View sample communication research paper on risk communication. Browse research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

The movie, Erin Brockovich, starring Julia Roberts, told the story of a young mother with no legal training who won a court victory against Pacific Gas & Electric. Brockovich discovered that the company was illegally dumping chromium VI, a hazardous waste that caused severe illness for residents living nearby. Because of her efforts, her law firm won a class action suit against the company. The movie portrayed a case where the less powerful prevailed in court against a large company.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% OFF with 24START discount code

Because this story concerned efforts to communicate about a physical hazard, it is a story about risk communication.

The Erin Brockovich case is one sort of risk communication situation. Risk communication also involves underestimated hazards such as fire alarms that sound during a midterm exam or a tuna fish sandwich left in someone’s lunch box too long, eaten, and vomited. Risk communication concerns physical hazards of any sort, those that harm people, those that do not, those that people are worried about, and those that people are not worried about but should be. Often, risk communication is about getting people excited or calming them down (e.g., Gordon, 2003; Gordon & Rowan, 2003).

In this research paper, you will learn what risk communication is. You will also learn about the factors that affect how angry or apathetic people feel about a risk, obstacles to communicating risk, and steps for addressing these obstacles. This research paper helps you think about your reactions to risks, safety, and danger. Knowledge about risk communication is important in public relations, journalism, management, counseling, health care, and emergency response.

Risk Communication: Definition and Connection to Related Fields

Definition

Risk communication is the process of sharing meaning about any physical hazard such as dangerous work sites, environmental pollution, radiation, food-borne illness, cancer, tobacco, climate change, crime, suicide, and terrorism (Rowan, 1991, 1994; Rowan, Botan, Kreps, Samoilenko, & Farnsworth, 2009; Rowan, Kreps, Botan, Sparks, Samoilenko, & Bailey, 2008). Risk communication occurs in interpersonal communication settings, organizations, and mediated environments such as the Internet, print news, and television. Some believe that risk communication mainly concerns reputation management. If an official makes a decision that brings harm to others, reputation managers help that person re-earn the lost trust (e.g., Benoit, 2004). In this research paper, and in communication research, risk communication is a broader endeavor that explores all challenges involved in communicating about physical hazards.

To understand risk communication, it is important to learn first about two related fields, risk assessment and risk management. Risk assessment involves determining the nature, likelihood, and possibility of hazards for individuals or populations. Risk assessors work for governments, research organizations, and the private sector. Their assessments provide technical support for decisions made about hazards.

Most risk assessments involve four core questions:

- Hazard identification (Does the substance cause harm?)

- Dose-response assessment (How much x causes harm to z?)

- Exposure assessment (Do they breathe, ingest, touch it?)

- Risk characterization (A complete picture of the hazard)

- (National Research Council, 1983)

Some risk assessors analyze the effects of pesticides on animals. Others are “food safety detectives.” There are also risk assessment procedures in engineering, medicine, and occupational health and safety. Risk assessment can explain why chromiumVI, the kind Erin Brockovich investigated, is harmful. In brief, chromium VI causes cancer in humans. It is used for “chrome plating, dyes and pigments, leather tanning, and wood preserving” (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2001). Chromium (without the VI) is a naturally occurring element found in rocks, animals, plants, soil, and volcanic dust and gases.

Risk Management

Risk managers develop and implement policies that reduce the harm or likelihood of hazards. In one sense, anyone who owns or manages something that could be hazardous (a car, a home, a boat, a business) is a risk manager. In a more formal sense, those in the profession of risk management work in finance, government, corporate, and nonprofit contexts. Many with the title of risk manager are employed by financial institutions. Risk managers rely on risk assessments, regulations, policies, research, law, and ethics to safeguard the people and resources they protect (e.g., Pidgeon, Kasperson, & Slovic, 2003; Plough & Krimsky, 1987).

Social Scientific Studies of Risk

In the social sciences, there are many fields studying how people cope with risk—immediate, acute risks such as an earthquake or terrorist attack and long-term ones such as chronic disease. Scholars study hazard perception and management through the lenses of academic fields such as risk communication (e.g., Morgan, Fischhoff, Bostrom, & Atman, 2002), crisis communication (e.g., Coombs, 1999; Sellnow, Seeger, & Ulmer, 2005), persuasion (e.g., O’Keefe, 2002), health communication (e.g., BoothButterfield, 2003; Witte, Meyer, & Martell, 2001), disaster sociology (Drabek, 2001; Dynes & Rodriguez, 2005; Quarantelli & Dynes, 1985), neural sciences (e.g., Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001), decision sciences (e.g., Slovic, 2000), and behavioral economics (e.g., Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). For example, in economics, discrepancies between expert and lay perceptions of financial risk were explored as early as the 1920s. In sociology, there is extensive research on the behavior of groups during disasters (e.g., University of Delaware, Disaster Research Center, https://www.drc.udel.edu/). Scholars in several fields have explored responses surrounding the Love Canal chemical dump, the Chernobyl nuclear accident, the Alar on apples scare, and the 1984 Bhopal disaster—an accidental chemical release that killed more than 2,000 people in India. The Bhopal disaster awakened many to the realization that risks could be under- and overestimated by both experts and those affected by these risks (e.g., Plough & Krimsky, 1987; Shrivasta, 1987).

One finding from this research is that “experts” and “lay audiences” differ in their perceptions of risk and benefit. To think about this research, look at the items in List A and List B. Which ones upset you more?

List A

Smoking tobacco

Bicycle accidents

Automobile accidents

List B

Nuclear power plants

Toxic chemicals in landfills

Emissions from incinerators

Some view the items in List B as a greater source of danger and outrage than those in List A, despite the fact that data consistently show that smoking, automobiles, and even bicycles result in injury and death for humans more frequently than do nuclear power plants, toxic chemicals in landfills, and incinerator emissions As Paul Slovic, Baruch Fischhoff, and others have found, risks that are perceived as voluntary, familiar, detectable, and natural tend to be underestimated, whereas risks perceived as imposed by others, unfamiliar, difficult to detect, and man-made tend to be overestimated (e.g., Fischhoff, 1989; Fischhoff, Slovic, Lichtenstein, Read, & Combs, 1978; Sandman, 1993; Slovic, 2000).

This pattern is partly explained by the ways in which people encounter a hazard. Unlike risk assessors, who focus on a physical hazard’s physical nature and consequences (i.e., the number harmed or killed), those who manage a hazard and those affected by it care about whether the hazard is voluntary, familiar, fair, just, detectable, and “monitor-able” (e.g., Sandman, 1993). For example, people may find secondhand smoke at their workplace and Escherichia coli bacteria on their fresh vegetables more upsetting than their own smoking or the number of automobile accidents in their city. In each instance, activities such as smoking or driving are perceived as voluntary and familiar, so they are less upsetting than harms imposed by others.

This response is not entirely unreasonable: The risks one chooses are detectable and monitor-able by the person choosing them, whereas harms imposed by others are not. And yet lives can be lost because too much attention is paid to one risk and not enough to the hazard causing the greatest harm. For instance, statistics show that firearms are more likely to be associated with death due to suicide than with death in connection with crime or an accident. As Ropeik and Gray (2002) noted, “While the use of firearms in crimes receives the most media attention, the largest number of gun deaths remain suicides” (p. 89). Ropeik and Gray also wrote that those most likely to commit suicide by firearm are over age 65. Because suicide is perceived—wrongly—as a voluntary choice, and not a symptom of illness, there is less attention to this cause of death than there is to death by gunshot in the course of a crime. Risks that feel involuntary get more attention.

The CAUSE Model for Addressing Risk Communication Challenges

The CAUSE Model for Risk Communication (Rowan, 1991, 1994; Rowan et al., 2008; Rowan et al., in press) is a tool that helps communicators analyze risk communication situations, identify obstacles to effective communication, and overcome them. The model was created by noting that all risk communication situations have the components any communication situation has: message sources, channels, content, and receivers. Following Bitzer (1968), I argue that risk communication situations are distinctive because communicating about physical hazards creates predictable tensions. Specifically, when physical hazards are the topic, we expect that there may be five fundamental tensions or obstacles. Each is indexed by the letters in the word CAUSE. Because stakeholders may distrust a message source (e.g., news from a manufacturer), risk communication situations may be plagued by a lack of Confidence. Because stakeholders may not detect (hear, see) a warning, risk communication situations are beset by a lack of Awareness. Because risk communication situations are affected by confusion about what a message means (e.g., what “tornado warning” means), risk communication is challenged by a lack of Understanding. Because risk communication situations can cause disagreement among the well-informed (e.g., about whether the benefit of nuclear power is worth the risk), risk communication situations are influenced by a lack of Satisfaction with analyses of physical hazards and their management. Finally, because risk communication situations are plagued by the difficulty of encouraging people to do what they say they believe (e.g., reliably buckle their seat belts), risk communication situations are burdened by a lack of Enactment.

In addition to identifying obstacles, CAUSE directs users to research that may overcome them. That is, there is research on

| Earning | Confidence (in message sources), |

| Creating | Awareness (that a warning was sent and received), |

| Deepening | Understanding (about what the message means), |

| Gaining | Satisfaction (with analyses of problems and proposed solutions), and |

| Motivating | Enactment (moving audiences beyond agreement to action). |

Earning Confidence, the C in CAUSE

Obstacles. When we communicate about physical hazards, two fundamental obstacles involve stakeholders’ perceptions of the messenger’s motives and competence. That is, audiences may reject a message because they question the messenger’s motives or ability to make accurate statements about a hazard.

Assume that a manufacturing facility has a chemical spill. If news coverage suggests that the organization’s leaders are unresponsive to the public’s concerns, the chemical spill seems more dangerous than it would if the company were compassionate and responsive. Sandman, Miller, Johnson, and Weinstein (1993) tested this idea. Groups were given news stories with information about the same physical hazard—clean up of a perchloroethylene spill. The content of the stories was the same. One group read a news account that indicated that there was considerable distrust or controversy. In the other news account, there was little indication of such problems. Those who read the news account filled with reports of controversy thought that the hazard was more severe than those reading an account without that information.

In addition, people reject assertions if they perceive that the message sender lacks competence. In Erin Brockovich, the heroine initially struggled to be viewed as competent. She did not have a law degree, and her clothing was more provocative than professional. During the movie, however, she interviews victims of the chromium VI releases and locates records showing that Pacific Gas & Electric knew that chromium VI was dangerous and failed to clean it up. Eventually, her intelligence, thoroughness, and persistence establish her competence.

Solutions. There are other approaches to earning an audience’s trust or confidence. One is spokesperson training. Training helps managers avoid common errors such as inadvertently seeming to disrespect stakeholders’ concerns. In a televised interview, Dr. Bruce Ames of the University of California, Berkeley, explained why the amount of pesticides on most fruits and vegetables was not likely to harm health. He said, “The amount of pesticide residue—man-made pesticide residue—people are eating are actually trivial and very, very tiny amounts” (Stossel, 2007; also, see Ames, Magaw, & Gold, 1987). Ames is an expert on this topic, and his statement has merit from a risk assessment standpoint. But if one’s goal is to earn audience confidence, it fails that test. The comment seems to imply that the audience’s concerns and health are unimportant. Instead, courses in risk communication encourage communicators to earn trust by acknowledging an audience’s concerns and answering the questions of most interest to them. According to Chess (2000), audiences most want to know, “What’s the danger? What are you doing to protect me? What can I do to protect myself?” (see also, Dynes & Rodriguez, 2005).

A more comprehensive approach than viewing credibility as a matter of spokesperson training is to view this challenge as one of building credibility “infrastructure.” Heath and his associates make this argument (Heath & Abel, 1996; Heath & O’Hair, 2008; Heath & Palenchar, 2000). To earn trust, organizations need to do regular safety audits and conduct drills to ensure that everyone they affect is familiar with how to judge safety and act in an emergency. If an organization manages a physical hazard such as a manufacturing process that could harm workers or the environment, then management needs to find ways to make its processes monitor-able by others.

Enhancing an organization’s monitor-ability is the third approach to earning confidence, one advocated by Peter Sandman. Sandman (1993; see also, http://www.psandman.com/) argued that no one earns trust by asking for it. To illustrate, he told the story of an incinerator controversy in Japan. He wrote,

The big issue with incinerators is temperature. The resolution of the controversy . . . was a 7-foot neon sign on the roof of the incinerator, hooked to a temperature gauge. If a citizen wanted to know if the incinerator was burning hot enough all he or she had to do was to look out the window. (p. 36)

Other ways to enhance an organization’s monitorability are not merely to promise to be responsible but also to offer concerned groups the chance to negotiate a contract covering—for example, “What will happen in case of an accidental spill or release, how neighbors will be notified and how damages will be paid” (Sandman, 1993, p. 59).

Gaining Awareness, the A in CAUSE

According to Perry (Perry & Mushkatel, 1984), audiences may fail to receive a warning for two reasons: They may not be able to detect it or decode it. Detection involves the senses: One hears, smells, sees, and feels warnings. Decoding has to do with comprehending words or symbols in a message.

Obstacle 1: Detection. Think about a tornado approaching. How should emergency managers send a message that would reach every person on a university campus in time to protect them? Many students are focused on their studies or talking with friends. Many campuses are large. To increase the chances that everyone detects such messages, some universities have warning sirens; others send emergency messages by text messaging. Unfortunately, not all students sign up to receive emergency text messages. If a major storm or other incident would occur, only some of those on campus would receive the message. Increasingly, research is identifying ways to improve emergency preparedness on campuses (e.g., Langford, 2007), but more work is needed.

Ensuring detection of risk messages is a challenge in other contexts. Warnings are placed on foods, medicines, and household products. Scientists test these labels for effectiveness (e.g., Viscusi & O’Connor, 1987). One challenge is that consumers accustomed to safe products may not be reading warning labels.

Obstacle 2: Decoding. Decoding involves being able to read the words and symbols used in warnings. Decoding skill is essentially literacy skill, and there is research on literacy challenges in health communication (e.g., Davis, Williams, Branch, & Green, 2000). For a safety context, consider the tornado again. Suppose an emergency manager sends a text message that says a tornado watch is in effect for Hamilton County. College Student X has signed up for text messaging. Does he know that he is in Hamilton County? This is a decoding difficulty; that is, the receiver can pronounce the words Hamilton County but he may not understand that they have relevance to him. Other decoding issues occur when people try to communicate about their location to emergency personnel.Although one might assume that 9/11 operators should know how to get to each location on a campus, according to one emergency professional (J. Callan, personal communication), 9/11 operators may be better at locating street intersections and street addresses than buildings on a multibuilding campus (for research on direction giving or referential communication, see Rowan, 2003).

Solutions. Perry and Mushkatel (1984) found that rather than immediately taking the recommended protective action, when people hear a warning, they respond by talking to one another (“Did you hear that?” “Should we do something?”). While taking time to talk could be dangerous, these researchers found that people need to engage in “confirmatory behavior.” Talking to others helps people decide what the warning means, if they should respond, and how to respond. Perhaps warnings would be even more effective if message senders assumed that people will talk to share the warning. A text message such as “Tornado to hit campus. Tell people. Go to lowest floor, away from glass” may be effective. It may be that urging recipients to talk about a warning would increase its effectiveness, assuming the talk was brief.

Other steps are to increase text size and attentiongetting graphics on warning labels, learn which languages are predominant in a target area, and learn which members of a population are experiencing hearing loss. Some disabilities are easy to detect, but hearing loss may not be. Ideally, organizations might have employees fill out confidential surveys asking what the best ways are to communicate emergencies to them.

People have awareness of a word or symbol if they can detect it and recognize its referential meaning (i.e., that Hamilton County is my county; taking a pill twice a day means taking it once in the morning and once at night). In addition, though, one often needs more than awareness of a risk message. To appreciate messages about many risks, one needs deeper understanding about the meanings of key terms, the conditions under which a substance is hazardous, and so forth. Research says that there are several key obstacles to understanding complex science and technology (e.g., Rowan, 1999, 2003). Here are two challenges and ways to address them.

Deepening Understanding, the U in CAUSE

Obstacle 1: Confusing Terms. Although unfamiliar scientific terms such as nanotechnology or acrylamide seem the ones likely to confuse audiences, in fact, familiar words such as toxic, chemical, random, hormone, smoker, or even risk, terms that are easy to pronounce and spell, may be the bigger stumbling block if those communicating do not realize that they are using the term in a way that differs from their audience’s interpretation.

Steps to Clarify Confusing Terms. Communicators can clarify the meaning of a frequently misunderstood term by taking several steps. These are (a) define the word’s essential meaning, (b) say what it does not mean, (c) give several varied examples of its use so that audiences see the concept’s meaning instantiated in several contexts, and (d) discuss a false instance that audiences may think is an example but is not. I call explanations that have these components effective elucidating explanations (e.g., Rowan, 1999, 2003). For instance, people may assume that because a substance was emitted during a manufacturing process, neighbors close to the plant were exposed to it. To clarify the distinction between emission and exposure, one might say that emission means release into the environment. (Note that oxygen and carbon dioxide are emissions according to this definition. The essential parts of the term’s meaning are release and environment.) In contrast, exposure means contact.

Second, give a range of varied examples of the term, not just one example. This step is taken to ward off misconceptions about some irrelevant feature of a single example being core to a term’s meaning. To illustrate instances of exposure, one might write, “You are exposed to a substance if you eat, touch, or inhale it. Exposure is measured with blood or tissue samples; emissions are measured in pounds released.” To illustrate radiation, which is energy traveling through space, one would list radio waves, sunlight, X rays, gamma rays, not just one of these examples and not just the man-made or the natural instances. Seeing a range of examples helps audiences avoid wrongly inferring that all radiation is man-made.

Finally, it is sometimes helpful to discuss a false example and explain why it is false. In everyday use, the word random means “unpredictable” or “unimportant.” In social science, the term refers to a specific way to select and assign participants in a study. Casual uses of the word random (e.g., “That remark was totally random”) are false examples or nonexamples of a procedure where a researcher “randomly assigns participants to a condition.” In this case, the researcher is not being casual or treating the participants as unimportant. Instead, the researcher is being very careful to make sure that every member of a population such as college students has an equal chance of being either in one group, such as a group getting a new instructional method, or in another group, getting the traditional instruction. Random assignment to groups allows scientists to infer that if the treatment group’s performance on a test is significantly different from those in the control group, that difference occurred because of the treatment and not some other factor.

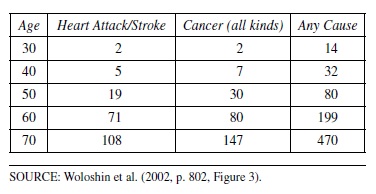

Obstacle 2: Difficulty Understanding Risk Numbers. A second problem that hampers deep understanding of physical hazards is that health and safety risks are often described numerically. Consider this statement, quoted by Woloshin, Schwartz, and Welch (2002): “This year, approximately 182,800 women in the United States will be diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, and approximately 40,800 will die from breast cancer” (p. 799).

While these numbers are large, it is hard to know what relevance they have to any particular woman. Ideally, readers want to know if they personally need to take steps to reduce their chances of contracting this disease. As these authors argue, to envision and use risk numbers, one needs to provide context and clarity.

There are several ways to do so. Woloshin and his colleagues (2002) analyzed statistical data on cancer incidence. Based on their analyses, they created easy-tointerpret risk charts for physicians’ offices. Here is a portion of one of their charts:

Risk chart for women who currently smoke*

*Someone who has smoked at least 100 cigarettes in her life and who currently smokes any amount now counts as a smoker.

Find the line with your age. The numbers next to your age tell how many of 1,000 women will die in the next 10 years from each cause of death.

Figure 1

This chart allows a patient and a physician to focus on three predictors—age, gender, and smoking status—and then consider the links between those factors and the likely causes of death.

An important point to remember in communicating risk numerically is that there is no neutral way of presenting risk (Peters, Hibbard, Slovic, & Dieckmann, 2007). Any single numerical presentation focuses attention on some aspects of a hazard but not on others. It is best to seek multiple ways of thinking about a risk to understand it.

Creating Satisfaction, the S in CAUSE

Obstacles to Securing Satisfaction (With Recommended Solutions). The fourth obstacle highlighted by the CAUSE model is lack of satisfaction with analyses of physical hazards and their management. Someone may understand the disease of depression and how medications for the disease work but disagree that these medications are a good idea for him or her. Similarly, community members may understand that a train carrying spent nuclear fuel by rail through their town poses a very low risk of exposure to ionizing radiation for inhabitants but still not agree that the train should be allowed to travel through their town.

There are many other reasons why people may be unsatisfied with risk assessments and proposals for risk management (e.g., Clark, 1984; O’Keefe, 2002). Here are two:

- Stakeholders may underestimate their personal susceptibility to harm and the severity of the potential harm (e.g., Will tanning beds cause me to get skin cancer? How susceptible are lawn care workers to hearing loss? [Smith et al., 2008; Witte et al., 2001]).

- Stakeholders may overestimate how likely, frightening, dangerous, or dreadful some event may be (e.g., riding in an airplane, living near a manufacturing facility, surviving a fire, population increases, etc.).

Solutions: Addressing Underestimation of Risk. To address disagreement because of underestimation, one tested method is to offer ways to learn more about personal vulnerability (Kreuter & Strecher, 1995). For example, the Web site https://siteman.wustl.edu/prevention/ydr/ helps patients determine their vulnerability to a dozen cancers as “average, below average, or above average.” The site also lists steps that individuals can take to minimize cancer or other disease risk (e.g., taking a multivitamin tablet daily or increasing daily servings of leafy green vegetables).

Furthermore, if a hazard is underestimated, it may be because it seems natural, voluntary, or remote—some of the risk perception factors most likely to cause a risk to be ignored. To overcome these perceptions, communicators could offer information that suggests that the hazard is actually unnatural, imposed, and likely to cause harm soon (Sandman, 1993; Slovic, 2000). Skin cancer rates are increasing (Purdue, Beane Freeman, Anderson, & Tucker, 2008). While the sun is obviously a natural phenomenon, one might doubt how “natural” it is to expose one’s skin to the sun: fashions encouraging people to wear less clothing are trends. Tanning beds are not natural, and their use is associated with melanoma, the most dangerous skin cancer (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2007). To question how voluntary smoking is, one could note that many begin smoking in late childhood or early adolescence (Krainuwat, 2005; Najem, Batuman, Smith, & Feurman, 1997). Third, future consequences may be closer than they seem: A 2008 study found melanoma incidence—the deadly skin cancer—is increasing for people aged 15–39 (Purdue et al., 2008).

Solutions: Addressing Overestimation of Risk. One source of overestimation occurs when people feel great fear toward hazards unlikely to do great harm. To manage fear, it is helpful to consider research on how frightening events are processed by the brain. Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, and Welch (2001) wrote that there are two kinds of emotions: “anticipatory emotions are immediate visceral reactions (e.g., fear, anxiety, dread)” (pp. 267–268) to hazards. In contrast, anticipated emotions are not felt-in-the-moment. Anticipated emotions are those people think they may feel at some point in the future. Anticipatory emotions cause heart racing and stomach churning. As Loewenstein and colleagues (2001) explained, anticipatory emotion

causes us to slam on the brakes instead of steering into the skid, immobilizes us when we have the greatest need for strength, causes sexual dysfunction, insomnia, ulcers, and gives us dry mouth and jitters at the very moment when there is the greatest premium on clarity and eloquence. (p. 269)

On the other hand, the absence of any fear makes it difficult to care about a hazard. The challenge for communicators is to move an audience from feeling powerless to feeling satisfied that a recommended step will work and they can personally perform that step.

Witte and her associates (e.g., Stephenson & Witte, 1998; Witte et al., 2001) have conducted studies exploring conditions in which people become convinced that a recommended step will protect them from harm and that they can perform that step. That is, people want what Witte and her associates call response efficacy and self-efficacy beliefs. Response efficacy is the belief that a recommended step will be effective. Self-efficacy is the belief that one can perform the recommended step. Using this analysis, officials who want a town to allow nuclear waste to travel through their community by rail should not simply assert that the likelihood of harm to residents is low. Instead, they should respectfully ask town inhabitants if they are interested in helping manage the hazard. Those transporting the spent fuel should share information on how to protect inhabitants in case of an accident and work with the town to create a contract covering emergency plans, drills, and conditions under which damages would be paid if an accident were to occur (Sandman, 1993; Witte et al., 2001).

Furthermore, self-efficacy is likely to develop if people (a) have taken the recommended action previously, (b) are physically capable of doing so, (c) receive messages encouraging the recommended behavior, (d) see others enacting the behavior, and (e) identify with groups where the desired behavior is encouraged (Bolam, Murphy, & Gleeson, 2004; Harwood & Sparks, 2003; Witte et al., 2001). For example, realistic training, rehearsals, and drills may be effective in helping people manage fear because they give participants a chance not only to feel anticipatory fear but also to manage this fear by, for example, grabbing an oxygen mask in a simulation of a plane losing its oxygen. At the author’s university, residence hall counselors train to keep residents safe by participating in “Fire Academy.” Instead of merely listening to lectures on fire safety, participants go to special training where they actually crawl through smoke-filled rooms, following the procedures taught to professional firefighters for staying alive in a fire. Participants find this realistic training informative and motivating (J. Callan, personal communication).

Motivating Enactment: The E in CAUSE

The final step in the CAUSE model for communicating about risk involves recognizing that satisfaction with a recommendation does not inevitably translate to enduring behavioral change. When a bare-headed cyclist suffers a head injury, his or her friends may vow to wear helmets the next time they ride, but movement from the desire to wear helmets to actually doing so is not a certainty. Behavior change research shows that there are two predictable obstacles: difficulties in initiating change and in sustaining the new behavior (e.g., Booth-Butterfield, 2003; Clark, 1984; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984; Prochaska, Norcross, & DiClemente, 1995).

Obstacle 1: Resistance to Initiating Behavior Change. Even when people agree that change is warranted, they struggle because change is stressful (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984; Prochaska et al., 1995). As Prochaska and associates explained, change involves inevitable losses, such as enjoyed prior habits. According to BoothButterfield (2003), one should consider whether the behavior one wishes to change is relatively “embedded” or “unembedded.” Embedded behaviors are frequent and integral to daily routine. For some, watching television daily and buckling seat belts are routines. In contrast, unembedded behaviors occur infrequently. Occasional trips to a city or cleaning the attic are examples of these kinds of behaviors.

Obstacle 2: Maintaining Behavior Change. Maintaining behavior change involves turning unembedded behavior into an embedded one. Unfortunately, shortly after a new risk reduction behavior is adopted, it can be easily extinguished (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984).

Solutions to Encourage Behavior Change. BoothButterfield (2003) recommends that prior to making a change, one should consider how often a new behavior should occur, with whom, and in what setting, and how participants will react and feel. When a precise, reliable time for the behavior is identified, others who will be performing the behavior are found, the right setting is located, and inducements to encourage the right feelings are offered, then the new behavior is more likely to occur. Clark (1984) argued that behavior is most likely to change when initial steps are made easy, simple, and rewarding. Prochaska, Levesque, Prochaska, Dewart, and Wing (2001) recommended that a change initiator minimize the negatives by noting that the negatives are usually temporary. Someone new to exercising might tell himself or herself that the time it will take to exercise daily will be offset by reduced risk of injury and a sense of well-being.

Sustaining a new behavior is the next challenge. Airline passengers who fly frequently feel that they know all the safety instructions, so forcing themselves to attend to safety placards on each flight is difficult. Prochaska and colleagues (2001) suggested creating new goals to sustain behavior change. Perhaps a frequent flier could remind himself or herself that between 1983 and 2000, more than half of all passengers involved in serious aircraft accidents survived (Ripley, 2008, p. 45). According to Ripley, those who survive reported having read and remembered safety instructions. In a health context, good behaviors can be sustained with encouragement and reminders from physicians, such as appointment reminders (Lantz, Stencil, Lippert, Beversdorf, & Jaros, 1995).

While reminder cards and rehearsing may seem small matters, there is evidence this is not the case. Ripley (2008) told the story of Rick Rescorla, the head of security for Morgan Stanley Dean Witter at the World Trade Center. Rescorla was a Vietnam veteran who started “running the entire company through his own frequent, surprise fire drills” (p. 44). The company, an investment banking firm, had employees who could literally make millions of dollars in the time a fire drill might take. Regardless, Rescorla had them drill. He would time them and encourage them to move quickly by yelling through a bullhorn. On September 11, 2001,

Rescorla heard an explosion and saw Tower I burning from his office window. . . . (He) grabbed his bullhorn, walkietalkie and cell phone and began systematically ordering Morgan Stanley employees to get out. . . . When the [second] tower collapsed, only 13 Morgan Stanley colleagues— including Rescorla and four of his security officers—were inside. The other 2,687 were safe. (p. 45)

Rescorla and the security guards perished that day. His steadfast commitment to rehearsing evacuation, even with top executives, saved their lives.

Conclusion

This research paper defined risk communication as the process of sharing meaning about physical hazards, described the related fields of risk assessment and risk management, and presented the CAUSE model for effective risk communication. Risk communication is one of the most interesting and important areas of communication research.

The world is not going to run short of physical hazards or difficulties communicating about them. Readers of this research paper should feel encouraged to learn more about risk communication research and to contribute to this field themselves. The more savvy risk communication researchers there are, the safer we all will be.

Bibliography:

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2001, February). ToxFAQs for chromium. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tf.asp?id=61&tid=17

- Ames, B. N., Magaw, R., & Gold, L. S. (1987). Ranking possible carcinogens. Science, 236, 271–280.

- Benoit, W. L. (2004). Image restoration discourse and crisis communication. In D. P. Millar & R. L. Heath (Eds.), Responding to crisis: A rhetorical approach to crisis communication (pp. 263–280). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bitzer, L. (1968). The rhetorical situation. Philosophy and Rhetoric, 1, 1–14.

- Bolam, B., Murphy, S., & Gleeson, K. (2004). Individualization and inequalities in health: A qualitative study of class identity and health. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 1355–1365.

- Booth-Butterfield, M. (2003). Embedded health behaviors from adolescence to adulthood: The impact of tobacco. Health Communication, 15, 171–184.

- Chess, C. (2000, May). Risk communication. Presentation for the Risk Communication Superworkshop, sponsored by the Agricultural Communicators in Education and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Orlando, FL.

- Clark, R. A. (1984). Persuasive messages. New York: Harper & Row.

- Coombs, W. T. (1999). Ongoing crisis communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Davis, T. C., Williams, M. V., Branch, W. T., & Green, K. W. (2000). Explaining illness to patients with limited literacy. In B. B. Whaley (Ed.), Explaining illness: Research, theory, and strategies (pp. 123–146). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Drabek, T. (2001). Disaster warning and evacuation responses by private business employees. Disasters, 25, 76–94.

- Dynes, R. R., & Rodriguez, H. (2005). Finding and framing Katrina: The social construction of disaster. In Understanding Katrina: Perspectives from the social sciences. New York: Social Science Research Council. Available at: https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/finding-and-framing-katrina-the-social-construction-of-disaster/

- Fischhoff, B. (1989). Risk: A guide to controversy. In National Research Council (Ed.), Improving risk communication (pp. 211–319). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S., Read, S., & Combs, B. (1978). How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes toward technological risks and benefits. Policy Sciences, 9, 127–152.

- Gordon, J. (2003). Risk communication and foodborne illness: Message sponsorship and attention to stimulating perception of risk. Risk Analysis, 23, 1287–1296.

- Gordon, J., & Rowan, K. E. (2003, November). A short course in risk communication. Presentation for the annual meeting of the National Communication Association, Miami, FL.

- Harwood, J., & Sparks, L. (2003). Social identity and health: An intergroup communication approach to cancer. Health Communication, 15, 145–170.

- Heath, R. L., & Abel, D. D. (1996). Proactive response to citizen risk concerns: Increasing citizens’ knowledge of emergency response practices. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8, 151–171.

- Heath, R. L., & O’Hair, H. D. (2008). Terrorism: From the eyes of the beholder. In H. D. O’Hair, R. L. Heath, K. J. Ayotte, & G. R. Ledlow (Eds.), Terrorism: Communication and rhetorical perspectives (pp. 17–42). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Heath, R. L., & Palenchar, M. (2000). Community relations and risk communication: A longitudinal study of the impact of emergency response messages. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12, 131–161.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. (2007). The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: A systematic review. International Journal of Cancer, 93, 678–683.

- Krainuwat, K. (2005). Smoking initiation prevention among youths: Implications for community health nursing practice. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 22, 195–204.

- Kreuter, M. W., & Strecher, V. J. (1995). Changing inaccurate perceptions of health risk: Results from a randomized trial. Health Psychology, 14, 56–63.

- Langford, L. (2007). Preventing violence and promoting safety in higher education settings: Overview of a comprehensive approach. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED537696

- Lantz, P. M., Stencil, D., Lippert, M. T., Beversdorf, S., & Jaros, L. (1995). Breast and cervical cancer screening in a lowincome managed care sample: The efficacy of physician letters and phone calls. American Journal of Public Health, 85, 834–836.

- Loewenstein, G. F., Weber, E. U., Hsee, C. K., & Welch, N. (2001). Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 267–386.

- Morgan, M. G., Fischhoff, B., Bostrom, A., & Atman, C. J. (2002). Risk communication: A mental models approach. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Najem, G. R., Batuman, F., Smith,A. M., & Feurman, M. (1997). Patterns of smoking among inner-city teenagers: Smoking has a pediatric onset. Journal of Adolescent Health, 20, 226–231.

- National Research Council. (1983). Risk assessment in the federal government: Managing the process. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- O’Keefe, D. J. (2002). Persuasion: Theory and research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Perry, R. W., & Mushkatel, A. H. (1984). Disaster management: Warning response and community relocation. Westport, CT: Quorum.

- Peters, E., Hibbard, J., Slovic, P., & Dieckmann, N. (2007). Numeracy skill and the communication, comprehension, and use of risk-benefit information. Health Affairs, 26, 741–748.

- Pidgeon, N., Kasperson, R. E., & Slovic, P. (2003). The social amplification of risk. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Plough, A., & Krimsky, S. (1987). The emergence of risk communication studies: Social and political context. Science, Technology, and Human Values, 12, 4–10.

- Prochaska, J. M., Levesque, D. A., Prochaska, J. O., Dewart, S. R., & Wing, G. R. (2001). Mastering change: A core competency for employees. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 1, 7–15.

- Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1984). The transtheoretical approach: Crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones Irwin.

- Prochaska, J. O., Norcross, J. C., & DiClemente, C. C. (1995). Changing for good. New York: Avon.

- Purdue, M. P., Beane Freeman, L. E., Anderson, W. F., & Tucker, M. A. (2008). Recent trends in the incidence of cutaneous melanoma among U.S. Caucasian young adults. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 159, 1–4. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2741632/

- Quarantelli, E. L., & Dynes, R. R. (1985). Community response to disasters. In B. Sowder (Ed.), Disasters and mental health: Selected contemporary perspectives (pp. 158–168). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Ripley, A. (2008, June 9). How to survive a disaster. Time, 40–45.

- Ropeik, D., & Gray, G. (2002). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Rowan, K. E. (1991). Goals, obstacles, and strategies in risk communication:A problem-solving approach to improving communication about risks. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 19, 300–329.

- Rowan, K. E. (1994). Why rules for risk communication fail: A problem-solving approach to risk communication. Risk Analysis, 14, 365–374.

- Rowan, K. E. (1999). Effective explanation of uncertain and complex science. In S. Friedman, S. Dunwoody, & C. L. Rogers (Eds.), Communicating new and uncertain science (pp. 201–223). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Rowan, K. E. (2003). Informing and explaining skills: Theory and research on informative communication. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), The handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 403–438). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Rowan, K. E., Botan, C. H., Kreps, G. L., Samoilenko, S., & Farnsworth, K. (2009). Risk communication education for local emergency managers: Using the CAUSE Model for research, education, and outreach. In R. L. Heath & H. D. O’Hair (Eds.), Handbook of crisis and risk communication (pp. 168–191). New York: Routledge.

- Rowan, K. E., Kreps, G. L., Botan, C. H., Sparks, L.,

- Samoilenko, S., & Bailey, C. (2008). Responding to terrorism: Risk communication, crisis communication, and the CAUSE Model. In D. O’Hair, R. L. Heath, K. J. Ayotte, & G. R. Ledlow (Eds.), Terrorism: Communication and rhetorical perspectives (pp. 425–453). Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

- Sandman, P. M. (1993). Responding to community outrage: Strategies for effective risk communication. Fairfax, VA: AIH Association.

- Sandman, P. M., Miller, P. M., Johnson, B. B., & Weinstein, N. D. (1993).Agency communication, community outrage, and perception of risk: Three simulation experiments. Risk Analysis, 13, 585–598.

- Sellnow, T. L., Seeger, M. W., & Ulmer, R. R. (2005). Constructing the “new normal” through post-crisis discourse. In H. D. O’Hair, R. L. Heath, & G. R. Ledlow (Eds.), Community preparedness and response to terrorism (pp. 167–189). Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Shrivasta, P. (1987). Bhopal: Anatomy of crisis. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

- Slovic, P. (2000). The perception of risk. Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

- Smith, S. W., Rosenman, K., Kotowski, M., Glazer, E., McFeters, C., Law, A., et al. (2008). Using the EPPM to create and evaluate the effectiveness of brochures to increase the use of hearing protection in farm and lawn care workers. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 36, 200–218.

- Stephenson, M. T., & Witte, K. (1998). Fear, threat, and perceptions of efficacy from frightening skin cancer messages. Public Health Reviews, 26, 147–174.

- Stossel, J. (2007, November 16). Myths, lies, and downright stupidity. ABC News. Retrieved August 4, 2008, from http://abcnews.go.com/2020/Stossel/Story?id=1898820& page=1

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decision and the psychology of choice. Science, 211, 453–458.

- Viscusi, W. K., & O’Connor, C. (1987). Hazard warnings for workplacerisks:Effectsonriskperceptions,wagerates,andturnover. In W. K. Viscusi & W. A. Magat (Eds.), Learning about risk: Consumer and worker responses to hazard information (pp. 98–124). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Witte, K., Meyer, G., & Martell, D. (2001). Effective health risk messages: A step-by- step guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Woloshin, S., Schwartz, L. M., & Welch, H. G. (2002, June 5). Risk charts: Putting cancer in context. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 94, 799–804.