View sample School Achievement Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Although the analysis of school achievement (SA)—its structure, determinants, correlates, and consequences—has always been a major issue of educational psychology, interest in achievement as a central outcome of schooling has considerably increased during the last decade. In particular, large-scale projects like TIMSS (Third International Mathematics and Science Study) (Beaton et al. 1996) had a strong and enduring impact on educational policy as well as on educational research and have also raised the public interest in scholastic achievement.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. School Achievement And Its Determinants: An Overview

SA can be characterized as cognitive learning outcomes which are products of instruction or aimed at by instruction within a school context. Cognitive outcomes mainly comprise procedural and declarative knowledge but also problem-solving skills and strategies. The following facets, features, and dimensions of SA, most of which are self-explaining, can be distinguished:

(a) episodic vs. cumulative;

(b) general/global vs. domain-specific;

(c) referring to different parts of a given subject (in a foreign language e.g., spelling, reading, writing, communicating, or from the competency perspective, grammatical, lexical, phonological, and orthographical);

(d) test-based vs. teacher-rated;

(e) performance-related vs. competence-related;

(f) actual versus potential (what one could achieve, given optimal support);

(g) different levels of aggregation (school, class- room, individual level);

(h) curriculum-based vs. cross-curricular or extra- curricular.

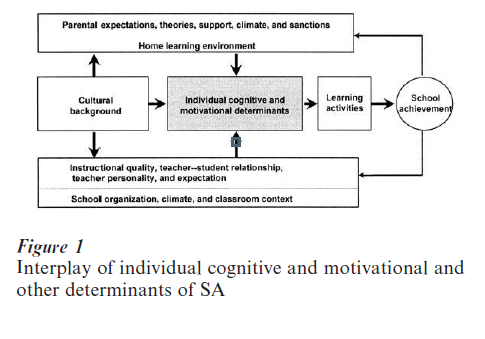

Figure 1 shows a theoretical model that represents central determinants of SA. Cognitive and motivational determinants are embedded in a complex system of individual, parental, and school-related determinants and depend on the given social, class- room, and cultural context. According to this model, cognitive and motivational aptitudes have a direct impact on learning and SA, whereas the impact of the other determinants in the model on SA is only indirect.

2. Cognitive Determinants

2.1 Intelligence

Intelligence is certainly one of the most important determinants of SA. Most definitions of intelligence refer to abstract thinking, ability to learn, and problem solving, and emphasize the ability to adapt to novel situations and tasks. There are different theoretical perspectives, for example Piagetian and neo-Piagetian approaches, information-processing approaches, component models, contextual approaches, and newer integrative conceptions such as Sternberg’s triarchic theory of intelligence, or Gardner’s model of multiple intelligences. Among them, the traditional psychometric approach is the basis for the study of individual differences. In this approach quantitative test scores are analyzed by statistical methods such as factor analysis to identify dimensions or factors underlying test performance (Sternberg and Kaufman 1998). Several factor theories have been proposed ranging from a general-factor model to various multiple-factor models. One of the most significant contributions has been a hierarchical model based on second-order factors that distinguishes between fluid and crystallized abilities. Fluid intelligence refers to basic knowledge-free information-processing capacity such as detecting relations within figural material, whereas crystallized intelligence reflects influences of acculturation such as verbal knowledge and learned strategies. Fluid and crystallized abilities can both be seen as representing general intelligence as some versions of a complete hierarchical model would suggest (see Gustafsson and Undheim 1996).

Substantial correlations (the size of the correlations differ from r = 0.50 to r = 0.60) between general intelligence and SA have been reported in many studies. That is, more than 25 percent of variance in post-test scores are accounted for by intelligence, depending on student age, achievement criteria, or time interval between measurement of intelligence and SA. General intelligence, especially fluid reasoning abilities, can be seen as a measure of flexible adaptation of strategies in novel situations and complex tasks which put heavy demands and processing loads on problem solvers.

The close correlation between intelligence and SA has formed the basis for the popular paradigm of underachievement and overachievement: Students whose academic achievement performance is lower than predicted on the basis of their level of intelligence are characterized as underachievers; in the reverse case as overachievers. This concept, however, has been criticized as it focuses on intelligence as the sole predictor of SA although SA is obviously determined by many other individual as well as instructional variables.

Intelligence is related to quality of instruction. Low instructional quality forces students to fill in gaps for themselves, detect relations, infer key concepts, and develop their own strategies. On the whole, more intelligent students are able to recognize solutionrelevant rules and to solve problems more quickly and more efficiently. Additionally, it is just that ability that helps them to acquire a rich knowledge base which is ‘more intelligently’ organized and more flexibly utilizable and so has an important impact on following learning processes. Accordingly, intelligence is often more or less equated with learning ability (see Gustafsson and Undheim 1996).

Beyond general intelligence, specific cognitive abilities do not seem to have much differential predictive power, although there is occasional evidence for a separate contribution of specific abilities (Gustafsson and Undheim 1996). In Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences there are seven abilities (logicalmathematical, linguistic, spatial, musical, bodilykinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal intelligence). Among domain-specific abilities, reading ability that is related to linguistic intelligence in Gardner’s model, has some special significance. Specific abilities such as phonological awareness have turned out as early predictors of reading achievement.

2.2 Learning Styles And Learning Strategies

Styles refer to characteristic modes of thinking that develop in combination with personality factors. While general cognitive or information-processing styles are important constructs within differential psychology, learning styles are considered as determinants of SA. Learning styles are general approaches toward learning; they represent combinations of broad motivational orientations and preferences for strategic processing in learning. Prominent learning style conceptions mainly differ with respect to intrinsic and extrinsic goal orientations and surface processing vs. deep processing. Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation deals with whether task fulfillment is a goal of its own or a means for superordinate goals. In deep processing, learners try to reach a comprehension of tasks as complete as possible to incorporate their representations into their own knowledge structures and give them personal significance. In surface processing, learners confine processing to the point where they can reproduce the material in an examination or achievement situation as well as possible (Snow et al. 1996).

Compared to general learning styles, learning strategies are more specific: They represent goal-oriented endeavors to influence one’s own learning behavior. While former research mostly dealt with simple study skills that were seen as observable behavioral techniques, now cognitive and metacognitive strategies are included. Learning strategies therefore comprise cognitive strategies (rehearsal, organization, elaboration) and metacognitive strategies (planning, monitoring, regulation) as well as resource-oriented strategies (creating a favorable learning environment, controlling attention, and sustaining concentration) (Snow and Swanson 1992). Frequently, learning strategies are assessed by means of questionnaires.

In spite of the great importance learning strategies have for understanding knowledge acquisition and learning from instruction, only few empirical data concerning the relation between learning strategies and SA are available. Most studies done in the context of schools and universities have shown positive but small correlations between learning strategies and SA. One reason may be that assessment by questionnaires is too general. On the whole, the exact conditions under which learning strategies are predictive to achievement have still to be worked out.

Besides motivational and metacognitive factors, epistemological beliefs are important determinants for learning strategies and achievement. They refer to beliefs about the nature of knowledge and learning such as: knowledge acquisition depends on innate abilities, knowledge is simple and unambiguous, and learning is quick. Epistemological beliefs can influence quality of achievement and persistence on difficult tasks (Schommer 1994).

2.3 Prior Knowledge

Although there have been early attempts to identify knowledge prerequisites for learning, the role of prior knowledge as a determinant of SA has long been neglected. Since the early 1980s, research on expertise has convincingly demonstrated that superior performance of experts is mainly caused by the greater quantity and quality of their knowledge bases. Prior knowledge does not only comprise domain-specific content knowledge, that is, declarative, procedural, and strategic knowledge, but also metacognitive knowledge, and it refers to explicit knowledge as well as to tacit knowledge (Dochy 1992). Recent research has shown that taskspecific and domain-specific prior knowledge often has a higher predictive power for SA than intelligence: 30 to 60 percent of variance in post-test scores is accounted for by prior knowledge (Dochy 1992, Weinert and Helmke 1998). Further results concern the joint effects of intelligence and prior knowledge on SA. First, there is a considerable degree of overlap in the predictive value of intelligence and prior knowledge for SA. Second, lack of domain-specific knowledge cannot be compensated for by intelligence (Helmke and Weinert 1999).

But learning is not only hindered by a lack of prior knowledge, but also by misconceptions many learners have acquired in their interactions with everyday problems. For example, students often have naïve convictions about physical phenomena that contradict fundamental principles like conservation of motion. These misconceptions, which are deeply rooted in people’s naive views of the world, often are in conflict with new knowledge to be acquired by instruction. To prevent and overcome these conflicts and to initiate processes of conceptual change is an important challenge for classroom instruction.

3. Motivational Determinants

3.1 Self-Concept Of Ability

The self-concept of ability (largely equivalent with subjective competence, achievement-related self-confidence, expectation of success, self-efficacy; see Self-concepts: Educational Aspects; Self-efficacy: Educational Aspects) represents the expectancy component within the framework of an expectancy x value approach, according to which subjective competence (expectancy aspect) and subjective importance (value aspect) are central components of motivation. Substantial correlations between self-concept of ability and SA have been found. Correlations are the higher, the more domain-specific the self-concept of ability is conceptualized, the higher it is, and the older the pupils are. Self-concept of ability is negatively related to test anxiety and influences scholastic performance by means of various mechanisms: Students with a high self-concept of ability (a) initiate learning activities more easily and quickly and tend less to procrastination behavior, (b) are more apt to continue learning and achievement activities in difficult situations (e.g., when a task is unexpectedly difficult), (c) show more persistence, (d) are better protected against interfering cognitions such as self-doubt and other worries (Helmke and Weinert 1997).

3.2 Attitude Towards Learning, Motivation To Learn, And Learning Interest

There are several strongly interrelated concepts that are associated with the subjective value—of the domain or subject under consideration, of the respective activities, or on a more generalized level, of teachers and school. The value can refer to the affective aspect of an attitude, to subjective utility, relevance, or salience. In particular, attitude toward learning means the affective (negative or positive) aspect of the orientation towards learning; interest is a central element of self-determined action and a component of intrinsic motivation, and motivation to learn comprises subjective expectations as well as incentive values (besides anticipated consequences like pride, sorrow, shame, or reactions of significant others, the incentive of learning action itself, i.e., interest in activity). Correlations between SA and those constructs are found to be positive but not very strong (the most powerful is interest with correlations in the range of r 0.40). These modest relations indicate that the causal path from interest, etc. to SA is far and complex and that various mediation processes and context variables must be taken into account (Helmke and Weinert 1997).

3.3 Volitional Determinants

Motivation is a necessary but often not sufficient condition for the initiation of learning and for SA. To understand why some people—in spite of sufficient motivation—fail to transform their learning intentions into correspondent learning behavior, volitional concepts have proven to be helpful. Recent research on volition has focused on forms of action control, especially the ability to protect learning intentions against competitive tendencies, using concepts like ‘action vs. state orientation’ (Kuhl 1992). The few empirical studies that have correlated volitional factors with SA demonstrate a nonuniform picture with predominantly low correlations. This might be due to the fact that these variables are primarily significant for self-regulated learning and less important in the typical school setting, where learning activities and goals are (at least for younger pupils) strongly prestructured and controlled by the teacher (Corno and Snow 1986). Apart from that there certainly cannot be expected any simple, direct, linear correlations between volitional characteristics and SA, but complex interactions and manifold possibilities of mutual compensation, e.g., of inefficient learning strategies by increased effort.

4. Further Perspectives

In Fig. 1 only single determinants and ‘main’ effects of cognitive and motivational determinants on SA were considered. Actually, complex interactions and context specificity as well as the dynamic interplay between variables have to be taken into account. The following points appear important:

(a) Interactions among various individual determinants. For example, maximum performance necessarily requires high degrees of both intelligence and of effort, whereas in the zone of normal average achievement, lack of intelligence can be compensated (as long as it does not drop below a critical threshold value) by increased effort (and vice versa).

(b) Aptitude x treatment interactions and classroom context. Whether test anxiety exerts a strong negative or a low negative impact on SA depends on aspects of the classroom context and on the characteristics of instruction. For example, high test-anxious pupils appear to profit from a high degree of structuring and suffer from a too open, unstructured learning atmosphere, whereas the reverse is true for self-confident pupils with a solid base of prior knowledge (Corno and Snow 1986). Research has shown a large variation between classrooms, concerning the relation between anxiety and achievement as well as between intelligence and achievement (Helmke and Weinert 1999). A similar process of functional compensation has been demonstrated for self-concept (Weinert and Helmke 1987).

(c) Culture specificity. Whereas the patterns and mechanisms of basic cognitive processes that are crucial for learning and achievement are probably universal, many relations shown in Fig. 1 depend on cultural background. For example, the ‘Chinese learner’ does not only show (in the average) a higher level of effort, but the functional role of cognitive processes such as rehearsal is different from the equivalent processes of Western students (Watkins and Biggs 1996).

(d) Dynamic interplay. There is a dynamic interplay between SA and its individual motivational determinants: SA is affected by motivation, e.g., self- concept, and affects motivation itself. From this perspective, SA and its determinants change their states as independent and dependent variables. The degree to which the mutual impact (reciprocity) of academic self-concept and SA is balanced has been the issue of controversy (skill development vs. self- enhancement approach).

Bibliography:

- Beaton A E, Mullis I V S, Martin M O, Gonzales D L, Smith T A 1996 Mathematics Achievement in the Middle School Years. TIMSS International Study Center, Boston

- Corno L, Snow R E 1986 Adapting teaching to individual differences among learners. In: Wittrock M C (ed.) Handbook of Research on Teaching, 3rd edn. Macmillan, New York, pp. 255–96

- Dochy F J R C 1992 Assessment of Prior Knowledge as a Determinant for Future Learning: The Use of Prior Knowledge State Tests and Knowledge Profiles. Kingsley, London

- Gustafsson J-E, Undheim J O 1996 Individual differences in cognitive functions. In: Berliner D C, Calfee R C (eds.) Handbook of Educational Psychology. Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, pp. 186–242

- Helmke A, Weinert F E 1997 Bedingungsfaktoren schulischer Leistungen. In: Weinert F E (ed.) Enzyklopadie der Psychologie. Padagogische Psychologie. Psychologie des Unterrichts und der Schule. Hogrefe, Gottingen, Germany, pp. 71–176

- Helmke A, Weinert F E 1999 Schooling and the development of achievement diff In: Weinert F E, Schneider W (eds.) Individual Development from 3 to 12. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 176–92

- Kuhl J 1992 A theory of self-regulation: Action versus state orientation, self-discrimination, and some applications. Applied Psychology: An International Review 41: 97–129

- Schommer M 1994 An emerging conceptualization of epistemological beliefs and their role in learning. In: Garner R, Alexander P A (eds.) Beliefs about Text and Instruction with Text. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 25–40

- Snow R E, Corno L, Jackson D 1996 Individual differences in affective and conative functions. In: Berliner D C, Calfee R C (eds.) Handbook of Educational Psychology. Simon & Schuster Macmillan, New York, pp. 243–310

- Snow R E, Swanson J 1992 Instructional psychology: Aptitude, adaptation, and assessment. Annual Review of Psychology 43: 583–626

- Sternberg R J, Kaufman J C 1998 Human abilities. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 479–502

- Watkins D A, Biggs J B 1996 The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological, and Contextual Influences. CERC and ACER, Hong Kong

- Weinert F E, Helmke A 1987 Compensatory effects of student self-concept and instructional quality on academic achievement. In: Halisch F, Kuhl J (eds.) Motivation, Intention, and Volition. Springer, Berlin, pp. 233–47

- Weinert F E, Helmke A 1998 The neglected role of individual differences in theoretical models of cognitive development. Learning and Instruction 8(4): 309–23