View sample psychological assessment in industrial/organizational settings research paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of psychology research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Context of Psychological Assessments in Industrial/Organizational Settings

Psychologists have been active in the assessment of individuals in work settings for almost a century. In light of the apparent success of the applications of psychology to advertising and marketing (Baritz, 1960), it is not surprising that corporate managers were looking for ways that the field could contribute to the solution of other business problems, especially enhancing worker performance and reducing accidents. For example, Terman (1917) was asked to evaluate candidates for municipal positions in California. He used a shortened form of the Stanford-Binet and several other tests and looked for patterns against past salary and occupational level (Austin, Scherbaum, & Mahlman, 2000). Other academic psychologists, notably Walter Dill Scott and Hugo Munsterberg, were also happy to oblige.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

In this regard, the approaches used and the tools and techniques developed clearly reflected prevailing thinking among researchers of the time. Psychological measurement approaches in industry evolved from procedures used by Fechner and Galton to assess individual differences (Austin et al., 2000). Spearman’s views on generalized intelligence and measurement error had an influence on techniques that ultimately became the basis of the standardized instruments popular in work applications. Similarly, if instincts were an important theoretical construct (e.g., McDougal, 1908), these became the cornerstone for advertising interventions. When the laboratory experimental method was found valuable for theory testing, it was not long before it was adapted to the assessment of job applicants for the position of street railway operators (Munsterberg, 1913). Vocational interest blanks designed for guiding students into careers were adapted to the needs of industry to select people who would fit in.

Centers of excellence involving academic faculty consulting with organizations were often encouraged as part of the academic enterprise, most notably one established by Walter Bingham at Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh (now Carnegie Mellon University). It makes sense, then, that programs such those at as Carnegie, Purdue, and Michigan State University were located in the proximity of large-scale manufacturing enterprises. As will become clear through a reading of this research paper, the legacy of these origins can still be seen in the models and tools of contemporary practitioners (e.g., the heavy emphasis on the assessment for the selection of hourly workers for manufacturing firms).

The practice of assessment in work organizations was also profoundly affected by activities and developments during the great wars fought by the United States. Many of the personnel and performance needs of the military during both the first and secondWorldWars were met by contributions of psychologists recruited from the academy. The work of Otis on the (then) new idea of the multiple-choice test was found extremely valuable in solving the problem of assessing millions of men called to duty for their suitability and, once enlisted, for their assignments to specific work roles. The Army’s Alpha test, based on the work of Otis and others, was itself administered to 1,700,000 individuals. Tools and techniques for the assessment of job performance were refined or developed to meet the needs of the military relative to evaluating the impact of training and determining the readiness of officers for promotion. After the war, these innovations were diffused into the private sector, often by officers turned businessmen or by the psychologists no longer employed by the government. Indeed, the creation of the Journal of Applied Psychology (1917) and the demand for practicing psychologists in industry are seen as outgrowths of the success of assessment operations in the military (Schmitt & Klimoski, 1991).

In a similar manner, conceptual and psychometric advances occurred as a result of psychology’s involvement in government or military activities involved in winning the second World War. Over 1,700 psychologists were to be involved in the research, development, or implementation of assessment procedures in aneffort to deal with such things as absenteeism, personnel selection, training (especially leader training), and soldier morale. Moreover, given advances in warfare technology, new problems had to be addressed in such areas as equipment design (especially the user interface), overcoming the limitations of the human body (as in high-altitude flying), and managing work teams. Technical advances in survey methods (e.g., the Likert scale) found immediate applications in the form of soldier morale surveys or studies of farmers and their intentions to plant and harvest foodstuffs critical to the war effort.

A development of particular relevance to this research paper was the creation of assessment procedures for screening candidates for unusual or dangerous assignments, including submarine warfare and espionage. The multimethod, multisource philosophy of this approach eventually became the basis for the assessment center method used widely in industry for selection and development purposes (Howard & Bray, 1988). Finally, when it came to the defining of performance itself, Flanagan’s (1954) work on the critical incident method was found invaluable. Eventually, extensions of the approach could be found in applied work on the assessment of training needs and even the measurement of service quality.

Over the years, the needs of the militaryand of government bureaus and agencies have continued to capture the attention of academics and practitioners, resulting in innovations of potential use to industry. This interplay has also encouraged the development of a large and varied array of measurement tools or assessment platforms. The Army General Classification test has its analogue in any number of multiaptitude test batteries. Techniques for measuring the requirements of jobs, like Functional Job Analysis or the Position Analysis Questionnaire, became the basis for assessment platforms like the GeneralAptitudeTest Battery (GATB) or, more recently, the Occupational Information Network (O*Net; Peterson, Mumford, Borman, Jeanneret, & Fleishman, 1999). Scales to measure job attitudes (Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969), organizational commitment (Mowday, Steers, & Porter, 1979), or work adjustment (Dawis, 1991) found wide application, once developed. Moreover, there is no shortage of standard measures for cognitive and noncognitive individual attributes (Impara & Plake, 1998).

Afinal illustration of the importance of cultural context on developments in industry can be found in the implementation of civil rights legislation in America in the 1960s and 1970s (and, a little later, the Americans with Disabilities Act). This provided new impetus to changes in theory, research designs, and assessment practices in work organizations.The litigation of claims under these laws has also had a profound effect on the kinds of measures found to be acceptable for use as well.

The Nature Ofassessment in Industrial and Organizational Settings

This research paper is built on a broad view of assessment relative to its use in work organizations. The thrust of the paper, much like the majority of the actual practice of assessment in organizations, will be to focus on constructs that imply or allow for the inference of job-related individual differences. Moreover, although we will emphasize the activities of psychologists in industry whenever appropriate, it should be clear at the outset that the bulk of individual assessments in work settings are being conducted by others—managers, supervisors, trainers, human resource professionals—albeit often under the guidance of practicing psychologists or at least using assessment platforms that the latter designed and have implemented on behalf of the company.

Most individuals are aware of at least some of the approaches used for individual assessment by psychologists generally. For example, it is quite common to see mention in the popularpressofpsychologists’useofinterviewsandquestionnaires. Individual assessment in work organizations involves many of these same approaches, but there are some characteristic features worth stressing at the outset. Specifically, with regard to assessments in work settings, we would highlight their multiple (and at times conflicting) purposes, the types of factors measured, the approach used, and the role that assessment must play to insure business success.

Purposes

Business Necessity

For the most part, assessments in work organizations are conducted for business-related reasons. Thus, they might be performed in order to design, develop, implement, or evaluate the impact of a business policy or practice. In this regard, the firm uses assessment information (broadly defined) to index such things as the level of skill or competency (or its obverse, their deficiencies) of its employees or their level of satisfaction (because this might presage quitting). As such, the information so gathered ends up serving an operational feedback function for the firm. It can also serve to address the issue of how well the firm is conforming to its own business plans (Katz & Kahn, 1978).

Work organizations also find it important to assess individuals as part of their risk management obligation. Most conspicuous is the use of assessments for selecting new employees (trying to identify who will work hard, perform well, and not steal) or in the context of conducting performance appraisals. The latter, in turn, serve as the basis for compensation or promotion decisions (Murphy & Cleveland, 1995; Saks, Shmitt, & Klimoski, 2000). Assessments of an individual’s level of work performance can become the (only) basis for the termination of employment as well. Clearly, the firm has a business need to make valid assessments as the basis for appropriate and defensible personnel judgments.

In light of the numerous laws governing employment practices in most countries (and because the United States, at least, seems to be a litigious society), assessments of the perceptions, beliefs, and opinions of the workforce with regard to such things as the prevalence of sexual harassment (Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfand, & Magley, 1997; Glomb, Munson, Hulin, Bergman, & Drasgow, 1999) or of unlawful discrimination are often carried out as part of management’s “due diligence” obligation. Thus, assessed attitudes can be used to complement demographic data supplied by these individuals relative to their race, age, gender, or disability and used in monitoring personnel practice and to insure nondiscriminatory treatment of the workforce (e.g., Klimoski & Donahue, 1997).

Individual Necessity

Individual assessments in industry can also be performed with the goal of meeting the needs of the individual worker as well. The assessment of individual training needs, once made, can become the basis for a specific worker’s training and development experiences. Such information would guide the worker to just what programs or assignments would best remedy a particular deficiency. Such data, if gathered regularly over time, can also inform the worker of his or her progress in skill acquisition. In a related manner, assessments may be gathered to guide the worker relative to a work career. Whether done in the context of an organizationally managed career-path planning program or done by the worker on his or her initiative, such competency assessments relative to potential future jobs or different careers are ultimately in the service of the worker.

Progressive firms and many others whose workers are covered by collective bargaining agreements might use individual assessment data to help workers find suitable employment elsewhere, a need precipitated by such things as a corporate restructuring effort or downsizing or as an outcome of an acquisition or a merger. Job pBibliography: and skills are typically evaluated as part of an outplacement program. Often, however, one is also assessed (and, if found wanting, trained) in such things as the capacity to look for different work or to do well in a job interview that might lead to new work.

Individual assessments are at the core of counseling and coaching in the workplace. These activities can be part of a larger corporate program for enhancing the capabilities of the workforce. However, usually an assessment is done because the individual worker is in difficulty. This may be manifested in a career plateau, poor job performance, excessive absenteeism, interpersonal conflict on the job, symptoms of depression, or evidence of substance abuse. In the latter cases such assessments may be part of an employee assistance program, specifically set up to help workers deal with personal issues or problems.

Research Necessity

Many work organizations and consultants to industry take an empirical approach to the design, development, and evaluation of personnel practices. In this regard, assessment data, usually with regard to an individual’s job performance, workrelated attitudes, or job-relevant behavior, are obtained in order to serve as research criterion measures. Thus, in evaluating the potential validity of a selection test, data regarding the performance of individuals on the test and their later performance on the job are statistically compared. Similarly, the impact of a new recruitment program may be evaluated by assessing such things as the on-the-job performance and work attitudes of those brought into the organization under the new system and comparing these to data similarly obtained from individuals who are stillbeing brought in under the old one. Finally, as another example, a proposed new course for training employees may need to be evaluated. Here, evidence of learning or of skill acquisition obtained from a representative sample of workers, both before and again after the program, might be contrasted with scores obtained from a group of employees serving as a comparison group who do not go through the training.

Assessments as Criterion Measures

In the course of almost one hundred years of practice, specialists conducting personnel research have concluded that good criterionmeasuresarehardtodevelop.Thismaybedueinpart to the technical requirements for such measures, as outlined in the next section. However, it also may be simply a reflection that the human attributes and the performances of interest are, by their very nature, quite complex. When it comes to criterion measures, this is most clearly noted in the fact that these almost always must be treated as multidimensional.

The notion of dimensionality itself is seen most clearly in measures of job performance. In this regard, Ghiselli (1956) distinguished three types of criterion dimensionality. He uses the term static dimensionality to convey the idea that at any point in time, we can imagine that there are multiple facets to performance. Most of us can easily argue that both quality and quantity are usually part of the construct. In order to define the effective performance of a manager, studies have revealed that it usually requires five or more dimensions to cover this complex role (Campbell, McCloy, Oppler, & Sager, 1993).

Dynamic dimensionality is the term used to capture the notion that the essence of effective performance can change over time, even for the same individual. Thus, we can imagine that the performance of a new worker might be anchored in such things a willingness to learn, tolerance of ambiguity, and persistence. Later, after the worker has been on the job for a while, he or she would be held accountable for such things as high levels of output, occasional innovation, and even the mentoring of other, newer, employees.

Finally, Ghiselli identifies the concept of individual dimensionality. In the context of performance measures, this is used to refer to the fact that two employees can be considered equally good (or bad), but for different reasons. One worker may be good at keeping a work team focused on its task, whereasanothermaybequiteeffectivebecauseheseemstobe able to manage interpersonal conflict and tension in the team so that it does not escalate to have a negative effect on team output. Similarly, two artists can be equally well regarded but for manifesting very different artistic styles.

An additional perspectives on the multidimensionality of performance is offered by Borman and Motowidlo (1993). In their model, task performance is defined as “activities that contribute to the organization’s technological core either directly by implementing a part of its technological process, or indirectly by providing it with needed materials or services” (p. 72). Task performance, then, involves those activities that are formally recognized as part of a job. However, there are many other activities that are important for organizational effectiveness that do not fall within the task performance category. These include activities such as volunteering, persisting, helping, cooperating, following rules, staying with the organization, and supporting its objectives (Borman & Motowidlo, 1993). Whereas task performance affects organizational effectiveness through the technical core, contextual performance does so through organizational, social, and psychological means. Like Ghisellis’s (1956) perspective, the task and contextual performance distinction (Borman & Motowidlo, 1993; Motowidlo, Borman, & Schmit, 1997; Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994) shows that the constructs we are assessing will vary depending on the performance dimension of interest. The multidimensionality of many of the constructs of interest to those doing individual assessments in industry places a major burden on those seeking to do highquality applied research. However, as will be pointed out below, it also has a profound on the nature of the tools and of the specific measures to be used for operational purposes as well.

Thus, assessments for purposes of applied research may not differ much in terms of the specific features of the tools themselves. For example, something as common as a work sample test may be the tool of choice to gather data for validation or for making selection decisions. However, when one is adopted as the source of criterion scores, it implies a requirement for special diligence from the organization in terms of assessment conditions, additional time or resources, and certainly high levels of skill on the part of the practitioner (Campbell, 1990).

Attributes Measured

As implied by the brief historical orientation to this research paper, the traditional focus on what to measure has been on those individual difference factors that are thought to account for worker success. These person factors are frequently thought of as inputs to the design and management of work organizations. Most often, the attributes to be assessed derive from an analysis of the worker’s job duties and include specific forms of knowledge, skills, abilities, or other attributes (KSAOs) implying work-related interests and motivation. More recently, the focus has been on competencies, the demonstrated capacity to perform job-relevant activities (Schippmann et al., 2000). Key competencies are ascertained from a careful consideration not of the job but of the role or functions expected to be performed by an employee if he or she is to contribute to business success. Thus, attributes such as speed of learning or teamwork skills might be the focus of assessments.As will be detailed later, these attributes might be the core of any personnel selection program.

Assessments of individuals in work settings may also focus on the process used by the employee to get the job done. Operationally, these are the kinds of behaviors that are necessary and must be carried out well in the work place if the worker is to be considered successful. These, too, derive from an analysis of the job and of the behaviors that distinguish effective employees from less effective ones. Process assessments are particularly common in organizational training and worker performance review programs.

For the most part, employees in work organizations are held accountable for generating products: outcomes or results. Thus, it is common for assessments to be focused on such things as the quality and quantity of performance, the frequency of accidents, and the number of product innovations proposed. The basis for such assessments might be a matter of record. Often, however, human judgment and skill are required in locating and categorizing work outcomes relative to some standard. Outcome assessments are often used as the basis for compensation and retention decisions. In the course of the year, most individuals in work organizations might be assessed against all three types of assessments.

Approaches Used for Assessment in Industry

Three features of the approach favored by many of those doing assessment work in industry are worth highlighting. The first has been noted already in that many assessment platforms are built on careful development and backed up by empirical evidence. Although it is possible that an assessment technique would be adopted or a particular practitioner hired without evidence of appropriateness for that particular organization, it is not recommended. As stressed throughout this research paper, to do so would place the firm at risk.

A second feature that is somewhat distinctive is that most assessments of individuals in work contexts are not done by psychologists. Instead, managers, supervisors, trainers, and even peers are typically involved in evaluating individuals on the factors of interest. This said, for larger firms, practicing psychologists may have had a hand in the design of assessment tools and programs (e.g., a structured interview protocol for assessing job applicants), or they may have actually trained company personnel on how to use them. However, the assessments themselves are to be done by the latter without much supervision by program designers. For smaller firms, this would be less likely, because a practicing psychologist might be retained or used on an as-needed basis (e.g., to assist in the selection of a managing partner in a law firm). Under these circumstances, it would be assumed that the psychologist would be using assessment tools that he or she has found valid in other applications.

A final distinction between assessment in industry and other psychological assessments is that quite often assessments are being done on a large number of individuals at the same time or over a short period of time. For example, when the fire and safety service of Nassau County, NewYork sought to recruit and select about 1,000 new police officers, it had to arrange for 25,000 applicants to sit for the qualifying exam at one time (Schmitt, 1997). This not only has implications for the kinds of assessment tools that can be used but affects such mundane matters as choice of venue (in this case, a sports arena was needed to accommodate all applicants) and how to manage test security (Halbfinger, 1999).

The large-scale nature of assessments in industry implies the common use of aggregate data. Although the individual case will be the focus of the assessment effort, as noted earlier, very often the firm is interested in averages, trends, or establishing the existence of reliable and meaningful differences on some metric between subgroups. For example, individual assessments of skill might be made but then aggregated across cases to reveal, for example, that the average skill of new people hired has gone up as a result of the implementation of a new selection program. Similarly, the performance of individuals might be assessed to show that the mean performance level of employees under one manager is or is not better than the mean for those working under another. Thus, in contrast to other venues, individual assessments conducted in work settings are often used as a means to assess still other individuals, in this case, organizational programs or managers.

Marketplace and the Business Case

Most models of organizational effectiveness make it clear that the capacity to acquire, retain, and efficiently use key resources is essential. In this regard, employees as human resources are no different. At the time that this research paper is being prepared, unemployment levels are at historical lows in the United States. Moreover, given the strength of the so-called new economy, the demand for skilled workers is intense. Added to the convergence of these two marketplace realities is the arrival of new and powerful Internet-based services that give more information than ever to current and prospective employees regarding the human resource needs and practices of various organizations. It is important to note that similar services now provide individuals with a more accurate sense of their own market value than ever. Clearly there are intense competitive pressures to recruit, select, and retain good employees. Those responsible for the design and management of platforms for individual assessment must contribute to meeting such pressures or they will not be retained.

Another marketplace demand is for efficiency. The availability of resources notwithstanding, few organizations can escape investor scrutiny with regard to their effective use of resources. When it comes to assessment programs, this implies that new approaches will be of interest and ultimately found acceptable if it can be demonstrated that (a) they address a business problem, (b) they add value over current approaches, and (c) they have utility, in the sense that the time and costs associated with assessment are substantially less than the gains realized in terms of worker behavior (e.g., quitting) or performance. In fact, the need to make a business case is a hallmark of the practice of individual assessments in work organizations. It is also at the heart of the notion of utility as described in the next section.

A third imperative facing contemporary practitioners is embedded in the notion speed to market. All other things considered, new and useful assessment tools or programs need to be brought on line quickly to solve a business problem (e.g., meeting the human resource needs for a planned expansion or reducing high levels of turnover). Similarly, the information on those individuals assessed must be made available quickly so that decisions can be made in a timely manner. These factors may cause an organization to choose to make heavy use of external consultants for assessment work in the context of managing their human resource needs and their bottom line.

In summary, individual assessment in work settings is indeed both similar to and different from many other contexts in which such assessments take place. Although the skills and techniques involved would be familiar to most psychologists, the application of the former must be sensitive and appropriate to particular contextual realities.

Professional and Technical Considerations

As described in the overview section, professionals who conduct assessments in industrial settings do so based on the work context. A job analysis provides information on the tasks, duties, and responsibilities carried out by the job incumbents as well as the KSAOs needed to perform the job well (Saks et al., 2000). Job analysis information helps us conduct selection and promotion assessments by determining if there is a fit between the skills needed for the job and those held by the individual and if the individual has the potential to perform well on the important KSAOs. We can also use job analysis information for career management by providing the individual and the career counselor or coach with information about potential jobs or careers. The individual can then be assessed using various skill and interest inventories to determine fit. Job analysis information can also be used for classification and placement to determine which position within an organization best matches the skills of the individual.We will discuss the purpose, application, and tools for assessments in the next section. In this section, we will focus on how organizations use job analysis tools to develop assessment tools to make organizational decisions.

The Role of Assessment Data for Inferences in Organizational Decisions

Guion (1998) points out that one major purpose of research on assessments in industrial/organizational settings is to evaluate how well these assessments help us in making personnel decisions. The process he describes is prescriptive and plays out especially well for selection purposes. The reader should be aware that descriptively there are several constraints, such as a small number of cases, the rapid pace at which jobs change, and the time it takes to carry out the process, that make this approach difficult. Guion therefore suggests that assessment practices should be guided by theory, but so too should practice inform theory. With that said, his approach for evaluating assessments is described below:

- Conduct a job and organizational analysis to identify what criterion we are interested in predicting and to provide a rational basis for specifying which applicant characteristics (predictors) are likely to predict that criterion.

- Choose the specific criterion or criteria that we are trying to predict. Usually, the criteria are some measure of performance (e.g., production quality or earnings) or some valued behavior associated with the job (e.g., adaptability to change).

- Developthepredictivehypothesisbasedonstrongrationale and prior research.

- Select the methods of measurement that effectively assess the construct of interest. Guion suggests that we should not limit our assessments to any particular method but that we shouldlookatothermethods.Thetendencyhereistoassess candidatesontraitsforwhichtestsaredevelopedratherthan to assess them on characteristics not easily assessed with current testing procedures (Lawshe, 1959).

- Design the research to assure that findings from research samples can generalize to the population of interest, job applicants.

- Collect data using standardized procedures and the appropriate treatment of those being assessed.

- Evaluate the results to see if the predictor correlates with the criterion of interest. This evaluation procedure is often called validation.

- Justify the selection procedure through the assessment of both incremental validity and utility. The former refers to the degree to which the proposed selection procedure significantly predicts the criterion over and above a procedure already in place. The latter refers to the economic value of utilizing the new procedure.

Technical Parameters

Reliability

Most readers are aware of the various forms of reliability and how they contribute to inferences in assessments. This section will note the forms of reliability used in industrial settings.

For the most part, organizations look at internal consistency reliability more than test-retest or parallel forms. In many industrial settings, with the exception of large organizations that conduct testing with many individuals on a regular basis, it is often asserted that time constraints limit the evaluation of the latter forms of reliability.

The kind of reliability sought should be appropriate to the application of the assessment. Of particular importance to industrial settings are retest reliability and interrater reliability. For example, in the context of structured interviews or assessment centers, if raters (or judges) do not agree on an individual’s score, this should serve as a warning that the assessment platform should be reviewed. Moreover, political issues may come into play if one of the raters has a significant position of power in the organization. This rater may want the person to be selected even if other raters disagree.

Validity

All test validation involves inferences about psychological constructs (Schmitt & Landy, 1993). It is not some attribute of the tests or test items themselves (e.g., Guion, 1980).

We are not simply interested in whether an assessment predicts performance, but whether the inferences we make with regard to these relationships are correct. Binning and Barrett (1989) lay out an approach for assessing the validity (job-relatedness of a predictor) of personnel decisions based on the many inferences we make in validation.

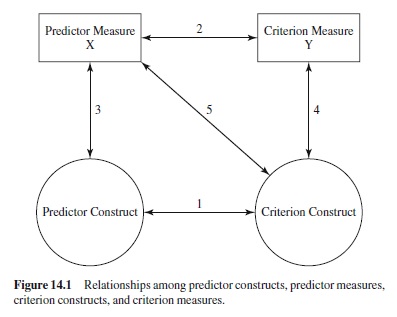

Guion’s (1998) simplification of Binning and Barrett’s presentation is described in Figure 14.1 to illustrate the relationships among predictor constructs, predictor measures, criterion constructs, and criterion measures.

Line 1 shows that the relationship between the predictor construct (e.g., conscientiousness) is related to the criterion construct (some form of job behavior such as productivity) or a result of the behavior. Relationship 2 is the only inference that is empirically testable. It is the statistical relationship between the predictor measure, a test of conscientiousness such as the Hogan Personality Inventory (HPI; R. T. Hogan & Hogan, 1995), and the criterion measure (some measured criteria of job performance such as scores on a multisource feedback assessment). Tests of inferences 3 and 4 are used in construct validation. Relationship 3 shows whether the predictor measure (HPI) is a valid measure of the predictor construct (conscientiousness). Relationship 4 assesses whether the criterion measure (multisource feedback scores) is effectively measuring the performance of interest (e.g., effective customer service). Finally, relationship 5 is the assessment of whether the predictor measure (conscientiousness) is related to the criterion construct of interest (customer service) in a manner consistent with its presumed relationship to the criterion measure. Relationship 5 is dependent on the inferences we make about our job analysis data and those that we make about our predictor and construct relationships. Although the importance of establishing construct validity is now well established in psychology, achieving the goal of known construct validity in the assessments used in work contexts continues to be elusive.

Political considerations come into play in establishing validity in industrial settings. Austin, Klimoski, and Hunt (1996) point out that “validity is necessary but not sufficient for effective long-term selection systems.” They suggest that in addition to the technical considerations discussed above, procedural justice or fairness and feasibility-utility also be considered. For example, in union environments optimizing all three standards may be a better strategy than maximizing one set.

Fairness

Industrial/organizational psychologists view fairness as a technical issue (Cascio, 1993), a social justice issue (Austin et al., 1996), and a public policy issue (American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, 1999). In industrial/organizational settings, the technical issues of differential validity and differential prediction are assessed for fairness. Differential validity exists when there are differences in subgroup validity coefficients. If a measure that is valid only for one subgroup is used for all individuals regardless of group membership, then the measure may discriminate unfairly against the subgroup for whom it is invalid. Job performance and test performance must be considered because unfair discrimination cannot be said to exist if unfair test performance is associated with inferior job performance by the same group. Differential prediction exists when there are slope and intercept differences between minority and nonminority groups. For example, Cascio (1993) points out that a common differential prediction exists when the prediction system for the nonminority group slightly overpredicts minority group performance. In this case, minorities would tend not to do as well on the job as their test scores would indicate.

As Austin et al. (1996) point out, fairness is also related to the social justice of how the assessment is administered. For example, they point out that that perceptions of neutrality of decision makers, respect given to test takers, and trust in the system are important for the long-term success of assessments. In fact, Gilliland (1993) argues that procedural justice can be decomposed into three components: formal characteristics of procedures, the nature of explanations offered to stakeholders, and the quality of interpersonal treatment as information comes out. These issues must be considered for there to be acceptability of the process.

Additionally, it cannot be stressed enough that there is no consensus on what is fair. Fairness is defined in a variety of ways and is subject to a several interpretations (American Educational ResearchAssociation et al., 1999). Cascio (1993) points out that personnel practices, such as testing, must be considered in the total system of personnel decisions and that each generation should consider the policy implications of testing. The critical consideration is not whether to use tests but, rather, how to use tests (Cronbach, 1984).

Feasibility/Utility

This term has special meaning in the assessment of individuals in industry. It involves the analysis of the interplay among the predictive power of assessment tools and the selection ratio. In general, even a modest correlation coefficient can have utility if there is a favorable selection ratio. Assessments in this context must be evaluated against the cost and potential payoff to the organization. Utility theory does just that. It provides decision makers with information on the costs, benefits, and consequences of all assessment options. For example, through utility analysis, an organization can decide whether a structured interview or a cognitive ability test is more cost effective. This decision would also be concerned with the psychometric properties of the assessment. Cascio (1993) points out the importance of providing the utility unit (criteria) in terms that the user can understand, be it dollars, number of products developed, or reduction in the number of workers needed. Because assessment in industry must concern itself with the bottom line, costs and outcomes are a critical component in evaluating assessment tools.

Robustness

In selecting an assessment, it is also important to assess whether its validity is predictive across many situations. In other words, is the relationship robust?The theory of situation specificity is based on the findings of researchers that validities for similar jobs in different work environments varied significantly. With the increased emphasis on metaanalysis and validity generalization (Schmidt & Hunter, 1977; Schmidt et al., 1993), many researchers believe that these differences were due to statistical and measurement artifacts and were not real differences between jobs.

Legal Considerations

Employment laws exist to prohibit unfair discrimination in employment and provide equal employment opportunity for all. Unfair discrimination occurs when employment decisions are based on race, sex, religion, ethnicity, age, or disability rather than on job-relevant knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (U.S. Department of Labor, 1999). Employment practices that unfairly discriminate against people are called unlawful or discriminatory employment practices.

Those endeavoring to conduct individual assessments in industry must consider the laws that apply in their jurisdiction. With the increasingly global society of practitioners, they must also consider laws in other countries. In the United States, case law and professional standards and acts must be followed. The following are some standards and acts that must be considered:

- Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (as amended in 1972), which prohibits unfair discrimination in all terms and conditions of employment based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.

- Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA), which prohibits discrimination against employees or applicants age 40 or older in all aspects of the employment process.

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) of 1972, which is responsible for enforcing federal laws prohibiting employment discrimination.

- Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedures of 1978 (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Civil Service Commission, U.S. Department of Labor, & U.S. Department of Justice, 1978), which incorporate a set of principles governing the use of employee selection procedures according to applicable laws and provide a framework for employers to determine the proper use of tests and other selection procedures. A basic principle of the guidelines is that it is unlawful to use a test or selection procedure that creates adverse impact, unless justified. When there is no charge of adverse impact, the guidelines do not require that one show the job-relatedness of assessment procedures; however, they strongly encourage one to use only job-related assessment tools. Demonstrating the job-relatedness of a test is the same as establishing that the test may be validly used as desired. Demonstrating the business necessity of an assessment involves showing that its use is essential to the safe and efficient operation of the business and that there are no alternative procedures available that are substantially equally valid to achieve business results with lesser adverse impact.

- Title I of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, which specifically requires demonstration of both job-relatedness and business necessity (as described in the previous section). The business necessity requirement is harder to satisfy than the “business purpose test” suggested earlier by the Supreme Court. The act also prohibits score adjustments, the use of different cutoff scores for different groups of test takers, or the alteration of employment-related tests based on the demographics of test takers.

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA), which requires that qualified individuals with disabilities be given equal opportunity in all aspects of employment. Employers must provide reasonable accommodation to persons with disabilities when doing so would not pose undue hardship.

- Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (American Educational Research Association et al., 1999) and principles for validation and use of Personnel Selection Procedures (1987), which are useful guidelines for individuals developing, evaluating, and using assessments in employment, counseling, and clinical settings. Even though they are guidelines, they are consistent with applicable regulations.

Purpose, Focus, and Tools for Assessment in Industrial/Organizational Settings

This section will describe how assessments in industrial/organizational settings are used, the focus of those assessments and the major tools used to conduct these assessments. The reader may notice that the focus of the assessment may be similar for different assessment purposes.

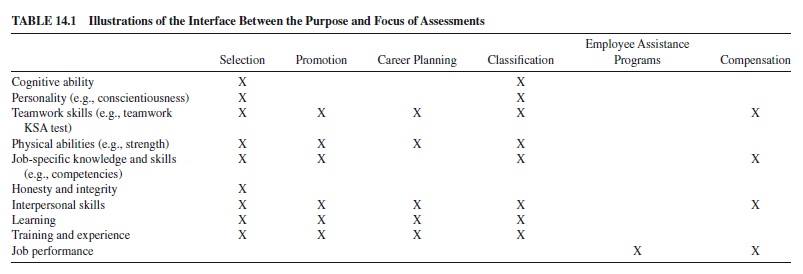

For example, cognitive ability may be the focus of both a selection test and a career planning assessment. Table 14.1 provides the linkage of these components and can serve as a preview of the material to follow.

Purpose of Assessment in Industry

Selection

Selection is relevant to organizations when there are more qualified applicants than positions to be filled. The organization must decide who among those applicants can perform best on the job and should therefore be hired. That decision is based upon the prediction that the person hired will be more satisfactory than the person rejected (Cascio, 1993). The goal of selection is thus to capitalize on individual differences in order to select those persons who possess the greatest amount of particular characteristics judged important for job success. Aparticular assessment is chosen because it looks as though it may be a valid measure of the attributes that are important for a particular job (Landy, 1989; Saks et al., 2000). One or more predictors are selected that presumably relate to the criteria (performance on the job). These predictor constructs become the basis for an assessment test. For example, if we identified that cognitive ability is an important predictor for performance in the job of customer service representative, then we would develop a test that measures the construct of cognitive ability.

The use of assessment tools for selection varies depending on the job performance domain and the level of individual we are selecting. For example, because routine work (e.g., assembly line) is more structured than novel work (e.g., consulting) and because teamwork requires more interpersonal skills than does individually based work, selection assessments vary greatly for different jobs. Additionally, the level of the position dictates the type of assessment we would use. Selection for a chief executive officer would probably involve several interviews, whereas selection for a secretary might involve a typing test, an interpersonal skills test, and an interview.

Thus, selection in industrial settings varies depending on the context in which it is used. Regardless of this difference, the Uniform Guidelines and Standards for Educational and Psychological Assessment should always be applied.

Promotion

When we are conducting an assessment of performance, we are generally determining an individual’s achievement at the time of the assessment. However, when we are considering an individual for a promotion, performance can be the basis for inferring his or her potential to perform a new job. However, we often try to directly assess traits or qualities thought to be relevant to the new job in practice.

In the context of school, an achievement test would be a final examination. At work, it might be a work sample or job knowledge test (more on these types of tests follows) or multisource feedback on the individual’s performance over the past year on the job. In the context of school, an assessment of potential might be the Standardized Aptitude Test, which determines the person’s potential to perform well in college (Anastasi & Urbina, 1996). At work, an assessment might focus on managerial potential and on sales potential (e.g., J. Hogan & Hogan, 1986). These scales have been shown to predict performance of managers and sales representatives, respectively. Additionally, assessment centers and multisource assessment platforms are methods for assessing an individual’s potential for promotion.

One challenge faced by psychologists in developing promotion instruments is that we are often promoting individuals based on past performance; however, often a new job requires additional KSAOs. This occurs when an individual is moving from a position in the union to one in management, from being a project member to being a project manager, or into any position requiring new skills. In this situation, the assessment should focus on future potential rather than simply past performance.

Another challenge in the promotion arena is that organizations often intend to use yearly performance appraisals to determine if a candidate should be promoted. However, there is often little variance between candidates on these appraisals. Many raters provide high ratings, often to insure workplace harmony, therefore showing little difference between candidates. Other tools, which involve the use of multiple, trained raters used in conjunction with the performance appraisal, might be used to remedy this problem.

Career Planning

Career planning is the process of helping individuals clarify a purpose and a vocation, develop career plans, set goals, and outline steps for reaching those goals.Atypical career plan includes identification of a career path and the skills and abilities needed to progress in that path (Brunkan, 1991). It involves assessment, planning, goal setting, and strategizing to gain the skills and abilities required to implement the plan. It can be supported by coaching and counseling from a psychologist or from managers and human resources (HR) specialists within a company. Assessments for the purpose of career planning would be conducted so that individuals can have a realistic assessment of their own potential (Cascio, 1991) as well as theirvalues, interests, and lifestyles (Brunkan, 1991). Assessments for this purpose include the Strong Occupational Interest Blank (Hansen, 1986) and Holland’s Vocational PBibliography: Inventory (Holland, Fritsche, & Powell, 1994). Additionally, the results of participation in an assessment center (described later) or a multisource feedback instrument might be shared with an employee to identify those areas on which he or she could develop further.

Career management in organizations can take place from the perspective of the individual or the firm. If it is the former, the organization is concerned with ensuring that the individual develops skills that are relevant to succeeding in the firm and adding value as he or she progresses. If it is the latter, the individual seeks to develop skills to be applied either inside or outside of the organization. Additionally, the size of the firm and its stability will dictate the degree to which assessments for the purpose of career management can occur. We would be more likely to see large government organizations focusing on career development than small start-up firms.

Training is often a large part of career planning because it facilitates the transfer of skills that are necessary as the individual takes on new tasks. Assessments in this context are used to see if people are ready for training. A representative part of the training is presented to the applicant (Saks et al., 2000) to see if the applicant is ready for and likely to benefit from the training. Additionally, Noe and Schmitt (1986) have found that trainee attitudes and involvement in careers affected the satisfaction and the benefit from training. They show that understanding of trainee attitudes might benefit the organization so that it can develop interventions (e.g., pretraining workshops devoted to increasing involvement and job commitment of trainees) to enhance the effectiveness of the training program.

Classification

Assessments can also be used to determine how to best use staff.The results of an assessment might provide management with knowledge of the KSAOs of an individual and information on his or her interests. Classification decisions are based upon the need to make the most effective matching of people and positions. The decision maker has a specified number of available positions on one hand and a specific number of people on the other.

Depending on the context, the firm might take the perspective that the firm’s needs should be fulfilled first or, if the individual is critical to the firm, that his or her needs should dictate where he or she is placed. In the former case, the organization would place an individual in an open slot rather than in a position where he or she may perform better or wish to work. The individual is placed there simply because there is an immediate business need. The organization knows that this individual can perform well, but he or she may not be satisfied here. On the other hand, organizations may have the flexibility to put the individual in a position he or she wants so that job satisfaction can be increased. Some organizations provide so-called stretch assignments, which allow individuals to learn new skills. Although the organization is taking a risk with these assignments, the hope is that the new skills will increase job satisfaction and also add value to the firm in the future.

Employee Assistance Programs

Many organizations use assessments as part of employee assistance programs (EAPs). Often these programs are viewed as an employee benefit to provide employees with outlets for problems that may affect their work. Assessments are used to diagnose stress- or drug-related problems. The individual might be treated through the firm’s EAP or referred to a specialist.

Compensation

Organizations also assess individuals to determine their appropriate compensation. A traditional method is to measure the employee’s job performance (job-based compensation). More recently, some organizations are using skill-based pay systems, according to which individuals are compensated on explicitly defined skills deemed important for their organization. Murray and Gerhart (1998) have found that skill-based systems can show greater productivity.

Focus of Assessments in Industry

The focus of assessments in industrial settings involves a number of possible constructs. In this section, we highlight those constructs that are robust and are referenced consistently in the literature.

Cognitive Ability Tests

The literature has established that cognitive ability, and specifically general mental ability, is a suitable predictor of many types of performance in the work setting. The construct of cognitive ability is generally defined as the “hypothetical attributes of individuals that are manifest when those individuals are performing tasks that involve the active manipulation of information” (Murphy, 1996, p. 13). Many agree with the comment of Ree and Earles (1992) that “If an employer were to use only intelligence tests and select the highest scoring applicant for the job, training results would be predicted well regardless of the job, and overall performance from the employees selected would be maximized” (p. 88). The metaanalysis conducted by Schmidt and Hunter (1998) showed that scores on cognitive ability measures predict task performance for all types of jobs and that general mental ability and a work sample test had the highest multivariate validity and utility for job performance.

Additionally, the work conducted for the Army Project A has shown that general mental ability consistently provides the best prediction of task proficiency (e.g., McHenry, Hough, Toquam, Hanson, & Ashworth, 1990). The evidence for this relationship is strong. For example, the meta-analysis of Hunter and Hunter (1984) showed that validity for general mental ability is .58 for professional-managerial jobs, .56 for high-level complex technical jobs, .51 for medium-complexity jobs, .40 for semiskilled jobs, and .23 for unskilled jobs. Despite these strong correlations, there is also evidence that it is more predictive of task performance (formally recognized as part of the job) than of contextual performance (activities such as volunteering, persisting, cooperating).

Personality

As we expand the criterion domain (Borman & Motowidlo, 1993) to include contextual performance, we see the importance of personality constructs. Although there is controversy over just how to define personality operationally (Klimoski, 1993), it is often conceptualized as a dynamic psychological structure determining adjustment to the environment but manifest in the regularities and consistencies in the behavior of an individual over time (Snyder & Ickes, 1985).

Mount and Barrick (1995) suggest that the emergence of the five-factor structure of personality led to empirical research that found “meaningful and consistent” relationships between personality and job performance. Over the past 15 years, researchers have found a great deal of evidence to support the notion that different components of the five-factor model (FFM; also known as the “Big Five”) predict various dimensions of performance. Although the FFM is prevalent at this time, it is only one of many personality schema. Others include the 16 Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF; Cattell, Cattell, & Cattell, 1993) and a nine-factor model (Hough, 1992).

The components of the FFM are agreeableness, extroversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Research has shown that these factors predict various dimensions of job performance and therefore are useful constructs to assess in selection. McHenry et al. (1990) found that scores from ability tests provided the best prediction for job-specific and general task proficiency (i.e., task performance), whereas temperament or personality predictors showed the highest correlations with such criteria as giving extra support, supporting peers, and exhibiting personal discipline (i.e., contextual performance).

The factor of personality that has received the most attention is conscientiousness. For example, Mount and Barrick (1995) conducted a meta-analysis that explored the relationship between conscientiousness and the following performance measures: overall job performance, training proficiency, technical proficiency, employee reliability, effort, quality, administration, and interpersonal orientation. They found that although conscientiousness predicted overall performance (both task and contextual), its relationships with the specific criterion determined by motivational effort (employee reliability and effort) were stronger. Organ and Ryan (1995) conducted a metaanalysis on the predictors of organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). They found significant relationships between conscientiousness and the altruism component of OCBs (altruism represents the extent to which an individual gives aid to another, such as a coworker). Schmidt and Hunter’s (1998) recent meta-analysis showed a .31 correlation between conscientiousness and overall job performance. They concluded that, in addition to general mental ability and job experience, conscientiousness is the “central determining variable of job performance” (p. 272).

The FFM of personality has also been shown to be predictive of an individual’s performance in the context of working in a team (we will discuss this issue in the next section). For example, a meta-analysis conducted by Mount, Barrick, and Stewart (1998) found that conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability were positively related to overall performance in jobs involving interpersonal interactions. Emotional stability and agreeableness were strongly related to performance in jobs that involve teamwork.

Teamwork Skills

Individuals working in organizations today are increasingly finding themselves working in teams with other people who have different sets of functional expertise (Hollenbeck, LePine, & Ilgen, 1996). This change from a clearly defined set of individual roles and responsibilities to an arrangement in which the individual is required to exhibit both technical expertise and an ability to assimilate quickly into a team is due to the speed and amount of information entering and exiting an organization. No individual has the ability to effectively integrate all of this information. Thus, teams have been introduced as a solution (Amason, Thompson, Hochwarter, & Harrison, 1995).

Although an organization is interested in overall team performance, it is important to focus on the individuals’ performance within the team (individual-in-team performance) so that we know how to select and appraise them. Hollenbeck et al. (1996) point out that certain types of individuals will assimilate into teams more easily than others. It is these individuals that we would want to select for a team. In the case of individual-in-team performance, we would suggest that both a contextual and ateamwork analysis be conducted.The contextual analysis provides the framework for team staffing by looking at, first, the reason for selection, be it to fill a vacancy, staff a team, or to transform an organization from individual to team-based work, and, second, the team’s functions (as described by Katz & Kahn, 1978), be they productive/technical, related to boundary management, adaptive, maintenance-oriented, or managerial/executive. Additionally, the team analysis focuses on the team’s role, the team’s division of labor, and the function of the position. The results have implications for the KSAOs needed for the job (Klimoski & Zukin, 1998).

Physical Abilities

Physical abilities are important for jobs in which strength, endurance, and balance are important (Guion, 1998), such as mail carrier, power line repairer, and police officer. Fleishman and Reilly (1992) have developed a taxonomy of these abilities. Measures developed to assess these abilities have predicted work sample criteria effectively (R. T. Hogan, 1991). However, they must be used with caution because they can cause discrimination. The key here is that the level of that ability must be job relevant. Physical ability tests can only be used when they are genuine prerequisites for the job.

Job-Specific Knowledge and Skill

The O*NET system of occupational information (Peterson, Mumford, Borman, Jeanneret, & Fleishman, 1995) suggests that skills can be categorized as basic, cross-functional, and occupational specific. Basic skills are developed over a long period of time and provide the foundation for future learning. Cross-functional skills are useful for a variety of occupations and might include such skills as problem solving and resource management. Occupational (or job-specific) skills focus on those tasks required for a specific occupation. It is not surprising that research has shown that job knowledge has a direct effect on one’s ability to do one’s job. In fact, Schmidt, Hunter, and Outerbridge’s (1986) path analysis found a direct relationship between job knowledge and performance. Cognitive ability had an indirect effect on performance through job knowledge. Findings like this suggest that under certain circumstances job knowledge may be a more direct predictor of performance than cognitive ability.

Honesty and Integrity

The purpose of honesty/integrity assessments is to avoid hiring people prone to counterproductive behaviors. Sackett, Burris, and Callahan (1989) classify the measurement of these constructs into two types of tests. The first type is overt tests, which directly assess attitudes toward theft and dishonesty.They typically have two sections. One deals with attitudes toward theft and other forms of dishonesty (beliefs about the frequency and extent of employee theft, perceived ease of theft, and punitiveness toward theft). The other deals with admissions of theft. The second type consists of personality-based tests, which are designed to predict a broad range of counterproductive behaviors such as substance abuse (Ones & Viswesvaran, 1998b; Camera & Schneider, 1994).

Interpersonal Skills

Skills related to social perceptiveness include the work by Goleman (1995) on emotional intelligence and works on social intelligence (e.g., M. E. Ford & Tisak, 1982; Zaccaro, Gilbert, Thor, & Mumford, 1991). Goleman argues that empathy and communication skills, as well as social and leadership skills, are important for success at work (and at home). Organizations are assessing individuals on emotional intelligence for both selection and developmental purposes. Another interpersonal skill that is used in industrial settings is social intelligence, which is defined as “acting wisely in human relations” (Thorndike, 1920) and one’s ability to “accomplish relevant objectives in specific social settings” (M. E. Ford & Tisak, 1983, p. 197). In fact, Zaccaro et al. (1991) found that social intelligence is related to sensitivity to social cues and situationally appropriate responses. Socially intelligent individuals can better manage interpersonal interactions.

Interests

Psychologists in industrial settings use interests inventories to help individuals with career development. Large organizations going through major restructuring may have new positions in their organization. Interests inventories can help individuals determine what new positions might be a fit for them (although they may still have to develop new skills to succeed in the new positions). Organizations going through downsizing might use these inventories as part of their outplacement services.

Learning

Psychologists in industry also assess one’s ability to learn or the information that one has learned. The former might be assessed for the purpose of determining potential success in a training effort or on the job (and therefore for selection). As mentioned earlier in this research paper, the latter might be assessed to determine whether individuals learned from attending a training course. This information helps the organization to determine whether a proposed new course should be used for a broader audience. Tools used to assess learning can range from knowledge tests to cognitive structures or to behavioral demonstration of competencies under standardized circumstances (J. K. Ford, 1997).

Training and Experience

Organizations often use training and experience information to determine if the individual, based on his or her past, has the KSAOs necessary to perform in the job of interest. This information is mostly used for selection. An applicant might describe his or her training and experience through an application form, a questionnaire, a resume, or some combination of these.

Job Performance

Job performance information is frequently used for compensation or promotion decisions, as well as to refer an individual to an EAP (if job performance warrants the need for counseling). In these situations, job performance is measured to make personnel decisions for the individual. In typical validation studies, job performance is the criterion, and measures discussed above (e.g., training and experience, personality, cognitive ability) are used as predictors.

Tools

Cognitive Ability Tests

Schmidt and Hunter (1998) conducted a meta-analysis of measures used for hiring decisions.They have found that cognitive ability tests (e.g., Wonderlic Personnel Test, 1992) are robust predictors of performance and job-related learning.

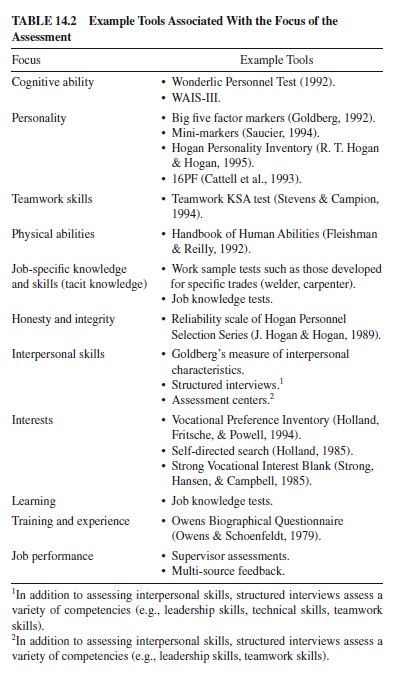

They argue that because cognitive ability is so robust, it should be referred to as a primary measure for hiring decisions and that other measures should be referred to as supplementary measures. Where the information is available, this section will summarize these measures and some of their findings on the incremental validity of these measures in predicting performance. Additionally, the reader we suggest that the reader refer to Table 14.2 for examples of tools linked to each type of assessment.

Personality Assessments

Several tools are available to measure personality. Some focus on the FFM of personality (e.g., Big Five Factor Markers, Goldberg, 1992; Mini-markers, Saucier, 1994; Hogan Personality Inventory; R. T. Hogan & Hogan, 1995), whereas others focus on a broader set of personality characteristics (e.g., 16PF; Cattell et al., 1993).

Teamwork Skills Assessments

Several industrial/organizational psychologists have investigated those knowledges, skills, and abilities (KSAs) and personality dimensions that are important for teamwork. For example, Stevens and Campion (1994) studied several teams and argued that two major categories of KSAs are important for teamwork: interpersonal KSAs and self-management KSAs. Research by Stevens and Campion has shown that that teamwork KSAs (to include interpersonal KSAs and self-management KSAs) predict on-the-job teamwork performance of teams in a southeastern pulp processing mill and a cardboard processing plant. Steve and Campion’s teamwork KSAs are conflict resolution, collaborative problem solving, communication, goal setting and performance management, planning, and task coordination.

Physical Abilities Tests

In jobs such as those of police officer, fire fighter, and mail carrier, physical strength (e.g., endurance or speed) is critical to job performance. Therefore, tools have been developed to assess the various types of physical abilities. Fleishman and Reilly’s (1992) work in this area identifies nine major physical ability dimensions along with scales for the analysis of job requirements for each of these dimensions that are anchored with specific examples.

Tools to Measure Job-Specific Knowledge and Skill

Work sample tests are used to measure job-specific knowledge and skill. Work sample tests are hands-on job simulations that must be performed by applicants. These tests assess one’s procedural knowledge base. For example, as part of a work sample test, an applicant might be required to repair a series of defective electric motors. Often used to hire skilled workers such as welders and carpenters (Schmidt & Hunter, 1998), these assessments must be used with applicants who already know the job. Schmidt and Hunter found that work sample tests show a 24% increase in validity over that of cognitive ability tests. Job knowledge tests are also used to assess job-specific knowledge and skills. Like work sample tests, these assessments cannot be used to hire or evaluate inexperienced employees. They are often constructed by the hiring organization on the basis of a job analysis.Although they can be developed internally, this is often costly and time-consuming. Those purchased off the shelf are less expensive and have only slightly lower validity than those developed by the organization. Job knowledge tests increase the validity over cognitive ability measures by 14%.

Honesty and Integrity Tests

Schmidt and Hunter (1998) found that these types of assessments show greater validity and utility than do work samples. The reliability scale of the Hogan Personnel Selection Series (J. Hogan & Hogan, 1989) is designed to measure “organizational delinquency” and includes items dealing with hostility toward authority, thrill seeking, conscientiousness, and social insensitivity. Ones, Viswesvaran, and Schmidt (1993) found that integrity tests possess impressive criterion-related validity. Both overt and personality-based integrity tests correlated with measures of broad counterproductive behaviors such as violence on the job, tardiness, and absenteeism. Reviews of validity of these instruments show no evidence of adverse impact against women or racial minorities (Sackett et al., 1989; Sackett & Harris, 1984).

Assessments of Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal skills are often found in the results of job analyses or competency studies. Therefore, an organization might assess interpersonal skills in an interview by asking the candidate to respond to questions on how they handled past experiences dealing with difficult interpersonal interactions. They might also be assessed through assessment centers by being placed in situations like the leaderless group discussion, in which their ability to interact with others is assessed by trained raters. Structured interviews and assessment centers are discussed in more detail later.

Employment Interviews

Employment interviews can be unstructured or structured (Huffcutt, Roth, & McDaniel, 1996). Schmidt and Hunter (1998) point out that the unstructured interviews have no fixed format or set of questions to be answered. There is no format for scoring responses. Structured interviews includes questions that are determined by a careful job analysis, and they have set questions and a set approach to scoring. Structured interviews have greater validity and show a 24% increase over cognitive ability alone in validity. Although there is no one universally accepted structured interview tool, depending on how structured the interview is, it might be based on detailed protocols so that candidates are asked the same questions and assessed against the same criteria. Interviewers are trained to ensure consistency between candidates (Judge, Higgins, & Cable, 2000).

As has been implied, the structured interview is a platform for assessment and can be designed to be used for developmental applicants. One if its functions can be to get at applicant or candidate interpersonal skills. For example, Landy (1976) found that interviews of prospective police officers were able to assess communication skills and personal stability. Arvey and Campion (1982) summarized evidence that the interview was suitable for determining sociability.

Assessment Centers

In assessment centers, the participant is observed participating in various exercises such as leaderless group discussions, supervisor/subordinate simulations, and business games. The average assessment center includes seven exercises and lasts two days (Gaugler, Rosenthal, Thornton, & Bentson, 1987). They have substantial validity but only moderate incremental validity over cognitive ability because they correlate highly with cognitive ability. Despite the lack of incremental validity, organizations use them because they provide a wealth of information useful for the individual’s development.

Interest Inventories

Such tools as Holland’s Vocational Preference Inventory (Holland et al., 1994) and Self-Directed Search (Holland, 1985), as well as the Strong Interest Inventory (Harmon, Hansen, Borgen, & Hammer, 1994) are used to help individuals going through a career change. Interest inventories are validated often against their ability to predict occupational membership criteria and satisfaction with a job (R. T. Hogan & Blake, 1996). There is evidence that interest inventories do predict occupational membership criteria (e.g., Cairo, 1982; Hansen, 1986). However, results are mixed with regard to whether there is a significant relationship between interests and job satisfaction (e.g., Cairo, 1982; Worthington & Dolliver, 1977). These results may exist because job satisfaction is affected by many factors, such as pay, security, and supervision. Additionally, there are individual differences in the expression of interests with a job. Regardless of their ability to predict these criteria, interest inventories have been useful to help individuals determine next steps in their career development.

Training and Experience Inventories

Schneider and Schneider (1994) point out that there are two assumptions of experience and training rating techniques. First, they are based on the notion that a person’s past behaviors are a valid predictor of what the person is likely to do in the future. Second, as individuals gain more experience in an occupation, they are more committed to it and will be more likely to perform well in it. There are various approaches to conducting these ratings. As an example, one approach is the point method, in which the raters provide points to candidates based on the type and length of a particular experience. Various kinds of experience and training would be differentially rated depending on the results of the job analysis. The literature on empirical validation of point method approaches suggests that they have sufficient validity. For example, McDaniel, Schmidt, and Hunter’s (1988) metaanalysis found a corrected validity coefficient of .15 for point method–based experience and training ratings. Questionnaires on biographical data contain questions about life experiences such as involvement in student organizations, offices held, and the like. This practice is based on the behavioral consistency theory, which suggests that past performance is the best predictor of future performance. Items are chosen because they have been shown to predict some criteria of job performance. Historical data, such as attendance and accomplishments, are included in these inventories. Research indicates that biodata measures correlate substantially with cognitive ability and that they have little or no incremental validity over it. Some psychologists even suggest that perhaps they are indirect measures of cognitive ability. These tools are often developed in-house based on the constructs deemed important for the job. Although there are some biodata inventories that are available for general use, most organizations develop tools suitable to their specific needs. For those interested, an example tool discussed as a predictor of occupational attainment (Snell, Stokes, Sands, & McBride, 1994) is the Owens Biographical Questionnaire (Owens & Schoenfeldt, 1979).

Measures of Job Performance

Measures of job performance are often in the form of supervisory ratings or multisource assessment platforms and can be used for promotions, salary increases, reductions in force, development, and for research purposes. Supervisory assessments, in the form of ratings, are the most prevalent assessments of job performance in industrial settings. The content is frequently standardized within an organization with regard to the job category and level. There may also be industry standards (e.g., for police officers or insurance auditors); however, specific ratings suitable for the context are also frequently used. Supervisors generally rate individuals on their personal traits and attributes related to the job, the processes by which they get the job done, and the products that result from their work. Multisource assessment platforms are based on evaluations gathered about a target participant from two or more rating sources, including self, supervisors, peers, direct reports, internal customers, external customers, and vendors or suppliers. The ratings are based on KSAOs related to the job. Results of multisource assessments can be either provided purely for development (as with Personnel Decision International Corporation’s Profiler, 1991) or shared with the supervisor as input to a personnel decision (Dalessio, 1998). The problem with the latter is that often the quality of ratings is poorer when the raters know that their evaluations will be used for personnel decisions (e.g., Murphy & Cleveland, 1995).

Major Issues

By virtue of our treatment of the material covered so far in this research paper, it should be clear that the scope of individual assessment activities in work contexts is quite great. Similarly, the number of individuals and the range of professions involved in this activity are diverse. It follows, then, that what constitutes an important issue or a problem is likely to be tied to stakeholder needs and perspective. In deference to this, we will briefly examine in this section issues that can be clustered around major stakeholder concerns related to business necessity, social policy, or technical or professional matters.