View sample Geography of Service Economy Research Paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of research paper topics for more inspiration. iResearchNet offers academic assignment help for students all over the world: writing from scratch, editing, proofreading, problem solving, from essays to dissertations, from humanities to STEM. We offer full confidentiality, safe payment, originality, and money-back guarantee. Secure your academic success with our risk-free services.

Producer services are types of services demanded primarily by businesses and governments, used as inputs in the process of production. We may split the demand for all services broadly into two categories: (a) demands originating from household consumers for services that they use, and (b) demands for services originating from other sources. An example of services demanded by household consumers is retail grocery services, while examples of producer services are management consulting services, advertizing services, and computer systems engineering.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

1. Development Of The Term ‘Producer Services’

Producer Services have emerged as one of the most rapidly growing industries in advanced economies, while the larger service economy has also exhibited aggregate growth in most countries. In the 1930s, Fisher (1939) observed the general tendency for shifts in the composition of employment as welfare rose, with an expanding service sector. Empirical evidence of this transformation was provided by Clark (1957), and the Clark–Fisher model was a popular description of development sequences observed in nations that were early participants in the Industrial Revolution. However, this model was criticized as a necessary pattern of economic development by scholars who observed regions and nations that did not experience the pattern of structural transformation encompassed in the Clark–Fisher model. Moreover, critics of the Clark–Fisher model also argued that the size of the service economy relative to that of goods and primary production required efforts to classify the service economy into categories more meaningful than Fisher’s residual category ‘services.’

The classification of service industries based upon their nature and their source of demand was pioneered in the 1960s and 1970s. The classic vision of services developed by Adam Smith (‘they perish the very instant of their performance’) was challenged as scholars recognized that services such as legal briefs or management services can have enduring value, similar to investments in physical capital. The term producer services became applied to services with ‘intermediate’ as opposed to ‘final’ markets.

While this distinction between intermediate or producer services and final or consumer services is appealing, it is not without difficulties. Some industries do not fit neatly into one category or another. For example, households as well as businesses and governments demand legal services, and hotels—a function generally regarded to a consumer service—serve both business travelers and households. Moreover, many of the functions performed by producer service businesses are also performed internally by other businesses. An example is the presence of in-house accounting functions in most businesses, while at the same time there are firms specializing in performing accounting services for their clients. Notwithstanding these difficulties of classification, there is now widespread acceptance of the producer services as a distinctive category of service industry. However, variations in the classification of industries among nations, as well as differences in the inclusion of specific industries by particular scholars leads to varying sectoral definitions of producer services. Business, legal, and engineering and management services are included in most studies, while the financial services are often considered to be a part of the producer services. It is less common to consider services to transportation, wholesaling, and membership organizations as a component of the producer services.

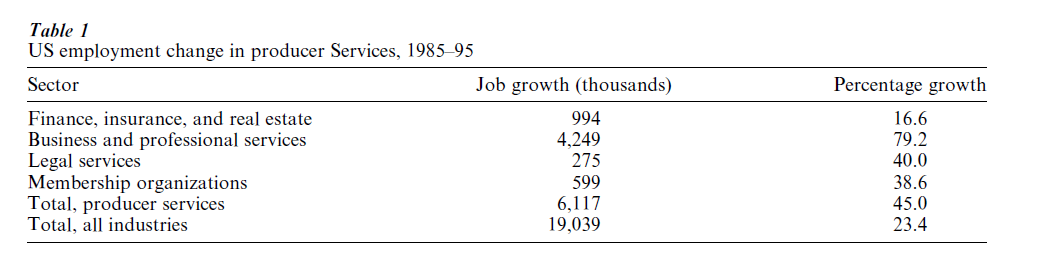

Table 1 documents for the US economy growth in producer services employment between 1985 and 1995 by broad industrial groups. The growth of producer services over this time period was double the national rate of job growth, and this growth rate was almost identical in metropolitan and rural areas. While financial services grew relatively slowly, employment growth in business and professional services was very strong. Key sectors within this group include temporary help agencies, advertizing, copy and duplicating, equipment rental, computer services, detective and protective, architectural and engineering, accounting, research and development, and management consulting and public relations services.

2. Early Research On The Geography Of Producer Services

Geographer’s and regional economist’s research on producer services only started in the 1970s. Pioneering research includes the investigations of office location in the United Kingdom by Daniels (1975), and the studies of corporate control, headquarters, and research functions related to corporate headquarters undertaken in the United States by Stanback (1979). Daniels (1985) provided a comprehensive summary of this research, distinguishing between theoretical approaches designed to explain the geography of consumer and producer services. The emphasis in this early research focused on large metropolitan areas, recognizing the disproportionate concentration of producer services employment in the largest nodal centers. This concentration was viewed as a byproduct of the search for agglomeration economies, both within freestanding producer services and in the research and development organizations associated with corporate headquarters. This early research also identified the growth of international business service organizations that were concentrated in large metropolitan areas to serve both transnational offices of home-country clients and to generate an international client base.

Early research on producer services also documented tendencies for decentralization from central business districts into suburban locations, as well as the relatively rapid development of producer services in smaller urban regions. In the United States, Noyelle and Stanback (1983) published the first comprehensive geographical portrait of employment patterns within the producer services, differentiating their structure through a classification of employment, and relating this classification to growth trends between 1959 and 1976. While documenting relatively rapid growth of producer services in smaller urban areas with relatively low employment concentrations, this early research did not point towards employment decentralization, although uncertainties related to the impact of the development of information technologies were recognized as a factor that would temper future geographical trends.

The geography of producer services was examined thoroughly in the United Kingdom through the use of secondary data in the mid-1980s (Marshall et al. 1988). This research documented the growing importance of the producer services as a source of employment, in an economy that was shedding manufacturing jobs. It encouraged a richer appreciation of the role of producer services by policy-makers and scholars and called for primary research to better understand development forces within producer service enterprises.

While many scholars in this early period of research on producer services emphasized market linkages with manufacturers or corporate headquarter establishments, other research found industrial markets to be tied broadly to all sectors of the economy, a fact also borne out in input-output accounts. Research also documented geographic markets of producer service establishments, finding that a substantial percentage of revenues were derived from nonlocal clients, making the producer services a component of the regional economic base (Beyers and Alvine 1985).

3. Emphasis In Current Research On The Geography Of Producer Services

In the 1990s there has been an explosion of geographic research on producer services. Approaches to research in recent years can be grouped into studies based on secondary data describing regional patterns or changes in patterns of producer service activity, and studies utilizing primary data to develop empirical insights into important theoretical issues. For treatment of related topics see Location Theory; Economic Geography; Industrial Geography; Finance, Geography of; Retail Trade; Urban Geography; and Cities: Capital, Global, and World.

3.1 Regional Distribution Of Producer Services

The uneven distribution of producer service employment continues to be documented in various national studies, including recent work for the United States, Canada, Germany, and the Nordic countries. While these regions have exhibited varying geographic trends in the development of producer services, they share in common the relatively rapid growth of these industries. They also share in common the fact that relatively few regions have a concentration of or a share of employment at or above the national average.

In Canada, the trend has been towards greater concentration, a pattern which Coffey and Shearmur (1996) describe as uneven spatial development. Utilizing data for the 1971 to 1991 time period, they find a broad tendency for producer service employment to have become more concentrated over time.

The trend in the United States, Germany, and the Nordic countries differs from that found in Canada. In the Nordic countries producer service employment is strongly concentrated in the capitals, but growth in peripheral areas of Norway and Finland is generally well above average, while in Denmark and Sweden many peripheral areas exhibit slow growth rates (Illeris and Sjøholt 1995). In Germany, the growth pattern exhibits no correlation between city size and the growth of business service employment (Illeris 1996). The United States also exhibits the uneven distribution of employment in the producer services. In 1995 only 34 of the 172 urban-focused economic areas defined by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis hAdvan employment concentration in producer services at or above the national average, and these were predominately the largest metropolitan areas in the country. However, between 1985 and 1995 the concentration of employment in these regions diminished somewhat, while regions with the lowest concentrations in 1985 tended to show increases in their level of producer services employment. Producer service growth rates in metropolitan and rural territory have been almost identical over this same time period in the United States. There is also considerable evidence of deconcentration of employment within metropolitan areas from central business districts into ‘Edge Cities’ and suburban locations in Canada and the United States (Coffey et al. 1996a, Coffey et al. 1996b, Harrington and Campbell 1997). Survey research in Montreal indicates that this deconcentration is related more strongly to new producer service businesses starting up in suburban locations than to the relocation of existing establishments from central city locations (Coffey et al. 1996b).

3.2 Producer Services And Regional Development

Numerous studies have now been undertaken documenting the geographic markets of producer service establishments; for summaries see Illeris (1996) and Harrington et al. (1991). Illeris’ summary of these studies indicates typical nonlocal market shares at 35 percent, but if nonlocal sales are calculated by weighting the value of sales the nonlocal share rises to 56 percent. In both urban and rural settings establishments are divided into those with strong interregional or international markets, and those with primarily localized markets. Over time establishments tend to become more export oriented, with American firms tending to have expanded interregional business, while European firms more often enter international markets (O’Farrell et al. 1998). Thus, producer services contribute to the economic base of communities and their contribution is rising over time due to their relatively rapid growth rate.

Growth in producer service employment in the United States has occurred largely through the expansion in the number of business establishments, with little change in the average size of establishments. Between 1983 and 1993 the number of producer service establishments increased from 0.95 million to 1.34 million, while average employment per establishment increased from 11 to 12 persons. The majority of this employment growth occurred in single unit establishments, nonpayroll proprietorships, and partnerships. People are starting these new producer service establishments because they want to be their own boss, they have identified a market opportunity, their personal circumstances lead them to wish to start a business, and they have identified ways to increase their personal income. Most people starting new companies were engaged in the same occupation in the same industry before starting their firm, and few report that they started companies because they were put out of work by their former employer in a move designed to downsize in-house producer service departments (Beyers and Lindahl 1996a).

The use of producer services also has regional development impacts. Work in New York State (MacPherson 1997) has documented that manufacturers who make strong use of producer services as inputs are more innovative than firms who do not use these services, which in turn has helped stimulate their growth rate. Similar positive impacts on the development of clients of producer service businesses has been documented in the United Kingdom (Wood 1996) and more broadly in Europe (Illeris 1996).

3.3 Demand Factors

Considerable debate has raged over the reasons for the rapid growth of the producer services, and one common perception has been that this growth has occurred because of downsizing and outsourcing by producer service clients to save money on the acquisition of these services. However, evidence has accumulated that discounts the significance of this perspective. Demand for producer services is increasing for a number of reasons beyond the cost of acquiring these services, based on research with both the users of these services and their suppliers (Beyers and Lindahl 1996a, Coffey and Drolet 1996). Key factors driving the demand for producer services include: the lack of expertise internal to the client to produce the service, a mismatch between the size of the client and the volume of their need for the service, the need for third-party opinions or expert testimony, increases in government regulations requiring use of particular services, and the need for assistance in managing the complexity of firms or to stay abreast of new technologies.

Evidence also indicates that producer service establishments often do business with clients who have in-house departments producing similar services. However, it is rare that there is direct competition with these in-house departments. Instead, relationships are generally complementary. Current evidence indicates that there have been some changes in the degree of inhouse vs. market acquisition of producer services, but those selling these services do not perceive the balance of these in-house or market purchases changing dramatically (Beyers and Lindahl 1996a).

3.4 Supply And Competitive Advantage Considerations

The supply of producer services is undertaken in a market environment that ranges from being highly competitive to one in which there is very little competition. In order to position themselves in this marketplace, producer service businesses exhibit competitive strategies, and as with the demand side, recent evidence points towards the prevalence of competitive strategies based on differentiation as opposed to cost (Lindahl and Beyers 1999, Hitchens et al. 1996, Coffey 1996). The typical firm tries to develop a marketplace niche, positioning itself to be different from competitors though forces such as an established reputation for supplying their specialized service, the quality of their service, their personal attention to client needs, their specialized expertise, the speed with which they can perform the service, their creativity, and their ability to adapt quickly to client needs. The ability to deliver the service at a lower cost than the client could produce it is also a factor considered important by some producer service establishments.

3.5 Flexible Production Systems

The flexible production paradigm has been extended from its origin in the manufacturing environment in recent years into the producer services (Coffey and Bailly 1991). There are a variety of aspects to the issue of flexibility in the production process, including the nature of the service being produced, the way in which firms organize themselves to produce their services, and their relationships with other firms in the production and delivery process. The labor force within producer services has become somewhat more complex, with the strong growth of the temporary help industry that dispatches a mixture of part-time and full-time temporary workers, as well as some increase in the use of contract or part-time employees within producer service establishments. However, over 90 percent of employment remains full-time within the producer services (Beyers and Lindahl 1999).

The production of producer services is most frequently undertaken in a manner that requires the labor force to be organized in a customized manner for each job, although a minority of firm’s approach work in a routinized manner. Almost three-fourths of firms rely on outside expertise to produce their service, and half of producer service firms engage in collaboration with other firms to produce their services to extend their range of expertise or geographic markets. The services supplied by producer service establishments are also changing frequently; half of the establishments interviewed in an US study had changed their services over the previous five years. They do so for multiple reasons, including changing client expectations, shifts in geographic or sectoral markets, changes in government regulations, and changes in information technologies with their related changes on the skills of employees. These changes most frequently produce more diversified service offerings, but an alternative pathway is to become more specialized or to change the form or nature of services currently being produced (Beyers and Lindahl 1999).

3.6 Information Technologies

Work in the producer services typically involves face to face meetings with clients at some point in the production process. This work may or may not require written or graphical documents. In some cases the client must travel to the producer service firm’s office, and in other cases the producer service staff travels to client. These movements can be localized or international in scale. However, in addition to these personal meetings, there is extensive and growing use of a variety of information technologies in the production and delivery of producer services work. Computer networks, facsimile machines, telephone conversations, courier services, and the postal system all play a role, including a growing use of the Internet, e-mail, and computer file transfers between producers and clients. Some routine functions have become the subject of e-commerce, but much of the work undertaken in the producer services is nonroutine, requiring creative interactions between clients and suppliers.

3.7 Location Factors

The diversity of market orientations of producer service establishments leads to divergent responses with regard to the choice of business locations (Illeris 1996). Most small establishments are located convenient to the residential location of the founder. However, founders often search for a residence that suits them, a factor driven by quality of life considerations for many rural producer service establishments (Beyers and Lindahl 1996b). Businesses with spatially dispersed markets are drawn to locations convenient to travel networks, including airports and the Interstate Highway System in the US. Businesses with highly localized markets position themselves conveniently to these markets. Often ownership of a building, or a prestigious site that may affect trust or confidence of clients is an influencing factor. Establishments that are part of large multi-establishment firms select locations useful from a firm-network-of-locations perspective, which may be either an intra-or interurban pattern of offices.

4. Methodological Considerations

Much of the research reported upon here has been conducted in the United States, Canada, or the United Kingdom. While there has been a rapid increase in the volume of research reported regarding the themes touched upon in the preceding paragraphs, the base of field research is still slender even within the nations just mentioned. More case studies are needed in urban and rural settings, focused on marketplace dynamics, production processes, and the impact of technological development on the evolution of the producer services. The current explosion of e-commerce and its use by producer service firms is a case in point. Recent research has tended to be conducted either by surveying producer service enterprises or their clients, but only rarely are both surveyed to obtain answers that can be cross-tabulated. Individual researchers have developed their protocol for survey research, yielding results that tend to be noncomparable to other research. Means need to be developed to bring theoretical and empirical approaches into greater consistency and comparability.

There are variations in the organization of production systems related to the producer services among countries. Some countries internalize these functions to a relatively high degree within other categories of industrial activity, and there needs to be greater thought given to ways in which research on these functions within these organizations can be measured.

5. Future Directions Of Theory And Research

Research on the producer services will continue at both an aggregate scale, as well as at the level of the firm or establishment. Given the recent history of job growth in this sector of advanced economies, there will certainly be studies documenting the ongoing evolution of the geographical distribution of producer services. This research needs to proceed at a variety of spatial scales, ranging from intrametropolitan, to intermetropolitan or interregionally within nations, and across nations. International knowledge of development trends is currently sketchy, especially in developing countries where accounts may be less disaggregate than in developed countries with regard to service industries.

Research at the level of the firm and establishment must continue to better understand the start-up and evolution of firms. While there is a growing body of evidence regarding motivations and histories of firm founders, there is currently little knowledge of the movement of employees into and among producer service establishments. There is also meager knowledge of the distribution of producer service occupations and work in establishments not classified as producer services. Case studies are needed of collaboration, subcontracting, client-seller interaction, processes of price formation, the interplay between the evolution of information technologies and serviceproduct concepts, and types of behavior that are related to superior performance as measured by indicators such as sales growth rate, sales per employee, or profit. There is also a pressing need for international comparative research, not just in the regions that have been relatively well researched (generally the US, Canada, and Europe), but also in other parts of the planet. There is also a pressing need for the development of more robust models and theory in relation to the geography of producer services.

Bibliography:

- Beyers W B, Alvine M J 1985 Export services in postindustrial society. Papers of the Regional Science Association 57: 33–45

- Beyers W B, Lindahl D P 1996a Explaining the demand for producer services: Is cost-driven externalization the major factor? Papers in Regional Science 75: 351–74

- Beyers W B, Lindahl D P 1996b Lone eagles and high fliers in rural producer services. Rural Development Perspectives 12: 2–10

- Beyers W B, Lindahl D P 1999 Workplace flexibilities in the producer services. The Service Industries Journal 19: 35–60

- Clark C 1957 The Conditions of Economic Progress. Macmillan, London

- Coffey W J 1996 Forward and backward linkages of producer service establishments: Evidence from the Montreal metropolitan area. Urban Geography 17: 604–32

- Coffey W J, Bailly A S 1991 Producer services and flexible production: An exploratory analysis. Growth and Change 22: 95–117

- Coffey W J, Drolet R 1996 Make or buy? Internalization and externalization of producer service inputs in the Montreal metropolitan area. Canadian Journal of Regional Science 29: 25–48

- Coffey W J, Drolet R, Polese M 1996a The intrametropolitan location of high order services: Patterns, factors and mobility in Montreal. Papers in Regional Science 75: 293–323

- Coffey W J, Polese M, Drolet R 1996b Examining the thesis of central business district decline: Evidence from the Montreal metropolitan area. Environment and Planning A 28: 1795–1814

- Coffey W J, Shearmur R G 1996 Employment Growth and Change in the Canadian Urban System, 1971–94. Canadian Policy Research Networks, Ottawa, Canada

- Daniels P W 1975 Office Location. Bell, London

- Daniels P W 1985 Service Industries, A Geographical Appraisal. Methuen, London

- Fisher A 1939 Production, primary, secondary, and tertiary. Economic Record 15: 24–38

- Harrington J W, Campbell H S Jr 1997 The Suburbanization of Producer Service Employment. Growth and Change 28: 335–59

- Harrington J W, MacPherson A D, Lombard J R 1991 Interregional trade in producer services: Review and synthesis. Growth and Change 22: 75–94

- Hitchens D M W N, O’Farrell P N, Conway C D 1996 The competitiveness of business services in the Republic of Northern Ireland, Wales, and the south East of England. Environment and Planning A 28: 1299–1313

- Illeris S 1996 The Service Economy. A Geographical Approach. Wiley, Chichester, UK

- Illeris S, Sjøholt P 1995 The Nordic countries: High quality services in a low density environment. Progress Planning 43: 205–221

- Lindahl D P, Beyers W B 1999 The creation of competitive advantage by producer service establishments. Economic Geography 75: 1–20

- MacPherson A 1997 The role of producer service outsourcing in the innovation performance of New York State manufacturing firms. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 87: 52–71

- Marshall J, Wood P A, Daniels P W, McKinnon A, Bachtler J, Damesick P, Thrift N, Gillespie A, Green A, Leyshon A 1988 Services and Uneven Development. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK

- Noyelle T J, Stanback T M 1983 The Economic Transformation of American Cities. Rowman and Allanheld, Totowa, NJ

- O’Farrell P N, Wood P A, Zheng J 1998 Regional influences on foreign market development by business service companies: Elements of a strategic context explanation. Regional Studies 32: 31–48

- Stanback T M 1979 Understanding the Service Economy: Employment, Productivity, Location. Allanheld and Osmun, Totowa, NJ

- Wood P 1996 Business services, the management of change and regional development in the UK: A corporate client perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21: 649–65