View sample Situated Cognition Origins Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing services for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Situated cognition encompasses a range of theoretical positions that are united by the assumption that cognition is inherently tied to the social and cultural contexts in which it occurs. This initial definition serves to differentiate situated perspectives on cognition from what Lave (1991) terms the cognition plus view. This latter view follows mainstream cognitive science in characterizing cognition as the internal processing of information. However, proponents of this view also acknowledge that individual cognition is influenced both by the tools and artifacts that people use to accomplish goals and by their ongoing social interactions with others.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

To accommodate these insights, cognition plus theorists analyze the social world as a network of factors that influence individual cognition. Thus, although the cognition plus view expands the conditions that must be taken into account when developing adequate explanations of cognition and learning, it does not reconceptualize the basic nature of cognition. In contrast, situated cognition theorists challenge the assumption that social process can be clearly partitioned off from cognitive processes and treated as external condition for them. These theorists instead view cognition as extending out into the world and as being social through and through. They therefore attempt to break down a distinction that is basic both to mainstream cognitive science and to the cognition plus view, that between the individual reasoner and the world reasoned about.

1. Situation And Context

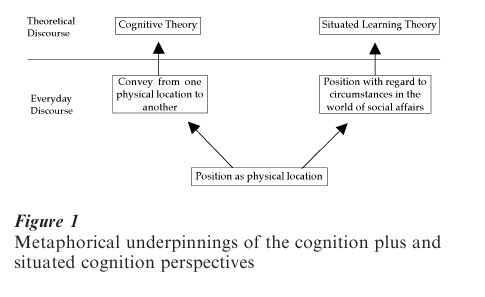

I can further clarify this key difference between the situated and cognition plus viewpoints by focusing on the underlying metaphors that serve to orient adherents to each position as they frame questions and plan investigations. These metaphors are apparent in the different ways that adherents to the two positions use the key terms situation and context (Cobb and Bowers 1999, Sfard 1998). The meaning of these terms in situated theories of cognition can be traced to the notion of position as physical location. In everyday conversation we frequently elaborate this notion metaphorically when we describe ourselves and others as being positioned with respect to circumstances in the world of social affairs. This metaphor is apparent in expressions such as, ‘My situation at work is pretty good at the moment.’ In this and similar examples, the world of social affairs (e.g., work) in which individuals are considered to be situated is the metaphorical correlate of the physical space in which material objects are situated in relation to each other. Situated cognition theorists such as Lave (1988), Saxe (1991), Rogoff (1995), and Cole (1996) elaborate this notion theoretically by introducing the concept of participation in cultural practices (see Fig. 1). Crucially, this core construct of participation is not restricted to face-to-face interactions with others. Instead, all individual actions are viewed as elements or aspects of an encompassing system of cultural practices, and individuals are viewed as participating in cultural practices even when they are in physical isolation from others. Consequently, when situated cognition theorists speak of context, they are referring to a sociocultural context that is defined in terms of participation in a cultural practice.

This view of context is apparent in a number of investigations in which situated cognition theorists have compared mathematical reasoning in school with mathematical reasoning in various out-of-school settings such as grocery shopping (Lave 1988), packing crates in a dairy (Scribner 1984), selling candies on the street (Nunes et al. 1993, Saxe 1991), laying carpet (Masingila 1994), and growing sugar cane (DeAbreu 1995). These studies document significant differences in the forms of mathematical reasoning that arise in the context of different practices that involve the use of different tools and sign systems, and that are organized by different overall motives (e.g., learning mathematics as an end in itself in school vs. doing arithmetical calculations while selling candies on the street in order to survive economically). The findings of these studies have been influential, and challenge the view that mathematics is a universal form of reasoning that is free of the influence of culture.

The underlying metaphor of the cognition plus view also involves the notion of position. However, whereas the core metaphor of situated theories is that of position in the world of social circumstances, the central metaphor of the cognition plus view is that of the transportation of an item from one physical location to another (see Fig. 1). This metaphor supports the characterization of knowledge as an internal cognitive structure that is constructed in one setting and subsequently transferred to other settings in which it is applied. In contrast to this treatment of knowledge as an entity that is acquired in a particular setting, situated cognition theorists are more concerned with knowing as an activity or, in other words, with types of reasoning that emerge as people participate in particular cultural practices.

In line with the transfer metaphor, context, as it is defined by cognition plus theorists, consists of the task an individual is attempting to complete together with others’ actions and available tools and artifacts. Crucially, whereas situated cognition theorists view both tools and others’ actions as integral aspects of an encompassing practice that only have meaning in relation to each other, cognition plus theorists view them as aspects of what might be termed the stimulus environment that is external to internal cognitive processing. Consequently, from this latter perspective, context is under a researcher’s control just as is a subject’s physical location, and can therefore be systematically varied in experiments. Given this conception of context, cognition plus theorists can reasonably argue that cognition is not always tied to context because people do frequently use what they have learned in one setting as they reason in other settings. However, this claim is open to dispute if it is interpreted in terms of situated cognition theory where all activity is viewed as occurring in the context of a cultural practice. Further, situated cognition theorists would dispute the claim that cognition is partly context independent because, from their point of view, an act of reasoning is necessarily an act of participation in a cultural practice.

As an illustration, situated cognition theorists would argue that even a seemingly decontextualized form of reasoning such as research mathematics is situated in that mathematicians use common sign systems as they engage in the communal enterprise of producing results that are judged to be significant by adhering to agreed-upon standards of proof. For situated cognition theorists, mathematicians’ reasoning cannot be adequately understood unless it is located within the context of their research communities. Further, these theorists would argue that to be fully adequate, an explanation of mathematicians’ reasoning has to account for its development or genesis. To address this requirement, it would be necessary to analyze the process of the mathematicians’ induction into their research communities both during their graduate education and during the initial phases of their academic careers.

This illustrative example is paradigmatic in that situated cognition theorists view learning as synonymous with changes in the ways that individuals participate in the practices of communities. In the case of research mathematics, these theorists would argue that mathematicians develop particular ways of reasoning as they become increasingly substantial participants in the practices of particular research communities. They would therefore characterize the mathematicians’ apparently decontextualized reasoning as embedded in these practices and thus as being situated.

2. Vygotsky’s Contribution

Just as situated cognition theorists argue that an adequate analysis of forms of reasoning requires that we understand their genesis, so an adequate account of contemporary situated perspectives requires that we trace their development. All current situated approaches owe a significant intellectual debt to the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who developed his cultural-historical theory of cognitive development in the period of intellectual ferment and social change that followed the Russian revolution. Vygotsky was profoundly influenced by Karl Marx’s argument that it is the making and use of tools that serves to differentiate humans from other animal species. For Vygotsky, human history is the history of artifacts such as language, counting systems, and writing, that are not invented anew by each generation but are instead passed on and constitute the intellectual bequest of one generation to the next. His enduring contribution to psychology was to develop an analogy between the use of physical tools and the use of intellectual tools such as sign systems (Kozulin 1990, van der Veer and Valsiner 1991). He argued that just as the use of a physical tool serves to reorganize activity by making new goals possible, so the use of sign systems serves to reorganize thought. From this perspective, culture can therefore be viewed as a repository of sign systems and other artifacts that are appropriated by children in the course of their intellectual development (Vygotsky 1978). It is important to understand that for Vygotsky, children’s mastery of a counting system does merely enhance or amplify an already existing cognitive capability. Instead, children’s ability to reason numerically is created as they appropriate the counting systems of their culture. This example illustrates Vygotsky’s more general claim that children’s minds are formed as they appropriate sign systems and other artifacts.

Vygotsky refined his thesis that children’s cognitive development is situated with respect to the sign systems of their culture as he pursued several related lines of empirical inquiry. In his best known series of investigations, he attempted to demonstrate the crucial role of face-to-face interactions in which an adult or more knowledgeable peer supports the child’s use of an intellectual tool such as a counting system (Vygotsky 1962). For example, one of the child’s parents might engage the child in a play activity in the course of which parent and child count together. Vygotsky interpreted observations of such interactions as evidence that the use of sign systems initially appears in children’s cognitive development on what he termed the ‘intermental plane of social interaction.’ He further observed that over time the adult gradually reduces the level of support until the child can eventually carry out what was previously a joint activity on his or her own. This observation supported his claim that the child’s mind is created via a process of internalization from the intermental plane of social interaction to the intramental plane of individual thought.

A number of Western psychologists revived this line of work in the 1970s and 1980s by investigating how adults support or scaffold children’s learning as they interact with them. However, in focusing almost exclusively on the moves or strategies of the adult in supporting the child, they tended to portray learning as a relatively passive process. This conflicts with the active role that Vygotsky attributed to the child in constructing what he referred to as the ’higher mental functions’ such as reflective thought. In addition, these turn-by-turn analyses of adult–child interactions typically overlooked the broader theoretical orientation that informed Vygotsky’s investigations. In focusing on social interaction, he attempted to demonstrate both that the environment in which the child learns is socially organized and that it is the primary determinant of the forms of thinking that the child develops. He therefore rejected descriptions of the child’s learning environment that are cast in terms of absolute indices because such a characterization defines the environment in isolation from the child. He argued that the analyses should instead focus on what the environment means to the child. This, for him, involved analyzing the social situations in which the child participates and the cognitive processes that the child develops in the course of that participation.

Thus far, in discussing Vygotsky’s work, I have emphasized the central role that he attributed to social interactions with more knowledgeable others. There is some indication that shortly before his death in 1934 at the age of 36, he was beginning to view the relation between social interaction and cognitive development as a special case of a more general relation between cultural practices and cognitive development (Davydov and Radzikhovskii 1985, Minick 1987). In doing so he came to see face-to-face interactions as located within an encompassing system of cultural practices. For example, he argued that it is not until children participate in the activities of formal schooling that they develop what he termed scientific concepts. In making this claim, he viewed classroom interactions between a teacher and his or her students as an aspect of the organized system of cultural practices that constituted formal schooling in the USSR at that time. A group of Soviet psychologists, the most prominent of whom was Alexei Leont’ev, developed this aspect of cultural-historical theory more fully after Vygotsky’s death.

3. Leont’ev’s Contribution

Two aspects of Leont’ev’s work are particularly significant from the vantage point of contemporary situated perspectives. The first concerns his clarification of an appropriate unit of analysis when accounting for intellectual development. Although face-to-face interactions constitute the immediate social situation of the child’s development, Leont’ev saw the encompassing cultural practices in which the child participates as constituting the broader context of his or her development (Leont’ev 1978, 1981). For example, Leont’ev might have viewed an interaction in which a parent engages a child in activities that involve counting as an instance of the child’s initial, supported participation in cultural practices that involve dealing with quantities. Further, he argued that children’s progressive participation in specific cultural practices underlies the development of their thinking. Intellectual development was, for him, synonymous with the process by which the child becomes a full participant in particular cultural practices. In other words, he viewed the development of children’s minds and their increasingly substantial participation in various cultural practices as two aspects of a single process. This is a strongly situated position in that the cognitive capabilities that children develop are not seen as distinct from the cultural practices that constitute the context of their development. From this perspective, the cognitive characteristics a child develops are characteristics of the child-in-cultural-practice in that they cannot be defined apart from the practices that constitute the child’s world. For Leont’ev, this implied that the appropriate unit of analysis is the child-inculture-practice rather than the child per se. As stated earlier, it is this rejection of the individual as a unit of analysis that separates contemporary situated perspectives from what I called the cognition plus viewpoint.

Leont’ev’s second important contribution concerns his analysis of the external world of material objects and events. Although Vygotsky brought sign systems and other cultural tools to the fore, he largely ignored material reality. In building on the legacy of his mentor, Leont’ev argued that material objects as they come to be experienced by developing children are defined by the cultural practices in which they participate. For example, a pen becomes a writing instrument rather than a brute material object for the child as he or she participates in literacy practices. In Leont’ev’s view, children do not come into contact with material reality directly, but are instead oriented to this reality as they participate in cultural practices. He therefore concluded that the meanings that material objects come to have are a product of their inclusion in specific practices. This in turn implied that these meanings cannot be defined independently of the practices. This thesis only served to underscore his argument that the individual-cultural-practice constitutes the appropriate analytical unit for psychology.

Bibliography:

- Cobb P, Bowers J 1999 Cognitive and situated perspectives in theory and practice. Educational Researcher 28(2): 4–15

- Cole M 1996 Cultural Psychology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Davydov V V, Radzikhovskii L A 1985 Vygotsky’s theory and the activity-oriented approach in psychology. In: Wertsch J V (ed.) Culture, Communication, and Cognition: Vygotskian Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 35–65

- DeAbreu G 1995 Understanding how children experience the relationship between home and school mathematics. Mind, Culture, and Activity 2: 119–42

- Kozulin A 1990 Vygotsky’s Psychology: A Biography of Ideas. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Lave J 1988 Cognition in Practice: Mind, Mathematics, and Culture in Everyday Life. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Lave J 1991 Situating learning in communities of practice. In: Resnick L B, Levine J M, Teasley S D (eds.) Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp. 63–82

- Leont’ev A N 1978 Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Leont’ev A N 1981 The problem of activity in psychology. In: Wertsch J V (ed.) The Concept of Activity in Soviet Psychology. Sharpe, Armonk, NY, pp. 37–71

- Masingila J O 1994 Mathematics practice in carpet laying. Anthropology and Education Quarterly 25: 430–62

- Minick N 1987 The development of Vygotsky’s thought: An introduction. In: Rieber R W, Carton A S (eds.) The Collected Works of Vygotsky, L.S. (Vol. 1): Problems of General Psychology. Plenum, New York, pp. 17–38

- Nunes T, Schliemann A D, Carraher D W 1993 Street Mathematics and School Mathematics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

- Rogoff B 1995 Observing sociocultural activity on three planes: Participatory appropriation, guided participation, and apprenticeship. In: Wertsch J V, del Rio P, Alvarez A (eds.) Sociocultural Studies of Mind. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 139–64

- Saxe G B 1991 Culture and Cognitive Development: Studies in Mathematical Understanding. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Scribner S 1984 Studying working intelligence. In: Rogoff B, Lave J (eds.) E eryday Cognition: Its Development in Social Context. Harvard Univesity Press, Cambridge, pp. 9–40

- Sfard A 1998 On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one. Educational Research 27(21): 4–13

- van der Veer R, Valsiner J 1991 Understanding Vygotsky: A Quest for Synthesis. Blackwell, Cambridge, MA

- Vygotsky L S 1962 Thought and Language. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Vygotsky L S 1978 Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA