View sample Time-Use Research Methods Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Why Study Time Allocation?

We all have 1440 min in our days. While we can buy goods, and the services of other people, we cannot directly purchase more minutes for ourselves. However, as we buy goods and services, and sell our own labor, we are trading our own time, and other people’s. Furthermore, our position in this market for time reflects aspects of our own past histories of time use—how much we spent in interaction with parents and siblings in our households of origin, time in schools and training, in various sorts of work and leisure activities. These past times accumulate, through the life course, to form that aspect of human capital that determines prospective earnings rates. Those whose hourly wage is greater than the average may wish to sell a relatively large part of their day as paid labor, since their earnings can, in effect, buy a still larger amount of time indirectly, as embodied in goods and services.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

So the apparently equally distributed resource is, paradoxically, both a source of and a fundamental expression of social differentiation. How we spent our time in the past provides the human capital that helps to determine our current time allocation, not just between work and leisure, but also, through mechanisms set out by Becker (1965) and Bourdieu (1985), amongst different sorts of leisure consumption. And employment-related human capital in turn effectively redistributes time: those below the average wage who have no financial capital must exchange each hour of their work for goods and services that embody on average less than an hour of the work of others, while those with high wages may exchange many hours of embodied labor for each hour of their work. Once we subtract paid work time from the day, and add back the time embodied in purchased goods and services, the poorest members of a society might have effective control over 15 hours each day and the richest 50 hours or more.

Yet despite this crucial role in the emergence of social structure, time allocation evidence does not at present form part of the core research material of any social science discipline. Why?

One contributing explanation is the paucity of good data. We have limited knowledge of our own time use. Like fish in water, we live in time; we are in it, but not aware of it. We are not well equipped to mark its passage or duration, and in any case the social scientist is interested not in time itself but in the particular activities to which successive periods are devoted. So if, for example, we ask survey respondents directly how much time they devote to a particular activity over a given period, the answers we get reflect little more than conventional expectations (‘I work 40 hours per week’ our respondent tells us, because her employment contract states this—but the actual hours worked are only accurately known if there is some externally imposed mechanism for registering this). For many categories of activity (housework, leisure activities, travel) respondents are unable to provide any straightforward answers at all (unless to report complete nonparticipation). There is no particular reason in the course of day-to-day living why we should know such an abstraction as the amount of time devoted to each element in a general classification of activities, so we cannot give good answers to researchers when they ask us about it.

2. Methodological Alternatives

There are four distinct approaches to the measurement of time use in a population: ‘stylized estimates’ as part of questionnaire inquiries, observational methods, the use of administrative records, and diary methods.

Despite the evident fact that people are unaware of their time allocation, much of what currently passes for scientific knowledge of time allocation nevertheless relies on direct questions to survey respondents. In particular, the standard models for the Labor Force Surveys collected by most developed countries routinely ask for estimates of amounts of time, on average, or over a typical week, or during the previous week, spent working in paid employment. Other surveys ask similarly about time devoted to, for example, child care and domestic chores. These produce ‘stylized estimate’ measures of time use.

This approach is certainly the simplest and cheapest way to collect information about how people use their time, but it has significant drawbacks. Research on the paid work time estimates deriving from this methodology suggests substantial and systematic biases (e.g., Robinson and Godbey 1997, pp. 58–9). Those who claim to work in excess of 40 hours per week progressively overstate the length of their work-week. The reason for this bias seems to be that as work time increases, it become more difficult to accommodate other necessary or desirable activities outside scheduled work times. These exceptional events within conventional work-start and -finish times are often forgotten, whereas exceptional events that lengthen the working week (e.g., overtime) are more likely to be remembered in the context of a question about work time. The longer the actual work week, the more likely it becomes that activities that might otherwise be located in ‘free’ time (e.g., medical visits, shopping, sports participation) are inserted during periods that the respondent normally expects to spend working, and the greater the proportional overestimate; hence the systematic bias.

Ethnographic research has often involved direct observation of people and the recording of their activities by the researchers. New technology now extends the role of direct observation, including such unobtrusive devices as individual location monitoring systems and closed-circuit or internet camera systems.

Observational methods have certain advantages, in that the researcher can ensure that respondents do not forget or suppress particular activities of interest. In the case of new technology, the option of reviewing tapes and videos can ensure accurate recording of people’s activities; ambiguities can be reassessed until a maximally precise determination can be reached. Such methods may be useful for analyzing small samples of special groups (residents of a retirement home or a small rural community) or activities in a specific location (such as the numbers of people who pass by a shop display and react or who engage in various activities in a town center).

On the other hand, direct observation studies are costly, they are in general labor intensive, and they may compromise personal privacy. Moreover, people can be expected to censor or distort their normal patterns when aware of continuous monitoring (the more so if they are conscious of an observer of differing nationality, class, sex, ethnicity, age group, or religion). However, continuous remote monitoring of medical conditions is gaining wide acceptability, and some extension of this, perhaps in conjunction with ‘beeper’ techniques (or, more formally, ‘experience sample methods’), in which respondents record current activities on random occasions during the day indicated by a ‘beep’ from a portable device, may grow in the future. But for the moment, for cost and other reasons, such approaches are not widely used.

Less direct observational methods, or ‘unobtrusive measures,’ include programs tracking the use made of computers at work and school (measuring the time people spend word processing, performing data analysis, checking e-mail, browsing the web, and so forth), telephone call and retail transaction records, and the like, recording what people do at particular times and in particular places.

Administrative records, some of which cover considerable periods of time, chiefly concern the official records of hours during which people are in engaged within institutions; most typically this involves employers’ records of work hours, but could in principle now involve any of those recreational facilities, hospitals, and prisons that use electronic methods to monitor individuals’ entries and exits. Administrative records typically provide large numbers of cases for analysis. However, they only cover the population which has contact with the institutions keeping the records, and do not indicate if people have simultaneous contact with related institutions at the same time (e.g., working in two jobs). They tend to contain a bias against short spells, and the contextual information about personal and socioeconomic characteristics typically needed for academic or policy research is sparse.

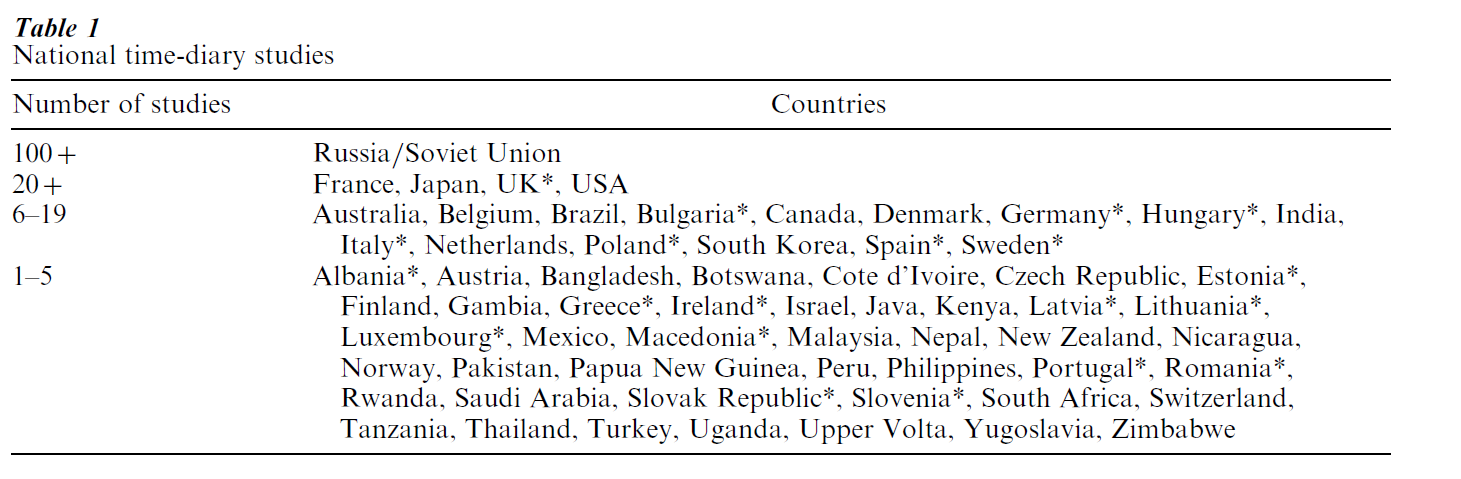

Many of the problems with the foregoing methods are solved if respondents are asked to provide a complete account of the sequence of events, during one or more days, within a framework of clock-times. This ‘diary’ approach, unlike the stylized estimate method, involves a narrative skill that is often called for in the course of daily life. Diary methods are by far the most widely used techniques for the estimation of time-use patterns: there are at least 400 such studies, from at least 80 countries, and more than half of these countries can provide at least one full national random sample of diary-based time-use evidence.

3. Diary Methods

The diary method provides a number of clear advantages, which stem from the fact that the narratives mirror, in a straightforward way, the structure of daily activities. Diaries require the respondent to engage in an active process of recall, in which they reconstruct the successive events of the day, so that the particular occurrences such as a trip to the doctor that disturbs the normal passage of the working day, emerge naturally as the respondent recollects ‘what happened next.’ Diary accounts are complete and continuous, so any respondent intending to suppress some activity must make a conscious effort to substitute some other activity. This will also tend to limit exaggeration of the duration of particular activities, since the potential for double counting (e.g., of a period as both work and leisure) that is entirely possible using the stylized estimates, is precluded in diary accounts. There are other advantages in the diary-reporting format for the analyst. Increasingly researchers are concerned to investigate the activity sequences themselves, or the times of the day at which activities occur; simultaneous activities can be properly investigated, and if multiple diaries are collected within a single household, researchers can use them to investigate patterns of copresence, interdependence, and cooperation.

The time-diary method itself is nevertheless not unproblematic. In particular, it produces some ‘underreporting of socially undesirable, embarrassing, and sensitive’ behaviors, including personal hygiene, sexual acts, and bathing (Robinson and Godbey 1997, p. 115). Techniques for persuading people to account completely for their days need some refinement.

4. Diary Data Collection

There are wide variations in the design of time-use diaries. The summary results seem fairly stable with respect to the different methods, and comparisons of different methodologies do not suggest any unequivocally dominant methodological choices (Harvey 1999, however, provides general-purpose recommendations). Choices are problematic (cost issues apart) because particular design characteristics affect respondent burden and hence response rates. There is a straightforward trade-off between a ‘heavy’ design, which yields a fuller picture of individuals’ activities but relatively low response, or a ‘light’ design providing a less complete picture, but with a higher response rate.

For example: diaries may cover longer or shorter periods. The problem, which is unusual in survey research terms, insofar as most personal characteristics are fixed at any historical point, is that individuals’ activities differ from day to day. Suppose all respondents do a weekly clothes wash, on one, randomly chosen, day of the week: a single-day diary will suggest that one-seventh of the sample spend a lot of time in laundry, and six-sevenths do none, where the reality is that all do on average a small amount. A short diary gives a spurious impression of interpersonal variability which is in fact largely intrapersonal. A week-long diary would reveal the real situation, but is of course very demanding for respondents.

There are two alternative modes of diary administration, conventionally referred to as ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’ studies, the former involving an interviewer-led and recorded process and the latter a self-completion instrument. The ‘yesterday’ diary normally does cover the previous day, as recall of events decays fairly rapidly, but it is practicable to collect useable information after a gap of two or even three days, and difficulties in recruiting respondents over the weekend may mean that this is necessary so as to ensure even coverage of the days of the week. The ‘tomorrow’ self-completion diary is left with the respondent by the interviewer with the instruction to make records as frequently as possible through the diary period so as to maximize the recall quality. Tomorrow instruments have normally covered either one or two days, but experience in The Netherlands and the UK shows that periods up to a full week are possible, although with reduced response rates.

A variety of interview technologies have been employed for yesterday diaries; in addition to conventional pen-and-paper personal interviews, there are examples of computer-aided personal interviews (CAPI), and computer-aided telephone interview (CATI) methods. Studies sometimes use a combination of yesterday and tomorrow with the self-completion instrument being posted back by the respondent. In this case the tomorrow shows lower and somewhat biased responses. For tomorrow diaries, response is substantially improved if the interviewer returns to collect the diary.

A second substantial design issue concerns the temporal framework within which the activities are recorded. A key decision here is whether to adopt an ‘event’ basis of recording (‘When did you wake up?’; ‘What did you do first?’; ‘When did you stop?’; ‘What did you do next?’). This style is appropriate for a ‘yesterday’ interview, but not for a tomorrow diary. For self-recording it is more appropriate to use a schedule with regular time slots, of 5–15 min (although slots of up to 30 min have been used, and the length of the slots may vary through the day and night); respondents indicate the duration of each activity on the schedule using lines, arrows or ditto marks.

Activities may be reported using either a ‘closed’ vocabulary, in which a predetermined set of activity codes is provided to cover the full range of possibilities, or an ‘open’ approach, in which respondents use their own words to describe the activities, these being coded subsequently. Respondents frequently find the ‘closed’ approach constraining, however well-designed the categories, and the choice of categories may to a limited degree influence the level of reporting (e.g., a more detailed classification of travel types leads to a small increase in estimates of travel time). However, the open approach has symmetrical shortcomings: respondents report at varying levels of detail, which are difficult to disentangle from genuine interpersonal differences.

For much of the day it is difficult to classify the current state as a single activity: ‘writing at the computer’ may be accompanied by ‘drinking coffee’ or ‘talking to my child.’ The normal practice is to ask respondents to record activities in an hierarchical manner: ‘What are/were you doing?’ ‘Were you doing anything else at the same time?’ Some studies ask respondents to record all activities in a nonhierarchical manner; but respondents tend to prefer opportunity to use a narrative mode (‘First I did this, and then I did that …’), which provides a hierarchy of primary and secondary activities. The hierarchy also simplifies the process of analysis, although there are ways of analyzing the data that are nonhierarchical but still conserve the 1440 min of the day. Other ancillary information included within the rows or columns of diary forms includes items such as ‘Who else is present engaged in the activity?’ and ‘Where are you?’—the latter sometimes also requesting information on modes of transport. National income accountants’ interest in nonmonetized economic activity has led to attempts to acquire ‘Who for?’ information, but these have not so far been successful. Specialized diary studies also include interpretative or affective information, (e.g., ‘Is this work?’ or ‘How much did you enjoy this?’) attached to each event or activity.

Beyond the design of the diary instrument, there are also various specialized sampling issues. Seasonal effects may be of importance; representative samples of time use require an even coverage across the year. There are serious practical difficulties but most national-scale samples attempt multiple sweeps during different parts of the year; the most developed approach to temporal sample design is found in Poland, whose 1970s and 1980s studies achieved approximately even numbers of diaries for each day of the year. Samples that include simultaneous diaries for all household members greatly extend the analytical usefulness of the evidence. Conventional ‘tomorrow’ studies include children down to the ages of 12 or even 10 years; and Italian national studies have, by a combination of simplified forms for younger children, and parental proxies for preliterate children, achieved total household coverage.

5. Time-Diary Research

Table 1 indicates the global extent of diary research. Large-scale national random sample studies have been conducted in each of three or more decades in 20 countries. The first cross-national comparative time-diary study was supported by UNESCO in 1965 (Szalai 1972). Twenty countries (marked with asterisks in Table 1) have participated in Eurostat’s 1996–2001 European Harmonized Time Use Study project. Results from the Multinational Time Use Study, providing evidence of change in time use over the period 1961–95 from 20 countries, are reported by Gershuny (2000).

Bibliography:

- Becker G 1965 A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal 80: 493–517

- Bourdieu P 1985 Distinction. RKP, London

- Gershuny J 2000 Changing Times. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Harvey A S 1999 Guidelines. In: Pentland W E, Harvey A S, Lawton M P, McColl M A (eds.) Time Use Research in the Social Sciences. Kluwer, New York, pp. 19–45

- Robinson J P, Godbey G 1997 Time for Life. Pennsylvania State University Press, Philadelphia, PA

- Szalai A (ed.) 1972 The Use of Time. Mouton, The Hague