This sample drugs research paper on drug substitution programs and offending features: 3900 words (approx. 13 pages) and a bibliography with 18 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

Overview

The prescription of opioids as a therapy for opiate dependence has a long history, and opioid substitution treatment is one of the best documented and researched therapeutic approaches in medicine. It is considered a cornerstone in the worldwide efforts to help opiate addicts and to relieve the burden for afflicted societies, mainly through a significant reduction of HIV infections in heroin injectors and the population at large and through a significant reduction of acquisitive crime by heroin users.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

However, “fighting fire with fire” has always met strong opposition. Many only accept abstinence as an outcome of treatment. The research evidence of a substantial reduction of opiate-related crime through substitution treatment can facilitate widespread political acceptance by demonstrating the benefits of this approach for the societies as well as for addicts and their families.

This research paper has two parts: the first describes the historical development of this treatment approach, and the second provides the international research evidence on the reduction in opiate-related crime associated with substitution treatment based on a systematic review of eligible studies comparing substitution treatment with diverse control groups. This research paper examines the benefits of methadone, buprenorphine, and heroin substitution maintenance.

A Short History Of Opioid Maintenance Treatment

Introduction

Maintaining opiate addicts on opiates has a long history. Opium was one of the most effective medications in ancient medicine, and its widespread use frequently led to chronic use and dependence. Medical and nonmedical rationing practice was introduced to satisfy the needs of those who were unable to discontinue its use. The discoveries of morphine and heroin and of intravenous injections were followed by even more widespread medical use and consequently concerns about chronic dependence. The idea of prescribing injectable opiates as a substitute for street heroin started in USA and was abolished on the basis of prohibitionist legislation, while it continued as regular practice in the UK. A new approach to maintaining opiate addicts on substitution therapy was initiated in the USA in 1963, with the prescription of oral methadone in the framework of a comprehensive treatment program. This approach slowly found increasing acceptance and is nowadays considered a cornerstone in the management of opiate dependence and for the prevention of HIV/AIDS in opiate injectors. The concept of heroin maintenance treatment was reactivated in order to reach out to treatment resistant heroin addicts. Based on the unanimously positive outcomes, heroin maintenance has become routine treatment for otherwise untreatable heroin addicts in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany.

The Origins: The Exceptional Power Of Opium

Prescribing and using opiates as an effective medication for a range of ailments goes back to the origins of Chinese, Sumeric, and Egyptian medicine, and probably beyond (the first traces are known from Neolithic burial sites). In Homeric times, opium in wine was offered against all evils, and in ancient Egypt, sponges soaked in opium were used during surgery. Authoritative Roman and Arabic texts have praised the uses of opium throughout the Middle Ages, and the opium-made “theriak” was used as a panacea for many centuries, in spite of prohibitive warnings by the Church. Opium tincture (laudanum) was still considered to be the most essential drug at the dawn of modern medicine by Paracelsus. It is inevitable that its addictive potential became manifest, but we do not know when and where opiate addiction was first observed and when the use of opiates as a maintenance regime started. However, opiate dependence must soon have been recognized to be difficult to overcome (Seefelder 1996).

Medical And Nonmedical Maintenance By Rationing Systems

Maintenance was the logical answer to the failure in overcoming dependence. We do know that the Roman emperor Marc Aurel was maintained on opium by the eminent physician Galenus and that the Mugal emperor Jahangir received opium maintenance from his chief physician. And far into the twentieth century, opium dispensing to registered opium addicts was practiced in some Asian countries like Pakistan, providing obviously dependent people with their daily dose. This system was abolished after the adoption of the 1961 UN Single Convention.

A comparable system of an alcohol rationing system (Bratt system) was practiced in Sweden for many years. It became unpopular as a “paternalistic” interference of state and was abolished after the Second World War.

Morphine Maintenance

Opium is rich in alkaloids with different characteristics. They were identified successively and developed further synthetically. Morphine, distilled from opium in 1804, was a revolution in pain management and found widespread use especially after the invention of syringes for injection. Once heroin (diacetylmorphine) was developed in 1874, it was again used as an effective medication for many conditions, frequently prescribed as “patent medicines.” In Europe, it was also considered to be a cure for morphine, cocaine, and opium dependence, until its own addictive potential became known. In the USA, 44 narcotic clinics were set up, most of them after the Harrison Act, which left the dependent persons without supply, and introduced tapering off morphine for detoxification purposes. By then the maintenance concept was reinvented, based on the frequency of relapses (“Tennessee system,” 1914). While the southern clinics, treating mainly iatrogenic morphine addicts, were quite successful, the New York clinics failed in maintaining young disintegrated heroin addicts (Musto 1999; Mino 1990).

Prohibition Against Maintenance

All narcotic clinics, successful or not, were closed by law in 1923, while a few doctors continued to prescribe heroin to addicts until the Single Convention of 1961, when heroin became a controlled substance and its use restricted to scientific purpose. The concept of maintaining patients on an otherwise illegal or unwelcomed consumption was incompatible with the Puritan idea of prohibition.

The one country resisting the temptation of a strict prohibition in Europe was the United Kingdom where the Rolleston Committee in 1926 recommended heroin prescribing for chronic addicts (which at the time were mainly socially integrated patients who became dependent on morphine after treatment for pain management).

The Revival Of The Maintenance Model: “Fighting Fire With Fire”

It was again in the USA where the maintenance treatment of opiate addicts was reintroduced, using methadone, a synthetic opioid, instead of morphine or diamorphine, on the basis of its advantages (oral application, longer half-life). According to the needs of the new target population – mainly socially disintegrated urban heroin injectors – a comprehensive health and social support program went along with methadone prescribing in contrast to just handing out prescriptions for unsupervised use (Dole and Nyswander 1965).

The positive effects of this new approach, especially on the health and criminal behavior of patients, confirmed by an increasing number of evaluation studies, led to a growing acceptance of the maintenance concept, in spite of “abstinence-only” arguments and opposition. But the decisive factor to speed up methadone (and buprenorphine) maintenance was the advent of the HIV epidemic. Drug injecting was recognized as a major factor for transmitting the viral infection (for hepatitis C as well). Throughout Europe, the idea of maintaining heroin addicts on opioids became increasingly acceptable, instead of restricting treatment to detoxification and abstinence-oriented approaches. The number of countries providing methadone maintenance increased from 7 in 1980 to 28 by 2005, and the number of countries providing buprenorphine maintenance rose within a few years to 21 (EMCDDA 2006). In 2008, there were ca. 670,000 patients in substitution treatment (EMCDDA 2010). The former main objective to reduce criminality and to curb the illegal heroin market was replaced gradually by a major public health concern (WHO/UNODC/ UNAIDS 2004). Finally, in 2006 the World Health Organization succeeded in putting methadone and buprenorphine on the list of essential medicines, based on evidence about the safety and effectiveness of these substances.

Opioid maintenance treatment is the predominant treatment option for opioid users in Europe. It is generally provided in outpatient settings, though in some countries it is also available in inpatient settings and is increasingly provided in prisons. Opioid maintenance is available in all EU Member States. In most countries, specialized public outpatient services are the main providers of substitution treatment. However, office-based general practitioners, often in shared care arrangements with specialized centers, play an increasing role in the provision of this type of treatment (EMCDDA 2010). The only other psychotropic substance where maintenance is practiced is tobacco, using nicotine replacement patches.

Outside of Europe, we see a different picture. By 2009, opioid maintenance treatment was available in 70 countries, but only an estimated 8 % of drug injectors received it (Mathers et al. 2010). The reasons are many-fold: most of the research evidence comes from developed countries in the West, and injecting addicts are discriminated against as morally or legally deviant; therefore only abstinence is considered to be the legitimate goal of interventions, even at the cost of infringing on human rights and medical ethics. Compulsory nonmedical reeducation camps are still frequent in some Asian countries (WHO 2009).

The Quest For Prescribing The “Original Drug”: New Research, New Practice

The increasing number of methadone patients inevitably has led to an increasing but less important number of “methadone-resistant” patients who continued to inject heroin in spite of adequate methadone dosages and care. As the systematic review of evaluations will show, methadone treatment by itself did not provide entirely satisfactory results. At the same time, the HIV epidemic made it a priority to increase coverage, i.e., to reach out to as many injectors as possible. Thus, prescribing heroin as the original and preferred substance of addicts was proposed and has been tested.

Even if the AIDS epidemic is at the origin of all initiatives to prescribe heroin in Switzerland, in the Netherlands, in Germany, in Canada, and in Spain, the idea of heroin maintenance was ready for a revival. In the UK, where the number of heroin addicts had increased and their characteristics changed, drug dependence clinics for maintenance treatment were opened in London in the 1960s, and notification of any addicts receiving a heroin prescription had to be provided to the Home Office. The much debated objectives were medical care and, at the same time, social control of addicts. For many reasons, heroin prescribing was more commonly replaced by methadone prescribing, until the AIDS epidemic led to a reconsideration and to new experimentation with injectable and smokable heroin, now in a perspective of public health interests (Strang and Gossop 1996).

Another debate started in Canada in the 1950s and again in the early 1970s, in the Netherlands and in the USA during the 1970s. The arguments were mainly focusing on heroin addiction as a chronic condition and the need to restrict its negative health and social consequences. Nonmedical options for providing heroin to addicts in the Netherlands (tolerated “home dealers” and “heroin bars”) were started but then considered to be failures (Mino 1990).

Feasibility studies on heroin prescribing were initiated in Australia. Large-scale experimental studies were finally set up in Switzerland (1994–1996), the Netherlands (1995–1997), Germany (2002–2005), Spain (2003–2004), Canada, and the UK. The Swiss cohort study provided the first positive outcomes, acknowledged by an international expert committee set up by WHO (Ali et al. 1998). As they could not separate the effects of heroin prescribing from the effects of concomitant care, the other countries set up randomized controlled trials, thereby adding essential new findings to the already established positive outcomes (see below).

A common characteristic of the new experimental studies was the aim to cover heroin addicts unable to profit from other treatments including methadone maintenance, and the provision of pharmaceutical heroin in the framework of a comprehensive assessment and treatment program. In order to avoid overdose and diversion, the intake of injectables must be made under visual supervision of staff in the clinics. In Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Germany, heroin maintenance has reached the status of a routine treatment and is paid by health insurance. Belgium decided to start another trial, and Denmark has set up heroin maintenance without further research.

Benefits And Risks Of Opioid Maintenance: A Summary Statement

A summary of findings confirms the feasibility of maintenance treatment in terms of patient satisfaction and widespread acceptance, the safety for patients and staff, the significant improvements in somatic and mental health, and a reduction in risk behavior and illicit drug use, in drug-related crime and in public nuisance offenses (Uchtenhagen 2003, WHO 2009). Maintenance therapies are increasingly integrated into treatment and care systems without negative effects for other approaches. Main risks are overdose mortality in the introductory phase of methadone maintenance and the diversion of prescribed opioids to the illegal market; they can be avoided by appropriate regimes. Economic studies have evidenced superior benefits compared to costs.

How The Treatment’s Effect On Crime Was Evaluated Across The World

Methods

Under the umbrella of the Campbell Collaboration Crime and Justice Group, a systematic review was carried out (Egli et al. 2009) in order to investigate the effect on crime of substitution programs, be it substitution by methadone or heroin, as opposed to any other type of treatment (in particular, abstinence, detoxification, psychotherapy) or no treatment at all, as well as comparative effects between different substitution therapies. All primary references used in the systematic review can be found in the Campbell Collaboration publication (Egli et al. 2009); they are identified in the current text by the first authors’ name and the year, without a space between.

A search strategy for the identification of studies was defined and followed. Relevant studies were identified through abstracts, bibliographies, and databases such as Medline, the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS), Harm Reduction Journal, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, National Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse (NHS), and National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS), as well as the bibliographies of relevant reviews. In order to be eligible, a study had to fulfill the following criteria:

– At least one of the study groups had to undergo a substitution program (using, e.g., methadone and/or opiates as substitution drugs).

– A measure of re-offending had to be given, since only such effects were included in the meta-analysis, as opposed to medical or social outcomes.

– Level 4 or higher on the Sherman scale had to be met.

The methods used, be it for review or for the analysis of the data, are as specified in Practical Meta-Analysis by Lipsey and Wilson (2001); odds ratios have been used for measuring the effects observed. An odds ratio greater than 1 stands for a reduction in the outcome measure (e.g., a positive effect with respect to the response variable). For the computation of mean effect sizes, the inverse variance method of metaanalysis (Lipsey and Wilson 2001) was used.

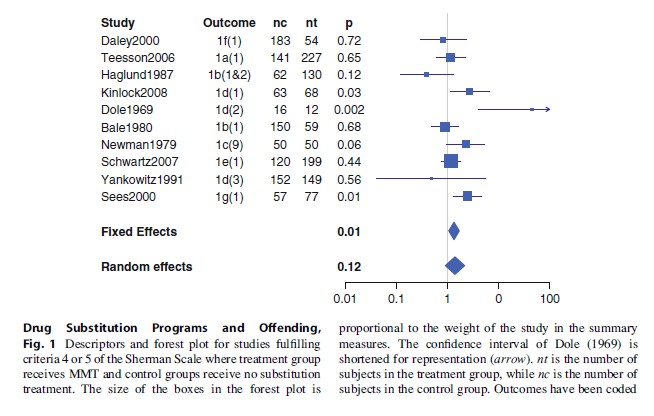

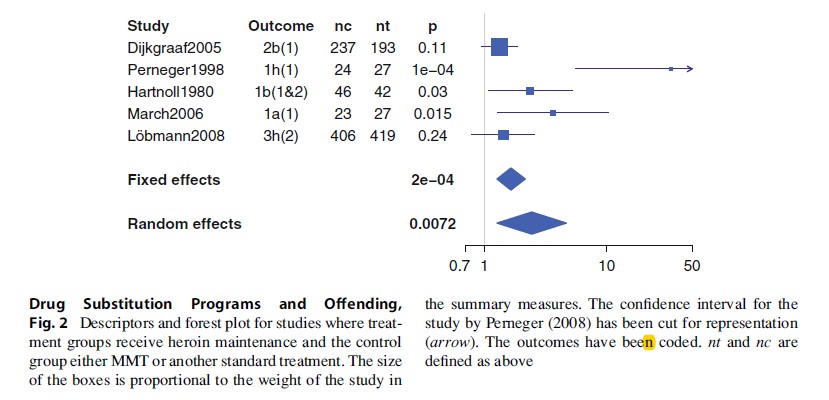

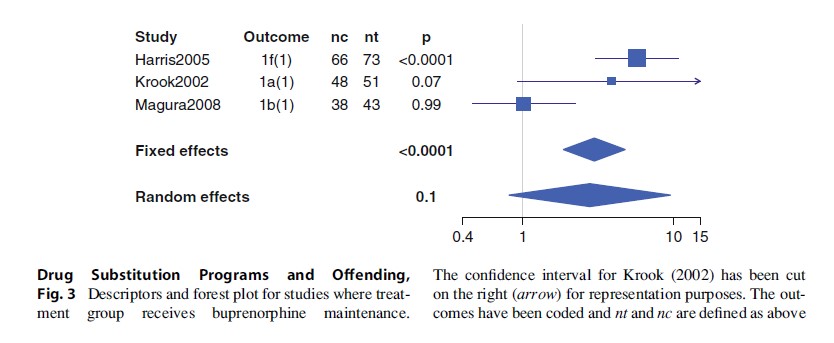

Illustrations (forest plots) have been created using R (www.r-project.org). Also, in these illustrations, the outcomes have been coded as follows: the criminal behavior (1: any offense; 2: Property crime; 3: theft) followed by the measure used (a: commission; b: arrest; c: conviction; d: incarceration; e: illegal income; f: cost of crime (estimated); g: ASI legal; h: charged) and finally the way it has been measured, in parentheses (1: self-report; 2: official sources; 3: known status; 9: unknown).

Results

Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT)

Seven RCTs (randomized controlled trials) and three high-quality quasi-experimental studies (i.e., level 4 on the Sherman Scale) were found for MMT. The control groups differed widely: three were wait-list control designs (Dole 1969; Schwartz 2007; Yancovitz 1991), one used a placebo control (Newman 1979), in one the control group received counselling (Kinlock 2008), in three others the control condition received detoxification (Daley 2000; Haglund 1978; Sees 2000), in one the control received treatment in the community (Bale 1980), and one received residential treatment (Teesson 2006). The results for these studies are shown in Fig. 1. Not surprisingly, the distribution is heterogeneous (p < 0.05), indicating meaningful variation in effect across these studies. The random effects model does not indicate a significant effect of methadone maintenance with respect to these control groups; the mean effect measure is, however, in favor of MMT. Overall effects for the four different types of control groups have also been computed; none of these show a significantly greater effect of the maintenance treatment over the treatment in the control groups. All of these effects grouped by control treatment are, however, in favor of MMT.

Effects Of Heroin Substitution Treatment

Six studies of heroin substitution programs were found, five of which were RCTs. In four of the RCTs, the control group underwent methadone maintenance (Dijkgraaf 2005; Hartnoll 1980; Lobmann 2008; March 2006), while in one (Perneger 1998), the control group underwent a conventional treatment. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

A very large effect was obtained for the study by Perneger (1998), along with a very large confidence interval. Both the small sample size and the variety of control treatments explain these two observations. Overall, for these RCTs, homogeneity is rejected (p = 0.004). If Perneger (1998) is not included in the analysis, due to the different treatment of the control group with respect to all other included studies, homogeneity is accepted (p = 0.21). The fixed effects mean effect size is then 1.55 [1.18; 2.02] (p = 0.0015). Here, a significant decrease in the criminality measures is, therefore, present for heroin over methadone maintenance treatment. However, in all of these trials except Dijkgraaf (2005), a selection effect is present that is more or less pronounced. In order to be admitted into these studies, subjects had to have followed (and failed) a program before (this selection effect is strongest for the study March (2006), where subjects were required to have had MMT at least twice before admission). Therefore, these results are overall more properly interpreted as showing a positive effect of HMT over MMT in subjects having already failed at a treatment, including MMT.

Effects Of Buprenorphine Substitution Treatment

Three randomized controlled trials concerning the effect of buprenorphine maintenance on criminal activities were found. In two of these studies, the control group was MMT (Harris 2005; Magura 2008), while in the third (Krook 2002), the control group received a placebo. The individual and overall effects are shown in Fig. 3. The homogeneity analysis rejects homogeneity (p < 0.05). The overall effect is positive, but not significant (p = 0.10). Only one of the three studies has a significant odds ratio, the study by Harris (2005), which shows the largest effect size, and is also the largest of the three studies.

When the study with a differing control group (Krook 2002) is excluded, homogeneity is still refuted (Q test p = 0.0008). Overall, there is no significant reduction in criminality when buprenorphine instead of methadone is used, although the findings suggest a slight advantage for buprenorphine relative to methadone (or placebo).

Discussion

Results show that MMT has a greater effect on criminal behavior than non-maintenance-based treatments, but not significantly so. Furthermore, the comparison between this maintenance treatment and heroin maintenance showed a significant advantage for heroin maintenance; this is true particularly for persistent users who have participated in a program before and failed. Buprenorphine maintenance also shows an advantage over alternative treatments, but one of these alternative treatments was placebo; over MMT, one study shows a significant advantage for buprenorphine, while a second study shows almost equivalent effects.

Two systematic reviews of substitution programs have been published by the Cochrane Collaboration: Ferri et al. (2006) and Mattick et al. (2009). While these reviews do not focus on crime as an outcome measure, a comparison of results with the findings from the Egli et al. (2009) review summarized above is relevant. In Mattick et al. (2009), three studies comparing methadone maintenance to no opioid replacement therapy with respect to their effect on criminal behavior are included. The results obtained are similar to the results obtained here in two respects: firstly, the effect of MMT seems to reduce criminal behavior more than the alternatives that do not include maintenance, and secondly, this effect is not significant.

In Ferri et al. (2006), four trials comparing methadone maintenance to heroin maintenance are included. One study showed a reduction in the risk of being charged when on heroin maintenance; this is in line with the results obtained here. Also, two studies considered criminal offending and social functioning in a multi-domain outcome measure, and again, heroin plus MMT yields better results than MMT alone. Again, this is in line with the results obtained here, in that heroin maintenance reduced criminality more than MMT.

Bibliography:

- Ali R, Auriacombe M, Casas M, Cottler L, Fasrrell M, Kleiber D (1998) Report of the external panel on the evaluation of the Swiss scientific studies of medically prescribed narcotics to heroin addicts. World Health Organisation, Geneva

- Dole VP, Nyswander M (1965) A medical treatment for diacetylmorphine (heroin) addiction. A clinical trial with methadone hydrochloride. J Am Med Assoc 193:80–84

- Egli N, Pina M, Skovbo Christensen P, Aebi MF, Killias M (2009) Effects of drug substitution programs on offending among drug-addicts. Campbell Syst Rev 2009:3

- EMCDDA (2006) European Monitoring Centre on Drugs and Drug Addiction EMCDDA: annual report 2006. Office for Official Publications of the European Union, Luxemburg

- EMCDDA (2010) 2010 Annual Report.http://www. emcdda.europa.eu/online/annual-report/2010

- Ferri M, Davoli M, Perucci CA (2006) Heroin maintenance treatment for chronic heroin-dependent individuals: a cochrane systematic review of effectiveness. J Subst Abuse Treat 30(1):63–72

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB (2001) Practical meta-analysis. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Ali H, Wiessing L, Hickmann M, Mattick RP et al (2010) HIV prevention, treatment and care services for people who inject drugs: a systematic review of global regional and national coverage. Lancet 375: 1014–1028

- Mattick R, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M (2009) Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence (Cochrane Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3

- Mino A (1990) Analyse scientifique de la lite´rature sur la remise controˆ le´e d’he´ro¨ıne ou de morphine (Scientific analysis of studies on the controlled prescription of heroin or morphine). Federal Office of Public Health, Bern

- Musto DF (1999) The American disease. Origins of narcotic control, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

- Seefelder M (1996) Opium. Eine Kulturgeschichte (Opium. A cultural history), 3rd edn. Ecomed, Landsberg

- Strang J, Gossop M (1996) Heroin prescribing in the British system: historical review. Eur Addict Res 2:185–193

- Uchtenhagen A (2003) Substitution management in opioid dependence. In: Fleischhacker WW, Brooks DJ (eds) Addiction. Mechanisms, phenomenology and treatment. J Neural Transmission suppl 66:33–60

- Uchtenhagen A (2008) Heroin-assisted treatment in Europe: a safe and effective approach. In: Stevens A (ed) Crossing frontiers. International developments in the treatment of drug dependence. Pavilion, Brighton, pp 53–82

- WHO (2009a) Assessment of compulsory treatment of people who use drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam. An application of selected human rights principles. World Health Organisation, Geneva

- WHO (2009b) Guidelines for the psychosocially assisted pharmacological treatment of opioid dependence. World Health Organisation, Geneva

- WHO/UNODC/UNAIDS (2004) Position paper: substitution maintenance therapy in the management of opioid dependence and HIV/Aids prevention. World Health Organisation, United Nations Office on Crime and Drugs, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/Aids