View sample leadership research paper on implicit leadership theories. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

When people meet a leader for the first time, they are not a blank slate. Rather, they have ideas as to what this person may be like and how he or she might behave. General ideas about what leaders are like and how they behave are called implicit leadership theories (ILTs). This term was introduced in 1975 by Eden and Leviatan. Although for a long time, leadership research and practice focused on actual leaders’ traits and behaviors, the existence of implicit leadership theories is now widely acknowledged. This theory draws attention to the role of the follower in the process of leadership. Leadership is not only what a leader does but also what a follower makes of it. Research has focused on the contents of implicit leadership theories and their effects. In this research-paper, after briefly introducing the most prominent concepts associated with the theories, the focus is on the latter, namely, an outline of how prior research may influence management decisions.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Theory I: Implicit Leadership Theories

Implicit leadership theories comprise ideas about leaders in general, and these are independent of what an actual leader is like or how one views one’s own leadership. Implicit leadership theories are about images of leaders in general. What comes to your mind when you think of the term leader? Most of us are quite able to describe a person labeled as leader without ever having met this person. This is because we have a strong idea of what characteristics certain groups of people possess as part of their group membership. To offer another example, you may have specific ideas about a typical football manager, a politician, a teacher, or a pilot. Think about typical clothes they wear, what they look like, and how they will probably behave. Moreover, you will have some ideas about their traits and attitudes. These attributes that are associated with any member of a particular group are called schemata and stereotypes. They may or may not be true. The most important thing is that these schemata guide our perceptions of others, and we use them automatically in our judgment of a person we hardly know. Recall that many people articulated serious concerns about whether a fair-haired actor like Daniel Craig could adequately fill the role of James Bond that had been shaped by Sean Connery. Long before the movie was out, there was a discussion in the media if this man is tough enough. Obviously, in many people’s minds there exists a clear implicit theory of the characteristics of a royal spy. As in everyday life, only with more knowledge of a person, we can overcome our stereotypes. So, remember, the actual person you meet who is a leader may or may not correspond to your image of leaders in general. We can easily imagine that it makes a difference for our acceptance and our behavior toward a leader if we recognize him or her as a leader or not.

So far, research into implicit leadership theories mostly refers to ideas about effective leaders. However, in public there are also quite negative images of leaders. Think of the cartoon character Dilbert to understand the idea. The image conveyed here is that bosses are generally incompetent.

Although implicit leadership theories of effective leaders may differ between persons, some aspects seem to be culturally shared. Using questionnaires, a large project called Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE; see, e.g., House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004), found that charisma is a characteristic that most people in different cultures think of when they think of an effective leader. Note, however, that qualitative interview studies showed some cultural difference with respect to the ideas people have of effective leaders (cf. Ling, Chia, & Fang, 2000; Offermann, Kenedy, & Wirtz, 1994).

Another interesting phenomenon in the line of implicit leadership theories is the tendency we all have to attribute company performance to leaders. This is what James Meindl (1990) introduced as the Romance of Leadership. Just think of your favorite sport team and what happens when they lose. Very often, in the case of failure the blame is put on the coach. Just as when the opposite happens, the coach is praised as a local or even national hero. This, however, ignores other influencing factors (in companies as well as in sport teams), such as the economic situation, legal constrains, and so forth. The most important concepts that are related to implicit leadership theories are briefly outlined in the following sections.

Social Construction and Information Processing

Given the fact that leadership is shaped by the followers, the question must be raised as to what are the underlying psychological and social mechanisms. To give an example, you may imagine that you have been appointed to be a member of a project team that has to accomplish a difficult task in your company. You have met neither the other members nor the leader of the group. When entering the conference room where the kickoff meeting is going to start, you find people still standing around and talking to each other. As you do not know anyone in the room, you may need some orientation. One source you expect to get some orientation from is the leader of the group. Therefore, you are looking around to identify this person. Our implicit leadership theories that consist of structures in our mind or memory contain typical traits and behaviors of leaders (Eden & Leviathan, 1975). These cognitive structures or schemata are always made salient when we are confronted with leaders or situations where leadership plays an important role (Lord, de Vader, & Alliger, 1986). These cognitive structures consist of categorization systems that help to distinguish between leaders and nonleaders in a specific situation. According to this system, a typical leader may be older than you are, male, and wearing more formal clothes like a jacket and a tie. Moreover, a leader will not stand alone. Instead, a leader is expected to be with others and talk to them, while the others are expected to listen. These attributes may characterize a typical leader in a specific situation. The image of a typical leader is like a prototype. Prototypes of leadership are a key concept for categorization. If someone in the scene mentioned previously matches our categories or cognitive schemata of leader prototypes, this person will be recognized as a leader, whether or not, of course, he or she is the leader (Lord, Foti, & de Vader, 1984). Categorization and recognition are two important steps in our information processing. If this person in the situation mentioned previously speaks, goes to the front desk, and so on, we would pay attention, sit down, and listen to what he or she has to say. Probably we are ready to accept and support this person because he or she is the leader in this situation. In doing so we start to behave like followers and help with the social construction of leadership. Now, imagine that a quite different type of person opens the meeting. Probably you will be astonished that this young guy was assigned to be the project leader. As a consequence, you might hesitate to attribute competence and remain skeptical of his abilities. It is important to be aware of the fact that it might be hard for the leader to initially gain confidence and authority if most members share similar expectations toward a leader that are not met in the particular case. Instead of the leader being enabled, we would not be surprised if he failed.

Another setting that makes the idea of the social construction of leadership even more evident is a group without a formal leader. After a short period, a leader will emerge. Research has shown that those who meet leadership categories in general and represent the prototype of the group will become leaders by receiving reinforcement and support. Their influence is accepted, though there was no formal assignment or any kind of election.

What are the characteristics that typically match leadership prototypes? From research on the emergence of leadership, there is considerable evidence that potential leaders’ characteristics such as sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength are associated with effective leadership (Offermann et al., 1994). Therefore, a group looking for someone to fill the leadership position will probably choose the person that best represents these categories. However, we have to keep in mind that the characteristics that make a successful leader in the minds of others may be different in different cultures. This is underlined in a Chinese study (Ling at al,. 2000) which found that their Chinese participants named characteristics such as personal morality, goal effectiveness, interpersonal competency, and versatility as important for effective leadership. That means that implicit leadership theories not only differ between persons, but are also influenced by culture. We will come back to this point later in this research-paper.

Social Identity Theory

For a more differentiated perspective, the social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986) proposes that to some extent the schemata and categories that differentiate leaders from nonleaders are not static. Social identity theory proposes that they will be continually rebuilt as new information is available or as the task and context change (Hogg, 2001; Lord, Brown, Harvey, & Hall, 2001; Lord & Emrich, 2000). Studies conducted within the frame of social identity theory were able to show that the emergence of a leader is based on her or his “prototypicality” for the characteristics of a group in a specific situation (Haslam & Platow, 2001; Nye, 2002). To give an easy example, one can imagine the same group of persons from the previous example without a formal leader in quite different situations. One situation is in the work context where the group has to plan a marketing strategy for the introduction of a new product. The other situation is on a hiking tour in the mountains after the group has lost their way and it is getting dark. In the first situation qualities like specific market knowledge, social skills, ambiguity tolerance, and creativity are crucial for the success of the group; therefore, the person who has the best match with this profile probably will emerge as the leader. In the second situation, someone else will probably get into the leading position. The group will look for the member who best represents physical strength, fitness, wilderness and outdoor experience, and emotional stability.

Culture and Implicit Leadership Theories

It is argued that people within one culture share a common set of categories that characterize a prototypical leader (House et al., 2004; Lord, 1985; Shamir, 1992). According to Offermann et al. (1994), we can assume that sensitivity, dedication, tyranny, charisma, attractiveness, masculinity, intelligence, and strength are associated with effective leadership in the United States; according to Ling et al. (2000) personal morality, goal effectiveness, interpersonal competency, and versatility are important for effective leadership in China.

However, results from the GLOBE study show that beyond individual and situational variability, there appear to be universal elements of implicit leadership theories. The GLOBE project assessed implicit leadership theories in 62 different countries (House et al., 2004). They asked 17,370 managers from 951 organizations to indicate for different characteristics how far they contribute to a person being an outstanding leader or inhibit a person from being an outstanding leader. The image of an ideal leader in a specific culture is based on the culturally endorsed leadership theory (CLT). On the basis of 62 countries, 10 regional clusters with common language, history, and religion were formed—for example, Anglo (United States, United Kingdom, Canada), Germanic Europe (Germany, Netherlands, Austria), Latin Europe (France, Italy, Spain), Eastern Europe (Greek, Russia, Poland), Confucian Asia (China, Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan), and Southern Asia (India, Indonesia, Thailand).

Overall, six dimensions of culturally endorsed leadership theory were identified: (a) charismatic/value-based, (b) team oriented, (c) participative, (d) humane oriented, (e) autonomous, and (f) self-protective. The results indicated that charismatic or value-based leadership and team-oriented leadership are prominent dimensions of effective leadership theories worldwide. Participative and humane-oriented leadership are also endorsed in many countries, whereas autonomous and self-protective leadership were considered as neutral or even negative for effective leadership. The comparison of country clusters reveals, for example, that in countries from the Germanic Europe cluster, participative leadership is highly appreciated, whereas in countries from the Confucian and Southern Asia clusters, participative leadership is less emphasized. A reversed pattern shows up for self-protective leadership. This kind of leadership is highly endorsed in Asian countries and less appreciated in the Germanic Europe cluster (House et al., 1999; House et al., 2004).

Self-Concept

So far, we have argued that, to some extent, leadership categories are universal, and to some extent, they are only valid within one culture. We also pointed out that the context and the task influence which categories will be salient. Current studies in the area of self-concept research have added one more factor that explains which categories are preferred. According to Keller (1999), followers’ self-concepts are related to the idea of the characteristics of an ideal leader. She found that the ideal leader is construed as similar to the self. Imagine a person who is extroverted, prone to risk taking, and very communicative. For such a person, an ideal leader should be at least as tough. For followers who do not share these characteristics, this kind of leader would be overdemanding and therefore not representative of their idea of an effective leader. Romance of leadership as an implicit leadership theory is also influenced by followers’ personalities. Persons who rate themselves as similar to leaders in general on specific traits (e.g., extraversion) are more prone to romanticize leadership. This concept is described in the next paragraph.

Romance of Leadership

Besides categorization, attribution plays a crucial role in implicit leadership theories. This means that we have assumptions of what can result from leadership in terms of consequences. On the other hand, we have an idea of what event probably has been caused by leadership and not by any other reason. Accordingly, not only do people ascribe leaders certain characteristics, they also assume a relationship between success and leadership (Meindl, Ehrlich, & Dukerich, 1985). That means that if a company is successful, its leaders are often considered the origin of this success. Factors outside the control of leaders such as the general economic situation or legal issues are usually ignored or thought to be less important compared to leadership. We might say that leaders are considered almighty.

The process we just described has also been called the social construction of leadership. Although in many cases we do not know about the actual influence of a leader, we just assume he or she is responsible for the company’s performance. This is what Meindl (1990) called romance of leadership. Our image of leaders in general tends to be rosy, and we ascribe them more influence than they actually have (remember the sport teams). Interestingly, this effect is quite common. Especially in times of extraordinarily good or bad company performance, the focus is on the leader. Meindl and colleagues (1985) confirmed this in business journals as well as in dissertation topics.

Romance of leadership can also be understood from an information-processing perspective. It helps people to structure and to make sense of organizational phenomena that are complex, ambiguous, and difficult to understand (Meindl et al., 1985; Shamir, 1992). Leadership serves as a plausible category for a better understanding and a sense of control with regard to failure and success in organizations. This tendency may be reinforced by the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977), which implies that people in general tend to focus on the role of personal causes and underestimate situational factors. The need of followers to understand and make sense of things is particularly high in cases of unexpected success or failure.

Theory II: Effects Of Implicit Leadership Theories In Organizations

Knowing that we all have implicit leadership theories in mind leads to the question of what effects these implicit leadership theories have. In the following section, we will summarize a few that have been mentioned in prior research. The effects of implicit leadership theories in organizations comprise effects on the perception of actual leaders, on the satisfaction and performance of followers, and on leaders’ careers.

Perception of Leadership

With respect to the effects of implicit leadership theories on the perception of leadership, research has mainly focused on the perception of charisma. The reason for this is simple: We all know charisma when we see it, but it is difficult to describe. So, one could argue that charisma is open to projection. This means that regarding a leader as charismatic could be dependent on the observer as well as the leader.

Effects of Implicit Leadership Theories

- Perception

- Satisfaction

- Performance

- Careers

- Decision making

Recently, Schyns, Felfe, and Blank (in press) conducted several studies and a meta-analysis (that is a quantitative review of prior research) on the relationship between romance of leadership and the perception of charisma. They indeed found that romance of leadership is related to the perception of charisma, meaning that across several studies with different contexts, conducted in different countries, how charismatic a leader was regarded depended on the strength of one’s tendency to view leaders in a romantic way.

Satisfaction And Performance

Another line of research has focused on the effects of a match between followers’ implicit leadership theories and leaders’ behavior. So, now we are not talking about how the perception of a leader is shaped by our implicit leadership theories, but in how far the degree of match between our implicit leadership theories and the traits and behaviors of a real leader affects how much we like this leader. Nye (2005; Nye & Forsyth, 1991) has undertaken experimental research showing that a mismatch between followers’ implicit leadership theories and leaders’ behavior has negative effects on followers’ rating of that leader with respect to good leadership and with respect to performance. Nye’s (2005) experiment was conducted as follows. She first asked students to indicate (using ratings on several characteristics) what characteristics a student with good leadership qualities would have. The participants then executed a task under the leadership of a colleague of the researcher. Subsequently, they were asked to indicate their perception of this leader. It turned out that those leaders who matched the implicit leadership theories of the participants were evaluated better than those who did not match their implicit leadership theories. That means that when an actual leader does not act the way we expect a leader to behave, our estimation for this leader goes down. This has very important consequences for leaders themselves as is outlined later in the research-paper.

Figure 1 ILT and the Perception of Leadership

Performance Evaluation and Gender/Culture

In order to find out more about the effects of implicit leadership theories on the evaluation of leaders, we can look into research on gender and leadership. Heilman (1983, 2001) introduced the “lack of fit” idea, referring to the assumption that stereotypes of women and stereotypes of leaders (or implicit leadership theories) are incongruent. That means women can behave like women, in which case they are believed not to be suitable as leaders, or they can behave like leaders, in which case they violate gender stereotypes. Both processes lead to a devaluation of female leaders. Similarly, Schein’s (1973, 1975) approach, the “think-manager-think-male” phenomenon, refers to the fact that when people think of managers, they think of men rather than women, and that for most people, leadership characteristics are male rather than female. In essence, when implicit leadership theories do not fit the female stereotype, this can and does lead to lower performance evaluations and, in the end, lower promotion chances for women than for men.

Implicit leadership theories also have an effect on the evaluation of leaders across cultures. Although some characteristics of successful leadership seem to be spanning across cultures, other evidence suggests that there are some differences among cultures with respect to the ideas people have about what makes a successful leader. This is important for leaders who work in different cultures or who move from one culture to another. As we have seen, the match between implicit leadership theories and actual leader behavior influences followers’ evaluations of their leaders. This means that a leader can be highly valued in one country but considered unacceptable in another.

Performance Evaluation in General

What we have said so far about the effects of implicit leadership theories for performance evaluation and careers of leaders, leads us to explain some general effects of expectations on the rater and the rated person.

First, there is an effect that we call the Pygmalion effect. This name goes back to Greek mythology. The Greek sculptor Pygmalion carved a sculpture, Galatea, and fell in love with her. The goddess Venus took pity with him and turned Galatea into a real woman. Nowadays, the Pygmalion effect refers to situations in which an evaluator treats a person in a way that makes his or her assumption about this person come true. Rosenthal and Jacobson (1968) first reported this effect in classrooms where teachers gave students, of whom they thought highly, a greater chance to contribute to the lesson. Similarly, we can assume that if someone thinks highly of a person (i.e., ascribes this person leaders’ characteristics) he or she may give this person more opportunities to contribute to the organization and, ultimately, reach a promotion. Of course, the opposite is true as well. If people are not perceived as leaders, they may be given less opportunities to prove themselves.

The astonishing thing is that stereotypes or ideas others have of us influence our own behavior. That means that not only are we treated differently depending on the images of others, but also our own behavior may change as well. This is due to an effect we call “stereotype threat” (Spencer, Steele, & Quinn, 1999). Going back to the gender example, this means that women whose experience is that others believe they do not have leaders’ characteristics, may, in the end, not show these characteristics. They fulfill the prophecy themselves. Imagine a woman who is assigned to a leading position in a department of a bank. Her new boss is very friendly and warm when meeting her for the first time promising any kind of support she requires. He also tells her, however, that it might be difficult for her as a woman to run that department successfully, because the communication among the men is often relatively rough, and he has doubts if they can behave like gentlemen. Imagine that you were in her place. How encouraging is this message, and how would you communicate with your team when starting your job? Furthermore, what can we expect if any problems occur in the team?

Career

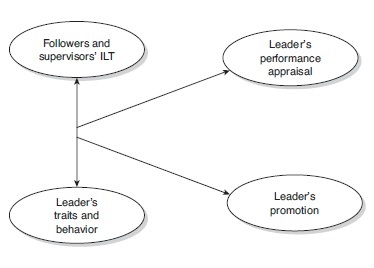

On a more general level, Schyns (2006b) suggested that implicit leadership theories not only affect the evaluation of female leaders but also those of leaders in general when they do not fit the prevalent implicit leadership theories in their organization. More importantly, she suggested that besides the immediate evaluation of leaders, their promotion chances might suffer if they do not fit their followers’ or supervisors’ implicit leadership theories. Remember Nye’s research cited previously. Here, followers rated leaders lower when they did not fit their implicit leadership theories. When decisions about promotions of leaders are made and follower ratings are taken into account, leaders who do not fit will have lower chances of promotion (see Figure 2). Similarly, supervisors hold implicit leadership theories and may give leaders who do not fit their implicit leadership theories lower promotion chances.

Decision Making

How far do implicit leadership theories not only influence followers’ perceptions and judgments but also guide managers’ decisions? As pointed out previously, a perceived misfit between implicit leadership theory and leader behavior may influence managers’ decisions in a way that negative consequences for low-level leaders’ career development can be expected. Felfe and Petersen (2007) extended this approach, as they claimed not only that followers’ perceptions and attribution of leadership are determined by implicit leadership theories, but also that the behavior of top managers, CEOs, executive board members, and other stakeholders is influenced by their respective implicit theories of leadership. In particular, they postulated that romance of leadership will influence top leaders’ behavior in terms of decision making. In their decisions, they assign responsibilities, tasks, and resources to a specific leader. These decisions are supposedly influenced by the degree to which a leader meets their expectations and how important the role of leadership is considered in general. According to the romance of leadership theory, Felfe and Petersen argued that persons who believe that a leader’s capability is the core factor for success or failure, as proposed in the theory, will tend to base their decision for an enterprise or a project on the evaluation of the leader rather than on alternative factors. Whereas the influence of other factors is de-emphasized, the influence of leadership is overemphasized.

Figure 2 ILT Match and Evaluation and Promotion

Think about the following situation as the participants in the study were asked to do. Imagine you are a member of the executive board of a midsize, prosperous pharmaceutical company and you are preparing for tomorrow’s board meeting. There are a lot of decisions on tomorrow’s agenda and you have some project proposals that are going to be discussed and decided. One project, “Vectra C+” for example, is on developing a new medicine for the European market. Experts say that for reasons of demographic development, an increased demand can be expected. Moreover, there will be political and financial support from the local government. To sum up, the prospects of success for Vectra C+ in the given situation are relatively high. However, the leader designated for this project, Mr. Cohen, is not very experienced. His performance appraisals only reached average level in the past, and some subordinates have complained about his leadership style. You will probably find it difficult to decide whether you would approve or would not approve this project, because on the one hand, the situation seems to be very favorable, but on the other hand, the probability of success of the leader designated seems to be limited. Before deciding, you may want to have a look at another project proposal. The project “Triple A” is building a new factory in an African country. This means costs for transportation and production will decrease significantly.

However, some experts have articulated some concerns. Corruption can be anticipated, and the recruitment of a qualified workforce will be difficult. Moreover, analysts say that there is severe competition in this specific market. The leader designated for this job is Mr. Bem, who is an experienced project manager. He is a convincing personality, followers are enthusiastic about his management style, and he has considerable diplomatic capabilities to deal with local authorities. In the past, he has made nearly every project a success. How would you decide on this project? Which of the projects would you prefer?

In Felfe and Petersen’s (2007) study, participants were presented a set of short descriptions of proposed projects such as Triple A and Vectra C+ mentioned previously. They were asked to make a decision for each of them on the basis of the information provided. As you might have already guessed, two factors have been systematically varied: the probability of the success of the leader and the probability of the success of the situational context. Their results clearly showed that the approval of a project was higher when the leader’s probability of success was high and the situation was more unfavorable (as in Triple A) than in situations where the leader’s probability of success was low but the situation was favorable as in project Vectra C+. The fact that participants relied more on the leader’s probability of success corresponded with their individual assessment of romance of leadership. In general, participants in the study who scored high on romance of leadership approved projects to a greater extent if the leader’s probability of success was high, and approved projects to a lower extent if the leader’s probability of success was low.

Although participants’ decisions are based on both sources of information—the leader and the situational context—the findings provide evidence that the information about the leader is more influential than the information about the context. These results support the romance of leadership theory, which proposes that the role of the leader is overemphasized and circumstances are neglected.

Application: Challenges For Management

When regarding the previously cited results of the effect of implicit leadership theories, we can see that these are serious and, therefore, implicit leadership theories need to be taken into account by managers. In an organization, different issues arise from the knowledge of implicit leadership theories. Some of these are sketched out later in the research-paper.

360-Degree Feedback

Knowing the effect of implicit leadership theories on the perception of actual leaders challenges 360-degree feedback in several ways. First, feedback based on the average of follower ratings may not be accurate. When follower (and supervisor) ratings are influenced by implicit leadership theories, their ratings cannot be taken at face value. Rather, it is important to find out about the effects implicit leadership theories have had on those ratings in order to be able to give fair and accurate feedback to leaders.

Second, the variance in follower ratings is meaningful. This means that when followers view the same leader differently, this can serve as an important piece of information on how to motivate and stimulate individual followers based on their implicit leadership theories.

Enhancing Satisfaction and Performance

As outlined previously, a mismatch between followers’ implicit leadership theories and leaders’ behavior can have serious consequences for followers’ satisfaction and performance. The task of management is to prevent the negative effects of a mismatch. One way of doing so is careful placement and training. Especially, in intercultural leadership, making the leader aware of different expectations can enhance the interaction between leaders and followers and overcome the negative effects of a mismatch.

Another strategy may be to make implicit theories explicit and examine their influence on communication and cooperation in organizations. Survey feedback or team development processes enable leaders and followers to reflect and communicate upon their respective theories on leadership and followership. In doing so, mutual expectations can be articulated. Points of agreement and discrepancies become obvious and can be clarified. Unrealistic follower expectations of their leader can be corrected, and misunderstandings can be solved. Leadership guidelines and executive training may also help to facilitate overt communication between leaders and followers.

Fairness in Promotion Decisions

Assuming that, because they do not match their supervisors’ or their followers’ implicit leadership theories, leaders may not be promoted to higher positions has risks for fairness in promotion decisions. Promotion decisions should be generally based on performance, not on biases toward certain traits and behaviors. Fairness and putting the right person in the right place are crucial in organizations which may otherwise lose important resources and experience diminished success. Again, it is important to make decision makers aware of the possible influence of implicit leadership theories on promotion decisions. A more standardized procedure in selection and promotion decisions can also help to improve the decision-making process. If less room for individual interpretation is left in these decisions, they are less vulnerable for biases.

Making the Right Decisions

In general, there is no doubt that decisions may be less effective when situational information is neglected and only the information on a leader is considered relevant since there is a high risk that organizations overlook important chances or underestimate risks. Considering the effects of romance of leadership on decision making, it is important that decision makers in organizations are aware of this general tendency and their individual implicit leadership theory in order to avoid serious flaws when making decisions. It is possible that a company may lose future market opportunities. Persons are more likely to reject a promising project if the leader does not meet expectations. In other cases, direct damage and financial loss for the organization may occur when risks are underestimated. Even when provided with many strong arguments for the rejection of a project, people seem to believe that there will still be a considerable chance for the project if only a competent leader is in charge. It is doubtful that an implicit leadership theory that overemphasizes the importance of the leader is appropriate for complex managerial settings. Therefore, managers in organizations should be advised not to neglect important information about the context and thereby engage in questionable projects. Accordingly, Felfe and Petersen (2007) argued that coaching, training, and case studies should be used as methods for managers and executives to reflect on their implicit theories and improve their decision making.

Avoiding Cultural Misunderstandings

Given that implicit leadership theories are different in different cultures, the effect and reactions leaders will evoke in different cultures may not be comparable. This means that leaders’ success may not be transferable between cultures. Leaders should be aware of the different expectations and different effects they have in different cultures. Intercultural training or so-called cultural intelligence (Earley & Ang, 2003) can help overcome problems of a mismatch between a leader and the implicit leadership theories of his or her followers.

Future Directions

In terms of the development of implicit leadership theories, we know that implicit leadership theories develop early in life (Ayman-Nolley & Ayman, 2005). Already young children can draw leaders and develop individual differences in their images of leaders. Also, research has shown that implicit leadership theories are related to personality (Felfe, 2005). In particular, self-esteem is related to romance of leadership, that is, the tendency to (over-) attribute responsibility for company performance to leaders. However, although there seem to be some stable factors involved in explaining why implicit leadership theories differ for individuals, little is known yet about possible changes and developments of implicit leadership theories. Epitropaki and Martin (2004) found that implicit leadership theories are stable in times of leader change. As they also found differences between types of organizations, we may assume that socialization plays a role in the development of implicit leadership theories. More research is needed on issues such as which crucially affects implicit leadership theories have or how much time implicit leadership theories need to change, for example, in case of a change of profession.

As mentioned before, implicit leadership theories are not independent of culture. In the future, given increasing globalization, this point will receive growing importance. As more and more managers work in different cultures, their awareness of the different implicit leadership theories they may be confronted with can become a crucial indicator of the success or failure of international as-signments or cross-cultural leadership. Obviously, this point will not only be more important when cultures that differ significantly are involved (e.g., the United States and China), but also when similar cultures are involved (e.g., the United States and the United Kingdom); differences in implicit leadership theories should not be underestimated.

Summary

In summary, we can say that implicit leadership theories play an important role in organizational processes even if more research is needed. We have seen that the perception of an actual leader and his or her evaluation may be influenced by implicit leadership theories. In addition, decision making is not free of bias. For organizations, it is therefore crucial to learn about the effects of implicit leadership theories and also to learn how to avoid them.

Bibliography:

- Ayman-Nolley, S., & Ayman, R. (2005). Children’s implicit theories of leadership. In B. Schyns & J. R. Meindl (Eds.), The leadership horizon series: Implicit leadership theories—Essays and explorations (Vol. 3, pp. 227-274). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Earley, P. C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership theory as a determinant of the factor structure underlying supervisory behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 736-741.

- Endrissat, N., Miiller, W. R., & Meissner, J. (2005). What is the meaning of leadership? A guided tour through a Swiss-German leadership landscape. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Conference, Honululu, Hawaii.

- Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2004). Implicit leadership theories in applied settings: Factor structure, generalizability, and stability over time. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 293-310.

- Felfe, J. (2005). Personality and romance of leadership. In B. Schyns & J. R. Meindl (Eds.), Implicit leadership theories: Essays and explorations (pp. 199-225). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Felfe, J., & Petersen, L. -E. (2007). Romance of leadership and management decision making. European Journal of Work-and Organizational Psychology, 16, 1-24.

- Haslam, S. A., & Platow, M. J. (2001). The link between leadership and followership: How affirming social identity translates vision into action. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1469-1479.

- Heilman, M. E. (1983). Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. In B. Straw & L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 5, pp. 269-298). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 657-674.

- Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 184-200.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA:Sage.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Dickson, M., et al. (1999). Cultural influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE. In W. H. Mobley (Ed.), Advances in global leadership (Vol. 1, pp. 171-233). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

- Keller, T. (1999). Images of the familiar: Individual differences and implicit leadership theories. Leadership Quarterly, 10,589-607.

- Ling, W., Chia, R. C., & Fang, L. (2000). Chinese implicit leadership theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 140,729-739.

- Lord, R. G. (1985). An information processing approach to social perceptions, leadership and behavioral measurement in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7,87-128.

- Lord, R. G., Brown, D. J., Harvey, J. L., & Hall, R. J. (2001).Contextual constraints on prototype generation and their multilevel consequences for leadership perceptions. Leadership Quarterly, 12, 311-338.

- Lord, R. G., de Vader, C. L., & Alliger, G. M. (1986). A meta-analysis of the relation between personality traits and leadership perceptions: An application of validity generalization procedures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71,402-410.

- Lord, R. G., & Emrich, C. G. (2000). Thinking outside the box by looking inside the box: Extending the cognitive revolution in leadership research. Leadership Quarterly, 11, 551-579.

- Lord, R. G., Foti, R. J., & de Vader, C. L. (1984). A test of leadership categorization theory: Internal structure, information processing, and leadership perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34, 343-378.

- Meindl, J. R. (1990). On leadership: An alternative to the conventional wisdom. Research in Organizational Behavior, 12, 159-203.

- Meindl, J. R. (1998). Appendix: Measures and assessments for the romance of leadership approach. In F. Dansereau & F. J. Yammarino (Eds.), Leadership: The multiple-level approaches—Part B: Contemporary and alternative (pp. 199302). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

- Meindl, J. R., Ehrlich, S. B., & Dukerich, J. M. (1985). The romance of leadership. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30,78-102.

- Nye, J. L. (2002). The eye of the follower—Information processing effects on attribution regarding leaders of small groups. Small Group Research, 33, 337-360.

- Nye, J. L. (2005). Implicit theories and leadership perceptions in the thick of it: The effects of prototype matching, group setbacks, and group outcomes. In B. Schyns & J. R. Meindl (Eds.), The leadership horizon series (Vol. 3). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Nye, J. L., & Forsyth, D. R. (1991). The effects of prototype-based biases on leadership appraisals: A test of leadership categorization theory. Small Group Research, 22, 360-375.

- Offermann, L. R., Kennedy, J. K., & Wirtz, P. W. (1994). Implicit leadership theories: Content, structure, and generalizability. Leadership Quarterly, 5, 43-58.

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom: Teacher expectation and pupils’ intellectual development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 173-220). New York: Academic Press

- Schein, V. E. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 95-100.

- Schein, V. E. (1975). Relationships between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(3), 340-344.

- Schyns, B. (2006a). Implicit theory of leadership. In S. G. Rogelberg (Ed.), The encyclopedia of industrial and organizational psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Schyns, B. (2006b). The role of implicit leadership theories in the performance appraisals and promotion recommendations of leaders. Equal Opportunities International, 25, 188-199.

- Schyns, B., Felfe, J., & Blank, H. (in press). Is charisma hyper-romanticism? Empirical evidence from new data and a meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: An International Review.

- Schyns, B., & Meindl, J. R. (2005). Implicit leadership theories: Essays and explorations. In The leadership horizon series (Vol. 3). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

- Shamir, B. (1992). Attribution of influence and charisma to the leader: The Romance of Leadership revisited. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 386-407.

- Spencer, S., Steele, C. M., & Quinn, D. M. (1999). Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 4-28.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In W. G. Austin (Ed.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago: Nelsen Hall.