View sample school-related behavior disorders research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The focus of this research paper is on the behavior disorders of children and youth, which are increasingly manifested within the context of schooling. Children by the thousands now appear at the schoolhouse door showing the damaging effects of prior exposure to family-based and societal risks (abuse, neglect, chaotic family conditions, media violence, etc.) during the first 5 years of life. Our society has begun to reap a bitter harvest of destructive outcomes among our vulnerable children and youth resulting from such risk exposure and from our seemingly diminished capacity to rear, socialize, and care for them effectively. It is now not uncommon for as many as half of the newborns in any given state to suffer one or more risk factors for later destructive outcomes and poor health (Kitzhaber, 2001).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

The characteristics, needs, and demands of these children and youth have overwhelmed the capacity of schools to accommodate them effectively. Ironically, our school systems have been relatively slow to recognize the true dimensions of the challenges that these students pose to themselves, to the social agents in their lives, and to the larger society. Recent estimates by experts of the number of today’s youth with significant mental health problems reflect the destructive changes that have occurred in the social and economic conditions of our society over the past 30 years. Angold (2000) estimated that approximately 20% of today’s school-age children and youth could qualify for a psychiatric diagnosis using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychological Association, 1994). Hoagwood and Erwin (1997) argued that about 22% of children and youth enrolled in school settings have mental health problems that warrant serious attention and treatment. Slightly less than 1% of the school-age population is served as emotionally disturbed under provisions of the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA, 1997), which illustrates the enormous gap that currently exists between need and available supports and services for these students in the school setting.

In a recent Washington Post investigative report on the changed landscape of problem behavior and its impact on schooling,Perlstein(2001)providedelaboratedocumentation of the increasingly outrageous forms of behavior displayed by younger and younger children and concluded that our schools are “awash in bad behavior” (p. B1). She described elementary school students who defied their teachers and called them obscene names, who threatened them with physical violence, who attacked their peers for no apparent reason, who brought drugs and weapons to school, who destroyed classroom furnishings when disciplined, and whose parents denied their child’s culpability in these incidents and refused to take ownership or responsibility for dealing with them. In addition, Perlstein provided compelling evidence of national trends involving the rising use of school suspensions and expulsions of very young children, the creation of school-based detention centers, and investment in alternative educational programs and personnel—all increasing dramatically at the elementary school level. Educators perceive the costs of these accommodations as taking dollars away from needed school reform efforts designed to increase educational accountability and achievement levels.

The larger society has finally begun to express concern about our troubled children and youth and to assemble experts from multiple disciplines to create policy, develop legislative initiatives, and construct action plans that will address this growing national problem. For example, in September 2000, the U.S. Surgeon General convened a national conference on children’s mental heath, involving a collaboration between the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Education, and Justice, to develop a national action agenda that balances health promotion, disease prevention, early detection, and universal access to care. This conference produced an influential report titled Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda, which provides a blueprint for action on this critically important topic.

In a more reactive vein, the widely publicized schoolshooting tragedies of the 1990s have shocked us into action and cast a national spotlight on the problems that young people daily experience with bullying, emotional abuse, and harassment at the hands of their peers. It is estimated in media reports that approximately 160,000 U.S. students miss school each day because of bullying. When mixed with mental health problems (severe stress and anxiety, depression, paranoia) and the desensitizing effects of pervasive exposure to violence in the media, the toxic consequences of bullying can pose a real risk of tragic outcomes in the context of an abused student seeking revenge—a recurring pattern that we have seen in school shootings. Kip Kinkle, who went on a school-shooting rampage at Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon, in 1998 after murdering his parents, was an exemplar of this combination of destructive attributes. The Thurston shooting prompted a collaborative effort between the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice (in which the senior author was a participant) that created a national panel of experts who produced two resource guides sent to every school in the country: Early Warning/Timely Response: A Guide to Safe Schools and Safeguarding Our Children: An Action Guide. Implementing Early Warning, Timely Response. The first document focused on warning signs and early detection; the second provided guidelines for implementing the Early Warning/Timely Response guide.

Schools have now realized that these complex problems cannot be dealt with through a business-as-usual approach. School administrators are searching for and considering an array of strategies that will help make schools safer and more effective; they are now open to prevention approaches in ways that have not heretofore been in evidence. The spate of tragic school shootings over the past decade prompted a strong investment in school security technology by educators and created pressures for the profiling of potentially dangerous, troubled students. Neither approach has been demonstrated as particularly effective in making schools safer or free of the potential for violence. Profiling has very serious downside risks for student victimization through damage to reputations (Kingery & Walker, 2002).

School administrators have been generally open to,but less enthusiastic about, investing in comprehensive, positive, behavioral-support approaches that (a) create orderly, disciplined school environs; (b) establish positive school cultures; and (c) address the needs of all students who populate the school. Perhaps this is the case because these programs require up to 2 years for full school implementation. Two of the best known and most cost-effective approaches of this type are the Effective Behavioral Support (EBS) and Project Achieve intervention programs developed respectively by Horner, Sugai, and their associates at the University of Oregon and Knoff and his associates at the University of South Florida. Both of these proven model programs are profiled in Safeguarding Our Children: An Action Guide. Implementing Early Warning, Timely Response (see Dwyer & Osher, 2000).

The development of comprehensive interagency collaborations that address primary, secondary, and tertiary forms of prevention is an investment that schools have yet to make to any significant degree. However, to reduce and actually reverse the harm caused by the broad-based risk exposure experienced by today’s children and youth, it will be necessary to scale up and mount such collaborative initiatives with good integrity (Eddy, Reid, & Curry, 2002).

Behaviorally at-risk children and youth provide a funnel through which the toxic social conditions of our society spill over into the school setting and destructively impact the capacity of our schools and educators to provide for these vulnerable students the normalizing and protective influences of schooling. This growing student population increasingly stresses and disrupts the teaching-learning process for everyone connected with schooling. The peer cultures of schools grow ever more corrosive, and there are more incidents of challenges to school authority and operational routines by angry, out-of-control students. School personnel, perhaps understandably, regard members of this student population with suspicion because of the large number of school-shooting tragedies that have occurred over the past decade. At the other end of the spectrum, significant numbers of today’s students experience severe anxiety and depressive disorders primarily of an internalizing nature.

This research paper focuses on the topic of behavior disorders (BD) in the context of schooling and is written from the perspective of the school-based professionals (school psychologists, special educators, school counselors, early interventionists, behavioral specialists) who are specialists in addressing the needs and problems of this behaviorally at-risk student population. Herein, we address three major topics as follows: (a) the critical issues that have shaped and continue to influence the field of behavior disorders; (b) the adoption and delivery of proven, evidence-based strategies that have the potential to divert at-risk students from a destructive path and that contribute positively to school engagement and academic success; and (c) the content of interventions for addressing the adjustment problems of BD students within the school setting. The paper concludes with some brief reflections on the future of the BD field and directions it should consider for its future development.

Critical Issues Affecting the Field of Behavior Disorders

BD professionals working in higher education and school and agency settings are uniquely positioned, and qualified, to have a positive impact on the needs, challenges, and problems presented by the behaviorally at-risk student population. They have intimate knowledge of schools and their cultures; they know instructional processes and routines; and they are experts in behavior change procedures. No other professional combines these types of skills and knowledge. As a rule, BD professionals are strongly dedicated to improving the lives of these children and youth through the direct application of the strategies and techniques that they have been taught for changing behavior in applied contexts. However, as our society’s problems have worsened, the results of their intervention efforts look less and less impressive in the face of schools that have been transformed into fortress-like structures and student populations that continue to be out of control.

The BD field has developed some seminal contributions to our understanding of school-related behavior disorders along with methods for addressing them, but this knowledge base and these proven practices are often not in evidence in the daily operation of schools. The gap between what is known and proven and what is practiced is no where greater than in the field of school-related behavior disorders. This section is divided into two major topics that focus, respectively, on “What is Right with Behavior Disorders?” and “What is Wrong with Behavior Disorders?” We believe that the critical issues affecting the BD field can be effectively illustrated using this dichotomy. Before dealing with this set of issues, however, we would like to put the BD field in context relative to its role as a resource to schools in dealing with behaviorally at-risk students and its status as a subspeciality of the larger field of special education.

The Current Landscape of Behavior Disorders as a Field

The field of behavior disorders, as a disciplinary subspecialty of general special education, is a relatively new field dating from the early 1960s. Frank Wood (1999) recently profiled the history and development of the Council for Children with Behavior Disorders (CCBD) in this regard.

Although encompassing diverse philosophical and theoretical approaches, the field has generally maintained a consistent focus on empirical research and has provided important journal and monograph outlets for the contributions of its researchers and scholars. The Journal of Behavioral Disorders, the CCBD Monograph Series, the Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, and Education and Treatment of Children are excellent examples of peer-reviewed publications that publish high-quality research and commentary in the BD field. These outlets and their respective editors have advanced the field’s development and have contributed enormously to the cohesive knowledge base that we see today relating to the social, emotional, and behavioral status of at-risk children and youth in the contexts of school and community.

The field of behavior disorders can trace its roots to the use of behavior change procedures with mentally ill children and youth within highly restrictive settings (mental institutions, residential programs) and to the delivery of mental health services for the emotional problems of vulnerable children and youth within school and community settings. Over the past three decades the number and severity of the problems manifested by children and youth, who are referred to as having emotional disorders (ED) or behavior disorders, have changed substantially (Walker, Zeller, Close, Webber, & Gresham, 1999). Early in our field’s development the children and youth referred and served as having emotional disorders had primarily mental and emotional problems (depression, social isolation, self-stimulatory forms of behavior, etc.). Problems representing critical behavioral events, sometimes involving a danger to self and others, such as severe aggression, antisocial behavior, vandalism, cruelty to animals, and interpersonal violence, were rarely dealt with by BD professionals.

It is clear that thousands of young children in our society are being socialized within chaotic, abusive family and community contexts in which they are exposed to a host of risk factors that provide a fertile breeding ground for the development of highly maladaptive attitudes, beliefs, and behavioral forms. These risk factors can operate multiply on an individual across family, community, school, and cultural contexts. They are registered in unfortunate life paths that are often tragic and involve huge social and economic costs. We now see comorbid mixtures of syndromes (conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD) in school-age children that are efficient predictors of adult psychopathology (see Gresham, Lane, & Lambros, 2000; Lynam, 1996).

Professionals in the field of behavior disorders are charged with effectively accommodating this changed population of children and youth within the context of schooling. The presence, risk status, and intense needs of these students place powerful stressors on the ability of schools to serve them; they present a continuing and significant challenge to BD professionals and to the field. Increasingly, educators are having to forge partnership arrangements with mental health and other social service systems in order to meet the needs of these individuals, their families, and their caregivers.

In our view, the field of behavior disorders possesses the knowledge and skills necessary to accommodate the majority of behaviorally at-risk children who must be served by schools. However, for those children who enter the schoolhouse door having severe tertiary-level involvements, schools will find it necessary to continue forging effective partnership arrangements with nonschool service systems such as mental health. We see this development as a positive one that should be promoted and enhanced. The advent of family resource centers, attached to school districts, provides an excellent vehicle for the coordination and delivery of such approaches.

Today, BD professionals at all levels are challenged as they have never been before. Continuing to serve students having mental health needs primarily under the aegis of the ED category of special education is no longer viable. The intensity of need and the sheer numbers of affected individuals are simply too great, and the consequences of not serving this growing student population are both tragic and ominous. Schools, in collaboration with community agencies, must find new ways of responding to this service need that continues to grow and expand. The BD professional can play a powerful role in building a new service delivery infrastructure for meeting this critical need and making sure that schools are key players in developing viable solutions to this societal problem that we all own collectively.

What Is Right With Behavior Disorders?

Because of the quality of the BD field’s cadre of professionals, its consistently empirical focus, strong commitment to best and preferred practices, and the diversity and rigor of its methodological tools and approaches, the field has a welldeveloped capacity to contribute innovations that can lead (a) to important outcomes in the lives of youth with emotional disorders and (b) to the enhancement of the skills and effectiveness of online BD professionals (Walker, Sprague, Close, & Starlin, 2000). Many of these contributions can be documented as they operate currently within general education contexts. Some examples include the following:

- The roots of many standards-based school reforms and performance-based assessment systems can be traced to behavioral psychology and applied behavior analysis.

- The current emphasis on teaching social skills as part of the regular school curriculum to reduce conflicts and prevent violence results from initiatives by BD and related services professionals.

- The development of behavior management approaches for managing student behavior in specific school settings results from prototype models developed by the BD field.

In recent years the BD field has contributed some advances that (a) increased our understanding of how behaviorally atrisk children and youth come to engage in and sustain their destructive, maladaptive behavior patterns over time; (b) documented how some of our interactions with students with emotional disorders in teaching-learning situations control both teacher and student behavior in negative ways; (c) provided for the universal screening and early identification of school-related behavior patterns that facilitate effective early intervention; (d) documented the relationship between language deficits and conduct disorder among at-risk children and youth; (e) investigated the metric of disciplinary referrals and contacts with the school’s front office as a sensitive measure of the following school climate, the global effects of schoolwide interventions, and the behavioral status of individual students; (f) developed effective, low-cost models of school-based intervention that allow access to needed services and supports for all students in a school; (g) contributed schoolwide, disciplinary and positive behavioral support systems that improve outcomes for the whole school; (h) reported longitudinal, comprehensive profiles of the affective, social-behavioral status of certified, referred, and nonreferred students; and (i) developed the concept of resistance to intervention for use in school-based eligibility determination and treatment selection decisions (Walker et al., 2000). Ultimately, these advances will improve the BD field’s capacity to meet the challenges and pressures of a changed population with emotional disorders and to address proactively the vulnerability of schools in preventing and responding to the violent acts of very disturbed youth such as Kip Kinkle (mentioned earlier). Descriptions of some of these advances and seminal contributions are briefly described below.

Functional Behavioral Assessment

The development and validation of functional behavioral assessment (FBA) techniques and approaches stands as perhaps one of the most important advances in the field of behavior disorders (O’Neill, Horner, Albin, Storey, & Newton, 1997). Functional behavioral assessment (a) provides a usable methodology for identifying and validating the motivations that drive maladaptive forms of student behavior in applied settings, (b) allows for the identification of the factors that sustain such behavior over time, and (c) provides a prescription for intervening on these sustaining variables with the goal of producing fundamental, enduring changes in the rate and topography of problem behavior.

Functional behavioral assessment, which is based on operant learning theory and its application to the learning and behavioral difficulties of children and youth, is derived from the field of applied behavior analysis. The dominant theoretical orientation of the BD field has historically been applied behavior analysis, and its many contributions to BD date back over 30 years. They were chronicled in the edited volume titled Behavior Analysis in Education (Sulzer-Azaroff, Drabman, Greer, Hall, Iwata, & O’Leary, 1988). In 1997 the amendments to IDEA required use of both FBA and positive behavioral supports (PBS) and interventions in evaluating and intervening with students having a possible disabling condition. Prior to this landmark legislation, many BD professionals and behavior analysts considered FBA and PBS to be best practices, but federal law did not mandate their use.

Based on a valid FBA, PBS programming has much to offer the BD community in fulfilling the mandates of IDEA. The 1997 IDEA amendments do not specify what constitutes a valid FBA, nor do they state the essential components of a positive behavioral support plan. However, in the few years since the passage of this law, the BD field has vigorously responded in developing a range of feasible FBA and PBS models and approaches.

FBA methods can be categorized as (a) indirect, using interviews, historical-archival records, checklists, and rating scales; (b) direct or descriptive in nature, using systematic behavioral observations in naturalistic settings; and (c) experimental, employing standardized experimental protocols that systematically manipulate and isolate contingencies that control the occurrence of problem behavior using primarily single-case experimental designs (Horner, 1994; O’Neill et al., 1997). Despite the methodological rigor of functional analysis approaches, there are limitations regarding the external validity of its findings as well as the amount of time and expertise required to conduct a valid functional analysis (Gresham, Quinn, & Restori, 1998; Repp & Horner, 1999). Many of the studies using functional assessment procedures over the past decade were based on low-incidence disability groups, thus limiting the applicability of these results to high-incidence groups.

Walker and Sprague (1999) argued that there are two generic models or approaches to the assessment of behavior problems. One model, termed the longitudinal or risk factors exposure model, grew out of research on the development of antisocial behavior (Loeber & Farrington, 1998) and seeks to identify molar variables that (a) operate across multiple settings and (b) put students at risk for long-term, negative outcomes (e.g., drug use, delinquency, school failure). The second model, called the functional assessment approach, seeks to identify microlevel variables operating in specific situations that are sensitive to setting-specific environmental contingencies. Both models are useful in school-based assessment processes, but they answer quite different questions. If your goal, for example, is to understand and manage problem behavior in a specific setting, the FBAis valuable and should be the method of choice. However, if your goal is to understand the variables and factors that account for risk status across multiple settings and what the student’s future is likely to involve, then knowledge about the student’s genetic-behavioral history(riskfactorexposure)isrequired.Admittedly,theFBA model (primarily functional analysis) suffers from several threats to its external validity; one should not assume that the same results could be generalized to other populations, methods, settings, and behavioral forms.

Despite these limitations, FBA methods represent a valuable tool for the BD professional working in school settings. They hold the potential to identify setting-specific causal factors that account for problematic student behavior, and their use may enhance the power and sustainability of behavioral interventions. However, this latter outcome remains to be demonstrated empirically. Although FBA has its share of critics (see Nelson, Roberts, Mathur, & Rutherford, 1999), this assessment methodology has been widely adopted by BD researchers and professionals and by other disciplines (e.g., school psychology).

Positive Behavioral Support Intervention Approaches

The development of PBS approaches is another significant contribution of the BD field in the area of creating well disciplined, orderly schools with positive school climates. Sugai and Horner (in press) along with their associates have been leaders in this effort and were recently awarded a 5-year center grant from the U.S. Office of Special Education Programs to investigate and promote the adoption of PBS approaches nationwide (see the ERIC/OSEPSpecial Project, winter, 1999 issue of Research Connections in Special Education for an extensive treatment of PBS). This approach has the advantages of (a) targeting all students within a school; (b) coordinating the implementation of universal, selected, and targeted intervention strategies; and (c) focusing on positive, proactive approaches as opposed to punitive, reactive interventions.

Sugai and Horner (in press) developed the EBS program, which is a combined universal-selected intervention that teaches behavioral expectations in both schoolwide and specific contexts (i.e., classroom, playground, lunchroom). EBS is a systems approach to creating and sustaining effective and orderly school environs, and it has now been implemented in over 400 schools nationwide. The program teaches generic behavioral expectations such as being responsible, respectful, and safe and requires complete buy-in from all personnel within the school. Full implementation of the EBS program usually requires 2 or more years.

Office discipline referrals from teachers has been the primary means used to evaluate the schoolwide impact of EBS. In one of the earliest evaluation studies of EBS, Taylor-Green and Kartub (2000) found that the number of disciplinary referrals in an at-risk middle school decreased by 47% in 1 year; after 5 years the initial number of office referrals had been reduced overall by 68% from the pre-EBS level. Astudy by Lewis, Sugai, and Colvin (1998) found that the EBS program also reduced problem behavior within specific school settings including the lunchroom, playground, and hallways. Hunter and Chopra (2001) recently reported a review of primary prevention models for schools, in which they endorsed EBS as a universal intervention that works.

Positive behavioral support is a popular intervention approach with regular educators, and PBS models will likely have a substantial school adoption rate over the next decade. Most significantly, PBS has been incorporated as a required best practice into the reauthorized legislation supporting the 1997 IDEA amendments for students suspected of having a behavior disorder or disability.When used in concert with more specialized intervention approaches that address secondary and tertiary prevention goals, PBS models have the potential to integrate qualitatively different interventions that will comprehensively impact the behavior problems and disorders of all students within a school setting (Walker et al., 1996). This is indeed a rare occurrence in the field of general education.

Analysis of Teacher Interactions With Students With Behavior Disorders

Two important lines of work have recently developed in the BD field relating to the interactions that occur between BD students and their teachers in classroom settings. Together, they shed considerable light on the interactive dynamics and processes occurring in these teacher-student exchanges wherein the behavior of each social agent is reciprocally controlled by the actions of the other. The resulting effects can damage the teacher-student relationship, disrupt the instructional process, and reduce allocated instructional time for everyone.

Colvin (1993) developed a conceptual model that captures the phases of behavioral escalation that a teacher and an agitated student typically cycle through in a hostile confrontation. It begins with the teacher’s making a demand of an agitated student who appears calm but is not. The teacher’s approach serves as a trigger that accelerates the agitation. This acceleration process typically occurs through a reciprocal question-and-answer exchange between the teacher and the student. There is an overlay of increasing hostility, emotional intensity, and anger during these exchanges until the interaction hits a peak, usually expressed as teacher defiance or a severe tantrum. This is followed by a rapid de-escalation and recovery of the calm state. However, seething anger is the usual by-product of this type of interaction, on the part of both teacher and student, which, as a rule, plays out in less than 60 s.

These escalated interactions are usually modeled for and learned by BD students in the family context as dysfunctional families often use a process of coercion to control the behavior of family members (see Patterson, 1982; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). These same types of negative, destructive interactions typically occur between students with challenging behavior patterns and their teachers. They resemble behavioral earthquakes that come out of nowhere, do incredible damage, and require long periods for recovery. This behavioral escalation game is one that teachers should not play for two primary reasons: (a) Even if the teacher gets the better of the student in this public exchange, he or she will likely have created an enemy dedicated to revenge; and (b) if the reverse occurs, the teacher’s ability to manage and control the classroom will be severely compromised and even damaged. It is best to avoid and escape from such escalated interactions whenever possible. Colvin explained how to recognize these developing episodes and how to avoid and short-circuit them (see Colvin, 1993; Walker, Colvin, & Ramsey, 1995).

Shores, Wehby, and their colleagues (see Shores, Gunter, et al., 1993; Shores, Jack, et al., 1993; Wehby, Symonds, Canale, & Go, 1998) have designed and conducted a series of observational studies that spotlight the interplay of precipitating stimuli, setting events and behavioral actions occurring within many of the interactions between BD students and their teachers that occur on a daily basis. Their work confirms key parts of the Colvin escalation model and should be required reading for all prospective teachers, and especially for teachers of students with behavior disorders. The results of their studies also replicate the findings of Patterson et al. (1992) and Wahler and Dumas (1986) with families who produce antisocial children; in these families family members learn to control each other’s behavior through aversive means including punishment and coercion. This same coercive process spills over into the school setting and is replicated with teachers by these behaviorally at-risk children. That is, the effect of the student’s behavior on the teacher is highly aversive, leading to reduced levels of praise, negative student recognition, and less instructional time. Ultimately, both teachers and students come to view these exchanges, and the classroom environment, as punishing. This can lead to escape and avoidance forms of behavior by both parties. Wehby et al. (1998) developed a set of teaching recommendations, based on results of this work, that should be incorporated into preservice teacher preparation programs and adopted by experienced teachers as well.

The Relationship Between Language Deficits and Conduct Disorder

Hester and Kaiser (1997) investigated the relationship between conduct disorder and language deficits and examined the conjoint risk factors (impoverished language environs, poverty, social stressors, and coercive family dynamics) that produce children who are both highly aggressive and very unskilled in their functional use of language. These investigators have developed an intriguing social-communicative perspective on the prevention of conduct disorder using early language intervention. This work involves both descriptive and experimental studies and has the potential to be a seminal contribution to the BD knowledge base relating to our understanding and accommodation of at-risk children having conduct disorders.

Analysis of Office Discipline Referrals as a Screening and Program Evaluation Tool

For the past decade a group of researchers at the University of Oregon have been investigating the metric of school discipline contacts or referrals to the principal’s office for student infractions(teacherdefiance,aggression,harassment,etc.)thatmerit more than just classroom-based sanctions (Sugai, Sprague, Horner, & Walker, 2000; Walker, Stieber, Ramsey, & O’Neill, 1993). Discipline referrals can be used to profile an entire school, small groups of students, and selected individual students within a school. Walker et al. (1993) found disciplinary referrals to be a powerful variable in discriminating lowrisk from high-risk antisocial students.Tobin and Sugai (1999) reported that discipline referrals are associated with the outcomes of identification for special education, restrictive placements, and later school dropout. Walker and McConnell (1995) found a moderately strong relationship between discipline contacts and later arrests in a longitudinal study of a sample of high-risk boys. Loeber and Farrington (1998) cited research showing a similar relationship of moderate strength between these two variables among antisocial youth.

In addition to profiling a school and selected students therein, aggregated discipline contacts across school years can be a sensitive measure of effective schoolwide interventions that address disciplinary issues (see Sprague, Sugai, Horner, & Walker, 1999). One of the clear advantages of this measure is that it accumulates as a natural by-product of the schooling process and can be culled unobtrusively from the existing archival student records of most schools. Currently, there is a need to establish normative databases on this measure at elementary, middle, and high school levels. In our view, this is a very promising measure that will prove attractive to BD researchers, scholars, and practitioners in the future. Readers should consult Wright and Dusek (1998) for a recent critique of the advantages and limitations of this measure.

Resistance to Intervention as a Tool for Determining Eligibility and Treatment Selection

A relatively new approach to making eligibility determinations and selecting or titrating interventions is based on the concept of resistance to intervention or, alternatively, lack of responsiveness to intervention. Gresham (1991) defined this concept as a student’s behavioral excesses, deficits, or situationallyinappropriate behaviors continuing at unacceptable levels subsequent to empirically supported interventions implemented with integrity. Resistance to intervention is based on the best practice of prereferral intervention and allows school personnel to function within an intervention context rather than a psychometric eligibility framework in identifying BD students.

Resistance to intervention results in a lack of change in target behaviors as a function of exposure to a proven intervention. This failure can be taken as partial evidence for a BD eligibility determination under auspices of the IDEA certification process. Moreover, this same concept can be used to modify, change, or titrate intervention procedures much like medications are titrated based on an individual’s responsiveness to a drug dosage or type. Third, resistance to intervention can be used as a cost-effective basis for allocating treatment resources to those students whose lack of responsiveness indicates that they need more intensive intervention.

A number of factors are related to resistance to intervention. Some of the factors that seem most relevant for school-based interventions are (a) severity of behavior, (b) chronicity of behavior, (c) the generalizability of behavior change, (d) treatment strength, (e) treatment integrity, and (f)treatmenteffectiveness.Allofthesefactorshavebeenidentified as being related to resistance of student behavior to intervention in past research (see Gresham, 1991, and Gresham & Lopez, 1996, for a discussion of these factors).

The notion of resistance to intervention provides BD professionals with a powerful method for managing schoolbased interventions in a cost-effective manner and for indirectly assessing the relative severity of a student’s problematic behavior. It stands as one of the most useful and valuable innovations in behavior disorders within the past decade.

This list of contributions by the BD field is selective and not representative in that it reflects our biased views. In addition, it by no means exhausts the universe of innovative contributions of the highest quality and impact in the BD field. A perusal of the BD peer-reviewed journals over the past few years documents many varied examples of outstanding achievements by BD scholars, researchers, and on-line professionals. These contributions have led to many enhancements in the life quality of students with behavior disorders and their families and have improved the skills and competence of those professionals who work with them. They provide solid evidence about what is right with the BD field (see Walker et al., 2000, for a more detailed discussion of these contributions).

What Is Wrong With Behavior Disorders?

No discipline can claim to be virtuous and above reproach in its policy, directions, and management of its professional agenda. That is certainly true of the BD field. However, it is important to note that there is much more right about BD than wrong with BD.

This section discusses some of the decisions, directional changes, and failures that have occurred within the BD field and that we believe have not served the field well. The following topics in this regard are discussed next: (a) the BD field’s failure to reference its interventions and achieved outcomes to societal issues and problems, (b) the adoption of a postmodern, deconstructivist perspective by some sectors of the BD field, (c) the failure to identify and serve the full range of K–12 students experiencing serious behavioral and emotional problems in the context of schooling, and (d) the lack of evidence of BD leadership in developing a prevention agenda for behaviorally at-risk students.

Referencing BD Interventions and Results to Societal Issues and Problems

Recently, Walker, Gresham, and their colleagues provided commentary on some shortcomings of the BD field and suggested some new directions for its consideration (see Walker et al., 1998). These authors made the following major points in this commentary:

- During the last several decades, the field of special education, of which BD is a subspecialty, has become politically radicalized and, unfortunately, fragmented as a result of internal strife and turf battles among professionals.

- Due in part to this disciplinary conflict, special education is often perceived by professionals in other fields as striferidden, expensive, litigious, consumed with legislative mandates, bound by court orders mandating certain practices, and ineffective.

- These external perceptions of special education have damaged its status and legitimacy, cast doubt on its ability to manage its affairs, and hindered its ability to pursue a professional agenda on behalf of individuals with disabilities and their families.

- Though largely avoiding this political strife, the BD field, by association, has suffered from these generic, pejorative impressions about special education that have been widely disseminated in the public media and through the professional networks of related disciplines.

Though regarded as controversial, this article has stimulated an ongoing debate in the BD field regarding the role of science in its activities, ways of knowing, and the legitimate domains of influence that the field should seek to develop. A central point of this commentary was that the BD field has a specialized and well-developed knowledge base, much of which is empirically verified and reasonably well integrated, that deals with the adjustment problems of at-risk, vulnerable children and youth in the context of schooling. However, as a matter of practice, the BD field does not take advantage of opportunities to demonstrate its contributions to solving problems of great societal concern (e.g., school failure and dropout, preventing gang membership, addressing bullying and harassment, preventing school violence, participating in delinquency prevention initiatives, ensuring school safety, and controlling the transport of dangerous weapons across school boundaries). Further, the BD field does not promote its solutions to these problems with the audiences that count, including the general public, state and local policy makers, and the U.S. Congress.

The article argued that the gap between what is known in the BD field and what is applied in everyday practice is glaring and likely rivals that of any other field. BD professionals were urged to reference the outcomes of their research to these larger issues of great societal concern and to target their interventions in ways that impact them and their precursors. In our view, the BD field has a long way to go in establishing its value to the larger constituencies that it serves as the fields of medicine, engineering, psychology, and speech-language pathology have accomplished so successfully. However, given the concerns of the public and educators about youth violence, schooling effectiveness, and school safety, the time has never been better for the BD field to demonstrate its value and effectiveness through the promotion of many of its seminal contributions as solutions to these societal problems.

Behavior Disorders and the Postmodern, Deconstructivist Perspective

Postmodernism and deconstructivist philosophies have spread rapidly through the social sciences in the past decade (Wilson, 1998). These philosophies reject the scientific method and deny the possibility of common or universal forms of knowledge. The proponents of postmodern deconstructivism (PD) often criticize scientific understanding on the basis that it is decontextualized and does not acknowledge the construction of meanings. PD advocates have gained considerable influence in many institutions of higher education; their positions pose a significant threat to the BD field partly because a behavior disorder or emotional disturbance is known as a judgmental disorder (Walker et al., 1998). That is, the disorder is said to exist only if certain persons agree that it represents a departure from expected or normative patterns of behavior. Thus, the subject matter of behavior disorders is particularly vulnerable to postmodern constructions of reality. PD suggests that we can know nothing but our own experiences and that the realities of phenomena are determined more by our perceptions of them than by their actual physical, objective attributes.

Postmodernism, as Kauffman has noted, is receiving considerable press and attention in the social sciences (Kauffman, 1999). Recently, the journal, Behavioral Disorders devoted a special issue to postmodern perspectives and formulations vis-à-vis behavior disorders (Hendrickson & Sasso, 1998). Reactions from BD scholar-researchers to the lead article by Elkind (1998) were not particularly supportive or in agreement with most of the key points made.

Elkind (1998), for example, argued that our conceptions and theories about behavior disorders are determined by the basic social and cultural tenets prevailing in our society at any given time. Elkind argued further that there has been a paradigm shift in this regard as reflected in the postmodern themes of difference, particularity, and regularity. Specifically, Elkind suggested that individual differences in behavioral characteristics and expression are so vast, complex, and unique that traditional classification systems are next to useless and artificial at best. Elkind recommended that we focus our efforts exclusively on the individual and said that BD professionals have at their disposal an array of therapeutic techniques, from differing theoretical approaches, and that we should apply combinations of them as the child’s individual needs warrant. How we would select such combinations of techniques and evaluate the efficacy of our efforts remains a mystery to the present authors.

Thiscase,albeitpersuasivelyarticulatedbyElkind,hasnot and likely will not be well received by the BD field. Calls to focus on the unique characteristics and strengths of individual children and youth have always had appeal for BD professionals. However, adoption of this approach by some sectors of the BD field strikes us as the inverse of progress. In our view, the wide spread adoption of this perspective would result in a return to a focus on the single case, each of which is considered a unique event, which characterized the early beginningsofthefieldofappliedbehavioranalysisover30years ago. Treating every student as a unique individual case means that we cannot generalize from one case to another and that each is essentially a new experiment, the results of which would have no meaning or relevance to those coming before or after. At present, we do not have the financial luxury of not treating at-risk students in group contexts within school settings.

Further, we have learned a great deal over the past two decades from studying problems and maladaptive conditions, among BD as well as non-BD student populations, that share certain commonalities of attributes and characteristics (e.g., ADHD, social isolation, instrumental aggression, antisocial behavior, depression, etc.). Our ability to develop interventions that produce similar outcomes, across children and youth representing these conditions, is critical to advancing the knowledge base in behavior disorders. It would be a mistake of gigantic proportions to abandon this approach in our research and development efforts in the future.

Ultimately, the postmodern perspective will likely occupy some space in the universe of accepted formulations about behavior disorders that currently exist in the BD field. However, because of the BD field’s long commitment to researchbased solutions and empirical approaches, we believe that it is doubtful that it will ever occupy a dominant or prevailing position in this regard.

Failure to Serve the Full K–12 Range of Students With Behavior Disorders

Historically, school systems have substantially underserved the K–12 student population with behavior disorders. As noted earlier, approximately 20% of the public school population is estimated to have serious mental health problems, but slightly less than 1% nationally of K–12 students are declared eligible annually for services under the ED category of the IDEA. Using the IDEA definition for ED, school psychologists have traditionally served as gatekeepers in determining which students referred for behavior disorders actually qualify as emotionally disturbed and thus are able to access the services, supports, and protections afforded through IDEA certification. School psychologists have typically used the IDEA definition for ED to rule out rather than rule in students referred for behavior disorders as emotionally disturbed; thus, the vast majority of students with schoolrelated mental health problems is denied access to IDEA services and appropriate interventions tailored to their needs. The ED definitional criteria of IDEA require that an evaluative judgment be made regarding whether the referred student is emotionally disturbed versus socially maladjusted. If as a result of the IDEA eligibility evaluation process the student is considered to be maladjusted, then ED certification is denied; otherwise, the student is certified and can access IDEA supports, services, and protections.

The strict gatekeeping by school psychologists around the determination of ED eligibility is reflective of school administrators’ extreme reluctance to extend the protections of IDEA to this student population. By so doing, it becomes very difficult to apply disciplinary sanctions to ED-certified students because of the protections built into IDEA. Furthermore, parents and advocates can sue school districts for not providing a free and appropriate education for an ED-certified student. Out-of-state residential placements for these students can easily exceed $100,000 annually, and school districts have to bear these costs if it is shown that they cannot provide a free, appropriate educational experience for an ED-certified student. Currently, the Hawaii state government is under a costly, court-ordered decree after losing a class action suit for denying services to ED-eligible students. Further, teachers who refer students with behavior disorders for possible ED certification are sometimes negatively regarded by administrators as unable to manage their classrooms effectively. In the face of these strong barriers, it is unlikely that adequately serving students with behavior disorders will ever be accomplished under the aegis of the IDEA.

The ED eligibility definition and its application to the population referred for behavior disorders has been the subject of considerable debate over the past several decades. It has been severely criticized as invalid and arbitrary (Forness & Knitzer, 1990; Gresham et al., 2000). Recently, Walker, Nishioka, Zeller, Bullis, and Sprague (2001) reported results of a study in which no differences were detected between 15 ED-certified and 15 noncertified socially maladjusted (SM) middle school boys on a series of measures that assessed both positive and negative forms of adjustment within home and school settings. The dimensions on which the two groups were evaluated included demographics, school history, academic achievement, social competence, behavioral characteristics, personal strengths, ADHD symptoms, and attitudes toward aggression and violence using multiple measures and informants across home and school settings (see Walker et al., 2001, for details of these measures). Given these results, it is difficult to see on what basis the judgment was made in determining the ED or SM status of these students. This is especially significant, given that 12 of the 15 socially maladjusted students had previously been referred and certified as eligible for special education but were later decertified. However, all of the socially maladjusted boys in this study had been placed on a waiting list for placement in an alternative middle school program for students having severe behavior problems.

The observation has been made by some BD professionals that students should not be screened and identified for services that do not currently exist. However, it is difficult to know how the true need for services for this population can be determined unless systematic screening efforts are put in place to document the extent of need. Without such careful documentation, motivations to develop services and delivery mechanisms will continue to be weak among school personnel. Standardized definitional criteria and screening procedures would likely be required to accomplish this goal.

We are convinced that a different approach is necessary to meet the needs of the public school student population with behavior disorders. In our view, an integrated approach or model of the type proposed by Walker et al. (1996) will be required to address the needs of all students in a school setting. This model provides for the seamless integration of differing types of interventions for achieving primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention goals and outcomes. In this integrated approach, universal interventions are used to achieve primary prevention outcomes; small-group interventions are used to address secondary prevention goals; and individualized interventions with wraparound services are used to address the needs of tertiary level students and their families. A resistance to intervention procedure determines which students require secondary and tertiary prevention supports and services following their exposure to the primary prevention intervention. This integrated model is highly cost-effective and is perhaps the only way that the mental health and adjustment needs of all students in today’s schools can be addressed, at some level, given the ongoing press on schooling dollars. A more detailed illustration of this model is presented in the section on evidence-based interventions.

BD Leadership in Developing a Prevention Agenda

In our view, there are two major opportunities or windows for mounting prevention initiatives that have a chance to divert behaviorally at-risk children from a destructive path. The two developmental periods or windows are the age ranges of 0 to 5 years and 6 to 10 years. Because BD professionals are primarily school based, they can have their greatest impact from kindergarten through the primary and intermediate grades. However, many behavioral specialists employed by school districts have the opportunity to work collaboratively with early childhood educators and Head Start personnel who deal with 3- and 4-year-olds. In the past decade there have been many anecdotal reports of very young children exhibiting more mature forms of destructive behavior (e.g., wearing gang colors, physically attacking teachers, plotting serious harm toward peers, engaging in inappropriate sexual behavior, etc.). Furthermore, larger numbers of children are coming to school lacking in specific school-readiness skills, and they are often very unprepared to cope with the normal demands and routines of schooling. In a recent survey Rimm-Kaufman, Pianta, and Cox (2000) documented the breadth and prevalence of school-readiness problems among kindergartners. In their survey, up to 46% of surveyed teachers reported that about half of their class entered kindergarten with problems in one or more areas, as follows: difficulty following directions, 46%; difficulty working independently, 34%; difficulty working as part of a group, 30%; problems with social skills, 20%; immaturity, 20%; and difficulty communicating/language problems, 14%. Longitudinal research indicates that these impairments in social competence and school readiness skills can serve as harbingers of future adjustment problems in a number of domains including interpersonal relations, employment, academic achievement, and mental health (Loeber & Farrington, 1998; McEvoy & Welker, 2000).

As noted earlier, increasing numbers of children are bringing antisocial, challenging behavior patterns with them to the schooling process. Moffitt (1994) referred to these children as early starters who are inadvertently socialized to an antisocial behavior pattern by their families and caregivers. Patterson et al. (1992) researched and illustrated the coercion processes operating among family members that lead to this unfortunate and destructive behavior pattern. In this family context, early starters learn to aggress, escalate, and coerce others to achieve their social goals. Most bring this behavior pattern with them to the schooling process, and this leads to social rejection by both teachers and peers within just a few years (Eddy et al., 2002). Unfortunately, a majority of these children will not access the school-based intervention supports and services that they need to succeed in school because of the practices of related services, school personnel who typically classify them as socially maladjusted which has the effect of denying them this access.

Thousands of our vulnerable children and youth are on a destructive path. The longer one remains on this path, the more serious are the outcomes the individual is likely to encounter. Longitudinal studies in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, and Western Europe converge in documenting this destructive pathway (Kellam, Brown, Rubin, & Ensminger, 1983; Loeber & Farrington, 1998; Patterson et al., 1992). Reid and his colleagues (Eddy, Reid, & Fetrow, 2000; Reid, 1993) have long argued that the earlier one addresses the problems of children who are on this path, the more likely it is that they will be successfully diverted from later destructive outcomes. Longitudinal follow-up studies of the long-term effects of early intervention provide clear evidence that this is indeed the case (see Barnett, 1985; Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott, & Hill; 1999; Strain & Timm, 2001). Further, in a randomized-control trial of early versus later intervention, Hawkins et al. (1999) found that a school-based early intervention that (a) targets and teaches social skills to students, behavior-management skills to teachers, and family-management skills to parents in a coordinated fashion; (b) facilitates bonding, engagement, and attachment to schooling; and (c) is delivered in the primary grades leads to strong protections against a number of healthrisk behaviors at age 18, including delinquent acts, teenage pregnancy, heavy drinking, multiple sex partners, behavioral incidents requiring disciplinary action at school, low achievement, and school failure.

It is essential that BD professionals assume a more active role, and a leadership one when possible, in making sure that all behaviorally at-risk children are detected at the point of school entry and provided with the supports, services, and interventions that will help ensure a successful beginning to their school careers. Achieving this goal will require developing close working relationships with early childhood educators, parents, and mental health professionals, where appropriate. The school-based BD professional is ideally positioned to assume this role and to coordinate the universal screening and intervention delivery strategies that can divert many behaviorally at-risk students from this path. More specifically, as argued elsewhere (Walker et al., 1999), we believe that the BD professional’s role should include the following functions at a minimum:

- Promulgating best practices for students both with and without behavior disorders that are research based and cost efficient.

- Advocating for educators’ adoption of proven evidencebased approaches to intervention.

- Forming true partnerships with general educators and professionals from other disciplines that create the commitment and breadth of knowledge necessary to address the complex needs and problems of the behaviorally at-risk school population.

- Taking the lead in building multidisciplinary, interagency team approaches to providing integrated interventions for at-risk students and their families.

The BD field has a talented and knowledgeable cadre of professionals who, in our estimation, could perform these functions skillfully. However, at present they are not adequately supported by school systems in performing these functions.

Adoption and Delivery of Evidence-Based Interventions

In traditional practice schools have not been strongly motivated to assume ownership and responsibility for solving the behavior problems and disorders of school-age children and youth. Rather than investing in proactive interventions to teach skills and to develop behavioral solutions, school administrators have relied primarily on a combination of sanctions (suspensions, expulsions) and assignment of problem studentstoself-containedsettingsinrespondingtotheBDstudent population. The basic strategy has been to punish or isolate students with challenging behavior rather than to solve their problems and respond to their needs. Some educators have referred to these students as the schools’homeless street people, and, in a very real sense, they have typically been treated as such.

In addition, school systems historically have not been motivated to search for and apply proven, cost-effective interventions that can substantively affect the learning and adjustment of the full range of K–12 students. Walker et al. (1998) noted that in no field is there a more glaring lack of connection between the availability of proven, research-based methods and their effective application by consumers in education. The analysis, commentary, and writings of Carnine (1993, 1995) and Kauffman (1996) have been instrumental in highlighting the gaps that exist in the field of education. Kauffman (1996) observed that the education profession is characterized by continuous change but little sustained improvement because the relationship between reliable, effective practices and their widespread adoption remains obscure. This is the dominant educational context in which BD professionals have to work and advocate for the adoption of proven, effective practices for the student population with behavior disorders.

However, in the last few years the attitudes of school systems have shown signs of change in this regard probably as a function of the twin pressures generated by the school reform movement and the school-shooting tragedies of the 1990s. Now schools are beginning to embrace the following practices, which had, in the past, been infrequently adopted: (a) the universal screening of all students to detect those with emerging behavior disorders; (b) investment in primary, secondary, and tertiary forms of prevention; (c) developing proactive rather than reactive responses to child and youth problems in school; and (d) searching for evidence-based interventions and approaches that are proven to work. This may be the front edge of a paradigm shift for the field of general education. If so, the school-based BD professional is ideally positioned to serve as a leader and resource in facilitating this organizational change.

In our view, the problems attendant on serving the full range of K–12 students with behavior disorders do not stem from a lack of available, evidence-based interventions. Rather, it is much more a problem of knowing what works, having the will to implement effective practices with good integrity, and finding the resources necessary to support this effort. A number of reviews of best practices in the areas of school-related behavior disorders, school safety, and violence prevention have been developed recently. These reviews provide a valuable resource for school-based professionals and administrators who often have difficulty locating and evaluating the efficacy of differing intervention models and approaches—all of which claim to be effective.

One of the most valuable, thorough, and comprehensive reviews of effective, school-based interventions addresses the effectiveness of programs for preventing mental disorders in school-age children and youth and that are designed for use primarily in school settings (Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 1999). These investigators reviewed the broad landscape of available programs numbering in the thousands.

It is instructive that they found only 34 evidence-based programs that met rigorous standards of efficacy. Their report provides the following valuable information for professional consumers:

- It identifies critical issues and themes in prevention research with school-age children and families.

- It profiles universal, selected, and indicated programs that reduce symptoms of both externalizing and internalizing symptoms.

- It summarizes state-of-the-art programs in the prevention of mental disorders in school-age children.

- It identifies the key elements that contribute to program success.

- It provides suggestions to improve the quality of program development and evaluation.

Aside from its overall quality, there are a number of specific strengths to the report of Greenberg et al. (1999). Separating the review into universal, selected, and indicated interventions and then determining whether the interventions reviewed address primarily externalizing or internalizing behavior problems and disorders substantially increases the relevance of the review for school applications and provides needed clarity for consumers. In our view, the great majority of adjustment problems that students manifest in the school setting are either directed outwardly toward the external social environment (i.e., aggression, defiance, bullying, coercion) or internally (i.e., social withdrawal, anxiety, depression, phobias) representing problems with others versus problems with self. Externalizing disorders usually require a reduce-and-replace intervention strategy, whereas internalizing disorders typically call for a focus on skill development and performance enhancement.

Greenberg et al. (1999) found that the most effective interventions were those that (a) had multiple components, (b) involved multiple social agents (parents, teachers, peers), (c) were implemented across several settings (classroom, playground, home), and (d) were in place for a sufficient period of time to register socially valid outcomes—usually a minimum of 1 year. This review is being continuously updated and expanded as new evidence-based interventions come on line. It is highly recommended as a blueprint or roadmap for BD professionals to use in upgrading schoolbased practices for the behaviorally at-risk K–12 population. A special issue of the APA journal Prevention and Treatment (March, 2001) was devoted to the report and its findings.

The U.S. Public Health Service classification system for differing types of prevention is well suited for the delivery of these three types of interventions profiled in the Greenberg et al. (1999) review (i.e., universal, selected, indicated). As a rule, universal interventions are used to achieve primary prevention goals and outcomes (i.e., to prevent harm); selected interventions are used for secondary prevention efforts (i.e., to reverse harm); and indicated interventions are used for tertiary prevention applications (i.e., to reduce harm). Walker et al. (1995, 1996) have adapted this classification schema for the delivery of proven interventions within school settings that address the needs of all students. Figure 20.3 illustrates this classification schema. School settings are ideally suited to implement this delivery structure because they are naturally organized to implement schoolwide interventions (e.g., a school discipline plan, a school safety plan, a school improvement plan), small-group interventions (e.g., resource and selfcontainedclassrooms),andindividuallytailoredinterventions (e.g., counseling). In the last 5 years, this three-level intervention delivery system has been widely adopted by researchers and school personnel alike across the country.

School personnel are especially amenable to universal intervention approaches because they treat all students equitably and in the same manner. Thus, the fairness issue that resonates so strongly with most teachers is indirectly addressed as every student is exposed to the intervention in an identical fashion. Those students for whom the universal intervention is insufficient then receive secondary and possibly tertiary prevention interventions. One of the great advantages of a universal intervention is that it creates a context in which more intensive small-group and individually tailored interventions can achieve greater effectiveness, which are then applied only after the failure of a universal intervention approach for certain students. Another is that it addresses the problems of mildly involved, at-risk students in a costeffective manner. The scaled-up adoption of this integrated delivery system, when combined with proven intervention models that have been adapted to and tested within the school setting, has the potential to improve substantially the effectiveness of schooling and to create much more positive school climates.

The Content of School Interventions for Students with Behavior Disorders

When children begin their school careers, they are required to make two critically important social-behavioral adjustments teacher-related and peer-related (Walker et al., 1995).That is, they must negotiate a satisfactory adjustment to the academic and behavioral expectations of teachers and conform to the demands of instructional settings. Of equal importance, they must negotiate a satisfactory adjustment to the peer group, find a niche within it, and develop social support networks consisting of friends, affiliates and acquaintances. Walker, Irvin, Noell, and Singer (1992) have developed an interpersonal model of social-behavioral competence for school settings. This model identifies the adaptive and maladaptive behavioral correlates of successful student adjustment in the domains of teacher-related and peer-related functioning. The model also describes the long-term outcomes that are commonly associated with the adaptive (e.g., school success, friendshipmaking, peer and teacher acceptance) versus maladaptive (e.g., school failure and dropout, assignment to restrictive settings, delinquency) pathways contained within it.

The adaptive and maladaptive behavioral correlates included in the teacher- and peer-related adjustment dimensions of this model are based on empirical evidence generated by the present authors and their colleagues as well as research evidence presented in the professional literature on social competence. The long-term outcomes listed for each path under these two forms of adjustment are based on longitudinal and cross-sectional studies reported in the literature over the past two decades (see Loeber & Farrington, 1998; Patterson et al., 1992; Strain, Guralnick, & Walker, 1986).

Failure in either of these critically important areas impairs a student’s overall school adjustment and success; failure in both puts a student’s overall quality of life at risk and is a harbinger of future problems of potentially severe magnitude. Students with behavior disorders are invariably below normative levels and expectations on the adaptive behavioral correlates of teacher- and peer-related adjustment and usually outside the normative range on the maladaptive behavioral correlates. In the great majority of cases, the intervention of choice for students with behavior disorders involves developing their social skills and overall social competence while teaching them alternatives to the maladaptive forms of behavior that tend to dominate their behavioral repertoires. In our view, the potential of social skills instruction (SSI) for students in general, and particularly for students with behavior disorders, has yet to be realized in spite of a substantial investment in SSI efforts over the past two decades by school personnel (Bullis, Walker, & Sprague, 2001; Elksnin & Elksnin, 1995).

Recent reviews of the efficacy of SSI with the K–12 school population with behavior disorders have not been encouraging (see Gresham, 1997, 1998a; Kavale, Mathur, Forness, Rutherford, & Quinn, 1997). These authors have conducted and reviewed meta-analyses of social skills interventions and concluded that the average effect sizes in the studies they reviewed are minimal to moderate at best, generally ranging between .30 and .45. Given the level of effort invested in these studies, these results do not appear to be terribly cost-effective. Anumber of reasons have been hypothesized for these disappointing outcomes, including (a) the failure to match deficits in social skills with the intervention, (b) the absence of theoretical models to guide SSI, (c) implementing the SSI procedure in artificial instructional settings and expecting generalization of newly taught skills to natural settings, and (d) implementing the SSI for insufficient amounts of time for it to impact the student’s behavioral repertoire. We belie vethat an equally powerful, but infrequently mentioned, reason concerns the failure to address the competing, maladaptive behavior problems of students with behavior disorders who are the targets of SSI. SSI alone is rarely sufficient to teach prosocial skills and simultaneously to address a well-developed maladaptive behavioral repertoire. Direct intervention techniques designed to reduce and eliminate maladaptive forms of behavior are required for this purpose. Some best-practice principles and guidelines for conducting SSI with students with behavior disorders are described next.

Social Skills Instruction for Students with Behavior Disorders

The school is an ideal setting for teaching social skills because of its accessibility to children and their peers, teachers, and parents. Fundamentally, social skills intervention takes place in school and home settings, both informally and formally, using either universal or selected intervention procedures. Informal social skills interventions are based on the notion of incidental learning, which takes advantage of naturally occurring behavioral incidents or events to teach appropriate social behavior. Most of the SSI in home, nonclassroom school contexts, and community settings can be characterized as informal or incidental. Literally thousands of behavioral incidents occur in these naturalistic home, school, and community settings, creating rich opportunities for making each of these behavioral incidents a potentially successful learning experience. Formal SSI, on the other hand, can take place seamlessly within a classroom setting in which (a) the social skills curriculum is exposed to the entire class or it is taught to selected students within small-group formats and (b) social skills are taught as subject matter in the same way as are social science, history, biology, and other academic subjects. However, unless formal and informal methods of teaching social skills are combined with each other, there is likely to be a disconnect between conceptual mastery of social skills and their demonstration and application within natural settings.

Objectives of Social Skills Instruction

SSI has four primary objectives: (a) promoting skill acquisition, (b) enhancing skill performance, (c) reducing or eliminating competing problem behaviors, and (d) facilitating generalization and maintenance of social skills. Most students with behavior disorders will likely have some combination of acquisition and performance deficits, some of which may be accompanied by competing problem behaviors. Any given student may require some combination of acquisition, performance,andbehavior-reductionstrategies.Allstudentswillrequire procedures to facilitate generalization and maintenance of previously learned social skills (see Gresham, 2002).

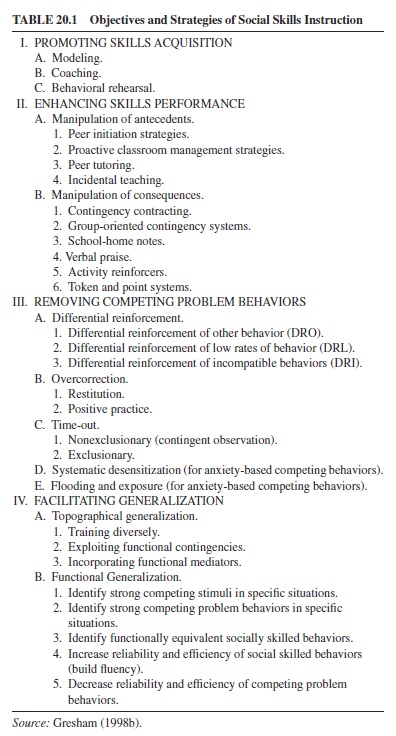

Table 20.1 lists specific social skills and behavior-reduction strategies for each of the four goals of SSI. Appropriate intervention strategies should be matched with the particular deficits or competing problem behaviors that the student exhibits. Acommon misconception is that one seeks to facilitate generalization and maintenance after implementing procedures for the acquisition and performance of social skills. The evidence is clear that the best and preferred practice is to incorporate generalization strategies from the beginning of any SSI program (Gresham, 1998b).

Promoting Skills Acquisition

Procedures designed to promote skill acquisition are applicable when students do not have a particular social skill in their repertoire, when they do not know a particular step in the performance of a behavioral sequence, or when their execution of the skill is awkward or ineffective (i.e., a fluency deficit). It should be noted that a relatively small percentage of students would need social skills intervention based on acquisition deficits; far more students have performance deficits (Gresham, 1998a).

Three procedures represent pathways to remediating deficits in social skill acquisition: modeling, coaching, and behavioral rehearsal. Social problem solving is another pathway, but it is not discussed here because of space limitations and because it incorporates a combination of modeling, coaching, and behavioral rehearsal. More specific information on social problem solving interventions can be found in Elias and Clabby (1992).

Modeling is the process of learning a behavior by observing another person performing it. Modeling instruction presents the entire sequence of behaviors involved in a particular social skill and teaches the student how to integrate specific behaviors into a composite behavior pattern. Modeling is one of the most effective and efficient ways of teaching social behavior (Elliott & Gresham, 1992; Schneider, 1992).

Coaching is the use of verbal instruction to teach social skills. Unlike modeling, which emphasizes visual displays of social skills, coaching utilizes a student’s receptive language skills. Coaching is accomplished in three fundamental steps: (a) presenting social concepts or rules, (b) providing opportunities for practice or rehearsal, and (c) providing specific informational feedback on the quality of behavioral performances.

Behavioral rehearsal refers to practicing a newly learned behavior in a structured, protective situation of role-playing. In this way, students can enhance their proficiency in using social skills without experiencing adverse consequences. Behavioral rehearsal can be covert, verbal, or overt. Covert rehearsal involves students’ imagining certain social interactions (e.g., being teased by another student or group of students). Verbal rehearsal involves students’ verbalizing the specific behaviors that they would exhibit in a social situation. Overt rehearsal is the actual role-playing of a specific social interaction.

Enhancing Skills Performance