View sample ethical issues in psychological assessment research paper. Browse other research paper examples and check the list of psychology research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our custom writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Psychological assessment is unique among the services provided by professional psychologists. Unlike psychotherapy, in which clients may come seeking help for themselves, psychological evaluation services are seldom performed solely at the request of a single individual. In the most common circumstances, people are referred to psychologists for assessment by third parties with questions about school performance, suitability for potential employment, disability status, competence to stand trial, or differential clinical diagnosis.The referring parties are invariably seeking answers to questions with varying degrees of specificity, and these answers may or may not be scientifically addressable via the analysis of psychometric data. In addition, the people being tested may benefit (e.g., obtain remedial help, collect damages, or gain a job offer) or suffer (e.g., lose disability benefits, lose custody of a child, or face imprisonment) as a consequence of the assessment, no matter how competently it is carried out.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Psychological assessment is founded on a scientific base and has the capacity to translate human behavior, characteristics, and abilities into numbers or other forms that lend themselves to description and comparison across individuals and groups of people. Many of the behaviors studied in the course of an evaluation appear to be easily comprehensible to the lay person unfamiliar with test development and psychometrics (e.g., trace a path through a maze, perform mental arithmetic, repeat digits, or copy geometric shapes)—thereby implying that the observed responses must have some inherent validity for some purpose. Even common psychological assessment tasks that may be novel to most people (e.g., Put this unusual puzzle together quickly. What does this inkblot look like to you?) are imbued by the general public with some implied valuable meaning.After all, some authority suggested that the evaluation be done, and the person conducting the evaluation is a licensed expert. Unfortunately, the statistical and scientific underpinnings of the best psychological assessments are far more sophisticated than most laypersons and more than a few psychologists understand them to be. When confronted with an array of numbers or a computer-generated test profile, some people are willing to uncritically accept these data as simple answers to incredibly complex questions. This is the heart of the ethical challenge in psychological assessment: the appropriate use of psychological science to make decisions with full recognition of its limitations and the legal and human rights of the people whose lives are influenced.

In attempting to address the myriad issues that challenge psychologists undertaking to conduct assessments in the most ethically appropriate manner, it is helpful to think in terms of the prepositions before, during, and after. There are ethical considerations best addressed before the assessment is begun, others come into play as the data are collected and analyzed, and still other ethical issues crop up after the actual assessment is completed. This research paper is organized to explore the ethical problems inherent in psychological assessment using that same sequence.

In the beginning—prior to meeting the client and initiating data collection—it is important to consider several questions. What is being asked for and by whom (i.e., who is the client and what use does that person hope to make of the data)? Is the proposed evaluator qualified to conduct the evaluation and interpret the data obtained? What planning is necessary to assure the adequacy of the assessment? What instruments are available and most appropriate for use in this situation?

As one proceeds to the actual evaluation and prepares to undertake data collection, other ethical issues come to the fore. Has the client (or his or her representative) been given adequate informed consent about both the nature and intended uses of the evaluation? Is it clear who will pay for the evaluation, what is included, and who will have access to the raw data and report? What are the obligations of the psychologist with respect to optimizing the participants’ performance and assuring validity and thoroughness in documentation? When the data collection is over, what are the examiner’s obligations with respect to scoring, interpreting, reporting, and explaining the data collected?

Finally, after the data are collected and interpreted, what are the ongoing ethical responsibilities of the psychologist with respect to maintenance of records, allowing access to the data, and providing feedback or follow-up services? What is appropriate conduct when one psychologist is asked to review and critique another psychologist’s work? How should one respond upon discovery of apparent errors or incompetence of a colleague in the conduct of a now-completed evaluation?

This research paper was completed during a period of flux in the evolution of theAmerican PsychologicalAssociation’s (APA) Ethical Standards of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. The current, in-force version of this document was adopted in 1992 (APA, 1992), but work on a revision is nearing completion (Ethics CodeTask Force, 2001); a vote on adoption of the newest revision should take place in 2002. Many of the proposed revisions deal with psychological assessment. The Ethics Code Task Force (ECTF) charged with revising the code set out to avoid fixing that which is not broken—that is, the proposed changes focused on problems raised in a critical incident survey of psychologists, intended to ascertain where clarification and change were needed to improve professional and scientific practices. We have chosen to focus this research paper on key ethical foundations, but we also identify areas of controversy throughout. Whenever possible, we discuss trends and likely policy decisions based on the work of the ECTF; however, readers are encouraged to visit the APA Web site (http://www.apa.org/ethics) to view the most current version of the code and standards, which will continue to evolve long after this research paper appears in print.

In the Beginning

Who Is the Client?

The first step in undertaking the evaluator role is often seductively automatic. The simple act of accepting the referral and setting up the appointment may occur almost automatically; not much thought may be devoted to the question of what specific duties or professional obligations are owed to which parties. Is the client simply the person to be evaluated, or are there layers of individuals and institutions to whom the psychologist owes some degree of professional obligation? For example, is the person to be evaluated a legally competent adult? If not—as in the case of children or dependent adults— the party seeking the evaluation may be a parent, guardian, government agency, institution, or other legally responsible authority. The evaluator must pause to consider what rights each layer of authority has in terms of such factors as the ability to compel cooperation of the person to be assessed, the right of access to test data and results, and the right to dictate components of the evaluation or the manner in which it is conducted. Sometimes there is uniform agreement by all parties, and no conflicts of interest take place. In other circumstances, the person being evaluated may have had little choice in the matter or may wish to reserve the right to limit access to results of the evaluation. In still other instances, there may be direct conflicts between what one party is seeking and the objectives of another party with some degree of client status.

Evaluations conducted in the context of the educational system provide a good example of the complex layers of client status that can be involved. Suppose that a schoolchild is failing and an assessment is requested by the child’s family for use in preparation of an individualized educational plan (IEP) as specified under state or federal special education laws. If a psychologist employed by the public school system undertakes the task, that evaluator certainly owes a set of professional duties (e.g., competence, fairness, etc.) to the child, to the adults acting on behalf of the child (i.e., parents or guardians), to the employing school system, and—by extension—to the citizens of the community who pay school taxes. In the best of circumstances, there may be no problem—that is to say, the evaluation will identify the child’s needs, parents and school will agree, and an appropriate effective remediation or treatment component for the IEP will be put in place.

The greater ethical challenge occurs when parents and school authorities disagree and apply pressure to the evaluator to interpret the data in ways that support their conflicting demands. One set of pressures may apply when the psychologist is employed by the school, and another may apply when the evaluation is funded by the parents or another third party. From an ethical perspective, there should be no difference in the psychologist’s behavior. The psychologist should offer the most scientifically and clinically sound recommendations drawn from the best data while relying on competence and personal integrity without undue influence from external forces.

Similar conflicts in competing interests occur frequently within the legal system and the business world—a person may agree to psychological assessment with a set of hopes or goals that may be at variance or in direct conflict with the data or the outcomes desired by another party in the chain of people or institutions to whom the evaluator may owe a professional duty. Consider defendants whose counsel hope that testing will support insanity defenses, plaintiffs who hope that claims for psychological damages or disability will be supported, or job applicants who hope that test scores will prove that they are the best qualified. In all such instances, it is critical that the psychologist conducting the assessment strive for the highest level of personal integrity while clarifying the assessment role and its implications to all parties to whom a professional duty is owed.

Other third parties (e.g., potential employers, the courts, and health insurers) are involved in many psychological assessment contexts. In some cases, when the psychologist is an independent practitioner, the third party’s interest is in making use of the assessment in some sort of decision (e.g., hiring or school placement); in other cases, the interest may simply be contract fulfillment (e.g., an insurance company may require that a written report be prepared as a condition of the assessment procedure). In still other situations, the psychologist conducting the evaluation may be a full-time employee of a company or agency with a financial interest in the outcome of the evaluation (e.g., an employer hoping to avoid a disability claim or a school system that wishes to avoid expensive special education placements or services). For all these reasons, it is critical that psychologists clearly conceptualize and accurately represent their obligations to all parties.

Informed Consent

The current revision of the ECTF (2001) has added a proposed standard referring specifically to obtaining informed consent for psychological assessment. The issue of consent is also discussed extensively in the professional literature in areas of consent to treatment (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998) and consent for research participation, but Bibliography: to consent in the area of psychological assessment had been quite limited. Johnson-Greene, Hardy-Morais, Adams, Hardy, and Bergloff (1997) review this issue and propose a set of recommendations for providing informed consent to clients. These authors also propose that written documentation of informed consent be obtained; the APA ethical principles allow but do not require this step. We believe that psychologists would be wise to establish consistent routines and document all discussions with clients related to obtaining consent, explaining procedures, and describing confidentiality and privacy issues. It is particularly wise to obtain written informed consent in situations that may have forensic implications, such as personal injury lawsuits and child custody litigation.

Psychologists are expected to explain the nature of the evaluation, clarify the referral questions, and discuss the goals of the assessment, in language the client can readily understand. It is also important to be aware of the limitations of the assessment procedures and discuss these procedures with the client. To the extent possible, the psychologist also should be mindful of the goals of the client, clarify misunderstandings, and correct unrealistic expectations. For example, parents may seek a psychological evaluation with the expectation that the results will ensure that their child will be eligible for a gifted and talented program, accident victims may anticipate that the evaluation will document their entitlement to damages, and job candidates may hope to become employed or qualify for advancement. These hopes and expectations may come to pass, but one cannot reasonably comment on the outcome before valid data are in hand.

Whether the assessment takes place in a clinical, employment, school, or forensic settings, some universal principles apply. The nature of assessment must be described to all parties involved before the evaluation is performed. This includes explaining the purpose of the evaluation, who will have access to the data or findings, who is responsible for payment, and what any relevant limitations are on the psychologist’s duties to the parties. In employment contexts, for example, the psychologist is usually hired by a company and may not be authorized to provide feedback to the employee or candidate being assessed. Similarly, in some forensic contexts, the results of the evaluation may ultimately be open to the court or other litigants over the objections of the person being assessed. In each case, it is the psychologist’s responsibility to recognize the various levels of people and organizations to whom a professional duty may be owed and to clarify the relationship with all parties at the outset of the assessment activity.

The key elements of consent are information, understanding, and voluntariness. First, do the people to be evaluated have all the information that might reasonably influence their willingness to participate? Such information includes the purpose of the evaluation, who will have access to the results, and any costs or charges to them. Second, is the information presented in a manner that is comprehensible to the client? This includes use of appropriate language, vocabulary, and explanation of any terms that are confusing to the client. Finally, is the client willing to be evaluated? There are often circumstances in which an element of coercion may be present. For example, the potential employee, admissions candidate, criminal defendant, or person seeking disability insurance coverage might prefer to avoid mandated testing. Such prospective assessment clients might reluctantly agree to testing in such a context because they have no other choice if they wish to be hired, gain admission, be found not criminally responsible, or adjudicated disabled, respectively. Conducting such externally mandated evaluations do not pose ethical problems as long as the nature of the evaluation and obligations of the psychologist are carefully delineated at the outset. It is not necessary that the person being evaluated be happy about the prospect—he or she must simply understand and agree to the assessment and associated risks, much like people referred for a colonoscopy or exploratory surgery.

Additional issues of consent and diminished competence come into play when a psychologist is called upon to evaluate a minor child, an individual with dementia, or other persons with reduced mental capacity as a result of significant physical or mental disorder.When such an evaluation is undertaken primarily for service to the client (e.g., as part of treatment planning), the risks to the client are usually minimal. However, if the data might be used in legal proceedings (e.g., a competency hearing) or in any way that might have significant potentially adverse future consequences that the client is unable to competently evaluate, a surrogate consent process should be used—that is to say, a parent or legal guardian ought to be involved in granting permission for the evaluation. Obtaining such permission helps to address and respect the vulnerabilities and attendant obligations owed to persons with reduced personal decision-making capacities.

Test User Competence

Before agreeing to undertake a particular evaluation, the clinician should be competent to provide the particular service to the client, but evaluating such competence varies with the eye of the beholder. Psychologists are ethically bound not to promote the use of psychological assessment techniques by unqualified persons, except when such use is conducted for training purposes with appropriate supervision. Ascertaining what constitutes competence or qualifications in the area of psychological assessment has been a difficult endeavor due to the complex nature of assessment, the diverse settings and contexts in which psychological assessments are performed, and the differences in background and training of individuals providing psychological assessment services. Is a doctoral degree in clinical, counseling, or school psychology required? How about testing conducted by licensed counselors or by individuals with master’s degrees in psychology? Are some physicians competent to use psychological tests? After all, Hermann Rorschach was a psychiatrist, and so was J. Charnley McKinley, one of the two originators of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI). Henry Murray, a nonpsychiatric physician, coinvented the thematic apperception test (TAT) with Christiana Morgan, who had no formal training in psychology.

Historically, the APA addressed this issue only in a very general manner in the Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct for Psychologists. In earliest versions of the Ethical Standards of Psychologists (APA, 1953), the ethical distribution and sale of psychological tests was to be limited to unspecified “qualified persons.” A system of categorization of tests and concordant qualifications that entailed three levels of tests and expertise was subsequently developed.Vocational guidance tools, for example, were at the low end in terms of presumed required expertise. At the high end of required competence were tests designed for clinical assessment and diagnoses such as intelligence and personality assessment instruments. The rationale involved in this scheme was based on the need to understand statistics, psychopathology, and psychometrics in order to accurately draw clinical inference or make actuarial predictions based on the test data.Although the three-tier system is no longer discussed in APA ethical standards, it was adopted by many test publishers, and variations continue in use. When attempting to place orders for psychological test materials, would-be purchasers are often asked to list their credentials, cite a professional license number, or give some other indication of presumed competence. Decisions about the actual sale are generally made by the person processing the order—often a clerk who has little understanding of the issues and considerable incentive to help the test publisher make the sale. Weaknesses and inconsistencies in the implementation of these criteria are discussed in a recent Canadian study (Simner, 1994).

Further efforts to delineate qualifications of test users included the lengthy efforts of the Test User Qualifications Working Group (TUQWG) sponsored by an interdisciplinary group, the Joint Committee on Testing Practices, which was convened and funded by the APA. To study competence problems, this group of professionals and academics attempted to quantify and describe factors associated with appropriate test use by using a data-gathering (as opposed to a specification of qualifications) approach (Eyde, Moreland, Robertson, Primoff, & Most, 1988; Eyde et al., 1993; Moreland, Eyde, Robertson, Primoff, & Most, 1995).

International concerns regarding competent test use— perhaps spurred by expansion of the European Economic Community and the globalization of industry—prompted the British Psychological Society (BPS) to establish a certification system that delineates specific competencies for the use of tests (BPS, 1995, 1996) in employment settings. Under this system, the user who demonstrates competence in test use is certified and listed in an official register. Professionals aspiring to provide psychological assessment services must demonstrate competence with specific tests to be listed. The International Test Commission (2000) recently adopted test-use guidelines describing the knowledge, competence, and skills.

Within the United States, identifying test user qualifications and establishing competence in test use have been complicated by political and practical issues, including the potential for nonprofit professional groups to be accused of violating antitrust laws, the complexity of addressing the myriad settings and contexts in which tests are used, and the diversity of experience and training in assessment among the professionals who administer and interpret psychological tests. Further complicating matters is the trend in recent years for many graduate programs in psychology to de-emphasize psychological assessment theory and practice in required course work, producing many licensed doctoral psychologists who are unfamiliar with contemporary measurement theory (Aiken, West, Sechrest, & Reno, 1990).

In October of 1996, theAPAformed a task force to develop more specific guidelines in the area of test user qualifications and competence (Task Force on Test User Qualifications). Members of the task force were selected to represent the various settings and areas of expertise in psychological assessment (clinical, industrial/organizational, school, counseling, educational, forensic, and neuropsychological). Instead of focusing on qualifications in terms of professional degrees or licenses, the task force elected to delineate a core set of competencies in psychological assessment and then describe more specifically the knowledge and skills expected of test users in specific contexts. The core competencies included not only knowledge of psychometric and measurement principles and appropriate test administration procedures but also appreciation of the factors affecting tests’ selection and interpretation in different contexts and across diverse individuals.

Other essential competencies listed by the task force included familiarity with relevant legal standards and regulations relevant to test use, including civil rights laws, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Public commentary in response to the Task Force’s preliminary report emphasized the variety of settings and purposes involved and generally argued against a focus on degrees and licenses as providing adequate assurance of competence. The Task Force delineated the purposes for which tests are typically used (e.g., classification, description, prediction, intervention planning, and tracking) and described the competencies and skills required in specific settings (e.g., employment, education, career-vocational counseling, health care, and forensic). The task force’s recommendations were drafted as aspirational guidelines describing the range of knowledge and skills for optimal test use in various contexts. The task force report also expressed the hope that the guidelines would serve to bolster the training of future psychologists in the area of assessment. The final report of the task force was approved by the APACouncil of Representatives in August 2000.

The chief ethical problems in this area involve matters of how to objectively determine one’s own competence and how to deal with the perceived lack of competence in others whose work is encountered in the course of professional practice. The key to the answer lies in peer consultation. Discussion with colleagues, teachers, and clinical supervisors is the best way to assess one’s emerging competence in assessment and focus on additional training needs. Following graduation and licensing, continuing professional education and peer consultation are the most effective strategies for assessing and maintaining one’s own competence. When in doubt, presenting samples of one’s work to a respected senior colleague for review and critique is a useful strategy. If one’s competence is ever challenged before a court, ethics committee, or licensing board, the expert testimony of senior colleagues will be used in an effort to prove incompetence or negligence. By consulting with such colleagues regularly, one can be continuously updated on any perceived problems with one’s own work and minimize the risk of criticism in this regard.

Dealing with the less-than-adequate work of others poses a different set of ethical concerns. At times psychologists may become aware of inadequate assessment work or misuse of psychological tests by colleagues or individuals from other professions (e.g., physicians or nonpsychologist counselors). Such individuals may be unaware of appropriate testing standards or may claim that they disagree with or are not bound by them. Similarly, some psychologists may attempt to use assessment tools they are not qualified to administer or interpret. The context in which such problems come to light is critical in determining the most appropriate course of action. The ideal circumstance is one in which the presumed malefactor is amenable to correcting the problem as a result of an informal conversation, assuming that you have the consent of the party who has consulted you to initiate such a dialogue. Ideally, a professional who is the recipient of an informal contact expressing concern about matters of assessment or test interpretation will be receptive to and interested in remedying the situation. When this is not the case, the client who has been improperly evaluated should be advised about potential remedies available through legal and regulatory channels.

If one is asked to consult as a potential expert witness in matters involving alleged assessment errors or inadequacies, one has no obligation to attempt informal consultation with the professional who rendered the report in question. In most cases, such contact would be ethically inappropriate because the client of the consulting expert is not the person who conducted the assessment. In such circumstances, the people seeking an expert opinion will most likely be attorneys intent on challenging or discrediting a report deemed adverse to their clients. The especially complex issues raised when there are questions of challenging a clinician’s competence in the area of neuropsychological assessment are effectively discussed by Grote, Lewin, Sweet, and van Gorp (2000).

Planning the Evaluation

As an essential part of accepting the referral, the psychologist should clarify the questions to be answered in an interactive process that refines the goals of the evaluation in the context of basic assessment science and the limitations of available techniques; this is especially important when the referral originates with nonpsychologists or others who may be unaware of the limitations of testing or may have unrealistic expectations regarding what they may learn from the test data.

Selection of Instruments

In attempting to clarify the ethical responsibilities of psychologists conducting assessments, the APA’s ECTF charged with revision of the code concluded that psychologists should base theirassessments,recommendations,reports,opinions,anddiagnostic or evaluative statements on information and techniques sufficient to substantiate their findings (ECTF, 2001). The psychologist should have a sound knowledge of the available instruments for assessing the particular construct related to the assessment questions. This knowledge should include an understanding of the psychometric properties of the instruments being employed (e.g., their validity, reliability, and normative base) as well as an appreciation of how the instrument can be applied in different contexts or with different individuals across age levels, cultures, languages, and other variables. It is also important for psychologists to differentiate between the instrument’s strengths and weaknesses such that the most appropriate and valid measure for the intended purpose is selected. For example, so-called floor and ceiling constraints can have special implications for certain age groups. As an illustration, the Stanford-Binet, Fourth Edition, has limited ability to discriminate among children with significant intellectual impairments at the youngest age levels (Flanagan & Alfonso, 1995). In evaluating such children, the use of other instruments with lower floor capabilities would be more appropriate.

Adequacy of Instruments

Consistent with both current and revised draft APA standards (APA, 1992; ECTF, 2001), psychologists are expected to develop, administer, score, interpret, or use assessment techniques, interviews, tests, or instruments only in a manner and for purposes that are appropriate in light of the research on or evidence of the usefulness and proper application of the techniques in question. Psychologists who develop and conduct research with tests and other assessment techniques are expected to use appropriate psychometric procedures and current scientific or professional knowledge in test design, standardization, validation, reduction or elimination of bias, and recommendations for use of the instruments. The ethical responsibility of justifying the appropriateness of the assessment is firmly on the psychologist who uses the particular instrument. Although a test publisher has some related obligations, the APA ethics code can only be enforced against individuals who are APAmembers, as opposed to corporations. The reputations of test publishers will invariably rise or fall based on the quality of the tools they develop and distribute. When preparing new assessment techniques for publication, the preparation of a test manual that includes the data necessary for psychologists to evaluate the appropriateness of the tool for their work is of critical importance. The psychologist in turn must have the clinical and scientific skill needed to evaluate the data provided by the publisher.

Appropriate Assessment in a Multicultural Society

In countries with a citizenry as diverse as that of the United States, psychologists are invariably confronted with the challenge of people who by reason of race, culture, language, or other factors are not well represented in the normative base of frequently used assessment tools. Such circumstances demand consideration of a multiplicity of issues. When working with diverse populations, psychologists are expected to use assessment instruments whose validity and reliability have been established for that particular population. When such instruments are not available, the psychologist is expected to take care to interpret test results cautiously and with regard to the potential bias and potential misuses of such results. When appropriate tests for a particular population have not been developed, psychologists who use existing standardized tests may ethically adapt the administration and interpretation procedures only if the adaptations have a sound basis in the scientific and experiential foundation of the discipline. Psychologists have an ethical responsibility to document any such adaptations and clarify their probable impact on the findings. Psychologists are expected to use assessment methods in a manner appropriate to an individual’s language preference, competence, and cultural background, unless the use of an alternative language is relevant to the purpose of the assessment.

Getting Around Language Barriers

Some psychologists incorrectly assume that the use of an interpreter will compensate for a lack of fluency in the language of the person being tested. Aside from the obvious nuances involved in vocabulary, the meaning of specific instructions can vary widely. For example, some interpreters may tend to simplify instructions or responses rather than give precise linguistic renditions. At other times, the relative rarity of the language may tempt an examiner to use family or community members when professional interpreters are not readily available. Such individuals may have personal motives that could lead to alterations in the meaning of what was actually said, or their presence may compromise the privacy of the person being assessed. Psychologists using the services of an interpreter must assure themselves of the adequacy of the interpreter’s training, obtain the informed consent of the client to use that particular interpreter, and ensure that the interpreter will respect the confidentiality of test results and test security. In addition, any limitations on the data obtained via the use of an interpreter must be discussed in presenting the results of the evaluation.

Some psychologists mistakenly assume that they can compensate for language or educational barriers by using measures that do not require verbal instructions or responses. When assessing individuals of diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, it is not sufficient to rely solely on nonverbal procedures and assume that resulting interpretations will be valid. Many human behaviors, ranging from the nature of eye contact; speed, spontaneity, and elaborateness of response; and persistence on challenging tasks may be linked to social or cultural factors independent of language or semantics. It has been demonstrated, for example, that performance on nonverbal tests can be significantly affected both by culture (Ardila & Moreno, 2001) and by educational level (Ostrosky, Ardila, Rosselli, Lopez-Arango, & Uriel-Mendoza, 1998).

What’s in a Norm?

Psychologists must have knowledge of the applicability of the instrument’s normative basis to the client. Are the norms up-todate and based on people who are compatible with the client? If the normative data do not apply to the client, the psychologist must be able to discuss the limitations in interpretation. In selecting tests for specific populations, it is important that the scores be corrected not only with respect to age but also with respect to educational level (Heaton, Grant, & Matthews, 1991; Vanderploeg, Axelrod, Sherer, Scott, & Adams, 1997). For example, the assessment of dementia in an individual with an eighth-grade education would demand very different considerations from those needed for a similar assessment in a person who has worked as a college professor.

Psychologists should select and interpret tests with an understanding of how specific tests and the procedures they entail interact with the specific individual undergoing evaluation. Several tests purporting to evaluate the same construct (e.g., general cognitive ability) put variable demands on the client and can place different levels of emphasis on specific abilities. For example, some tests used with young children have different expectations for the amoun to flanguage used in the instructions and required of the child in a response. Achild with a specific language impairment may demonstrate widely discrepant scores on different tests of intelligence as a function of the language load of the instrument because some tests can place a premium on verbal skills (Kamphaus, Dresden, & Kaufman, 1993).

It is important to remember that psychologists must not base their assessment, intervention decisions, or recommendations on outdated data or test results. Similarly, psychologists do not base such decisions or recommendations on test instruments and measures that are obsolete. Test kits can be expensive, and more than a few psychologists rationalize that there is no need to invest in a newly revised instrument when they already own a perfectly serviceable set of materials of the previous edition. In some instances, a psychologist may reasonably use an older version of a standardized instrument, but he or she must have an appropriate and valid rationale to justify the practice. For example, a psychologist may wish to assess whether there has been deterioration in a client’s condition and may elect to use the same measure as used in prior assessments such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales–Revised (WAIS-R), even if a newer improved version such as theWAIS-III is now available.

Bases for Assessment

The current APA ethics code holds that psychologists typically provide opinions on the psychological characteristics of individuals only after conducting an examination of the individuals that is adequate to support the psychologists’statements or conclusions. This provision is confusing in some contexts.At times such an examination is not practical (e.g., when a psychologist serving as an expert witness is asked to offer hypothetical opinions regarding data sets collected by others). Another example would occur when a psychologist is retained to provide confidential assistance to an attorney. Such help might be sought to explore the accuracy of another’s report or to help the attorney frame potential cross-examination questions to ask the other side’s expert. In such situations, psychologists document the efforts they made to obtain their own data (if any) and clarify the potential impact of their limited information on the reliability and validity of their opinions.

The key to ethical conduct in such instances is to take great care to appropriately limit the nature and extent of any conclusions or recommendations. Related areas of the current APA code include Standards 2.01 (Boundaries of Competence) and 9.06 (Interpreting Assessment Results). When psychologists conduct record review and an individual examination is not warranted or necessary for their opinions, psychologists explain this situation and the bases upon which they arrived at this opinion in their conclusions and recommendations. This same issue is addressed in the pending revision (ECTF, 2001) as part of a new section—Section 9 (Assessment). Subsection c of 9.01 (Bases forAssessments) indicates that when despite reasonable efforts, examination of an individual is impractical, “psychologists document theefforts theymade and the result of those efforts, clarify the probable impact of their limited information on the reliability and validity of their opinions, and appropriately limit the nature and extent of their conclusions or recommendations” (ECTF, 2001, p. 18).

Subsection d addresses the issue of record review. This practice is especially common in the forensic arena; attorneys often want their own expert to examine the complete data set and may not wish to disclose the identity of the expert to the other side. When psychologists conduct record reviews and when “an individual examination is not warranted or necessary for the opinion, psychologists explain this and the bases upon which they arrived at this opinion in their conclusions and recommendations” (ECTF, 2001, p. 18).

This circumstance of being able to ethically offer an opinion with limitations—absent a direct assessment of the client—is also germane with respect to requests for the release of raw test data, as discussed later in this research paper.

Conducting the Evaluation

The requirements for and components of informed consent— including contracting details (i.e., who is the client, who is paying for the psychologist’s services, and who will have access to the data)—were discussed earlier in this research paper. We proceed with a discussion of the conduct of the evaluation on the assumption that adequate informed consent has been obtained.

Conduct of the Assessment

Aconducive climate is critical to collection of valid test data. In conducting their assessments, psychologists strive to create appropriate rapport with clients by helping them to feel physically comfortable and emotionally at ease, as appropriate to the context. The psychologist should be well-prepared and work to create a suitable testing environment. Most psychological tests are developed with the assumption that the test takers’ attitudes and motivations are generally positive. For example, attempting to collect test data in a noisy, distracting environment or asking a client to attempt a lengthy test (e.g., an MMPI-2) while the client is seated uncomfortably with a clipboard balanced on one knee and the answer form on another would be inappropriate.

The psychologist should also consider and appreciate the attitudes of the client and address any issues raised in this regard. Some test takers may be depressed or apathetic in a manner that retards their performance, whereas others may engage in dissimulation, hoping to fake bad (i.e., falsely appear to be more pathological) or to fake good (i.e., conceal psychopathology). If there are questions about a test taker’s motivation, ability to sustain adequate concentration, or problems with the testtaking environment, the psychologist should attempt to resolve these issues and is expected to discuss how these circumstances ultimately affect test data interpretations in any reports that result from the evaluation. Similarly, in circumstances in which subtle or obvious steps by clients to fake results appear to be underway, it is important for psychologists to note these steps and consider additional instruments or techniques useful in detecting dissimulation.

Another factor that can affect the test-taking environment is the presence of third-party observers during the interview and testing procedures. In forensic evaluations, psychologists are occasionally faced by a demand from attorneys to be present as observers. Having a third-party observer present can compromise the ability of the psychologist to follow standardized procedures and can affect the validity and reliability of the data collection (McCaffrey, Fisher, Gold, & Lynch, 1996; McSweeney et al., 1998). The National Academy of Neuropsychology has taken a position that thirdparty observers should be excluded from evaluations (NAN, 2000b). A reasonable alternative that has evolved in sexual abuse assessment interviewing, in which overly suggestive interviewing by unskilled clinicians or the police is a wellknown problem, can include video recording or remote monitoring of the process when appropriate consent is granted. Such recording can have a mixed effect. It can be very useful in demonstrating that a competent evaluation was conducted, but it can also provide a strong record for discrediting poorquality work.

Data Collection and Report Preparation

Psychologists are expected to conduct assessments with explicit knowledge of the procedures required and to adhere to the standardized test administration prescribed in the relevant test manuals. In some contexts—particularly in neuropsychological assessment, in which a significant number and wide range of instruments may be used—technicians are sometimes employed to administer and score tests as well as to record behaviors during the assessment. In this situation, it is the neuropsychologist who is responsible for assuring adequacy of the training of the technician, selecting test instruments, and interpreting findings (see National Academy of Neuropsychology [NAN], 2000a). Even in the case of less sophisticated evaluations (e.g., administration of common IQ or achievement testing in public school settings), psychologists charged with signing official reports are responsible for assuring the accuracy and adequacy of data collection, including the training and competence of other personnel engaged in test administration. This responsibility is especially relevant in circumstances in which classroom teachers or other nonpsychologists are used to proctor group-administered tests.

Preparation of a report is a critical part of a psychological assessment, and the job is not complete until the report is finished; this sometimes leads to disputes when payment for assessment is refused or delayed. Although it is not ethically appropriate to withhold a completed report needed for critical decision making in the welfare of a client, psychologists are not ethically required to prepare a report if payment is refused. Many practitioners require advance payment or a retainer as a prerequisite for undertaking a lengthy evaluation. In some instances, practitioners who have received partial payment that covers the time involved in record review and data collection will pause prior to preparing the actual report and await additional payment before writing the report. Such strategies are not unethical per se but should be carefully spelled out and agreed to as part of the consent process before the evaluation is begun. Ideally, such agreements should be made clear in written form to avoid subsequent misunderstandings.

Automated Test Scoring and Interpretation

The psychologist who signs the report is responsible for the contents of the report, including the accuracy of the data scoring and validity of the interpretation. When interpreting assessment results—including automated interpretations— psychologists must take into account the purpose of the assessment, the various test factors, the client’s test-taking abilities, and the other characteristics of the person being assessed (e.g., situational, personal, linguistic, and cultural differences) that might affect psychologists’ judgments or reduce the accuracy of their interpretations. If specific accommodations for the client (e.g., extra time, use of a reader, or availability of special appliances) are employed in the assessment, these accommodations must be described; automated testing services cannot do this. Although mechanical scoring of objective test data is often more accurate than hand scoring, machines can and do make errors. The psychologist who makes use of an automated scoring system should check the mechanically generated results carefully.

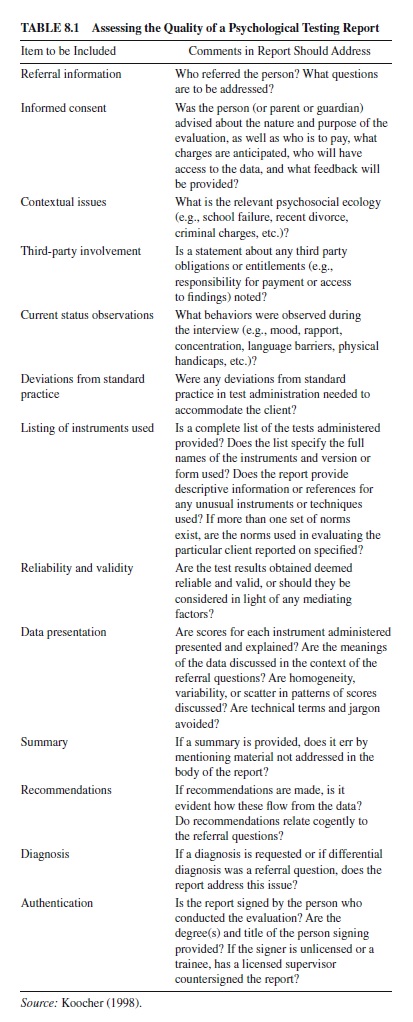

Psychologists are ethically responsible for indicating any significant reservations they have about the accuracy or limitations of their interpretations in the body of their reports, including any limitations on automated interpretative reports that may be a part of the case file. For example, psychologists who obtain computer-generated interpretive reports of MMPI-2 protocols may choose to use some or all of the information so obtained in their personally prepared reports. The individually prepared report of the psychologist should indicate whether a computer-assisted or interpretive report was used and explain any modified interpretations made or confirm the validity of the computerized findings, as appropriate.Asummary of criteria helpful in evaluating psychological assessment reports (Koocher, 1998) is presented in Table 8.1.

After the Evaluation

Following completion of their evaluations and reports, psychologists often receive requests for additional clarification, feedback, release of data, or other information and materials related to the evaluation. Release of confidential client information is addressed in the ethics code and highly regulated under many state and federal laws, but many other issues arise when psychological testing is involved.

Feedback Requests

Psychologists are expected to provide explanatory feedback to the people they assess unless the nature of the client relationship precludes provision of an explanation of results. Examples of relationships in which feedback might not be owed to the person tested would include some organizational consulting, preemployment or security screening, and some forensic evaluations. In every case the nature of feedback to be provided and any limitations must be clearly explained to the person being assessed in advance of the evaluation. Ideally, any such limitations are provided in both written and oral form at the outset of the professional relationship. In normal circumstances, people who are tested can reasonably expect an interpretation of the test results and answers to questions they may have in a timely manner. Copies of actual test reports may also be provided as permitted under applicable law.

Requests for Modification of Reports

On some occasions, people who have been evaluated or their legal guardians may request modification of a psychologist’s assessment report. One valid reason for altering or revising a report would be to allow for the correction of factual errors. Another appropriate reason might involve release of information on a need-to-know basis for the protection of the client. For example, suppose that in the course of conducting a psychological evaluation of a child who has experienced sexual abuse, a significant verbal learning disability is uncovered. This disability is fully described in the psychologist’s report. In an effort to secure special education services for the learning problem, the parents of the child ask the psychologist to tailor a report for the school focusing only on matters relevant to the child’s educational needs—that is to say, the parents would prefer that information on the child’s sexual abuse is not included in the report sent to the school’s learning disability assessment team. Such requests to tailor or omit certain information gleaned during an evaluation may be appropriately honored as long as doing so does not tend to mislead or misrepresent the relevant findings.

Psychologists must also be mindful of their professional integrity and obligation to fairly and accurately represent relevant findings. A psychologist may be approached by a case management firm with a request to perform an independent examination and to send a draft of the report so that editorial changes can be made. This request presents serious ethical considerations, particularly in forensic settings. Psychologists are ethically responsible for the content of all reports issued over their signature. One can always listen to requests or suggestions, but professional integrity and oversight of one’s work cannot be delegated to another. Reports should not be altered to conceal crucial information, mislead recipients, commit fraud, or otherwise falsely represent findings of a psychological evaluation. The psychologist has no obligation to modify a valid report at the insistence of a client if the ultimate result would misinform the intended recipient.

Release of Data

Who should have access to the data on which psychologists predicate their assessments? This issue comes into focus most dramatically when the conclusions or recommendations resulting from an assessment are challenged. In such disputes, the opposing parties often seek review of the raw data by experts not involved in the original collection and analyses. The purpose of the review might include actual rescoring raw data or reviewing interpretations of scored data. In this context, test data may refer to any test protocols, transcripts of responses, record forms, scores, and notes regarding an individual’s responses to test items in any medium (ECTF, 2001). Under long-standing accepted ethical practices, psychologists may release test data to a psychologist or another qualified professional after being authorized by a valid release or court order. Psychologists are exhorted to generally refrain from releasing test data to persons who are not qualified to use such information, except (a) as required by law or court order, (b) to an attorney or court based on a client’s valid release, or (c) to the client as appropriate (ECTF, 2001). Psychologists may also refrain from releasing test data to protect a client from harm or to protect test security (ECTF, 2001).

In recent years, psychologists have worried about exactly how far their responsibility goes in upholding such standards. It is one thing to express reservations about a release, but it is quite another matter to contend within the legal system. For example, if a psychologist receives a valid release from the client to provide the data to another professional, is the sending psychologist obligated to determine the specific competence of the intended recipient? Is it reasonable to assume that any other psychologist is qualified to evaluate all psychological test data? If psychologists asked to release data are worried about possible harm or test security, must they retain legal counsel at their own expense to vigorously resist releasing the data?

The intent of the APA ethical standards is to minimize harm and misuse of test data. The standards were never intended to require psychologists to screen the credentials of intended recipients, become litigants, or incur significant legal expenses in defense of the ethics code. In addition, many attorneys do not want the names of their potential experts released to the other side until required to do so under discovery rules. Some attorneys may wish to show test data to a number of potential experts and choose to use only the expert(s) most supportive of their case. In such situations, the attorney seeing the file may prefer not to provide the transmitting psychologist with the name of the intended recipient. Although such strategies are alien to the training of many psychologists trained to think as scientific investigators, they are quite common and ethical in the practice of law. It is ethically sufficient for transmitting psychologists to express their concerns and rely on the assurance of receiving clinicians or attorneys that the recipients are competent to interpret those data. Ethical responsibility in such circumstances shifts to receiving experts insofar as justifying their own competence and the foundation of their own expert opinions is concerned, if a question is subsequently raised in that regard. The bottom line is that although psychologists should seek appropriate confidentiality and competence assurances, they cannot use the ethics code as a shield to bar the release of their complete testing file.

Test Security

The current APA ethics code requires that psychologists make reasonable efforts to maintain the integrity and security of copyright-protected tests and other assessment techniques consistent with law and with their contractual obligations (ECTF, 2001). Most test publishers also elicit such a pledge from those seeking to purchase test materials. Production of well-standardized test instruments represents a significant financial investment to the publisher. Breaches of such security can compromise the publisher’s proprietary rights and vitiate the utility of the test to the clinician by enabling coaching or otherwise inappropriate preparation by test takers.

What is a reasonable effort as envisioned by the authors of the ethics code? Close reading of both the current and proposed revision of the code indicate that psychologists may rely on other elements of the code in maintaining test security. In that context, psychologists have no intrinsic professional obligation to contest valid court orders or to resist appropriate requests for disclosure of test materials—that is to say, the psychologist is not obligated to litigate in the support of a test publisher or to protect the security of an instrument at significant personal cost. When in doubt, a psychologist always has the option of contacting the test publisher. If publishers, who sold the tests to the psychologist eliciting a promise that the test materials be treated confidentially, wish to object to requested or court-ordered disclosure, they should be expected to use their own financial and legal resources to defend their own copyright-protected property.

Psychologists must also pay attention to the laws that apply in their own practice jurisdiction(s). For example, Minnesota has a specific statute that prohibits a psychologist from releasing psychological test materials to individuals who are unqualified or if the psychologist has reason to believe that releasing such material would compromise the integrity of the testing process. Such laws can provide additional protective leverage but are rare exceptions.

An editorial in the American Psychologist (APA, 1999) discussed test security both in the context of scholarly publishing and litigation, suggesting that potential disclosure must be evaluated in light of both ethical obligations of psychologists and copyright law. The editorial also recognized that the psychometric integrity of psychological tests depends upon the test taker’s not having prior access to study or be coached on the test materials. The National Academy of Neuropsychology (NAN) has also published a position paper on test security (NAN, 2000c). There has been significant concern among neuropsychologists about implications for the validity of tests intended to assess malingering if such materials are freely circulated among attorneys and clients. Both the American Psychologist editorial and the NAN position paper ignore the implications of this issue with respect to preparation for high-stakes testing and the testing industry, as discussed in detail later in this research paper. Authors who plan to publish information about tests should always seek permission from the copyright holder of the instrument and not presume that the fair use doctrine will protect them from subsequent infringement claims. When sensitive test documents are subpoenaed, psychologists should also ask courts to seal or otherwise protect the information from unreasonable public scrutiny.

Special Issues

In addition to the basic principles described earlier in this research paper (i.e., the preparation, conduct, and follow-up of the actual assessment), some special issues regard psychological testing. These issues include automated or computerized assessment services, high-stakes testing, and teaching of psychological assessment techniques. Many of these topics fall under the general domain of the testing industry.

The Testing Industry

Psychological testing is big business.Test publishers and other companies offering automated scoring systems or national testingprogramsaresignificantbusinessenterprises.Although precise data are not easy to come by,Walter Haney and his colleagues (Haney, Madaus, & Lyons, 1993) estimated gross revenues of several major testing companies for 1987–1988 as follows: Educational Testing Service, $226 million; National ComputerSystems,$242million;ThePsychologicalCorporation (then a division of Harcort General), $50–55 million; and theAmerican College Testing Program, $53 million. The Federal Reserve Bank suggests that multiplying the figures by 1.56 will approximate the dollar value in 2001 terms, but the actual revenue involved is probably significantly higher, given the increased numbers of people taking such tests by comparison with 1987–1988.

The spread of consumerism in America has seen increasing criticism of the testing industry (Haney et al., 1993). Most of the ethical criticism leveled at the larger companies fall into the categories of marketing, sales to unauthorized users, and the problem of so-called impersonal services. Publishers claim that they do make good-faith efforts to police sales so that only qualified users obtain tests. They note that they cannot control the behavior of individuals in institutions where tests are sent. Because test publishers must advertise in the media provided by organized psychology (e.g., the APA Monitor) to influence their prime market, most major firms are especially responsive to letters of concern from psychologists and committees of APA. At the same time, such companies are quite readily prepared to cry antitrust fouls when professional organizations become too critical of their business practices.

The Center for the Study of Testing, Evaluation, and Educational Policy (CSTEEP), directed by Walt Haney, is an educational research organization located at Boston College in the School of Education (http://wwwcsteep.bc.edu). CSTEEP has been a valuable ally to students who have been subjected to bullying and intimidation by testing behemoths such as Educational Testing Service and the SAT program when the students’ test scores improve dramatically. In a number of circumstances, students have had their test results canceled, based on internal statistical formulas that few people other than Haney and his colleagues have ever analyzed. Haney has been a valuable expert in helping such students obtain legal remedies from major testing companies, although the terms of the settlements generally prohibit him from disclosing the details. Although many psychologists are employed by large testing companies, responses to critics have generally been issued by corporate attorneys rather than psychometric experts. It is difficult to assess the degree to which insider psychologists in these big businesses exert any influence to assure ethical integrity and fairness to individual test takers.

Automated Testing Services

Automated testing services and software can be a major boon to psychologists’ practices and can significantly enhance the accuracy and sophistication of diagnostic decision making, but there are important caveats to observe. The draft revision of the APA code states that psychologists who offer assessment or scoring services to other professionals should accurately describe the purpose, norms, validity, reliability, and applications of the procedures and any special qualifications applicable to their use (ECTF, 2001). Psychologists who use such scoring and interpretation services (including automated services) are urged to select them based on evidence of the validity of the program and analytic procedures (ECTF, 2001). In every case, ethical psychologists retain responsibility for the appropriate application, interpretation, and use of assessment instruments, whether they score and interpret such tests themselves or use automated or other services (ECTF, 2001).

One key difficulty in the use of automated testing is the aura of validity conveyed by the adjective computerized and its synonyms. Aside from the long-standing debate within psychology about the merits of actuarial versus clinical prediction, there is often a kind of magical faith that numbers and graphs generated by a computer program somehow equate with increased validity of some sort. Too often, skilled clinicians do not fully educate themselves about the underpinnings of various analytic models. Even when a clinician is so inclined, the copyright holders of the analytic program are often reluctant to share too much information, lest they compromise their property rights.

In the end, the most reasonable approach is to use automated scoring and interpretive services as only one component of an evaluation and to carefully probe any apparently discrepant findings. This suggestion will not be a surprise to most competent psychologists, but unfortunately they are not the only users of these tools. Many users of such tests are nonpsychologists with little understanding of the interpretive subtleties. Some take the computer-generated reports at face value as valid and fail to consider important factors that make their client unique. A few users are simply looking for a quick and dirty source of data to help them make a decision in the absence of clinical acumen. Other users inflate the actual cost of the tests and scoring services to enhance their own billings. When making use of such tools, psychologists should have a well-reasoned strategy for incorporating them in the assessment and should interpret them with well-informed caution.

High-Stakes Testing

The term high-stakes tests refers to cognitively loaded instruments designed to assess knowledge, skill, and ability with the intent of making employment, academic admission, graduation, or licensing decisions. For a number of public policy and political reasons, these testing programs face considerable scrutiny and criticism (Haney et al., 1993; Sackett, Schmitt, Ellingson, & Kabin, 2001). Such testing includes the SAT, Graduate Record Examination (GRE), state examinations that establish graduation requirements, and professional or job entry examinations. Such tests can provide very useful information but are also subject to misuse and a degree of tyranny in the sense that individuals’rights and welfare are easily lost in the face of corporate advantage and political struggles about accountability in education.

In May, 2001 the APA issued a statement on such testing titled “Appropriate Use of High Stakes Testing in Our Nation’s Schools” (APA, 2001). The statement noted that the measurement of learning and achievement are important and that tests—when used properly—are among the most sound and objective ways to measure student performance. However, when tests’ results are used inappropriately, they can have highly damaging unintended consequences. High-stakes decisions such as high school graduation or college admissions should not be made on the basis of a single set of test scores that only provide a snapshot of student achievement. Such scores may not accurately reflect a student’s progress and achievement, and they do not provide much insight into other critical components of future success, such as motivation and character.

The APA statement recommends that any decision about a student’s continued education, retention in grade, tracking, or graduation should not be based on the results of a single test. The APA statement noted that

- When test results substantially contribute to decisions made about student promotion or graduation, there should be evidence that the test addresses only the specific or generalized content and skills that students have had an opportunity to learn.

- When a school district, state, or some other authority mandates a test, the intended use of the test results should be clearly described. It is also the responsibility of those who mandate the test to monitor its impact—particularly on racial- and ethnic-minority students or students of lower socioeconomic status—and to identify and minimize potential negative consequences of such testing.

- In some cases, special accommodations for students with limited proficiency in English may be necessary to obtain valid test scores. If students with limited English skills are to be tested in English, their test scores should be interpreted in light of their limited English skills. For example, when a student lacks proficiency in the language in which the test is given (students for whom English is a second language, for example), the test could become a measure of their ability to communicate in English rather than a measure of other skills.

- Likewise, special accommodations may be needed to ensure that test scores are valid for students with disabilities. Not enough is currently known about how particular test modifications may affect the test scores of students with disabilities; more research is needed. As a first step, test developers should include students with disabilities in field testing of pilot tests and document the impact of particular modifications (if any) for test users.

- For evaluation purposes, test results should also be reported by sex, race-ethnicity, income level, disability status, and degree of English proficiency.

One adverse consequence of high-stakes testing is that some schools will almost certainly focus primarily on teaching-to-the-test skills acquisition. Students prepared in this way may do well on the test but find it difficult to generalize their learning beyond that context and may find themselves unprepared for critical and analytic thinking in their subsequent learning environments. Some testing companies such as the Educational Testing Service (developers of the SAT) at one time claimed that coaching or teaching to the test would have little meaningful impact and still publicly attempt to minimize the potential effect of coaching or teaching to the test.

The best rebuttal to such assertions is the career of Stanley H. Kaplan. A recent article in The New Yorker (Gladwell, 2001) documents not only Kaplan’s long career as an entrepreneurial educator but also the fragility of so-called test security and how teaching strategies significantly improves test scores in exactly the way the industry claimed was impossible. When Kaplan began coaching students on the SAT in the 1950s and holding posttest pizza parties to debrief the students and learn about what was being asked, he was considered a kind of subverter of the system. Because the designers of the SAT viewed their work as developing a measure of enduring abilities (such as IQ), they assumed that coaching would do little to alter scores. Apparently little thought was given to the notion that people are affected by what they know and that what they know is affected by what they are taught (Gladwell, 2001). What students are taught is dictated by parents and teachers, and they responded to the highstakes test by strongly supporting teaching that would yield better scores.

Teaching Psychological Testing

Psychologists teaching assessment have a unique opportunity to shape their students’professional practice and approach to ethics by modeling how ethical issues are actively integrated into the practice of assessment (Yalof & Brabender, 2001). Ethical standards in the areas of education and training are relevant. “Psychologists who are responsible for education and training programs take reasonable steps to ensure that the programs are designed to provide appropriate knowledge and proper experiences to meet the requirements for licensure, certification and other goals for which claims are made by the program” (ECTF, 2001).Aprimary responsibility is to ensure competence in assessment practice by providing the requisite education and training.

A recent review of studies evaluating the competence of graduate students and practicing psychologists in administration and scoring of cognitive tests demonstrates that errors occur frequently and at all levels of training (Alfonso & Pratt, 1997). The review also notes that relying only on practice assessments as a teaching methodology does not ensure competent practice. The authors conclude that teaching programs that include behavioral objectives and that focus on evaluating specific competencies are generally more effective. This approach is also more concordant with the APA guidelines for training in professional psychology (APA, 2000).

The use of children and students’ classmates as practice subjects in psychological testing courses raises ethical concern (Rupert, Kozlowski, Hoffman, Daniels, & Piette, 1999). In other teaching contexts, the potential for violations of privacy are significant in situations in which graduate students are required to take personality tests for practice. Yalof and Brabender (2001) address ethical dilemmas in personality assessment courses with respect to using the classroom for in vivo training. They argue that the student’s introduction to ethical decision making in personality assessment occurs in assessment courses with practice components. In this type of course, students experience firsthand how ethical problems are identified, addressed, and resolved. They note that the instructor’s demonstration of how the ethical principles are highlighted and explored can enable students to internalize a model for addressing such dilemmas in the future. Four particular concerns are described: (a) the students’ role in procuring personal experience with personality testing, (b) identification of participants with which to practice, (c) the development of informed consent procedures for assessment participants, and (d) classroom presentations. This discussion does not provide universally applicable concrete solutions to ethical problems; however, it offers a consideration of the relevant ethical principles that any adequate solution must incorporate.

Recommendations

In an effort to summarize the essence of good ethical practice in psychological assessment, we offer this set of suggestions:

- Clients to be tested (or their parents or legal guardians) must be given full informed consent about the nature of the evaluation, payment for services, access to results, and other relevant data prior to initiating the evaluation.

- Psychologists should be aware of and adhere to published professional standards and guidelines relevant to the nature of the particular type of assessment they are conducting.

- Different types of technical data on tests exist—including reliability and validity data—and psychologists should be sufficiently familiar with such data for any instrument they use so that they can justify and explain the appropriateness of the selection.

- Those administering psychological tests are responsible for assuring that the tests are administered and scored according to standardized instructions.

- Test users should be aware of potential test bias or client characteristics that might reduce the validity of the instrument for that client and context. When validity is threatened, the psychologists should specifically address the issue in their reports.

- No psychologist is competent to administer and interpret all psychological tests. It is important to be cautiously self-critical and to agree to undertake only those evaluations that fall within one’s training and sphere of competence.

- The validity and confidence of test results relies to some degree on test security. Psychologists should use reasonable caution in protecting the security of test items and materials.

- Automated testing services create a hazard to the extent that they may generate data that are inaccurate for certain clients or that are misinterpreted by improperly trained individuals. Psychologists operating or making use of such services should take steps to minimize such risks.

- Clients have a right to feedback and a right to have confidentiality of data protected to the extent agreed upon at the outset of the evaluation or in subsequent authorized releases.

- Test users should be aware of the ethical issues that can develop in specific settings and should consult with other professionals when ethical dilemmas arise.

Bibliography:

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., Sechrest, L., & Reno, R. R. (1990). Graduate training in statistics, methodology and measurement in psychology: Asurvey of PhD programs in North America. American Psychologist, 45, 721–734.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (1953). Ethical standards of psychologists. Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (1992). Ethical standards of psychologists and code of conduct. Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (1999). Test security: Protecting the integrity of tests. American Psychologist, 54,

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2000). Guidelines and principles for accreditation of programs in professional Psychology. Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2001). Appropriate use of high stakes testing in our nation’s schools. Washington, DC: Author.

- Ardila, A., & Moreno, S. (2001). Neuropsychological test performance in Aruaco Indians: An exploratory study. Neuropsychology, 7, 510–515.

- British Psychological Society (BPS). (1995). Certificate statement register: Competencies in occupational testing, general information pack (Level A). (Available from the British Psychological Society, 48 Princess Road East, Leicester, England LEI 7DR)

- British Psychological Society (BPS). (1996). Certificate statement register: Competencies in occupational testing, general information pack (Level B). (Available from the British Psychological Society, 48 Princess Road East, Leicester, England LEI 7DR)

- Ethics Code Task Force (ECTF). (2001). Working draft ethics code revision, October, 2001. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ ethics.

- Eyde, L. E., Moreland, K. L., Robertson, G. J., Primoff, E. S., & Most, R. B. (1988). Test user qualifications: A data-based approach to promoting good test use. Issues in scientific psychology (Report of the Test User Qualifications Working Group of the Joint Committee on Testing Practices). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Eyde,L.E.,Robertson,G.J.,Krug,S.E.,Moreland,K.L.,Robertson, A.G.,Shewan,C.M.,Harrison,P.L.,Porch,B.E.,Hammer,A.L., & Primoff, E. S. (1993). Responsible test use: Case studies for assessing human behavior. Washington, DC: American PsychologicalAssociation.

- Flanagan, D. P., & Alfonso, V. C. (1995). A critical review of the technical characteristics of new and recently revised intelligence tests for preschool children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 13, 66–90.

- Gladwell, M. (2001, December 17). What Stanley Kaplan taught us about the S.A.T. The New Yorker. Retrieved from http://www .newyorker.com/PRINTABLE/?critics/011217crat_atlarge

- Grisso,T., &Appelbaum, P. S. (1998). Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grote, C. L., Lewin, J. L., Sweet, J. J., & van Gorp, W. G. (2000). Courting the clinician. Responses to perceived unethical practices in clinical neuropsychology: Ethical and legal considerations. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 14, 119–134.

- Haney, W. M., Madaus, G. F., & Lyons, R. (1993). The fractured marketplace for standardized testing. Norwell, MA: Kluwer.

- Heaton, R. K., Grant, I., & Matthews, C. G. (1991). Comprehensive norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographic corrections, research findings, and clinical applications. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- International Test Commission. (2000). International guidelines for test use: Version 2000. (Available from Professor Dave Bartram, President, SHL Group plc, International Test Commission, The Pavilion, 1 Atwell Place, Thames Ditton, KT7, Surrey, England)

- Johnson-Greene, D., Hardy-Morais, C., Adams, K., Hardy, C., & Bergloff, P. (1997). Informed consent and neuropsychological assessment: Ethical considerations and proposed guidelines. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 11, 454–460.