View sample Rumors And Urban Legends Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Rumors may be defined as unverified or false brief reports (rumors, strictly speaking) or short stories (urban legends) with surprising content. They are passed on among a social milieu as true and current and expressing something of that group’s fears and hopes.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Mythology And Ethics Of Rumor

Ancient civilizations bequeathed us a mythological and ethical concept of rumor. In The Aeneid (IV, 173–197), Virgil (first century BC) personifies the rumor through the features of the goddess Fama, a monster with innumerable eyes, wings, ears, and mouths, and a swift messenger of truth and falsehood. This fabulous description gave inspiration to Shakespeare for Henry IV (1598), in giving Rumor a character of its own, its costume covered with painted tongues. Judeo-Christian tradition reproves gossip as a sin, ranking it with slander. The Talmud puts lachon hara (‘ill tongue’) on equal terms with atheism, adultery, and murder. In Matthew’s Gospel (12: 33–7), it is said that people will also be judged by what comes out of their mouths, and curses those who make a baseless accusation against someone.

The philosophers of the Enlightenment apply the rationalist analysis to ‘fables’ (myths, legends, rumors). For Fontenelle (De l’origine des fables 1684), they are the result of peoples’ ignorance, the strength of the imagination, the verbal transmission of narratives, and the explanatory function of the myth. For Voltaire, doubt does not only relate to supernatural legends, but also to historical narratives. In Le Siecle de Louis XIV (1751), he shows how a rumor could transform a minor war operation—the French army’s crossing of the Rhine River in 1672—into a grandiose epic.

Rumors and legends are deemed to be the result of people’s ignorance, fancy and credulity: A philosophical reprobation can be added to the moral reprobation of rumors.

2. Variety Of Psychosociological Approaches To Rumors

The first scientific studies of rumors started in the 1940s in the USA, during the growth of communication and public opinion researches in social sciences, and being in the state of war, which drew the ruling classes’ attention to the prominent part that rumors play.

Allport and Postman ([1947] 1965) formulated concepts that remain relevant today. First, they established that a given subject would more likely be the subject of rumors if perceived as important and ambiguous by the members of a social group. For example, the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor in 1941 gave way to rumors on account of the importance of this first military attack, which made the Americans fear other assaults, and the ambiguity about the extent of casualties.

Allport and Postman attribute an affective function to rumors, when easing emotional pressure (fear, hostility) of individuals, and a cognitive function, when answering the need for information and ex-planation.

Lastly, through an experimental study (linear trans-mission of information by word of mouth), Allport and Postman pointed out three basic processes that lead to the gradual distortion of the message. Leveling is the rapid reduction of the volume of details. Rumors are inclined to become a short statement with the form ‘subject + predicate’: The subject is any person, animal, thing, institution, social or ethnic group; the predicate is the state or action attributed to the subject. Sharpening consists of selecting, and often magnifying, details. For example, numerical accentuation increases quantity; temporal accentuation brings rumors up to date; size accentuation exaggerates pronounced features (like a caricaturist who turns a small man into a dwarf ). Lastly, assimilation is the alteration of details to fit them into the prejudices, stereotypes, and interests of the rumor transmitters. A rumor is the result of a psychological and collective process reflecting the lowest common denominator of ideas, values, concerns and feelings of the people making up a social group.

It remains necessary to analyze the rumor’s degree of actuality and to study the mechanisms of distortion of facts or factual information. However, it is most important to understand how and why false news is spread and believed.

Shibutani ([1966], 1977) distinguishes among three different kinds of communication channels, in a descending order of social control and institutionalization: formal channels (media, official statements), auxiliary channels (clubs, circles), and informal channels (the word of mouth). At the normal rate of the communication system, information supply and demand are balanced: the main group of information is conveyed by formal channels, and just a few rumors are spread by informal channels. On the contrary, in a critical rate (war, social or economic crisis, natural disaster, etc.), information demand exceeds supply, formal channels fall into discredit and informal channels abound with rumors.

Today, the distinction between official and informal channels must be moderated to the extent that rumors are also circulating by flyer, fax, e-mail, Internet, and even the mass media.

The inquiry into the ‘Rumor in Orleans’ by Morin (1971) is a model case study. Rather than the experimental method, he prefers the clinical approach, investigating in vivo the spread, then the extinction, of a rumor. Rather than take an interest in critical periods, he studies everyday life rumors, in a French provincial town. In spring 1969, it was said in Orleans that young girls vanished in dress shops owned by Jews to supply a ‘white slavery’ trade (i.e., prostitution). Morin tried to understand why so many people had believed these false allegations. The rumor drew its scenario from the pseudo-information of popular culture about white young girls abducted and forced into prostitution in exotic countries. Two ‘catalyses’ converted this scenario into ‘reality.’ First was a popular magazine’s publishing of an unverified anecdote about the failed abduction of a young girl, found unconscious and drugged in back of a dress shop in Grenoble in France. The other was the opening of a clothes department for teenagers, named ‘Aux Oubliettes’ (i.e., secret dungeon) in a medieval decorated basement of a clothing shop in Orleans. The rumor did not affect the shopkeeper, who belonged to the traditional bourgeoisie, but fixed itself on several shops owned by Jews. For Morin, the reactivation of two old myths—white slavery and the Jew—allowed the population to symbolically express the deep fears caused by social and cultural changes at the end of the 1960s. Feminine emancipation and clothing and sexual liberalization fascinate and worry mothers and daughters: the rumor explicates the idea that miniskirts lead girls to prostitution. Second, urban modernization and growing anonymity put people in fear of losing the control of their city. The rumor expresses, through metaphors, the ‘bad’ city hidden behind the ‘good’ one: the trick dressing room, the vault under the shop, the clothes tradesman who also deals in young women, and the Jew as a figure of the one who hides his difference. One of the fundamental contributions by Morin is to have shown that a rumor is carrying a hidden message, an implicit moral, and that the study of rumors must undertake a hermeneutical work to reveal their symbolic meanings.

Morin has also suggested that, in the fight against a rumor, antirumor (denial) was less effective than counter-rumor. Thus, the rumor of Orleans died out, not so much due to police and press denials, but to an emerging counterrumor claiming that the rumormongers were anti-Semites and fascists.

3. A Unified Pattern: The Rumor Syndrome By Rouquette

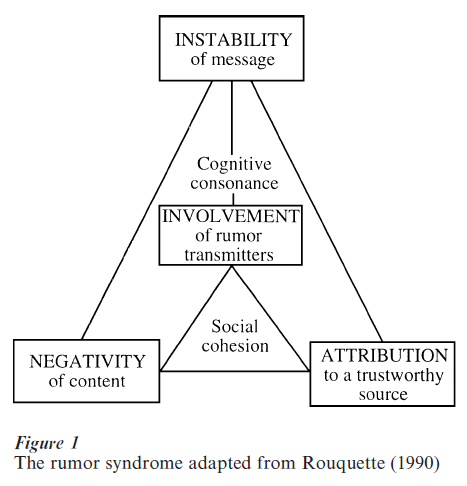

Rouquette (1975, 1990) has built up an unified pattern of rumor in four typical features (see Fig. 1). When information or a narrative presents these characteristics, it is more than likely a rumor or an urban legend.

Instability refers to the alterations of the message, mainly at the time of its formation but also when the rumor is adapted to a new cultural environment. The presence of variants for a rumor or legend is a basic characteristic of the phenomenon.

Involvement is the fact that the rumor transmitter is feeling concerned by the message. The more rumor-mongers are involved in a rumor, the more they will believe it and pass it on. A rumor is any information or story ‘worth telling.’ Involvement is at its maximum when a rumor leads to behavior (e.g., panic).

Negativity is a dominating feature of rumors. Searchers estimate that 90 percent of rumors are ‘noir,’ reporting news of aggression, accident, failure, scar- city, scandal, etc.; and only 10 percent are ‘rose,’ containing optimistic content and attaining imaginary shared hopes and desires.

Lastly, attribution is the alleged source of a rumor. The rumor transmitters mention a trustworthy source, who assures the narrative’s truth.

Rouquette’s pattern offers a strong consistency of its features through six links.

Instability and involvement. Contrary to accepted opinion, the transmission of a message is less accurate when the subjects who spread the rumors are involved —there is an unconscious interference by interest, in their remembrance of the subject—than when they are not concerned by the rumor. In transforming the message, the rumor transmitters tend to keep their cognitive consonance, in other words, the mental consistency of information, opinions, and beliefs they have about a situation.

Instability and negativity. The distortions of the message are commonly negative.

Instability and attribution. The rumor changes and enriches its attributions as it circulates. For example, a relay becomes a source (when rumors are passed on by the press or by a company’s internal memos), a denial becomes a confirmation (in a French variant of the flyer about ‘LSD tattoos,’ the heading ‘The Narcotic Bureau Confirms’ appeared just after the organization denied the allegations. Cf. Campion-Vincent and Renard 1992).

The next three links show the role that rumors play in social cohesion.

Involvement and negativity. The discrediting of ‘others’ is implicitly corollary to giving importance to ‘ourselves.’ This sets up a mental and moral convergence between the rumor transmitter and his or her audience, therefore strengthening the social cohesion.

Involvement and attribution. Calling upon a trust- worthy source weaves social ties that give value to the rumor transmitter.

Negativity and attribution. The more the rumor is negative, the stronger the guarantee of veracity.

Rouquette (1989) has also expressed the idea that rumors are multiple ‘answers’ to a small number of ‘problems’: how to account for an unexplained fact, how to vindicate an attitude or a belief, how to instigate behavior (warning rumors), how to intensify the social differentiation, or how to favor social integration. These problems take shape through themes, whether they are universal or specific of a given culture at a given time. In the Western modern world, the recurring themes of rumors and urban legends relate to just a few preoccupations (Kapferer 1990, Renard 1999): health, sex, money, new techniques, strangers, urban violence, nature, the change of manners, and the supernatural.

4. Folklore’s Contribution To The Study Of Rumors

Since rumors and legends are subjects of research that usually depend on distinct sciences—sociology for the former and folklore for the latter—their profound identity has been hidden for a long time. It was not until the emergence of a new concept—‘modern or urban legend’ (Mullen 1972, Brunvand 1981)—that sociologists and folklorists collaborated profitably and renewed their perspective on their own research topic. Mullen has emphasized the great resemblance between rumor and legend: Both are the result of a collective interactive process, they are usually first spread by word of mouth, their message is passed on as the truth, and their social functions are similar. Rumor and legend are two aspects of the same phenomenon but one aspect sometimes outweighs the other. Studying the legendary aspect of rumors reveals their mythical deep-rootedness. Studying the ‘rumoral’ aspect of legends brings enlightenment to the transformations of content and the production of variants.

This aspect appears in the following tendencies: briefness of content, instability, and actualization, active and brief circulation in a certain time and place and among a given social group. The legendary aspect expresses complementary tendencies: the patterning of the content into a narrative form; the exploitation of motifs and themes, sometimes of ancient origin, emerging from the collective imagination and having strong symbolic contents; insertion into long, sometimes secular, periods of time, spreading internationally (Brunvand 1981, 1993, etc.).

A rumor may expand—become ‘authentic’—and embody itself in a legendary narrative; reciprocally, a legend may be reduced to a mere statement. For instance, ‘There are alligators in the sewers of New York’ is the brief rumor form of the story reporting that New Yorkers brought back baby alligators from Florida, and then disposed of them when they became burdensome by flushing them down the toilet, where they ended up in the sewer (Brunvand 1981).

A similar legend may arise in both a traditional version and a modern version. For instance, the narrative motif ‘Animal lives in person’s body’ is treated in Africa as witchcraft, whereas in the West it is explained by pseudomedical reasons.

In his pertinently headed article ‘From Trolls to Turks,’ Tangherlini (1995) shows many correlations between rumors and urban legends, circulating in modern Denmark, and the traditional narratives of the Danish folklore. He proves that beliefs about immigrants are revived from old motifs concerning supernatural beings (elves, trolls, witches): loathsome food customs, abduction of women or children, physical violence.

It is not accidental that interest in urban legends first arose among the folklorists, at least in English and German-speaking countries. Rumors and contemporary popular narratives are actually modern equivalents of ancient legends, all of them expressing social or symbolic thought.

Bibliography:

- Allport G W, Postman L [1947] 1965 The Psychology of Rumor. Russell and Russell, New York

- Brunvand J H 1981 The Vanishing Hitchhiker: American Urban Legends and Their Meanings. Norton, New York

- Brunvand J H 1993 The Baby Train and Other Lusty Urban Legends. Norton, New York

- Campion-Vincent V, Renard J-B 1992 Legendes urbaines: Rumeurs d’aujourd’hui. Payot, Paris

- Kapferer J-N 1990 Rumors: Uses, Interpretations and Images. Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, NJ

- Morin E 1971 Rumour in Orleans. Blond, London

- Mullen P B 1972 Modern legend and rumor theory. Journal of the Folklore Institute 9: 95–109

- Renard J-B 1999 Rumeurs et legendes urbaines. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

- Rosnow R L, Fine G A 1976 Rumor and Gossip: The Social Psychology of Hearsay. Elsevier, New York

- Rouquette M-L 1975 Les Rumeurs. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris

- Rouquette M-L 1989 La rumeur comme resolution d’un probleme mal defini. Cahiers internationaux de sociologie 86: 117–22

- Rouquette M-L 1990 Le syndrome de rumeur. Communications 52: 119–23

- Shibutani T [1966] 1977 Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor. Bobbs-Merrill, Indianapolis, IN

- Tangherlini T R 1995 From trolls to Turks: Continuity and change in Danish legend tradition. Scandinavian Studies 67(1): 32–62