View sample Self-Development In Childhood Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In addition to domain-specific self-concepts, the ability to evaluate one’s overall worth as a person emerges in middle childhood. The level of such global self-esteem varies tremendously across children and is determined by how adequate they feel in domains of importance as well as the extent to which significant others (e.g., parents and peers) approve of them as a person. Efforts to promote positive self-esteem are critical, given that low self-esteem is associated with many psychological liabilities including depressed affect, lack of energy, and hopelessness about the future.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Introduction

Beginning in the second year of life toddlers begin to talk about themselves. With development, they come to understand that they possess various characteristics, some of which may be positive (‘I’m smart’) and some of which may be negative (‘I’m unpopular’). Of particular interest is how the very nature of such self-evaluations changes with development as well as among individual children and adolescents across two basic evaluative categories, (a) domain-specific self-concepts, i.e., how one judges one’s attributes in particular arenas, e.g., scholastic competence, social (for a complete treatment of self-development in childhood and adolescence, see Harter 1999).

Developmental shifts in the nature of self-evaluations are driven by changes in the child’s cognitive capabilities. Cognitive developmental theory and findings (see Piaget 1960, 1963, Fischer 1980) alert us to the fact that the young child is limited to very specific, concrete representations of self and others, for example, ‘I know my ABCs’ (see Harter 1999). In middle to later childhood, the ability to form higher-order concepts about one’s attributes and abilities (e.g., ‘I’m smart’) emerges. There are further cognitive advances at adolescence, allowing the teenager to form abstract concepts about the self that transcend concrete behavioral manifestations and higher-order generalizations (e.g., ‘I’m intelligent’).

2. Developmental Differences In Domain-Specific Self-Concepts

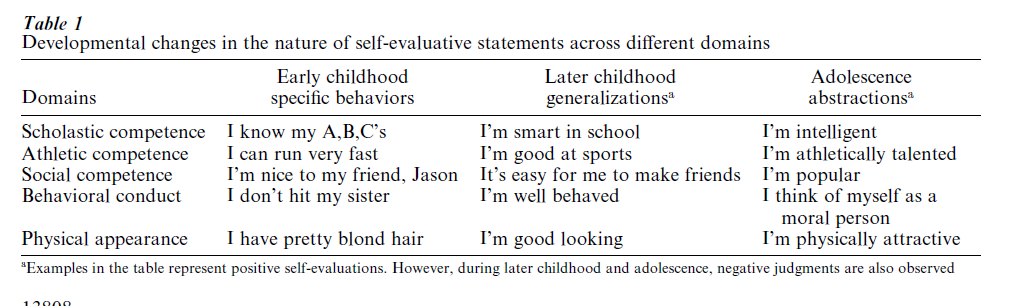

Domain-specific evaluative judgments are observed at every developmental level. However, the precise nature of these judgments varies with age (see Table 1). In Table 1, five common domains in which children and adolescents make evaluate judgments about the self are identified: Scholastic competence, Physical competence, Social competence, Behavioral conduct, and Physical appearance. The types of statements vary, however, across three age periods, early childhood, later childhood, and adolescence, in keeping with the cognitive abilities of each age period.

2.1 Early Childhood

Young children provide very concrete accounts of their capabilities, evaluating specific behaviors. Thus, they communicate how they know their ABCs, how they can run very fast, how they are nice to a particular friend, how they don’t hit their sister, and how they possess a specific physical feature such as pretty blond hair. Of particular interest in such accounts is the fact that the young child typically provides a litany of virtues, touting his or her positive skills and attributes. One cognitive limitation of this age period is that the young child cannot distinguish the wish to be competent from reality. As a result, they typically overestimate their abilities because they do not yet have the skills to evaluate themselves realistically. Another cognitive characteristic that contributes to potential distortions is the pervasiveness of all-or-none thinking. That is, evaluations are either all positive or all negative. With regard to self-evaluations, they are typically all positive. (Exceptions to this positivity bias can be observed in children who are chronically abused, since severe maltreatment is often accompanied by parental messages that make the child feel inadequate, incompetent, and unlovable. Such children will also engage in all-or-none thinking but conclude that they are all bad.)

2.2 Middle To Later Childhood

As the child grows older, the ability to make higher-order generalizations in evaluating his or her abilities and attributes emerges. Thus, rather than cite prowess at a particular activity, the child may observe that he or she is good at sports, in general. This inference can further be justified in that the child can describe his or her talent at several sports (e.g., good at soccer, basketball, baseball). Thus, the higher-order generalization represents a cognitive construction in which an over-arching judgment (good at sports) is defined in terms of specific examples which warrant this conclusion. Similar processes allow the older child to conclude that he or she is smart (e.g., does well in math, science, and history). The structure of a higher-order generalization about being well behaved could include such components as obeying parents, not getting in trouble, and trying to do what is right. A generalization concerning the ability to make friends may subsume accounts of having friends at school, making friends easily at camp, and developing friendships readily upon moving to a new neighborhood. The perception that one is good-looking may be based on one’s positive evaluation of one’s face, hair, and body.

During middle childhood, all-or-none thinking diminishes and the aura of positivity fades. Thus, children do not typically think that they are all virtuous in every domain. The more common pattern is for them to feel more adequate in some domains than others. For example, one child may feel that he or she is good at schoolwork and is well behaved, whereas he or she is not that good at sports, does not think that he or she is good-looking, and reports that it is hard to make friends. Another child may report the opposite pattern.

Table 1 Developmental changes in the nature of self-evaluative statements across different domains

There are numerous combinations of positive and negative evaluations across these domains that children can and do report. Moreover, they may report both positive and negative judgments within a given domain, for example, they are smart in some school subjects (math and science) but ‘dumb’ in others (english and social studies). Such evaluations may also be accompanied by self-affects that also emerge in later childhood, for example, feeling proud of one’s accomplishments but ashamed of one’s perceived failures. This ability to consider both positive and negative characteristics is a major cognitive–developmental acquisition. Thus, beginning in middle to later childhood, these distinctions result in a profile of self-evaluations across domains.

Contributing to this advance is the ability to engage in social comparison. Beginning in middle childhood one can use comparisons with others as a barometer of the skills and attributes of the self. In contrast, the young child cannot simultaneously compare his or her attributes to the characteristics of another in order to detect similarities or differences that have implications for the self. Although the ability to utilize social comparison information for the purpose of self-evaluation represents a cognitive-developmental advance, it also ushers in new, potential liabilities. With the emergence of the ability to rank-order the performance of other children, all but the most capable children will necessarily fall short of excellence. Thus, the very ability and penchant to compare the self with others makes one’s self-concept vulnerable, particularly if one does not measure up in domains that are highly valued. The more general effects of social comparison can be observed in findings revealing that domain-specific self-concepts become more negative during middle and later childhood, compared to early childhood.

2.3 Adolescence

For the adolescent, there are further cognitive developmental advances that alter the nature of domain-specific self-evaluations. As noted earlier, adolescence brings with it the ability to create more abstract judgments about one’s attributes and abilities. Thus, one no longer merely considers oneself to be good at sports but to be athletically talented. One is no longer merely smart but views the self more generally as intelligent, where successful academic performance, general problem-solving ability, and creativity might all be subsumed under the abstraction of intelligence. Abstractions may be similarly constructed in the other domains. For example, in the domain of behavioral conduct, there will be a shift from the perception that one is well behaved to a sense that one is a moral or principled person. In the domains of social competence and appearance, abstractions may take the form of perceptions that one is popular and physically attractive.

These illustrative examples all represent positive self-evaluations. However, during adolescence (as well as in later childhood), judgments about one’s attributes will also involve negative self-evaluations. Thus, certain individuals may judge the self to be unattractive, unpopular, unprincipled, etc. Of particular interest is the fact that when abstractions emerge, the adolescent typically does not have total control over these new acquisitions, just as when one is acquiring a new athletic skill (e.g., swinging a bat, maneuvering skis), one lacks a certain level of control. In the cognitive realm, such lack of control often leads to overgeneralizations that can shift dramatically across situations or time. For example, the adolescent may conclude at one point in time that he or she is exceedingly popular but then, in the face of a minor social rebuff, may conclude that he or she is extremely unpopular. Gradually, adolescents gain control over these self-relevant abstractions such that they become capable of more balanced and accurate self-representations (see Harter 1999).

3. Global Self-Esteem

The ability to evaluate one’s worth as a person also undergoes developmental change. The young child simply is incapable, cognitively, of developing the verbal concept of his/her value as a person. This ability emerges at the approximate age of eight. However, young children exude a sense of value or worth in their behavior. The primary behavioral manifestations involve displays of confidence, independence, mastery attempts, and exploration (see Harter 1999). Thus, behaviors that communicate to others that children are sure of themselves are manifestations of high self-esteem in early childhood.

At about the third grade, children begin to develop the concept that they like, or don’t like, the kind of person they are (Harter 1999, Rosenberg 1979). Thus, they can respond to general items asking them to rate the extent to which they are pleased with themselves, like who they are, and think they are fine, as a person. Here, the shift reflects the emergence of an ability to construct a higher-order generalization about the self. This type of concept can be built upon perceptions that one has a number of specific qualities; for example, that one is competent, well behaved, attractive, etc. (namely, the type of domain-specific self-evaluations identified in Table 1). It can also be built upon the observation that significant others, for example, parents, peers, teachers, think highly of the self. This process is greatly influenced by advances in the child’s ability to take the perspective of significant others (Selman 1980). During adolescence, one’s evaluation of one’s global worth as a person may be further elaborated, drawing upon more domains and sources of approval, and will also become more abstract. Thus, adolescents can directly acknowledge that they have high or low self-esteem, as a general abstraction about the self.

4. Individual Differences In Domain-Specific Self-Concepts As Well As Global Self-Esteem

Although there are predictable cognitively based developmental changes in the nature of how most children and adolescents describe and evaluate themselves, there are striking individual differences in how positively or negatively the self is evaluated. Moreover, one observes different profiles of children’s perceptions of their competence or adequacy across the various self-concept domains, in that children evaluate themselves differently across domains. Consider the profiles of four different children. One child, Child A, may feel very good about her scholastic performance, although this is in sharp contrast to her opinion of her athletic ability, where she evaluates herself quite poorly. Socially she feels reasonably well accepted by her peers. In addition, she considers herself to be well behaved. Her feelings about her appearance, however, are relatively negative. Child A also reports very high self-esteem. Another child, Child B, has a very different configuration of scores. This is a boy who feels very incompetent when it comes to schoolwork. However, he considers himself to be very competent, athletically, and feels well received by peers. He judges his behavioral conduct to be less commendable. In contrast, he thinks he is relatively good-looking. Like Child A, he also reports high self-esteem.

Other profiles are exemplified by Child C and Child D, neither of whom feel good about themselves scholastically or athletically. They evaluate themselves much more positively in the domains of social acceptance, conduct, and physical appearance. In fact, their profiles are quite similar to each other across the five specific domains. However, judgments of their self-esteem are extremely different. Child C has very high self-esteem whereas Child D has very low self-esteem. This raises a puzzling question: how can two children look so similar with regard to their domainspecific self-concepts but evaluate their global self-esteem so differently? We turn to this issue next, in examining the causes of global self-esteem.

5. The Causes Of Children’s Level Of Self-Esteem

Our understanding of the antecedents of global self-esteem have been greatly aided by the formulations of two historical scholars of the self, William James (1892) and Charles Horton Cooley (1902). Each suggested rather different pathways to self-esteem, defined as an overall evaluation of one’s worth as a person (see reviews by Harter 1999, Rosenberg 1979). James focused on how the individual assessed his or her competence in domains where one had aspirations to succeed. Cooley focused on the salience of the opinions that others held about the self, opinions which one incorporated into one’s global sense of self.

5.1 Competence–Adequacy In Domains Of Importance

For James, global self-esteem derived from the evaluations of one’s sense of competence or adequacy in the various domains of one’s life relative to how important it was to be successful in these domains. Thus, if one feels one is successful in domains deemed important, high self-esteem will result. Conversely, if one falls short of one’s goal in domains where one has aspirations to be successful, one will experience low self-esteem. One does not, therefore, have to be a superstar in every domain to have high self-esteem. Rather, one only needs to feel adequate or competent in those areas judged to be important. Thus, a child may evaluate himself or herself as unathletic; however, if athletic prowess is not an aspiration, then self-esteem will not be negatively affected. That is, the high self-esteem individual can discount the importance of areas in which one does not feel successful.

This analysis can be applied to the profiles of Child C and Child D. In fact, we have directly examined this explanation in research studies by asking children to rate how important it is for them to be successful (Harter 1999). The findings reveal that high self-esteem individuals feel competent in domains they rate as important. Low self-esteem individuals report that areas in which they are unsuccessful are still very important to them. Thus, Child C represents an example of an individual who feels that social acceptance, conduct, and appearance, domains in which she evaluates herself positively, are very important but that the two domains where she is less successful, scholastic competence and athletic competence are not that important. In contrast, Child D rates all domains as important, including the two domains where he is not successful; scholastic competence and athletic competence. Thus, the discrepancy between high importance coupled with perceptions of inadequacy contribute to low self-esteem.

5.2 Incorporation Of The Opinions Of Significant Others

Another important factor influencing self-esteem can be derived from the writings of Cooley (1902) who metaphorically made reference to the ‘looking-glass self’ (see Oosterwegel and Oppenheimer 1993). According to this formulation, significant others (e.g., parents and peers) were social mirrors into which one gazed in order to determine what they thought of the self. Thus, in evaluating the self, one would adopt what one felt were the judgments of these others whose opinions were considered important. Thus, the approval, support, or positive regard from significant others became a critical source of one’s own sense of worth as a person. For example, children who receive approval from parents and peers will report much higher self-esteem than children who experience disapproval from parents and peers.

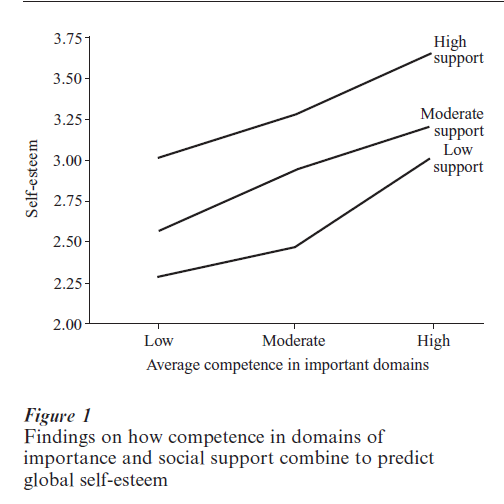

Findings reveal that both of these factors, competence in domains of importance and the perceived support of significant others, combine to influence a child’s or adolescent’s self-esteem. Thus, as can be observed in Fig. 1, those who feel competent in domains of importance and who also report high support, rate themselves as having the highest self-esteem. Those who feel inadequate in domains deemed important and who also report low levels of support, rate themselves as having the lowest self-esteem. Other combinations fall in between (data from Harter 1993).

6. Conclusions

Two types of self-representations that can be observed in children and adolescents were distinguished, evaluative judgments of competence or adequacy in specific domains and the global evaluation of one’s worth as a person, namely overall self-esteem. Each of these undergoes developmental change based on agerelated cognitive advances. In addition, older children and adolescents vary tremendously with regard to whether self-evaluations are positive or negative. Within a given individual, there will be a profile of self-evaluations, some of which are more positive and some more negative. More positive self-concepts in domains considered important, as well as approval from significant others, will lead to high self-esteem. Conversely, negative self-concepts in domains considered important, coupled with lack of approval from significant others, will result in low self-esteem. Self-esteem is particularly important since it is associated with very important outcomes or consequences. Perhaps the most well-documented consequence of low self-esteem is depression. Children and adolescents (as well as adults) with the constellation of causes leading to low self-esteem will invariably report that they feel depressed, emotionally, and are hopeless about their futures; the most seriously depressed consider suicide. Thus, it is critical that we intervene for those experiencing low self-esteem. Our model of the causes of self-esteem suggests strategies that may be fruitful, for example, improving skills, helping individuals discount the importance of domains in which it is unlikely that they can improve, and providing support in the form of approval for who they are as people. Future research, however, is necessary to determine the different pathways to low and high self-esteem. For example, for one child, the sense of inadequacy in particular domains may be the pathway to low self-esteem. For another child, lack of support from parents or peers may represent the primary cause. Future efforts should be directed to the identification of these different pathways since they have critical implications for intervention efforts to enhance feelings of worth for those children with low self-esteem. Positive self-esteem is clearly a psychological commodity, a resource that is important for us to foster in our children and adolescents if we want them to lead productive and happy lives.

Bibliography:

- Cooley C H 1902 Human Nature and the Social Order. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York

- Damon W, Hart D 1988 Self-understanding in Childhood and Adolescence. Cambridge University Press, New York

- Fischer K W 1980 A theory of cognitive development: the control and construction of hierarchies of skills. Psychological Review 87: 477–531

- Harter S 1993 Causes and consequences of low self-esteem in children and adolescents. In: Baumeister R F (ed.) Self-esteem: The Puzzle of Low Self-regard. Plenum, New York

- Harter S 1999 The Construction of the Self: A Developmental Perspective. Guilford Press, New York

- James W 1892 Psychology: The Briefer Course. Henry Holt, New York

- Oosterwegel A, Oppenheimer L 1993 The Self-system: Developmental Changes Between and Within Self-concepts. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

- Piaget J 1960 The Psychology of Intelligence. Littlefield, Adams, Patterson, NJ

- Piaget J 1963 The Origins of Intelligence in Children. Norton, New York

- Rosenberg M 1979 Conceiving the Self. Basic Books, New York

- Selman R L 1980 The Growth of Interpersonal Understanding. Academic Press, New York