View sample Syntax-Semantics Interface Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Anybody who speaks English knows that (1) is a sentence of English, and also has quite a precise idea about what (1) means.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

(1) Every boy is holding a block.

English speakers know for infinitely many sentences that they are sentences of English, and they also know the meaning of these infinitely many sentences. A central idea of generative syntax is that the structure of a sentence is given by a recursive procedure, as this provides the means to derive our knowledge about the infinite number of sentences with finite means. For the same reason, semanticists have developed recursive procedures that assign a meaning to sentences based on the meaning of their parts.

The syntax–semantics interface establishes a relationship between these two recursive procedures. An interface between syntax and semantics becomes necessary only if they indeed constitute two autonomous systems. This is widely assumed to be the case, though not entirely uncontroversial as some approaches do not subscribe to this hypothesis.

Consider two arguments in favor of the assumption that syntax is autonomous: one is that there are apparently purely formal requirements for the well-formedness of sentences. For example, lack of agreement as in (2) renders (1) ill-formed (customarily marked by prefixing the sentence with an asterisk), though subject–verb agreement does not seem to make any contribution to the meaning of (1).

(2) *Every boy hold a block.

The special role of uninterpretable features for syntax comes out most sharply in recent work by Chomsky (1995), who regards it as one of the main purposes of syntax to eliminate such uninterpretable features before a sentence is interpreted.

On the other hand, there are also sentences that are syntactically well-formed, but do not make any sense (often marked by prefixing the sentence with a hatch mark). Chomsky’s (1957, p. 15) famous example in (a) makes this point, and so does (b).

(3) (a) # Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

(b) # She arrived for an hour.

Independent of the value of these arguments, the separation of syntax and semantics has led to tremendous progress in the field. So, at least it has been a successful methodological principle.

1. Basic Assumptions

Work on the syntax–semantics interface by necessity proceeds from certain assumptions about syntax and semantics. We are trying to keep to a few basic assumptions here. In the specialized articles on generative syntax (Linguistics: Incorporation), and quantifiers (Quantifiers, in Linguistics) many of these assumptions are discussed and justified in more depth.

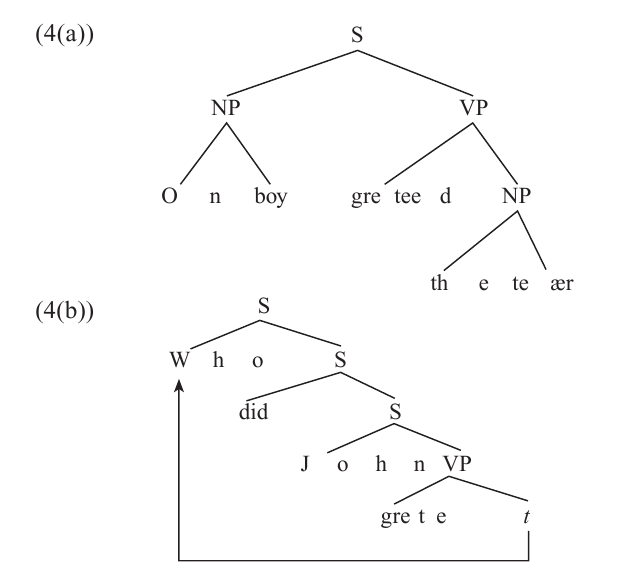

For the syntax, we assume that sentences have a hierarchical constituent structure that groups words and subconstituents into constituents. Also, we assume that constituents can be moved from one part of the tree structure to another, subject to constraints of the kind Ross (1967) first described. The constituent structure of a sentence is captured by the kind of phrase structure tree illustrated in (4)(a). (4)(b) shows a phrase structure tree with a movement relation.

The task of semantics is to capture the meaning of a sentence. Consider first the term ‘meaning.’ In colloquial use, ‘meaning’ includes vague associations speakers may have with a sentence that do not exist for all speakers of a language: e.g., the sentence ‘I have a dream’ may have a special meaning in this colloquial sense to people familiar with Martin Luther King.

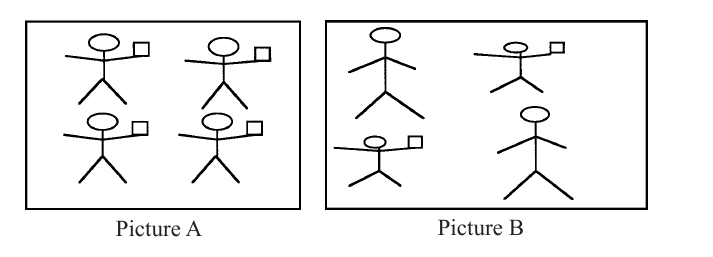

Semantics, however, is at present concerned only with reproducible aspects of sentence meaning. In particular, semanticists have focused on the question of whether a sentence is judged true or false in a certain situation. Part of what any speaker of English knows about the meaning of (1) is that it is true in the situation shown in picture A, but false in the situation shown in picture B.

(5) Every boy is holding a block.

All speakers of English are equipped with certain mental mechanisms that enable them to make this truth value judgment for (1) and similar judgments for infinitely many other sentences. An explicit theory can be given using techniques similar to those used in mathematical logic. In this approach, the meaning of a constituent is modeled by a mathematical object (an individual, a function, a set, or a more complicated object). Complete declarative sentences such as (1) correspond to functions that assign to possible situations one of the truth values True or False. The basic intuition of entailment between sentences as in (6) is captured if for every situation to which the meanings of the premises (a) and (b) assign True, the meaning of the conclusion (c) also assigns to this situation True.

(6) (a) Every boy is holding a block.

(b) John is a boy.

(c) Therefore, John is holding a block.

2. Syntax–Semantics Correspondences

Though syntax and semantics are two autonomous recursive procedures, most researchers assume that there is a relationship between the two to be captured by the theory of the syntax–semantics interface. In particular, it seems to be the case that the steps of the recursion are largely the same. In other words, two phrases that form a syntactic constituent usually form a semantic constituent as well (Partee (1975) and others).

Consider (7) as an illustration of this.

(7) (a) A smart girl bought a thin book.

(b) A thin girl bought a smart book.

Subject Verb Object

Syntacticians have argued that the subject and the object in (6) form constituents, which we call noun phrases (abbreviated as NPs). We see in (6) that the adjective that occurs in a NP also makes a semantic contribution to that NP. This is not just the case in English: as far as we know, there is no language where adjectives occurring with the subject modify the object, and vice versa.

Further evidence for the close relation of syntactic and semantic constituency comes from so many phenomena that we cannot discuss them all. Briefly consider the case of idioms. On the one hand, an idiom is a semantically opaque unit whose meaning does not derive from the interpretation of its parts in a transparent way. On the other hand, an idiom is syntactically complex. Consider (8).

(8) (a) Paul kicked the bucket. (‘Paul died.’)

(b) The shit hit the fan. (‘Things went wrong.’)

The examples in (8) show a verb–object idiom and a subject–verb–object idiom. What about a subject–verb idiom that is then combined transparently with the object? Marantz (1984, pp. 24–28) claims that there are no examples of this type in English. Since syntacticians have argued that the verb and the object form a constituent, the verb phrase, that does not include the subject (the VP in (4)), Marantz’s generalization corroborates the claim that idioms are always syntactic constituents, which follows from the close relationship between syntax and semantics.

If syntactic and semantic recursion are as closely related as we claim, an important question is the semantic equivalent of syntactic constituent formation. In other words, what processes can derive the interpretation of a syntactically complex phrase from the interpretation of its parts? Specifically, the most elementary case is that of a constituent that has two parts. This is the question to which the next two sections provide an answer.

2.1 Constituency

2.1.1 Predication As Functional Application. An old intuition about sentences is that the verb has a special relationship with the subject and the objects. Among the terms that have been used for this phenomenon are ‘predication’, which we adopt, ‘theta marking,’ and ‘assigns a thematic role.’

(9) John gave Mary Brothers Karamazo .

One basic property of predication is a one-to-one relation of potential argument positions of a predicate and actually filled argument positions. For example, the subject position of a predicate can only contain one nominal: (a) shows that two nominals are two many; and (b) shows that none is not enough.

(10) (a) *John Bill gave Mary Brothers Karamazo .

(b) *gave Mary Brothers Karamazo .

Chomsky (1981) describes this one-to-one requirement between predication position and noun phrases filling this position as the theta-criterion.

The relationship between ‘gave’ and the three NPs in (9) is also a basic semantic question. The observed one-to-one correspondence has motivated an analysis of verbs as mathematical functions. A mathematical function maps an argument to a result. Crucially, a function must take exactly one argument to yield a result, and therefore the one-to-one property of predication is explained. So, far example, the meaning of ‘gave Mary Brothers K.’ in (10) would be captured as a function that takes one argument and yields either True or False as a result, depending on whether the sentence is true or false.

The phrase ‘gave Mary Brothers K.’ (the verb phrase) in (9) is itself semantically complex, and involves two further predication relations. The meaning of the verb phrase, however, is a function. Therefore the semantic analysis of the verb phrase requires us to adopt higher order functions of the kind explored in mathematical work by Schonfinkel (1924) and Curry (1930). Namely, we make use of functions the result of which is itself a function. Then, a transitive verb like ‘greet’ is modeled as a function that, after applying to one argument (the object), yields as its result a function that can be combined with the subject. The ditransitive verb ‘give’ is captured as a function that yields a function of the same type as ‘greet’ after combining with one argument.

Functional application is one way to interpret a branching constituent. It applies more generally than just in NP–verb combinations. Another case of predication is that of an adjective and a noun joined by a copula, as in (11). We assume here that the copula is actually semantically empty (i.e., a purely formal element), and the adjective is a function from individuals to truth values, mapping exactly the red-haired individuals on to True (see Rothstein 1983).

(11) Tina is red-haired.

Similarly, (12) can be seen as a case of predication of ‘girl’ on the noun ‘Tina.’ For simplicity, we assume that in fact not only the copula but also the indefinite articles in (12) are required only for formal reasons. Then, ‘girl’ can be interpreted as the function mapping an individual who is a girl on to True, and all other individuals on to False.

(12) Tina is a girl.

2.1.2 Predicate Modification As Intersection. Consider now example (13). In keeping with what we said about the interpretation of (11) and (12) above, (13) should be understood as a predication with the predicate ‘red-haired girl.’

(13) Tina is a red-haired girl.

The predicate ‘red-haired girl’ would be true of all individuals who are girls and are red-haired. But clearly, this meaning is derived systematically from the meanings of ‘red-haired’ and ‘girl.’ This is generally viewed as a second way to interpret a branching constituent: by intersecting two predicates, and essentially goes back to Quine (1960).

2.1.3 Predicate Abstraction. A third basic interpretation rule can be motivated by considering relative clauses. The meaning of (14a) is very similar to that of (13). For this reason, relative clauses are usually considered to be interpreted as predicates (Quine 1960, p. 110 f.).

(14) (a) Tina is a girl who has red hair.

(b) Tina is a girl who Tom likes.

Syntacticians have argued that the relative pro- nouns in (14) are related in some way to an argument position of the verb. We adopt the assumption that this relationship is established by syntactic movement of the relative pronoun to an initial position of the relative clause.

(15) whox x has red hair

whox Tom likes x

Looking at the representation in (15), the semantic contribution of the relative pronoun is to make a predicate out of a complete clause which denotes a truth value. An appropriate mathematical model for this process is lambda-abstraction (Church 1941). The definition in (16) captures the intuition that (14b) entails the sentence ‘Tom likes Tina,’ where the argument of the predicate is inserted in the appropriate position in the relative clause (see, e.g., Cresswell (1973) or Partee et al. (1990) for more precise treatments of lambda abstraction).

(16) [λx XP] is interpreted as the function that maps an individual with name A to a result r where r is the interpretation of XP after replacing all occurrences of x with A.

Functional application, predicate modification and lambda abstraction are probably the minimal inventory that is needed for the interpretation of all hypothesized syntactic structures.

2.2 Scope

2.2.1 Quantifier Scope. A second area where a number of correspondences between syntax and semantics have been found are semantic interactions between quantificational expressions. Consider the examples in (17) (adapted from Rodman (1976, p. 168):

(17) (a) There’s a ball that every boy is playing with.

(b) Every boy is playing with a ball.

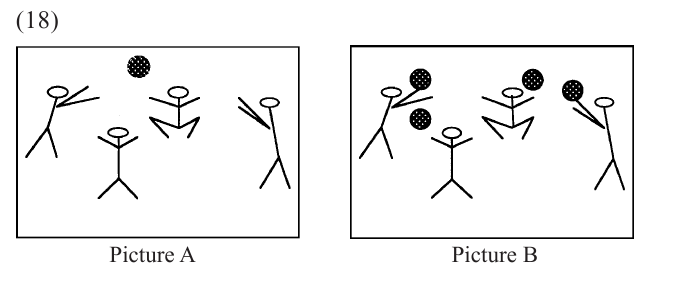

The difference between (17a) and (17b) is that only (17b) is true when every boy is playing with a different ball, as in picture B; (17a) is only judged to be true in the situation depicted in picture A, where every boy is playing with the same ball.

The semantic difference between (17a) and (17b) correlates with a difference in syntactic structure. Namely, in (17b) ‘a ball’ is part of the sister constituent of ‘every boy,’ while it is not so in (17a).

The special role the sister constituent plays for semantic interpretation was first made explicit by Reinhart (1976) building on the work of Klima (1964) and others. She introduced the term c-command for the relationship where a phrase enters with any other phrase inside its sister constituent, and proposed that the domain of c-commanded phrases (i.e., the sister constituent) is the domain of semantic rule application. The c-command domain is then equated with what logicians call the scope.

On the recursive interpretation procedure developed in the previous section, Reinhart’s generalization is captured in a straightforward manner. This can be seen without being precise about the semantics of quantifiers (see Sect. 3.1). Consider the interpretation of the relative clause constituent in (a), which is shown with the lambda operator forming a predicate in (19). This predicate will only be true of an object a if every boy is playing with a. Such an individual is found in picture B, but not in picture A.

(19) Every boy is playing with x.

For sentence (17b), however, we want to interpret the verb phrase ‘is playing with a ball’ as a predicate that is true of an individual a, if there is some ball that a is playing with. (Below, in Sect. 3.2, we sketch a way to derive this meaning of VP from the meanings of its parts.) Crucially, this predicate is fulfilled by every boy in both picture A and picture B.

2.2.2 Binding. A second case where c-command is important is the binding of pronouns by a quantificational antecedent. Consider the examples in (20).

(20) (a) Every girl is riding her bike.

(b) Every girl is riding John’s bike.

Sentence (a) is judged true in a situation where the girls are riding different bicycles—specifically, their own bicycles. Example (b), however, is only true if John’s bike is carrying all the girls. The relationship between the subject ‘every girl’ and the pronoun ‘her’ in (a) can only be made more precise by using the concept of variable binding that has its origin in mathematical logic. (Note that, for example, the relevant interpretation of (a) is not expressible by replacing the pronominal with its antecedent ‘every girl,’ since this would result in a different meaning.)

We assume that the interpretation of the VP in (20a) can be captured as in (21) following Partee (1975) and others.

(21) λx is riding x’s bike.

The relevance of c-command can be seen by com- paring (20a) with (22). Though (22) contains the NP ‘every girl’ and the pronoun ‘her,’ (22) cannot be true unless all the boys are riding together on a single bike. The interpretation that might be expected in (22) in analogy to (20a) but which is missing can be paraphrased as ‘For every girl, the boys that talked with her are riding her bike.’

(22) The boys who talked with every girl are riding her bike.

The relevance of c-command corroborates the recursive interpretation mechanism that ties syntax and semantics together. Because binding involves the interpretation mechanism (16) operating on the sister constituent of the λ-operator, only expressions c- commanded by a λ-operator can be bound by it. In other words, an antecedent can bind a pronoun only if the pronoun is in the scope of its λ-operator.

3. Syntax–Semantics Mismatches

3.1 Subject Quantifiers

When we consider the semantics of quantifiers in more detail, it turns out that the view that predication in syntax and functional application in semantics have a one-to-one correspondence, as expressed above, is too simple. Consider example (23) which is repeated from (1).

(23) Every boy is holding a block.

Assume that the verb phrase ‘is holding a block’ is a one-place predicate that is true of any individual who is holding a block. Our expectation is then that the interpretation of (23) is achieved by applying this predicate to an individual who represents the interpretation of the subject ‘every boy.’ But some reflection shows that this is impossible to accomplish—the only worthwhile suggestion to capture the contribution of ‘every boy’ to sentence meaning by means of one individual, is that ‘every boy’ is interpreted as the group of all boys. But the examples in (24) show that ‘every boy’ cannot be interpreted in this way.

(24) (a) Every boy (*together) weighs 50 kilos.

(b) All the boys (together) weigh 50 kilos.

The interpretation of (24) cannot be achieved by applying the predicate that represents the VP meaning to any individual. It can also be seen that predicate modification cannot be used to assign the right interpretation to examples like (24a). The solution that essentially goes back to Frege (1879) and was made explicit by Ajdukiewicz (1935) is that actually the quantificational subject is a higher order function that takes the VP predicate as its argument, rather than the other way round. This interpretation is given in (25):

(25) [every boy] is a function mapping a predicate

P to a truth value, namely it maps P to True if

P is true of every boy.

Note that this analysis still accounts for the exactly one-argument requirement, which was observed above, because the result of combining the subject quantifier and the VP is a truth value, and therefore cannot be combined with another subject quantifier.

The Frege/Ajdukiewicz account of (23) does, however, depart from the intuition that the verb is predicated of the subject. Note that the semantic difference between quantifiers and nonquantificational NPs does not affect the syntax of English verb–subject relationships. Still in (1) the verb agrees with the subject, and the subject must precede the verb.

3.2 Object Quantifiers

Consider now (26) with a quantificational noun phrase in the object position. We argued in Sect. 2.1.1 that the interpretation of a transitive verb is given by a higher order function that takes an individual as an argument and results in a function that must take another individual as its argument before resulting in a truth value. But then (26) is not interpretable if we assume the Frege/Ajdukiewicz semantics of quantifiers.

(26) John greeted every boy. From the partial account developed up to now, it follows that ‘greet’ and ‘every boy’ should be combined semantically to yield a predicate representing the meaning of the VP. However, the meaning of ‘every boy’ is a higher order predicate that takes a predicate from individuals to truth values as its argument. But the meaning of ‘greet’ is not such a one-place predicate.

Any solution to the interpretability problem we know of posits some kind of readjustment process. One successful solution is to assume that before the structure of (26) is interpreted, the object quantifier is moved out of the verbal argument position (see, e.g., Heim and Kratzer 1998). For example the structure shown in (27) is interpretable.

(27) John λx [every boy] λy [x greeted y]

The movement process deriving (27) from (26) is called ‘quantifier movement.’ Quantifier movement in English is not reflected by the order in which words are pronounced, but this has been claimed to be the case in Hungarian (Kiss 1991).

3.3 Inverse Scope

The original motivation for quantifier movement was actually not the uninterpretability of quantifiers in object position, but the observation that the scope relations among quantifiers are not fixed in all cases. In example (17a) in Sect. 2.2.1, the scopal relation among the quantificational noun phrases was fixed. But consider the following sentence:

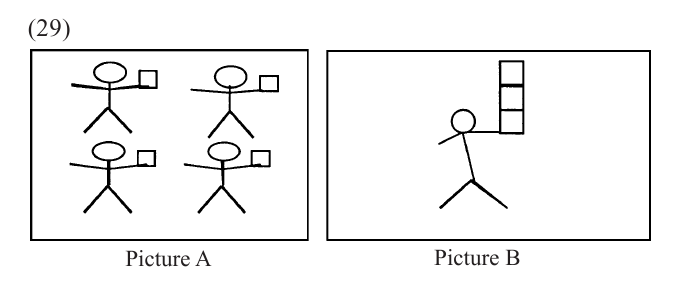

(28) A boy held every block.

The example is judged true in the situation in picture A, though there is no single boy such that every block was held by him.

The truth of (28) in this situation is not predicted by the representation in (30) that in some way maintains the syntactic constituency of the verb and the object to the exclusion of the subject.

(30) [a boy] λx [every block] λy [x held y]

For this reason, May (1977) and Chomsky (1975) propose to allow also quantifier movement that creates a constituent which includes the subject and the verb but not the object (similar ideas go back to Montague (1970) and Lewis (1972)). This structure is shown in (31).

(31) [every block] λy [a boy] λx [x held y]

Hence, the hypothesis that movement of quantificational noun phrases prior to interpretation is possible (and indeed obligatory in some cases) provides a solution not only for the problem with interpreting object quantifiers, but also for the availability of inverse scope in some examples.

4. Concluding Remarks

Many of the questions reviewed above are still topics of current research. We have based our discussion on the view that syntax and semantics are autonomous, and that there is a mapping from syntactic structures to interpretation. However, recent work by Fox (2000) argues that in some cases properties of interpretation must be visible to the syntax of quantifier movement. As the basic inventory of interpretation principles, we have assumed functional application, predicate modification, and lambda abstraction over variables. Other approaches, however, make use of function composition and more complex mathematical processes to eliminate lambda abstraction (Jacobson and others). In a separate debate, Sauerland (1998) challenges the assumption that movement in relative clauses should be interpreted as involving binding of a plain variable in the base position of movement. While the properties of scope and binding reviewed in Sect. 2.2 are to our knowledge uncontroversial, current work extends this analysis to similar phenomena such as modal verbs, tense morphemes, comparatives and many other topics (Stechow and Wunderlich (1991) give a comprehensive survey).

Research activity on the syntax–semantics interface is currently expanding greatly, as an increasing number of researchers become proficient in the basic assumptions and the formal models of the fields of both syntax and semantics. Almost every new issue of journals such as Linguistic Inquiry or Natural Language Semantics brings with it some new insight on the questions raised here.

Bibliography:

- Ajdukiewicz K 1935 Die syntaktische Konnexitat. Studia Philosophica 1: 1–27

- Chomsky N 1957 Syntactic Structures. Mouton, Den Haag

- Chomsky N 1975 Questions of form and interpretation. Linguistic Analysis 1: 75–109

- Chomsky N 1981 Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris, Dordrecht

- Chomsky N 1995 The Minimalist Program. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Church A 1941 The Calculi of Lambda-Conversion. Princeton University Press, Princeton, Vol. 6

- Cresswell M J 1973 Logic and Languages. Methuen, London

- Curry H B 1930 Grundlagen der kombinatorischen Logik. American Journal of Mathematics 50: 509–36

- Fox D 2000 Economy and Semantic Interpretation. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Frege G 1879 Begriff Eine der arithmetischen nachgebildete Formelsprache des reinen Denkens. Neubert, Halle

- Heim I, Kratzer A 1998 Semantics in Generative Grammar. Blackwell, Oxford

- Jacobson P 1999 Towards a variable-free semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 22: 117–84

- Kiss K 1991 Logical structure in linguistic structure. In: Huang J, May R (eds.) Logical Structure and Linguistic Structure. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp. 111–47

- Klima E 1964 Negation in English. In: Fodor J A, Katz J J (eds.) The Structure of Language. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp. 246–323

- Lewis D 1972 General semantics. Synthese 22: 18–67

- Marantz A 1984 On the Nature of Grammatical Relations. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- May R 1977 The grammar of quantification. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT

- Montague R 1970 Universal grammar. Theoria 36: 373–98

- Partee B H 1975 Montague grammar and transformational grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 6: 203–300

- Partee B H, ter Meulen A, Wall R E 1990 Mathematical Methods in Linguistics. Kluwer, Dordrecht

- Quine W 1960 Word and Object: Studies in Communication. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Reinhart T 1976 The syntactic domain of anaphora. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT

- Rodman R 1976 Scope phenomena, movement transformations, and relative clauses. In: Partee B H (ed.) Montague Grammar. Academic Press, New York

- Ross J R 1967 Constraints on variables in syntax. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT

- Rothstein S D 1983 The syntactic form of predication. Ph.D. thesis, MIT

- Sauerland U 1998 The meaning of chains. Ph.D. thesis, MIT

- Schonfinkel M 1924 Uber die Bausteine der mathematischen Logik. Mathematischen Annalen 92: 305–16

- Stechow A von, Wunderlich D 1991 Semantik. Ein internationales Handbuch zeitgenossischer Forschung. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York