View sample Structural Unemployment Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

1. Definitions

It is an old tradition in labor economics to distinguish between structural, frictional, and cyclical unemployment. Structural unemployment is then envisioned as a result of the institutional set up of the economy, including private and government organizations, types of market arrangements, demography, laws, and regulations. In the literature, the importance of these institutional features for structural unemployment is tied particularly to their implications for demand for and supply of labor, price and wage formation, and the efficacy of search and matching processes in the labor market. Frictional unemployment may be regarded as a subset of structural unemployment, mainly reflecting temporary unemployment spells as the result of job search and matching difficulties in the connection with quits, new entries to the labor market, and job separation because of the employers’ dissatisfaction with individual workers.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Cyclical unemployment differs from structural and frictional unemployment by basically being tied to short-term economic fluctuations. An empirical illustration of the importance of structural unemployment as compared to cyclical is that variations in actually measured unemployment rates have turned out to be much larger between cycles than within cycles, presumably reflecting differences in structural unemployment (Layard et al. 1991). For example, the average unemployment rate over the business cycle in Western Europe has moved from about 3 percent in the mid-1960s to 6 percent in the mid-1970s and to 10 percent from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s. But as pointed out below, various unemployment-persistence mechanisms blur the distinction between cyclical and structural unemployment.

In economic theory, structural and cyclical unemployment usually are regarded as disequilibrium phenomena in the sense that they reflect excess labor supply at existing wages and hence that the labor market does not clear. Then, individual employers informally ration jobs. Nevertheless, technically (analytically) structural unemployment often is analyzed in terms of the concept of equilibrium unemployment. This means that the aggregate-unemployment level is in a ‘state of rest’: existing excess labor supply is assumed to last as long as certain characteristics (parameters) of the economy are unchanged. If this equilibrium is dynamically stable, unemployment equilibrium may also be described as an unemployment level toward which the economy moves as long as new disturbances do not emerge. (The term ‘equilibrium’ is used in several different ways in economics. It refers sometimes to the equality between demand and supply in a market, i.e., to traditional ‘market-clearing,’ in other cases to a state that tends to continue over time regardless of whether the market clears or not. The concept of ‘equilibrium unemployment’ is an example of the latter.)

It is useful to distinguish between two main analytical approaches to equilibrium unemployment: stock approaches and flow approaches. Stock approaches focus on the difference, at a given point in time, between the workforce desired by firms (aggregate stock demand for labor) and the number of workers willing to work (aggregate stock supply of labor). Flow approaches deal with the difference between the flows in and out of the unemployment pool during a certain period. Flow-demand for labor is represented then by the supply of ‘job slots,’ and flow-supply by offers of workers to fill such slots. These two approaches are related because stock demand and stock supply may also be derived in flow approaches. Let us start with stock approaches.

2. Stock Equilibrium

Milton Friedmans’s celebrated ‘natural unemployment rate’ is a stock-equilibrium concept of structural unemployment: ‘the level that would be ground out by the Walrasian system of general equilibrium equations, provided there is imbedded in them the actual structural characteristics of the labor and commodity markets, including market imperfections, stochastic variability in demand and supplies, the costs of gathering information about job vacancies and labor availabilities, the costs of mobility and so on’ (Friedman 1968). Apparently, this concept of equilibrium unemployment covers structural and frictional unemployment as described earlier.

The nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is close to Friedman’s natural rate, though it emphasizes (more than Friedman does) the nonclearing character of the labor market. The NAIRU is defined explicitly as the unemployment rate at which inflation is constant. It is derived from an expectations augmented Phillips curve, i.e., a function that assumes that the price-inflation rate is a decreasing function of the unemployment rate and an increasing function of the expected rate of future inflation (Phelps, 1967). In the simplest possible terms (with linear relations):

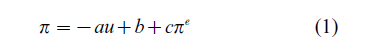

where π is actual inflation, u is the unemployment rate, and πe is expected inflation. For given values of the (positive) parameters a, b, and c, the equation may be depicted as a set of downward sloping short-term Phillips curves (SRi), one curve for each set and for each value of πe (see Fig. 1).

In the context of this model, usually (and realistically) it is assumed that economic agents ask for full compensation for expected inflation in the long run; thus c = 1 in that time perspectives. It is usually also assumed that economic agents do not make systematic expectational errors in the long run; thus π = πe. The only unemployment rate consistent with these two assumptions is, from Equation (1), u* = b/a, where * denotes the equilibrium unemployment rate. It is often also assumed that inflation in this situation is constant over time (and not just that actual and expected inflation coincide), because agents have no reason to revise their price and wage setting behavior when inflation is exactly what they had expected when they formed their decisions. u* is then the NAIRU (the unemployment rate at which inflation is constant), geometrically represented as a vertical long-run Phillips curve, LR in Fig. 1. Inflation increases to the left of that level and falls to the right. Because inflation in this framework in the long run is independent of unemployment, there is no long-run trade-off between these variables. But it has been argued by Lucas (1972) that there is not even a systematic short-term trade-off if economic agents have ‘rational expectations’ (thus, if they never make systematic expectational errors), and if various agents are free to revise their prices and wages in response to changes in expectations. Such a trade-off will then only arise due to random (nonsystematic) expectational errors, e.g., due to random shocks or randomized government policy.

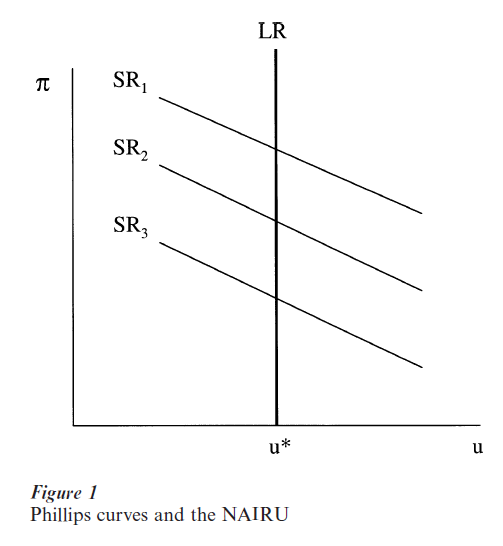

An alternative exposition of stock-equilibrium in the labor market, and hence structural unemployment, gained ground in the 1980s and 1990s; it emphasizes the requirement of consistency of price and wage-setting behavior (Shapiro and Stiglitz, 1984, Layard and Nickell, 1986). Figure 2 gives a simple diagrammatic illustration, with aggregate employment (N) on the horizontal axis and the aggregate real-wage level (w) on the vertical. The LS curve is the traditional aggregate labor supply curve, i.e., the sum of labor supplied by households. The PS curve is the pricesetting curve of firms: for alternative unemployment levels and given nominal wages, the curve defines the price level desired by profit-maximizing firms that operate in imperfectly competitive product markets. Or the PS curve can be described as a labor-demand relation, because it also expresses the combination of employment and real wages desired by profit-maximizing firms. Unemployment is then the horizontal difference between the PS and LS curves.

The WS curve defines wage-setting behavior. It depicts the influence of the (un)employment situation on the real-wage rate that the wage-setting process generates. The intuition is that firms feel compelled to offer higher real wages and that workers and unions demand higher real wages when the labor market is tight (low unemployment) than when it is slack. So by contrast to models with perfectly competitive labor markets, a distinction is made between labor supply (by households) and wage setting (by firms, unions, or more realistically a bargaining process).

The equilibrium real-wage rate is now w0 , equilibrium employment N0 and equilibrium unemployment U0 , the latter being the only unemployment level at which there are no incentives for agents to change prices relative wages and vice versa (corresponding to the equilibrium unemployment rate u* in Fig. 1). This model will be called the PS–WS model of equilibrium (structural) unemployment.

As an illustration, suppose that the real-wage rate in Fig. 2 is initially w0 but that aggregate employment happens to be above N0, e.g., as a result of positive demand shocks to which nominal magnitudes have not yet adjusted. Firms and workers are then dissatisfied with the existing real wage w . Workers and their unions try to raise nominal wages (at existing nominal prices), as can be read off from the WS curve, and firms try to raise prices (at existing nominal wages), as can be read off from the PS curve. The result is a wage-price spiral, as described by the expectation-augmented Phillips-curves model. Firms also start cutting their work force because their desired level is lower than the actual one. Aggregate employment continues to fall until it reaches the unique equilibrium level N0 .The same reasoning, mutatis mutandi, holds if aggregate employment is initially lower than the equilibrium level.

3. Flow Equilibrium

Flow approaches to structural unemployment instead emphasize the flow of workers in and out of un-employment (Phelps 1970, Hall 1979, Diamond 1982). These approaches explicitly grant the heterogeneity of jobs and workers, which means that agents in the labor market must devote time and costs to search to match up idiosyncratic preferences, skills, and skill requirements. In the process, unemployment and vacancies coexist because the latter are not eliminated immediately by the hiring of workers in connection with decentralized negotiations of wages between firms and work applicants.

For simplicity, let us regard the size of the labor force (L) as constant. Further, let s denote the job separation rate, i.e., the fraction of employed workers (N) who lose their jobs in each time period. Let f denote the rate of job finding, i.e., the fraction of unemployed workers (U) who find a job in each time period. We assume that both fractions are constant. The equilibrium unemployment rate (u0) is then defined as a situation when the number of individuals finding jobs equals the number of individuals who are separated from jobs; hence fU = sN. Noting that N = L – U, i.e., that the number of unemployed workers equals the labor force minus the number of employed, we get fU = s(L – U). Rearranging terms and dividing both sides by L, we obtain the equilibrium, or structural, unemployment rate u0 = U / L = s/(s + f ). As expected, the higher the rate of job separation (s), the higher the equilibrium unemployment rate. And the higher the rate of job finding (f )—due to greater intensity and efficiency of job search and hence better job matching—the lower the equilibrium-unemployment rate.

Though the model basically is designed to highlight frictional unemployment, as described earlier, un-employment in the connection with job search and matching may also be due to continuing changes in the composition of demand and supply of different types of workers. This means that flow models of search and job matching also cover elements of what usually is regarded as structural unemployment, which illustrates the previous assertion that frictional unemployment may be regarded as a subset of structural unemployment.

It is natural and feasible to integrate flow and stock approaches to (un)employment determination. For instance, the efficacy of search and matching processes influences the positions of the PS and WS curves in Fig. 2 (and the positions of the Phillips curves in Fig. 1). The longer it takes firms to find the right workers for their vacancies, and the longer it takes work applicants to acquire suitable job offers, the more costly it is to hire workers, and the lower will be the labor-demand curve—the PS curve in Fig. 2. A poorly functioning search and matching process will force recruiting firms to offer higher wages than otherwise; the result is also a higher WS curve. In this way, flow models are related to previously-discussed stock models. Search and matching processes may also be seen as part of the short-term dynamics by which stock equilibrium is reached, with positive gross flows in and out of unemployment, netting to zero when there is flow and stock equilibrium.

4. Microeconomic Foundations

All these macroeconomic models of structural unemployment assume that unemployed workers are not able or willing to get jobs by underbidding the prevailing wages of incumbent workers. The most obvious microeconomic explanation of the absence of wage underbidding is perhaps minimum wage laws. But there seems to be rather general agreement among labor market economists that minimum wages have not been high enough in developed countries to explain much of aggregate structural unemployment in that part of the world. But in some countries, minimum wage laws are binding for specific types of workers, such as inexperienced, unskilled, and physically or mentally handicapped people. (In the special case when a firm has a monopsonistic position in a local labor market minimum wages may, up to a certain wage level, increase rather than reduce employment. In this case, the minimum wage simply prevents the firm from keeping down wage costs by holding back its demand for workers.)

There may also be informal social norms against the underbidding of the wages of incumbent workers. In other words, wage underbidding may not be socially acceptable behavior among workers, and the acceptance of such offers may not be socially acceptable behavior among firms. Legislation may support such norms.

But more elaborate microeconomic foundations of structural unemployment have been developed since the 1980s. In the union monopoly model, unions are assumed to strive for a trade-off between real wages and unemployment. Often, this trade-off is derived formally from a model where unions maximize the expected utility of union members—including those who are employed and those who wind up unemployed due to the union’s wage policy. So labor unions are assumed conscientiously to choose a realwage rate that generates some structural unemployment.

In union-bargaining models, the real wage is instead set in a bilateral bargaining process between a union and a firm or an association of firms. Such models qualitatively yield the same result as the unionmonopoly model, though the real wage will normally be lower and hence the employment level higher, because the firm is assumed to strive for a lower real-wage rate than the union. But neither type of union model answers the questions why there is no underbidding of existing wages by nonorganized workers and why unemployed union members do not leave the union.

There are also theoretical reasons and empirical evidence why the organization of bargaining, such as the degree of coordination and centralization of bargaining, would influence the outcome of the bargaining process and hence also the unemployment level. The most generally accepted hypothesis is probably that both highly centralized and highly decentralized bargaining are more conducive to employment than wage bargaining on levels in between, such as industry-level bargaining (Calmfors and Driffill 1988).

The insider–outsider theory of unemployment emphasizes the asymmetric market powers of incumbent workers, insiders, and disenfranchised workers without jobs in the formal labor market, outsiders (Lindbeck and Snower 1988). Because hiring and firing costs protect incumbent workers, they can push up their wages above the reservation wage of outsiders without losing their jobs. Another way for insiders to prevent wage underbidding is by refusing to cooperate with underbidding outsiders in the production process and by threatening to harass them if underbidding workers are actually hired. With the help of such noncooperation and harassment threats, insiders (possibly with the support of unions) may also be able to create and sustain social norms in their own interest against wage underbidding.

In efficiency wage models, by contrast, the microeconomic foundations of structural unemployment are based on the incentive structure of firms (Yellen 1984). Firms, which are assumed to have all market powers in wage formation, set wages high enough to get a good selection of work applicants and to discourage workers from shirking and quitting. More specifically, firms set wages to balance the cost of higher wages against the productivity increase of having a more efficient work force. Only by accident would the wage level that is optimal for firms clear the labor market.

All these microeconomic theories are rather silent about the employment situation in informal labor markets, where minimum wages are not always respected, unions may not exist, collective bargaining agreements are not binding, efficiency wages are not important, and labor turnover costs are very low and hence insider-outsider mechanisms not important. Extreme examples are sellers of flowers or newspapers on street corners, shoeshine boys, and workers in the underground economy. One conceivable explanation why some workers who are excluded from the formal labor market remain unemployed rather than choose to work in informal labor markets may be an unwillingness to take jobs that are regarded as highly insecure and demeaning. Generous unemployment benefits help them to make this choice. It is significant that informal labor markets are particularly important in countries without unemployment insurance.

In the popular discussion of structural unemployment, it is often believed that labor-saving technological progress and related increases in labor productivity will necessarily result in higher unemployment. Workers are asserted to become redundant because machines replace workers—a vision of technological unemployment as a special variation on structural unemployment. A usual conclusion is that some kind of work sharing is necessary to avoid ever-increasing unemployment. An obvious flaw of this argument is that a gradual rise in productivity will normally be accompanied by higher real wages and profits in the long run, and hence of real income. In this sense, productivity growth creates the foundation for higher demand for output, though deficiencies in aggregate demand may occasionally occur and contribute to recessions. In fact, no long-term trend of the unemployment rate can be detected during the twentieth century.

So work sharing—in the form of a lower general pension age, more generous rules for early retirement, or fewer working hours—is not necessary to prevent gradually rising labor productivity from resulting in rising unemployment. Indeed, the literature in the field clarifies that work sharing is not even likely to contribute to reduced unemployment except in the very short run; one reason is that a reduction of the labor force tends to push up wages. But there is nevertheless a potential problem with continuing productivity growth. Some national economies may fail to adjust to changes in the composition of the demand for labor in the connection with uneven rates of productivity growth among sectors and types of workers (sector shifts or skill shifts in the labor market). This is a respectable explanation as to why unemployment rates among low-skilled workers have increased so much (in percentage points) in Western Europe, where relative wages are quite rigid.

5. Unemployment Persistence

One serious limitation of the concept of unemployment equilibrium as an expression of structural unemployment is that this concept is difficult to distinguish empirically from unemployment persistence, i.e., inertia of unemployment after temporary shocks that have shifted the unemployment rate. Estimated equilibrium rates of unemployment tend to shadow the actual rate, which is an indication of unemployment persistence. Important examples of unemployment persistence are the persistently high unemployment rates after the deflationary policy pursued in several developed countries in the early 1920s and early 1930s; after the oil-price hikes in mid-and late 1970s; and after the restrictive monetary (and in some cases also fiscal) policy in the late 1980s and early 1990s. These experiences raise the suspicion that attempted statistical measurements of equilibrium unemployment also reflect the consequences of various persistence mechanisms. It is hard to find good reasons why the equilibrium unemployment rate in Western Europe should have increased as dramatically as the actual unemployment rate in the 1980s and 1990s.

There are also reasonable microeconomic explanations of unemployment persistence. While some explanations emphasize the behavior of outsiders, others point instead to the behavior of insiders. Examples of persistence mechanisms of the former type are the loss of skill among individuals who have been unemployed for a long time; endogenous changes in preferences in favor of leisure or household work; and the breakdown of social norms in favor of work and hence the emergence of unemployment cultures. We would expect reduced job search in all these cases. Long spells of unemployment may also functions as a negative signal to prospective employers about the quality of individual workers. An example of a persistence mechanism that operates via the behavior of insiders is that they (possibly supported by unions) may exploit subsequent business upswings to push up their wages, hence discouraging firms from expanding their workforce. All this suggests that unemployment persistence is an important factor behind what is usually regarded as structural unemployment. A basic conclusion is that endogenous changes of private behavior after a temporary unemployment-creating shock make the concept of equilibrium unemployment too narrow as a description of structural unemployment. For instance, it is realistic to regard prolonged high unemployment in Western Europe after the mid- 1970s as the combined result of macroeconomic shocks and institutional rigidities that contribute to unemployment persistence. Hence, cyclical unemployment is asserted to have developed into structural unemployment. The result is strong ‘history dependence’ of the unemployment rate. So it is reasonable to widen the concept of structural unemployment to also include unemployment persistence.

6. Policies That Influence Structural Unemployment

Leaving the issue of legislated work sharing aside, what are the influences of government policy on structural unemployment? In the schematic PS–WS model presented earlier, the positions of the PS, WS, and LS curves reflect this influence. The discussion below is confined to taxes, transfer programs, regulations of job-protection, union powers, education training, and other types of active labor market policy.

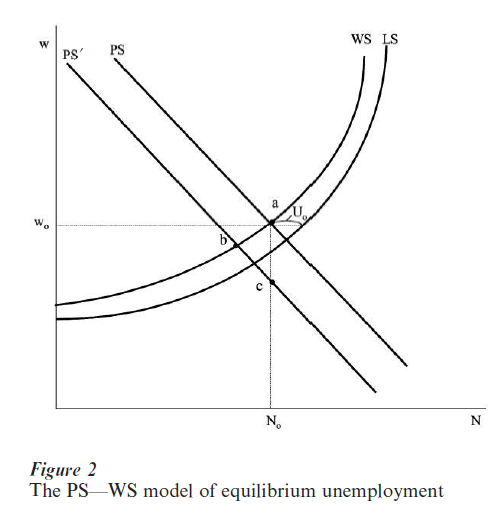

Taxes on labor insert a wedge between the labor costs paid by firms, the product wage (1 + tw)w, and the return to workers, the consumption wage, (1 – ti)w. tw and ti then denote the wage tax (payroll tax), and the income tax. The tax wedge, expressed as the ratio between the product wage and the consumption wedge, is then

A consumption tax would enter the tax wedge in the same way as the wage tax. For example, in terms of Fig. 2, an increase in tw shifts the labor-demand relation (the PS curve) down, e.g., to PS’: at every real-wage rate (w), the demand for labor will be lower than before because the firm must now pay (1 + t+)w for its labor. As long as the WS curve is unchanged, the equilibrium position shifts from point a to point b in the figure, and the equilibrium employment level (N) and the real-wage rate (w) fall. These effects are relevant in the short run. The long-run effects are less obvious, and they depend on the extent to which wage setting adjusts to the tax wedge, which in turn depends on what happens to alternative incomes of workers, such as unemployment benefits and the return on household work. But for low-skilled workers, wages are often tightly regulated, which means that the wage costs for firms are likely to rise and labor demand will fall for this specific group of workers.

The results of empirical studies on these matters are somewhat ambiguous. But on balance, it seems that aggregate employment is negatively affected by wider tax wedges not only in a short and medium-term perspective but also in the long run (Nickell and Layard 1999).

More generous unemployment benefits enable workers to be more selective about offered jobs and hence search for longer time periods—as highlighted by the earlier discussed search approach. Frictional unemployment (or wait unemployment) will then in-crease. Because the income loss in connection with unemployment becomes smaller, firms must offer higher wages to prevent shirking and to keep down quits, as highlighted by efficiency wage models. Moreover, workers and unions become less hesitant to ask for high wages, as emphasized by union and insider– outsider models. This tendency is accentuated by the fact that unemployment benefits are, as a rule, financed by taxes rather than by insurance fees directly tied to specific workers. In terms of Fig. 2, the net effect of all this is that the PS curve is shifted down and the WS curve is shifted up, with rising equilibrium unemployment as a result. Unemployment persistence would also be predicted to increase.

Casual observation and systematic empirical studies, including cross-country regressions, suggest that generous unemployment benefits that may be kept for long periods (in some cases for several years or indefinitely), in fact, have effects of this type (Layard et al. 1991). Other evidence is that the exit rate for individuals from unemployment increases substantially in the US as soon as the benefit period expires after 26 weeks (Katz and Meyer 1990).

Job-security legislation is often singled out as another factor that tends to raise structural unemployment. Basically, such legislation raises the costs of hiring and of firing workers, the former because firms must consider the possibility of future firing costs when hiring workers. Firms will be less anxious to fire workers in recessions but also less interested in hiring workers in business upswings. A predicted effect is that employment tends to be stabilized at the actually existing level whatever this happens to be. In other words, (un)employment persistence would be expected to increase.

Since such legislation increases the market powers of insiders, this helps them to push up their wages. The predicted effect is an increase in the average unemployment rate over the cycle. Moreover, the market power of insiders and unions depends also on other legislation. Important examples are rules that extend the coverage of bargaining agreements to nonunion firms and give large freedom for unions to use conflict weapons, such as the rights to sympathy strikes, secondary actions and blockades, and the right to take out small ‘key groups’ in conflicts.

Most government policies discussed earlier tend to raise structural unemployment (including unemployment persistence). Of course, the other side of the coin is that a reversal of these policies is likely to reduce structural unemployment. But there are also well known examples of government policies directly aiming to lower structural unemployment. Competition policy, which accentuates competition in product markets, induces firms to increase production and employment at given real wages; in terms of Fig. 2, the PS curve shifts to the right. Increased competition in product markets also makes product demand more sensitive to changes in wage costs. This is likely to restrain the wage demands by insiders; the WS curve shifts down. The net effect would be lower equilibrium unemployment.

Active labor market policy is designed to keep workers out of open unemployment in the short term and to subsequently help them to get jobs. In particular, labor-exchange systems and retraining may improve matching between work applicants and vacancies. In terms of Fig. 2, the PS curve shifts up and the WS curve down with falling structural unemployment as a result. Moreover, subsidized education and training that raises labor productivity for (previously) low-skilled workers are likely to raise demand for them and reduce the upward wage pressure for skilled workers. This tends to generate similar shifts in the PS and WS curves as in the case of improved labor market exchanges. Unemployment persistence would also be expected to recede.

On balance, empirical studies suggest that labor-market exchange and properly conduced training programs, in fact, are useful for reducing structural unemployment (Layard et al. 1991); in the short term, also public works programs have such effects. But it is natural that the marginal return falls, possibly to zero, when the programs reach a large size (such as several percent of the labor force), and in particular when the programs are used largely to keep down statistically recorded figures on open unemployment.

Bibliography:

- Calmfors L, Driffill J 1988 Centralized wage bargaining and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy 6: 13–61

- Diamond P 1982 Aggregate demand management in search equilibrium. Journal of Political Economy 90: 881–94

- Friedman M 1968 The role of monetary policy. American Economic Review 58: 1–17

- Hall R E 1979 Theory of the natural unemployment rate and the duration of employment. Journal of Monetary Economy 5: 153–69

- Katz L F, Meyer B D 1990 Unemployment insurance, recall expectations and unemployment outcomes. Quarterly Journal of Economy 105: 973–1002

- Lindbeck A, Snower D J 1988 The Insider–Outsider Theory of Employment and Unemployment. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Layard R, Nickell S 1986 Unemployment in Britain. Economica 53: 121–69

- Layard R, Nickel S, Jackman R 1991 Unemployment: Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Lucas R 1972 Expectations and the neutrality of money. Journal of Economic Theory 4: 103–24

- Nickell S, Layard R 1999 The labour market consequences of technical and structural change. In: Ashenfelter O C, Card D (eds.) Handbook of Labour Economics. North Holland Press, Amsterdam

- Phelps E S 1967 Phillips curves, expectations of inflation and optimal unemployment over time. Economica 34: 254–81

- Phelps E S 1970 (ed.) Microeconomic Foundations of Employment and Inflation Theory. Norton, New York

- Shapiro C, Stiglitz J E 1984 Equilibrium unemployment as a workers disciplinary device. American Economic Review 74: 431–44

- Yellen J 1984 Efficiency wage models of unemployment. American Economic Review 74: 200–5