View sample media research paper on radio and TV programming. Browse media research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Programming is at the heart of radio and television operations. Various distribution techniques (terrestrial broadcast, cable TV, subscription TV, satellite radio, Internet, etc.) come and go. But one thing remains constant: the need for desirable content. This need is constantly increasing. In the 1920s, there were fewer than 400 radio stations (White, 2003), and today there are more than 13,000 AM and FM stations (Regents, 2003), most of them operating on a 24-hour basis. In addition, there is satellite radio, cable radio, Internet radio, and podcasting, all of which need audio content. In the television realm, NBC aired 601 hours of programming during 1939, its first year of broadcast (Shanks, 1976, p. 65). By 1979 it was airing 7,000 hours per year (Auletta, 1991, p. 93). Add to that the many hundreds of broadcast and cable networks, satellite television, Web sites, and other forms of distribution, and it is easy to see that the appetite for program material is insatiable.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

People involved with programming are the ones who initiate content ideas or solicit them from others. From the idea stage, they develop the concept into a workable product that people will want to watch or listen to. They then decide how best to make the program available by planning its scheduling and distribution. At some point, they evaluate the effectiveness of their work and make changes, if necessary. Meanwhile, of course, they are initiating, developing, and scheduling new programming projects.

This research paper will discuss these various processes related to programming, pointing out similarities and differences among the various distribution channels. It will describe where programming comes from, how it finds its way to an increasingly elusive and fragmented audience, and how the programming process might change in the future. But first, to set the stage, here is a short history of programming.

A Short History of Programming

The concept of programming did not exist when radio first started in the 1920s. The novelty of radio was such that people would stay glued to the earphones of their huge batteryoperated sets just to hear someone reciting call letters from an early radio station. Free talent wandered into stations to sing, recite poetry, or play musical instruments, but eventually the novelty wore off, and performers wanted to be paid. After stumbling through several experiments, radio practitioners settled on advertising as a means of raising money, despite the fact that the then–Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover opposed advertising saying, “It is inconceivable that we should allow so great a possibility for service to be drowned in advertising chatter” (Barnouw, 1966, p. 96).

Advertising chatter, however, prevailed, and in the 1930s, most of the programming was undertaken by advertising agencies. Several networks (NBC, CBS, ABC) had been formed to distribute programs to stations throughout the country, and advertising agencies bought blocks of time and filled the time with programming and mentions of the sponsor and its product line. Often the product became part of the story line—the show’s announcer would visit Fibber McGee and Molly and talk about waxing the floor with Johnson’s Wax. The advertisers came up with concepts, hired the talent, and oversaw production. They paid the networks to distribute the programming, but the networks did little programming decision making. As long as the advertiser was happy with the program and its time slot, it was left alone. As a result, many programs aired on radio for years. For example, Jack Benny was on radio from 1932 to the mid-1950s at 7:30 p.m., Sunday, sponsored primarily by Jell-O.

When television started in earnest in the late 1940s, it adopted the same model. Advertising agencies provided the networks with Texaco Star Theater, Kraft Television Theater, Alcoa Hour, and many other similarly named shows. But television production proved more expensive than radio production, so it was difficult for one sponsor to pay all the costs associated with a weekly series. The old advertising-agency-dominated programming model started to fray. In some instances, several companies would share the costs, and the program would be “brought to you by Buick, Lucky Strike cigarettes, and Ivory soap.” The downside of this was that viewers did not identify the program with the product as they had during radio’s heyday (Sterling & Kittross, 1990, p. 161).

Then came the quiz show scandals of the late 1950s. Quiz shows, where contestants locked in soundproof booths agonized as they tried to answer difficult questions, were big moneymakers for advertisers. Audiences were large and engaged to the extent that products from Revlon, which sponsored The $64,000 Question, sold out nationwide. When it was discovered that popular contestants had been coached to keep them on the air, Americans’ trust of television plummeted. There were many speculations about who knew about this coaching— advertisers, agency executives, TV network programmers, but the end result was that television executives decided to take charge of their programming rather than depending on the advertising agencies to supply it to them (Goodwin, 1989, pp. 51–52).

Actually, the trend toward broadcaster control of programming had started before the late 1950s. When television became popular in the late 1940s, it took away most of radio’s prime network shows and the talent associated with them. Radio had to reinvent itself and did so mainly by programming music hosted by local disc jockeys who appealed to the new radio audience—teenagers. Radio became a locally based medium, with different stations emphasizing formats of music rather than individual programs. This style of programming was not conducive to sponsorship by individual advertisers. Rather, the stations began selling ads (called spots) for insertion within their programming. The programming decisions rested with local program managers and station managers.

In the television of the mid-1950s, there were strongminded executives who wanted to control their own programming. One was Sylvester L. “Pat” Weaver who, while president of the NBC from 1953 to 1955, devised what he called the magazine concept. Advertisers bought commercial insertions in programs such as “Today” or “Tonight” and had no say about content. But it was the quiz scandals that pushed program decision making from the ad agencies to the TV executives (Peyser, 1979).

Network executives now began to consider their programming schedule as an overall entity. They developed strategies—some to keep the audience watching their particular network throughout the evening, some to get viewers to sample programming, all to increase their revenue and recognition. Audience measurement became important, and executives canceled shows that did not have adequate ratings. They created broadcast standards and practices departments to function as internal censors to keep off objectionable programming with the intent of reassuring the public that responsible people were minding the store. Networks and stations still worked with advertising agencies to obtain ads, but it was the broadcasters who were in the programming driver’s seat. Throughout the 1960s, this was a very lucrative driver’s seat, not only for ABC, CBS, and NBC but also for local TV stations, because most of them were affiliated with a network.

Then several things happened that complicated programming decision making for network executives. In 1970, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) took a look at TV network programming practices and decided that the networks had too much power. Not only did they produce and own much of the programming, but when they did buy programs from independent sources (such as Norman Lear’s Tandem-TAT or Aaron Spelling Productions), they usually established financial interest in that programming and received part of the profit when the show was sold in syndication for reruns. The FCC thought that this gave the networks too much power, and so it instituted financial interest and domestic syndication (fin-syn) rules that barred networks from having a financial interest in programs produced by outside companies and forbade the networks from receiving money from syndication. The FCC also imposed limits on how much of their own programming networks could produce themselves. All this led to a healthy independent production landscape, wherein proprietors of small companies could pitch ideas to network programming executives and make substantial money when the programs were aired and rerun, but the networks’ profits declined (Vane & Gross, 1994, pp. 55–57).

Something else that happened in the 1970s was that the number of independent television stations grew. Prior to the 1970s, most of the TV stations had been affiliated with ABC, CBS, or NBC, and those that weren’t aired primarily network reruns. The FCC, mainly because technology had improved, authorized many additional TV stations in the early 1970s. These stations strived to do something new that was not on the networks. Some of them capitalized on movies or local interests, and many bought “first-run” programs—ones sold by independent production companies and syndicators who produced the shows with the idea that they would be shown on stations as opposed to the networks. Independent stations grew from 28 in 1961 to 103 in 1979 and to 339 in 1989 (INTV, 1990). This growth further fueled the independent production companies and also cut down, to some degree, network viewership.

Public television and radio came to the fore after the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 made them viable entities (Avery & Pepper, 1980). This further increased viewing and listening options, but it also enabled the networks and stations to try to reduce their public service programming, stating that public broadcasting was there to fill that need. Also, several new broadcast commercial networks (Fox, then UPN and WB, which merged into CW) emerged to further erode the TV audience of the original three networks.

The real force to fragment viewing, however, was cable TV, which exploded during the 1980s. Once a sleepy form of distribution meant to extend the range of TV stations’ signals, it came into its own after satellites were developed. These satellites were able to transmit multiple networks (HBO, Showtime, ESPN, CNN, etc.) to cable TV headends, and from there they were sent by wire to subscribers’ homes. The number of cable TV networks rose from 8 in 1980 to 290 in 2003 (Hofmeister, 2003). Program decision making at these networks differed from that of the broadcast networks. Rather than trying to obtain the largest possible audience like the networks did, the cable networks went after niche audiences—children, sports fans, adherents to a particular religion. Cable networks adopted or revised some of the broadcast network programming strategies and created some of their own.

One of the offshoots of cable TV’s popularity was that the broadcast networks were able to convince the FCC that they were no longer the powerful forces they had been in the 1960s. They pointed out that they were being hamstrung by the fin-syn rules because they were not able to produce and profit from the programs they aired, whereas the cable networks had no such restrictions. In 1995, the FCC agreed with the broadcast networks and abolished fin-syn (Bielby & Bielby, 2003). What happened, of course, was that the broadcast networks began producing much of their own programming, cutting down the amount of work available for independent production companies.

Meanwhile radio was slowly changing from a local medium to a national one, but one that was very different from original radio. Congress passed the Telecommunication Act of 1996, allowing companies to own more radio and TV stations than in the past. Several companies started on a radio-station-buying spree and wound up programming many stations but still giving them a local feel. Among other tactics, they developed voice tracking, wherein one announcer would, at one sitting, read material for many stations, making it sound local with local weather forecasts and the like. This material would be interspersed with music played on all the stations. The whole radio network and syndication market grew as the demand for programs that were not truly locally produced expanded (Perebinossoff, Gross, & Gross, 2005, p. 16).

The 21st century has seen a variety of distribution forms emerge—satellite TV, satellite radio, the Internet, cell phones, iPods. With digital video recorders, CDs, DVDs, and various other consumer goods, people can “program” for themselves, deciding when they want to watch or listen to particular material. Ordinary individuals can also participate as sources of programming to a much greater extent. But content is still king; people must come up with ideas that interest others, and these ideas must be taken through a process so that they can reach an audience. That is what programming is all about.

Sources for Program Ideas

Program ideas can come from just about anywhere—a newspaper story, a dream a TV executive has, something overheard in an elevator, a best-selling book. However, simply having a good idea does not make a TV series. Most ideas must be funneled through an organized structure of suppliers that provide the money and technical and production know-how to make programming a reality. Yes, several friends can shoot and edit a 2-minute production starring their dogs and put it on YouTube, but that is not likely to be financially rewarding. It takes companies with “deep pockets” to withstand the many programming failures while awaiting the next big hit.

In the media business, the people in stations and networks (both cable and broadcast) come up with ideas for much of their own programming. ESPN executives, for example, decide which sports events they want to telecast and then bid against other networks for the rights to cablecast the event. Producers on the staff at NBC decide what items will be included in each Today show. In the same manner, local TV station employees decide what will be aired on their 5:00 p.m. newscast, and radio station programmers select music to play. Sometimes a network executive will come up with an idea (e.g., a reality show featuring ex-cops) and then hire someone from the outside who has a successful track record to actually execute the idea. In recent years, networks have merged with movie studios (ABC/Disney, CBS/Paramount, NBC/Universal, CW/Warner). In a symbiotic relationship, the network executives use the studios to produce programs, and executives at the studios take their ideas to the network.

Television outlets also get ideas and programs from independent production companies. Known as “indies,” these are usually small companies whose owners function as the chief creative contributors—Steven Bocho, Robert Greenwald, Jerry Bruckheimer, David E. Kelley. These people come up with ideas and pitch them to the network executives, who then decide whether or not they like the idea. Since the abolishment of fin-syn, these indies get less work from the broadcast networks than they used to, but they are still hired for some projects, and they pitch to cable networks and other forms of distribution. Sometimes these indie companies have umbrella deals with the larger major movie production studios. They are housed on the studio lot, and the studio helps finance and sell the indie products in return for sharing in any financial success. For example, John Wells’s company (ER, The West Wing) is housed on the Warner lot, and Dick Wolf (Law & Order) is with Universal (Perebinossoff et al., 2005, p. 30).

The major studios and the indies sell the program to whoever will buy it. It helps to have an ownership relationship with a particular network, but there is nothing to keep Universal from selling an idea to ABC, even though it is part of NBC Universal. In addition, the movie studios supply their theatrical movies to whichever entities will buy them—CBS, Lifetime, Showtime, Netflix, and so on.

There are many other sources stations and networks can look to as they are trying to fill all their hours with programming. A number of them research and use programming from other countries. Public radio and television have aired a great deal from England, as has A&E, and there are cable channels and radio stations that program material specifically from another country. In addition, American companies often coproduce with other countries, in part so that the program or series will have a good chance of airing in all the participating countries.

Syndicators are also a source of programming material. These are companies that package material from other sources and create some themselves. They may, for example, purchase rights to 10 movies from Paramount and package them as “adventure movies” to be run on TV stations. The programs that are produced for TV syndication tend to be game shows, talk shows, and tabloid news such as Wheel of Fortune, The Oprah Winfrey Show, and Entertainment Tonight. For radio, many talk shows, such as Rush Limbaugh and Dr. Laura, are syndicated. The line between network and syndicator is blurred in radio in that both offer programs that radio stations can cherry-pick (Keith, 2004, pp. 330–333).

On occasion, advertisers still come up with programming ideas, such as Hallmark Hall of Fame. In fact, some stations and networks choose to air infomercials, which are really 30-minute advertisements that appear to be information shows because they include interviews and demonstrations related to a particular product.

Companies that own many TV or radio stations sometimes come up with a programming idea and try it on one station. If it is successful, it becomes a programming idea for all the other owned stations.

The Internet is awash with ideas for programs. Every computer has the potential to be a source for program material. Many conventional distribution forms such as networks and syndicators are putting programs or parts of programs on the Internet (and cell phones, iPods, and other electronic gadgets), as well as their usual channels. Hundreds of individuals have established Internet-only radio stations and programming on YouTube, which would have been unheard of in the past. Just where all this will lead in terms of idea generation is yet to be determined. But new ideas are always welcome. Anyone who has had a programming job that involves coming up with material to fill a channel 24 hours a day 365 days a year will attest to that.

The Development Process

Once programmers feel that they have found a good idea, be it one of their own or one pitched by someone else, they must shape, fine-tune, and perfect it so that it is ready for public consumption. This process is called development— sometimes referred to as “development hell.” Many people find it hellish because it is time intensive and very costly and the odds for success are exceedingly slim. It is difficult to develop a TV series that has the potential to make millions of dollars in syndication, a radio format that will bring a station from Number 10 in the ratings to Number 1, or a new reality show that will be first in its time period.

Development differs from medium to medium and project to project, but there are a number of steps commonly taken. One of these is obtaining rights, especially if the idea is based on a book or a person’s life. This step should definitely involve legal counsel that can draw up a contract stipulating the nature and duration of the agreement, any compensation that will be given and how it will be distributed, how the credits will read, whether the purchaser can assign rights to another party, and other important stipulations. One tricky decision involves when to ask for the rights. Ideally, the person with the idea should have rights even before pitching the idea so that securing rights does not slow down the development process. But obtaining even tentative rights usually costs money, and then if the project goes nowhere, that money is lost.

To help move some projects through development, it is wise to attach a well-known star, writer, director, or executive. The downside is that the well-known people attached may not be right for the idea, and once they have been attached they are hard to get rid of. Sometimes it is better (and cheaper) to go with unknowns who can become stars, such as happened with the cast of Friends.

The pitch that is made for a project is very important and sets the stage for many other factors related to development. Whether the pitch is coming from an independent production company, a radio station disc jockey, a programming vice president trying to convince a network president, or anyone else, it should have an easily understood concept. Sometimes this concept is referred to as a log line because it is often what winds up on various program guides that describe a show in 25 words or less. It must be attention getting, informative, pithy, and short— something that both a busy executive and a potential audience member can grasp easily. Many successful log lines start with “when” or “after”—“When a stockbroker’s life is threatened, he . . .” or “After the woman has been jilted by her long-time lover, she . . .” Other things people should think of before pitching an idea to someone else include the following: Who are the main characters? What are the conflicts? How are the conflicts resolved? What is the opening scene? How can the show (or series, or format) be promoted?

It is difficult for a newcomer to get a pitch meeting with a high-level network executive (Koch, Kosberg, & Norman, 2004, pp. 81–88). Usually, executives want to deal with well-established people. Those without a wellestablished track record are apt to meet with low-level executives who then pitch the idea to their bosses. Often it takes a telephone prepitch to get into the door. The seller gives a very brief rundown after which the programming executive may tell the seller that there is no interest in the idea or may invite the person in for a more detailed pitch. On the other hand, some programming executives demand that their staff members come up with frequent program ideas—in essence, doing an internal pitch as often as once a week.

If the pitch is from an external production company, there will usually be a number of sellers present—perhaps the company owner, a writer, and a producer—and there may be one or several people listening to the pitch. After the initial small talk, the sellers have about 5 minutes to lay out their characters, sample scenes, and other elements that show that they have a solid proposal. The buyers ask questions for which the sellers should have answers. If all goes well, the buyers will ask for more information, perhaps a treatment that further outlines the idea or even a sample script. The buyer’s and seller’s lawyers will draw up a contract, and the development process will move along with the buyer picking up much, but not all, of the cost. The project can be axed at many points, but if it makes it through several paper-based stages, the seller will probably be asked to produce a pilot consisting of one produced show that is supposed to be representative of the series.

Once a pilot is produced, it is tested, usually in a small auditorium. A group of people are shown the program and asked to fill out questionnaires or in other ways give their opinions. The ideal audience for testing most programs is a cross-section of Americans, so testing sites are often set up at places where tourists from all over the country are likely to congregate—Las Vegas, Universal Studios, Hollywood Boulevard. Testing is a nervous time for the project creators because a bad test can kill their dreams. Sometimes a test will show that the concept is sound but the idea needs some tweaking. The network will ask the show creator (which may be itself) to make some changes and then test the program again (Perebinossoff et al., 2005, pp. 99–121).

The type of development just described is common for broadcast and cable TV series and for some radio programs. There are variations for other types of programs and distribution outlets; for example, a network movie of the week would not have a pilot because it is not a series. Radio is more concerned with developing format ideas rather than developing individual programs. Syndicators often pitch material that has already been produced but that they have packaged in an original manner. The main form of testing for radio involves having people who are regular listeners assess music to help the station programmers decide what music to include and when it is time to stop playing certain selections because people are tired of them. The Internet is still the “Wild West”; on the one hand, individuals can put up programs that exhibit self-expression while on the other, traditional program providers are using methods similar to what they have used in the past for broadcast and cable networks.

The end result of conventional development, however, is a decision, usually made by high-level executives from programming, sales, research, promotion, and other areas. They consider all the programs that made it to the pilot stage (or all the possible formats or syndicated packages) with an eye to their quality and the needs of the particular media outlet they are programming. They decide which programs are worthy of being put on the air, which might be held in abeyance so that they can be replacements for shows that fail, and which should be dropped all together. For many networks, the most intense decision-making time is in the spring, when they are deciding programs for the fall schedule, but nowadays programming decisions are made year round. Often executives work with a large chart that shows all the time periods they need to program. The names of all the shows, both proposed new programs and series from the past that are being considered for continuation, are often on magnetic cards, and the executives move them around the chart until they are happy with the overall schedule. Sometimes a program will be eliminated, not because it is a weak show but because it does not fit the scheduling needs of the network (Adams, 1993).

In this manner, the development process is tied to and flows into scheduling. New programs have ostensibly been shaped and perfected and are ready for public consumption. Now the executives must decide the best way for all their programs to find their audience.

Scheduling Strategies

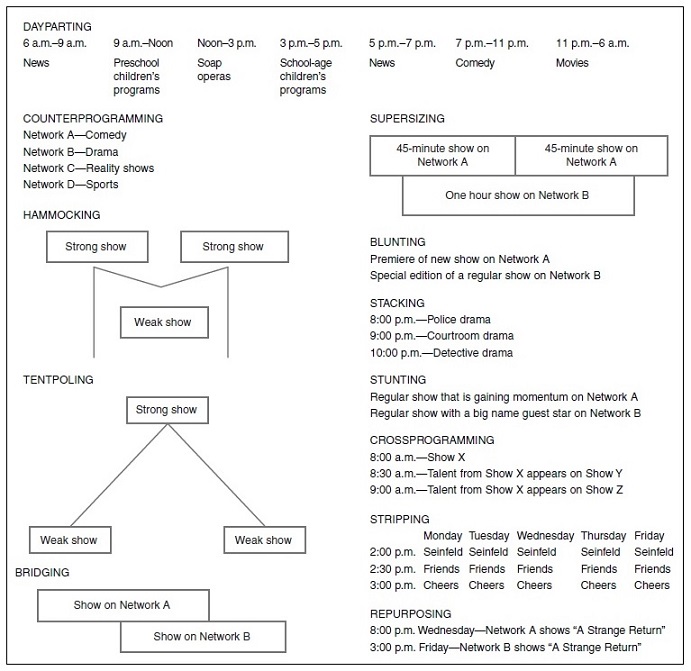

Most scheduling strategies are designed to attract and keep an audience. They are undertaken in an attempt to beat the competition and also pair segments of the public with the type of entertainment and information they will enjoy. As scheduling strategies have evolved, they have been given interesting names, such as dayparting, counterprogramming, hammocking, tentpoling, bridging, supersizing, blunting, stacking, stunting, crossprogramming, stripping, and repurposing (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Scheduling Strategies

Dayparting is undertaken by many media programmers. People’s needs, activities, and moods change throughout the day, and dayparting takes this into account by changing what is programmed and how it is presented (Blumenthal & Goodenough, 1991, p. 111).

When people first wake up in the morning, they want information to help them plan the day. As a result, radio stations air more news, weather, and traffic in the morning than during other parts of the day. Because most people go to work, they do not have a great deal of time to spend with media. So early-morning TV shows are divided into short segments. Early morning is also a good time to program for children as they often watch TV while their parents get ready for work. As the morning wears on, people who spend time with the media can do so in a more leisurely fashion, so radio is heavier on music, while game shows, talk shows, and soaps dominate TV. Late-afternoon is another good time to program for children, and radio’s evening drive time has modest increases in news and traffic information. Evening is the main time for leisurely TV viewing, and segmented talk shows are popular as people are getting ready for bed. Weekend programming is different from weekday programming, generally containing more sports. Of course, some channels don’t daypart as much as others. Children’s channels such as Disney and Nickelodeon program to children all day long, but they daypart to some extent in that they program to different ages at different times. For example, they target preschoolers during the time that other children are in school.

Counterprogramming involves airing a form or genre of programming that has a different appeal than what the competition is airing. For example, if NBC is airing dramas on Tuesday nights, CBS might offer comedies, ABC sports, and Fox reality shows. In the days of three or four networks, counterprogramming was fairly easy, and although certain blockbusters such as I Love Lucy, The Cosby Show, and Dallas tended to attract large portions of the audience, in general each network was able to attract a different group of viewers. Today, it is impossible to counterprogram all the networks that exist, but the broadcast networks still tend to counterprogram each other, and some of the niche cable channels that are similar (i.e., Discovery and A&E) have periods of counterprogramming,

Hammocking involves placing a new or weak program between two strong programs in the hope of strengthening the audience of the middle program because it gets passalong viewing from the preceding program and anticipated entertainment from the following program. For example, when NBC introduced A Different World, it hammocked it between The Cosby Show and Cheers.

Tentpoling is similar, except that the new or weak program has only one hit program assisting it—usually the program preceding it. For example, in 1976, ABC had the smash hit Happy Days at 8:00 p.m. on Tuesdays. When it introduced the spinoff Laverne and Shirley, it placed the program at 8:30 p.m. on Tuesdays. Both hammocking and tentpoling are still valid strategies. People are likely to be tempted to watch something that is scheduled close to a favorite show. Even people with digital video recorders (DVRs) get to see teasers for the next show that might entice them to set their DVR to record it the next week.

Bridging is a technique used by one network to keep audience members from sampling a program on another network. The most effective way is to have something exciting under way when the competitor’s program starts. If one network starts an hour program at 8:30 p.m., knowing that the competition is starting a strong program at 9:00 p.m., the first network may be able to have people so involved in its program that they do not switch networks.

Supersizing is a more recent version of bridging that involves adding 10 or 15 minutes to a show in order to bridge the start of a competitor’s show. In 2003, NBC aired supersized versions of Friends and Will & Grace in an effort to cut into CBS’s Survivor audience.

Blunting is a cousin of bridging and supersizing in that its purpose is to keep people from sampling the fare of the competition. When one network knows that another is planning to launch an important series, the first network can blunt the introduction by having a particularly attractive element in its own programming. For example, in 2001, NBC programmed a special edition of Fear Factor to try to hurt the premier of CBS’s The Amazing Race.

Stacking is a tactic used to try to establish audience flow—keeping audience members from one program to another (Webster, 2006). Usually, it is undertaken by programming shows that will attract people with a particular interest for a considerable block of time. PBS has frequently stacked three cooking shows in a row on a Saturday.

Stunting involves inserting entertainment elements not normally associated with a series into a show to obtain a ratings spike. Sometimes this is undertaken to blunt a competitive show, but it may also be done because competition is picking up momentum, because it is a major ratings period, or because, for whatever reason, the show needs an injection of audience appeal. One way to stunt is to have a big name movie personality, sports star, or other celebrity appear in the show. Another is to program a multipart program with cliffhangers at the end of each episode. Weddings on TV are always popular and good fodder for stunting. A major stunt occurred in March of 1980, when, in the last episode of the season, J. R. Ewing, the unscrupulous oil magnate of Dallas, was shot by an unknown assailant and rushed to the hospital. For many months, fans wondered who had shot J. R. The first episode of the fall season, the one that revealed the shooter, was not shown until November 1980, and the fervor was such that it had one of the highest ratings in TV history (Garner, 2002, pp. 34–37).

Crossprogramming is an interconnection of two shows for mutual benefit, generally involving shows produced by the same production company or network. Usually, it involves a storyline that starts on one show and ends on another. For example, in November 1991, NBC’s The Golden Girls opened the Saturday evening programming with an episode about a hurricane that was about to hit Miami, where the Golden Girls characters lived. The show after The Golden Girls was Empty Nest, and one of the Golden Girls cast members dropped in on that show to warn the characters about the hurricane. During the third show of the night, Nurses, another Golden Girls cast member volunteered to help at a local hospital. All three programs were produced by Witt/Thomas/Harris, making the interconnection possible.

Stripping is a strategy used mostly by local stations and cable networks wherein episodes of the same program are shown at the same time every weekday and sometimes also during the weekend. It is particularly common when a station or network shows reruns of a series that has been shown before, on either a broadcast or a cable network. An example would be USA network’s stripping reruns of Law & Order: Criminal Intent at 7:00 p.m. each evening. It is a useful strategy because audience members know when and where to find a favorite program.

Repurposing is a glorified method of rerunning. Rerunning usually refers to repeating a program on the same network where it was originally shown or reshowing it much later when it is syndicated. Repurposing involves rerunning a show on a different outlet shortly after its initial airing to maximize the show’s worth. For example, in 1999, ABC’s Once and Again was aired on Lifetime just a couple of days after its ABC airing. The term repurposing is used when programs are streamed on the Internet shortly after being aired on a network or station.

This list certainly does not exhaust possible programming strategies. Many new programming ideas are surfacing as a result of media forms (the Internet, iPods, cell phones) that allow people to access programs when they want to see them, sometimes referred to as video-on-demand. In part, conventional media must develop programming strategies to compete with these newer media, and in part, they must join in with the new distribution forms and be part of devising strategies to bring product to people in new ways.

Evaluating Programming

Part of a programmer’s job is evaluating programs and scheduling strategies. If a program is not obtaining an audience, is it because of inherent flaws within the program, or is it because the program is running at a bad time? What should a programmer do when a particular show or time period is not measuring up to expectations?

Historically, the most prevalent form of evaluation has been a body count in the form of TV audience measurement data from Nielsen and radio data from Arbitron. These companies, which operate independently from stations and networks, use sampling methodology to determine how many people are watching or listening to particular programs or dayparts. A series that does not score well in the Nielsen or Arbitron ratings will be scrutinized carefully.

The series, whether new or old, will be examined to see if it lacks focus. Sometimes producers of shows get wrapped up in new projects and don’t keep a close eye on previous shows, which then begin to drift off course. Internal bickering and story lines that are too convoluted can also lead to lack of focus. Sometimes all the programmer needs to do is sit down with the principals and discuss the problem openly so they can rectify it.

In a similar vein, there can be particular elements of a show, such as the demeanor of the lead actor, which are turning people off. Sending the show out for more testing often pinpoints the problem, and it can then be addressed. This is true not only for comedies and dramas but also for news shows where a particular anchor may be dragging down the show or for radio where the audience does not respond well to a certain disc jockey or talk show host.

Exhaustion is another reason that a series might fall in the ratings. Some series that have been on for many years simply run out of fresh ideas. Adding a new character (such as a grouchy uncle) to the series might help, as might bringing on some new writers. But sometimes a series has simply run its course, and it is time for programmers to let it bow out gracefully, as was done with many shows ranging from M*A*S*H to Sex and the City (Garner, 2002, pp. 38–43).

Yielding to exhaustion is particularly appropriate if the show is no longer in tune with social changes. The Brady Bunch, with its traditional family values and lightweight adventures appealed to audiences when it was launched in 1969. But during the 1970s, networks, in line with social changes, began programming grittier programs with more adult themes, such as All in the Family. Audiences lost their appetite for The Brady Bunch, and it was retired from network TV in 1974 (Garner, 2002, pp. 20–27).

Sometimes a show can have high ratings, but they are the wrong demographics—not the coveted 18 to 34 that advertisers prefer. This is likely to happen with a series that is on for a long time. The original audience members would have been the desirable demographic, but as they stick with the show they grow older and younger people are not attracted to the show. Sometimes, adding elements that will appeal to younger viewers helps. If not, a programmer needs to make a decision whether to cancel the series or whether to stay with it and try to attract advertisers who target the older demographic (Mares & Woodard, 2007).

A show can be aired in the wrong time period. Certainly, trying out a children’s show at midnight would not yield valid results, but airing a new, unknown series against a very popular series can lead to low ratings that have nothing to do with the content of the show. For example, Fox scheduled Family Guy on Thursday nights against Friends, where it understandably garnered abysmal ratings. Fox took the show off the air in 2000 and then put it back on Tuesday nights but coupled it with Greg the Bunny, and it did not do well. So Fox canceled it once again in 2002. It was the loyalty of its fans and its high DVD sales that made Fox reconsider, finally bring it back in 2005 and resting it peacefully before King of the Hill. Common sense would say that if a show is on at the wrong time period, a programmer should change the time period. However, that’s not always possible without damaging some other show or disrupting the entire schedule. It is not a good idea to relocate shows frequently because the audience loses track of them and only die-hard fans will make the effort to find them.

A new program may fail to gain an audience because it was not properly promoted and people are not aware of it. If the programmer feels that this is the case, the network or station can institute a strong promotion campaign (Walker & Eastman, 2000). However, if the real problem is something inherently wrong with the program, the promotion campaign will amount to nothing more than a costly expense that does no good.

Evaluation is an ongoing process. Although ratings are the most important factor, the awards (especially Emmys) that a show wins can figure into the evaluation process, as can faith in the show creator, feelings that the show is filling a useful social purpose, and other gut reactions of the programming team. In fact, gut reactions of programmers have been responsible for many successes on radio and TV. Good programmers keep an ear to the ground, an eye on the future, a shoulder to the wheel, a finger on the pulse of the public, and their feet on the ground. Dealing with all those contortions is one reason programmers turn over rather rapidly. But it is an exciting job and one that can have many visible positive ramifications.

Bibliography:

- Adams,W.J. (1993). TV programming scheduling strategies and their relationship to new program renewal rates and rating changes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 37, 465–474.

- Auletta, K. (1991). Three blind mice. New York: Random House.

- Avery, R. K., & Pepper, R. (1980).An institutional history of public broadcasting. Journal of Communication, 42, 126–138.

- Barnouw, E. (1996). A tower in Babel. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (2003). Controlling prime-time: Organizational concentration and network television programming strategies. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47, 573–596.

- Blumenthal, H. J., & Goodenough, O. R. (1991). The business of television. New York: Billboard Books.

- Eastman, S. T., & Ferguson, D.A. (2001). Broadcast/cable/web programming:Strategiesandpractices.Belmont,CA:Wadsworth. Garner, J. (2002). Stay tuned: Television’s unforgettable moments. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel.

- Goldenson, L. H. (1991). Beating the odds. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Goodwin, R. (1989). Remembering America. New York: Harper & Row.

- Hofmeister, S. (2003, April 22). Sale of Comedy Central stake sure is no laughing matter. Los Angeles Times, C-8.

- (1990). INTV census. Washington, DC: Association of Independent Television Stations.

- Keith, M. C. (2004). The radio station. Boston: Focal Press.

- Koch, J., Kosberg, R., & Norman, T. M. (2004). Pitching Hollywood: How to sell your TV and movie ideas. Sanger, CA: Quill Driver Books.

- Mares, M. L., & Woodard, E. H. (2007). In search of the older audience: Adult age differences in television viewing. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50, 595–614.

- Nielsen Company. (2007). Products. https://www.nielsen.com/au/en/news-center/products/

- Perebinossoff, P., Gross, B., & Gross, L. S. (2005). Programming for TV, radio, and the Internet. Boston: Focal Press.

- Peyser, T. (1979). Pat Weaver. Emmy, 1, 32–34.

- Shanks, B. (1976). The cool fire. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Shim, J. W., & Bryant, P. (2007). Effects of personality types on the use of television genre. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 51, 287–304.

- Sterling, C. H., & Kittross, J. M. (1990). Stay tuned: A concise history of American broadcasting. Belmont, CA:Wadsworth.

- Vane, E. T., & Gross, L. S. (1994). Programming for TV, radio, and cable. Boston: Focal Press.

- Walker, J. R., & Eastman, S. T. (2000). On-air promotion effectiveness for programs of different genres, familiarity, and audience demographics. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44, 618–637.

- Webster, J. G. (2006). Audience flow past and present: Television inheritance effects reconsidered. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50, 323–337.

- White, T. H. (2003). June 30, 1922 broadcast station list, 378 stations. In Commercial and government radio stations in the United States. Available at: https://earlyradiohistory.us/220630ca.htm