View sample relationships between teachers and children research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Relationships between teachers and children have been a focus of educators’concerns for decades, although this attention had taken different forms and had been expressed using a wide range of constructs and paradigms. Over many years, diverse literatures attended to teachers’and students’expectations of one another, discipline and class management, teaching and learning as socially mediated, teachers’own self- and efficacy-related feelings and beliefs, school belonging and caring, teacher-student interactions, and the more recent attention to teacher support as a source of resilience for children at risk (e.g., Battistich, Solomon, Watson, & Schaps, 1997; Brophy & Good, 1986; Eccles & Roeser, 1998). In many ways, these literatures provided the conceptual and scientific grounding for the present focus on child-teacher relationships, and in turn, a focus on relationships provides a mechanism for integrating these diverse literatures into a more common language and focus. In fact, one of the goals of this research paper is to advance theory and research in these many areas by changing the unit of analysis and focus to relationships between teachers and children. This new framework has potential for integrating what,up to this point, has been a large array of findings involving how teachers and students relate to one another that has been spread among sources and outlets that often have little contact and overlap. This integrative, crosscutting perspective, utilizing the more holistic, molar unit of analysis of relationship, is consistent with modern views of human development in which the developmental process is viewed as a function of dynamic, multilevel, reciprocal interactions involving person and contexts (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Lerner, 1998; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998).

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

It is the broad aim of this research paper to summarize historic trends in the emergence of research on child-teacher relationships and to further advance theoretical and applied efforts by organizing the available work on child-teacher relationships currently residing across diverse areas of psychology and education.

Child-Teacher Relationships: Historical Perspectives and Intersections

Relationships, detailed in a subsequent section, involve many component entities and processes integrated within a dynamic system (Hinde, 1987; Magnusson & Stattin, 1998). Components include expectations, beliefs about the self or other, affects, and interactions, to identify a few (Eccles & Roeser, 1998; Pianta, 1999; Sroufe, 1989a; Stern, 1989). In a school or classroom setting, each of these components has its own extensive literature, for example, on teacher expectations or the role of social processes as mediators of instruction (see Eccles & Roeser, 1998). Therefore, the study of child-teacher relationships traces its roots to many sources in psychology and education.

Educational psychology, curriculum and instruction, and teacher education each provide rich sources of intellectual nourishment for the study of relationships between teachers and children. From a historical perspective, early in Dewey’s writing (Dewey, 1902/1990) and in texts by Vygotsky (e.g., 1978), there are frequent Bibliography: to relationships between teachers and children. Social relations, particularly a sense of being cared for, were considered an important component in Dewey’s conceptualization of the school as a context, and certainly Vygotsky’s emphasis on support provided to the child in the context of performing and learning challenging tasks was a central feature of his concept of the zone of proximal development.

Based on the exceptionally detailed descriptions of human activity and interaction undertaken by Barker and colleagues (see Barker, 1968), extensive observational research on classroom interactions involving teachers and children was conducted, with refinement and further development of methods and concepts culminating in the foundation studies on childteacher interactions by Brophy and Good (1974).

Somewhat parallel to the focus of Brophy and Good on classroom interactions was the emergence of the broad literatures on interpersonal perception that took form in research on attribution and expectation, notably studies by Rosenthal (1969) on the influence of expectations on student performance. These studies strongly indicated that instruction is something more than simply demonstration, modeling, and reinforcement, but instead a complex, socially and psychologically mediated process. Work on student motivation, selfperceptions, and goal attainment has documented strong associations between these child outcomes and school contexts, including teachers’ attitudes and behaviors toward the child (see Eccles & Roeser, 1998). More recently, research and theory on the concept of students’ help-seeking behavior (Nelson-Le Gall & Resnick, 1998; Newman, 2000) actively addresses the integration of emotions, perceptions, and motivations in the context of instructional interactions, pointing again to the importance of the relational context created for the child.

At the same time, there has always been anecdotal and case study evidence for child-teacher relationships in the clinical psychology and teacher training literatures. These anecdotes typically describe how a child’s relationship with a particular teacher was instrumental in somehow rescuing or saving that child and placing the child on the path to success and competence in life (e.g., Pederson, Faucher, & Eaton, 1978; Werner & Smith, 1980). Such stories often provide compelling evidence for attempts to harness the potential of these relationships as resources for children.

Developmental psychology and its applied branches related to prevention provide considerable conceptual and methodological underpinnings to the study of child-teacher relationships (see Pianta, 1999). The study of human development has contributed a scientific paradigm for studying relationships, conceptual models that advance ideas about how contexts and human development are linked with one another, and scores of studies demonstrating the value of relationships for human development in other arenas (see Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998).

In part because of the extensive and long-standing empirical and theoretical work on marital and parent-child relationships, core conceptual and methodological frameworks and concepts for understanding and studying interpersonal relationships have emerged (Bakeman & Gottman, 1986; Bornstein, 1995). These scientific tools form a foundation, or infrastructure, that can be applied to the study of children and teachers (e.g., Howes, Hamilton, & Matheson, 1994; Pianta & Nimetz, 1991). Clearly, the work of Bowlby (1969), Ainsworth (e.g., Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), and Sroufe (1983; Sroufe & Fleeson, 1988) on attachment between children and parents provides some of the strongest theoretical and empirical support for the influence of relationships between children and adults on child development. It was largely the concentrated focus on understanding child-mother attachment that helped to advance the idea of child-adult relationships as systems and to identify the component processes and mechanisms.

In addition to work on child-parent attachment, developmental psychologists were involved in research on early intervention and day care experiences as they contribute to child development, which identified relational or interactional aspects of those settings (e.g., quality of care and caregiver sensitivity) that were related to child outcomes (Howes, 1999, 2000a). Furthermore, this line of inquiry also described how structural aspects of settings (e.g., child-teacher ratios and teacher training and education) contributed to the social and emotional quality of interactions between child and teacher (see NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [NICHD ECCRN], 2002). Developmental methodologists interested in child-parent interactions, peer, and marital interactions as well as those working from a comparative or ethological framework contributed substantially to the study of child-teacher relationships by describing the functions and processes of relationships (Bakeman & Gottman, 1986; Hinde, 1987). Finally, recent work on motivation and the development of the child’s sense of self and identity provides compelling evidence that teachers are an important source of information and input to these processes (Eccles & Roeser, 1998).

Over the last two decades, as developmental psychology, school psychology, and clinical psychology have formed convergent interests (Pianta, 1999) and as the more integrative paradigm of developmental psychopathology emerged (Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995), relationships between children and adults have received much attention as a resource that can be targeted and harnessed in prevention efforts. Paradigms for prevention and early intervention in the home environment, as well as intervention approaches focusing on parent-child dyads in which the child demonstrates serious levels of problem behavior (e.g., Barkley, 1987; Eyberg & Boggs, 1998), have focused on improving the quality of child-parent relationships. That work has resulted in a fairly large body of knowledge concerning how relationships can be changed through intentional focus on interactions, perceptions, and interactive skills (Eyberg & Boggs, 1998). These studies have provided a strong basis for extensions into school settings (McIntosh, Rizza, & Bliss, 2000; Pianta, 1999).

In more recent years the focus on prevention that has arisen from this nexus of overlapping interests among scientists, policy makers, and practitioners has viewed school settings as a primary locus for the delivery and infusion of resources that have a preventive or competence-enhancing effect (Battistich et al., 1997; Cowen, 1999; Durlak & Wells, 1997). Schoolbased mental health services, delivery of a range of associated services in full-service schools, reforms aimed at curriculum and school management, and issues related to school design and construction frequently identify child-teacher relationships as a target of their efforts under the premise that improving and strengthening this school-based relational resource can have a dramatic influence on children’s outcomes (see Adelman, 1996; Battistich et al., 1997; Durlak & Wells, 1997; Haynes, 1998). Finally, it has also been suggested that one by-product of such efforts to enhance relationships between teachers and children is an improvement in teachers’ own mental health, job satisfaction, and sense of efficacy (e.g., Battsitich et al., 1997; Pianta, 1999).

Although diverse areas of psychology address issues related to relationships between teachers and children, extending back in time nearly 80 years, the study of childteacher relationships has not, until the last decade, been an area of inquiry unto itself. This lack of focus has been due to the widely scattered nature of its intellectual roots and a tendency toward insularity among disciplines, problems with the use of different terminology and languages, seams between research and practice and between psychology in education and psychology in the family or laboratory, and the lack of theoretical models that adequately emphasize the role of multiple contexts in the development of children over the life span (Lerner, 1998). Perhaps one of the strongest conceptual advances contributing to the last decade of work on child-teacher relationships has been the developmental psychopathology paradigm, with its emphasis on integration across diverse theoretical frameworks and its embrace of a developmental systems model of contexts and persons in time (see Cicchetti & Cohen, 1995).

The present focus on child-teacher relationships reflects this integration and interweaving of theoretical traditions, methodologies, and applications across diverse fields. This area of inquiry, understanding, and application is inherently interdisciplinary. Yet the organizing frame for such work— although different areas have evolved from different traditions—is best found in current models of child development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Cairns & Cairns, 1994; Lerner, 1998; Magnusson & Stattin 1998; Sameroff, 1995). In these models, development of the person in context is depicted as a function of dynamic processes embedded in multilevel interactions between person and contexts over time. Developmental systems theory (Lerner, 1998) forms the core of an analysis of child-teacher relationships.

Developmental Systems Theory

In the last two decades, views that embrace the perspective that the study of development is in large part the study of living systems and is therefore informed by the study of systems have been adopted as the primary conceptual paradigm in human development (see Lerner, 1998, for example). As noted by Lerner (1998), “a developmental systems perspective is an overarching conceptual framework associated with contemporary theoretical models in the field of human development” (p. 2). General systems theory has a long history in the understanding of biological, ecological, and other complex living systems (e.g., Ford & Ford, 1987; Ford & Lerner, 1992) and has been applied to child development by Ford and Lerner (1992) and Sameroff (1995) in what is called developmental systems theory (DST). DST can be applied to the broad array of systems involved in the practice of psychology with children and adolescents (Pianta, 1999). The principles of DST help integrate analysis of the multiple factors that influence young children, such as families, communities, social processes, cognitive development, schools, teachers, peers, or conditions such as poverty. This analysis of child-teacher relationships draws heavily on developmental systems perspectives for principles and constructs that guide inquiry, understanding, and integration of diverse knowledge sources.

For the purposes of this discussion, systems are defined as units composed of sets of interrelated parts that act in organized, interdependent ways to promote the adaptation and survival of the whole. Families, classrooms, child-parent and child-teacher relationships, self-regulatory behaviors, and peer groups are systems of one form or another, as are various biologic systems within the organism. These systems function at a range of levels in relation to the child—some distal and some more proximal (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). They are involved in multiple forms of activity involving interactions within levels and across levels (Gottlieb, 1991) that form a pattern, or matrix, of reciprocal, bidirectional interactions that varies with time. In the case of child-teacher relationships, this perspective is reflected in analysis of the ways that school policies about child-teacher ratios affect student-teacher interactions that in turn are related to students’ and teachers’perceptions and affects toward one another. It is important to note that one must recognize the vertical as well as lateral interactions across and within levels and associated systems. The concept of within- and across-level interactions among systems is a key aspect of DST as applied to childteacher relationships; for example, just as these relationships are influenced by the interactions of two individuals, they are in turn affected (and affect) classroom organization and climate.

Principles Influencing the Behavior and Analysis of Developmental Systems

The behavior of developmental systems is best understood in the context of a number of general principles. These principles apply across all forms of living systems (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998).

Holism and Units of Analysis

Because of the preponderance of rich, cross-level interactions, interpretation and study of the behavior of systems at any level must take place in the context of activity at these other levels. Behavior of a “smaller” system (e.g., children’s self-regulation in a classroom) should be understood in relation to its function in the context of systems at more distal levels (e.g., child-teacher relationships) as well as more proximal or micro levels (e.g., biological systems regulating temperament) and vice versa. The rich, reciprocal interconnections among these units promote the idea that a relational unit of analysis is required for analysis of development (Lerner, 1998). From this perspective, noted Lerner (1998), the causes of development are relationships among systems and their components, not actions in isolation. This is highly similar to the perspective advanced by Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998), who argued that the primary engine of development is proximal process—interactions that take place between the child and contexts over extended periods of time. Bronfenbrenner and Morris cited interactions with teachers as one course of proximal process. For several developmental theorists, acknowledging the existence of multilevel interactions leads directly to the need for research that has these interactions and relationships as their foci.

Magnusson and Stattin (1998) approached the issue of holism from a somewhat different perspective. They noted that most psychological (and educational) research and theory are variable-focused—that is, a construct of interest is the sole focus of measurement and inquiry, inasmuch as variation in that construct relates to other sources of variation. This approach, argued Magnusson and Stattin, yields a science that examines selective aspects of the person but misses large sectors of experience that may hold descriptive and explanatory power. Behavior is better viewed in terms of higher order organized patterns of relations across different components of the system.

The developing child is also a system. From this point of view, motor, cognitive, social, and emotional development are not independent entities on parallel paths but are integrated within organized, dynamic processes. Psychological practices (assessment or intervention) that focus solely on one of these domains (e.g., cognition, personality, attention span, aggression, or reading achievement) can reinforce the notion that developmental domains can be isolated from one another and from the context in which they are embedded. Taking a developmental systems perspective, many argue that child assessment should focus on broad indexes reflecting integrated functions across a number of behavioral domains as they are observed in context (e.g., Greenspan & Greenspan, 1991; Sroufe, 1989b). Terms such as adaptation have been used to capture these broad qualities of behavioral organization, and although fairly abstract, they call attention to a focus on how children use the range of resources available to them (including their own skills and the resources of peers, adults, and material resources) to respond to internal and external demands.

In terms of this analysis of child-teacher relationships, holism means that to understand the discipline-related behavior of a teachers in their classrooms, one must know something about the school, school system, and community in which the teachers are embedded, their experiences, and their own internal systems of cognition and affect regulation in relation to behavioral expectations in the classroom. From the perspective of holism, the whole (i.e., the pattern or organization of interconnections) gives meaning to the activity of the parts (Sameroff, 1995).

Reciprocal, Functional Relations Between Parts and Wholes

Systems and their component entities are embedded within other systems. Interactions take place within levels (e.g., beliefs about children affect a teachers’beliefs about a particular child; Brophy, 1985) and across levels (e.g., teachers’beliefs about children are related to their training as well as to the school in which they work; Battstitch et al., 1997) over time. It is a fundamental tenet of developmental systems theories that these interactions are reciprocal and bidirectional. Gottlieb (1991) refered to these interactions as coactivity in part to call attention to the mutuality and reciprocity of these relations. Similarly, Magnusson and Stattin (1998) and Sameroff (1995) emphasized that in multilevel, dynamic, active, moving systems, it is largely fictional to conceptualize “cause” or “source” of interactions and activity. Again, this view has consequences for considerations of child-teacher relationships when examining the large number of components of these relationships as well as the multilevel systems in which they are embedded (Eccles & Roeser, 1998).

Motivation and Change

Systems theory offers alternative views of the locus of motivation and change. Within behavioral perspectives, change and motivation to change are often viewed as derived extrinsically—from being acted on by positive (or negative) reinforcement, or reinforcement history. Maturationist or biological views of change posit that the locus of change resides in the unfolding of genetic programs, or chronological age. From both perspectives the child is a somewhat passive participant in change—change is something that happens to the child, whether from within or without.

In developmental systems theory the motivation to change is an intrinsic property of a system, inherent in that system’s activity. Developmental change follows naturally as a consequence of the activity of interacting systems. That children are active can be seen in the ways they continually construct meaning, seek novelty and challenges, or practice emergent capacities. Furthermore, the child acts within contexts that are dynamic and fluid. Motivation, or the desire to change, is derived from the coaction of systems—of child and context (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). That relationships play a fundamental role as contexts for coaction between child and the world is supported by Csikszentmihalyi and Rathunde’s (1998) proposition that relationships with parents are foundational for establishing the rhythm of interaction between the child and the external world.

Maturationist or biological views of the motivation for developmental change tend to rely on characteristics of the child as triggers for developmental experience and can result in practices and policies that neglect individual variation or notions of adaptation. Strongly behavioral views of motivation focus solely on contingencies while failing to acknowledge the meaning of target behaviors and contextual responses to the child’s goals, leading to a disjunction between how the child perceives his or her fit in the world and how helpers may be attempting to facilitate change. Views of motivation informed by systems theory lead to a developmental interactionism (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998) that focuses attention on issues of goodness of fit, relationships, and related relational constructs. As Lerner (1998) acknowledged, because of relationism, an attribute of the organism has meaning for psychological development only by virtue of its timing of interaction with contexts or levels.

Developmental change occurs when systems reorganize and transform under pressure to adapt. Development takes place, according to Bronfenbrenner and Morris (1998), through progressively more complex reciprocal interactions. Change is not simply a function of acquiring skills but a reorganization of skills and competencies in response to internal and external challenges and demands that yields novelty in emergent structures and processes (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998).

Competence as a Distributed Property

Children, as active systems, interact with contexts, exchanging information, material, energy, and activity (Ford & Ford, 1987). Within schools, teacher and children engage within a context of multilevel interactions involving culture, policy, and biological processes (Pianta & Walsh, 1996). The dynamic, multilevel interactionism embodied in the principle of holism also suggests that children’s competence is so intertwined with properties of contexts that properties residing in the child (e.g., cognition, attention, social competence, problem behaviors) are actually distributed across the child and contexts (e.g., Campbell, 1994; Hofer, 1994; Resnick, 1994). Cognitive processes related to attending, comprehending, and reasoning (Resnick, 1994); emotion-related processes such as emotion regulation and self-control; helpseeking; and social processes such as cooperation are all properties not of the child but of relations and interactions of the child in the context of the classroom: They reflect a certain level of organization and function (Magnusson & Stattin, 1998).

The concept of affordance (see Pianta, 1999, for an explanation of this construct as applied to classrooms) embodies the idea that contexts contain resources for the child that can be activated to sustain the child’s adaptation to the demands of that setting. It is important to note that the affordance of a context must be accessed by interactions with the child. From the perspective of developmental systems theory, competence (and problems) in a classroom setting cannot be conceptualized or assessed separately from attributes of the setting and the interactions that features of the child have with those setting attributes (and in turn how these interactions are embedded in larger loops of interaction). At the level of social and instructional behavior between teachers and children, understanding these interactions may require a moment-by-moment analysis of behavioral loops, whereas understanding how the teacher’s behavior in these loops is a function of her education and training may require a much wider time frame (Pianta, La Paro, Payne, Cox, & Bradley, 2002). The coordination of these temporal cycles of interaction within and across levels is critical to understanding behavior within the specific setting of interest.

Centrality of Relationships in Human Development

In the context of all these multilevel and multisystem interactions, enduring patterns of interaction between children and adults (i.e., relationships) are the primary conduit through which the child gains access to developmental resources. These interactions, as noted earlier, are the primary engine of developmental change. Relationships with adults are like the keystone or linchpin of development; they are in large part responsible for developmental success under conditions of risk and—more often than not—transmit those risk conditions to the child (Pianta, 1999).

Our focus here is primarily on school-age children and their relationships with teachers in classroom settings. There is virtually no question that relationships between children and adults (both teachers and parents) play a prominent role in the development of competencies in the preschool, elementary, and middle-school years (Birch & Ladd, 1996; Pianta & Walsh, 1996; Wentzel, 1996). They form the developmental infrastructure on which later school experiences build. Childadult relationships also play an important role in adaptation of the child within the context in which that relationship resides—home or classroom (e.g., Howes, 2000b; Howes, Hamilton, et al., 1994; Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994). The key qualities of these relationships appear to be related to the ability or skill of the adult to read the child’s emotional and social signals accurately, respond contingently based on these signals (e.g., to follow the child’s lead), convey acceptance and emotional warmth, offer assistance as necessary, model regulated behavior, and enact appropriate structures and limits for the child’s behavior. These qualities determine that relationship’s affordance value.

Relationships with parents influence a range of competencies in classroom contexts (Belsky & MacKinnon, 1994; Elicker, Egeland, & Sroufe, 1992; LaFreniere & Sroufe, 1985; Pianta & Harbers, 1996; Sroufe, 1983). Research has established the importance of child-parent (often childmother) relationships in the prediction and development of behavior problems (Campbell, 1990; Egeland, Pianta, & O’Brien, 1993), peer competencies (Elicker et al., 1992; Howes, Hamilton, et al., 1994), academic achievement, and classroom adjustment (Pianta & Harbers, 1996; Pianta, Smith, & Reeve, 1991). Consistent with the developmental systems model, various forms of adaptation in childhood are in part a function of the quality of child-parent relationships.

For example, a large number of studies demonstrate the importance of various parameters of child-parent interaction in the prediction of a range of academic competencies in the early school years (e.g., de Ruiter & van IJzendoorn, 1993; Pianta & Harbers, 1996; Pianta et al., 1991; Rogoff, 1990). These relations between mother-child interaction and children’s competence in mastering classroom academic tasks reflect the extent to which basic task-related skills such as attention, conceptual development, communication skills, and reasoning emerge from, and remain embedded within, a matrix of interactions with caregivers and other adults. Furthermore, in the context of these interactions children acquire the capacity to approach tasks in an organized, confident manner, to seek help when needed, and to use help appropriately.

Qualities of the mother-child relationship also affect the quality of the relationship that a child forms with a teacher. In one study, teachers characterized children with ambivalent attachments as needy and displayed high levels of nurturance and tolerance for immaturity toward them, whereas their anger was directed almost exclusively at children with histories of avoidant attachment (Motti, 1986). These findings are consistent with results in which maltreated and nonmaltreated children’s perceptions of their relationships with mothers were related to their need for closeness with their teacher (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1992), as well as to the teachers’ ratings of child adjustment (Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). Cohn (1990) found that boys classified as insecurely attached to their mothers were rated by teachers as less competent and more of a behavior problem than were boys classified as securely attached. In addition, teachers reported that they liked these boys less. This link between the quality of child-parent relationships and the relationship that a child forms with a teacher confirms Bowlby’s (1969) contention that the mother-child relationship establishes for the child a set of internal guides for interacting with adults that may be carried forward into subsequent relationships and affect behavior in those relationships (Sroufe, 1983). These representations can affect the child’s perceptions of the teacher (Lynch & Cicchetti, 1992), the child’s behavior toward the teacher and the teacher’s behavior toward the child (Motti, 1986), and the teacher’s perceptions of the child (Pianta, 1992; Toth & Cicchetti, 1996). On the other hand, there are limits to concordance and stability in mother-child and teacher-child relationships as children move from preschool to school (Howes, Hamilton, & Phillipsen, 1998).

In sum, there is no shortage of evidence to support the view that—particularly for younger children, but also for children in the middle and high school years—relationships with adults are indeed involved centrally in the development of increasingly complex levels of organizing one’s interactions and relationships with the world. In this view, adultchild relationships are a cornerstone of development, and from a systems perspective intervention involves the intentional structuring or harnessing of developmental resources (such as adult-child relationships) or the skilled use of this context to developmental advantage (Lieberman, 1992). This is inherently a prevention-oriented view (Henggeler, 1994; Roberts, 1996) that depends on professionals’ understanding the mechanisms responsible for altering developmental pathways and emulating (or enhancing) these influences in preventive interventions (e.g., Hughes, 1992; Lieberman, 1992).

In conclusion, a developmental systems perspective draws attention to this child as an active, self-motivated organism whose developmental progress depends in large part on qualities of interactions established and maintained over time with key adult figures. Such interactions, and their effects, are best understood using child-adult relationships as the unit of analysis and then embedding this focus on relationships within the multilevel interactions that impinge on and are affected by this relationship from various directions.

Conceptual-Theoretical Issues in Research on Child-Teacher Relationships

This section updates and extends Pianta’s (1999) model of relationships between children and teachers and reviews research related to components of this model. The model is offered as an integrative heuristic. It draws heavily on principles and concepts of systems theory, positing that by focusing at the level of relationships as the unit of analysis, significant advances can be made in understanding the development of child-teacher relationships and in their significance in relation to child outcomes. Considering the wide-ranging and diverse literatures that currently address, in some form or another, the multiple systems that interact with and comprise child-teacher relationships, a model of such relationships needs to be integrative. As suggested by the examples used in the previous discussion of developmental systems theory, this model must incorporate aspects of children (e.g., age or gender), teachers (experience, efficacy), teacher-child interactions (discipline, instruction), activity settings, children’s and teachers’ perceptions and beliefs about one another, and school policy (ratios) and climate (Battistich et al., 1997; Brophy, 1985; Brophy & Good, 1974; Eccles & Roeser, 1998).

It is our firm belief that greater understanding of the developmental significance of school settings can be achieved by this focus on child-teacher relationships as a central, core system involved in transmitting the influence of those settings to children. Narrow-focused examinations of one or two of the factors just noted, as they relate in bivariate fashion to one another, are unlikely to yield a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic, multilevel interactions that take place in schools, the complexities of which have frustrated educational researchers and policy makers for years (Haynes, 1998). In many ways, a focus on the system of child-teacher relationships as a key unit of analysis may provide the kind of integrative conceptual tool for understanding development in school settings that a similar focus on parent-child relationships provided in the understanding of development in family settings (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Pianta, 1999).

Hinde (1987) and others (e.g., Sameroff, 1995) describe relationships as dyadic systems. As such, relationships are subject to the principles of systems behavior described earlier; they are dynamic, multicomponent entities involved in reciprocal interactions across and within multiple levels of organization and influence (Lerner, 1998). They are best considered as abstractions that represent a level or form of organization within a much larger matrix of systems and interactions. The utility of a focus at this level of analysis is borne out by ample evidence from the parent-child literature as well as studies examining children and teachers using this relational focus (Howes, 2000a). For example, when the focus of teachers’ reports about children is relational rather than simply a focus on the child’s behavior, it is the relational aspects of teachers’ views that are more predictive of longterm educational outcomes compared with their reports about children’s classroom behavior (Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Evidence also suggests that teachers’ reflections on their own relational histories, as well as current relationships with children, relate to their behavior with and attitudes toward the child more than do teacher attributes such as training or education (Stuhlman & Pianta, in press). Coming to view the disparate and multiple foci of most research on teachers and children using the lens or unit of child-teacher relationships appears to provide considerable gain in understanding the complex phenomenon of classroom adjustment.

A relationship between a teacher and child is not equivalent to only their interactions with one another, or to their characteristics as individuals.Arelationship between a teacher and a child is not wholly determined by that child’s temperament, intelligence, or communication skills. Nor can their relationship be reduced to the pattern of reinforcement between them. Relationships have their own identities apart from the features of interactions or individuals (Sroufe, 1989a).

A Conceptual Model of Child-Teacher Relationships

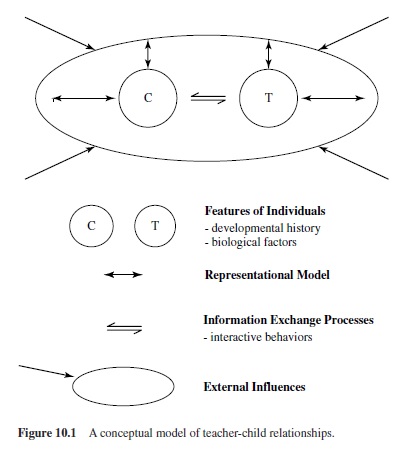

A conceptual model of child-teacher relationships is presented in Figure 10.1. As depicted in Figure 10.1, the primary components of relationships between teachers and children are (a) features of the two individuals themselves, (b) each individual’s representation of the relationship, (c) processes by which information is exchanged between the relational partners, and (d) external influences of the systems in which the relationship is embedded. Relationships embody features of the individuals involved. These features include biologically predisposed characteristics (e.g., temperament), personality, self-perceptions and beliefs, developmental history, and attributes such as gender or age. Relationships also involve each participant’s views of the relationship and the roles of each in the relationship—what Bowlby (1969) and Sroufe and Fleeson (1988) called the members’representation of the relationship. Consistent with evidence from the literature on parent-child relationships (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985; Sroufe & Fleeson; 1986), representational models are conceptualized not as features of individuals but as a higher order construct that embodies properties of the relationship that are accessed through the participants. Note that this is an advance from the model presented by Pianta (1999) in that the current model places more emphasis on the partners’ representations of the relationship as distinct from characteristics of the individuals.

Relationships also include processes that exchange information between the two individuals and serve a feedback function in the relationship system (Lerner, 1998).These processes include behavioral interactions, language, and communication. These feedback, or information exchange, processes are critical to the smooth functioning of the relationship. It is important to recognize that these relationship components (individual characteristics, representational models, information exchange processes) are themselves in dynamic, reciprocal interactions, such that behaviors of teacher and child toward one another influence representations (Stuhlman & Pianta, in press), and attributes of the child or teacher are related to teachers’ perceptions of the relationship (Saft & Pianta, 2001) or interactive behaviors (Pianta et al., 2002).

In turn, these relationship systems are embedded in many other systems (schools, classrooms, communities) and interact with systems at similar levels (e.g., families and peer groups). Finally, it is important to emphasize that adult-child relationships embody certain asymmetries. That is, there are differential levels of responsibility for interaction and quality that are a function of the discrepancy in roles and maturity of the adult and child, the balance of which changes across the school-age years (Eccles & Roeser, 1998).

Features of Individuals in Relationships

At the most basic level, relationships incorporate features of individuals. These include biological facts (e.g., gender) and biological processes (e.g., temperament, genetics, responsivity to stressors) as well as developed features such as personality, self-esteem, or intelligence. In this way developmental history affects the interactions with others and, in turn, influences relationships (Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991; Zeanah et al., 1993). For example, a teacher’s history of being cared for can be related to how he or she understands the goals of teaching and, in turn, can relate to the way he or she interprets and attends to a child’s emotional behavior and cues (Zeanah et al., 1993).

Characteristics of Teachers

In contrast to what is known about parents in relation to their interactions with children, virtually nothing is known about teachers. Despite a general recognition that teacher characteristics and perceptions influence the practice of teaching, little is known about how individual teacher characteristics and perceptions impact the formation of their relationships with children. Some have suggested that due to the importance of the social climate of the classroom, teaching may require more personal involvement than most other professions:

The act of teaching requires teachers to use their personality to project themselves in particular roles and to establish relationships within the classroom so that children’s interest is maintained and a productive working environment is developed. The teacher relies on his personality and his ability to form relationships in order to manage the class and ensure smooth running. (Calderhead, 1996, p. 720)

When questioned about their relationships with teachers, children acknowledge that teachers’ abilities to access this more personal part of themselves is an important component of creating a feeling of caring between teachers and children (Baker, 1999). By providing emotional support and asking children about their lives, teachers may enable children to feel more comfortable and supported in the school environment.

Teachers, like all adults, vary in their ability and desire to become personally involved in their work. In a series of case studies logging the thoughts of several student teachers over the course of training, Calderhead and Robson (1991) discussed teachers’ images of themselves as educators and provided examples of several very different perspectives on what it means to be a teacher. Some student teachers emphasized their role as emotional supporters of children, whereas others tended to speak more about the importance of efficiency and organization of the classroom. It is likely that these different orientations and associated styles of behavioral interaction are related in important ways to the types of relationships that teachers tend to form with students. Brophy (1985) suggested that teachers view themselves primarily as instructors or socializers and that these different perceptions impact the way in which they interact with students. Instructors tend to respond more negatively to students who are underachievers, unmotivated, or disruptive during learning tasks, whereas socializer teachers tended to act more negatively toward students they viewed as hostile, aggressive, or those who pushed away as teachers attempted to form relationships (Brophy, 1985). Although there is some preliminary evidence that teachers do vary in the pattern of relationships they form with children (Pianta, 1994), connections between these patterns and other teacher characteristics have yet to be elucidated.

How do teachers form this image of themselves as teachers? Several of the teachers in Calderhead and Robson’s (1991) study consistently referred to experiences with previous teachers as essential to their own ideas about teaching. The student teachers’ perceptions of past teachers ranged from very negative (intolerant, impatient, unsympathetic) to very positive (caring, attentive, friendly), and the students linked these perceptions to their thoughts about what it means to be a good or bad teacher. For example, one student teacher vividly recalled being ridiculed and embarrassed as a child by teachers who failed to take the time to explain things to her. She also remembered one teacher who took the time to help her understand. This student teacher described having patience with children as being extremely important to her own work as a teacher. Teachers’ images of their roles as teachers develop in part from their own experiences in school.

Additionally, teachers may rely on past experiences with other important people in their lives to help form their image of themselves as a teacher. Kesner (2000) gathered data on student teachers’ representations of attachment relationships with their own parents and showed that beginning teachers who viewed their relationships with their parents as secure were also those who formed relationships with students characterized as secure. In a related study, Horppu and Ikonen-Varila (2001) showed that beginning teachers’ representations of attachment with their parents related to their stated motives for their work and their beliefs about a kindergarten teacher’s work and goals in the classroom. Beginning teachers classified as having a secure-autonomous relationship with their parent(s) were more likely than those classified as insecure to express motives that were child-centered as well as centered on goals for the self. Teachers classified as secure also described more complex conceptions of a teacher’s work (involving social, emotional, and instructional components) and were more likely to view relationships with students as mutually satisfying (Horppu & Ikonen-Varila, 2001). Teachers’own personal histories of relationship experiences with parents and their representations of those experiences were associated with their current views about teaching, the degree to which they viewed teaching as involving a relational component, and their comfort with that relational component, demonstrating the extent to which multiple aspects of the teacher’s own representational system and belief system are interrelated and related to other components of the child-teacher dyadic system.

In a case-based extension of these ideas, Case (1997) suggested that one instance in which teachers’early relationships may be particularly important to their own classroom philosophy is in the case of othermothering in urban elementary schools. She described othermothering as “African American women’s maternal assistance offered to the children . . . within the African American community” (p. 25). Othermothering constitutes a culturally held belief in women’s responsibility for the raising of other mothers’ children, which for some women is enacted through the role of a teacher. Case (1997) described two African American teachers working in urban districts in Connecticut. Both of these women related the connections they made with children in the classroom to the experiences that they had with their own mothers as children. Describing her early experiences in rural North Carolina, one of the teachers stated,

At an early age, it was all self-esteem, believing in yourself. But one of the things that we valued most as a family was the way that we must treat other people. We must look to the values from within and realize that everybody’s human: They’re going to make mistakes, they’re going to fall flat on their faces sometimes, but you pick yourself up and say, “Well, I’ve learned from this.” (p. 33)

As this teacher describes her first day of teaching, the connection between these early experiences and her view of her role as a teacher becomes apparent:

When I first had this class, their faces were hanging down to the floor. . . . I had never seen such unhappy children. I felt as if they had no self-worth. I just couldn’t believe the first couple of days. They were at each other’s throats. I found that many of them thought that school was a place to come and act out, and now they are in cooperative groups, they share. It’s just that you start where they are. . . . I think it’s about empathy. You look at them and say, “It’s going to be a better day” and they say, “How did you know?” (pp. 34–35)

These findings (Case, 1997; Kesner, 2000; Horppu & Ikonen-Verida, 2001) suggest mechanisms by which teachers develop styles of relating to all of the children in their classrooms. Beyond a global relational style, teachers bring with them experiences, thoughts, and feelings that lead to specific styles of relating to certain types of children. Research in this area is scant, but there is a general recognition that the match or mismatch between teachers and students can be important to children’s development as well as to teachers’job satisfaction (Goodlad, 1991).

Teachers also hold beliefs about their efficacy in the classroom and associated expectations for children that are related to experiences with children and their own success and satisfaction. Teachers who believe that they have an influence on children can enhance student investment and achievement (Midgley, Feldlaufer, & Eccles, 1989). When teachers hold high generalized expectations for student achievement, students tend to achieve more, experience a greater sense of selfesteem and competence as learners, and resist involvement in problem behaviors during both childhood and adolescence (Eccles, 1983, 1993; Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 1998; Rutter, 1987; Weinstein, 1989). Furthermore, teachers who view self improvement and effort as more important than innate ability are more likely to have children who not only are more motivated but also report more positive and less negative affective states (Ames, 1992).

These studies, just a selective part of a much larger literature on teacher beliefs and student motivation (see Eccles & Roeser, 1998), call attention to the extent to which teacher beliefs, experiences, and expectations are involved within a model of child-teacher relationships. These beliefs, experiences, and expectations are closely intertwined with teachers’and students’behaviors toward one another. They change with developmental time and with experiences with specific children and stimulate loops of interaction in which changes in student motivation and achievement feedback on teacher beliefs in confirming or disconfirming ways.

In addition to psychological aspects of teachers as individuals as described earlier, other attributes of teachers warrant discussion in terms of their roles in a model of child-teacher relationships. These include teacher gender, experience and education, and ethnicity. Although the teacher workforce is overwhelmingly female, particularly at the younger grades (Goodlad, 1991), there is sufficient variability in teacher gender to examine its consequences for child-teacher relationships. By and large, this evidence is sparse, and the topic has not been a focus of dedicated study. However, anecdotal and survey data do suggest that teacher gender plays a role in the extent of children’s use of the teacher as a role model; not surprisingly, this is particularly true for male children and teachers (Goodlad, 1991; Holland, 1996). Male teachers, who are found more frequently in the older grades, are reported by children to provide role models and are described as important sources of support.

Holland (1996) suggested that, particularly for African American boys, an African American male teacher plays a key role in organizing male students’adoption of educational goals and behaviors.The extent to which thisfinding—as well as others involving the match between African American male students and teachers—is related to gender or race is at this time unknown and unexamined. In a related finding, teacher ethnicity appears to play a role in teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with students, particularly as their ethnicities interact with student ethnicities (Saft & Pianta, 2001). African American teachers (nearly all female) report more positive relationships (less conflict) with their students (of all ethnicities) than do Caucasian teachers, and they are particularly more positive (than White teachers) about their relationships withAfricanAmerican children.

Teacher experience, in and of itself, has shown little relation to teachers’own reports about the qualities of their relationships with children in the elementary grades (Beady & Hansell, 1981; Stuhlman & Pianta, in press). Battistich et al. (1997) reported that in a large sample of upper elementary school students there were no significant associations between child-reported or teacher-reported perceptions of the school as a caring community (which included an index of teacher emotional support) and teacher age, number of years teaching, education, or ethnic status. However, these data were aggregated within schools and related to each other at the school level, so they may mask significant associations for individual teachers and children.

In a study that elicited teachers’ representations of their relationships with specific students using an interview procedure (Stuhlman & Pianta, in press), the extent to which teachers’ reported negative emotional qualities in the relationship were related to their negative behaviors toward the children varied as a function of teacher experience.Teachers who were more experienced were more likely to have their represented negativity reflected in their behavior than were teachers with fewer than 7 years of experience. The extent to which the less experienced teachers held negative beliefs and experienced negative emotions in their relationship with a specific childwasnotrelatedtotheirnegativebehaviorwiththatchild. These data suggest some type of emotional buffering mechanism that may wane with more years in the profession.

Characteristics of Children

From the moment students enter a classroom, they begin to make impressions on a teacher, impressions that are important in the formation of the relationships that develop over the course of the school year. Though it is likely that a wide variety of child characteristics, behaviors, and perceptions are associated with the development of their relationships with teachers, our understanding of these associations is limited and derived in part due from inferences about how these characteristics function in relationships. Some characteristics, such as gender, are both static and readily apparent to teachers, whereas others are more psychological or behavioral in nature.

Young girls tend to form closer and less conflictual relationships with their teachers, as noted in studies using teacher (Hamre & Pianta, 2001) and child (Bracken & Crain, 1994; Ryan, Stiller, & Lynch, 1994) reports on the quality of the relationship as well as in studies in which trained observers rated relationship quality (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999). Even as late as middle school, girls report higher levels of felt security and emulation of teachers than do boys (Ryan et al., 1994).

These gender differences may be related in part to the fact that boys typically show more frequent antisocial behaviors, such as verbal and physical aggression. These behaviors are, in turn, associated with the formation of poorer child-teacher relationships, as rated by trained observers (Ladd et al., 1999). It is important to note, however, that the majority of teachers in primary grades are females and that there are no existing data to suggest how male teachers may relate differentially to boys and girls in the primary grades. There is some evidence that as children mature, gender matching may be important in the formation of closeness with teachers. In one study, 12th-grade girls reported that they perceived greater positive regard from female teachers whereas the boys in the study perceived more positive regard from male teachers (Drevets, Benton, & Bradley, 1996). However, this gender specificity in children’s perceptions was not reported by the 10th- and 11th-grade students in this study.

Another child characteristic that is apparent to teachers is ethnicity. As with the findings on gender, there are preliminary indications that the ethnic match between teacher and child is associated with more positive relationships (Saft & Pianta, 2001). Caucasian children tend to have closer relationships with teachers, as indicated in studies using reports by teachers (Ladd et al., 1999) and students (Hall & Bracken, 1996). Unfortunately, teachers in most of these studies are Caucasian, so it is difficult to make any clear inference about the impact of a child’s ethnicity on his or her ability to form a strong relationship with teachers and other school personnel.

Other child characteristics that may be linked to the relationship that children develop with teachers include their own social and academic competencies and problems (Ladd et al., 1999; Murray & Greenberg, 2000). In a large sample of elementary school children, Murray and Greenberg reported that children’s own reports of feeling a close emotional bond with their teacher were related to their own and their teachers’ reports of problem behavior and competence in the classroom. Similarly, Pianta (1992) reported that teachers’ descriptions of their relationships with students in kindergarten were related to their reports of the child’s classroom adjustment and, in turn, related to first-grade teacher reports. A cycle of child behavior and interactions with the teacher appeared to influence (in part) the teachers’relationship with the child, which in turn was independently related (along with reports of classroom behavior) to teacher reports of classroom adjustment in the next grade. Ladd et al. (1999) suggested that relational style of the child is a prominent feature of classroom behavior.

Also important to the formation of the child-teacher relationship, though less visible to teachers, are the thoughts and feelings of their students, including their general feelings about the school environment and about using adults as a source of support. Third through fifth graders from urban, at-risk schools who reported the highest levels of dissatisfaction with the school environment reported less social support at school and a more negative classroom social environment than did their more satisfied peers (Baker, 1999). Similarly, elementary school children who report an emotionally close and warm relationship with their teacher view the school environment and climate more positively (Murray & Greenberg, 2000). Clearly, one issue in sorting out associations (or lack thereof) of children’s judgments of school climate and the quality of child-teacher relationships is the experiential source of these judgments. Given the much greater weight on classroom experience in young children’s judgment of school climate, it is likely that these findings demonstrate the influence of childteacher relationships on children’s judgments of climate and social support in the broader school environment. Whether and how this relation changes with development, such that school climate plays a relatively greater role in judgments of the relational quality of classroom experiences over time, is at this time unknown.

Just as teachers make judgments about when to invest or not invest in a relationship, children, especially as they grow older, calculate their relational investment based on the expected returns (Muller, Katz, & Dance, 1999). Urban youths (largely African American males) enrolled in two supplemental programs near Boston reported investing more with teachers who show that they care yet are also able to provide structure and have high expectations for students progress.

Clearly, these child characteristics, behaviors, and perceptions are not independent of one another. As suggested earlier, boys tend to act out more in primary grades, and this behavior, rather than simply gender itself, may account for the conflict they have with teachers. Similarly, there is evidence linking child factors such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and disability classification, and the associations between these factors and the quality of the child-teacher relationship are likely to be complex. Nevertheless, what the child brings into the classroom each day is an important piece of the child-teacher relationship.

Representational Models

An individual’s representational model of relationships (Bowlby, 1969; Zeanah et al., 1993) is the set of feelings and beliefs that has been stored about a relationship that guides feelings, perceptions, and behavior in that relationship. These models are open systems: The information stored in them, while fairly stable, is open to change based on new experience. Also, representational models reflect two sides of a relationship (Sroufe & Fleeson, 1988). A teacher’s representational model of how children relate to teachers is both the teacher’s experience of being taught (and parented) and his or her own experience as a teacher.

Representational models can have an effect on the formation and quality of a relationship through brief, often subtle qualities of moment-to-moment interaction with children such as the adult’s tone of voice, eye contact, or emotional cues (Katz, Cohn, & Moore, 1996), and in terms of the tolerances that individuals have for certain kinds of interactive behaviors. Therefore, adults with a history of avoidant attachment, who tend to dismiss or diminish the negative emotional aspects of interactions, will behave differently in a situation that calls for a response to an emotionally needy child than will adults whose history of secure attachment provides support for perceiving such needs as legitimate and responding to them sensitively.

In Pedersen et al.’s (1978) case study, adults were asked to recall experiences with a particular teacher who had a reputation as exceptional. This was an attempt to examine (retrospectively) the features of experience associated with an influential teacher. These recollections describe the impact of a teacher who formed relationships with students that, according to their reports, made them feel worthwhile, supported their independence, motivated them to achieve, and provided them with support to interpret and cope with environmental demands. Students’ representations of their relationships with a specific teacher appeared to be a key feature of their experience in relationship with that teacher.

Teachers’ representations have been examined only recently. Based on interview techniques developed for assessment of child-parent relationships, Stuhlman and Pianta (in press) gathered information from 50 teachers of kindergarten and first-grade children. Teachers of first graders had relatively higher levels of negative emotion represented in relationships with students than did the kindergarten teachers. For both groups of teachers, representations of negative emotion were related to their discipline and negative affect in interactions with the children about whom they were interviewed. Teachers’ representations were only somewhat related to the child’s competence in the classroom, and teachers’ representations were related to their behavior with the child independent of the child’s competence. The Stuhlman and Pianta (in press) study suggests that teacher representations, while related in predicted directions to their ratings of child competence and to their behavior with the child, are not redundant with them, with indications that representations are unique features of the child-teacher relationship.

Muller et al. (1999) argued that teachers’ expectations for students are essential components of the development of positive or negative relationships with children. They suggested that teachers calculate expected payoffs from investing in their relationships with students. The authors provided an example of one teacher’s differential expectations for two students with very similar backgrounds. Both were Latino students with excellent elementary school records who were getting poor grades in middle school. Although both boys were involved with a peer group that encouraged cutting class, one student broke away from his friends to attend the teacher’s class. Interviews with the teacher suggested that she invested much more time and energy into this student, who she thought was less susceptible to peer pressure, because she believed she could have a greater influence on him than on the other.

Further work on representational aspects of child-teacher relationships is needed to distinguish these processes from general expectations and beliefs held by the child or teacher. At present, there is sufficient evidence from research on childparent relationships to posit that representational models, although assessed via individuals’ reports and behaviors, may in fact reflect properties of the relationship (Main, 1996) and therefore be better understood not as features of individuals but as relational entities at a different level of organization.

Information Exchange Processes: Feedback Loops Between Child and Teacher

Like any system, the components of the child-teacher relationship system interact in reciprocal exchanges, or loops in which feedback is provided across components, allowing calibration and integration of component function by way of the information provided in these feedback loops. In one way, dyadic relationships can be characterized by these feedback processes. For example, the ways that mother and child negotiate anxiety and physical proximity under conditions of separation characterize the attachment qualities of that mother-child relationship (Ainsworth et al., 1978). As in the attachment assessment paradigm, feedback processes are most easily observed in interactive behaviors but also include other means by which information is conveyed from one person to another. What people do with, say or gesture to, and perceive about one another can serve important roles in these feedback mechanisms.

Furthermore, the qualities of information exchange, or how it is exchanged (e.g., tone of voice, posture and proximity, timing of behavior, contingency or reciprocity of behavior), may be even more important than what is actually performed behaviorally, as it has been suggested that these qualities convey more information in the context of a relationship that does actual behavioral content (Cohn, Campbell, Matias, & Hopkins, 1990; Greenspan, 1989).

Teacher-Child Interactions

Although there is a large literature on interactions between teachers and children (e.g., Brophy & Good, 1986; Zeichner, 1995), it is focused almost entirely on instruction. Recent work has integrated a social component to understanding instructional interactions (e.g., Rogoff, 1990), but in the majority of studies of teachers’ behaviors toward children in classrooms, the social, emotional, and relational quality of these interactions is almost always neglected.

Teachers and children come together at the beginning of the year, each with their own personality and beliefs, and from the moment the children enter the classroom, they begin interacting with one another. It is through these daily interactions, from the teacher welcoming students in the morning to the moment the children run out the door to catch the bus, that relationships develop. Recently, investigators have gained a better understanding of the specific types of interactions that lead to the formation of relationships between students and teachers. As with studies on individual characteristics and perceptions, these relational interaction studies are imbedded within a much larger field of research on classroom interactions.

It is not surprising that teachers’interactions with children are related to characteristics of the children themselves. Peerrejected children tend to be more frequent targets of corrective teacher feedback than nonrejected classmates (e.g., Dodge, Coie, & Brakke, 1982; Rubin & Clarke, 1983), and it has been repeatedly demonstrated that teachers direct more of their attention to children with behavior or learning problems and to boys (e.g., Brophy & Good, 1974). Similarly, children rated as more competent in the classroom are more frequent recipients of sensitive child-teacher interactions and teachers’ positive affect (Pianta et al., 2002). Once again, when considering child-teacher interactions in the context of this dyadic relationship system, it is important to recognize that there are strong bidirectional relations between child characteristics and teacher behavior.

Research on teacher-child interactions as they relate to student motivation provides some insight into associations between interactions and relationships. Skinner and Belmont (1993) suggested that although motivation is internal to a child, it requires the social surrounding of the classroom to flourish. They suggested three major components to this social environment: involvement, autonomy support, and structure. Involvement is defined as “the quality of interpersonal relationships with teachers and peers. . . . [T]eachers are involved to the extent that they take time for, express affection toward, enjoy interaction with, are attuned to, and dedicate resources to their students” (p. 573). This definition closely resembles definitions of a positive child-teacher relationship.

Skinner and Belmont (1993) found that upper elementary teachers’ reports of greater involvement with students were the feature of the social environment most closely associated with children’s positive perceptions of the teacher. Furthermore, they found a reciprocal association between teacher and student behavior such that teacher involvement facilitated children’s classroom engagement and that this engagement, in turn, led teachers to become more involved. Students who are able to form strong relationships with teachers are at an advantage that may grow exponentially as the year progresses. Similar research conducted with adolescents suggests that student engagement with teachers is dependent not only on their feelings of personal competence and relevance of course material but also on students’ perceptions of feelings of safety and caring in the school environment (Roeser, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2000).

Teachers’ Interactions With Other Students as Observed by Peers

An interesting line of recent research has focused on teachers as social agents of information and the role that their interactions with a given student serve as sources of information about child-teacher relationships for the other students in the classroom (Hughes, Cavell, & Willson, in press; White & Kistner, 1992). Hughes et al. (in press) reported that classmates’ perceptions of the quality of the relationship between their teacher and a selected child in the classroom were related to their own perceptions of the quality of their relationship with the teacher. It is important to note that these relations were observed independent of the characteristics of the child, suggesting that this is a unique source of social information in the classroom setting that has consequences for the impressions that children form of their teacher (and vice versa), which in turn could relate to help seeking and other motivational and learning behaviors (Newman, 2000). In a related study, White and Kistner (1992) examined relations between teacher feedback and children’s peer pBibliography: in early elementary students, finding that teachers’negatively toned feedback toward selected children was related negatively to classmates’pBibliography: for these children.

With regard to understanding the role that interactive behaviors play in the context of the entire teacher-child relationship, patterns of behavior appear to be more important indicators of the quality of a relationship than do single instances of behavior. It is not the single one-time instance of child defiance (or compliance) or adult rejection (or affection) that defines a relationship. Rather, it is the pattern of child and adult responses to one another—and the quality of these responses. Pianta (1994) argued that these qualities can be captured in the combination of degree of interactive involvement between the adult and child and the emotional tone (positive or negative) of those interactions. Birch and Ladd (1996) pointed out that relationship patterns can be observed in global tendencies of the child in relation to the adult—a tendency to move toward, move away, or move against.

Also involved in the exchange of information between adult and child are processes related to communication, perception, and attention (Pianta, 1999). For example, how a child communicates about needs and desires (whiny and petulant or direct and calm), how the teacher selectively attends to different cues, or how these two individuals interpret one another’s behavior toward each other (e.g. “This child is needy and demanding” vs. “This child seems vulnerable and needs my support”) are all aspects of how information is shaped and exchanged between child and teacher. Perceptions and selective attending (often related to the individuals’ representations of the relationship; see Zeanah et al., 1993) act as filters for information about the other’s behavior. These filters can place constraints on the nature and form of information present in feedback loops and can be influential in guiding interactive behavior because they tend to be selffulfilling (Pianta, 1999). Over time, these feedback and information exchange processes form a structure for the interactions between the adult and child.

In sum, processes involving transmission of information via behavioral, verbal, and nonverbal channels play a central role in the functioning of the dyadic system of the childteacher relationship. For the most part, research has focused on descriptions of instructional behaviors of teachers, on teachers’ differential attentiveness to children, and on children’s engagement and attention in learning situations (see Brophy & Good, 1974). There is much less information available on social and affective dimensions of child-teacher interactions, nonverbal components of interaction, and the dynamics of multiple components of interaction in classroom time or developmental time. Furthermore, how these interactive processes are shaped by and shape school- and systemlevel parameters (e.g. school climate, policies on productive use of instructional time) is even less well described. Nonetheless the available data provide support for the developmental systems perspective of child-teacher relationships and the complex ways in which information is transmitted through multiple channels between child and teacher and the fact that this information plays an important role in children’s and teachers’perceptions and representations of one another.

External Influences

Systems external to the child-teacher relationship also exert influence. Cultures can prescribe timetables for expectations about students’ performance or the organization of schools (Sameroff, 1995) that can shape how students and teacher relate to one another. What other external influences shape student-teacher relationships? State regulations mandate standards for student performance that affect what teachers must teach, and at times how they must teach it. School systems have codes for discipline and behavior, sometimes mandating how discipline will be conducted. States and localities prescribe policies and regulations regarding student-teacher ratios, the placement of children in classrooms, at what grade students move to middle school, or the number of teachers a child comes into contact with in a given day. Teachers also have a family and personal lives of their own.

Structural Aspects of the School Environment

Structural variables in classrooms and schools play an important role in constraining child-teacher relationships through direct effects on the nature of interaction and indirectly via attributes of the people involved. For example, observations of child-teacher interactions in kindergarten and first grade are observed to vary as a function of the ratio of children to adults in the room, the activity setting (small or large group), and the characteristics of the children in the classroom. In large samples of students in kindergarten (Pianta et al., 2002) and first grade (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network [ECCRN], 2001), children in classrooms with a low ratio of children to adults receive more frequent contacts with their teacher and contacts that are more positive emotionally. Teachers in these classrooms are observed to be more sensitive. Similarly, in both of these samples, when the activity setting was large-group or whole-class instruction, children had many fewer contacts with the teacher than when in small groups. In a sample of more than 900 first-grade classrooms, children, on average, were engaged in individual contact with their teachers on approximately 4 occasions during a 2-hr morning observation (NICHD ECCRN, 2001).

It appears that attributes of the class as a whole are related to the quality of interactions that teachers have with an individual child (NICHD ECCRN, 2001). Therefore, when the classroom is composed of a higher percentage of African American children or children receiving free-reduced lunch, teachers were observed to show less emotional sensitivity and support and lower instructional quality in their intersections with an individual (unselected) student. These findings suggest perhaps that the racial and poverty composition of the classroom may represent demand features of the children, which can result in a teacher’s behaving more negatively with children (with attendant consequences for their relationships) when high as a function of the concentration of children with these characteristics in classroom. This suggestion is supported by survey data demonstrating that teachers with high concentrations of ethnic minority or poor children in their classrooms experience a greater degree of burden (RimmKaufman, Pianta, Cox, & Early 1999).

Finally, the level or organization of the school also affects how child and teacher relationships form and function. Eccles and Roeser (1998) summarized findings suggesting that as children move through elementary school and into middle school, there is an increasing mismatch between their continuing needs for emotional support and the school’s increasing departmentalization and impersonal climate.

School Climate and Culture