View sample journalism research paper on story development and editing. Browse journalism research paper topics for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Telling a good story is the heart and soul of journalism; however, you can’t tell a good story without doing a good job of reporting—gathering information to share with your audience. Identifying important and interesting issues, events, and people to report about is a critical part of the reporting process. In addition, carefully editing the semifinished product to ensure that it fits the allotted time or space and to ensure accuracy, plus to check for proper grammar, spelling, punctuation, and style, is necessary to increase the chances that audience members will find the story interesting, informative, entertaining, and thought provoking.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Story Selection

Selecting interesting and/or important aspects of life to report about would seem to be a relatively easy thing to do, but declining readership, listenership, and viewership for many of the traditional news media clearly contradicts that assumption. The key to identifying and developing compelling news stories is always to keep in mind what’s likely to be relevant to audience members (Brooks, Kennedy, Moen, & Ranly, 2008, p. 4; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 31–39). What people, places, things, and issues are audience members interested in, and what do they care about the most? Perhaps a time-honored prescription about what is good journalism sums it up best: “Make the important story interesting and the interesting story important.”

Years of practice and research in journalism have identified a number of factors that play a part in the process of achieving that critical goal. Among these are the “uses and gratifications” that people associate with news media messages; the news values/ elements/qualities used by journalists to help them select which issues, events, and people to report about; and the traditional five Ws and the H—who, what, where, when, why, and how.

Uses and Gratifications

People have told researchers that they become news consumers for a variety of interesting reasons. They have a number of “uses” for the information they obtain, and they obtain a number of “gratifications” from consuming such information (Levy, 1978; Levy & Windahl, 1984; Vishwanath, 2008). By knowing about and understanding such uses and gratifications, reporters can begin to build a framework for their information-gathering mission. Among the major uses and gratifications are surveillance, reassurance, intellectual stimulation, emotional fulfillment, and diversion.

Surveillance deals with simply keeping up with what’s happening in your town, city, state, region, country, and world. Reporters who can find interesting information about the important happenings of each day will be successful.

Reassurance deals with information that helps people feel better about themselves, the decisions they make, and their lives in general. Examples include providing the views of experts, providing good examples and bad examples, providing how-to advice for helping deal with the common problems in life, plus including information about alternatives that might make life better.

Intellectual stimulation deals with information that causes people to think and provides them with opportunities to compare their views with those of others. Getting experts, celebrities, and even lay people to illuminate, praise, criticize, explain, analyze, synthesize, and speculate often can provide such information.

Emotional fulfillment deals with information that helps people relax, smile, cry, feel good or bad about something, and feel some empathy. Delving into historical or backstory-type elements, how people cope with problems, achievement-related statistics, and acts of courage/heroism often can provide such information.

Diversion deals with information that helps people forget about their problems (at least for a little while), reduce stress, and decompress after a tough day. Searching for humorous anecdotes, off-beat developments, unusual outlooks, and strange incidents often can provide such information.

News Values/Elements/Qualities

News values/elements/qualities include significance, prominence, proximity, timeliness, conflict, oddity, achievement, sex/romance (Brooks et al., 2008, p. 6; Campbell, 2004, pp. 104–125; Reese & Ballinger, 2001). Significance deals with how many people will be affected and how deeply they will be affected. An adage holds that the greater the scope of the impact, the greater the chances that events and issues will become news. Prominence deals with the status and/or notoriety of the people involved in an event or issue. The more well-known a person is, the more likely it is that whatever he or she does will be judged newsworthy. Proximity deals with the “localness” of the events and issues. The nearer events and issues occur to the target audience, the more likely it is that the events and issues will become news. Timeliness deals with how recent events and issues are. The more recent the events and issues, the more likely they will become news. If conflict exists in connection with events and issues, it’s more likely they’ll become news. The more unusual, out of the ordinary, strange, and off-beat events and issues are, the more likely they’ll become news. If events and issues feature elements of setting records and establishing standards of excellence, the more likely they’ll become news. If events and issues contain elements of sex, romance, and affairs of the heart, the more likely they’ll become news. In addition, if events and issues feature emotional aspects that tug at the heartstrings, have humorous or at least amusing aspects, serve as examples of good things to do or bad things to do, include acts of heroism or selflessness, or have an animal associated with them, the more likely they’ll become news.

The Five Ws and the H

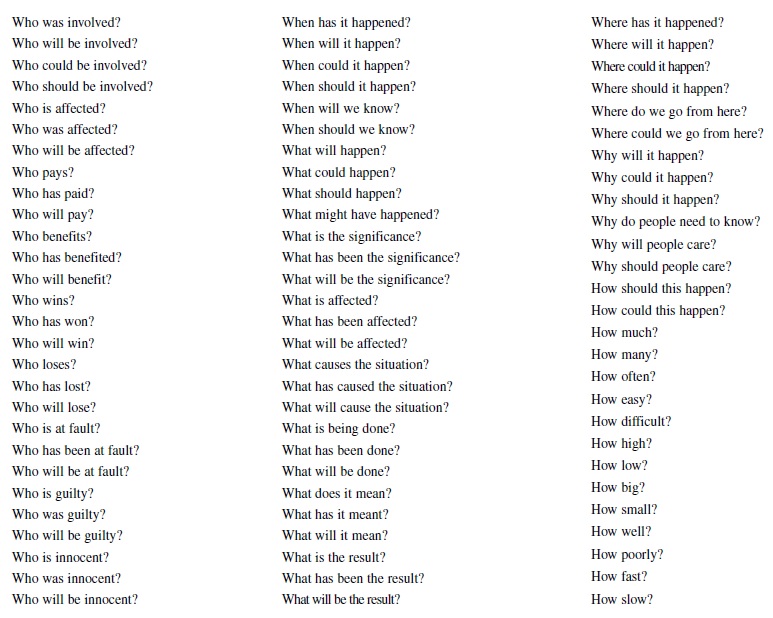

The five Ws and the H provide more scaffolding for the process of selecting what issues and events will become news (Gibbs & Warhover, 2002, pp. 102–117; Hansen & Paul, 2004, p. 55). Who is involved, what’s going on, where it’s all happening, when it’s happening, why it’s happening, and how it’s happening normally are important considerations in the news decision-making process. The five Ws and the H are important parts of the reporting process, too, of course, but they often are used in an effort to select the events and issues that will be reported about.

Generating Story Ideas

Ideas for stories can come from a variety of sources (Harrower, 2007, pp. 66–77; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 37–39; Quinn & Lamble, 2008, pp. 15–28). The life experiences of journalists, their family members, friends, neighbors, associates, acquaintances, colleagues, advertisers, and audience members are typical sources. The joys and heartaches of everyday life, coping strategies, successes, and failures can all be fertile ground for story idea generation.

Other traditional sources for story ideas include localizing regional, state, national, and international events and issues; following up on stories done by competing news organizations; and investigating the issues associated with breaking-news events. If something interesting happens miles away in another town, city, state, or country, is there a local angle that can be explored? Were local people, companies, agencies, or departments involved in any way? If so, the local angle might be developed into a local story. Even if no locals are involved, perhaps a check with local officials, companies, and experts to find out if something similar has ever happened locally, or perhaps could happen locally, might lead to a good local story.

If a news organization reports a story one day, it’s not uncommon to see follow-up stories on subsequent days by competing news organizations. Different angles and elements typically are reported about in such stories, and different sources of information are consulted.

A variation of the follow-up story is an examination of the issues associated with a breaking-news event. For example, after reporting about a major traffic accident at a local intersection, a series of stories might be done that examine ways to improve traffic safety, that explore techniques that help increase survival chances when involved in a traffic accident, that analyze proposed legislation to force automakers to build safer vehicles, or that provide a historical evaluation of the most dangerous intersections in your city.

Story ideas can come from periodic checks with agencies, departments, and groups that regularly are involved in news-making events and issues. So-called beat checks are conducted with law enforcement agencies, legislative departments, nonprofit organizations, military representatives, and other public and private groups to determine if anything newsworthy has occurred, is occurring, or is likely to occur. Such checks often are conducted at least once a day and often several times a day.

Many story ideas come from public relations, public information, or public affairs practitioners (“Journalists Rely on PR Contacts,” 2007). In fact, research has shown that between 50% and 75% of the news stories reported by traditional media organizations have some sort of public relations connection. By using telephones, fax machines, e-mail, Web sites, blogs, text messaging, printed news releases, audio news releases, and video news releases, organizations can inform journalists about newsworthy events, issues, and developments. Such efforts are designed to generate favorable media coverage and gain publicity for clients, but with good reporting, such promotional, advocacy-oriented information can be turned into valid news stories.

Gathering Information

No matter where story ideas come from, to ensure quality journalism, it is critical that solid reporting follows. The gathering of accurate, complete, balanced, and interesting information provides the raw materials that journalists use to produce news stories that inform, educate, entertain, help set public policy, help promote social change (or the status quo), and monitor the activities/decisions of government officials and business leaders (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 8–10; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 44–45). Information can be gathered in a multitude of ways, but most fall into four major categories—reading, interviewing, observing, and experiencing.

Consulting Documents, Databases, and Web Sites

Much information is obtained by reading documents, databases, and Web pages (Alysen, Sedorkin, Oakham, & Patching, 2003, pp. 103–131; Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 95–114; Harrower, 2007, pp. 71–73; Quinn & Lamble, 2008, pp. 59–102). Books, academic journals, trade publications, newspapers, magazines, news releases, faxes, letters, memos, annual reports, case files, posters, billboards, microfiche, and e-mails are read regularly. Databases associated with government agencies, consumer groups, industry organizations, academic institutions, and think tanks are analyzed regularly. Web sites for groups, organizations, departments, agencies, institutions, businesses, and individuals are visited regularly. Blogs are another favorite information source for many journalists (Quinn & Lamble, 2008, pp. 29–41; “Survey,” 2008). Not everything you read in a document, database, blog, or Web site is true, of course, but it’s important to consult a variety of such sources as part of the reporting process.

It’s critical that reporters evaluate the quality of documents, databases, and Web sites. Who are the authors, and what are their qualifications? Who paid for the information to be made public? What’s included, and what’s excluded? Why is information included or excluded? How current is the information? Is attribution clear and sufficient? Any grammar, spelling, or punctuation mistakes? By answering such questions, reporters usually can feel confident that the information they’re sharing with the public is accurate, timely, fair, and balanced.

Talking to People

Interviewing often is the main information-gathering technique used in news reporting (Alysen et al., 2003, pp. 101–117; Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 42–60; Gibbs & Warhover, 2002, pp. 183–204; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 94–111; Harrower, 2007, pp. 76–79). Talking to people, having conversations with people, is a good way to obtain answers to important questions. In addition, it’s an invaluable tool in achieving one of the main goals of journalism— to get people to explain why they believe what they believe, why they value what they value, and why they do what they do. What better way to accomplish this critical part of the journalistic mission than to get the information directly from the people involved in significant events and issues?

Interviewing can be done face-to-face, on the phone, via regular mail, via e-mail, and via text messaging. Face-to-face interviewing is preferred because it allows the interviewer to make note of nonverbal communication and environmental factors, but sometimes it is difficult, if not impossible, to meet with sources, and it takes time to make appointments and travel to interview locations. Phone interviews lose the observation component but retain some of the “human communication” aspects of face-to-face meetings and can be an effective way to gather timely information. Regular mail takes time, and the interviewer loses some control over who actually answers the questions. E-mail and text messaging can produce quicker results than regular mail, but again, some control of the interview scenario is lost, and, as with regular mail, spontaneity is not what it could or should be. Sources have plenty of time to plan their responses to make themselves and their organizations look as good as possible.

Getting people to talk about their beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors is not always easy, especially if they’re shy, stressed, grieving, in shock, fearful, distrustful, embarrassed, guilt-ridden, angry, or annoyed. Most of the time, most people are cooperative and willing, if not eager, to be interviewed; however, when people are reluctant to speak to journalists, several techniques can be employed in an effort to persuade the hesitant person to agree to talk. A journalist might attempt to develop a rapport with the person. A brief chat about the weather, sports, popular culture, or some other relatively nonthreatening subject can help calm an agitated or suspicious person. A journalist might start an interview with relatively innocuous questions before delving into the tougher, more threatening subjects.

A journalist might offer anonymity or confidentiality to a reluctant interview subject. Sometimes, a person will provide information if he or she knows that his or her name will not appear as part of the news story. The use of anonymous or confidential sources can damage credibility and sometimes results in the passing along of inaccurate information, so offers of anonymity or confidentiality normally are given as a last resort when all other methods to convince a person to talk have failed.

Effective, efficient interviewing truly is an art. You can enhance your chances of conducting artful interviews by following a few, basic guidelines. If time permits, and most often it does, it’s critical to do as much “backgrounding” as possible prior to meeting with your interviewee(s). Backgrounding involves finding out as much information as you can about the person(s) and subject(s) you’ll be dealing with. The benefits of such efforts include being able to ask better, more pointed questions; being able to better understand what the person is talking about; being able to gather useful information that you won’t have to waste valuable interview time gathering; and being able to establish a better rapport with your sources by having greater knowledge and insights about what they have done and are interested in. Backgrounding can be done by surfing the Internet, consulting databases, reading books, reading magazines, reading newspapers, reading news releases, visiting libraries, checking your news organization’s archives, talking with your colleagues, talking with friends of interviewees, talking with family members of interviewees, and talking with associates of interviewees.

Once you’ve gathered an appropriate amount of background information, you can begin to finalize the process of developing specific questions to ask your source(s). It’s a good idea to prepare a list of questions, a long, complete list. Creating a list helps build confidence, provides a roadmap for the interview, and gives you something to fall back on if memory fails or a source refuses to answer your first couple of questions. Don’t be too tied to your list, though. Be ready to depart from the list if the interview takes off into new, interesting, and unanticipated territory. Be flexible, and ask spontaneous or follow-up questions when appropriate. Always be on the lookout for unique angles and information. If they come up, explore and develop them. They’ll likely be more interesting and/or important than what you had planned to explore.

You won’t be able to pick up on unexpected interview paths if you don’t listen to what sources say in response to questions. Too often, reporters really don’t listen to what sources say in response to questions. This is especially true if the interview is being recorded. No matter what the situation and what technological assistance you have, listen carefully and analytically. Ask follow-up questions. Ask for clarifications and explanations. Take notes, too. Taking notes is a good form of feedback for the source. It shows that you care enough to write down what he or she is saying. If you’re interviewing a source over the phone, let him or her know that you’re taking notes. Taking notes can save you time when it comes to preparing your final product (you won’t have to listen to the entire recorded interview over again), and you never know when a recording device might fail you.

Be sure you’re talking to the right people about the right things, events, and issues. If you’re reporting about renewable energy sources, talk to experts on that specific subject. You also might want to talk with experts in related fields, but your main focus should be interviewing on-point, onissue experts. Ordinary people who are or who likely will be affected by or who are associated with the issues can provide useful information, too.

Strive for a balance among your sources. It’s traditional that journalists attempt to include all (or as many as possible) sides of an issue. That means talking to proponents and opponents and those on the fence. In addition, it’s critical to balance sources on as many dimensions as possible, including age, gender, race, occupation, educational attainment, political party, income levels, geography, and religious affiliation. You won’t always be able to achieve complete balance for every story, but it’s a good goal to have, and over time across the variety of stories you’re likely to do, it’s an important one to achieve. Society needs and deserves as complete a picture and understanding of the beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors of its members as possible. It’s the job of journalists to provide that picture and help in developing that understanding.

Good interviewers use a variety of approaches to elicit information from sources. Being flexible in your approach is the key. Sometimes you need to be a source’s “friend.” You need to be a sympathetic listener. You need to let the person vent and/or unburden himself or herself. At other times, you need to be more aggressive and assertive, perhaps even demanding and/or threatening. Your job is to gather information. Your job is to get people to give you information by answering your questions. Within reason, you need to do what is necessary to persuade people to answer your questions. Use your interpersonal skills to judge the situation and to get a “read” on the people you need to interview. Most of the time, a courteous, respectful, calm, and straightforward approach works best and is the most professional. Most sources generally will respond favorably to such an approach. Occasionally, when people who should talk to you are reluctant to talk to you, a more forceful, adversarial approach is necessary. Remember that nobody has to talk to you, but public officials and regular newsmakers normally ought to talk to you. The public doesn’t have an absolute right to know absolutely everything, but it does have the right to know as much as possible. Journalists can help make that happen if they do their jobs as information gatherers well.

Quite often, it’s a good idea to let your interview subjects know what you want to talk to them about before you actually go to conduct the interview. If you need to gather specific statistics or acquire specific historical information, let your sources know what you need and give them enough time to find it. A prepared interview source normally is a good interview source. There are times when you want more spontaneity in your interviews. In such cases, you might want to be a bit more general in your request for an interview. Perhaps you don’t want your sources too prepared or too rehearsed. You might want their “top-of-the-head” responses. This is especially true when you’re dealing with sensitive, embarrassing, or incriminating evidence.

Going Where the Action Is

Observing the activities of people and animals, how machines and technologies operate, plus what environmental factors exist often can provide important bits of information that can be used in news stories (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 369–370; Gibbs & Warhover, 2002, pp. 208–221; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 72–84; Harrower, 2007, pp. 72–73). Carefully noting who does what to whom and with what effect, plus where it’s done, when it’s done, and why it’s done, is critical. Noting the sights, sounds, actions, smells, and textures associated with environments helps journalists get a better feel for what the people involved in newsworthy events and issues are dealing with. It can help provide important clues for why people believe what they believe, value what they value, and do what they do.

Normally, journalists observe participants without actually participating themselves. Participant observation involves going to where the participants are and noting what they do and what they say. Generally, information is gathered rather unobtrusively, with the journalist remaining relatively passive, a sort of “fly on the wall.” It is critical that the journalist avoid doing or saying anything that might cause the participants to act significantly differently than how they normally act. Eventually, of course, a journalist will need to ask questions and become a bit more intrusive, but early on, it’s usually best simply to observe and take note of what takes place. If it becomes necessary, advisable, or desirable for a journalist to become an actual participant, care must be taken to avoid behavior that might cause participants to become self-conscious or to act “abnormally.” Becoming an actual participant is fraught with ethical dilemmas and other problems, so in “hard news” situations, it’s best to get involved only if participation seems necessary to earn the confidence and/or cooperation of the participants. In “soft news” or feature-reporting situations, becoming a participant can be an effective way to gain a greater understanding of what participants face. It can be an effective way to tell their story.

Just Do It

Journalists can gather valuable information by experiencing things for themselves (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 369–370; Gibbs & Warhover, 2002, pp. 208–221; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 72–84; Harrower, 2007, pp. 72–73). They can wear a fat suit to see how overweight people are treated during an average day. They can get a job as a fast-food worker. They can go back to school and become a student again. They can try to hit a fastball from a professional baseball pitcher. They can do just about anything, of course, but do they do it as an announced journalist or do they go “undercover” in a type of covert “sting” operation?

In most cases, it’s more professional for a journalist to identify himself or herself as a journalist, but sometimes a journalist can obtain more valuable, more accurate, and more revealing information if he or she goes undercover. Again, such extreme information-gathering methods normally are used only as a last resort when the more common and acceptable methods of information gathering have failed.

While observing participants or actually participating, journalists should be on the lookout for any written materials that might help them with their stories. Official documents, flyers, brochures, catalogs, memos, letters, contracts, bulletin board announcements, salary schedules, files, evaluation forms, diaries, journals, annual reports, Web site content, and mission statements can all provide useful information for the public and help journalists gain a greater understanding of the issues facing the participants.

Typical News-Gathering Situations/Stories

There are five typical news-gathering situations/stories that confront journalists on a regular basis—advance stories, scheduled/expected events, unscheduled/unexpected events, follow-up/reactive stories, analyses/commentaries, and enterprise stories (Harrower, 2007, pp. 66–87). Advance stories include pre-meeting, pre-speech, pre-news conference, and any other pre-event coverage. Often, such stories are designed to let people know if attending an event is worth their time, energy, and money. Such stories also can provide preview examinations of critical issues, help put things in perspective, and help develop needed meanings associated with events. The five Ws and the H come into play, of course, but good reporters go beyond the basics and seek out expert evaluations and insights about the critical issues likely to surface during the upcoming events.

Scheduled/expected events include meetings, speeches, news conferences, concerts, demonstrations, and sports events. In such situations, reporters need to keep in mind that many other journalists will be in attendance, so it is important to look for unique, or at least different, angles to report about. All the basic information should be gathered, of course, but an effort must be made to find something that can serve as a unique focus for your story. Such things often can be found by gathering anecdotes from participants, taking special note of environmental factors/features, concentrating on causes/effects/alternatives, and simply asking participants what’s different about this particular event or the subjects talked about during the event. Another thing that good reporters do is to supplement the information they obtain from “official” sources—spokespeople, handouts, agendas—with information from people who are or will be affected by what takes place during scheduled/expected events. Such events should be part of the informationgathering process, not the end of the process.

It’s important to learn as much as you can about the people and issues associated with scheduled events prior to attending the events. By doing a good job of backgrounding, journalists increase their chances of doing more meaningful, insightful event coverage. Other tips include arriving early and staying late; sitting up front; taking notes; making sure you keep the names straight of who says what; noticing environmental factors; noticing audience reactions to comments and decisions; noticing nonverbal language; asking questions of the participants; asking questions of audience members; asking questions of people who will be affected by what happens during the event; asking follow-up questions if you don’t get an adequate response to a question; asking follow-up questions to other reporters’ questions if necessary; analyzing why the event was scheduled; and finding out what the organizers hoped to achieve and whether they achieved it.

Unscheduled/unexpected events include traffic accidents, plane crashes, fires, robberies, murders, hostage situations, floods, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions. Once again, it’s likely that many journalists will be reporting about the same events, so, after getting answers to all the basic who, what, where, when, why, and how questions, good reporters look for unique angles to differentiate their stories from their competitors’ stories. Humanizing the story—telling it by focusing on one person, family, or small group—is one common technique used.

Follow-up/reactive stories include “day-after” reporting of major events, getting responses from people affected by major governmental or big business decisions/developments, and finding related information when a competitor has a story you don’t have. Follow-up/reactive stories almost always deal primarily with issues. It’s important to get a variety of reactions from the people involved in events and issues, but it’s also important to get a variety of comments from sources who have expertise in the areas being explored but who do not have any real stake in what is taking place or has taken place. These so-called “referee sources” include lawyers, doctors, professors, and officials outside the geographic area covered by a local news organization.

Analyses/commentaries include more personalized, indepth explorations of events and issues. Such stories require detailed information gathering. Reporters need to find information that will help them create a greater understanding of the five Ws and the H among audience members. In many cases, reporters need to find information that will help them persuade audience members to change their beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors. Such efforts require consulting multiple sources of information, conducting numerous interviews, and making extended observations.

Enterprise stories include investigative reports, in-depth features, and unique-lifestyle explorations. Such stories require voluminous information gathering. Reporters must search through numerous documents, conduct numerous interviews, use a variety of observational techniques, and verify, verify, verify (Ettema & Glasser, 1998, pp. 139–153). Very often, the reputations of important people and influential organizations are involved. Reporters must take great care that the information they include in their final products is as accurate, complete, balanced, and fair as possible. Reporters generally get much more time to produce enterprise stories, so they are expected to discover new sources of information and to explore such sources more fully so that they can produce stories that break new ground and reveal little-known facts about the important people and institutions in society.

What Interests Audience Members?

In any news-gathering situation, it is critical for a reporter to take into consideration the topics and things that people are interested in and care about (Brooks et al., 2008, p. 6; Campbell, 2004, pp. 104–125; Hansen & Paul, 2004, pp. 31–35; Harrower, 2007, p. 17). Attempts should be made to obtain as much information about such topics and things as possible in the time available prior to the deadline. News values/elements/qualities help in this area, too, but there are many more topics and things that people find interesting.

People are interested in events and issues that affect them in some way. They are interested in what well-known people say and do. They are interested in knowing about timely “breaking news.” They are interested in conflicts between people, groups, organizations, and countries. They are interested in achievements and the setting of records. They are interested in acts of courage and heroism. They are interested in sex and romance. They are interested in what animals do. They are interested in money. They are interested in what things cost and what benefits are associated with such costs. They are interested in winners and losers, pros and cons, advantages and disadvantages, causes and effects, impacts and meanings. They are interested in what has happened in the past and what will or might happen in the future. They are interested in what alternatives may be available to deal with current problems and situations. They are interested in timetables and the timing of events and issues. They are interested in the size of things, the number of things, and the frequency of things. They are interested in steps, procedures, and processes. They are interested in requirements, limitations, and parameters. They are interested in demographics—age, gender, occupation, educational attainment, religion, politics.

One of the worst things that can happen after a news story has been printed, broadcast, or made available online is for audience members to say “So what?” or “Who cares?” An important goal of every information-gathering effort should be to obtain information that will answer such questions. Normally, such information surfaces as part of the reporting process, but if it doesn’t, a reporter must revisit sources or develop new sources to be sure that impacts/meanings are clear and that important stories are made interesting and interesting stories are made important.

The five Ws and the H provide a good framework for information gathering (Gibbs & Warhover, 2002, pp. 102–117; Hansen & Paul, 2004, p. 55). Of course, there are many more Ws than five and many more Hs than one. In fact, for most stories, the Ws and the Hs are just about endless. They include the basic who is involved, what has happened, where did it take place, when did it take place, why did it happen, and how did it happen? They also include the following:

Getting Access to Information

Freedom of the press is a relatively empty freedom if information gatherers are prohibited from obtaining the information they need to satisfy the public’s right to know about significant events and issues (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 390–393; Garrison, 1992, pp. 249–251). No person can be forced to speak to a reporter, but thankfully, most sources are either relatively willing to speak to journalists or at least can be persuaded to talk. Sunshine laws protect the right of journalists to attend meetings of public groups, and freedom-of-information laws protect the right of journalists to obtain copies of public documents. There are exceptions, of course, but most of the time, journalists have the right to sit in on meetings and official proceedings and the right to examine reports and other documents produced by governmental agencies.

If reporters get answers to as many of the five Ws and the H questions as possible, it’s unlikely that audience members will be able to say “So what?” or “Who cares?” after reading, listening to, or watching news stories.

Accurate, Balanced, and Fair Information

Before reporters introduce information in their stories, they should be convinced that the information is accurate, balanced, and fair (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 10–15). Normally, this can be accomplished by getting the same information from multiple sources. Confirming information, validating it, and vetting it are critical steps in the reporting process. It’s especially critical when dealing with sensitive, revealing, embarrassing, or incriminating information. Most news organizations require that a reporter have at least two sources, preferably three sources, that contain or that have offered the same, or very similar, information. Double-checking and triple-checking facts, figures, quotes, allegations, assertions, perceptions, and opinions must be a regular part of any legitimate, quality newsreporting effort.

Legal and Ethical Problems

Failing to confirm and validate information prior to sharing it with the public can lead to a variety of legal and ethical problems (Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 464–513; Campbell, 2004, pp. 126–152). Over-the-top, overly aggressive, out-of-control, mean-spirited, biased, and revenge-motivated reporting can have the same result. Typical legal and ethical problems include libel, invasion of privacy, copyright infringement, fabrication, plagiarism, sensationalism, and conflicts of interest.

Libel occurs when journalists report false information that damages a person’s reputation. Invasion of privacy can occur when journalists use hidden microphones/cameras, go onto private property, falsely attribute information or endorsements to people, or give a false impression of a person to the public. Copyright infringement can occur when journalists “borrow” information from printed sources without providing proper attribution.

Fabrication is one of the major taboos in journalism. Information and quotes should never be made up. Plagiarism is another taboo. Taking the work of another writer and passing it off as your own should never be done. Embellishing and/or exaggerating information to dramatize and sensationalize the news have limited initial benefits—higher ratings and circulation, but in the long run, such tactics usually lead to audience dissatisfaction, distrust, and disbelief. Conflicts of interest can result when reporters have a stake in the topic on which they’re reporting. They might have a financial interest in a piece of real estate or own stock in a company that they’re asked to report about. They might be asked to report about a group or organization to which they or their family members or friends belong.

Legal and ethical problems can lead to a loss of credibility for a news organization. Since credibility is one of the major things that news organizations “sell,” any loss of credibility can lead to a reduction in ratings, readership, or circulation. Reporters must do everything they can to ensure that the information that reaches the public is as accurate, complete, balanced, and fair as possible. Deadlines and difficulties associated with gathering all the information that’s needed can sometimes result in some inaccurate, incomplete, unbalanced, and unfair information reaching the public, but such instances can be kept to a minimum if reporters do their jobs well and care about informing and educating the public.

Editing Improves Quality

Careful, rigorous editing by reporters, editors, and news managers can help avoid many of the legal and ethical problems that often plague journalists (Alysen et al., 2003, pp. 132–148; Brooks et al., 2008, pp. 73–79). Editing can improve accuracy. It can remove redundancies. It can increase preciseness and conciseness. It can eliminate grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. It can help ensure consistency in style and tone.

The editing process begins when reporters check, double-check, and sometimes even triple-check their facts. Fact checking also is done by editors and news managers. Some news organizations even have designated “fact checkers.” Everyone’s goal is to avoid passing along inaccurate, misleading information. One technique that helps ensure that information is accurate is to perform simple mathematical calculations whenever numbers are involved in a story. “Do the math” and/or “Check the math” are common commands/expectations in newsrooms (Alysen et al., 2003, pp. 132–148; Harrower, 2007, pp. 84–85). By adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing numbers, journalists can catch their own mathematical mistakes and those of their sources.

For example, a reporter writes that a local business has 10,000 customers and takes in an average of $5,000 each day. Simple division results in an average expenditure of 50 cents per customer. Since nothing the business sells even costs 50 cents or less, clearly an error has been made. It might be that the reporter transposed the numbers or misunderstood the business’s accountant. It might be that the accountant misspoke. In any case, the inaccurate information should not be passed along to the public. A call, e-mail, or visit to the accountant should be made to determine the correct figures.

Another common editing practice is to look for “red flag” words, phrases and constructions. For example, whenever the word there is used in a story, reporters, editors, and news managers need to consider whether the use of there is correct or whether the word should be their or they’re. In addition, is the correct word to be used it’s or its? Is it to, too, or two? Is it who or whom?

Other editing concerns include the following: Do subjects and verbs agree in number? Does the copy flow? Are more transitions needed? Are there any awkward or confusing spots? Are quotes inserted and punctuated properly? Is more attribution needed? Does more information need to be gathered and presented? Has proper style been used?

The Associated Press Stylebook (2008) is a good resource for reporters, editors, and news managers. It includes recommended guidelines for abbreviations, numbers, capitalization, punctuation, and other typical contentrelated issues. It even includes tips for handling polls and surveys, plus how to avoid libel and ethical problems.

Conclusion

One of the fundamental keys to successful journalism is the ability to “tell a good story.” No matter what medium has been used, is being used, or will be used in the future to convey information to people—print, radio, television, online, cellular, holographic, journalists—if they’re to be successful, have to present interesting and important information in an attention-getting, entertaining manner. Identifying important and interesting people, events, and issues to report about is the first part of the process. By doing so, journalists play a key role in keeping the public informed, educated, and entertained.

Doing quality reporting—gathering important and interesting information—is the second part of the process of telling a good story. Finding out what people believe, what they value, and what they do, plus why they believe what they believe, why they value what they value, and why they do what they do helps us all gain greater understanding of our own culture and the cultures of others. Gathering information in a legal and ethical manner is important, too.

Editing the story to ensure accuracy, completeness, clarity, fairness, and balance; to improve grammar, spelling, and punctuation; and to improve the flow and readability of the story is the final part of quality storytelling. In most cases, the entire process—coming up with an idea, reporting and editing the final product— must be completed in less than 24 hours, and often the process must be completed within an hour or two. No matter how much time a journalist has to develop and present a story, the goal is still the same. Make important people, events, and issues interesting, and make interesting people, events, and issues important.

Bibliography:

- Alysen, B., Sedorkin, G., Oakham, M., & Patching, R. (2003). Reporting in a multimedia world. Crows Nest, New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

- Associated Press Stylebook. (2008). NewYork: Associated Press.

- Brooks, B. S., Kennedy, G., Moen, D. R., & Ranly, D. (2008). News reporting and writing (9th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Campbell, V. (2004). Information age journalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ettema, J. S., & Glasser, T. L. (1998). Custodians of conscience: Investigative journalism and public virtue. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Garrison, B. (1992). Advanced reporting: Skills for the professional. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gibbs, C., & Warhover, T. (2002). Getting the whole story: Reporting and writing the news. New York: Guilford

- Hansen, K.A., & Paul, N. (2004). Behind the message: Information strategies for communicators. Boston: Pearson Education.

- Harrower, T. (2007). A practical guide to the craft of journalism. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Houston, B. (2004). Computer-assisted reporting. New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Izard, R. S., & Greenwald, M. S. (1991). Public affairs reporting: The citizen’s news. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown.

- Journalists rely on PR contacts, corporate Web sites for reporting, survey says. (2007, November 19). PR tactics and The Strategist Online. Available at: http://androbinson.com/uploads/8/8/6/6/88661310/pranding_online.pdf

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2001). The elements of journalism. New York: Crown.

- Levy, M. R. (1978). The audience experience with television news. Journalism Monographs, 55.

- Levy, M. R., & Windahl, S. (1984). Audience activity and gratifications: A conceptual clarification and exploration. Communication Research, 11, 51–78.

- Metzler, K. (1997). Creative interviewing. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Meyer, P. (2002). Precision journalism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Pember, D. R. (2003). Mass media law. Dubuque, IA: McGraw-Hill.

- Quinn, S., & Lamble, S. (2008). Online newsgathering: Research and reporting for journalism. Burlington, MA: Focal Press.

- Reese, S. D., & Ballinger, J. (2001). The roots of a sociology of news: Remembering Mr. Gates and social control in the newsroom. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 78, 641–658.

- Stepp, C. S. (2007). Writing as craft and magic. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vishwanath, A. (2008). The 360º news experience: Audience connections with the ubiquitous news organization. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 85, 7–22.

- Wilkens, L., & Patterson, P. (2005). Media ethics: Issues and cases. Dubuque, IA: McGraw-Hill.