View sample Teamwork And Team Training Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

During recent years, teams have emerged as the cornerstone of many organizations. Team efforts are required in many businesses and industries (e.g., government agencies, aviation operations, military organizations, and hospitals) to meet their missions and goals (Ilgen 1999). When applied correctly, teams may offer several advantages over individuals or groups. For example, teams can perform difficult and complex tasks, motivate their members effectively, and in some cases outperform individuals (Foushee 1984). Specifically, teams can be more productive, make better decisions (Orasanu and Fischer, 1997), perform better under stress, and make fewer errors (Wiener et al. 1993). When organized, designed, and managed correctly, teams can be a powerful organizational tool (Guzzo and Dickson 1996).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The purpose of this research paper is to provide a brief overview of what we have begun to learn about the nature of teamwork and what can we do to enhance it. Five questions will be discussed: (Sect.1) what is a team? (Sect.2) what are team competencies? (Sect.3) what is teamwork? (Sect.4) what is team training? and (Sect.5) what is team measurement? Several key concepts will be defined.

1. What Is A Team?

According to Salas and Cannon-Bowers (2000) a team can be defined as ‘a set of two or more individuals who must interact and adapt to achieve specified, shared, and valued objectives’ (p. 313). Teams must also have meaningful task interdependencies—the job cannot be done by a single individual—and usually task-relevant knowledge is distributed among the team members. Other characteristics of teams are that members: (a) have roles that are very defined and functional; (b) are hierarchically organized; (c) share two or more information sources; and (d) have a limited time span (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000).

This definition is important because it highlights the fact that not all teams are created equal. Teams differ from groups (e.g., task forces, committees) with respect to the degree of task interdependency, structure, and requirements (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000). In addition, teams differ from groups regarding essential knowledge and skills; necessity of critical team feedback for success; and development of shared goals, expectations, and vision. Since teamwork is characterized by synchronizing goal-directed behaviors, interdependent activities, and functions that are separate from the task itself, teams hold unique features, which most other small groups do not. Therefore, one needs to understand the competencies needed for team members to succeed in a team; they will be discussed next.

2. What Are Team Competencies?

In recent years, research has uncovered the knowledge, skills, and attitudes (i.e., competencies) necessary for effective team performance. These team competencies allow organizations to establish the appropriate requirements for their teams and strategies to enhance teamwork and performance. Teamwork competencies can be characterized as resources that team members draw from in order to function. As noted, they include knowledge, skills, and attitude-based factors.

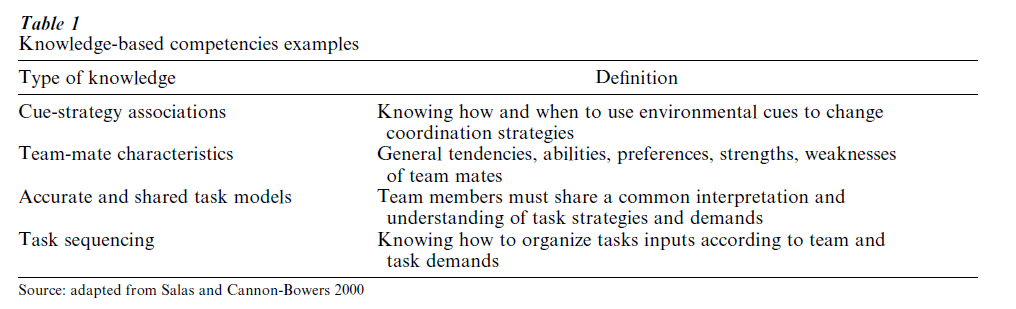

Knowledge-based competencies (i.e., what team members ‘think’) refers to the necessity of understanding facts, concepts, relations, and underlying foundations of information that a team member must have to perform a task. For teams to perform required tasks, they must possess a certain set of knowledge. (see Table 1 for some examples.) It has been noted that team members must have synchronized mental models (i.e., knowledge structures) about the roles of their teammates, the tasks, and the situations that the team encounters (see Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998). Expectations created by these knowledge structures allow team members individually to generate predictions concerning how to perform during routine and novel situations that the team encounters. It has also been shown that it is necessary for team members to possess knowledge about the purpose and objectives of their mission, the available and needed rewards, and the expected norms to be followed.

An important knowledge-based team competency, cue/strategy associations, has been suggested as important for the functioning of teams in complex, knowledge-rich environments (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000). Through cue strategy associations, team members are triggered to perform in a certain way by a pattern of cues in the environment. Essentially, team members make associations between this pattern of cues and what they should do. Teams are able to adapt, reallocate functions, and occasionally perform without the need for overt communication because of this knowledge. While the cue strategy associations competency is key, there are other knowledge-based competencies that are useful to teams such as: knowledge of teammate characteristics, accurate and shared task models, and team sequencing (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000).

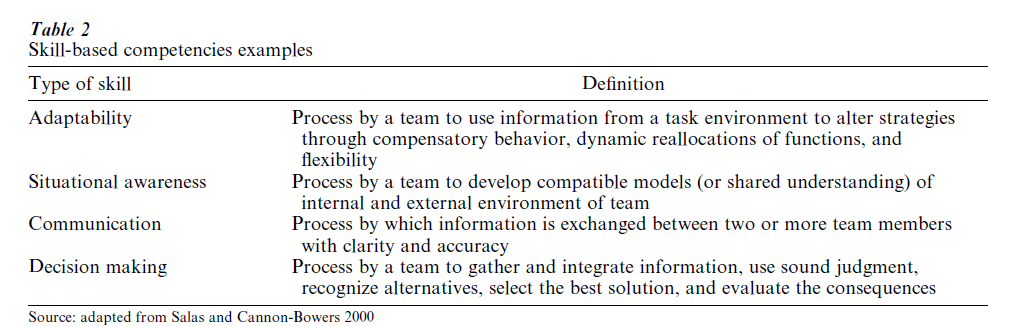

Skill-based competencies (i.e., what team members ‘do’) are the necessary behavioral sequences and procedures needed for task performance. It is clear that team members must behave in certain ways and do certain things in order to achieve their goals. Specifically, teams perform various actions—coordination, communication, strategization, adaptation, and synchronization of task-relevant information. The information can be verbal, nonverbal, or visual. Team members require skills to perform in a fashion that is accurate and timely. As with knowledge-based competencies, there are also many skill-based competencies required for effective team performance (see Table 2 for more examples).

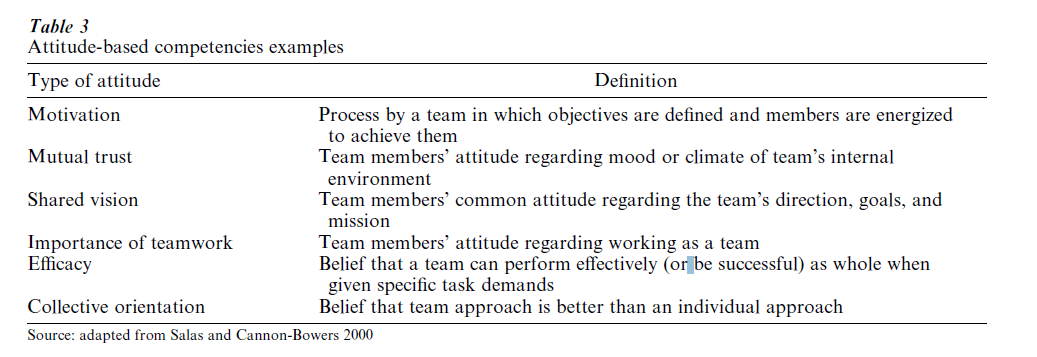

Attitude-based competencies (i.e., what team members ‘feel’) refer to the affective components needed to perform the task. Teamwork is greatly affected by how team members feel about each other and the task. Due to considerable research, several attitude-based competencies have emerged (i.e., motivation, trust, shared vision, importance of teamwork) which affect teamwork and team outcomes (see Table 3 for a more in-depth description). For example, collective self-efficacy (i.e., the belief that the team can perform the task) and collective orientation are important in team functioning.

The team competencies described here are the necessary elements for effective teamwork and become the desired target when developing team training. The final goal of team training is to improve and foster effective teamwork. To do this, researchers must uncover, analyze, and address the necessary knowledge-, skill-, and attitude-based competencies, while also considering the nature of the team task (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000). A discussion of what comprises teamwork follows.

3. What Is Teamwork?

Teamwork can be defined as the ability of team members to work together, communicate effectively, anticipate and meet each other’s demands, and inspire confidence, resulting in a coordinated collective action. However, a clear and direct answer to the question ‘What is teamwork?’ has not been provided. According to McIntyre and Salas (1995), teamwork is a critical component of team performance and requires an explanation of how a team behaves. There are four key behavioral characteristics that compose teamwork: (a) performance monitoring, (b) feedback, (c) closed-loop communication, and (d) back-up behaviors.

The first requirement of teamwork is that team members monitor the performance of others while carrying out their own task. Monitoring ensures that members are following procedures correctly and in a timely manner, while also ensuring that operations are working as expected. Performance monitoring is accepted as a norm in order to improve the performance of the team in addition to establishing a trusting relationship between members.

Next as a follow-up activity to monitoring, feedback on the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of performance is passed along to members being monitored. Team members must feel at ease when providing feedback for teamwork to be effective. No obstacles (i.e., rank, tenure) should stand between members who are giving and receiving this vital information. Free-flowing feedback exists in the highest level of teamwork.

Teamwork involves the effective communication between a sender and receiver. Closed-loop communication describes the information exchange that occurs in successful communication. There is a sequence of behaviors that is involved in closed-loop communication: (i) the message is initiated by the sender; (ii) the message is accepted by the receiver and feedback is provided to indicate that it has been received; (iii) the sender double-checks with the receiver to ensure that the intended message was received. This type of communication is especially apparent in emergency situations.

Finally, back-up behaviors (i.e., the willingness, preparedness, and liking to back team members during operations) are required for effective teamwork. Team members must be willing to help when they are needed and must accept help when needed without feeling they are being perceived as weak. This requires that members know the expectations of their jobs while also knowing the expectations of others with whom they are interacting.

These four complex behavioral characteristics— performance monitoring, feedback, closed-loop communication, and backing-up behaviors—are necessary for effective teamwork. A failure of one of these aspects could result in ineffective team performance. Next, team training and four training strategies will be defined.

4. What Is Team Training?

Team training can be defined as a set of tools and methods that form an instructional strategy in combination with requisite competencies and training objectives (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 1997). It is concerned with the design and development of theoretically based instructional strategies for influencing the processes and outcomes of teams. Team training consists of strategies derived from synthesizing a set of outputs from tools (e.g., team task analysis); delivery methods (e.g., information-based); and content (e.g., knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 1997, Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998).

Team training has one basic objective—to impact crucial team competencies. More specifically, team training seeks to foster in the team members, sufficient and accurate mental representations of the team task and role structure, and the process by which members interact.

There are four team training strategies that have emerged in the literature and will be discussed—team coordination training, cross-training, team self-correction training, and team leadership training.

Team coordination training, also known as team adaptation and coordination training, is the most common team training strategy (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 1997, Entin and Serfaty 1999). This training strategy is widely used in the aviation industry and is known in commercial aviation as crew resource management, and in military aviation as aircrew coordination training (Wiener et al. 1993).

First, team coordination training is based on the shared mental model (SMM) theory. SMM theory posits that shared knowledge enables team members to predict the needs of the task and anticipate the actions of other team members, allowing them to adjust their behavior accordingly (Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998). Expectations of what is likely to happen, are formed by team members, as a means to guide action. Especially in a novel situation (when they cannot strategize overtly) teams must exercise shared models of the task and team in order to maintain performance. Thus, the role of shared mental models in explaining team behavior stems from the team’s ability to allow its members to generate predictions about team and task demands in the absence of communication. The idea of SMMs and their relation to team effectiveness provide several implications for the understanding of team performance and training (see Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998).

Team coordination training was designed in order to reduce communication and coordination overhead within the team. Its development was a result of testing and observing successful teams who adapted to in- creased levels of stress by changing their coordination strategies. Research has shown that these teams performed significantly better on posttraining scenarios than did teams assigned to control conditions. Changes in communication dynamics of team members under stress were used to enhance team performance. Practice on effective teamwork strategies is important in order to change behaviors so they adapt to increasing task demands, which has been demonstrated through team coordination training (Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998).

Next, the cross-training strategy, also based on the SMM theory, is necessary to lessen the decline in team performance due to turnover. It should be designed so that commonly shared expectations, called inter-positional knowledge, regarding specific team-member functioning can be developed. To accomplish this, all parties can be provided with ‘hands-on’ experience regarding the tasks, roles, and responsibilities of other members within the team. Cross-training research has shown that it is an important determinant of effective communication, task coordination, and performance (see Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998).

Third, team self-correction training emphasizes the need for team members to provide each other with feedback regarding their performance on a task and the underlying expectations for effective performance. This helps to clarify correct expectations and intentions between members, while facilitating modifications of expectations and intentions that are incorrect. This approach trains teams to observe both their own and each other’s performance in order to provide feedback following task completion. Teams are then able to modify their knowledge, skills, and attitudes without intervention from an outside source. Along with team coordination training and cross-training, team self-correction training is based on the SMM theory (see Cannon-Bowers and Salas 1998).

Finally, team leadership training is another team training strategy. When training team competencies, or KSAs, the training begins with the team leader. However, effective team leadership requires: (a) competence that is both technical and operational, (b) knowledge of how to lead a team, and (c) willingness to listen and use team members’ expertise. A critical factor in the success of a team is the team leader. A team leader, through specific instruction, can guide the team members to develop those KSAs needed to perform effectively. The influence of a team leader can impact, either advantageously or otherwise, the learning skills of a team and the instructional value of an experience. However, the team leader may not possess the skills needed to accomplish the task. To give him the necessary skills, team leadership training should be implemented. The team leader should be taught to recognize and target crucial teamwork skills needed for training such as communication, coordination, decision-making, and adaptability flexibility. In the following section, what needs to be measured to diagnose effective or ineffective teamwork is discussed.

5. What Is Team Measurement?

Measurement of team performance is a component that is critical in team training. Salas and Cannon-Bowers (2000) state that ‘measurement is the basis upon which we assess, diagnose, and remediate performance’ (p. 322). They continue by noting that learning is promoted and facilitated through measurement. Measurement also produces and provides information about skill acquisition and a metric upon which capabilities and limitations of human performance can be judged. For team training, the dynamic, multi-level nature of teamwork must be able to be captured by the measurement approach. Measurement not only serves to describe teamwork, but it can also be used in the development and guidance of instructional events. The multiple pieces of information needed for feedback must be integrated by a complete team performance measurement system. In addition, the measurement system must have the following features to foster team training: be theoretically based; assess and diagnose team performance; address team outcomes as well as processes; capture moment-to-moment behaviors, cognitions, attitudes, and strategies; consider multiple levels of analysis; consider multiple methods of measurement; provide a basis for remediation, and rely on observation by experts (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000).

According to Salas and co-workers, team performance measurement should be able to: (a) identify the processes linked to team outcomes, (b) distinguish between deficiencies in individual and team levels, (c) describe interactions between team members to capture occurring moment-to-moment changes, (d) produce assessments that may be used to deliver performance feedback, (e) produce reliable and defensible evaluations, and (f ) support operational use (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000).

Performance measurement is done for the purpose of inferring something about the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of the team member. Observations of critical team behaviors is also required of team performance measurement in order for inferences to be made about categories of behavior or dimensions such as communication, coordination, and adaptability. Techniques have been established for measuring teamwork skills and for studying the relationship between teamwork and team task performance (Ilgen 1999).

A team task analysis, which is needed to uncover the coordination demands of complex tasks, is generally the first step for measuring team performance and designing team training. These analyses provide information about the necessary team learning objectives and team competencies. Key information necessary for designing and delivering team training is also generated by the team task analysis. In addition, team task analysis provides information about the KSAs, cues, events, actions, coordination demands, and communication flows needed for teamwork to be effective. Typically, subject matter experts (SMEs) are asked to provide information on these aspects of the task. This information is then utilized to specify objectives of team training, to create a task inventory that focuses on those objectives, and to guide training scenario development (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2000).

There are two methodologies that need to be considered for measuring team skills: (a) team vs. individual measures, and (b) outcome vs. process measures. Individual measures assess the skills required to perform and meet individual tasks and responsibilities. On the other hand, teamwork measures focus on the coordination requirements (e.g., performance monitoring, feedback, communication, and back-up behaviors) that are necessary between team members. Process measures (i.e., how the task was accomplished) are important for determining problems in performance that may prevent successful outcomes. However, successful outcomes can be achieved when processes are flawed. Outcome measures usually rely on opinions from experts or automated recording of performance. Because outcome measures do not provide information that is useful in determining the cause of poor performance or performance improvement, it is necessary to measure both process and outcomes to ensure that team performance is effective.

It is important when measuring team performance and training to follow the theory and methodologies outlined above. The team task analysis, or theory level, will allow the researcher to define the critical dimensions, behaviors, objectives, and competencies required of the team training. Team performance and training should be measured next. Measurement of team skills is usually accomplished using the team vs. individual measures approach and/or the outcome vs. process measures approach. It is important to measure all aspects of a team’s performance to ensure its effectiveness.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this research paper has been to provide information regarding teamwork and team training. The authors have attempted to present an overview of these areas by providing definitions of a team, teamwork, and team training. In addition, the necessary team competencies—knowledge, skills, and attitudes—were briefly described. It should be noted that the KSAs mentioned are neither exclusive nor exhaustive. In addition, several team training strategies necessary for effective team performance were discussed. Finally, team measurement through a team task analysis (i.e., development of team training objectives and competencies) and methodologies were shown to be an important part of effective team performance.

Bibliography:

- Cannon-Bowers J A, Salas E 1998 Individual and team decision making under stress: Theoretical underpinnings. In: Cannon-Bowers J A, Salas E (eds.) Making Decisions under Stress: Implications for Individual and Team Training. APA, Washington, DC, pp. 17–38

- Entin E E, Serfaty D 1999 Adaptive team coordination. Human Factors 41(2): 312–25

- Foushee H C 1984 Dyads and triads at 35,000 feet: Factors affecting group process and aircrew performance. American Psychologist 39(8): 885–93

- Guzzo R A, Dickson M W 1996 Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. Annual Review of Psychology 47: 307–38

- Ilgen D R 1999 Teams embedded in organizations: Some implications. American Psychologist 54(2): 129–39

- McIntyre R M, Salas E 1995 Measuring and managing for team performance: Emerging principles from complex environments. In: Guzzo R, Salas E, et al. (eds.) Team Effectiveness and Decision Making in Organizations. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA, pp. 149–203

- Orasanu J, Fischer U 1997 Finding decisions in natural environments: The view from the cockpit. In: Zsambok C E, Klein G (eds.) Naturalistic Decision Making. Expertise: Research and Applications. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 343–57

- Salas E, Bowers C A, Edeus E (eds.) 2001 Improving Teamwork in Organizations: Applications of Resource Management Training. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

- Salas E, Cannon-Bowers J A 1997 Methods, tools, and strategies for team training. In: Quinones M A, Ehrenstein A (eds.) Training for a Rapidly Changing Workplace: Applications of Psychological Research. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 249–79

- Salas E, Cannon-Bowers J A 2000 The anatomy of team training. In: Tobias S, Fletcher J D (eds.) Training and Retraining: A Handbook for Business, Industry, Government, and the Military. Macmillan, New York, pp. 312–35

- Turner M E (ed.) 2001 Groups at Work: Theory and Research. Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ

- Wiener E L, Kanki B G, Helmreich R L (eds.) 1993 Cockpit Resource Management. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, pp. 479–501