forms of movement except the private car. Figure 1 portrays this evolution along a space–time continuum. The traditional monocentric city with concentrated activities (e.g., downtowns and 8-to-5 work schedules) supported point-to-point rail services reasonably well. As technology advances gave rise to polycentric settlements and less regular time schedules, more flexible forms of collective-passenger transport, like bus transit and carpools, prospered. As cities and the regions of the future become increasing ‘noncentric’ and time schedules less certain and predictable, the frontier of space-time possibilities has expanded considerably. An immense challenge faced by the transportation planning profession is how to pursue the balanced agenda of mobility, accessibility, sustainability, and livability in light of these protracted, complicating trends.

2.1 Induced Demand

One of the most compelling reasons for more balanced, ecologically based transportation planning is the well-documented phenomenon of induced travel demand. Time and again, experiences show that building new roads or widening existing ones, especially in fast growing areas, provides only ephemeral relief—in short time, they are once again filled to capacity. A study using 18 years of data from 14 California metropolitan areas found every 10 percent increase in highway lane-miles was associated with a 9 percent increase in vehicle-miles-traveled four years after road expansion, controlling for other factors (Hansen and Huang 1997). Similar findings have been recorded in the United Kingdom (Goodwin 1996). In the United States, regional transportation plans, such as in the San Francisco Bay Area, have been legally contested by environmental interest groups on the very grounds that they failed to account for the induced travel demand effects of road investments and expansions.

Expanding road supply produces both near and long-term shifts. In the short run, expanded capacity prompts behavior shifts—people change modes, routes, and times-of-day of travel. For example, once a new road is opened, many who previously commuted on the shoulders of the peak shift to the heart of the peak. Over the longer term, structural adjustments occur, such as people and firms locating on parcels near interchanges to exploit the increases in accessibility provided by a new freeway.

The challenge of transportation planning is to create constructive channels for the induced shifts prompted by new transportation infrastructure. To encourage ‘green’ modes of transportation, like vanpools and shuttles, for instance, planners can set up HOV lanes along corridors which are the recipients of shifted trips. Time-of-day swings in trip-making can become more efficient by relaying real-time information on travel conditions and least-congested paths via Internet web sites and on-board navigational systems. Locational shifts can be of a more compact, mixed-use, walking-friendly form through zoning, tax policies, and other instruments that reward efficient and sustainable patterns of development.

2.2 Technology

Worldwide, billions of dollars are being spent on making roadways and cars smarter, under the guise of the Intelligent Transportation System (ITS). These initiatives seek to increase the efficiency of automobile movements many orders of magnitude, relying on the kind of technology and intelligence gathering once reserved for tactical warfare. In Great Britain, Germany, and France, over 200,000 motorists currently subscribe to Trafficmaster, a nationwide traveler information system. Infrared cameras located every six kilometers automatically record the license plates of passing vehicles and transmit the data via radio to a centralized data center. By matching license plates across different camera locations, a megacomputer calculates the average speed of travel for each roadway segment and relays the information in encrypted form to small receivers and visual displays mounted on the dashboards of subscribers’ cars. Alternative routes are suggested for avoiding traffic jams. One concern of making automobiles smarter is that travelers will flee buses and trains in droves. Mass transit must therefore also become smarter, through advanced technologies which optimize routing for door-to-door shuttles and which relay information on schedule-adherence to drivers and on expected times of arrival to waiting customers.

The one area where all sides agree that technology could yield important social, environmental, and economical benefits is by allowing for marginal-cost pricing, such as the collection of congestion tolls (Gomez-Ibanez 1999). This is happening in Singapore, where an electronic road pricing (ERP) scheme was introduced in 1998 (Cervero 1998). The system applies a sophisticated combination of radio frequency, optical detection, imaging, and smart card technologies. With ERP, a fee is automatically deducted from a store-valued smart card (inserted into an in-vehicle reader unit) when a vehicle crosses a sensor installed on overhead gantries at the entrances of potentially congested zones. The amount debited varies by time and place according to congestion levels. Cameras mounted on gantries snap pictures of violating vehicles to enforce the scheme. The system can identify a vehicle, deduct a charge, and capture a clear photo of its rear image at speeds up to 130 kilometers per hour. During its first year of implementation, traffic volumes declined by 15 percent on a major freeway along Singapore’s eastern shoreline, matched by comparable patronage increases along a parallel mass rapid transit (MRT) route.

Another promising direction for new technologies which supports sustainability and livability objectives is the modification of vehicle propulsion systems. Hybrid electric propulsion can boost energy efficiency by an estimated 30 to 50 percent by electronically recovering braking energy, temporarily storing it, and then reusing it for hill climbing and acceleration. Visionaries see a future of ultralight hybrid vehicles that combine the advantages of regenerative electronic braking with on-board fuel cells (Von Weisacker et al. 1997).

2.3 Institutional Reforms

Even with the most sophisticated technological breakthroughs, little progress can be made unless there is the institutional capacity to coordinate and implement new transportation programs and ideas successfully. Worldwide, transportation planning is mired by bureaucratic inertia and redundancies. In Bangkok, Thailand, for instance, more than thirty government agencies are responsible for the city’s transportation planning, management, and operations. Many economists promote privatization of public transportation as a means to cut costs and spur innovations, however even increased competition can backfire without a workable institutional arrangement. This is underscored by experiences in Rio de Janeiro, where more than 60 private bus companies serving the city have independent timetables and fare structures, penalizing many users who must transfer across bus routes.

Germany and Switzerland have formed regional federations for coordinating mass transit services, called verkehrsverbunden. Greater Munich’s federation, for example, functions as an umbrella organization for planning routes, services, and fares across the 5500-square-kilometer region’s many rail and bus service offerings (Cervero 1998). Besides coordinating schedules and timetables, the federation pools fare-box receipts and reallocates them to ensure socially equitable fares are charged while also rewarding individual operators for being productive and cost-effective.

Another noteworthy institutional reform in Europe has been the functional separation of roadbed ownership and maintenance (including highways and rail tracks), which remain in the public domain, from service delivery and which is open to public and private providers through competitive tendering (see Pucher and Lefevre 1996, Cervero 1998). Within the confines of standards set by government sponsors (e.g., regarding timetables, fares, and routing), the lowest-cost provider delivers the service. Thus, the public sector retains control over how services are configured, leaving it to market forces to determine at what price.

In the United States, the eyes of the transportation planning profession are on the state of Georgia, where an all-powerful regional transportation authority has recently been formed. Called the Georgia Regional Transportation Authority (GRTA), the organization not only oversees the planning and expenditure of funds for all urban transportation improvements in the state, but also has broad control over regionally important land uses, like shopping malls, industrial parks, and sport stadia. Local land-use decisions must conform to regional transportation and development goals, otherwise GRTA can effectively veto decisions by threatening to cut off all state infrastructure funds. GRTA’s formation was largely in reaction to decades of poorly planned growth in metropolitan Atlanta, matched by ever-worsening traffic congestion. The announced plan of a large high-technology employer to relocate out of Atlanta because of unsustainable traffic congestion and a declining quality of life was a political wake-up call. The region’s new planning philosophy—one of balancing urbanization and transportation investments—aims to enhance mobility while also placing the region on a pathway that promises a more sustainable and livable future.

Bibliography:

- Beatley T 2000 Green Urbanism: Learning from European Cities. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Bernick M, Cervero R 1997 Transit Villages in the 21st Century. McGraw-Hill, New York

- Calthorpe P 1994 The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream. Princeton Architectural Press, Princeton, NJ

- Cervero R 1998 The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Ewing R 1995 Measuring transportation performance. Transportation Quarterly 49: 91–104

- Gomez-Ibanez J 1999 Pricing. In: Gomez-Ibanez J, Tye W, Winston C (eds.) Essays in Transportation Economics and Policy. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC

- Goodwin P 1996 Evidence on induced demand. Transportation 23: 35–54

- Hansen M, Huang Y 1997 Road supply and traffic in urban areas: A panel study. Transportation Research 31: 205–18

- Newman P, Kenworthy J 1999 Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence. Island Press, Washington, DC

- Pisarski A 1997 Commuting in America II: The Second National Report on Commuting Patterns and Trends. Eno Transportation Foundation, Washington, DC

- Pucher J, Lefevre C 1996 The Urban Transport Crisis in Europe and North America. Macmillan Press, Houndmill, UK

- Putman S 1991 Integrated Urban Models 2. Pion, London

- Sarmiento S 1998 Household, Gender, and Travel. Federal Highway Administration. US Department of Transportation, Washington, DC

- Tolley R, Turton B 1995 Transport Systems, Policy and Planning: A Geographical Approach. Wiley, New York

- Von Weisacker E, Lovins A, Lovins L 1997 Factor Four: Doubling Wealth, Halving Resource Use. Earthscan Publications, London