View sample guiding educational reform research paper. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a psychology research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

In this research paper, my focus is on how educational psychology’s knowledge base can best be applied to twentyfirst-century educational reform issues and—in so doing— discuss what policy implications arise. I address this topic in five parts:

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

- What we have learned.

- How work in educational psychology has contributed to effective reform.

- What research directions are still needed.

- How our knowledge base can best address issues of concern in the current reform agenda.

- What policy issues must be addressed in twenty-firstcentury educational reform efforts.

Prior to beginning these topics, however, I would like to clarify what I understand to be the purpose and function of educational psychology as a credible knowledge base and science.

The definitions of educational psychology have been varied over the past century of psychological research on learning, but one commonality exists: There is widespread agreement that educational psychology is by definition an applied science. What that means to me is that it functions to conduct applications-driven research, development, and evaluation in the areas of human motivation, learning, and development. This research creates knowledge that informs practice and can be applied to the teaching and learning process in school settings in ways that enhance human potential and performance.

Applications of educational psychology’s knowledge base must of necessity acknowledge the complexities of individuals and the educational systems and structures within which they operate throughout kindergarten to adult school settings. Systemic and multidisciplinary attention to how what we have learned about teaching and learning from diverse areas of research—including cognitive, motivational, social, and developmental—must be integrated with applications in schooling areas that include curriculum, instruction, assessment, teacher development, and school management (to name a few). Those of us working in this arena must therefore understand the context of schools as living systems—systems that operate at personal, technical, and organizational levels and that support personal, organizational, and community levels of learning; this places a responsibility on those working in the field of educational psychology to have both a breadth and depth of knowledge—not only about teaching and learning at the individual or process levels, but also about how this knowledge can be comprehensively integrated for application in diverse school settings and systems.

Given its applied nature and broad function, educational psychology also has to satisfy the tension between scientifically defensible research and research that has ecological validity in pre-K–20 school settings. This tension has been with the field since the beginning, and we have learned much in over a century of research. One of our biggest challenges will be to educate others about what we have learned and in the process help them recognize our current and future roles in twenty-first-century educational reform efforts.

What Have We Learned about Learning, Teaching, Cognition, Motivation, Development, and Individual Differences?

To establish a context for discussing what we have learned that is applicable to educational reform issues, this section begins with a brief review of major educational reform initiatives occurring nationally and internationally in the areas of assessment, standards, and accountability. It includes my perceptions of how educational psychology has been involved in reform movements and how the growing knowledge base can address reform issues in the twenty-first century. An example of a comprehensive project to define and disseminate the psychological knowledge base on learning, motivation, and development is then provided. This example involves the work of the APA Task Force on Psychology in Education (1993) and the APAWork Group of the Board of Educational Affairs (1997)—notably, their development and dissemination of the Learner-Centered Psychological Principles as a set of guidelines and a framework for school redesign and reform.

Defining Educational Reform and the Status of Twenty-First-Century Reform Efforts

Education reform has been a topic in the forefront for educators, researchers, policy makers, and the public since the 1983 Nation at Risk report. From the 1990s into this century, reform efforts have focused on a number of issues, including state and national academic standards, standardized state and national testing, and increased accountability for schools and teachers. The overall goal of all these efforts has been to create better schools in which more students learn to higher levels (Fuhrman & Odden, 2001). In the process of moving toward this goal, there has been increased recognition that improvements are needed in instruction and professional development and that transformed practices rather than more of the old methods are needed. Acurrent focus on high-stakes testing has produced results in some schools but not in all. There is growing recognition that many practices need to be dramatically changed to reflect current knowledge about learning, motivation, and development. Educators and researchers are beginning to argue that a research-validated framework is needed to guide systemic reform efforts and that credible findings from educational psychology provide a foundation for this emerging framework.

Links between school reform and research in educational psychology are discussed by Marx (2000) in an introduction to a special issue of the Educational Psychologist on this topic. He points out that over the past quarter century, considerable progress has been made in providing new conceptions, principles, and models that can guide thinking about reforms that match what we know about learning, motivation, and development. Applying what we know to existing schools is not a simple matter, however, and requires the field to navigate through political and social issues and to attend to the best of what we know concerning the reciprocity of learning and change from a psychological perspective.

For example, Goertz (2001) argues that for effective reform we will need ways to balance compliance and flexibility in implementing standards-based reform that is sensitive to federal, state, and local contexts and needs. Educators will also need ways to ensure that substantial learning opportunities are provided for all learners in the system—including teachers, school leaders, students, and parents (Cohen & Ball, 2001). New policies will be needed as well as increased resources for capacity building if performance-based accountability practices are to be successful (Elmore & Fuhrman, 2001); ways to bridge the divide between secondary and postsecondary education will also be needed (Kirst & Venezia, 2001). Wassermann (2001) contends that the debate about the use of standardized tests to drive teaching must be balanced with collaborative efforts to define what is important to us in the education of our youth. Others are arguing for the increased use of assessment data to guide reform efforts, the need to attend to cultural changes, and the importance of strengthening the role of effective leadership and support for reform efforts (Corcoran, Fuhrman, & Belcher, 2001). To support these changes, Odden (2001) argues that new school finance models are needed to incorporate cost findings into school finance structures such that adequate fiscal resources are available to districts and schools for effective programs. Finally, these challenges must be met in an era of increased localization of funding.

The Role of Educational Psychology in Reform Efforts

The past century of research on learning has journeyed through a variety of theories that have alternately focused on behavioral, emotional, and cognitive aspects of learning. This range of theoretical perspectives, and the ways in which knowledge that is derived from these theories has been applied to school and classroom practices, have had (at best) a checkered history of successes and failures. For many educators, research-based has become a dirty word—a word that connotes something that is here today and gone tomorrow when the next research fad appears. Since the past decade or two of research, the picture appears to be changing. Current research in educational psychology is looking at learning from a more integrative perspective.

This integrative focus is based on a growing recognition from various perspectives (e.g., neurological brain research, psychological and sociological research) that meaningful, sustained learning is a whole-person phenomenon. Brain research shows that even young children have the capacity for complex thinking (e.g., Diamond & Hopson, 1998; Jensen, 1998; Sylwester, 1995). Brain research also shows that affect and cognition work synergistically, with emotion driving attention, learning, memory, and other important mental activities. Research evidence exists on the inseparability of intellect and emotion in learning (e.g., Elias, Zims, et al., 1997; Lazarus, 2000) and the importance of emotional intelligence to human functioning and health (e.g., Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). For example, brain research related to emotional intelligence, reported by Goleman (1995), confirms that humans have an emotional as well as an intellectual (or analytical) brain, both of which are in constant communication and involved in learning.

Recent research is also revealing the social nature of learning. In keeping with this understanding, Elias, Bruene-Bulter, Blum, and Schuyler (1997) discuss a number of research studies, including those in neuropsychology, demonstrating that many elements of learning are relational—that is, based on relationships. Social and emotional skills are essential for the successful development of cognitive thinking and learning skills. In addition to understanding the emotional and social aspects of learning, research is also confirming that learning is a natural process inherent to living organisms (APA Work Group of the Board of Educational Affairs, 1997).

From my research and that of others who have explored differences in what learning looks like in and outside of school settings, several things become obvious (e.g., McCombs, 2001b; Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001). Real-life learning is often playful, recursive, and nonlinear—engaging, self-directed, and meaningful from the learner’s perspective. But why are the natural processes of motivation and learning seen in real life rarely seen in most school settings? Research shows that self-motivated learning is only possible in contexts that provide for choice and control. When students have choice and are allowed to control major aspects of their learning (such as what topics to pursue, how and when to study, and the outcomes they want to achieve), they are more likely to achieve self-regulation of thinking and learning processes.

Educational models are thus needed to reconnect learners with others and with learning—person-centered models that also offer challenging learning experiences. School learning experiences should prepare learners to be knowledge producers, knowledge users, and socially responsible citizens. Of course, we want students to learn socially valued academic knowledge and skills, but is that sufficient? In the twenty-first-century world, content is so abundant as to make it a poor foundation on which to base an educational system; rather, context and meaning are the scare commodities today. This situation alters the purpose of education to that of helping learners communicate with others, find relevant and accurate information for the task at hand, and be colearners with teachers and peers in diverse settings that go beyond school walls.

To move toward this vision will require new concepts defining the learning process and evolving purpose of education. It will also require rethinking current directions and practices. While maintaining high standards in the learning of desired content and skills, the learner, learning process, and learning environment must not be neglected if we are to adequately prepare students for productive and healthy futures. State and national standards, however, must be critically reevaluated in terms of what is necessary to prepare students to be knowledgeable, responsible, and caring citizens. Standards must move beyond knowledge conservation to knowledge creation and production (Hannafin, 1999). The current focus on content must be balanced with a focus on individual learners and their holistic learning needs in an increasingly complex and fast-changing world.

The needs of learners are also changing and an issue of concern given its relationships to problems such as school dropout is that of youth alienation. Ryan and Deci (2000) maintain that alienation in any age population is caused by failing to provide supports for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Meeting these needs are also essential to healthy development and creating contexts that engender individual commitment, effort, and high-quality performance. Unfortunately, there are too many examples in the current educational reform agenda of coercive and punitive consequences for students, teachers, and administrators when students fail to achieve educational standards on state and national tests.

Educational psychology’s growing knowledge base supports comprehensive and holistic educational models. A current challenge is to find these models and link their successful practices to what has been demonstrated relative to the needs of learners in research on learning, motivation, and development. The stories of teachers and other educators must also become part of our credible evidence. For example, Kohl, founder of the open school movement, shares his 36-year experience as a teacher working in dysfunctional, poverty-ridden urban school districts (in Scherer, 1998). He emphasizes the importance of teachers projecting hope— convincing students of their worth and ability to achieve in a difficult world. Kohl advocates what he calls personalized learning based on caring relationship and respect for the unique way each student perceives the world and learns. Respecting students, honoring their perspectives, and providing quality learning are all ways that have been validated in research from educational psychology and related fields. Research from a multitude of studies and contexts has demonstrated the efficacy of these strategies for engaging students in learning communities that encourage invention, creativity, and imagination.

The Learner-Centered Psychological Principles

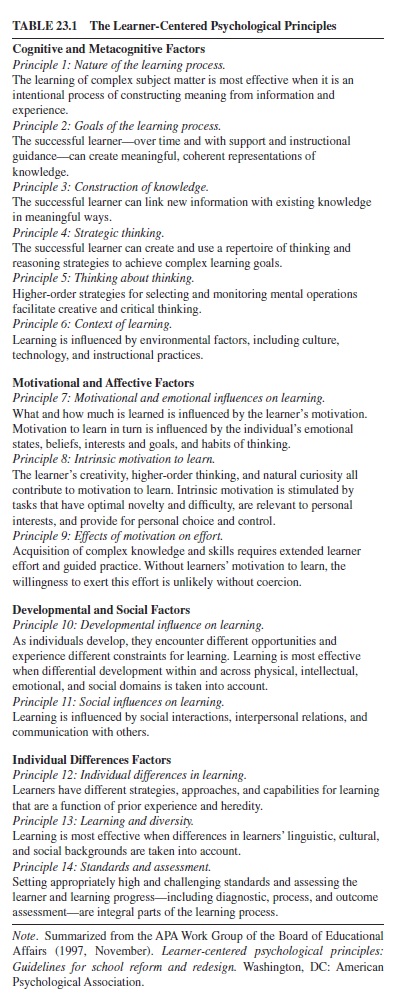

In keeping with an awareness of these trends, proactive efforts have been made in the past decade to make educational psychology’s knowledge base more visible and accessible to educators and policy makers. One such example is the work of the American Psychological Association (APA). Beginning in 1990, the APA appointed a special Task Force on Psychology in Education, one of whose purposes was to integrate research and theory from psychology and education in order to surface general principles that have stood the test of time and can provide a framework for school redesign and reform. The result was a document that originally specified twelve fundamental principles about learners and learning that taken together provide an integrated perspective on factors influencing learning for all learners (APA Task Force on Psychology in Education, 1993). This document was revised in 1997 (APA Work Group of the Board of Educational Affairs, 1997) and now includes 14 principles that are essentially the same as the original 12 principles, except that attention is now given to principles dealing with learning and diversity and with standards and assessment.

The 14 learner-centered principles are categorized into four research-validated domains shown in Table 23.1. Domains important to learning are metacognitive and cognitive, affective and motivational, developmental and social, and individual differences. These domains and the principles within them provide a framework for designing learner-centered practices at all levels of schooling. They also define learnercentered from a research-validated perspective.

Defining Learner-Centered

From an integrated and holistic look at the principles, the following definition of learner-centered emerges: The perspective that couples a focus on individual learners (their heredity, experiences, perspectives, backgrounds, talents, interests, capacities, and needs) with a focus on learning (the best available knowledge about learning and how it occurs and about teaching practices that are most effective in promoting the highest levels of motivation, learning, and achievement for all learners). This dual focus then informs and drives educational decision making. The learner-centered perspective is a reflection in practice of the learner-centered psychological principles in the programs, practices, policies, and people that support learning for all (McCombs & Whisler, 1997, p. 9).

This definition highlights that the learner-centered psychological principles apply to all learners—in and outside of school, young and old. Learner-centered is also related to the beliefs, characteristics, dispositions, and practices of teachers. When teachers derive their practices from an understanding of the principles, they (a) include learners in decisions about how and what they learn and how that learning is assessed; (b) value each learner’s unique perspectives; (c) respect and accommodate individual differences in learners’ backgrounds, interests, abilities, and experiences; and (d) treat learners as cocreators and partners in teaching and learning.

My research with learner-centered practices and selfassessment tools based on the principles for teachers and students from K–12 and college classrooms confirms that what defines learner-centeredness is not solely a function of particular instructional practices or programs (McCombs & Lauer, 1997; McCombs & Whisler, 1997). Rather, it is a complex interaction of teacher qualities in combination with characteristics of instructional practices—as perceived by individual learners. Learner-centeredness varies as a function of learner perceptions that in turn are the result of each learner’s prior experiences, self-beliefs, and attitudes about schools and learning as well as their current interests, values, and goals. Thus, the quality of learner-centeredness does not reside in programs or practices by themselves.

When learner-centered is defined from a research perspective, it also clarifies what is needed to create positive learning contexts and communities at the classroom and school levels. In addition, it increases the likelihood of success for more students and their teachers and can lead to increased clarity about the requisite dispositions and characteristics of school personnel who are in service to learners and learning. From this perspective, the learner-centered principles become foundational for determining how to use and assess the efficacy of learner-centered programs in providing instruction, curricula, and personnel to enhance the teaching and learning process. The confirm that perceptions of the learner regarding how well programs and practices meet individual needs are part of the assessment of ongoing learning, growth, and development.

Contributions of Educational Psychology to Effective Reform

In looking across the recent works in the field of educational psychology, a number of trends emerge. Most significant from my perspective are the following:

- Acknowledging the complexity of human behavior and the need for integrative theories and research that contextualize teaching and learning in schools as living systems that are themselves complex, dynamic, and built on both individual and relational principles.

- Looking at humans and their behavior holistically and focusing not only on cognitive and intellectual processes, but also on social and emotional processes that differentially influence learning, motivation, and development.

- Situating the study of teaching and learning in diverse school contexts and in particular content domains with a mix of quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

- Seeing teachers as learners whose own professional development must mirror the best of what we know about learning, motivation, and development.

- Rethinking critical assumptions about human abilities and talents, reciprocity in teacher and learner roles, and the function and purpose of schooling so that we can better prepare students for productive contributions to a global world and lifelong learning with emerging technologies.

- Acknowledging the central role of learners’ thinking and perceptions of their experiences in learning and motivation—for all learners in the system, including teachers, administrators, parents, and students.

We are in an exciting era of transformation and change— an era where the knowledge base in educational psychology has the opportunity to play a significant role in shaping our K–20 educational systems for the better. Particularly relevant to educational reform is knowledge being gained in the following areas. My intention here, however, is to describe more broadly how other areas of research in the field of educational psychology are informing issues in educational reform and the design of more effective learning systems.

Dealing With Increased Student Diversity

An issue of growing concern is the record number of students entering public and private elementary and secondary schools (Meece & Kurtz-Costes, 2001). This population is more diverse than ever before, with almost 40% minority students in the total public school population. Wong and Rowley (2001) offer a commentary on the schooling of ethnic minority children, cautioning that researchers should be sensitive to the cultural biases of their research with populations of color, recognize the diversity within ethnic groups, limit comparisons between groups, integrate processes pertaining to ethnic minority cultures with those of normative development, examine cultural factors in multiple settings, balance the focus on risks and problems with attention to strengths and protective factors, and examine outcomes other than school achievement. There is a need for comprehensive and coherent frameworks that allow differentiation of common issues (e.g., all children being potentially resistant to school because of its compulsory nature) to identify additional factors (e.g., cultural dissonance between school norms and ethnic culture norms) related to resistance to school. Multiple contexts should be studied, longitudinal studies undertaken, and sophisticated statistical tools applied.

Okagaki (2001) argues for a triarchic model of minority children’s school achievement that takes into account the form and perceived function of school, the family’s cultural norms and beliefs about education and development, and the characteristics of the child. The significant role of perceptions, expectations for school achievement, educational goals, conceptions of intelligence, and self-reported behaviors and feelings of efficacy are discussed as they influence successful strategies for the education of minority children. Home, school, and personal characteristics must all be considered, with particular attention paid to practices that facilitate positive teacher-child and child-peer interactions. The culture of the classroom must be made more visible and understandable to children from different cultural backgrounds—carefully considering the depth and clarity of communications with parents, helping students and parents see the practical relevance of obtaining a good education, thinking through how what we do in schools might have stereotyping effects for students, and recognizing that families have different theories about education, intelligence, parenting, and child development.

It is generally recognized that unacceptable achievement gaps exist between minority and nonminority children and that dropout rates are higher for some ethnic groups. Longitudinal research by Goldschmidt and Wang (1999) using National Educational Longitudinal Study (NELS) database on student and school factors associated with dropping out in different grades shows that the mix of student risk factors changes between early and late dropouts, with family characteristics being most important for late dropouts. Being held back was the single strongest predictor of dropping out for both early and late dropouts, but misbehaving was the most important factor in late dropouts. Hispanics are more likely to drop out than are African Americans and African Americans are more likely to drop out than are Whites. These differences are partly accounted for by differences in family, language, and socioeconomic factors. Associations between racial groups and factors such as being below expected grade levels, working while in school, and having poor grades also contribute to the differences in cultural groups.

Interventions that show promise for reversing these negative trends include social support and a focus on positive school climates. Lee and Smith (1999) report research on young adolescents in the Chicago public schools that indicates there needs to be a balance of challenging and rigorous academic instruction with social support in the form of smaller, more intimate learning communities. Such a balance tends to eliminate achievement differences among students from different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds— particularly in math and reading. The biggest disadvantages in achievement are for students who attend schools with both little social support and low academic challenge and rigor; thus, social support is particularly effective when students also are in schools that push them toward academic pursuits. The balance needs to be one with a focus on learning and on learner needs.

Studying Development of Academic Motivation

Ryan and Patrick (2001) studied the motivation and engagement of middle school adolescents as a function of their perceptions of the classroom social environment. Changes in motivation and engagement were found to be a function of four distinct dimensions of the environment: (a) promoting interaction (discuss with, share ideas, get to know other students), (b) promoting mutual respect (respect each other’s ideas, don’t make fun of or say negative things to others), (c) promoting performance goals (compare students to others, make best and worst test scores and grades public, make it obvious who is not doing well), and (d) teacher support (respect student opinions, understands students’ feelings, help students when upset or need support in schoolwork). In general, if students perceived teacher support and perceived that the teacher promoted interaction and mutual respect, motivation and engagement were enhanced. On the other hand, if students perceived that their teacher promoted performance goals, negative effects on motivation and engagement occurred. Students with supportive teachers reported higher self-efficacy and increases in self-regulated learning, whereas with performance-goal-oriented teachers, students reported engaging in more disruptive behaviors. Ryan and Patrick conclude that becoming more student-centered means (a) attending to social conditions in the classroom environment as perceived by students and (b) providing practices that enhance students’ perceptions of support, respect, and interaction.

Our work with kindergarten-through college-age students over the past 8 years has revealed that learner-centered practices consistent with educational psychology’s knowledge base and the learner-centered psychological principles enhance learner motivation and achievement (McCombs, 2000a, 2001a; McCombs & Whisler, 1997; Weinberger & McCombs, 2001). Of particular significance in this work is that student perceptions of their teachers’ instructional practices accounts for between 45–60%, whereas teacher beliefs and perceptions only account for between 4–15% of the variance in student motivation and achievement. The single most important domain of practice for students in all age ranges are practices that promote a positive climate for learning and interpersonal relationships between and among students and teachers. Also important are practices that provide academic challenge and give students choice and control, that encourage the development of critical thinking and learning skills, and that adapt to a variety of individual developmental differences.

Using teacher and student surveys based on the learnercentered psychological principles, called the Assessment of Learner-Centered Practices (ALCP), teachers can be assisted in reflecting on individual and class discrepancies in perceptions of classroom practice and in changing practices to meet student needs (McCombs, 2001). Results of our research with the ALCP teacher and student surveys at both the secondary and postsecondary levels have confirmed that at all levels of our educational system, teachers and instructors can be helped to improve instructional practices and change toward more learner-centered practices by attending to what students are perceiving and by spending more time creating positive climates and relationships—critical connections so important to personal and system learning and change.

For students who are seen as academically unmotivated, Hidi and Harackiewicz (2000) provide insights from a review of research related to academic motivation. The literature on interests and goals is reviewed and integrated, and the authors urge educators to provide a balance of practices that are sensitive to students’ individual interests, intrinsic motivation, and mastery goals—with practices that trigger situational interest, extrinsic motivation, and performance goals. This balance helps to shift the orientation to an internalization of interests and motivation and to promote positive motivational development for traditionally unmotivated students. The importance of the roles of significant others (e.g., teachers, parents, coaches) is also highlighted in terms of eliciting and shaping interests and goals in their students and children. Such an intrinsic-extrinsic motivational balance is deemed essential if educators are to meet diverse student needs, backgrounds, and experiences—that is, to adapt to the full range of student differences, we need the full range of instructional approaches, and these approaches need to be flexibly implemented.

The effects of student perceptions of their classroom environment on their achievement goals and outcomes was studied by Church, Elliot, and Gable (2001). The relationship between student perceptions and achievement outcomes was indirect; their influence first affected achievement goals, which in turn influenced achievement outcomes. If undergraduate students perceived that their instructor made the lecture interesting and engaging (compared to a situation in which they perceived that the instructor emphasized the importance of grades and performance evaluations or had grading structures that minimized the chance of being successful), they adopted mastery goal orientations (intrinsic motivation) versus performance goal orientations (extrinsic motivation). The authors conclude that stringent evaluation standards can lead to the adoption of performanceavoidance goals and hinder mastery goal adoption. For this reason, a study of both approach and avoidance orientations is needed because it moves research toward a broader framework that involves more complex integration of multiple constructs.

On the other hand, Midgley, Kaplan, and Middleton (2001) argue that the call to reconceptualize goal theory to acknowledge the positive effects of performance-approach goals is not warranted. They review studies that indicate the negative effects of performance-approach goals in terms of students’ use of avoidance strategies, cheating, and reluctance to cooperate with peers. They stress that it is important to consider for whom and under what conditions performance goals are good. Emphasizing mastery goals needs to be an integral part of all practices—particularly in this era, in which standards, testing, and accountability dominate educational practices and deep meaningful learning is in short supply.

In a longitudinal study of changes in academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence, Gottfried, Fleming, and Gottfried (2001) found that not only is intrinsic motivation a stable construct over time, but academic intrinsic motivation declines—particularly in math and science—over the developmental span. For this reason, Gottfried et al. argue that early interventions are needed to identify those students who may be at risk for low motivation and performance. Practices such as introducing new materials that are of optimal or moderate difficulty; related to student interests; meaningful to students; provide choice and autonomy; and utilize incongruity, novelty, surprise, and complexity are recommended.

Developing Students’ Metacognitive and Self-Regulation Competencies

Lin (2001) describes the power of metacognitive activities that foster both cognitive and social development. To accomplish this goal, however, knowledge about self-as-learner must be part of the metacognitive approach. Knowing how to assess what they know and do not know about a particular knowledge domain is not sufficient, and Lin’s research shows that knowledge about self-as-learner as well as supportive social environments help promote a shared understanding among community members about why metacognitive knowledge and strategies are useful in learning. The knowledge of self-as-learner can also be expanded to helping students know who they are and what their role is in specific learning cultures and knowledge domains or tasks; thus, this research highlights the application of the knowledge base on metacognition in ways that are holistic and assist in the development of both cognitive and social skills.

Another example of applying research that integrates cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and social strategies in the form of self-regulated learning (SRL) interventions is provided by Paris and Paris (2001). After reviewing what we have learned in this area, Paris and Paris define a number of principles of SRL that can be applied in the classroom, including the following:

- Helping students use self-appraisal to analyze personal styles and strategies of learning as a way to promote monitoring of progress, revising of strategies, and enhanced feelings of self-efficacy.

- Teaching self-management of thinking, effort, and affect such as goal setting, time management, reflection, and comprehension monitoring that can provide students with tools to be adaptive, persistent, strategic, and self-controlled in learning and problem-solving situations.

- Using a variety of explicit instructional approaches and indirect modeling and reflection approaches to help students acquire metacognitive skills and seek evidence of personal growth through self-assessments, charting, discussing evidence, and practicing with experts.

- Integrating the use of narrative autobiographical stories as part of students’ participation in a reflective community and as a way to help them examine their own selfregulation habits.

Additional principles are suggested by Ley and Young (2001, pp. 94–95) for embedding support in instruction to facilitate SRL in less expert learners. These principles are

- Guide learners to prepare and structure an effective learning environment; this includes helping learners to manage distractions by such strategies as charts for recording study time and defining what is an effective distractionfree study environment for them.

- Organize instruction and activities to facilitate cognitive and metacognitive processes; this includes strategies such as outlining, concept mapping, and structured overviewing.

- Use instructional goals and feedback to present student monitoring opportunities; this includes self-monitoring instruction and record keeping.

- Provide learners with continuous evaluation information and occasions to self-evaluate this includes helping students evaluate the success of various strategies and revising approaches based on feedback (Ley & Young, 2001, pp. 94–95).

Redefining Intelligence and Giftedness

There is a growing movement in theory and practice to reconceptualize what is meant by intelligence and giftedness. For example, Howard Gardner, in an interview by Kogan (2000), strongly argues that schools should be places where students learn to think and study deeply those things that matter and have meaning; schools should also help students learn to make sense of the world. He advocates a three-prong curriculum aimed at teaching— through a multiple intelligences approach—truth, beauty, and goodness. To teach truth, Gardner believes children need to understand the notion of evolution—including species variation and natural selection—and an appreciation of the struggle among people for survival. To teach beauty, Gardner would choose Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro as a pinnacle of beauty that portrays characters with deeply held emotions, offers the opportunity to help students appreciate other works of art, and inspires new creations. To teach goodness, Gardner chooses helping students understand a sequence of events such as the Holocaust, which shows what humans are capable of doing in both good and bad ways and provides a way for students to learn how others deal with pressures and dilemmas. Methods such as dramatic, vivid narratives and metaphors are recommended for involving students in their learning.

Other new developments influencing our understanding of intelligence are interdisciplinary fields of research that can offer multiple perspectives on complex human phenomena. Ochsner and Lieberman (2001) describe the emergence of social cognitive neuroscience that allows three levels of analysis: a social level concerned with motivational and social factors influencing behavior and experience; a cognitive level concerned with information-processing mechanisms that underlie social-level phenomena; and a neural level concerned with brain mechanisms that instantiate cognitive processes. Although still in its infancy, this multidisciplinary field promises to provide new insights about human functioning that can be useful in studying learners and learning in complex living systems such as schools. It also follows the trend toward more integrative and holistic research practices.

Consistent with this integrative trend is work by Robinson, Zigler, and Gallagher (2000) on the similarities and differences between people at the two tails of the normal curve—the mentally retarded and the gifted. As operationalized in tests of intelligence, deviance from the norm by performance two standard deviations from the mean (IQ of 70–75 or lower or IQ of 125–130 or higher) typically defines individuals who are mentally retarded or gifted, respectively. In looking at educational issues, Robinson et al. raise the following points:

- A one-size-fits-all paradigm for education does not accommodate individual differences in level and pace of learning—creating major problems for meeting the needs of diverse students in the current system designed for the average student.

- Strategies and approaches that work well with gifted children need to become models for improving the school experiences of all children.

- The basic philosophies and values of American schools are in keeping—at least theoretically—with the concept of adapting to individual differences in abilities, thereby providing an opportunity for our schools to become models of how best to deal with students in the two tails of the normal curve.

- More work is needed to solve the problems of economic and ethnic disadvantages that skew distributions of IQ scores and lead to discrimination by gender, race, and ethnic origin in terms of overplacement of minority students in special services and underrepresentation of minority students in gifted services.

- Research agendas in areas such as neurodevelopmental science, brain function, and genetics need to look at both ends in longitudinal studies that can provide insight into how to design interventions that overcome current maladaptive approaches to learning and performance that can hinder retarded and gifted students.

Understanding Components of Effective Teachers, Teaching, and Teacher Development

The past decade of research has seen an increased focus on teaching, teachers, and teacher education. Part of this increased attention is due to a growing understanding of the nature of learning and the role of teachers as lifelong and expert learners. Hoy (2000) argues for the need to place learning at the center of teaching, which means that teachers must have both deep content knowledge and a deep understanding of learning, motivation, and development. She also describes shifts in teacher education toward more integrative study that contextualizes content and pedagogical knowledge in social environments and inquiry-based curricula. Collaboration between and among students and teachers at all levels of schooling is another trend, along with encouraging reflection and field-based experiences. The concern is raised that educational psychology may get lost or marginalized in these trends, challenging us to think through how to situate and integrate our knowledge base and make processes of learning, motivation, and development more visible and accessible to teacher education students.

A specific look at the impact of teacher education on teachers of secondary mathematics is described by Borko et al. (2000). They argue that for teacher education to make a difference, both university experiences and field placements need to share comparable visions of reformed practice and teacher learning as situated in reformed practice. Such practice has methods situated (i.e., taught in the context of) in the content area (e.g., mathematics) and uses learning tasks that encourage multiple representations, solution strategies, and actively involve students in the learning process (e.g., having them make conjectures, provide justifications and explanations, and draw conclusions). Similarly, Zech, Cause-Vega, Bray, Secules, and Goldman (2000) describe a professional development model, content-based collaborative inquiry (CBCI), that engages educators in inquiring and constructing their own knowledge with a focus on their own and their students’ understanding and learning processes. Sustaining communities of inquiry to support lifelong teacher learning and educational reform is discussed as a way to shift practicing teachers’ orientations toward knowledge and knowing. By helping teachers focus on students’understanding in content domains, teachers’ critical reflection and assessment of their content knowledge and practice occurs. Collaborative inquiry helps uncover assumptions and build communities of practice based on trusting relationships.

Van den Berg and Ros (1999) remind us that teachers have individual questions, needs, and opinions about innovations and reform initiatives that must be attended to in any reform process. Using a concerns-based approach, different types of concerns were revealed at different stages of the innovation process and pointed to the need to attune innovation policies to these factors. Three clusters of concerns were identified: self-worries (e.g., amount of work involved in the innovation), task worries (e.g., classes too big to accommodate the innovation), and other worries (e.g., getting older colleagues to implement the innovation). The teachers’ concerns varied as a function of stage of the innovation (adoption, implementation, institutionalization), with self-worries more apparent in the adoption stage, task worries emphasized more in the implementation stage, and more other worries present in the institutionalization stage. The authors conclude with a plea to include opinions of teachers as well as orientation toward uncertainty in reform efforts and to provide explicit opportunities for reflection and dialogue in ongoing workshops and seminars.

The importance of collective teacher efficacy for student achievement is explored by Goddard, Hoy, and Hoy (2000). Collective teacher efficacy is defined as the perceptions of teachers in a school that the efforts of the faculty as a whole will positively affect students. A measure was developed and validated, and it was shown to have a positive relationship with student achievement in both reading and mathematics. It was also shown to differentiate achievement differences between schools; higher levels of collective teacher efficacy were related to gains in reading and mathematics achievement. When teachers share a sense of efficacy, they act more purposefully to enhance student learning and are supported organizationally to reflect on efforts that are likely to meet the unique needs of students.

Another critical variable is the degree to which teachers believe that instructional choice promotes learning and motivation. In spite of a large literature documenting the positive effects of choice—particularly on affective areas such as interest, ownership, creativity, and personal autonomy—many teachers continue to limit student choice. Flowerday and Schraw (2000) interviewed 36 practicing teachers to examine what, when, where, and to whom teachers offer choice. Among the findings were that teachers with high self-efficacy are more likely to provide instructional choices, as are teachers who themselves feel intellectually and psychologically autonomous and who are more experienced in particular subject areas. Most or all teachers agreed that choice should be used (a) in all grades, with older students needing more choices; (b) in a variety of settings, on different tasks, and for academic and social activities; and (c) in ways that offer simple choices first, help students practice making good choices, use team choices for younger students, provide information that clarifies the choice, and offer choices within a task.

New learner-centered professional development models for teachers focus on examining beliefs, empowerment, teacher responsibility for their own growth, teachers as leaders, and development of higher-order thinking and personal reflection skills (e.g., Darling-Hammond, 1996; Fullan, 1995; McCombs & Whisler, 1997). A key to teachers’ abilities to accept and implement these learner-centered models is support in the form of self-assessment tools for becoming more aware of their beliefs, practices, and the impact of these practices on students. Information from teachers’ selfassessments can then be used by teachers to identify—in a nonthreatening and nonjudgmental context—the changes in practice that are needed to better serve the learning needs of all students. In this way, teachers can begin to take responsibility for developing their own professional development plans.

A number of researchers are creating instruments to help teachers at all levels of the educational system (K–16) look at their own and their students’ perceptions of their learning experiences. To date, however, these tools are available in innovative teacher preparation programs and are not used in higher education in general largely because of reluctance among many college administrators to change current evaluation procedures that are based on direct instruction rather than holistic and constructivist models of teacher classroom practices.

Changes in evaluation procedures are occurring in teacher education, and current approaches support teacher growth with learning opportunities that (a) encourage reflection, critical thinking, and dialogue and (b) allow teachers to examine educational theories and practices in light of their beliefs and experiences. For teachers to change their beliefs to be compatible with more learner-centered and constructivist practices, however, they need to be engaged in reflective processes that help them become clearer about the gap between what they are accomplishing and what needs to be accomplished. Reflection is defined by Loughran (1996) as a recapturing of experience in which the person thinks about an idea, mulls it over, and evaluates it. Thus, Loughran argues that reflection helps develop the habits, skills, and attitudes necessary for teachers’ self-directed growth.

The work of my colleagues and me in developing a set of self-assessment and reflection tools for K–16 teachers (ALCP), in the form of surveys for teachers, students, and administrators, combines aspects of these approaches (McCombs & Lauer, 1997; McCombs, Lauer, & Pierce, 1998; McCombs & Whisler, 1997). However, the focus, is on identifying teacher beliefs and discrepancies between teacher and student perspectives of practices that can enhance student motivation and achievement—as a tool to assist teachers in reflecting on and changing practices as well as identifying personalized staff development needs.

Our research (McCombs & Lauer, 1997; McCombs et al., 1998; McCombs & Whisler, 1997) looked at the impact of teacher beliefs on their perceptions of their classroom practices as well as how teacher perceptions of practice differ from student perceptions of these practices. In a large-scale study of teachers and students, we confirmed our hypothesis about the importance—for student motivation, learning, and achievement—of those beliefs and practices that are consistent with the research on learners and learning. We also found that teachers who are more learner-centered are both more successful in engaging all students in an effective learning process and are themselves more effective learners and happier with their jobs. Furthermore, teachers report that the process of self-assessment and reflection—particularly about discrepancies between their own and their individual students’ experiences of classroom practices—helps them identify areas in which they might change their practices to be more effective in reaching more students. This is an important finding that relates to the how of transformation—that is, by helping teachers and others engage in a process of selfassessment and reflection, particularly about the impact of their beliefs and practices on individual students and their learning and motivation, a respectful and nonjudgmental impetus to change is provided. Combining the opportunity for teacher self-assessment of and reflection on their beliefs and practices (and the impact of these practices on individual students) with skill training and conversations and dialogue about how to create learner-centered K–16 schools and classrooms can help make the transformation complete.

Our research also revealed that teachers were not absolutely learner-centered or completely non-learner-centered. Different learner-centered teachers had different but overlapping beliefs. At the same time, however, specific beliefs or teaching practices could be classified as learner-centered (likely to enhance motivation, learning, and success) or nonlearner-centered (likely to hinder motivation, learning, and success). Learner-centered teachers are defined as those whose beliefs and practices were classified more as learnercentered than as non learner-centered. For example, believing all students learn is quite different from believing that some students cannot learn, the former being learner-centered and the latter being non-learner-centered. Learner-centered teachers see each student as unique and capable of learning, have a perspective that focuses on the learner’s knowing that the teacher’s beliefs promote learning, understand basic principles defining learners and learning, and honor and accept the student’s point of view (McCombs, 2000a; McCombs & Lauer, 1997). As a result, the student’s natural inclinations—to learn, master the environment, and grow in positive ways—are enhanced.

Capitalizing on Advances in Teaching and Learning Technologies

In a review of emerging Web-based learning environments, McNabb and McCombs (2001) point out that recent efforts to infuse electronic networking into school buildings via the Internet promise to promote connections among teachers and students in classrooms and those in the community at large. At the same time, uses of electronic networks for educational purposes cause large disturbances to the closed-ended nature of twentieth-century classroom practices (Heflich, 2001; Jones, 2001; McNabb, 2001). What becomes apparent are misalignments among curricular goals and resources, instructional practices, assessments, and accountability policies governing learning activities. The current shortage of qualified teachers available to the nation’s children on an equitable basis provides an additional challenge and opportunity for systemically transforming the nature of schooling to better meet the needs of twenty-first-century learners.

Haywood (personal communication, University of Edinburgh and Open University, June 15, 2001) argues that to overcome built-in inertia in traditional systems and the people they serve (students, teachers, administrators) requires new forms of learning, assessment, and community. New forms of communication that emerge in electroniclearning cultures may lead to new and better forms of socialization. Some of the bigger challenges in distance learning have been in how to help people handle change and in supporting new educational processes while working within the dominant traditional systems. The implementation issues range from determining the number of computers needed to how computers are used and how much they are used.

Current research at the Open University and other European institutions supporting some form of Web-based learning is now focusing on identifying the range of individual and group learning outcomes that must be assessed in both formative and summative ways. Other issues include finding new ways of communicating (Barnes, University of Bristol, personal communication, June 19, 2001) and identifying new social learning outcomes that result. Current challenges include communicating across several mediums in electronic-learning environments, looking at change over time, and finding ways to reward risk-taking at the personal and institutional levels as traditional K–20 systems make steps to change current learning and assessment paradigms.

Taking up the challenge of building learner-centered and technology-based classrooms, Orrill (2001) describes how teachers can be supported toward this goal with professional development that includes reflection, proximal goals, collegial support groups, one-on-one feedback, and support materials for teachers. The framework was based on the assumption that change is individual but must be supported over time in the social context of schools. Data were collected on 10 middle school teachers using simulations in project-based learning over a 4-month period. Refinements to the professional development framework included helping teachers to develop reflective skills prior to using proximal goals to focus reflection activities. Outside resources, oneon-one feedback, and collegial group meetings are then used to enhance the interplay between reflection and proximal goals. Guidance is essential as part of the development of reflection such that teachers see the importance of focusing on learner-centered goals that can be enacted immediately in refining the simulation activities.

Significant in using emerging technologies are personalization strategies. Just as Lin (2001) found higher levels of social development and achievement when metacognitive activities included self-as-learner knowledge, Moreno and Mayer (2000) report that personalized multimedia messages can increase student engagement in active learning. In a series of five experiments with college students, personalized rather than neutral messages resulted in better retention and problem-solving transfer. The importance of self-reference to student engagement and motivation has a long-standing research base, but it appears to be especially important in technology-based learning, particularly because it also influences higher learning outcomes.

The issue of scaling up technology-embedded and projectbased innovations in systemic reform is addressed by Blumenfeld, Fishman, Krajcik, Marx, and Soloway (2000). Studying urban middle schools, a framework is used to gauge the fit of these innovations with existing school capabilities, policy and management structures, and the organizational culture. The authors argue that the research community needs to create an agenda that can document how innovations work in different contexts and how to select reforms that match outcomes that are valued in their community and that are compatible with state and national agendas. Collaboration with teachers and administrators not only can help them adapt the innovation to make it achievable, but such collaboration also can promote an understanding of what will be require for sustainable systemic innovations that challenge traditional methods.

Of significance in this work with technology-based teaching and learning systems is the growing agreement that what we know about learning, motivation, development, and effective schooling practices will transfer to the design of these new systems (McNabb & McCombs, 2001). What we have learned that is particularly applicable includes findings summarized earlier in this research paper: Comprehensive dimensions of successful schools and learning environments must be concerned with (a) promoting a sense of belonging and agency, (b) engaging families in children’s learning and education, (c) using a quality and integrated curriculum, (d) providing ongoing professional development in both content and child development areas (including pedagogy), (e) having high student expectations, and (f) providing opportunities for success for all students.

Building New Learning Communities and Cultures

In most institutions of elementary, secondary, and higher education and progressively within professional development programs, teachers, administrators, policy makers, and those in content-area disciplines are isolated from each other. It is difficult to find examples of cross-department collaborations in course design, multidisciplinary learning opportunities, or organizational structures and physical facilities that allow interactions and dialogue among a range of educational stakeholders. Schools are isolated from emerging content in professional disciplines. Change is often mandated from above or from outside the system. Critical connections are not being made, and it is not difficult to foresee that change is then difficult and often resisted because of personal fears or insecurities. Those fears and insecurities disappear when people participate together in creating how their work gets done.

In developing effective learning communities and cultures, it is important to see the role of educational psychology’s knowledge base and the principles derived from this knowledge base in a systemic context. It is important to understand that education is one of many complex living systems that functions to support particular human needs (cf. Wheatley, 1999). Even though such systems are by their nature unpredictable, they can be understood in terms of principles that define human needs, cognitive and motivational processes, interpersonal and social factors, and development and individual differences. A framework based on researchvalidated principles can then inform not only curriculum, instruction, assessment, and related professional development but also organizational changes needed to create learnercentered, knowledge-centered, assessment-centered, and community-centered practices that lead to more healthy communities and cultures for learning.

Effective schools function as a healthy living system— an interconnected human network that supports teachers, students, and their relationships within communities of expert practice. In placing emphasis on the learner-centered developments of both students and teachers (as expert learners) within the context of emerging technologies, educational psychology’s knowledge based can be applied to building a fully functioning living system. This system supports a community network of members who are connected and responsive to each other. Community members interact in ways that precipitate learning and social development on all levels of the system. With the recent infusion and development of new and innovative technologies, researchers and scientists have imagined and implemented a wide range of methods for making this goal attainable.

Studies about the impact of the Internet on society and communities show that people in general are using the Internet at home, at the library, and at work for a variety of purposes including informal learning (Bollier, 2000; EnglishLueck, 1998; Nie & Erbing, 2000; Shields & Behrman, 2000). Children are finding connections to basic and advanced knowledge available in and generated through the community; some of this knowledge can conflict with that in textbooks. Youth’s career exploration and teachers’ professional development is best served in the community arena. Geographic cultures are converging electronically with other cultures via networks that allow easy movement in and out of many cultures. McNabb (2001) points out that historically research shows that positive cultural experiences based on mediated interactions with others are a vital part of children’s personal and interpersonal development that fosters one’s overall ability to learn (Boyer, 1995; Dewey, 1990; Feuerstein & Feuerstein, 1991; Vygotsky, 1978).

Wilson (2001) explains that culture refers to the set of artifacts and meanings (norms, expectations, tools, stories, language and activities, etc.) attached to a fairly stable group of people associating with each other; thus, as humans, each of us is (in a sense) multicultural and multilingual as we adapt to different cultural norms required by different groups and allegiances, a phenomenon that can proliferate on the Internet. It is community that helps bring coherence to our multicultural experiences. Wilson identifies belonging, trust, expectation, and obligation as defining characteristics of community. A sense of belonging within the community pertains to common purposes and values; trust pertains to acting for the good of the whole. Community carries an expectation among its members that the group provides value—particularly with respect to each other’s learning goals and with that a sense of obligation to participate in activities and contribute to group goals.

In addition, evidence shows that electronically networked cultures and communities are causing shifts related to control of these new cultures for learning. In the twentieth-century industrial era, the focal point within school systems tended to pertain to goals generated externally (top-down) with mass production designs for curriculum, instruction, and assessment purposes (Reigeluth, 2001). In twenty-first-century culture, the focal point is shifting to customized learning experiences and personal learning plans with goals based on each learner’s personal needs and interests facilitated by learner-centered pedagogy, content area understanding along a continuum from novice to expert developed through access to knowledge-centered materials and human resources in the community, and learners’ needs and achievements identified by formative assessments aligned to personal learning plans using assessmentcentered feedback loops.

Finally, the foregoing research, needs, and challenges facing today’s learners in K–20 systems also face preservice and in-service teachers. Researchers are increasingly calling for learning and professional development approaches that lead to what they call emerging communities of practice. This idea is in keeping with the recognition that electronic-learning technologies allow for nonlinear emergent learning and new paradigms of assessment. Emerging technologies also allow for a variety of learning communities and cultures, including communities of interest, communities of sharing, and communities of caring—all of which can be part of the experience at various points in time and contribute to both higher engagement and higher learning outcomes.

What Research Directions Are Needed?

This section provides what I see as basic and applied research directions that can foster the usefulness of educational psychology’s contributions to education and educational reform during the twenty-first century. All of these directions are then considered in light of implementation and evaluation implications as they are applied in the context of school and teacher accountability issues.

Basic Research Directions

In making the knowledge base from educational psychology more visible and accessible to educators and policy makers, some basic research directions are needed. From my own perspective, a number of suggestions can be made, including the following:

- Research that can further refine and elucidate alternative conceptions of ability and intelligence and broaden our understanding of the interplay between cognitive, affective, neurobiological, and social factors that influence the development of competencies.

- Research on voluntary study groups, effective uses of problem-based learning, intersections of cooperative learning and curriculum, strategies for professional development and follow-up support for cooperative learning, and how well cooperative learning works for gifted students or other students at the margins.

- Research on adult literacy, along with more research on how teaching word recognition also affects normal and gifted readers (not just struggling readers) and how to develop teachers to deliver motivational reading and writing programs.

- Research on the cultural aspects of learning and contrasts between activity theory and contextualism as alternative views for understanding the sociocultural context of the teaching and learning process.

- Research that explores relations between self-regulation and volition, the development of self-regulation in children, self-regulation and the curriculum, and selfregulation across the life span.

Applied Research Directions

Along with these basic research directions, more research is needed on the contexts of learning environments and the complex interactions between personal, organizational, and community levels of learning in schools as living systems; this includes attention to applied research in the following areas:

- Research on teacher development, including what teachers cite as the biggest challenge—the students themselves. Excellent teaching is a complex balancing act, and there are no quick fixes to producing excellent teachers.

- Research on what can be learned about learning and human adaptability to change during the implementation phase as new and existing teachers and others in our existing places called school begin to increasingly use electronic-learning technologies in new ways. These new ways of learning promise to be the catalyst for systems change and to a new paradigm for learning and assessment within electronically networked schools.

- Research to better understand the comprehensive dimensions of successful schools as (a) promoting a sense of belonging and agency, (b) engaging families in children’s learning and education, (c) using a quality and integrated curriculum, (d) providing ongoing professional development in both content and child development areas (including pedagogy), (e) having high student expectations, and (f) providing opportunities for success for all students.

- Research to identify the best socialization experiences for positive adjustment with diverse student populations— examining how children’s understanding of rules and norms change, how these rules are complementary or compatible with peer and adult norms, what differential impacts reward structures that teachers establish have depending of students’ age and family environment, and further work on student beliefs and perceptions of social support from teachers and peers.

- Research that identifies teacher preparation practices that can foster of the development of metacognition in students and the application of metacognition to their own instruction.

- Research on school-based methodologies for studying the complex interrelationships between and among individual, organizational, and community levels of learning and functioning that can provide solid and credible evidence to support conclusions about causal connections between variables.

Producing Credible Research: Implementation and Evaluation Considerations

Educators, researchers, and policy makers are recognizing the need for new evaluation strategies and assessment methods that are dynamic measures of learning achievement and learner development aligned with multiple types of formative and summative outcomes (Broadfoot, 2001; Gipps, 2001; McNabb, Hawkes, & Rouk, 1999; Popham, 2001; Stiggins, 2001). As people increasingly use the Internet for educational purposes, evaluation strategies and assessment methods that can fully capture the complexity, flexibility, and open-ended nature of the learning processes and outcomes in networked communities are needed. Shepard (2000) calls for recognizing that different pedagogical approaches need different outcome measures. Most of our current accountability systems are based solely on high-stakes scores pertaining to knowledge-transmission outcomes, whereas research findings on how people learn and what is needed for twenty-firstcentury citizenry pertain to achieving knowledge-adaptation and knowledge-generation, higher-order thinking, technological literacy, and social-emotional outcomes (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999; Carroll, 2001; Groff, 2001; McCombs, 2001a; McNabb, 2001; Ravitz, 2001; Repa, 2001).

Evaluation and assessment designs need to be based not only on knowledge-centered principles but also on a combination of community-centered and learner-centered principles. Some learning communities thrive, whereas others get started and dissipate. Development of new evaluation strategies and assessment methods will lead to an understanding of what makes particular communities viable and how best to support learning in both on- and off-line learning communities. Assessment measures can be designed to provide data about the balance between individualized and group learning processes, instructional strategies and activity structures, and outcomes within different types of learning communities (McCombs, 2000b).

Ahost of other issues that will expand into the twenty-first century concern the growth of technology-based learning environments. In such environments, educational psychologists can play a central role in defining research and evaluation data requirements. For example, data collected in technology-based environments may be required to calibrate the online school climate and address research-based concerns about the negative effects of the distal nature of online relationships and the amount of time these distal relationships take away from close, more nurturing relationships (McCombs, 2001a; McNabb, 2001; Repa, 2001). Research conducted by Kraut et al. (1998) indicates that a unit of measure with which to assess social ties in cyberspace is needed to foster the development of children’s overall mental, social, and physical health and well-being. Building such measures on what we have learned is essential.

Other measurement and evaluation challenges concern the balancing of content knowledge gains against other, nonacademic educational goals. Currently our educational systems have a proliferation of standards competing for the attention of teachers and students. Dede (2000) points out that no one person can possibly meet all the standards that many states are now requiring of teachers and students. This phenomenon is indicative of a knowledge transmission mode of operating. In a traditional transmission-of-knowledge learning situation, not knowing has resulted in disadvantages to some learners in terms of future learning opportunities and decisions made based on high-stakes assessment scores. In a knowledge-generation learning situation, however, not knowing provides the foundation for the inquiry and calls for assessment-centered practices for feedback and revision (Bransford et al. 1999; Carroll, 2001). The new types of assessments for which researchers and evaluators are calling rely on communities in which learners have trusting relationships; in such relationships, learners feel comfortable enough to admit that they didn’t understand a task, and they are willing and feel safe in exposing their uncertainty (Bransford, 2001; McLaughlin, 2001; Rose, 2001; Wilson, 2001).

Our present accountability system has created an overemphasis on summative assessments with little useful feedback at the personal, organizational, and community levels. Ravitz (2001) points out that current high-stakes and summative assessments are performed solely for Big Brother and do not provide feedback helpful to learners and leaders. According to Braun (2001), the present systems tend to focus on collecting summative data needed by those most removed from schools and the learning process—that is, policy makers. Little time is afforded to efforts needed to collect more formative data to serve the needs of those involved in shaping the learning process and thus its outcomes—that is teachers, students, and parents. However, issues pertaining to summative assessment need to be addressed because as a society, we want students to show some ability to transfer their learning to new situations (Bransford, 2001). There are important differences between static assessments of transfer (e.g., in which people learn something and then try to solve a new problem without access to any resources) versus dynamic assessments (e.g., assessments that allow people to consult resources and demonstrate the degree to which they have been preparing for future learning in particular areas). Portfolios properly designed can support formative data needed for learning and summative data for accountability within the community (Braun, 2001).

Formative assessment needs to combine input from all three levels of the learning community (i.e. personal, organizational, and community levels) through self-evaluation, peer critique, and expert feedback focused on conceptual understandings and skills that transfer. New evaluation strategies and assessment methods suitable for digital learning can capture learner change, growth, and improvement as it occurs in networked learning communities. This will involve issues of scale, as pointed out by Honey (2001). She suggests the real work of reform involves rethinking at the local level. She points out that we need to take seriously the challenge of working in partnership with schools and districts on terms that are meaningful to the people ultimately responsible for educating students—administrators, teachers, parents, and the students themselves (Cohen & Barnes, 1999; Meier, 1999; Sabelli & Dede, in press; Schoenfield, 1995; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). This process can perhaps best be understood as one of diagnosis—an interpretive or deductive identification of how particular local qualities work together to form the distinctive elements of the learning community. The process of adaptation through experimentation and interpretation—what Nora Sabelli calls the localization of innovation—is critical to the work of reform (Honey, 2001).

Confrey and Sabelli (2001) call for programmatic evaluations and assessment to be informed by implementation research that builds upon and contributes to increasingly more successful implementations of innovation. Implementation research expects the system to react adaptively to the intervention and documents how the intervention and the system interact, changing both the approach and the system. Confrey and Sabelli identify two scales of implementation research needed for sustainable, cumulative education improvements: within-project and across-project implementation research. Within-project implementation research implies the need to devote resources to project-level research. Across-project implementation research implies thinking hard about how to revise and refine funding efforts to ensure maximum learning from current efforts; it also implies becoming able to use this knowledge to inform the next round of programmatic research. These and other issues are areas in which educational psychology’s knowledge base will be needed.

How Can Educational Psychology’s Knowledge Base Best Be Applied to Educational Reform Issues in the Twenty-First Century?

This section builds on issues introduced in the prior sections and discusses them within a living-systems framework for education —that is, my focus here is to discuss what I believe are ways in which educational psychology’s knowledge base can be applied in whole-school or systemic reform efforts (in terms of both the overall organizational and personal domains in living systems); in reform efforts aimed at curriculum, instruction, and assessment (in terms of both the personal and technical domains of living systems); and in reform efforts aimed at creating new learning communities and cultures, including those in electronic-learning environments (in terms of both the personal and community levels of living systems). The dominance of people (the personal domain) in all levels of living systems is then discussed as the fundamental rationale for the role educational psychology can and should play in educational reform in the twenty-first century.

Implications for Application in Systemic Reform Efforts