View sample Reputation Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a religion research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our research paper writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

A reputation exists in the form of an image shared within some public. Applied to a person, it identifies ‘not an intrinsic quality he possesses but rather the opinion other people have of him’ (Bailey 1971). It can also refer to certain collectivities, like a company, occupational category, professional group, organization, or its leadership and, by extension, to just about anything that can somehow be rated or ranked. Thus, we talk about the reputation of a dining establishment, of a vintage year of wine, of an annual event, of a locality or city. All such reputations, whatever they be, are socially constructed. They may or may not be deserved and are always open to challenge. But, as long as they endure, they are real in their consequences.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Over 300 years ago Locke referred to the ‘law of opinion and reputation’ in order to highlight how much reputations were a part of the small politics of everyday life (1690 1894): ‘People have a strong motive to accommodate themselves to the opinions and rules of those with whom they converse … and so they do that which keeps them in reputation with their company, with little regard for the laws of God, or of the magistrate …’ Smith, a century later, argued in similar vein when he located the love of virtue in the desire for ‘being what ought to be approved of,’ a motive he believed to be most strongly felt among persons of middling or inferior status who, possessing none of the privileges associated with noble lineage or inherited wealth, must, in order to distinguish themselves, bring their talents into public view. Besides, they ‘can never be great enough to be above the law … (Their) success … almost always depends upon the favour and good opinion of their neighbours and equals; and without a tolerably regular conduct, these can very seldom be obtained’ (1804).

These ideas persist. Economists represented in a volume edited by Klein (1997) depict society as permeated by a flowing network of reputational relationships, with institutional credentials and certification substituting for reputations based on personal acquaintance.

Insofar as one can extract value from it, a reputation can be further conceptualized as a form of symbolic capital (Bourdieu 1992). It can grow or diminish yet still retain some value so long as people remember. This value is real enough for anyone who feels his or her good name to have been unjustly sullied by the careless or malicious actions of others. Redress can be sought through the courts—not always successfully, to be sure. And tax laws in some countries allow the corporate write-off of expenditures for building and protecting the reputation of a company or its brand name.

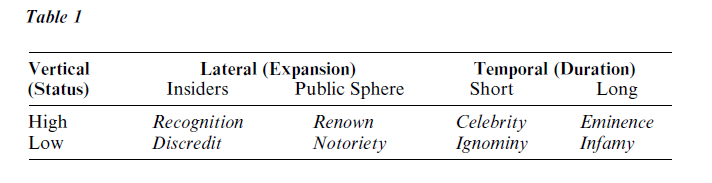

Reputations vary along three dimensions: best known is the vertical dimension that locates an agent or object on a hierarchical scale. A high reputation signifies the attribution of a level of respect, credibility, authority, or competence denied to those who do not measure up to that standard. Reputations, high as well as low, also vary along a lateral dimension, where placement is determined by the size of the public within which a name has currency. To differentiate between these two dimensions, we refer to a reputation for upright character or some talent shared by neighbors, colleagues, professional peers, and other insiders as recognition while reserving the term renown for that more universal recognition that extends beyond a particular reputational community (Lang and Lang 1990). A parallel distinction at the low end of the vertical dimension is between being in disrepute among peers and the notoriety attained when disreputing information carries to the general public. The terms are diagramed in the Table 1 below.

A third temporal dimension has to do with duration in time. Public attention is forever being distracted by new entrants into the limelight. Reputations follow trajectories of different lengths. A celebrity is typically a person who may enjoy moments of fame but thereafter is remembered only by the few with a special interest in preserving the memory. Only the ‘truly great’ achieve the kind of eminence that accounts for their survival in the collective memory as major historical figures (Collins 1998). Alternatively, the ignominy experienced for some heinous deed may be quickly forgotten or be forever remembered in infamy. Most reputations fall somewhere between these extremes. The categories are depicted in the accompanying figure.

Sociologists, and especially historians as well as some literary scholars, have focused mainly on the lateral and temporal dimensions of high status, namely on how particular individuals attain renown and are canonized. Economists and political scientists, many of them employing game theoretical models, as well as some anthropologists have exhibited more interest in how reputations function within particular settings.

1. Effects Of Reputation

Effects can be divided into two general categories: those involving the reactions of others to the reputation of an individual and those that stem from an individual’s anticipation of reactions to their own conduct. Obviously, there is a good deal of overlap between these two.

The effect of a personal reputation on those with whom one directly interacts has been illustrated famously in the fable about the boy who cried ‘Wolf’ once too often. When a wolf actually showed up, as we all have learned, no one in the village heeded his warning, having come to expect just another false alarm. So it is that signals from a source deemed untrustworthy are apt to be ignored and dealings with a party of dubious reliability will, wherever possible, be avoided. But we do not always know enough about the other nor are we at liberty to choose. Where such doubts exist, the willingness to co-operate or enter into an agreement becomes contingent on external enforcement.

How reputations derived from past performances of parties engaged in repetitive play affect both the strategies adopted by competitors and their preferences for partners has been modeled by game theorists. Their highly suggestive work is commendable for its logical rigor. Still, one can question how well their propositions tested in experiments, most of them with only two players interacting within controlled settings, replicate the complexities of real life. For one thing, reputational effects are based not just on personal experience but on word that gets around. Thus, collective attributions are a cardinal factor in the power an American president can wield. Neustadt locates its source, not just in the Constitution but in what others in the Washington political community think and expect of the incumbent. Justified or not, ‘it is the reality on which they act, at least until their calculations turn out wrong … (1990). What the president must demonstrate in the many different games he plays, often all at the same time, is his ability and will to make use of his bargaining advantages. Success breeds success but a pattern of repeated failure is bound to result in a loss of faith in his effectiveness that will reduce his power to persuade.

Similar self-enhancing effects show up in nonpolitical settings. Distinguished scientists get disproportionate credit for their contribution to a collaborative project (Merton 1967). The prestige of a university affects the quality of the faculty it attracts, whose members then, in turn, benefit from their position and raise the prestige of the institution; artists who are already well-known get more exhibitions; the works of writers who have already won prizes are more actively promoted. The epitomizing case is that of a celebrity, described by Boorstin (1961) as someone ‘known for his being known.’

Images may be poor substitutes for more direct knowledge; yet in a world where most people are strangers to one another, there may be nothing else to govern our calculations. Images certainly affect what we buy, how we invest, and how much we are willing to pay (Fombrun 1996). The reassurances provided by an established brand name usually exacts some premium. But nowhere are the returns from a good reputation greater than in the arts, where values are somewhat intangible, subject to fashion, highly dependent on critical and public endorsement (Moulin 1986). The name attached to a work determines not only price but also the attention it gets. The media, very much oriented toward a star system, feed this proclivity, thereby contributing to a pattern in which small differences among a number of top performers, none of them unequivocally superior to the rest, translate into large differences in acclaim (Goode 1978; Frank and Cook 1995).

Even in the corporate world the relation of reputation to measurable performance is not as close as it may seem. High publicity given the Valdez oil spill in Alaska waters was followed by a significant short-term decline in the value of Exxon stock. At least some investors, it has been found, back away from companies not so much because of any loss of faith in their future performance but doubts about their commitment to general community values (Fombrun 1996).

The fear of damage to one’s reputation becomes an incentive for behavior against one’s immediate self-interest. What economists, following Adam Smith, have called the discipline of repeated dealings acts as a deterrent, not always effective, against business selling shoddy goods to naive customers or against lobbyists providing clearly misleading information to legislators. But this response is not simply a matter of honesty but of strategic impression management as, for example, when a college reduces its acceptance rate as part of a marketing strategy to portray itself as highly selective. On the international scene, where to yield ‘on a series of issues when matters at stake are not critical … may (make) it difficult to communicate to the other (side) just when a vital issue has been reached,’ a nation may be moved to act for no other reason than to retain its ‘reputation for action’ (Schelling 1966). Against such an instrumental view, Chong (1992) has argued that, when a reputation becomes part of their identity, people try to live up to it for moral reasons as well, trying to turn themselves into the kind of person they want others to think they are.

Another set of reputational incentives comes into play when the expansion of a reputation into the public sphere creates what Braudy (1986) calls the ‘frenzy of renown’ with numerous effects, some of which are potentially deleterious to one’s moral commitments, whatever these may be. Fame and the appearance of power it gives are sometimes seductive. For example, Gitlin (1980) describes how media attention undermined the connection of some leading activists of the New Left, a movement with a weak organizational structure, to their original reputational community. Competing for a place in the limelight, these ‘leaders’ transformed themselves into ‘unattached celebrities,’ no longer accountable to the rank-and-file but drawn toward increasingly ‘extravagant, ‘‘incidental,’’ expressive actions—actions which made ‘‘good copy’’ because they generated sensational pictures rich in symbolism.’ In sports, the advent of a national public for major-league baseball, largely a product of television, has been associated with a decline in the advantage of playing on one’s home turf. The present-day public, according to Leifer (1995), is less loyal to home-grown athletes and teams but looks for any winner it can celebrate. It is not averse to abandoning a team that falls short of its expectations. By interpreting what were initially random performance differences between contestants, the public casts competitive equals into stable winner and loser roles. The teams react to reputations established early in the season, not only by the public at the game but also by sportscasters and writers when in fact, Leifer contends, many outcomes might easily have gone the other way.

2. From Recognition To Renown

Propositions about the acquisition of fame derive largely from life histories, mostly of successful individuals who by virtue of their background, talent, or associations seemed destined for success. To gain recognition within some domain for some special talent or accomplishment depends on a number of general conditions. Endowment and ability are, without a doubt, prerequisites. But the pool of talent is large and some acclaimed figures have had to overcome what would appear to have been formidable handicaps. Albert Einstein is known to have failed his school examination and Glenn Cunningham, the champion miler for several years, had legs so severely burned as a child that his doctors were not at all sure whether he would even walk again. Regardless of any such handicap, everyone in pursuit of recognition has to do what is necessary to develop the skills that count.

There is, to be sure, a world of difference between measurable improvements of athletic performance or scores in games played according to strict rules and the evolving consensus by which the less tangible abilities prized in domains other than sports come to be validated. Nothing counts unless people take notice. The achievement of a recluse working all alone is more likely to be overlooked than comparable ones by more gregarious contemporaries. Insofar as reputations carry through networks, acceptance by peers and mentors is often the first step toward gaining recognition. Thereafter it becomes a question of how far these networks extend. Persons highly esteemed in one domain may not even be recognized outside its boundaries or can be subject to all sorts of invidious distinctions. Hence, reputations do not easily transfer, even between genotypically similar activities, especially if they are as differentially valued. In most arts, where only some genres are ordained by an arts establishment, an excess of popularity can actually be the kiss of death. Kapsis (1992) traces the career of Alfred Hitchcock, the Hollywood director of many famous films, who transformed himself deliberately from a merely successful maker of movies into a genuine auteur by adopting a new and more acceptable idiom.

The general rule that one is better off not straying too far from the mainstream holds even in the sciences where the highest honors usually go to the innovators. To be working on a problem whose importance has been widely acknowledged increases the likelihood of gaining attention for work that adds only incrementally to existing knowledge. Attaching oneself to important people is a second strategy, equally appropriate to the sciences and to the arts. Yet dissidents denied their place by a complacent establishment can also collectively advance their reputations by banding together, forming their own societies, and using them as a springboard to raise their status. This is how the group of artists denigrated as ‘impressionists,’ due to their apparent disdain for serious subject matter, drew attention to themselves.

Whether recognition within a group converts into renown is highly contingent on distribution and publicity (Becker 1982). Visual artists depend on exhibition space for display of their accomplishments; writers on publishers and booksellers; playwrights on performers and on a suitable stage, and the performers themselves on recordings and bookings in a major medium to display their accomplishments. To be singled out for special praise by influential critics and other mediators of fame is still more important (Moulin 1986). Especially if their judgments stimulate museum purchases, give a theatrical work a permanent place in the repertory, or generate substantial interest in the writings of an author, they can make a household word out of an obscure name. Most likely to bring instant fame are the feats that receive the greatest publicity, like the breaking of an established record in one of the major sports or ventures into entirely new territories in science or in space. A few individuals are singled out as stars with very little acknowledgment of the collective effort that made their achievement possible. Only a small number of scientists know the names of the many highly competent engineers who have make space flight possible.

3. Measuring Reputations

In a society set on rating and ranking everything, there are essentially two approaches to the measurement of reputation: through responses to survey questions and through aggregations of indicators about the actual reactions of some public.

Judgments expressed by survey respondents are most meaningful in settings where just about everyone knows everyone else. Accordingly, performance can be predicted from measures of certain qualities based on average ratings by groups of their peers. No less ascertainable is what the residents of a village community think of their neighbors or which professionals are held in the highest regard by their colleagues. However, the content of any such consensus becomes more problematical the farther removed those queried are from whomever they are asked about. For years pollsters have obtained what legitimately can be called a reputational ranking by asking a representative sample of Americans to name the man and also the woman they most admire. Because respondents were free to name anyone alive, their choices have always been widely scattered with the president and the first lady almost always heading the lists. Their rankings, as well as that of others, has have as much to do with their prominent coverage in the news media as with the respect they enjoy within their particular reputational community.

The American president is of course one of a very small number of celebrities or infamous villains about whom just about everyone has some opinion. Thus, standardized questions about presidential performance approximate a vote and can be the basis for comparing a president’s reputation to that of other actors prominent on the political scene. But there is as yet no general agreement on a standard for measuring other reputations in the public sphere. Should the reputations of corporations be based on the collective judgment of high-level executives, of customers, or of their employees? That of schools on responses from their alumni or of academics from those working in the same discipline? Who does the ranking is particularly important in the arts, governed as they are by the distinction between real ‘quality’ ascertained by art experts and what is merely popular.

When it comes to the past, there is no alternative to querying specialists. This method works best when evaluating a narrowly defined category, like American presidents or justices of the Supreme Court. In the first such survey, 55 experts on the presidency were asked to place each occupant of the office into one of five categories ranging from ‘great’ to ‘failure’ (Schlesinger 1997). Others have queried larger samples with more ‘refined’ methods only to find that the same three— Washington, Lincoln, and Franklin D. Roosevelt— consistently placed at the top, though not always in the same order. Choices of the best and worst presidents have also remained relatively stable with more fluctuation among those ranked in between. Most striking has been the steady rise in reputation of Eisenhower as new information about his presidency has come to light.

Citation counts are one of the most widely used indicators of the reputation of individuals and of academic departments. Such information is very accessible. Because scholars are obliged to cite prior publications on which their own work is built or with which they take issue, the number of references to the work of a scientist or scholar in any particular discipline is assumed to indicate the level of recognition by colleagues. Yet strategic considerations also enter. Citing a particular predecessor can help a neophyte establish a link to one or more of the prestigious figures in their field, thereby drawing the attention of colleagues and enhancing the significance of one’s own work (Camic 1987). The more a field is subject to intellectual fashion the more likely it is that credit for an idea that is very much in the air goes to the more famous.

The frequency with which a particular name appears in the more popular media indicates its role in a broader discourse but there are, at least in some fields and for some individuals, serious discrepancies between name counts for introductory texts and those for more esoteric publications aimed at narrower constituencies. In drawing conclusions from any such enumerations, one needs always to take into account the perspective of publications examined. But any set of similar publications can be useful in examining trends. Rosengren (1987) noted that in texts of Swedish literature the same names that turned up in an earlier period were still prominently reviewed four decades later.

A simple way of gauging the level of eminence (or infamy) attained by any individual is through the cumulation of literature in major libraries, most of whose holdings are now on line. After all, writers are the primary purveyors of fame (Cooley 1927). The number of items a search turns up is a measure of how much what the subjects did and the issues they raised have retained their salience as historical markers. The larger the universe searched the more finely do the findings discriminate. A search limited to full-length biographies would omit many minor figures somewhat renowned in their lifetime. Searches covering long time spans are open to another kind of bias. Although material evidence gets lost over time and some of the eminent of long ago may have left few traces, posterity has had many more opportunities to develop a consensus about those whose ‘lives’ have somehow survived. In terms of number of mentions and pages devoted to each in an authoritative encyclopedia of communication, a few ‘greats’ from the past outranked even the most distinguished contemporary scholars in this burgeoning field (Beniger 1990). It therefore makes sense to restrict such counts to differentiating between the luminaries of a particular time period, whose ideas remain of great interest, and their contemporaneous lesser lights as Collins (1998) does in his study of philosophers.

Another measure focuses less on citations than on decisions made over the years by the custodians of tradition as to what part of the past to preserve. The results are manifest in the number of memorials, shrines, plaques, exhibits, and commemorative events designed to keep alive the memory of a particular person or persons. To obtain a full record of these tributes is difficult, except perhaps for some of the arts where one can ascertain the number of times a composer’s work is performed by major orchestras (Simonton 1986; Mueller 1958) or a play is performed or revived (Griswold 1987). In the visual arts, the aggregate number of works in major museums and on permanent display is an appropriate indicator of collective curatorial judgment but somewhat confounded by rarity. Because there is not enough work by some of the greatest artists to meet the demand of museums, a single indicator, based on their holdings, has to be supplemented by information about the frequency with which work is circulated in special loan exhibitions, many of which are organized precisely to commemorate the artist.

The market is the ultimate but albeit imperfect arbiter of value. Many variables, like age, rarity, and condition, enter into prices paid for works and memorabilia associated with past eminence. Still, for items comparable on these variables, consistent price differentials represent the consensus of their relative worth. They are, to this extent, valid measures of reputation.

4. The Survival Of Reputation

Over time, as memories fade, the lives of most people end up in the dust bins of history. There is a continuing sorting out of those deemed memorable. As to likely survival in the collective memory, posthumous reputations are the combined effect of two conditions: the rhetorical force of the accomplishments of the deceased on society or some domain in their lifetime and the extent to which, even if for altogether different reasons, an accomplishment still touches the imagination of posterity. ‘Greatness’ can also be conferred retrospectively as validation of or correction to earlier valuations.

The renown achieved in a person’s lifetime enhances the chance for reputational survival. It facilitates contact with persons who become the mediators of one’s reputation across generations (Zilsel 1972). Kings, popes, presidents, generals, and executives may have archivists at their command but those without an official position have to find their place in the right networks. Attention from colleagues attracts students, who will pass their valuations of a scholar on to the next generation. For an artist, critical acclaim brings wealthy collectors, whose purchases have a good chance of ending up in a museum. It is by no means uncommon for the admirers of some creative person to form a society dedicated to preserving and promoting their reputation.

Famous people also leave more traces. Anything connected with them gains value, which provides incentives for preserving mementoes of their lives, especially any pictures, diaries, and correspondence that evidence their thoughts and character. Insofar as their paths have crossed those of other famous people, many of the letters they have written or received are likely to survive in some archive and to attract scholars prepared to ferret out still more material.

Subjects have some, though limited, control over the record on which their reputational fate will come to depend. Those who take care to keep and organize records strengthen their claim on the memory of posterity. It has become standard for a president to initiate the setting up of a library, even though his papers would be saved in any event. Some famous people are known to have taken the further step of purging from their files items inconsistent with the image they want to project. Writers have burned manuscripts they believed detrimental to their reputation. There are painters who destroyed systematically all pictures produced during a period for which they did not want to be remembered. Theodore Roosevelt dictated letters intended for posterity. Thomas Hardy actually controlled the biography his wife published under her own name following his death (Hamilton 1994). President Richard Nixon’s attempt to retain control over his secretly recorded tapes failed. The same impulse shows up in instructions to estate executors to convert the residence of the deceased into a landmark or to use remaining assets to preserve his or her reputation. To be sure, these wishes are not always followed or followed only halfheartedly.

Some factors affecting the survival of reputation remain beyond the control of the individual: first, there are the accidental circumstances of birth and death. Possible candidates for reputational immortality can be born into a time or live in a place where no one acts to preserve the record of their deeds. Thus, the Chinese predecessor of Gutenberg remains unknown and Columbus rather than Leif Ericson is hailed as the discoverer of America. As to the timing or circumstances of death, a long productive life full of honors is an obvious reputational asset but to be struck down in the prime of life by an assassin, a tragic illness, or unfortunate accident has the potential to transform the victim into an icon. No one can possibly know how John F. Kennedy would have been remembered had he served for a full one or two terms. Yet the halo put around him by his untimely death overshadows the modest achievements and all too apparent failures of his administration. A still more striking example is that of Anne Frank. Would her diary, translated into many languages, have had the same impact if she had survived the Holocaust? And had she survived, would she have tolerated the publication by her father of this very private document from which he excised passages that displeased him?

The availability of survivors, like Anne Frank’s father, with a personal stake in cultivating remembrance depends, in part, on such demographic factors as marriage, fertility, and longevity. Lang and Lang (1990), studying the revival of etching as an original art form in the late-nineteenth century, found that it had attracted an unusually large number—at least for that time period—of talented women well recognized during their lifetimes, yet today much less well remembered than their male peers. Two demographic circumstances contributed to this reputational disparity: the extraordinary longevity of the women and the much smaller number ever married or, if married, with children. Hence, they outlived, often by decades, not only their spouses but also their colleagues, close friends, publishers, dealers, admiring collectors, as well as the collapse of the etching craze, so that there was often no one still around to mourn their death and write the obligatory obit. Also, because unmarried women had neither mate nor daughter to take on the tedious task of record keeping, material for an artistic biography or definite catalogue raisonne are often lacking.

All reputational communities have boundaries. The heroes celebrated in one may be largely unknown in another. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the different statesmen, military heroes, literary figures and so forth each nation celebrates. National perspectives even intrude into the allocation of credit for achievement universally recognized as breakthroughs. Obviously, the pioneers of space exploration who have received the greatest attention in America differ from those celebrated in the former Soviet Union. The inventor of the incandescent lamp, as remembered by Americans, is Thomas Edison, who was in fact preceded by Joseph Swan, who first exhibited his successful carbon-filament lamp in England, where he had greater impact. His factory near Newcastle rivaled Edison’s in prosperity. But whereas Edison immediately patented everything, Swan was slow to do so. Nor did he have a wealthy sponsor like Henry Ford, who thought him the greatest man alive and started collecting Edison memorabilia as early as 1905, and ultimately erecting a shrine in Dearborn, Michigan by transporting, piece by piece, and reassembling the inventor’s New Jersey laboratory. But for a reputation to cross all cultural and geographic boundaries, the achievement behind it must appear unique and be an inspiration for people all over the world.

Time creates its own boundaries. There is only so much room at the top, so that at some point what Collins (1998) calls the law of small numbers comes into play. Secondary figures recede into the background as new interests emerge. The survivors are those whose deeds and accomplishments still speak to the present. Posterity has some leeway in its view of the past. Not only does it select but it reinterprets continuously, particularly when it comes to the work of writers and artists. The qualities that contemporaries most admired in Hawthorne’s oeuvre (Tompkins 1984) and in Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa are not the same ones that touch us today (Boas 1940). Put another way, eminence derives from the persistence of beliefs about persons and their deeds and creations that have changed their domain in some fundamental way. The larger the number of domains affected, the greater the likelihood that their reputations will live on.

The development, change, preservation, and decline of reputations as well as how they function have to be understood as part of an ongoing social process. Experiments and statistical studies provide useful information, mostly about outcomes, but require supplementation of case material on the process as it unfolds in a particular context. Qualitative evidence, when derived from more than one case and subjected to systematic analysis, is not to be discounted as merely anecdotal.

Bibliography:

- Bailey F G 1971 Gifts and poison. In: Gifts and Poison: The Politics of Reputation. Blackwell, Oxford, UK, pp. 1–25

- Becker H 1982 Art Worlds. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Beniger J R 1990 Who are the most important theorists of communication. Communication Research 17: 698–715

- Boorstin D J 1961 The Image: Or, What Happened to the American Dream. Atheneum, New York

- Bourdieu P 1992 Les regles de l’art. Editions du Seuil, Paris

- Braudy L 1986 The Frenzy of Renown. Oxford University Press, New York

- Camic C 1987 The making of a method: A historical reinterpretation of early Parsons. American Sociological Review 52: 421–39

- Chong D 1992 Reputation and cooperative behavior. Social Science Information 31: 683–709

- Collins R 1998 The Sociology of Philosophy: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Belknap Press, Cambridge, UK

- Cooley C H 1927 Fame. In: Social Process. Scribner’s, New York, pp. 112–24

- Fombrun C J 1996 Reputation: Realizing the Value from the Corporate Image. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

- Frank R H, Cook P J 1995 The Winner-take-all Society: How More and More Americans Compete for Ever Fewer and Bigger Prizes, Encouraging Economic Waste, Income Inequality, and an Impoverished Cultural Life. Free Press, New York

- Gitlin T 1980 The Whole World is Watching: Mass Media in the Making & Unmaking of the New Left. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Goode W J 1978 The Celebration of Heroes: Prestige as a Social Control System. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA

- Griswold W 1986 Renaissance Revivals: City Comedy and Revenge Tragedy in the London Theatre, 1576–1980. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Hamilton I 1994 Keepers of the Flame: Literary Estates and the Rise of Biography from Shakespeare to Plath. Faber & Faber, Boston

- Kapsis R E 1992 Hitchcock: The Making of a Reputation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Klein D B (ed.) 1997 Reputation: Studies in the Voluntary Elicitation of Good Conduct. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

- Lang G E, Lang K 1990 Etched in Memory: The Building and Survival of Artistic Reputation. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC

- Leifer E M 1995 Making the Majors: The Transformation of Team Sports in America. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

- Locke J 1690/1894 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- Merton R K 1967 The Matthew effect in science. Science 159(5): 56–63

- Mueller J H 1958 The American Symphony Orchestra: A Social History of Musical Taste. Calder, London

- Neustadt R E 1990 Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan. Free Press, New York

- Rosengren K E 1987 Literary criticism: Future invented. Poetics 16: 295–325

- Schelling T C 1966 Arms and Influence. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT

- Schlesinger A M Jr 1997 Rating the presidents: Washington to Clinton. Political Science Quarterly 112: 179–90

- Smith A 1804 The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Cadell & Davis, London

- Tompkins J 1984 Masterpiece theatre: The politics of Hawthorne’s literary reputation. American Quarterly 36: 617–42

- Zilsel E 1926/1972 Die Entstehung des Geniebriffes: Ein Beitrag zur Ideengeschichte der Antike und des Fruhkapitalismus. Olms, Hildesheim, Germany