View sample psychological assessment in school settings research paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of psychology research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Psychological assessment in school settings is in many ways similar to psychological assessment in other settings. This may be the case in part because the practice of modern psychological assessment began with an application to schools (Fagan, 1996). However, the practice of psychological assessment in school settings may be discriminated from practices in other settings by three characteristics: populations, problems, and procedures (American Psychological Association, 1998).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Psychological assessment in school settings primarily targets children, and secondarily serves the parents, families, and educators of those children. In the United States, schools offer services to preschool children with disabilities as young as 3 years of age and are obligated to provide services to individuals up to 21 years of age. Furthermore, schools are obligated to educate all children, regardless of their physical, behavioral, or cognitive disabilities or gifts. Because public schools are free and attendance is compulsory for children, schools are more likely than private or fee-for-service settings to serve individuals who are poor or members of a minority group or have language and cultural differences. Consequently, psychological assessment must respond to the diverse developmental, cultural, linguistic, ability, and individual differences reflected in school populations.

Psychological assessment in school settings primarily targets problems of learning and school adjustment. Although psychologists must also assess and respond to other developmental, social, emotional, and behavioral issues, the primary focus behind most psychological assessment in schools is understanding and ameliorating learning problems. Children and families presenting psychological problems unrelated to learning are generally referred to services in nonschool settings. Also, school-based psychological assessment addresses problem prevention, such as reducing academic or social failure. Whereas psychological assessment in other settings is frequently not invoked until a problem is presented, psychological assessment in schools may be used to prevent problems from occurring.

Psychological assessment in school settings draws on procedures relevant to the populations and problems served in schools. Therefore, school-based psychologists emphasize assessment of academic achievement and student learning, use interventions that emphasize educational or learning approaches, and use consultation to implement interventions. Because children experience problems in classrooms, playgrounds, homes, and other settings that support education, interventions to address problems are generally implemented in the setting where the problem occurs. School-based psychologists generally do not provide direct services (e.g., play therapy) outside of educational settings. Consequently, psychologists in school settings consult with teachers, parents, and other educators to implement interventions. Psychological assessment procedures that address student learning, psychoeducational interventions, and intervention implementation mediated via consultation are emphasized to a greater degree in schools than in other settings.

The remainder of this research paper will address aspects of psychological assessment that distinguish practices in schoolbased settings from practices in other settings. The paper is organized into four major sections: the purposes, current practices, assessment of achievement and future trends of psychological assessment in schools.

Purposes of Psychological Assessment in Schools

There are generally six distinct, but related, purposes that drive psychological assessment. These are screening, diagnosis, intervention, evaluation, selection, and certification. Psychological assessment practitioners may address all of these purposes in their school-based work.

Screening

Psychological assessment may be useful for detecting psychological or educational problems in school-aged populations. Typically, psychologists employ screening instruments to detect students at risk for various psychological disorders, including depression, suicidal tendencies, academic failure, social skills deficits, poor academic competence, and other forms of maladaptive behaviors. Thus, screening is most often associated with selected or targeted prevention programs (see Coie et al., 1993, and Reiss & Price, 1996, for a discussion of contemporary prevention paradigms and taxonomies).

The justification for screening programs relies on three premises: (a) individuals at significantly higher than average risk for a problem can be identified prior to onset of the problem; (b) interventions can eliminate later problem onset or reduce the severity, frequency, and duration of later problems; and (c) the costs of the screening and intervention programs are justified by reduced fiscal or human costs. In some cases, psychologists justify screening by maintaining that interventions are more effective if initiated prior to or shortly after problem onset than if they are delivered later.

Three lines of research validate the assumptions supporting screening programs in schools. First, school-aged children who exhibit later problems may often be identified with reasonable accuracy via screening programs, although the value of screening varies across problem types (Durlak, 1997). Second, there is a substantial literature base to support the efficacy of prevention programs for children (Durlak, 1997; Weissberg & Greenberg, 1998). Third, prevention programs are consistently cost effective and usually pay dividends of greater than 3:1 in cost-benefit analyses (Durlak, 1997).

Although support for screening and prevention programs is compelling, there are also concerns about the value of screening using psychological assessment techniques. For example, the consequences of screening mistakes (i.e., false positives and false negatives) are not always well understood. Furthermore, assessment instruments typically identify children as being at risk, rather than identifying the social, educational, and other environmental conditions that put them at risk. The focus on the child as the problem (i.e., the so-called “disease model”) may undermine necessary social and educational reforms (see Albee, 1998). Screening may also be more appropriate for some conditions (e.g., suicidal tendencies, depression, social skills deficits) than for others (e.g., smoking), in part because students may not be motivated to change (Norman, Velicer, Fava, & Prochaska, 2000). Placement in special programs or remedial tracks may reduce, rather than increase, students’ opportunity to learn and develop. Therefore, the use of psychological assessment in screening and prevention programs should consider carefully the consequential validity of the assessment process and should ensure that inclusion in or exclusion from a prevention program is based on more than a single screening test score (see standard 13.7, American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 1999, pp. 146–147).

Diagnosis

Psychological assessment procedures play a major, and often decisive, role in diagnosing psychoeducational problems. Generally, diagnosis serves two purposes: establishing eligibility for services and selecting interventions. The use of assessment to select interventions will be discussed in the next section. Eligibility for special educational services in the United States is contingent upon receiving a diagnosis of a psychological or psychoeducational disability. Students may qualify for special programs (e.g., special education) or privileges (e.g., testing accommodations) under two different types of legislation. The first type is statutory (e.g., the Americans with Disabilities Act), which requires schools to provide a student diagnosed with a disability with accommodations to the general education program (e.g., extra time, testing accommodations), but not educational programs. The second type of legislation is entitlement (e.g., Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), in which schools must provide special services to students with disabilities when needed. These special services may include accommodations to the general education program and special education services (e.g., transportation, speech therapy, tutoring, placement in a special education classroom). In either case, diagnosis of a disability or disorder is necessary to qualify for accommodations or services.

Statutory legislation and educational entitlement legislation are similar, but not identical, in the types of diagnoses recognized for eligibility purposes. In general, statutory legislation is silent on how professionals should define a disability. Therefore, most diagnoses to qualify children under statutory legislation invoke medical (e.g., American Psychiatric Association, 2000) nosologies. Psychological assessment leading to a recognized medical or psychiatric diagnosis is a necessary, and in some cases sufficient, condition for establishing a student’s eligibility for services. In contrast, entitlement legislation is specific in defining who is (and is not) eligible for services. Whereas statutory and entitlement legislation share many diagnostic categories (e.g., learning disability, mental retardation), they differ with regard to specificity and recognition of other diagnoses. For example, entitlement legislation identifies “severely emotionally disturbed” as a single category consisting of a few broad diagnostic indicators, whereas most medical nosologies differentiate more types and varieties of emotional disorders.An example in which diagnostic systems differ is attention deficit disorder (ADD): The disorder is recognized in popular psychological and psychiatric nosologies (e.g., American Psychiatric Association, 2000), but not in entitlement legislation.

Differences in diagnostic and eligibility systems may lead to somewhat different psychological assessment methods and procedures, depending on the purpose of the diagnosis. School-based psychologists tend to use diagnostic categories defined by entitlement legislation to guide their assessments, whereas psychologists based in clinics and other nonschool settings tend to use medical nosologies to guide psychological assessment. These differences are generally compatible, but they occasionally lead to different decisions about who is, and is not, eligible for accommodations or special education services.Also, psychologists should recognize that eligibility for a particular program or accommodation is not necessarily linked to treatment or intervention for a condition. That is, two students who share the same diagnosis may have vastly different special programs or accommodations, based in part on differences in student needs, educational settings, and availability of resources.

Intervention

Assessment is often invoked to help professionals select an intervention from among an array of potential interventions (i.e., treatment matching). The fundamental assumption is that the knowledge produced by a psychological assessment improves treatment or intervention selection. Although most psychologists would accept the value for treatment matching at a general level of assessment, the notion that psychological assessment results can guide treatment selection is more controversial with respect to narrower levels of assessment. For example, determining whether a student’s difficulty with written English is caused by severe mental retardation, deafness, lack of exposure to English, inconsistent prior instruction, or a language processing problem would help educators select interventions ranging from operant conditioning approaches to placement in a program using American Sign Language, English as a Second Language (ESL) programs, general writing instruction with some support, or speech therapy.

However, the utility of assessment to guide intervention is less clear at narrower levels of assessment. For example, knowing that a student has a reliable difference between one or more cognitive subtest or composite scores, or fits a particular personality category or learning style profile, may have little value in guiding intervention selection. In fact, some critics (e.g., Gresham & Witt, 1997) have argued that there is no incremental utility for assessing cognitive or personality characteristics beyond recognizing extreme abnormalities (and such recognition generally does not require the use of psychological tests). Indeed, some critics argue that data-gathering techniques such as observation, interviews, records reviews, and curriculum-based assessment of academic deficiencies (coupled with common sense) are sufficient to guide treatment matching (Gresham & Witt, 1997; Reschly & Grimes, 1995). Others argue that knowledge of cognitive processes, and in particular neuropsychological processes, is useful for treatment matching (e.g., Das, Naglieri, & Kirby, 1994; Naglieri, 1999; Naglieri & Das, 1997). This issue will be discussed later in the paper.

Evaluation

Psychologists may use assessment to evaluate the outcome of interventions, programs, or other educational and psychological processes. Evaluation implies an expectation for a certain outcome, and the outcome is usually a change or improvement (e.g., improved reading achievement, increased social skills). Increasingly, the public and others concerned with psychological services and education expect students to show improvement as a result of attending school or participating in a program. Psychological assessment, and in particular, assessment of student learning, helps educators decide whether and how much students improve as a function of a curriculum, intervention, or program. Furthermore, this information is increasingly of interest to public and lay audiences concerned with accountability (see Elmore & Rothman; 1999; McDonnell, McLaughlin, & Morrison, 1997).

Evaluation comprises two related purposes: formative evaluation (e.g., ongoing progress monitoring to make instructional decisions, providing feedback to students), and summative evaluation (e.g., assigning final grades, making pass/fail decisions, awarding credits). Psychological assessment is helpful for both purposes. Formative evaluation may focus on students (e.g., curriculum-based measurement of academic progress; changes in frequency, duration, or intensity of social behaviors over time or settings), but it may also focus on the adults involved in an intervention. Psychological assessment can be helpful for assessing treatment acceptability (i.e., the degree to which those executing an intervention find the procedure acceptable and are motivated to comply with it; Fairbanks & Stinnett, 1997), treatment integrity (i.e., adherence to a specific intervention or treatment protocol; Wickstrom, Jones, LaFleur, & Witt, 1998), and goal attainment (the degree to which the goals of the intervention are met; MacKay, Somerville, & Lundie, 1996). Because psychologists in educational settings frequently depend on others to conduct interventions, they must evaluate the degree to which interventions are acceptable and determine whether interventions were executed with integrity before drawing conclusions about intervention effectiveness. Likewise, psychologists should use assessment to obtain judgments of treatment success from adults in addition to obtaining direct measures of student change to make formative and summative decisions about student progress or outcomes.

Selection

Psychological assessment for selection is an historic practice that has become controversial. Students of intellectual assessment may remember that Binet and Simon developed the first practical test of intelligence to help Parisian educators select students for academic or vocational programs. The use of psychological assessment to select—or assign—students to educational programs or tracks was a major function of U.S. school-based psychologists in the early to mid-1900s (Fagan, 2000). However, the general practice of assigning students to different academic tracks (called tracking) fell out of favor with educators, due in part to the perceived injustice of limiting students’ opportunity to learn. Furthermore, the use of intellectual ability tests to assign students to tracks was deemed illegal by U.S. federal district court, although later judicial decisions have upheld the assignment of students to different academic tracks if those assignments are based on direct measures of student performance (Reschly, Kicklighter, & McKee, 1988). Therefore, the use of psychological assessment to select or assign students to defferent educational tracks is allowed if the assessment is nonbiased and is directly tied to the educational process. However, many educators view tracking as ineffective and immoral (Oakes, 1992), although recent research suggests tracking may have beneficial effects for all students, including those in the lowest academic tracks (Figlio & Page, 2000). The selection activities likely to be supported by psychological assessment in schools include determining eligibility for special education (discussed previously in the section titled “Diagnosis”), programs for gifted children, and academic honors and awards (e.g., National Merit Scholarships).

Certification

Psychological assessment rarely addresses certification, because psychologists are rarely charged with certification decisions. An exception to this rule is certification of student learning, or achievement testing. Schools must certify student learning for graduation purposes, and incresingly for other purposes, such as promotion to higher grades or retention for an additional year in the same grade.

Historically, teachers make certification decisions with little use of psychological assessment. Teachers generally certify student learning based on their assessment of student progress in the course via grades. However, grading practices vary substantially among teachers and are often unreliable within teachers, because teachers struggle to reconcile judgments of student performance with motivation and perceived ability when assigning grades (McMillan & Workman, 1999). Also, critics of public education have expressed grave concerns regarding teachers’ expectations and their ability and willingness to hold students to high expectations (Ravitch, 1999).

In response to critics’ concerns and U.S. legislation (e.g., Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act), schools have dramatically increased the use and importance of standardized achievement tests to certify student knowledge. Because states often attach significant student consequences to their standardized assessments of student learning, these tests are called high-stakes tests (see Heubert & Hauser, 1999). About half of the states in the United States currently use tests in whole or in part for making promotion and graduation decisions (National Governors Association, 1998); consequently, psychologists should help schools design and use effective assessment programs. Because these high-stakes tests are rarely given by psychologists, and because they do not assess more psychological attributes such as intelligence or emotion, one could exclude a discussion of high-stakes achievement tests from this research paper. However, I include them here and in the section on achievement testing, because these assessments are playing an increasingly prominent role in schools and in the lives of students, teachers, and parents. I also differentiate highstakes achievement tests from diagnostic assessment. Although diagnosis typically includes assessment of academic achievement and also has profound effects on students’ lives (i.e., it carries high stakes), two features distinguish high-stakes achievement tests from other forms of assessment: (a) all students in a given grade must take high-stakes achievement tests, whereas only students who are referred (and whose parents consent) undergo diagnostic assessment; and (b) highstakes tests are used to make general educational decisions (e.g., promotion, retention, graduation), whereas diagnostic assessment is used to determine eligibility for special education.

Current Status and Practices of Psychological Assessment in Schools

The primary use of psychological assessment in U.S. schools is for the diagnosis and classification of educational disabilities. Surveys of school psychologists (e.g.,Wilson & Reschly, 1996) show that most school psychologists are trained in assessment of intelligence, achievement, and social-emotional disorders, and their use of these assessments comprises the largest single activity they perform. Consequently, most school-based psychological assessment is initiated at the request of an adult, usually a teacher, for the purpose of deciding whether the student is eligible for special services.

However, psychological assessment practices range widely according to the competencies and purposes of the psychologist. Most of the assessment technologies that school psychologists use fall within the following categories:

- Interviews and records reviews.

- Observational systems.

- Checklists and self-report techniques.

- Projective techniques.

- Standardized tests.

- Response-to-intervention approaches.

Methods to measure academic achievement are addressed in a separate section of this research paper.

Interviews and Records Reviews

Most assessments begin with interviews and records reviews. Assessors use interviews to define the problem or concerns of primary interest and to learn about their history (when the problems first surfaced, when and under what conditions problems are likely to occur); whether there is agreement across individuals, settings, and time with respect to problem occurrence; and what individuals have done in response to the problem. Interviews serve two purposes: they are useful for generating hypotheses and for testing hypotheses. Unstructured or semistructured procedures are most useful for hypothesis generation and problem identification, whereas structured protocols are most useful for refining and testing hypotheses.

Unstructured and semistructured interview procedures typically follow a sequence in which the interviewer invites the interviewee to identify his or her concerns, such as the nature of the problem, when the person first noticed it, its frequency, duration, and severity, and what the interviewee has done in response to the problem. Most often, interviews begin with open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me about the problem”) and proceed to more specific questions (e.g., “Do you see the problem in other situations?”). Such questions are helpful in establishing the nature of the problem and in evaluating the degree to which the problem is stable across individuals, settings, and time. This information will help the assessor evaluate who has the problem (e.g., “Do others share the same perception of the problem?”) and to begin formulating what might influence the problem (e.g., problems may surface in unstructured situations but not in structured ones). Also, evidence of appropriate or nonproblem behavior in one setting or at one time suggests the problem may be best addressed via motivational approaches (i.e., supporting the student’s performance of the appropriate behavior). In contrast, the failure to find any prior examples of appropriate behavior suggests the student has not adequately learned the appropriate behavior and thus needs instructional support to learn the appropriate behavior.

Structured interview protocols used in school settings are usually driven by instructional theory or by behavioral theory. For example, interview protocols for problems in reading or mathematics elicit information about the instructional practices the teacher uses in the classroom (see Shapiro, 1989). This information can be useful in identifying more and less effective practices and to develop hypotheses that the assessor can evaluate through further assessment.

Behavioral theories also guide structured interviews. The practice of functional assessment of behavior (see Gresham, Watson, & Skinner, 2001) first identifies one or more target behaviors. These target behaviors are typically defined in specific, objective terms and are defined by the frequency, duration, and intensity of the behavior. The interview protocol then elicits information about environmental factors that occur before, during, and after the target behavior. This approach is known as the ABCs of behavior assessment, in that assessors seek to define the antecedents (A), consequences (C), and concurrent factors (B) that control the frequency, duration, or intensity of the target behavior. Assessors then use their knowledge of the environment-behavior links to develop interventions to reduce problem behaviors and increase appropriate behaviors. Examples of functional assessment procedures include systems developed by Dagget, Edwards, Moore, Tingstrom, and Wilczynski (2001), Stoiber and Kratochwill (2002), and Munk and Karsh (1999). However, functional assessment of behavior is different from functional analysis of behavior.Whereas a functional assessment generally relies on interview and observational data to identify links between the environment and the behavior, a functional analysis requires that the assessor actually manipulate suspected links (e.g., antecedents or consequences) to test the environment-behavior link. Functional analysis procedures are described in greater detail in the section on response-to-intervention assessment approaches.

Assessors also review permanent products in a student’s record to understand the medical, educational, and social history of the student.Among the information most often sought in a review of records is the student’s school attendance history, prior academic achievement, the perspectives of previous teachers, and whether and how problems were defined in the past. Although most records reviews are informal, formal procedures exist for reviewing educational records (e.g., Walker, Block-Pedego, Todis, & Severson, 1991). Some of the key questions addressed in a records review include whether the student has had adequate opportunity to learn (e.g., arecurrent academic problems due to lack of or poor instruction?) and whether problems are unique to the current setting or year. Also, salient social (e.g., custody problems, foster care) and medical conditions (e.g., otitis media, attention deficit disorder) may be identified in student records. However, assessors should avoid focusing on less salient aspects of records (e.g., birth weight, developmental milestones) when defining problems, because such a focus may undermine effective problem solving in the school context (Gresham, Mink, Ward, MacMillan, & Swanson, 1994).Analysis of students’permanent products (rather than records about the student generated by others) is discussed in the section on curriculum-based assessment methodologies.

Together, interviews and records reviews help define the problem and provide an historical context for the problem. Assessors use interviews and records reviews early in the assessment process, because these procedures focus and inform the assessment process. However, assessors may return to interview and records reviews throughout the assessment process to refine and test their definition and hypotheses about the student’s problem. Also, psychologists may meld assessment and intervention activities into interviews, such as in behavioral consultation procedures (Bergan & Kratochwill, 1990), in which consultants use interviews to define problems, analyze problem causes, select interventions, and evaluate intervention outcomes.

Observational Systems

Most assessors will use one or more observational approaches as the next step in a psychological assessment. Although assessors may use observations for purposes other than individual assessment (e.g., classroom behavioral screening, evaluating a teacher’s adherence to an intervention protocol), the most common use of an observation is as part of a diagnostic assessment (see Shapiro & Kratochwill, 2000). Assessors use observations to refine their definition of the problem, generate and test hypotheses about why the problem exists, develop interventions within the classroom, and evaluate the effects of an intervention.

Observation is recommended early in any diagnostic assessment process, and many states in the United States require classroom observation as part of a diagnostic assessment. Most assessors conduct informal observations early in a diagnostic assessment because they want to evaluate the student’s behavior in the context in which the behavior occurs. This allows the assessor to corroborate different views of the problem, compare the student’s behavior to that of his or her peers (i.e., determine what is typical for that classroom), and detect features of the environment that might contribute to the referral problem.

Observation systems can be informal or formal. The informal approaches are, by definition, idiosyncratic and vary among assessors. Most informal approaches rely on narrative recording, in which the assessor records the flow of events and then uses the recording to help refine the problem definition and develop hypotheses about why the problem occurs.These narrative qualitative records provide rich data for understanding a problem, but they are rarely sufficient for problem definition, analysis, and solution.

As is true for interview procedures, formal observation systems are typically driven by behavioral or instructional theories. Behavioral observation systems use applied behavioral analysis techniques for recording target behaviors. These techniques include sampling by events or intervals and attempt to capture the frequency, duration, and intensity of the target behaviors. One system that incorporates multiple observation strategies is the Ecological Behavioral Assessment System for Schools (Greenwood, Carta, & Dawson, 2000); another is !Observe (Martin, 1999). Both use laptop or handheld computer technologies to record, summarize, and report observations and allow observers to record multiple facets of multiple behaviors simultaneously.

Instructional observation systems draw on theories of instruction to target teacher and student behaviors exhibited in the classroom. The Instructional Environment Scale-II (TIES-II; Ysseldyke & Christenson, 1993) includes interviews, direct observations, and analysis of permanent products to identify ways in which current instruction meets and does not meet student needs. Assessors use TIES-II to evaluate 17 areas of instruction organized into four major domains. The Instructional Environment Scale-II helps assessors identify aspects of instruction that are strong (i.e., matched to student needs) and aspects of instruction that could be changed to enhance student learning. The ecological framework presumes that optimizing the instructional match will enhance learning and reduce problem behaviors in classrooms. This assumption is shared by curriculum-based assessment approaches described later in the paper. Although TIES-II has a solid foundation in instructional theory, there is no direct evidence of its treatment utility reported in the manual, and one investigation of the use of TIES-II for instructional matching (with the companion Strategies and Tactics for Educational Interventions, Algozzine & Ysseldyke, 1992) showed no clear benefit (Wollack, 2000).

The Behavioral Observation of Student in School (BOSS; Shapiro, 1989) is a hybrid of behavioral and instructional observation systems. Assessors use interval sampling procedures to identify the proportionof time a target studentis on or off task. These categories are further subdivided into active or passive categories (e.g., actively on task, passively off task) to describe broad categories of behavior relevant to instruction. The BOSS also captures the proportion of intervals teachers actively teach academic content in an effort to link teacher and student behaviors.

Formal observational systems help assessors by virtue of their precision, the ability to monitor change over time and circumstances, and their structured focus on factors relevant to the problem at hand. Formal observation systems often report fair to good interrater reliability, but they often fail to report stability over time. Stability is an important issue in classroom observations, because observer ratings are generally unstable if based on three or fewer observations (see Plewis, 1988). This suggests that teacher behaviors are not consistent. Behavioral observation systems overcome this limitation via frequent use (e.g., observations are conducted over multiple sessions); observations based on a single session (e.g., TIES-II) are susceptible to instability but attempt to overcome this limitation via interviews of the teacher and student. Together, informal and formal observation systems are complementary processes in identifying problems, developing hypotheses, suggesting interventions, and monitoring student responses to classroom changes.

Checklists and Self-Report Techniques

School-based psychological assessment also solicits information directly from informants in the assessment process. In addition to interviews, assessors use checklists to solicit teacher and parent perspectives on student problems. Assessors may also solicit self-reports of behavior from students to help identify, understand, and monitor the problem.

Schools use many of the checklists popular in other settings with children and young adults. Checklists to measure a broad range of psychological problems include the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991a, 1991b), Devereux Rating Scales (Naglieri, LeBuffe, & Pfeiffer, 1993a, 1993b), and the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC; C. R. Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). However, school-based assessments also use checklists oriented more specifically to schools, such as the Connors Rating Scale (for hyperactivity; Connors, 1997), the Teacher-Child Rating Scale (T-CRS; Hightower et al., 1987), and the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990).

The majority of checklists focus on quantifying the degree to which the child’s behavior is typical or atypical with respect to age or grade level peers. These judgments can be particularly useful for diagnostic purposes, in which the assessor seeks to establish clinically unusual behaviors. In addition to identifying atypical social-emotional behaviors such as internalizing or externalizing problems, assessors use checklists such as the Scales of Independent Behavior (Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996) to rate adaptive and maladaptive behavior. Also, some instruments (e.g., the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales; Sparrow, Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984) combine semistructured parent or caregiver interviews with teacher checklists to rate adaptive behavior. Checklists are most useful for quantifying the degree to which a student’s behavior is atypical, which in turn is useful for differential diagnosis of handicapping conditions. For example, diagnosis of severe emotional disturbance implies elevated maladaptive or clinically atypical behavior levels, whereas diagnosis of mental retardation requires depressed adaptive behavior scores.

The Academic Competence Evaluation Scale (ACES; DiPerna & Elliott, 2000) is an exception to the rule that checklists quantify abnormality. Teachers use the ACES to rate students’ academic competence, which is more directly relevant to academic achievement and classroom performance than measures of social-emotional or clinically unusual behaviors. The ACES includes a self-report form to corroborate teacher and student ratings of academic competencies.Assessors can use the results of the teacher and student forms of the ACES with the Academic Intervention Monitoring System (AIMS; S. N. Elliott, DiPerna, & Shapiro, 2001) to develop interventions to improve students’ academic competence. Most other clinically oriented checklists lend themselves to diagnosis but not to intervention.

Self-report techniques invite students to provide open- or closed-ended response to items or probes. Many checklists (e.g., the CBCL, BASC, ACES, T-CRS, SSRS) include a self-report form that invites students to evaluate the frequency or intensity of their own behaviors. These self-report forms can be useful for corroborating the reports of adults and for assessing the degree to which students share perceptions of teachers and parents regarding their own behaviors. Triangulating perceptions across raters and settings is important because the same behaviors are not rated identically across raters and settings. In fact, the agreement among raters, and across settings, can vary substantially (Achenbach, McConaughy, & Howell, 1987). That is, most checklist judgments within a rater for a specific setting are quite consistent, suggesting high reliability. However, agreement between raters within the same setting, or agreement within the same rater across setting, is much lower, suggesting that many behaviors are situation specific, and there are strong rater effects for scaling (i.e., some raters are more likely to view behaviors as atypical than other raters).

Other self-report forms exist as independent instruments to help assessors identify clinically unusual feelings or behaviors. Self-report instruments that seek to measure a broad range of psychological issues include the Feelings, Attitudes, and Behaviors Scale for Children (Beitchman, 1996), the Adolescent Psychopathology Scale (W. M. Reynolds, 1988), and the Adolescent Behavior Checklist (Adams, Kelley, & McCarthy, 1997). Most personality inventories address adolescent populations, because younger children may not be able to accurately or consistently complete personality inventories due to linguistic or developmental demands. Other checklists solicit information about more specific problems, such as social support (Malecki & Elliott, 1999), anxiety (March, 1997), depression (Reynolds, 1987), and internalizing disorders (Merrell & Walters, 1998).

One attribute frequently associated with schooling is selfesteem. The characteristic of self-esteem is valued in schools, because it is related to the ability to persist, attempt difficult or challenging work, and successfully adjust to the social and academic demands of schooling. Among the most popular instruments to measure self-esteem are the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (Piers, 1984), the Self-Esteem Inventory (Coopersmith, 1981), the Self-Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1985), and the Multi-Dimensional SelfConcept Scale (Bracken, 1992).

One form of a checklist or rating system that is unique to schools is the peer nomination instrument. Peer nomination methods invite students to respond to items such as “Who in your classroom is most likely to fight with others?” or “Who would you most like to work with?” to identify maladaptive and prosocial behaviors. Peer nomination instruments (e.g., the Oregon Youth Study Peer Nomination Questionnaire, Capaldi & Patterson, 1989) are generally reliable and stable over time (Coie, Dodge, & Coppotelli, 1982). Peer nomination instruments allow school-based psychological assessment to capitalize on the availability of peers as indicators of adjustment, rather than relying exclusively on adult judgement or selfreport ratings.

The use of self-report and checklist instruments in schools is generally similar to their use in nonschool settings. That is, psychologists use self-report and checklist instruments to quantify and corroborate clinical abnormality. However, some instruments lend themselves to large-scale screening programs for prevention and early intervention purposes (e.g., the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale) and thus allow psychologists in school settings the opportunity to intervene prior to onset of serious symptoms. Unfortunately, this is a capability that is not often realized in practice.

Projective Techniques

Psychologists in schools use instruments that elicit latent emotional attributes in response to unstructured stimuli or commands to evaluate social-emotional adjustment and abnormality. The use of projective instruments is most relevant for diagnosis of emotional disturbance, in which the psychologist seeks to evaluate whether the student’s atypical behavior extends to atypical thoughts or emotional responses.

Most school-based assessors favor projective techniques requiring lower levels of inference. For example, the Rorschach tests are used less often than drawing tests. Draw-a-persontests or human figure drawings are especially popular in schools because they solicit responses that are common (children are often asked to draw), require little language mediation or other culturally specific knowledge, and can be group administered for screening purposes, and the same drawing can be used to estimate mental abilities and emotional adjustment. Although human figure drawings have been popular for many years, their utility is questionable, due in part to questionable psychometric characteristics (Motta, Little, & Tobin, 1993). However, more recent scoring system have reasonable reliability and demonstrated validity for evaluating mental abilities (e.g., Naglieri, 1988) and emotional disturbance (Naglieri, McNeish,&Bardos,1991).Theuseofprojectivedrawingtests is controversial, with some arguing that psychologists are prone to unwarranted interpretations (Smith & Dumont, 1995) and others arguing that the instruments inherently lack sufficient reliability and validity for clinical use (Motta et al., 1993). However, others offer data supporting the validity of drawings when scored with structured rating systems (e.g., Naglieri & Pfeiffer, 1992), suggesting the problem may lie more in unstructured or unsound interpretation practices than in drawing tests per se.

Another drawing test used in school settings is the Kinetic Family Drawing (Burns & Kaufman, 1972), in which children are invited to draw their family “doing something.” Assessors then draw inferences about family relationships based on the position and activities of the family members in the drawing. Other projective assessments used in schools include the Rotter Incomplete Sentences Test (Rotter, Lah, & Rafferty, 1992), which induces a projective assessment of emotion via incomplete sentences (e.g., “I am most afraid of ”). General projective tests, such as the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT; Murray & Bellak, 1973), can be scored for attributes such as achievement motivation (e.g., Novi & Meinster, 2000). There are also apperception tests that use educational settings (e.g., the Education Apperception Test; Thompson & Sones, 1973) or were specifically developed for children (e.g., the Children’s Apperception Test; Bellak & Bellak, 1992). Despite these modifications, apperception tests are not widely used in school settings. Furthermore, psychological assessment in schools has tended to reduce projective techniques, favoring instead more objective approaches to measuring behavior, emotion, and psychopathology.

Standardized Tests

Psychologists use standardized tests primarily to assess cognitive abilities and academic achievement. Academic achievement will be considered in its own section later in this research paper. Also, standardized assessments of personality and psychopathology using self-report and observational ratings are described in a previous section. Consequently, this section will describe standardized tests of cognitive ability.

Standardized tests of cognitive ability may be administered to groups of students or to individual students by an examiner. Group-administered tests of cognitive abilities were popular for much of the previous century as a means for matching students to academic curricula. As previously mentioned, Binet and Simon (1914) developed the first practical test of intelligence to help Parisian schools match students to academic or vocational programs, or tracks. However, the practice of assigning students to academic programs or tracks based on intelligence tests is no longer legally defensible (Reschly et al., 1988). Consequently, the use of groupadministered intelligence tests has declined in schools. However, some schools continue the practice to help screen for giftedness and cognitive delays that might affect schooling. Instruments that are useful in group-administered contexts include the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test (Otis & Lennon, 1996), the Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (Naglieri, 1993), the Raven’s Matrices Tests (Raven, 1992a, 1992b), and the Draw-A-Person (Naglieri, 1988). Note that, with the exception of the Otis-Lennon School Ability Test, most of these screening tests use culture-reduced items. The reduced emphasis on culturally specific items makes them more appropriate for younger and ethnically and linguistically diverse students. Although culture-reduced, group-administered intelligence tests have been criticized for their inability to predict school performance, there are studies that demonstrate strong relationships between these tests and academic performance (e.g., Naglieri & Ronning, 2000).

The vast majority of cognitive ability assessments in schools use individually administered intelligence test batteries. The most popular batteries include the Weschler IntelligenceScaleforChildren—ThirdEdition(WISC-III;Wechsler, 1991), the Stanford Binet Intelligence Test—Fourth Edition (SBIV; Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986), the WoodcockJohnson Cognitive Battery—Third Edition (WJ-III COG; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2000b), and the Cognitive Assessment System (CAS; Naglieri & Das, 1997). Psychologists may also use Wechsler Scales for preschool (Wechsler, 1989) and adolescent (Wechsler, 1997) assessments and may use other, less popular, assessment batteries such as the Differential Ability Scales (DAS; C.D. Elliott, 1990) or the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children (KABC; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1983) on occasion.

Two approaches to assessing cognitive abilities other than broad intellectual assessment batteries are popular in schools: nonverbal tests and computer-administered tests. Nonverbal tests of intelligence seek to reduce prior learning and, in particular, linguistic and cultural differences by using language- and culture-reduced test items (see Braden, 2000). Many nonverbal tests of intelligence also allow for nonverbal responses and may be administered via gestures or other nonverbal or languagereduced means. Nonverbal tests include the Universal Nonverbal Intelligence Test (UNIT; Bracken & McCallum, 1998), the Comprehensive Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (CTONI; Hammill, Pearson, & Wiederholt, 1997), and the Leiter International Performance Scale—Revised (LIPS-R; Roid & Miller, 1997). The technical properties of these tests is usually good to excellent, although they typically provide less data to support their validity and interpretation than do more comprehensive intelligence test batteries (Athanasiou, 2000).

Computer-administered tests promise a cost- and timeefficient alternative to individually administered tests. Three examples are the General Ability Measure for Adults (Naglieri & Bardos, 1997), the Multidimensional Aptitude Battery (Jackson, 1984), and the Computer Optimized Multimedia Intelligence Test (TechMicro, 2000). In addition to reducing examiner time, computer-administered testing can improve assessment accuracy by using adaptive testing algorithms that adjust the items administered to most efficiently target the examinee’s ability level. However, computer-administered tests are typically normed only on young adult and adult populations, and many examiners are not yet comfortable with computer technologies for deriving clinical information. Therefore, these tests are not yet widely used in school settings, but they are likely to become more popular in the future.

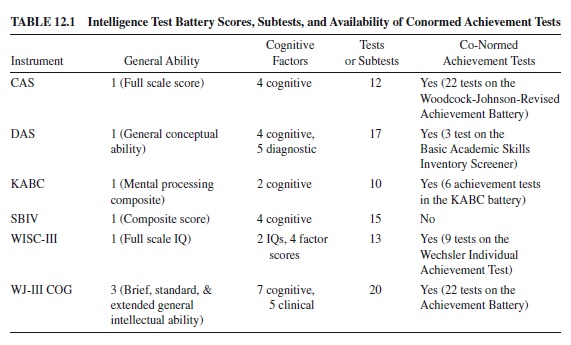

Intelligence test batteries use a variety of item types, organized into tests or subtests, to estimate general intellectual ability. Batteries produce a single composite based on a large number of tests to estimate general intellectual ability and typically combine individual subtest scores to produce composite or factor scores to estimate more specific intellectual abilities. Most batteries recommend a successive approach to interpreting the myriad of scores the battery produces (see Sattler, 2001). The successive approach reports the broadest estimate of general intellectual ability first and then proceeds to report narrower estimates (e.g., factor or composite scores based on groups of subtests), followed by even narrower estimates (e.g., individual subtest scores). Assessors often interpret narrower scores as indicators of specific, rather than general, mental abilities. For each of the intellectual assessment batteries listed, Table 12.1 describes the estimates of general intellectual ability, the number of more specific score composites, the number of individual subtests, and whether the battery has a conormed achievement test.

The practice of drawing inferences about a student’s cognitive abilities from constellations of test scores is usually known as profile analysis (Sattler, 2001), although it is more precisely termed ipsative analysis (see Kamphaus, Petoskey, & Morgan, 1997). The basic premise of profile analysis is that individual subtest scores vary, and the patterns of variation suggest relative strengths and weaknesses within the student’s overall level of general cognitive ability. Test batteries support ipsative analysis of test scores by providing tables that allow examiners to determine whether differences among scores are reliable (i.e., unlikely given that the scores are actually equal in value) or unusual (i.e., rarely occurring in the normative sample). Many examiners infer unusual deficits or strengths in a student’s cognitive abilities based on reliable or unusual differences among cognitive test scores, despite evidence that this practice is not well supported by statistical or logical analyses (Glutting, McDermott, Watkins, Kush, & Konold, 1997; but see Naglieri, 2000).

Examiners use intelligence test scores primarily for diagnosing disabilities in students. Examiners use scores for diagnosis in two ways: to find evidence that corroborates the presence of a particular disability (confirmation), or to find evidence to disprove the presence of a particular disability (disconfirmation). This process is termed differential diagnosis, in that different disability conditions are discriminated from each other on the basis of available evidence (including test scores). Furthermore, test scores are primary in defining cognitive disabilities, whereas test scores may play a secondary role in discriminating other, noncognitive disabilities from cognitive disabilities.

Three examples illustrate the process. First, mental retardation is a cognitive disability that is defined in part by intellectual ability scores falling about two standard deviations below the mean.An examiner who obtains a general intellectual ability score that falls more than two standard deviations below the mean is likely to consider a diagnosis of mental retardation in a student (given other corroborating data), whereas a score above the level would typically disconfirm a diagnosis of mental retardation. Second, learning disabilities are cognitive disabilities defined in part by an unusually low achievement score relative to the achievement level that is predicted or expected given the student’s intellectual ability. An examiner who finds an unusual difference between a student’s actual achievement score and the achievement score predicted on the basis of the student’s intellectual ability score would be likely to consider a diagnosis of a learning disability, whereas the absence of such a discrepancy would typically disconfirm the diagnosis. Finally, an examiner who is assessing a student with severe maladaptive behaviors might use a general intellectual ability score to evaluate whether the student’s behaviors might be due to or influenced by limited cognitive abilities; a relatively low score might suggest a concurrent intellectual disability, whereas a score in the low average range would rule out intellectual ability as a concurrent problem.

The process and logic of differential diagnosis is central to most individual psychological assessment in schools, because most schools require that a student meet the criteria for one or more recognized diagnostic categories to qualify for special education services. Intelligence test batteries are central to differential diagnosis in schools (Flanagan, Andrews, & Genshaft, 1997) and are often used even in situations in which the diagnosis rests entirely on noncognitive criteria (e.g., examiners assess the intellectual abilities of students with severe hearing impairments to rule out concomitant mental retardation). It is particularly relevant to the practice of identifying learning disabilities, because intellectual assessment batteries may yield two forms of evidence critical to confirming a learning disability: establishing a discrepancy between expected and obtained achievement, and identifying a deficit in one or more basic psychological processes. Assessors generally establish aptitude-achievement discrepancies by comparing general intellectual ability scores to achievement scores, whereas they establish a deficit in one or more basic psychological processes via ipsative comparisons of subtest or specific ability composite scores.

However, ipsative analyses may not provide a particularly valid approach to differential diagnosis of learning disabilities (Ward, Ward, Hatt, Young, & Mollner, 1995), nor is it clear that psychoeducational assessment practices and technologies are accurate for making differential diagnoses (MacMillan, Gresham, Bocian, & Siperstein, 1997). Decisionmaking teams reach decisions about special education eligibility that are only loosely related to differential diagnostic taxonomies (Gresham, MacMillan, & Bocian, 1998), particularly for diagnosis mental retardation, behavior disorders, and learning disabilities (Bocian, Beebe, MacMillan, & Gresham, 1999; Gresham, MacMillan, & Bocian, 1996; MacMillan, Gresham, & Bocian, 1998). Although many critics of traditional psychoeducational assessment believe intellectual assessment batteries cannot differentially diagnose learning disabilities primarily because defining learning disabilities in terms of score discrepancies is an inherently flawed practice, others argue that better intellectual ability batteries are more effective in differential diagnosis of learning disabilities (Naglieri, 2000, 2001).

Differential diagnosis of noncognitive disabilities, such as emotional disturbance, behavior disorders, and ADD, is also problematic (Kershaw & Sonuga-Barke, 1998). That is, diagnostic conditions may not be as distinct as educational and clinical classification systems imply. Also, intellectual ability scores may not be useful for distinguishing among some diagnoses. Therefore, the practice of differential diagnosis, particularly with respect to the use of intellectual ability batteries for differential diagnosis of learning disabilities, is a controversial—yet ubiquitous—practice.

Response-to-Intervention Approaches

An alternative to differential diagnosis in schools emphasizes students’responses to interventions as a means of diagnosing educational disabilities (see Gresham, 2001). The logic of the approach is based on the assumption that the best way to differentiate students with disabilities from students who have not yet learned or mastered academic skills is to intervene with the students and evaluate their response to the intervention. Students without disabilities are likely to respond well to the intervention (i.e., show rapid progress), whereas students without disabilities are unlikely to respond well (i.e., show slower or no progress). Studies of students with diagnosed disabilities suggest that they indeed differ from nondisabled peers in their initial levels of achievement (low) and their rate of response (slow; Speece & Case, 2001).

The primary benefit of a response-to-intervention approach is shifting the assessment focus from diagnosing and determining eligibility for special services to a focus on improving the student’s academic skills (Berninger, 1997). This benefit is articulated within the problem-solving approach to psychological assessment and intervention in schools (Batsche & Knoff, 1995). In the problem-solving approach, a problem is the gap between current levels of performance and desired levels of performance (Shinn, 1995). The definitions of current and desired performance emphasize precise, dynamic measures of student performance such as rates of behavior. The assessment is aligned with efforts to intervene and evaluates the student’s response to those efforts. Additionally, a response-to-intervention approach can identify ways in which the general education setting can be modified to accommodate the needs of a student, as it focuses efforts on closing the gap between current and desired behavior using pragmatic, available means.

The problems with the response-to-intervention are logical and practical. Logically, it is not possible to diagnose based on response to a treatment unless it can be shown that only people with a particular diagnosis fail to respond. In fact, individuals with and without disabilities respond to many educational interventions (Swanson & Hoskyn, 1998), and so the premise that only students with disabilities will fail to respond is unsound. Practically, response-to-intervention judgments require accurate and continuous measures of student performance, the ability to select and implement sound interventions, and the ability to ensure that interventions are implemented with reasonable fidelity or integrity. Of these requirements, the assessor controls only the accurate and continuous assessment of performance. Selection and implementation of interventions is often beyond the assessor’s control, as nearly all educational interventions are mediated and delivered by the student’s teacher. Protocols for assessing treatment integrity exist (Gresham, 1989), although treatment integrity protocols are rarely implemented when educational interventions are evaluated (Gresham, MacMillan, Beebe, & Bocian, 2000).

Because so many aspects of the response-to-treatment approach lie beyond the control of the assessor, it has yet to garner a substantial evidential base and practical adherents. However, a legislative shift in emphasis from a diagnosis/ eligibility model of special education services to a responseto-intervention model would encourage the development and practice of response-to-intervention assessment approaches (see Office of Special Education Programs, 2001).

Summary

The current practices in psychological assessment are, in many cases, similar to practices used in nonschool settings. Assessors use instruments for measuring intelligence, psychopathology, and personality that are shared by colleagues in other settings and do so for similar purposes. Much of contemporary assessment is driven by the need to differentially diagnose disabilities so that students can qualify for special education. However, psychological assessment in schools is more likely to use screening instruments, observations, peernomination methodologies, and response-to-intervention approaches than psychological assessment in other settings. If the mechanisms that allocate special services shift from differential diagnosis to intervention-based decisions, it is likely that psychological assessment in schools would shift away from traditional clinical approaches toward ecological, intervention-based models for assessment (Prasse & Schrag, 1998).

Assessment of Academic Achievement

Until recently, the assessment of academic achievement would not merit a separate section in a research paper on psychological assessment in schools.In the past, teachers and educational administrators were primarily responsible for assessing student learning, except for differentially diagnosing a disability. However, recent changes in methods for assessing achievement, and changes in the decisions made from achievement measures, have pushed assessment of academic achievement to center stage in many schools. This section will describe the traditional methods for assessing achievement (i.e., individually administered tests used primarily for diagnosis) and then describe new methods for assessing achievement. The section concludes with a review of the standards and testing movement that has increased the importance of academic achievement assessment in schools. Specifically, the topics in this section include the following:

- Individually administered achievement tests.

- Curriculum-based assessment and measurement.

- Performance assessment and portfolios.

- Large-scale tests and standards-based educational reform.

Individually Administered Tests

Much like individually administered intellectual assessment batteries, individually administered achievement batteries provide a collection of tests to broadly sample various academic achievement domains. Among the most popular achievement batteries are the Woodcock-Johnson Achievement Battery— Third Edition (WJ-III ACH; Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2000a) the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test—Second Edition (WIAT-II; The Psychological Corporation, 2001), the Peabody Individual Achievement Test—Revised (PIAT-R; Markwardt, 1989), and the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement (KTEA; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1985).

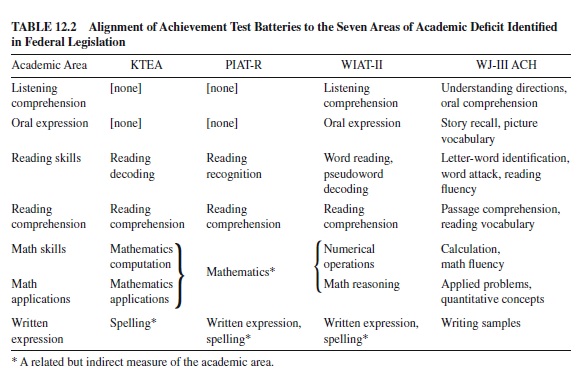

The primary purpose of individually administered academic achievement batteries is to quantify student achievement in ways that support diagnosis of educational disabilities. Therefore, these batteries produce standard scores (and other normreference scores, such as percentiles and stanines) that allow examiners to describe how well the student scores relative to a norm group. Often, examiners use scores from achievement batteries to verify that the student is experiencing academic delays or to compare achievement scores to intellectual ability scores for the purpose of diagnosing learning disabilities. Because U.S. federal law identifies seven areas in which students may experience academic difficulties due to a learning disability, most achievement test batteries include tests to assess those seven areas. Table 12.2 lists the tests within each academic achievement battery that assess the seven academic areas identified for learning disability diagnosis.

Interpretation of scores from achievement batteries is less hierarchical or successive than for intellectual assessment batteries.That is, individual test scores are often used to represent an achievement domain. Some achievement test batteries combine two or more test scores to produce a composite. For example, the WJ-III ACH combines scores from the Passage Comprehension and Reading Vocabulary tests to produce a Reading Comprehension cluster score. However, most achievement batteries use a single test to assess a given academic domain, and scores are not typically combined across academic domains to produce more general estimates of achievement.

Occasionally, examiners will use specific instruments to assess academic domains in greater detail. Examples of more specialized instruments include the Woodcock Reading Mastery Test—Revised (Woodcock, 1987), the Key Math Diagnostic Inventory—Revised (Connolly, 1988), and the Oral and Written Language Scales (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1995). Examiners are likely to use these tests to supplement an achievement test battery (e.g., neither the KTEA nor PIAT-R includes tests of oral language) or to get additional information that could be useful in refining an understanding of the problem or developing an academic intervention. Specialized tests can help examiners go beyond a general statement (e.g., math skills are low) to more precise problem statements (e.g., the student has not yet mastered regrouping procedures for multidigit arithmetic problems). Some achievement test batteries (e.g., the WIAT-II) also supply error analysis protocols to help examiners isolate and evaluate particular skills within a domain.

One domain not listed among the seven academic areas in federal law that is of increasing interest to educators and assessors is the domain of phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness comprises the areas of grapheme-phoneme relationships (e.g., letter-sound links), phoneme manipulation, and other skills needed to analyze and synthesize print to language. Reading research increasingly identifies low phonemic awareness as a major factor in reading failure and recommends early assessment and intervention to enhance phonemic awareness skills (National Reading Panel, 2000). Consequently, assessors serving younger elementary students may seek and use instruments to assess phonemic awareness. Although some standardized test batteries (e.g., WIAT-II, WJ-IIIACH) provide formal measures of phonemic awareness, most measures of phonemic awareness are not standardized and are experimental in nature (Yopp, 1988). Some standardized measures of phonemic awareness not contained in achievement test batteries include the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1999) and The Phonological AwarenessTest (Robertson & Salter, 1997).

Curriculum-Based Assessment and Measurement

Although standardized achievement tests are useful for quantifying the degree to which a student deviates from normative achievement expectations, such tests have been criticized. Among the most persistent criticisms are these:

- The tests are not aligned with important learning outcomes.

- The tests are unable to provide formative evaluation.

- The tests describe student performance in ways that are not understandable or linked to instructional practices.

- The tests are inflexible with respect to the varying instructional models that teachers use.

- The tests cannot be administered, scored, and interpreted in classrooms.

- The tests fail to communicate to teachers and students what is important to learn (Fuchs, 1994).

Curriculum-based assessment (CBA; see Idol, Nevin, & Paolucci-Whitcomb, 1996) and measurement (CBM; see Shinn, 1989, 1995) approaches seek to respond to these criticisms. Most CBA and CBM approaches use materials selected from the student’s classroom to measure student achievement, and they therefore overcome issues of alignment (i.e., unlike standardized batteries, the content of CBA or CBM is directly drawn from the specific curricula used in the school), links to instructional practice, and sensitivity and flexibility to reflect what teachers are doing. Also, most CBM approaches recommend brief (1–3 minute) assessments 2 or more times per week in the student’s classroom, a recommendation that allows CBM to overcome issues of contextual value (i.e., measures are taken and used in the classroom setting) and allows for formative evaluation (i.e., decisions about what is and is not working). Therefore, CBA and CBM approaches to assessment provide technologies that are embedded in the learning context by using classroom materials and observing behavior in classrooms.

The primary distinction between CBA and CBM is the intent of the assessment. Generally, CBA intends to provide information for instructional planning (e.g., deciding what curricular level best meets a student’s needs). In contrast, CBM intends to monitor the student’s progress in response to instruction. Progress monitoring is used to gauge the outcome of instructional interventions (i.e., deciding whether the student’s academic skills are improving). Thus, CBA methods provide teaching or planning information, whereas CBM methods provide testing or outcome information. The metrics and procedures for CBA and CBM are similar, but they differ as a function of the intent of the assessment.

The primary goal of most CBA is to identify what a student has and has not mastered and to match instruction to the student’s current level of skills. The first goal is accomplished by having a repertoire of curriculum-based probes that broadly reflect the various skills students should master. The second goal (instructional matching) varies the difficulty of the probes, so that the assessor can identify the ideal balance between instruction that is too difficult and instruction that is too easy for the student. Curriculum-based assessment identifies three levels of instructional match:

- Frustration level. Task demands are too difficult; the student will not sustain task engagement and will generally not learn because there is insufficient understanding to acquire and retain skills.

- Instructional level. Task demands balance task difficulty, so that new information and skills are presented and required, with familiar content or mastered skills, so that students sustain engagement in the task. Instructional level provides the best trade-off between new learning and familiar material.

- Independent/Mastery level. Task demands are sufficiently easy or familiar to allow the student to complete the tasks with no significant difficulty. Although mastery level materials support student engagement, they do not provide many new or unfamiliar task demands and therefore result in little learning.

Instructional match varies as a function of the difficulty of the task and the support given to the student. That is, students can tolerate more difficult tasks when they have direct support from a teacher or other instructor, but students require lower levels of task difficulty in the absence of direct instructional support.

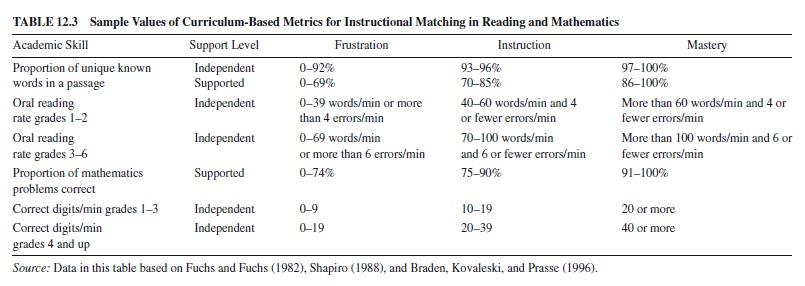

Curriculum-based assessment uses direct assessment using behavioral principles to identify when instructional demands are at frustration, instruction, or mastery levels. The behavioral principles that guide CBA and CBM include defining behaviors in their smallest meaningful unit of behavior (e.g., a word read aloud in context); objectivity and precision of assessment (e.g., counting the frequency of a specific behavior); and repeated measurement over time. Therefore, CBA and CBM approaches tend to value metrics that are discrete, that can be counted and measured as rates of behavior, and that are drawn from students’ responses in their classroom context using classroom materials. For example, reading skills might be counted as the proportion of words the student can identify in a given passage or the number of words the student reads aloud in 1 minute. Mathematics skills could be measured as the proportion of problems solved correctly in a set, or the number or correct digits produced per minute in a 2-minute timed test.

Curriculum-based assessment protocols define instructional match between the student and the material in terms of these objective measures of performance. For example, a passage in which a student recognizes less than 93% of the words is deemed to be at frustration level. Likewise, a third-grade student reading aloud at a rate of 82 words/min with 3 errors/min is deemed to be reading a passage that is at instructional level; a passage that the student could read aloud at a rate of more than 100 words/min. with 5 errors would be deemed to be at the student’s mastery level. Table 12.3 provides examples of how assessors can use CBA and CBM metrics to determine the instructional match for task demands in reading and mathematics.

Whereas assessors vary the type and difficulty of task demands in a CBA approach to identify how best to match instruction to a student, CBM approaches require assessors to hold task type and difficulty constant and interpret changes in the metrics as evidence of improving student skill. Thus, assessors might develop a set of 20 reading passages, or 20 probes of mixed mathematics problem types of similar difficulty levels, and then randomly and repeatedly administer these probes to a student over time to evaluate the student’s academic progress. In most instances, the assessor would chart the results of these 1-min or 2-min samples of behavior to create a time series. Increasing rates of desired behavior (e.g., words read aloud per minute) and stable or decreasing rates of errors (e.g., incorrect words per minute) indicate an increase in a student’s skills.

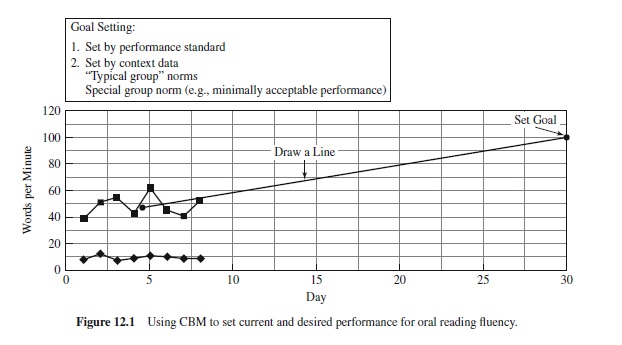

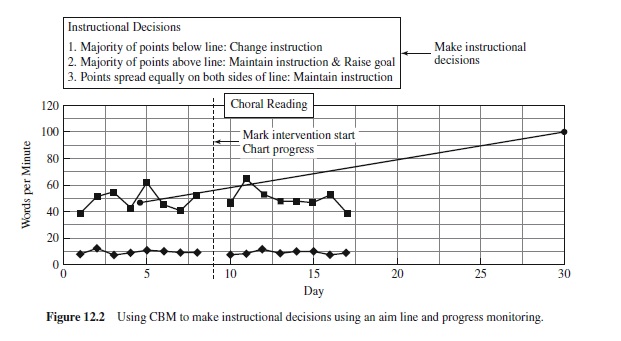

Figures 12.1 and 12.2 present oral reading fluency rates for a student. Figure 12.1 plots the results of eight 1-min reading probes, indicating the number of words the student read correctly, and the number read incorrectly, in one minute. The assessor calculated the median words/min correct for the eight data points and placed an X in the middle of the collected (baseline) data series. The assessor then identified an instructional goal—that is, that the student would read 100 words/min correctly within 30 days. The line connecting the student’s current median performance and the assessor’s goal is an aim line, or the rate of improvement needed to ensure that the student meets the goal. Figure 12.2 shows the intervention selected to achieve the goal (choral reading) and the chart reflecting the student’s progress toward the goal. Given the tendency of the student’s progress to fall below the aim line, the assessor concluded that this instructional intervention was not sufficient to meet the performance goal. Assuming that the assessor determined that the choral reading approach was conducted appropriately, these results would lead the assessor to select a more modest goal or a different intervention.

Curriculum-based assessment and CBM approaches promise accurate instructional matching and continuous monitoring of progress to enhance instructional decisionmaking. Also, school districts can develop CBM norms to provide scores similar to standardized tests (see Shinn, 1989) for screening and diagnostic purposes (although it is expensive to do so). Generally, research supports the value of these approaches. They are reliable and consistent (Hintze, Owen, Shapiro, & Daly, 2000), although there is some evidence of slight ethnic and gender bias (Kranzler, Miller, & Jordan, 1999). The validity of CBA and CBM measures is supported by correspondence to standardized achievement measures and other measures of student learning (e.g., Hintze, Shapiro, Conte, & Basile, 1997; Kranzler, Brownell, & Miller, 1998) and evidence that teachers value CBA methods more than standardized achievement tests (Eckert & Shapiro, 1999). Most important, CBA matching and CBM monitoring of mathematics performance yields more rapid increases in academic achievement among mildly disabled students than among peers who were not provided with CBM monitoring (Allinder, Bolling, Oats, & Gagnon, 2000; Stecker & Fuchs, 2000).

However, CBA and CBM have some limitations. One such limitation is the limited evidence supporting the positive effects of CBA and CBM for reading achievement (Nolet & McLaughlin, 1997; Peverly & Kitzen, 1998). Others criticize CBA and CBM for failing to reflect constructivist, cognitively complex, and meaning-based learning outcomes and for having some of the same shortcomings as standardized tests (Mehrens & Clarizio, 1993). Still, CBA and CBM promise to align assessment with learning and intervention more directly than standardized tests of achievement and to lend themselves to continuous progress monitoring in ways that traditional tests cannot match.

Performance Assessment and Portfolios

Performance assessment was inspired in part by the perception that reductionist (e.g., CBM) and standardized testing approaches to assessment failed to capture constructivist, higher order thinking elements of student performance. Performance assessment developed in large part because of the premise that that which is tested is taught. Therefore, performance assessment advocates argued that educators needed tests worth teaching to (Wiggins, 1989). Performance assessment of complex, higher order academic achievement developed to assess complex, challenging academic skills, which in turn support school reforms (Glatthorn, Bragaw, Dawkins, & Parker, 1998) and teachers’ professional development (Stiggins & Bridgeford, 1984).

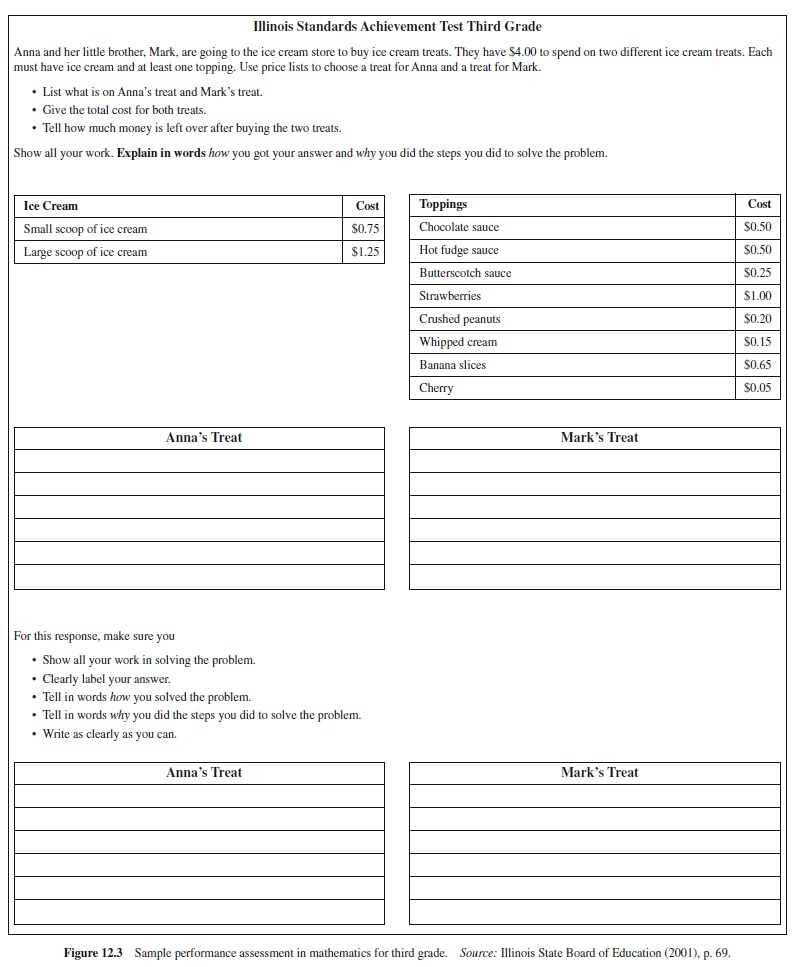

Performance assessment is characterized by complex tasks that require students to understand problems in context, accurately integrate and apply academic knowledge and skills to solve the problems, and communicate their problem-solving process and solutions via written, graphic, oral, and demonstrative exhibits (Braden, 1999). Performance assessments are characterized by tasks embedded in a problem-solving context that require students to construct responses, usually over an extended time frame, and that may require collaboration among group members. Scores produced by performance assessments are criterion referenced to levels of proficiency. An example of a mathematics performance assessment appears in Figure 12.3.

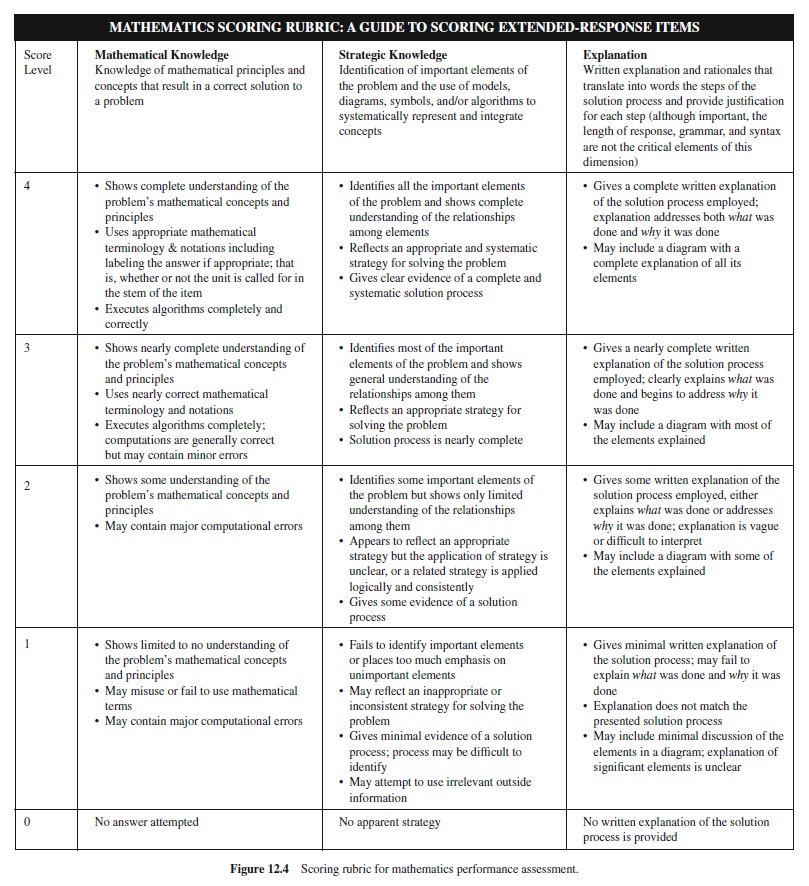

Scoring of performance assessments is a critical issue. Because responses are constructed rather than selected, it is not possible to anticipate all possible answers. Therefore, assessors use scoring guides called rubrics to judge responses against a criterion. Scores are generally rank ordered to reflect increasing levels of proficiency and typically contain four or five categories (e.g., Novice, Basic, Proficient, Advanced). Rubrics may be holistic (i.e., providing a single score for the response) or analytic (i.e., providing multiple scores reflecting various aspects of performance).An example of the rubric used to score the example mathematics performance assessment appears in Figure 12.4. Note that the rubric is analytic (i.e., it provides scores in more than one dimension) and can be used across a variety of grade levels and problems to judge the quality of student work. As is true of most rubrics, the sample rubric emphasizes conceptual aspects of mathematics, rather than simple computation or other low-level aspects of performance.